Abstract

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) is a major of cause of diarrhea among children in developing countries. Although EPEC is a human specific pathogen, some related strains are natural pathogens of animals, including laboratory-bred rabbits. We have identified two chromosomal loci in rabbit-specific EPEC (REPEC) O15:H− strain 83/39, which are predicted to encode long polar fimbriae (LPF). lpfR154 was identical to a fimbrial gene cluster, lpfO113, identified previously in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) O113:H21. The second locus, lpfR141, comprised a novel sequence with five predicted open reading frames, lpfA to lpfE, that encoded long fine fimbriae in nonfimbriated E. coli ORN103. The predicted products of lpfR141 shared identity with components of the lpfABCC′DE gene cluster from EHEC O157:H7, and the fimbriae were similar in morphology and length to LPF from EHEC O157:H7. Interruption of lpfR141 resulted in significant attenuation of REPEC 83/39 for rabbits with respect to the early stages of colonization and severity of diarrhea. However, there was no significant difference in the number of bacteria shed at later time points or in overall body weight and mortality rate of rabbits infected with lpfR141 mutant strains or wild-type REPEC 83/39. Although rabbits infected with the lpfR141 mutants did not develop severe diarrhea, there was evidence of attaching and effacing histopathology, which was indistinguishable in morphology, location, and extent compared to rabbits infected with wild-type REPEC 83/39. The results suggested that lpfR141 contributes to the early stages of REPEC-mediated disease and that this is important for the development of severe diarrhea in susceptible animals.

Human strains of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) are an important cause of infant diarrhea in developing countries (19, 24). EPEC is principally a pathogen of the small bowel and one of several gastrointestinal pathogens of humans and animals able to induce distinctive lesions in the gut, termed attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions (reviewed in reference 10). These lesions are characterized by localized destruction of intestinal microvilli, intimate attachment of the bacteria to the host cell surface, and the rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins underneath tightly adherent bacteria. A/E lesion formation is mediated by the products of a large pathogenicity island called the locus for enterocyte effacement (LEE) (17). The LEE of EPEC contains 41 open reading frames (ORFs) organized into several polycistronic operons (9). Approximately half of the genes in LEE code for a type III secretion system that directs the secretion of several LEE-encoded proteins, known as EPEC secreted proteins or Esps. These include EspA, -D, -B, -F, -G, and -H, Tir/EspE, and Map (9, 14, 31), of which EspA, -B, and -D and Tir play a direct role in A/E lesion formation (10). Other A/E pathogens include the closely related human pathogen, enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), and the animal pathogens, rabbit-specific enteropathogenic E. coli (REPEC) and Citrobacter rodentium (18, 25, 27, 35). Rabbits infected with REPEC show the same clinicopathological features as humans infected with EPEC and as such provide an invaluable small animal model of EPEC infections (25).

In addition to LEE, many A/E pathogens produce fimbriae that are essential for colonization of the host. Human strains of EPEC produce a type IV bundle-forming pilus, BFP that is essential for full virulence and is required for bacterial microcolony formation on the host cell surface (7). BFP may also act as an initial adhesin in vivo (5). Strains of REPEC also express fimbriae that are essential for colonization. These include AF/R1 (adherence factor/rabbit 1) encoded by an 86-MDa plasmid of REPEC O15:H− strain RDEC-1; AF/R2, which is produced by REPEC O103:H2; and Ral of REPEC O15:H− strain 83/39 that is also plasmid encoded (1, 23, 34). All of these fimbriae enhance the virulence of their corresponding strains.

The recently determined genome sequence of EHEC O157:H7 EDL933 has revealed several fimbrial gene clusters, including two encoded by O-islands 141 and 154. These are predicted to encode homologs of long polar fimbriae (LPF) (11, 22), and are located adjacent to yhjW and pstS, respectively. LPF were first described in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and have been shown to direct the attachment of serovar Typhimurium to murine Peyer's patches in vivo (3, 4). Their expression is controlled by phase variation, which provides a means of evading cross immunity among different Salmonella serotypes (21). O-island 141 of EHEC O157:H7 encodes fimbriae that are similar in structure and length to LPF from serovar Typhimurium but do not show a polar distribution (30). The lpfABCC′DE gene cluster is unique to EHEC O157:H7 and EPEC O55:H7 and is able to mediate microcolony formation by EHEC O157:H7 and adherence of nonfimbriated E. coli ORN172 to epithelial cells (30). Recently, we identified a novel lpf gene cluster in EHEC O113:H21 that enhanced bacterial adherence to Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) epithelial cells (8). This locus has the same chromosomal location as O-island 154 in EHEC O157:H7 and was termed lpfO113. It is also found in several serotypes of EPEC and EHEC, including O111:H− and O26:H11.

We describe here the identification of two lpf gene clusters in REPEC strain 83/39 that occupy the same chromosomal location in REPEC as O-islands 141 and 154 in EHEC O157:H7. lpfR154 was identical in nucleotide sequence to the gene cluster, lpfO113 from EHEC O113:H21, whereas lpfR141 was a novel locus that encoded long fine fimbriae similar to the LPF from EHEC O157:H7. In addition, lpfR141 appeared to play a role in the early stages of REPEC infection of rabbits and was essential for the development of severe diarrhea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Wild-type strains of pathogenic E. coli, were obtained from our culture collection (20). Unless otherwise indicated, E. coli cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or LB agar plates and then incubated aerobically at 37°C overnight. Electrocompetent cells were prepared by growing bacteria at 30°C. Where appropriate, antibiotics were added to growth media to the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 100 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml. For the induction of λ Red Recombinase from plasmid pKD46, 100 mM arabinose was added to LB broth (6).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| REPEC 83/39 | Wild-type REPEC O15:H− (Rifr) | 1 |

