Introduction

Early electron microscopic studies of the structure of the nucleus in vertebrate cells identified an electron dense layer, the fibrous lamina (Fawcett 1966) or zonula nucleum limitans (Patrizi and Poger, 1967), underlying the inner nuclear membrane. Biochemical subfractionation of isolated rat liver nuclei produced a pore complex-lamina fraction containing nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) (Aaronson and Blobel, 1975, Dwyer and Blobel, 1976) linked together by a submembranous network structure corresponding to the region identified by microscopy (Dwyer and Blobel, 1976). Further characterization of this substructure by SDS-PAGE revealed that it contained three major and several minor proteins (Dwyer and Blobel, 1976, Gerace et al., 1978). The three major proteins subsequently were shown to be immunologically related and were named lamins A, B and C according to their migration in SDS gels (70-kD, 67-kD and 60-kD, respectively (Gerace and Blobel, 1980, Gerace, Blum, 1978)). cDNA cloning and sequencing of the mRNAs for each lamin isoform along with biochemical analyses of purified proteins and electron microscopy of Xenopus oocyte nuclear envelopes led to the classification of lamins as type V intermediate filament proteins (Aebi et al., 1986, Fisher et al., 1986, Goldman et al., 1986, McKeon et al., 1986). Lamins are categorized into two types, A and B, based on biochemical and sequence characteristics. The lamin genes are restricted to metazoans (Melcer et al., 2007), with lower phyla having one B-type gene and higher organisms possessing at least one gene of each type. Invertebrates have only a single B-type lamin gene, with some exceptions such as Drosophila, which has one B-type (lamin Dm0) and one A-type lamin (lamin C) gene. Most vertebrates have one A-type lamin and two B-type lamin genes except for Xenopus, which has three B-type genes (Stick, 1994). In mammalian cells, four A-type lamin proteins are produced from LMNA by alternative splicing: the predominant isoforms lamin A (LA) and lamin C (LC)(Lin and Worman, 1993), a minor isoform LAΔ10 (Machiels et al., 1996), and a germ cell specific isoform LC2 (Alsheimer and Benavente, 1996, Furukawa et al., 1994). The two B-type lamin proteins are produced from LMNB1, lamin B1 (LB1) (Lin and Worman, 1995, Maeno et al., 1995), and LMNB2, lamin B2 (LB2) (Biamonti et al., 1992, Hoger et al., 1990).

In this review, we discuss the differences in the structure and properties of the mammalian A- and B-type lamins and the implications of these differences in lamin functions.

Differential expression of lamins

One clue to possible differences in A- and B-type lamin functions is in their differential expression during development. For example, a B-type lamin is expressed throughout embryogenesis, whereas LA and LC are not expressed until the tissue differentiation stage of development (Rober et al., 1989, Stewart and Burke, 1987). In adults, both A- and B-type lamins appear to be expressed in all cells with the exception of T-cells and B-cells which express only B-type lamins. The regulated expression of A-and B-type lamins is also evident during the differentiation of stem cells in culture. For example, undifferentiated human and mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells lack lamins A and C, but express lamins B1 and B2 (Constantinescu et al., 2006).

