Abstract

Background

Burnout is a common problem for interns and residents. It may be related to medical error, but little is known about this relationship. The purpose of this study was to determine the association between burnout and perceived medical errors among interns and residents.

Methods

The study group consisted of interns and residents working in a university hospital in Busan. Data were provided by 86 (58.5%) of 147 interns and residents. They completed a questionnaire including self-assessment of medical errors, a linear analog self-assessment of overall quality of life (QOL), fatigue, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, and a validated depression screening tool.

Results

According to univariate logistic regression analyses, there was an association between perceived medical errors and fatigue (odds ratio [OR], 1.37 per unit increase; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12 to 1.69; P < 0.003) and ESS scores (OR, 1.13 per unit increase; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.23; P < 0.009). Perceived medical errors were also associated with burnout (ORs per 1-unit change; emotional exhaustion OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.13; P < 0.005; depersonalization OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.21; P < 0.013), a negative depression screen (OR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11 to 0.76; P < 0.013), and overall QOL (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.98; P < 0.033). In multivariate logistic regression analyses, an association was identified between perceived medical errors and emotional exhaustion (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.11; P < 0.046) when adjusted for ESS, and depersonalization (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.19; P < 0.04) when adjusted for fatigue.

Conclusion

Higher levels of burnout among interns and residents were associated with perceived medical errors.

Keywords: Burnout, Resident, Medical Errors

INTRODUCTION

Becoming a physician requires a high level of medical knowledge and skill in order to deal with issues of life and death, and residents must pass intense training courses to acquire the required skills. A resident receives training in an educational hospital or medical institute in order to acquire a license as a medical specialist. According to data collected by the Korean Medical Association, there were 14,633 residents as of December 31, 2008, accounting for 18.6% of the 78,518 total physicians working in the medical field. Most residents work in educational hospitals, where they often play important roles as primary physicians. Like students of medical schools or graduate schools of medicine, they are also in training to become qualified medical specialists. However, residents work in educational hospitals and have a lower economic status and social position relative to the larger community of physicians. Residents often commit a variety of medical errors because of heavy job stress and fatigue. In addition, hospitals often fail to provide management to reduce job stress, and residents often feel that they cannot state their needs due to their position as trainees. Hospitals often consider them as low-cost operating labor and consider the improvement of systems or facilities associated with medical training as a hindrance to hospital operations, and therefore little effort is made to improve conditions for residents and their training program.

Medical errors and the safety of patients are important issues for both patients and physicians. In the US in 1999, it was reported that about 100,000 patients died from previously preventable side effects and this has significant implications for both physicians and patients.1) Studies regarding medical errors report that resident fatigue and sleepiness are major factors in medical errors.1-4) Another study reports that resident burnout from stress is a major cause of self-reported medical errors.5) Continued and repeated stress results in burnout6) by inducing physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion. It is easy to understand why fatigue may cause medical errors. However, because fatigue or sleepiness may affect burnout, there is a need for studies solely on burnout apart from fatigue and sleepiness. This study intends to help improve both patient safety and resident training conditions by understanding the relationship between resident burnout and subsequent medical errors.

METHODS

1. Subjects and Study Period

In order to investigate the relationship between resident burnout and self-reported medical errors, a survey of 147 residents in a university hospital in Busan was performed from July to August, 2010. Residents completed a self-answer questionnaire. Among the 147 distributed questionnaires, 61 were not returned. Therefore, a total of 86 questionnaires were collected, yielding a response rate of 58.5%.