| REPEClpfR141 | REPEC 83/39 carrying an insertional mutation disrupting lpfBR141 (Rifr Cmr) | This study |

| REPEClpfR154 | REPEC 83/39 carrying an insertional mutation disrupting lpfCR154 (Rifr Kanr) | This study |

| REPEClpfR141/154 | REPEC 83/39 carrying insertional mutations disrupting lpfBR141 and lpfCR154 (Rifr Kanr Cmr) | This study |

| ORN103 | thr-1 leu-6 thi-1 Δ(argF-lac)U169 xyl- and ara-13 mtl-2 gal6 rpsL tonA2 fhuA2 minA monB recA13 Δ(fimABCDEFGH) | 29 |

| XL-1 Blue | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA46 thi relA1 lac-F′ [proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10] (Tetr) | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-Script | High-copy cloning vector (Ampr) | Stratagene |

| pCR:lpfR141 | pCR-Script carrying lpfABCDER141 | This study |

| pCR:lpfR154 | pCR-Script carrying lpfABCDR541 | 8 |

| pKD46 | Expression vector for phage λ red recombinase (γ, β, exo) induced by l-arabinose, thermosensitive (Ampr) | 6 |

Rifr, rifampin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Kanr, Kanamycin resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance.

DNA manipulations.

Standard techniques were used for all recombinant DNA manipulations, Southern and dot blotting, and electrophoresis procedures (26). DNA-modifying enzymes (Promega, Madison, Wis.) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Chromosomal DNA was isolated by using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and plasmid DNA was isolated by using the Qiaprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen).

PCR procedures and cloning of lpfR141 and lpfR154.

PCR amplification was performed on 500 ng of template DNA with ca. 1 μg of each primer per 100-μl reaction. PCR primers used in the present study are listed in Table 2. Amplification of components of the lpf gene cluster was performed under the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 50 s at the appropriate annealing temperature (Table 2) and 1 min at 72°C. This was followed by an extension time of 5 min at 72°C. Where required DIG-dUTP was incorporated into the PCR according the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). O-islands lpfR141 and lpfR154 from REPEC 83/39 were amplified from genomic DNA by using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche) and the primer pairs O-141F/O-141R and O-154F/O-154R (8). The final 6.0- and 5.5-kb products were purified by using the Concert Nucleic Acid Purification System (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.) and cloned into pCR-Script for determination of DNA sequence.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer | Sequence | Annealing temp (°C) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lpfDR141 | LPFDF | 5′-GAACTGTAGATGGGTAC-3′ | 48 | This study |

| LPFDR | 5′-AGCAGGCATAACGCAAG-3′ | |||

| lpfAR141 | LPFAF | 5′-GAAAAAGGTTCTGTTTG-3′ | 42 | This study |

| LPFAR | 5′-GTTGTAAGTCAGGTTGA-3′ | |||

| lpfA-BR141 | LPFAF | 5′-GAAAAAGGTTCTGTTTG-3′ | 42 | This study |

| LPFBR | 5′-TCAGTTAATCGGCTTCGTC-3′ | |||

| lpfCR141 | LPFCF | 5′-TTGTAGCCCAACAGACG-3′ | 42 | This study |

| LPFCR | 5′-CAGGGTATCGATCAACAC-3′ | |||

| lpfER141 | LPFEF | 5′-CCATACATGGTCGAACTG-3′ | 42 | This study |

| LPFER | 5′-GTACAGTAAAGTCGACC-3′ | |||

| eaeβ | EaeβF | 5′-GCGCGTTACATTGACTC-3′ | 42 | 2 |

| EaeβR | 5′-GGGCAAAAAACTCAACG-3′ | |||

| ral | RalF | 5′-GTCGCAGTAACGGCTGC-3′ | 48 | 1 |

| RalR | 5′-GCTTAAACGAAGGCCCG-3′ |

Nucleotide sequencing and analysis.

Plasmid DNA was prepared for sequence analysis by using a PRISM Ready Reaction Dye Deoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The nucleotide sequence of samples was determined by automated DNA sequencing by using an Applied Biosystems model 373A DNA sequencing system. DNA sequences were assembled by using Sequencher 3.1.1 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.). GeneMark.hmm for prokaryotes was used to identify putative genes and BLAST programs were used to determine nucleotide and amino acid homology with sequences in GenBank.

Construction of lpf mutants of REPEC O15:H− (83/39).

Insertional mutations were created in lpfR141 and lpfR154 by using the λ Red Recombinase method, which promotes homologous recombination of linear DNA into the bacterial host chromosome (6). To construct a lpfR141 mutant, a chloramphenicol resistance gene from pACYC184 was ligated into a XhoI site of lpfBR141. In a similar manner, a kanamycin resistance gene was ligated into a PstI site of lpfCR154. After amplification of the inactivated genes, PCR products were then treated with DpnI to remove template DNA. The thermosensitive plasmid, pKD46, was introduced into REPEC 83/39, and electrocompetent cells expressing Red Recombinase were prepared. Approximately 50 ng of lpfBR141:cm or lpfCR154:km PCR product was then electroporated into REPEC 83/39(pKD46). Chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistant clones were assessed for correct incorporation of the resistance marker into target lpf genes by PCR. In order to create a double-mutant strain, the lpfCR154:km REPEC 83/39 mutant containing pKD46 was electroporated with lpfBR141:cm PCR product. The single mutants were designated REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR154, and the double mutant was designated REPEClpfR141/R154.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR technique.

Bacterial strains were grown to exponential phase and whole-cell RNA was extracted by using Trizol reagent (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was treated with DNase and then purified by using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), including a second DNase treatment according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was generated from the eluted RNA by reverse transcription (RT) by using random hexamers and Superscript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR of cDNA and a no RT control was performed with Taq DNA polymerase as described above.