Modification of the A- and B-type lamin carboxyl terminus by farnesylation

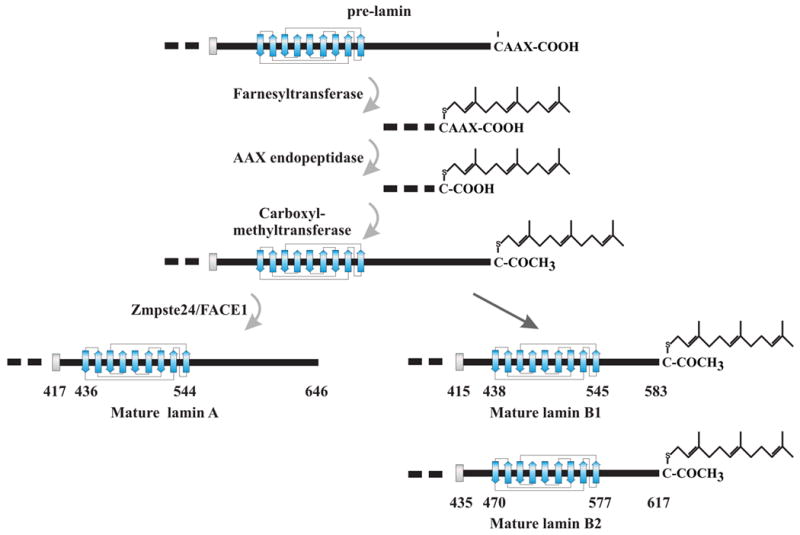

The overall structure of the A- and B-type lamins is similar, but each are modified differently by farnesylation of the carboxyl terminus. LA, LB1 and LB2 are translated with a carboxyl terminal -CAAX sequence that is a consensus sequence for the addition of a farnesyl lipid to the proteins. LC lacks a –CAAX sequence and its carboxyl terminus is not further modified after synthesis. The sequential processing of the –CAAX sequence is initiated by the addition of the C15 lipid, farnesyl, to the cysteine residue by a farnesyltransferase (Zhang and Casey, 1996). Following the addition of farnesyl, the three terminal amino acids are removed by a specific protease. For LA, the Zinc metalloprotease related to Ste24p, Zmpste24 (also known as FACE1) is used. However, the residues in B-type lamins are removed by a different protease, Rce1 (Ras-converting enzyme 1 (Figure 1). The utilization of different proteases to process the carboxyl terminus of A- and B-type lamins suggests that the two types of lamins may be processed in different locations within the environment of the nuclear envelope. The final modification step for all farnesylated lamins is the carboxymethylation of the alpha carboxyl of the terminal cysteine by isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (Icmt) (Winter-Vann and Casey, 2005). In LA, but not in the B-type lamins, a second protease cleavage site for Zmpste24/FACE1 14 residues upstream of the farnesylated cysteine is cleaved removing the farnesyl residue attached to the 15 amino acid peptide. The location of lamin carboxyl terminal processing is unknown, but is presumed to take place within the nucleus. The presence of the farnesyl residue attached to B-type lamins suggests that they may be more closely associated with the inner nuclear membrane than LA or LC (Nigg et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

Modification of the lamin carboxyl terminus. LA, LB1 and LB2 are synthesized as pre-proteins that are modified by farnesylation of the carboxyl terminus. These steps occurs sequentially beginning with the addition of farnesyl to the cysteine residue of the –CAAX sequence, followed by removal of the three terminal amino acids and carboxymethylation of the cysteine. In LA, an additional 15 amino acids are removed by protease cleavage along with the attached farnesyl moiety. The B-type lamins remain permanently farnesylated.