2. Methods

Self-reported medical errors were assessed by the question, "have you committed a medical error in the last three months?" Medical errors were defined as subjective errors recognized by residents rather than events that harmed patients, and this was explained in the questionnaire. Fatigue was estimated using linear analog self-assessment (LASA) questions. Respondents measured their fatigue from 1 (not fatigued) to 10 (always fatigued); a higher score corresponded to greater fatigue. Sleepiness was assessed with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. This tool measures daytime sleepiness according to eight items for which respondents were instructed to rate on a Likert scale from 0 (not sleepy at all) to 3 (very sleepy). A total score higher than 10 points was considered indicative of daytime sleepiness.7,8) Quality of life (QOL) was assessed with LASA questions by measuring the overall quality of life from 1 (very bad) to 10 (very good).9-11) Burnout was defined as a feeling of continued and repeated emotional pressure. Maslach et al.12) suggested that the sub-areas of burnout consist of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced professional efficacy or personal accomplishment. Resident burnout was measured with a burnout assessment tool that had been translated and used in a previous study of the factors affecting social worker exhaustion.13,14) A total of 22 questions (9 questions for emotional exhaustion, 8 questions for personal accomplishment, and 5 questions for depersonalization) assessed burnout, and each was measured on a 7-point Likert scale from "1: very weak, scarcely felt" to "7: very strong, very frequently felt." The Maslach burnout inventory (MBI) scale is a tool produced by Maslach et al.12) in 1981 for measuring burnout and has proven both reliable and valid in estimating the degree of burnout experienced by subjects. In addition, because the fact that this tool has been used in a number of previous studies across many occupations, it may provide a basis for interpreting results of this case.15-18) In the screening test for depression, two questions provided by Spitzer et al.19) were used.20) These two questions were "1) during the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?" and "2) during the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?" If the subject answered "yes" to either of these questions, the screening was considered positive for depression. In previous studies, this screening test was proved to be reasonable compared to other screening tests for depression.21, 22)

3. Analysis

The t-test and the chi-square test were used to identify the relationship between self-reported medical errors of residents and fatigue, daytime sleepiness, quality of life, burnout, and depression. In order to determine whether burnout is associated with self-reported medical errors, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