Quantitative adherence and FAS test.

For quantitative assessment of adherence, adherence assays were performed with CHO-K1 cells as described previously (8, 32). The results were expressed as the percentage of recovered bacteria compared to the original inoculum and were the mean of duplicate wells from five independent experiments. For fluorescent actin staining (FAS) assays, CHO-K1 cells were cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates on 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips, infected with bacterial strains and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-phalloidin (Sigma) as described previously (15).

Infection of rabbits.

For in vivo assays of virulence, 4- to 5-week-old New Zealand White rabbits were infected with 4 × 106 CFU of test strains, including wild-type REPEC 83/39, the single mutant REPEClpfR141, and the double mutant REPEClpfR141/R154. The inoculum was prepared from strains grown stationary overnight in Penassay broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline as described previously (1, 16). Thirty minutes before inoculation, animals were treated with sodium bicarbonate and divided into groups of 5. Rabbits were examined daily for 20 days and monitored for body weight and evidence of diarrhea. Diarrhea severity was assessed on a scale of 0 to 4, where very mild diarrhea was assigned a value of 1 and severe diarrhea was scored as 4. We defined very mild diarrhea as some signs of loose stools on the rectal swab and possible staining of the fur around the anus and severe diarrhea as extensive soiling of the rear and hind limbs, fluid on the rectal swab, and the presence of diarrheic feces in the cage. Each day after infection, cotton swabs were used to sample contents from the distal 3 cm of the rectum. The material collected in this manner was emulsified in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, and serial dilutions were plated onto MacConkey agar with appropriate antibiotic selection. Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that the number of bacteria obtained in this way corresponds closely to the number of bacteria obtained from the colon and rectum at necropsy.

Biopsies for examination by light and electron microscopy were taken from the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, and colon from animals that were killed because they were moribund and from those killed at the end of the observation period.

Electron microscopy and histology.

To visualize fimbriae encoded by lpfR141, pCR-Script carrying lpfR141 was transformed into a nonfimbriated E. coli strain, ORN103 (8, 29). Transformants were grown stationary in LB broth at 37°C overnight, and the bacteria were allowed to adhere to a 300-mesh copper grid (Alltech, Deerfield, Ill.). Fimbriae were visualized by negative staining with 1.0% ammonium molybdate, and grids were analyzed by using a Phillips CM12 electron microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, Oreg.) at an accelerated voltage of 60 kV.

Biopsies taken from experimentally infected animals were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by postfixation in 2.5% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. After dehydration in a graded acetone series, the tissue was embedded in Epon-Araldite epoxy resin. Thin (0.5 μm) sections were stained with 10% uranyl acetate and 2.5% lead citrate before they were viewed under a Phillips CM12 electron microscope at 60 kV. For light microscopic analysis, intestinal sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution before being dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in paraffin. Thick sections (4 μm) were cut and stained with 1% methylene blue.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of results was performed by using InStat version 3.0 and Prism version 3.0 (GraphPad InStat Software, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). A P value of <0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence presented in the present study has been assigned GenBank accession no. AY156523.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of lpfR141 from REPEC 83/39.

Sequencing of the lpfR154 gene cluster from REPEC 83/39 revealed that this O-island was identical to the lpfO113 locus characterized previously in EHEC O113:H21 (accession no. AY057066) (8). Further O-island amplification of REPEC 83/39 uncovered a second novel lpf gene cluster (lpfR141) in the same location as O-island 141 of EHEC O157:H7. Nucleotide sequencing of lpfR141 revealed five predicted ORFs, lpfA-E, spanning 5,919 bp. The distance between each ORF ranged from 83 bp (between lpfA and lpfB) to 5 bp (between lpfDR141 and lpfER141), suggesting that these genes comprise an operon. Overall, the nucleotide sequence of lpfR141 had a G+C content of 46.2%, which is lower than that of the E. coli K-12 genome (50.8%).

The predicted amino acid sequences of lpfR141-encoded components shared significant similarity with proteins involved in fimbrial biogenesis, in particular the LPF proteins (Table 3). Based on the predicted and known functions of the proteins encoded by other lpf and type I fimbrial operons, the predicted function of each protein is listed in Table 3. As expected, the putative chaperone (LpfBR141) and outer membrane usher (LpfCR141) were highly conserved among the different gene clusters, whereas the putative structural components, LpfAR141, LpfDR141, and LpfER141, were more variable (Table 3). Overall, the predicted components of lpfR141 were most related by amino acid identity to the lpf products of serovar Typhimurium and lpfABCC′DE products of EHEC O157:H7.

TABLE 3.

Extent of amino acid sequence identity and similarity of components lpfR141 from REPEC 83/39 with their closest homologuesa

| Protein | Putative functionb | No. of amino acids | % Amino acid identity (% similarity) to homologs from:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O157:H7 O-141 | Serovar Typhimurium lpf | E. coli K-12 fim | |||

| LpfA | Major fimbrial subunit | 174 | 64 (74) | 65 (77) | 35 (50) |

| LpfB | Chaperone | 228 | 65 (78) | 69 (78) | 38 (59) |

| LpfC | Usher | 843 | 67 (78) to LpfCc | 72 (83) | 42 (60) |

| 69 (84) to LpfC′ | |||||

| LpfD | Minor fimbrial component | 351 | 39 (56) | 45 (59) | 26 (40) |

| LpfE | Adhesin | 174 | 47 (67) | 52 (73) | 29 (41) |

The GenBank accession numbers for EHEC O157:H7 lpfABCC′DE, serovar Typhimurium lpf, and the fim operon of E. coli K-12 are AE005581, AE008868, and AE000502 respectively.

Properties and predicted function of putative gene products are based on their homology to related gene products.