The A- and B-type lamins form separate but interacting networks

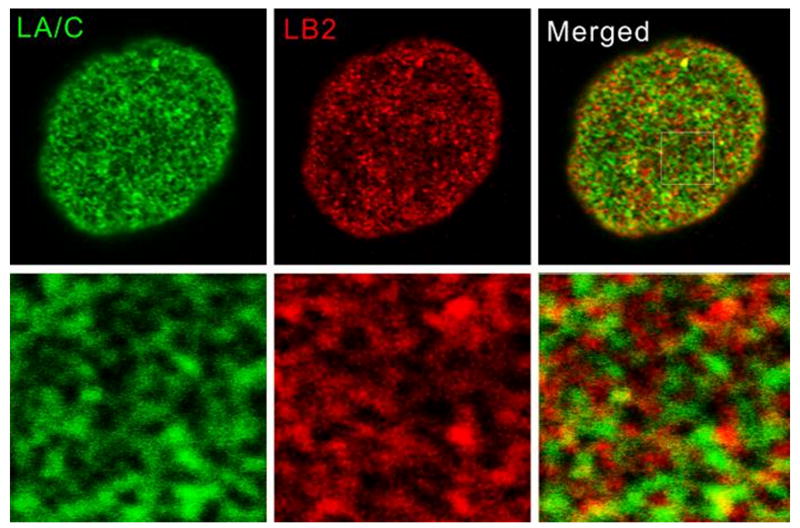

Several independent lines of experiments suggest that the A- and B-type lamins form separate filamentous networks in the lamina of somatic cells. Imaging of the lamin structure in somatic cells has proven to be problematic due to the complex organization of the somatic cell nuclear envelope and the tight association of chromatin fibers with the lamina. Using whole mount electron microscopy of Xenopus oocyte nuclei expressing somatic A- and B-type lamins, Goldberg and coworkers (Goldberg et al., 2008) demonstrated that LA and LB2 form different types of filaments in separate intranuclear compartments. LB2 formed irregular wavy filaments associated with intranuclear membrane structures induced by expression of LB2. In contrast, LA formed thick multilayered assemblies of filaments closely associated with the endogenous LB3 lamina. We have employed high resolution confocal microscopy to localize A- and B-type lamins in somatic cells and demonstrate that each type of lamin forms a distinct meshwork structure with a relatively small number of points of colocalization (Shimi et al., 2008) (Figure 2). Furthermore, silencing the expression of LB1 in HeLa cells using shRNA leads to the formation of extensively enlarged lamin A/C meshworks and NE blebs which lack lamin B2 and NPCs (Shimi, Pfleghaar, 2008). This suggests that the structure of the A-type lamin meshwork is dependent on the integrity of the LB1 meshwork. Fibroblasts derived from LMNA-/- mouse embryos (MEFs) or a limb girdle muscular dystrophy patient with a homozygous nonsense mutation in LMNA contain abnormally shaped nuclei with a significant number of NE blebs lacking B-type lamins and NPCs. In addition, the LA/C meshwork in the NE of LMNBΔ/ΔMEFs exhibits a dramatic increase in mesh size (Vergnes et al., 2004). Additional evidence for interaction between these two lamin meshworks comes from studies using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) in combination with time domain fluorescence lifetime imaging and high resolution confocal immunofluorescence (Delbarre et al., 2006, Moir et al., 2000, Shimi, Pfleghaar, 2008).

Figure 2.

Separation of the A- and B-type lamin meshworks in the nuclear lamina. Immunofluorescence microscopy of LA and LB1 shows that each lamin forms a meshwork like structure as seen in this view focused on the nuclear surface. An overlay of the two images demonstrates that they are distinct structures with a few points of overlap.

A small but significant fraction of both A- and B-type lamins are also present throughout the nuclear interior during interphase. Some of these internal lamins may be nascent proteins that were recently transported from the cytoplasm and are waiting to be assembled into the lamina (Goldman et al., 1992, Lutz et al., 1992), but most seem to be resident in this compartment. These internal lamins are likely to be involved in several nuclear functions including DNA replication and repair or transcription. The mobility of the internal A- and B-type lamins suggests that they participate in different types of interactions. For example, internal B-type lamins appear to be relatively static, similar to those in the lamina, while the A-type lamins are much more dynamic, and A-type lamins are more easily extracted than B-type lamins. Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) measurements of GFP-tagged LA and LB1 showed that nucleoplasmic LA is highly mobile, whereas LB1 is mainly immobile (Shimi, Pfleghaar, 2008). This suggests that the internal B-type lamins are tightly associated with other relatively immobile structures such as chromatin. Although the A- and B-type lamins within the nucleus appear to be separated based on biochemical and biophysical criteria, they also appear to interact. This is best supported by the observation that reducing the amount of LB1 by shRNA-mediated silencing increases the rate of mobility of a large fraction of nucleoplasmic lamin A (Shimi, Pfleghaar, 2008). This suggests that the A- and B-type lamins within the nuclear interior, like the lamins in the lamina, form separate yet interacting structures. Obviously, it will be of great interest in the future to determine the specific functions of these nucleoplasmic lamins.