1. General Features of Subjects

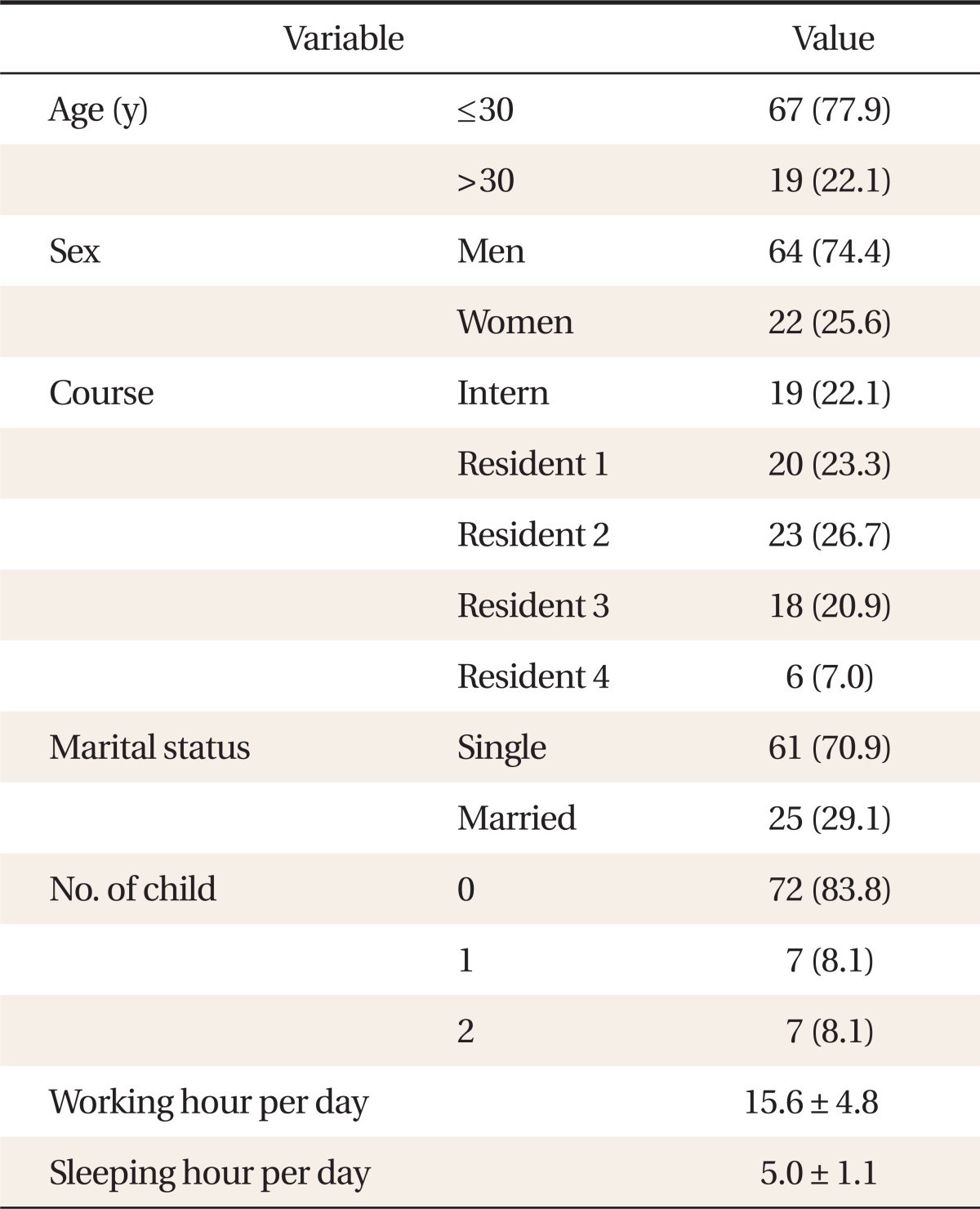

Data were provided by 86 of 147 interns and residents and the characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 86)

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD.

2. Comparison of Self-Reported Medical Errors with Respect to Survey Parameters

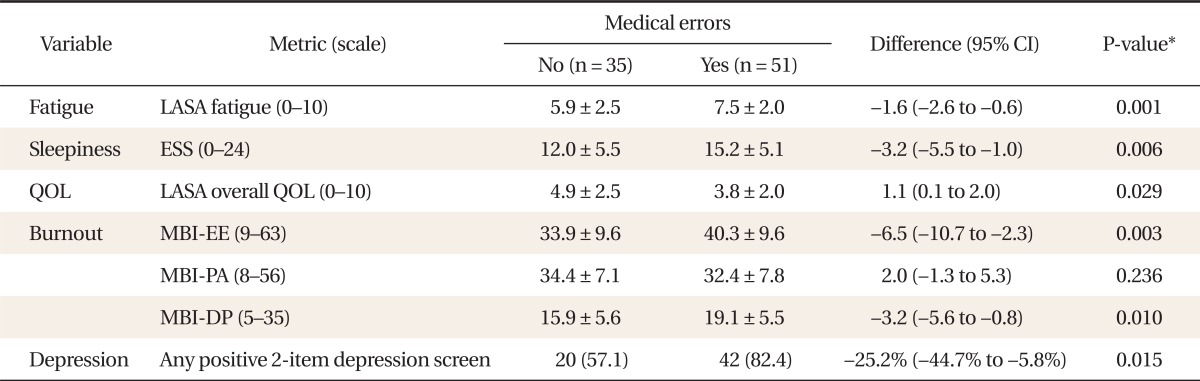

In this study, 51 (59%) subjects reported medical errors. Summary measures to identify general associations between self-reported medical errors and degree of fatigue, sleepiness, QOL, burnout, and symptoms of depression are shown in Table 2. Interns and residents who reported medical errors experienced greater fatigue and sleepiness and had significantly lower overall QOL and higher levels of burnout as evidenced by increased depersonalization and emotional exhaustion. In the screening test for depression, 42 (82.4%) of 51 subjects who reported medical errors were positive in the depression screening and 20 (57.1%) of 35 subjects who reported no medical errors were positive in the screening test for depression.