The EHEC O157:H7 lpfABCC′DE gene cluster encodes two ORFs with significant homology to LpfC from serovar Typhimurium. One shows homology to the 5′ end of LpfC, and the other, denoted LpfC′, is homologous to the 3′ end of LpfC.

Distribution of lpfR141 among E. coli pathogens.

To determine the distribution of the novel lpfR141 gene cluster among pathogenic E. coli, we used PCR and dot blot hybridization to screen strains of diarrheagenic E. coli for the presence of lpfR141 by using sequences specific for lpfDR141. lpfDR141 was found in several isolates of LEE-positive and LEE-negative EHEC, as well as several serotypes of EPEC (Table 4). Overall, lpfDR141 was present in all of 10 REPEC strains, none of 3 eae-negative animal E. coli isolates, 11 of 18 EPEC isolates, 6 of 10 LEE-positive EHEC strains, 4 of 12 LEE-negative EHEC strains (Table 4), 1 of 5 enteroaggregative E. coli, and 1 of 5 enterotoxigenic E. coli strains tested (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Distribution of lpfDR141 among different strains of REPEC, EPEC, and EHEC

| Strain | Serogroup | Origin | Presence (+) or absence (−) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eaea | lpfDR141 | |||

| REPEC 83/39 | O15:H− | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC RDEC-1 | O15:H− | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 83/146 | O153:H7 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 84/110/1 | O103:H2 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC B10 | O103:H2 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 82/260 | O20:H7 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 82/123 | O109:H2 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 82/90 | O132:Z | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 82/183 | O128:Z | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| REPEC 82/215/2 | O8 | Rabbit diarrhea | + | + |

| E. coli 83/64 | R:H26 | Rabbit diarrhea | − | − |

| E. coli 84/177 | O2:H6 | Rabbit diarrhea | − | − |

| E. coli 6708-87 | O103:H2 | Goat diarrhea | − | − |

| EPEC E2348/69 | O127:H6 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC O55 | O55:H7 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC E851/71 | O142:H6 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC C771 | O142:H6 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC 12-1 | O119 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC E990 | O86:H− | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC E464 | O125:H19 | Human diarrhea | + | − |

| EPEC 11-1 | O111:H− | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC Stoke W | O111:H− | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC EI122/63 | O111:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC E508/69 | O114:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC E74/68 | O125:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC KB1426 | O126:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC E63/68 | O128:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC E65/56 | O26:H− | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC D5301 | O128:H2 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC UR | O125ac:H− | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EPEC FEC 90632 | O2:H12 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EHEC 85-170 | O157:H7 | Human HUSb | + | − |

| EHEC EDL933 | O157:H7 | Human HUS | + | − |

| EHEC O15:H− | O15:H− | Human HUS | + | − |

| EHEC EH2 | O146:H2 | Human HUS | + | − |

| EHEC EH39 | O111:H− | Human HUS | + | + |

| EHEC E45035 | O111:H− | Human HUS | + | + |

| EHEC EH44 | O26 | Human HUS | + | + |

| EHEC EH6 | O26:H11 | Human HUS | + | + |

| EHEC EH1 | O26:H21 | Human diarrhea | + | + |

| EHEC EH68 | O147:H− | Human diarrhea | + | + |

Marker for the LEE pathogenicity island.

HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

Expression of lpfR141 in E. coli ORN103 and REPEC 83/39.

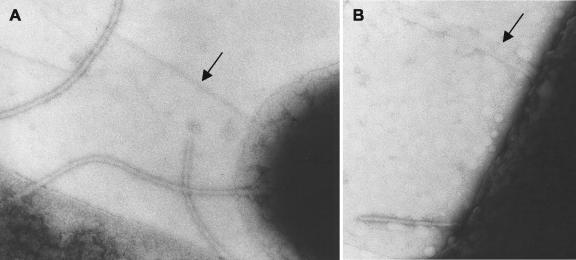

To visualize fimbrial structures encoded by lpfR141, we introduced pCR-Script carrying lpfR141 into E. coli ORN103, a fim deletion mutant of E. coli K-12 (29). Electron microscopic examination of negatively stained E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script:lpfR141) grown at 37°C revealed long, fine fimbriae extending from the bacterial surface that were absent from E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script) (Fig. 1). Unlike LPF from serovar Typhimurium, the fimbriae of E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script:lpfR141) were not uniformly polar, and one bacterium often bore several fimbriae on its surface. In addition, not all bacteria displayed fimbriae.

FIG. 1.

Expression of fimbriae in E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script:lpfR141) visualized by transmission electron microscopy. Magnifications, ×60,000 (A) ×75,000 (B). Bacteria were grown stationary in Luria broth overnight and stained with 1.0% ammonium molybdate. Arrows indicate long fine fimbriae.