Separation of the A- and B- type lamins during mitosis

A graphic example of the different properties of the A- and B-type lamins is evident during mitosis. At the onset of prophase, the nuclear lamins become phosphorylated and disassemble, with the A-type lamins dispersing into the cytoplasm in a freely diffusible state and the B-type lamins remaining associated with the nuclear membranes as they are dispersed into the endoplasmic reticulum (Ellenberg et al., 1997, Gerace and Blobel, 1980). This stable association of B-type lamins with membranes during mitosis is likely due to the presence of the farnesyl moiety attached to the carboxyl terminus. The idea that farnesylation mediates the interaction of lamins with membranes during mitosis is supported by the finding that the permanently farnesylated mutant form of lamin A, progerin, expressed in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria also remains associated with the endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis (Cao et al., 2007, Dechat et al., 2007). The A- and B-type lamins also show differences in their temporal order of assembly into the NE at the completion of mitosis. B-type lamins accumulate around the chromosomes as the nuclear membranes that had dispersed during prophase surround telophase chromosomes (Dechat et al., 2004). The bulk of the A-type lamins, however, are only assembled into the NE after the nuclear membranes have fully enclosed the chromosome mass and nuclear transport is re-established (Moir, Yoon, 2000). In some cells, A-type lamins will persist in the nucleoplasm throughout early G1 and are only gradually incorporated into the lamina.

Lamins and Chromatin

In recent years, evidence has begun to accumulate that the A- and B-type lamins associate with different types of chromatin. As described in the earlier section on the separation of lamin networks, we have found that silencing LB1 expression in HeLa cells leads to the formation of NE blebs that are enriched in LA and LC, but lack LB2. The chromatin associated with these NE blebs is mainly euchromatic and is comprised of gene rich chromosome regions. This suggests that A-type lamins are preferentially associated with gene-rich regions of active chromatin (Shimi, Pfleghaar, 2008). In contrast, LB1 seems to be mainly associated with the borders of regions with low gene density and low transcriptional activity. Using DamID labeling to identify LB1-associated chromatin, van Steensel and coworkers have shown that genomic domains of 50kb to 10Mb in size are bounded by regions that are enriched in interactions with LB1 (Guelen et al., 2008). These domains called lamin associated domains or LADs may represent the heterochromatin frequently seen closely apposed to the inner NE in many somatic cells. Together, these findings suggest that the differential expression of lamins through development and in different cell types is involved in the regulation of gene expression by mediating chromatin interactions at the nuclear envelope.