Table 2.

Comparison of residents reporting no perceived errors vs. reporting perceived errors

Values are presented as mean ± SD or number (%).

CI: confidence interval, LASA: linear analog self-assessment, ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, QOL: quality of life, MBI-EE: Maslach burnout inventory-emotional exhaustion, MBI-PA: Maslach burnout inventory-personal accomplishment, MBI-DP: Maslach burnout inventory-depersonalization.

*Obtained by t-test or chi-square test.

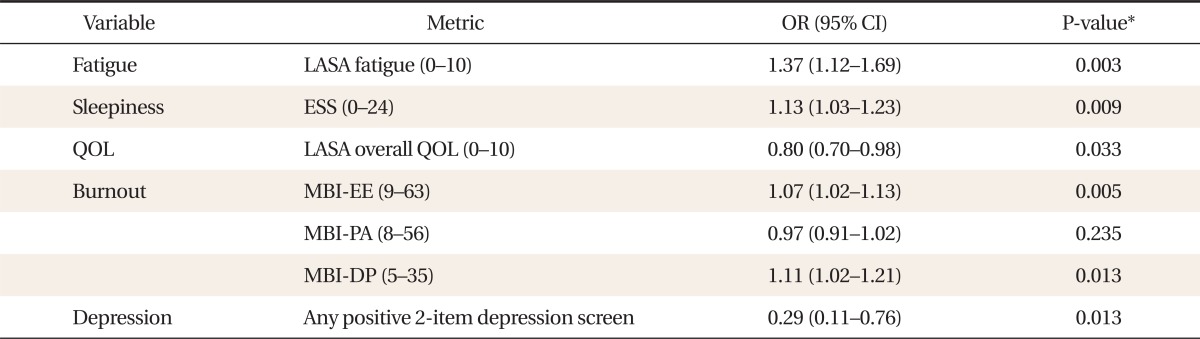

3. Univariate Analysis for Factors Related to Medical Errors

In the univariate logistic regression analysis of medical errors, it was found that the odds ratio (OR) of fatigue was 1.37 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12 to 1.69) and the OR of daytime sleepiness was 1.13 (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.23). The OR of quality of life was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.70 to 0.98) and in the analysis of burnout, the OR of emotional exhaustion was 1.07 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.13), the OR of depersonalization was 1.11 (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.21), and the OR of personal accomplishment was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.91 to 1.02). However, the results for personal accomplishment were not found to be statistically significant. For those subjects who were found to be negative for depression, the OR was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.11 to 0.76) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted association of fatigue, sleepiness, QOL, burnout, and symptoms of depression with self-reported medical errors (n = 86)

QOL: quality of life, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, LASA: linear analog self-assessment, ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, MBI: Maslach burnout inventory, EE: emotional exhaustion, PA: personal accomplishment, DP: depersonalization.

*Univariate logistic regression analysis.