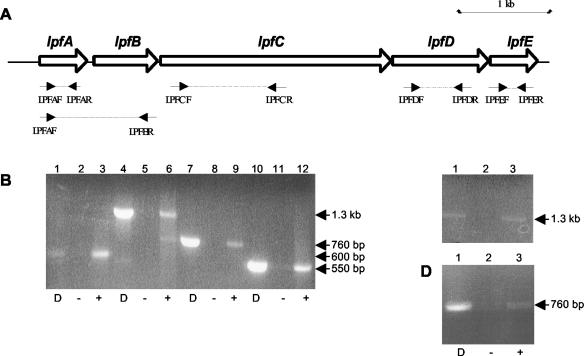

To determine whether lpfR141 was expressed in REPEC 83/39, whole-cell RNA was isolated from REPEC 83/39 grown to logarithmic growth phase and analyzed by RT-PCR. A range of primers covering each ORF and overlapping ORFs were used in an attempt to demonstrate the expression of each component of this gene cluster and to determine whether lpfA to -E were expressed as a polycistronic operon (Table 2). However, only lpfDR141 was expressed from lpfR141 of REPEC 83/39 by using a variety of culture conditions (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, we did demonstrate that E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script: lpfR141) expressed each of the five lpfR141 genes and that lpfAR141 and lpfBR141 were transcriptionally coupled (Fig. 2). These results also suggested that expression of lpfR141 in REPEC 83/39 was repressed in vitro and that the transfer of this locus to E. coli ORN103 facilitated transcription.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR analysis of lpfR141. (A) Schematic organization of the lpfR141 operon and location of primers used for RT-PCR. (B) RT-PCR analysis of E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script:lpfR141) cDNA. Lanes 1 to 3, primers LPFAF and LPFAR; lanes 4 to 6, primers LPFCF and LPFCR; lanes 7 to 9, primers LPFDF and LPFDR; lanes 10 to 12, primers LPFEF and LPFER. (C) RT-PCR analysis of E. coli ORN103(pCR-Script:lpfR141) cDNA. Lanes 1 to 3, primers LPFAF and LPFBR. (D) RT-PCR analysis of REPEC 83/39 cDNA. Lanes 1 to 3, primers LPFDF and LPFDR. D, DNA control PCR; + and −, presence or absence of the RT reaction, respectively. The sizes of the PCR products are indicated.

Contribution of lpfR141 and lpfR154 to adherence of REPEC 83/39 to epithelial cells.

To determine whether the REPEC lpf gene clusters played a role in the adherence of REPEC 83/39 to epithelial cells, we constructed single and double mutants of lpfR141 and lpfR154 in REPEC 83/39. To ensure that the lpf mutants of REPEC still carried known virulence markers, we used PCR to confirm that ral and eae were present, and we performed a FAS test to verify that the mutants still contained a functional LEE pathogenicity island capable of inducing the formation of A/E lesions (data not shown). In an attempt to establish an in vitro phenotype for the REPEC 83/39 lpf mutants, we performed quantitative adherence assays with CHO-K1 cells but found that there was no significant difference in the adherence of wild-type REPEC 83/39 (0.48% ± 0.32%), the lpfR141 mutant (0.32% ± 0.05%), the lpfR154 mutant (0.30% ± 0.07%), and the double mutant (0.42% ± 0.11%). Similar results were obtained with HeLa cells (data not shown). Hence, we were unable to establish an in vitro phenotype for either lpf gene cluster in REPEC 83/39.

Virulence of the REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR141/R154 mutants for rabbits.

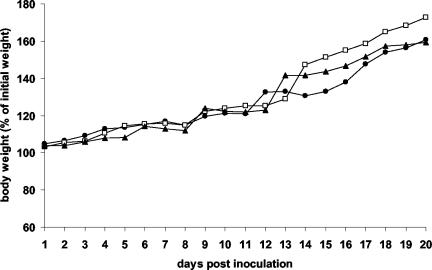

To determine whether lpfR141 and lpfR154 contributed to the virulence of REPEC for rabbits, the single REPEClpfR141 and double REPEClpfR141/R154 mutants were compared to wild-type REPEC 83/39 in the REPEC/rabbit model of infection. Three groups of five rabbits received 4 × 106 CFU of the test strains, and animals were observed for 20 days to monitor body weight, bacterial colonization, and severity of diarrhea. No significant difference in body weight or mortality rate between wild-type REPEC 83/39 and the lpf mutants was observed (Fig. 3 and Table 5). However, on the first 2 days after inoculation, both lpf mutants of REPEC 83/39 were shed in significantly lower numbers than wild-type REPEC 83/39 (Table 5). On day 1, the mean log10 CFU values per swab for REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR141/R154 were 1.26 ± 1.56 and 1.9 ± 1.35, respectively, which were significantly lower than the mean log10 CFU per swab for the wild-type strain of 3.6 ± 0.88 (P = 0.02 and 0.04, respectively [two-tailed, Student t test]). On day 2, the mean log10 CFU values per swab of REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR141/R154 were 2.76 ± 1.45 and 2.6 ± 1.55, respectively, compared to the mean log10 CFU per swab for the wild-type strain of 5.00 ± 1.35 (P = 0.04 and 0.03, respectively). No difference in excretion was observed between the single and double lpf mutants, however, suggesting that the reduction in fecal shedding of the mutants was mainly due to interruption of lpfR141. After day 2 postinoculation, there was no significant difference between excretion of wild-type REPEC 83/39 and the lpf mutants, indicating that the attenuation of the lpf mutants occurred only in the early stages of infection.

FIG. 3.

Effect of infection with various REPEC strains on rabbit body weight. The data presented are the mean percentages of initial weights for rabbits infected with wild-type REPEC 83/39 (▴), the single mutant REPEClpfR141 (□), or the double mutant REPEClpfR141/R154 (•). One death occurred on each of days 6, 9, and 13 for the REPEC 83/39 group; on days 8, 11, and 15 for the REPEClpfR141 group; and on days 9 and 14 for the REPEClpfR141/R154 group.

TABLE 5.

Log10 CFU per swab for rabbits infected with REPEC 83/39, REPEClpfR141, and REPEClpfR141/R154a

| Rabbit no. | Log10 CFU/swab at (days after infection):

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| 1 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 8.0 |

| 2 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 9.4 | † | |||||||||||

| 3 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 3.1 | <1 | <1 | 1.4 | <1 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 6.6 | † | |||||||

| 5 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | † | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.2 | † | |||||

| 7 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 2.2 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| 8 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 8.5 | † | |||||||||

| 9 | <1 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.0 | † | ||||||||||||

| 10 | <1 | 1.0 | <1 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 2.1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| 11 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| 12 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 9.1 | † | ||||||

| 13 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 2.0 |

| 14 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 8.1 | † | |||||||||||

| 15 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

Rabbits 1 to 5 were infected with wild-type REPEC 83/39, rabbits 6 to 10 were infected with the single REPEClpfR141 mutant, and rabbits 11 to 15 were infected with the double REPEClpfR141/R154 mutant. Values in boldface represent the presence of moderate to severe diarrhea. †, Rabbits died or were killed due to the severity of the illness.