Summary

Based upon the information available on the differences in the A- and B- type lamins, it is becoming obvious that they form different structures and carry out different functions. However, it is also important to note that these two types of nuclear lamins are interdependent and that alterations in one lamin network can have an impact on the structure and function of the other. Future studies should provide new insights into the mechanisms responsible for the interactions among the different types of lamins.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaronson RP, Blobel G. Isolation of nuclear pore complexes in association with a lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1007–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi U, Cohn J, Buhle L, Gerace L. The nuclear lamina is a meshwork of intermediate-type filaments. Nature. 1986;323:560–4. doi: 10.1038/323560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsheimer M, Benavente R. Change of karyoskeleton during mammalian spermatogenesis: expression pattern of nuclear lamin C2 and its regulation. Exp Cell Res. 1996;228:181–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biamonti G, Giacca M, Perini G, Contreas G, Zentilin L, Weighardt F, et al. The gene for a novel human lamin maps at a highly transcribed locus of chromosome 19 which replicates at the onset of S-phase. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3499–506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K, Capell BC, Erdos MR, Djabali K, Collins FS. A lamin A protein isoform overexpressed in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome interferes with mitosis in progeria and normal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4949–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611640104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu D, Gray HL, Sammak PJ, Schatten GP, Csoka AB. Lamin A/C expression is a marker of mouse and human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:177–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Gajewski A, Korbei B, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Haraguchi T, et al. LAP2alpha and BAF transiently localize to telomeres and specific regions on chromatin during nuclear assembly. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6117–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Shimi T, Adam SA, Rusinol AE, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, et al. Alterations in mitosis and cell cycle progression caused by a mutant lamin A known to accelerate human aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4955–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbarre E, Tramier M, Coppey-Moisan M, Gaillard C, Courvalin JC, Buendia B. The truncated prelamin A in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome alters segregation of A-type and B-type lamin homopolymers. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1113–22. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer N, Blobel G. A modified procedure for the isolation of a pore complex-lamina fraction from rat liver nuclei. J Cell Biol. 1976;70:581–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.70.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg J, Siggia ED, Moreira JE, Smith CL, Presley JF, Worman HJ, et al. Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1193–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DZ, Chaudhary N, Blobel G. cDNA sequencing of nuclear lamins A and C reveals primary and secondary structural homology to intermediate filament proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:6450–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Inagaki H, Hotta Y. Identification and cloning of an mRNA coding for a germ cell-specific A-type lamin in mice. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:426–30. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Blobel G. The nuclear envelope lamina is reversibly depolymerized during mitosis. Cell. 1980;19:277–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L, Blum A, Blobel G. Immunocytochemical localization of the major polypeptides of the nuclear pore complex-lamina fraction. Interphase and mitotic distribution. J Cell Biol. 1978;79:546–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.79.2.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MW, Huttenlauch I, Hutchison CJ, Stick R. Filaments made from A- and B-type lamins differ in structure and organization. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:215–25. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AE, Maul G, Steinert PM, Yang HY, Goldman RD. Keratin-like proteins that coisolate with intermediate filaments of BHK-21 cells are nuclear lamins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:3839–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AE, Moir RD, Montag-Lowy M, Stewart M, Goldman RD. Pathway of incorporation of microinjected lamin A into the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:725–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008;453:948–51. doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoger TH, Zatloukal K, Waizenegger I, Krohne G. Characterization of a second highly conserved B-type lamin present in cells previously thought to contain only a single B-type lamin. Chromosoma. 1990;100:67–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00337604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Worman HJ. Structural organization of the human gene encoding nuclear lamin A and nuclear lamin C. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F, Worman HJ. Structural organization of the human gene (LMNB1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics. 1995;27:230–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz RJ, Trujillo MA, Denham KS, Wenger L, Sinensky M. Nucleoplasmic localization of prelamin A: implications for prenylation-dependent lamin A assembly into the nuclear lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3000–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machiels BM, Zorenc AH, Endert JM, Kuijpers HJ, van Eys GJ, Ramaekers FC, et al. An alternative splicing product of the lamin A/C gene lacks exon 10. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9249–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeno H, Sugimoto K, Nakajima N. Genomic structure of the mouse gene (Lmnb1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics. 1995;30:342–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeon FD, Kirschner MW, Caput D. Homologies in both primary and secondary structure between nuclear envelope and intermediate filament proteins. Nature. 1986;319:463–8. doi: 10.1038/319463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcer S, Gruenbaum Y, Krohne G. Invertebrate lamins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moir RD, Yoon M, Khuon S, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamins A and B1: different pathways of assembly during nuclear envelope formation in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1155–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA, Kitten GT, Vorburger K. Targeting lamin proteins to the nuclear envelope: the role of CaaX box modifications. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20:500–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0200500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrizi G, Poger M. The ultrastructure of the nuclear periphery. The zonula nucleum limitans. Journal of ultrastructure research. 1967;17:127–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rober RA, Weber K, Osborn M. Differential timing of nuclear lamin A/C expression in the various organs of the mouse embryo and the young animal: a developmental study. Development. 1989;105:365–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimi T, Pfleghaar K, Kojima S, Pack CG, Solovei I, Goldman AE, et al. The A- and B-type nuclear lamin networks: microdomains involved in chromatin organization and transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3409–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, Burke B. Teratocarcinoma stem cells and early mouse embryos contain only a single major lamin polypeptide closely resembling lamin B. Cell. 1987;51:383–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stick R. The gene structure of B-type nuclear lamins of Xenopus laevis: implications for the evolution of the vertebrate lamin family. Chromosome Res. 1994;2:376–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01552797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10428–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter-Vann AM, Casey PJ. Post-prenylation-processing enzymes as new targets in oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:405–12. doi: 10.1038/nrc1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FL, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:241–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]