4. Multivariate Analysis for Medical Error-Related Factors Adjusted for Sleepiness and Fatigue

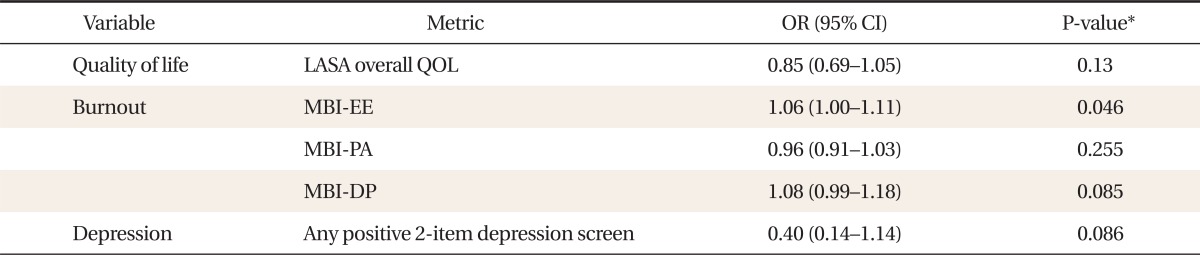

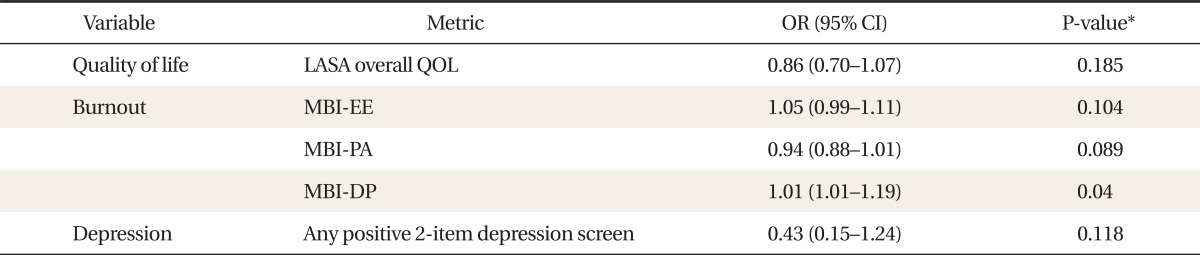

After adjusting for sleepiness and fatigue, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. When controlling for daytime sleepiness, the OR of emotional exhaustion was 1.06 (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.11) and when controlling for fatigue, the OR of depersonalization was 1.01 (95% CI, 1.01 to 1.19) (Tables 4, 5).

Table 4.

Adjusted association of fatigue, sleepiness, QOL, burnout, and depression symptoms with self-reported medical errors (variable adjusted for sleepiness)

QOL: quality of life, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, LASA: linear analog self-assessment, MBI: Maslach burnout inventory, EE: emotional exhaustion, PA: personal accomplishment, DP: depersonalization.

*Multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for sleepiness.

Table 5.

Adjusted association of fatigue, sleepiness, QOL, burnout, and depression symptoms with self-reported medical errors (variable adjusted for fatigue)

QOL: quality of life; OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval, LASA: linear analog self-assessment, MBI: Maslach burnout inventory, EE: emotional exhaustion, PA: personal accomplishment, DP: depersonalization.

*Multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for fatigue.

DISCUSSION

Although stress experienced by residents in hospitals is unavoidable, the degree of stress may be greater than that experienced by those in other professions.23) Some amount of stress may be helpful for the management of patients, but when sustained unbearable stress is experienced, this may affect physical and mental health and result in burnout.24,25) Burnout, a symptom caused by continued stress, is a result of emotional pressure developed by long-term repeated exposure to continuous occupational stress.26) According to Maslach et al.,12) burnout can be divided into emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment, and can be measured by the MBI scale.

In this study, we found that subjects who experienced high degrees of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization reported more medical errors. This result was partially consistent with a study conducted by West et al.21) that found higher degrees of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and lower feelings of personal accomplishment were associated with a higher frequency of medical errors.27) In a study of internal medicine physicians at the Mayo, West et al.21) found that burnout was related to self-reported medical errors, independent of fatigue. In particular, when controlling for daytime sleepiness, severe emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were associated with higher rates of medical errors. When controlling for fatigue, severe emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and a lower sense of personal accomplishment were also associated with medical errors. In this study, the results of univariate analysis suggest that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are associated with medical errors. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for daytime sleepiness, only emotional exhaustion was significantly related with medical errors and depersonalization was associated with daytime sleepiness. Depersonalization is defined as a state in which patients are regarded as cases rather than as people and physicians may come to develop a negative or sarcastic attitude toward patients or their care-givers and become uncooperative.12) Because residents go without sleep for long periods during their training, they often feel sleepy in the daytime in spite of sufficient sleep at night. As a result, it is thought that residents often lose motivation for their work and come to have passive attitudes toward their patients. When controlling for fatigue, a higher degree of depersonalization was associated with significantly more medical errors. It is thought that if someone is tired and his/her energy is depleted, mental and physical resources are also reduced, finally leading to emotional exhaustion. Comparing this study with the study by West et al.21) there were some statistically significant differences with respect to the sub-areas of burnout, but these differences were due to the longer duration of their study period (from 2003 to 2008, with three month intervals) and larger number of subjects (430 residents of internal medicine). Maslach et al.12) defined burnout as over 27 points for emotional exhaustion or over 10 points for depersonalization, and emphasized that the three areas of burnout should be considered separately because they represent different aspects of this condition.13) Therefore, this study suggests that burnout is associated with self-reported medical errors regardless of fatigue and daytime sleepiness.