The most striking difference between rabbits that received wild-type REPEC 83/39 and those that received the lpf mutants was in the development of severe diarrhea. Numerical values were assigned to each animal for severity of diarrhea and rabbits that experienced moderate (grade 3) or severe (grade 4) diarrhea are shown in Table 5. The proportion of observation days on which rabbits given the lpfR141 mutant strain experienced moderate to severe diarrhea was 9.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.5 to 19.0%), which was significantly less than the proportion for rabbits given the wild-type strain (38.3%; 95% CI = 24.5 to 53.6% [P < 0.001]). This difference was also significant between rabbits given the double lpfR141/R154 mutant (17.4% of observation days; 95% CI = 9.3 to 28.4%) and those which received the wild-type strain (P = 0.01) but not between rabbits which received either of the two lpf mutants (P > 0.1). These results indicate that rabbits infected with the wild-type strain suffered significantly more severe diarrhea than rabbits that received either the lpfR141 mutant strain or the double lpfR141/R154 mutant.

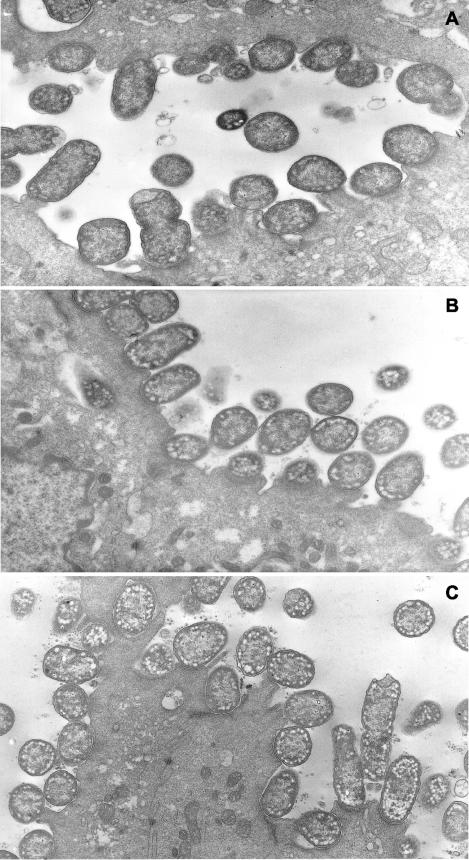

Histological examination of rabbits infected with REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR141/R154 mutants.

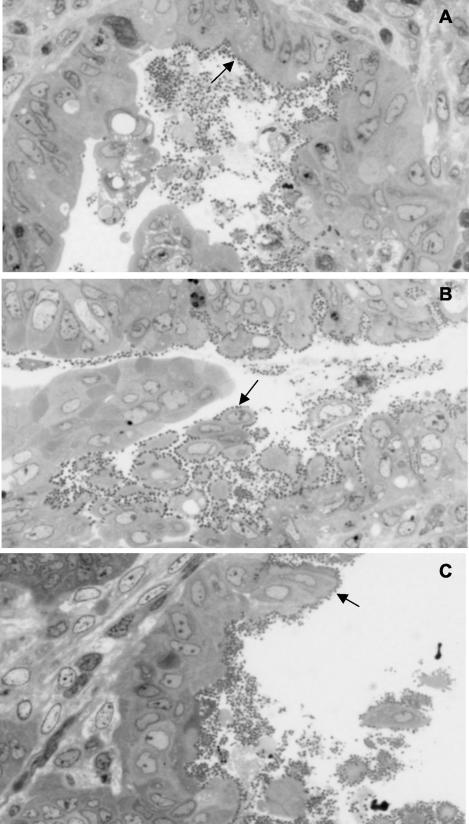

Intestinal sections taken from symptomatic rabbits that had been infected with one of the three test strains and killed on day 12 to 14 were examined by bright-field microscopy and transmission electron microscopy to determine the extent and location of bacterial adherence to the gut and A/E lesion formation. Intestinal sections were prepared from the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) and large intestine (colon and cecum). Despite the presence of high bacterial counts in all sections of the gut from individual animals (data not shown), intimate bacterial adherence to the gut mucosa was only observed in sections obtained from the colon (data not shown) and cecum (Fig. 4). At the time the biopsies were taken, namely, at the height of the illness, there was no difference in the level of adherence or tissue distribution of wild-type REPEC 83/39 and the two mutants, REPEClpfR141 and REPEClpfR141/R154. Moreover, wild-type REPEC 83/39 and both the single lpfR141 and double lpfR141/R154 mutants formed A/E lesions in the colon (data not shown) and cecum that were indistinguishable in morphology, location, and number among the three strains (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Light micrographs of 4-μm-thick sections of rabbit cecum stained with methylene blue from animals infected with wild-type REPEC 83/39 (A), the single mutant REPEClpfR141 (B), and the double mutant REPEClpfR141/R154 (C) sacrificed on days 13, 15, and 14 after inoculation, respectively. Arrows indicate bacteria closely adherent to the intestinal mucosa. Intimate adherence was not seen in stained cecal sections from uninfected control rabbits (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron micrographs of cecal mucosa from rabbits infected with wild-type REPEC 83/39 (A), the single mutant REPEClpfR141 (B), and the double mutant REPEClpfR141/R154 (C) sacrificed on days 13, 15, and 14 after inoculation, respectively. Note the presence of extensive A/E lesions in all fields. Magnification, ×10,000.

DISCUSSION

Although the mechanisms by which EPEC and EHEC cause diarrhea are not clear, it is evident that colonization of the gastrointestinal tract is central to the disease process, and several virulence factors involved in colonization of the host intestinal mucosa have been well characterized. The LEE pathogenicity islands of EPEC and REPEC encode all of the factors required for intimate adherence and A/E histopathology. In addition, the BFP expressed by EPEC is essential for colonization of the human intestinal mucosa and mediates bacterial microcolony formation in vitro and in vivo (5, 12). Although no analogous type IV pili are present in EHEC, lpfABCC′DE of EHEC O157:H7 was recently shown to contribute to bacterial microcolony formation in vitro (30). The contribution of this fimbrial gene cluster to the virulence of EHEC O157:H7 in vivo is not known.

The closely related rabbit A/E pathogen, REPEC, serves as a useful model for the study of EPEC and EHEC mediated disease. Strains of REPEC possess the LEE pathogenicity island but lack BFP and instead express strain-specific fimbrial adhesins (AF/R1, AF/R2, and Ral) that contribute to virulence (13, 28). In addition to these plasmid-encoded fimbriae, we have now identified two chromosomal O-islands in REPEC 83/39 that share predicted similarity and genome location with the LPF O-islands of EHEC O157:H7. One of these gene clusters, lpfR154, was identical to a fimbrial locus, lpfO113, that we recently identified in LEE-negative EHEC O113:H21 and which enhanced the ability of EHEC O113:H21 to adhere to CHO-K1 cells (8). The second O-island, lpfR141, encoded a novel sequence that was present in all REPEC strains examined, irrespective of serotype, and was also found in several human isolates of EHEC and EPEC. lpfR141 comprised five novel ORFs, lpfA to lpfE, that exhibited a similar genetic organization to O-island 141 from EHEC O157:H7 and the lpf gene cluster from serovar Typhimurium (3, 30). This included the presence of a putative stem-loop structure between lpfA and lpfB that is conserved among the three strains.

To determine whether lpfR141 was functional, we introduced the fimbrial gene cluster into a nonfimbriated E. coli strain, ORN103. This strain expressed all five genes and produced long, fine fimbriae on its surface, which were morphologically similar to LPF expressed by EHEC O157:H7 and serovar Typhimurium (3, 30). As observed for LPF from EHEC O157:H7, LPFR141 were not uniformly polar. Although we were unable to demonstrate that LPFR141 were produced by REPEC 83/39 in vitro, the expression of lpfDR141 in REPEC 83/39 was detected by RT-PCR. Nevertheless, we were unable to establish a phenotype for either REPEC LPF O-island in vitro since there was no apparent difference in the ability of wild-type REPEC 83/39 and the lpf mutants to adhere to cultured epithelial cells. The expression of lpfR141 in E. coli ORN103 also did not appear to increase the adherence of this strain in vitro (data not shown), although we have previously demonstrated that expression of lpfO113, which is identical to lpfR154, in E. coli ORN103, results in a twofold increase in bacterial adherence to CHO-K1 cells (8).

To determine whether there is a role for the LPF O-islands in the virulence of REPEC, we infected three groups of rabbits with a lpfR141 single mutant, a lpfR141/154 double mutant, and wild-type REPEC 83/39. Several disease parameters, including body weight, bacterial excretion, and diarrhea were monitored for 20 days to assess any alteration in the virulence of the lpf mutants compared to wild-type REPEC 83/39. In addition, the lpfR141 single mutant and the lpfR141/154 double mutant groups were compared to assess the relative contribution of lpfR154 to virulence. These studies revealed that animals that received the mutants did not suffer the same severity of diarrhea as the wild-type group, although they did lose comparable amounts of weight compared to rabbits infected with the wild-type strain, and appeared to suffer from wasting rather than typical watery diarrheal disease. Interestingly, rabbits that received the mutants showed histological evidence of A/E lesion formation that was identical in morphology, location, and extent compared to animals given the wild-type strain. These results indicated that the severity of diarrhea associated with infection by REPEC does not correspond with the extent of A/E histopathology and suggests that A/E lesion formation contributes to a wasting phenotype rather than to the development of severe diarrhea in the rabbit/REPEC model. These findings support other observations in our laboratory with a different mutant of strain 83/39 that the development of A/E lesions in rabbits does not correspond to the development of severe diarrhea (L. S. Taylor et al., unpublished data). Although transcomplementation of the mutants was not attempted in vivo, the construction of a single lpfR141 REPEC mutant, followed by the introduction of this mutation into the lpfR154 mutant to create the double mutant strongly suggested that the loss of phenotype we observed in rabbits was due to interruption of lpfR141. Our findings do not preclude a role for LPFR154 in disease, however, particularly if it acts in conjunction with or after LPFR141 in the pathogenic process.

Interestingly, rabbits infected with either the lpfR141 single mutant or the lpfR141/154 double mutant shed significantly fewer bacteria on days 1 and 2 postinoculation compared to rabbits infected with the parent strain. This suggests that lpfR141 may enhance early colonization of the rabbit intestine and, furthermore, that this step was important for the development of severe diarrhea. It is possible that the attenuation we observed was due to decreased bacterial adherence to a particular tissue type at these early time points, as demonstrated for serovar Typhimurium, for which LPF mediates adherence of the bacteria to murine Peyer's patches (4). Moreover, the majority of REPEC strains have been shown to colonize rabbit Peyer's patch epithelium, where they preferentially adhere to M cells (33). Although an investigation of the putative tissue tropism of LPFR141 was beyond the scope of the present study, an examination of the tissue specificity of wild-type REPEC 83/39 and the lpf mutants at early time points may reveal the basis of the attenuation observed for the lpfR141 mutants. Furthermore, the present study may provide some insight into the possible role of lpfABCC′DE in EHEC O157:H7 infection of humans.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Alfredo Torres and Jorge Girón for helpful discussions.