The study by West et al.21) indicated that burnout, as well as fatigue, must be addressed in the discussion of the improvement of medical training courses in the US.27) Similarly, it may be beneficial when planning medical training courses in Korea, to recognize a need to develope a strategy to alleviate burnout because burnout negatively affects the quality of medical service. Furthermore, like the study by Gopal et al.17) reporting that when resident working hours were reduced, the degree of burnout decreased, more studies that affect burnout are needed.

There are several limitations to this study. First, although the purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between burnout and medical errors, it was difficult to identify a causal relationship because medical errors were reported for the previous three months and burnout was assessed at the time of the survey. Because of this issue, results are best interpreted as associations rather than as definitive evidence of causation. Second, because medical errors were evaluated via self-report, it did not directly reflect clinically documented medical errors and could be arbitrary. Third, severity of medical errors was not considered. It was impossible to judge precisely if self-reported medical errors resulted in actual harm to patients. However, it is necessary to recognize that self-reported medical errors may be more likely to represent preventable medical errors. The fourth is the fact that the response rate was only 58.5%, and an analysis of characteristics of the non-respondents was not carried out. Fifth, because this study was performed at a university hospital in Busan, results may not be applicable to all medical residents. In the future, larger sample sizes may be necessary to better generalize this association. However, considering the fact that Korean studies of medical errors of residents are lacking, this study is an important step in identifying the relationship between resident burnout and self-reported medical errors in spite of its limitations.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS Institute of Medicine (US); Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1838–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barger LK, Ayas NT, Cade BE, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, et al. Impact of extended-duration shifts on medical errors, adverse events, and attentional failures. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockley SW, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP, et al. Effects of health care provider work hours and sleep deprivation on safety and performance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(11 Suppl):7–18. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum Behav. 1976;5:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–381. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudex C, Dolan P, Kind P, Williams A. Health state valuations from the general public using the visual analogue scale. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:521–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00439226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Novotny P, Johnson ME, Zhao X, Steensma DP, Lacy MQ, et al. The well-being and personal wellness promotion strategies of medical oncologists in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. Oncology. 2005;68:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000084519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, Frost MH, Bostwick JM, Atherton PJ, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:635–642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi HY. A study on affecting factors of social workers burnout [master's thesis] Seoul: Yonsei University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292:2880–2889. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, Prochazka AV. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2595–2600. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006;81:82–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, 3rd, Hahn SR, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JW, Jr, Noel PH, Cordes JA, Ramirez G, Pignone M. Is this patient clinically depressed? JAMA. 2002;287:1160–1170. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claus KE. The nature of stress. In: Claus KE, Bailey JT, editors. Living with stress and promoting well-being: a handbook for nurses. St. Louis: Mosby; 1980. pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freudenberger HJ. Burn-out: the organizational menace. Train Dev J. 1977;31:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pines AM, Kanner AD. Nurses' burnout: lack of positive conditions and presence of negative conditions as two independent sources of stress. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1982;20:30–35. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19820801-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:327–353. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302:1294–1300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]