This study was supported in part by funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Monash University and the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute. H.J.N. is the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award.

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, L. M., C. P. Simmons, L. Rezmann, R. A. Strugnell, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 1997. Identification and characterization of a K88- and CS31A-like operon of a rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain which encodes fimbriae involved in the colonization of rabbit intestine. Infect. Immun. 65:5222-5230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adu-Bobie, J., G. Frankel, C. Bain, A. G. Goncalves, L. R. Trabulsi, G. Douce, S. Knutton, and G. Dougan. 1998. Detection of intimins alpha, beta, gamma, and delta, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:662-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumler, A. J., and F. Heffron. 1995. Identification and sequence analysis of lpfABCDE, a putative fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 177:2087-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, and F. Heffron. 1996. The lpf fimbrial operon mediates adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to murine Peyer's patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:279-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieber, D., S. W. Ramer, C. Y. Wu, W. J. Murray, T. Tobe, R. Fernandez, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1998. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 280:2114-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg, M. S., J. A. Giron, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 1992. A plasmid-encoded type IV fimbrial gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli associated with localized adherence. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3427-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doughty, S., J. Sloan, V. Bennett-Wood, M. Robertson, R. M. Robins-Browne, and E. L. Hartland. 2002. Identification of a novel fimbrial gene cluster related to long polar fimbriae in locus of enterocyte effacement-negative strains of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70:6761-6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott, S. J., L. A. Wainwright, T. K. McDaniel, K. G. Jarvis, Y. K. Deng, L. C. Lai, B. P. McNamara, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1998. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, I. Rosenshine, G. Dougan, J. B. Kaper, and S. Knutton. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30:911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi, T., K. Makino, M. Ohnishi, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, K. Yokoyama, C. G. Han, E. Ohtsubo, K. Nakayama, T. Murata, M. Tanaka, T. Tobe, T. Iida, H. Takami, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, N. Ogasawara, T. Yasunaga, S. Kuhara, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, and H. Shinagawa. 2001. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 8:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hicks, S., G. Frankel, J. B. Kaper, G. Dougan, and A. D. Phillips. 1998. Role of intimin and bundle-forming pili in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion to pediatric intestinal tissue in vitro. Infect. Immun. 66:1570-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karaolis, D. K., T. K. McDaniel, J. B. Kaper, and E. C. Boedeker. 1997. Cloning of the RDEC-1 locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) and functional analysis of the phenotype on HEp-2 cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 412:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenny, B. 2002. Mechanism of action of EPEC type III effector molecules. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:469-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knutton, S., T. Baldwin, P. H. Williams, and A. S. McNeish. 1989. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1290-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krejany, E. O., T. H. Grant, V. Bennett-Wood, L. M. Adams, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2000. Contribution of plasmid-encoded fimbriae and intimin to capacity of rabbit-specific enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to attach to and colonize rabbit intestine. Infect. Immun. 68:6472-6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDaniel, T. K., K. G. Jarvis, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1664-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon, H. W., S. C. Whipp, R. A. Argenzio, M. M. Levine, and R. A. Giannella. 1983. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect. Immun. 41:1340-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholls, L., T. H. Grant, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2000. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 35:275-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson, T. L., and A. J. Baumler. 2001. Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium elicits cross-immunity against a Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis strain expressing LP fimbriae from the lac promoter. Infect. Immun. 69:204-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pillien, F., C. Chalareng, M. Boury, C. Tasca, J. de Rycke, and A. Milon. 1996. Role of Adhesive Factor/Rabbit 2 in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O103 diarrhea of weaned rabbit. Vet. Microbiol. 50:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robins-Browne, R. M. 1987. Traditional enteropathogenic Escherichia coli of infantile diarrhea. Rev. Infect. Dis. 9:28-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins-Browne, R. M., A. M. Tokhi, L. M. Adams, V. Bennett-Wood, A. V. Moisidis, E. O. Krejany, and L. E. O'Gorman. 1994. Adherence characteristics of attaching and effacing strains of Escherichia coli from rabbits. Infect. Immun. 62:1584-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Laboratory Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Schauer, D. B., and S. Falkow. 1993. Attaching and effacing locus of a Citrobacter freundii biotype that causes transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect. Immun. 61:2486-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tauschek, M., R. A. Strugnell, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2002. Characterization and evidence of mobilization of the LEE pathogenicity island of rabbit-specific strains of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1533-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tewari, R., T. Ikeda, R. Malaviya, J. I. MacGregor, J. R. Little, S. J. Hultgren, and S. N. Abraham. 1994. The PapG tip adhesin of P fimbriae protects Escherichia coli from neutrophil bactericidal activity. Infect. Immun. 62:5296-5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres, A. G., J. A. Giron, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, F. R. Blattner, F. Avelino-Flores, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. Identification and characterization of lpfABCC′DE, a fimbrial operon of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 70:5416-5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu, X., I. Nisan, C. Yona, E. Hanski, and I. Rosenshine. 2003. EspH, a new cytoskeleton-modulating effector of enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 47:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vial, P. A., J. J. Mathewson, H. L. DuPont, L. Guers, and M. M. Levine. 1990. Comparison of two assay methods for patterns of adherence to HEp-2 cells of Escherichia coli from patients with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:882-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Moll, L. K., and J. R. Cantey. 1997. Peyer's patch adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 65:3788-3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf, M. K., and E. C. Boedeker. 1990. Cloning of the genes for AF/R1 pili from rabbit enteroadherent Escherichia coli RDEC-1 and DNA sequence of the major structural subunit. Infect. Immun. 58:1124-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu, J., and J. B. Kaper. 1992. Cloning and characterization of the eae gene of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 6:411-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]