Abstract

Bordetella pertussis is the causative agent of whooping cough, a potentially lethal respiratory disease in children. In immunocompetent individuals, B. pertussis infection elicits an effective adaptive immune response driven by activated CD4+ T cells. However, live B. pertussis persists in the host for 3 to 4 weeks prior to clearance. Thus, B. pertussis appears to have evolved short-term mechanisms for immune system evasion. We investigated the effects of B. pertussis wild-type strain BP338 on antigen presentation in primary human monocytes. BP338 infection reduced cell surface expression of HLA-DR and CD86 but not that of major histocompatibility complex class I proteins. This change in cell surface HLA-DR expression reflected intracellular redistribution of HLA-DR. The proportion of peptide-loaded molecules was unchanged in infected cells, suggesting that intracellular retention occurred after peptide loading. Although B. pertussis infection of monocytes induced rapid and robust expression of interleukin-10 (IL-10), HLA-DR redistribution did not appear to be explained by increased IL-10 levels. BP338-infected monocytes exhibited reduced synthesis of HLA-DR dimers. Interestingly, those HLA-DR proteins that were generated appeared to be longer-lived than HLA-DR in uninfected monocytes. BP338 infection also prevented gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induction of HLA-DR protein synthesis. Using mutant strains of B. pertussis, we found that reduction in HLA-DR surface expression was due in part to the presence of pertussis toxin whereas the inhibition of IFN-γ induction of HLA-DR could not be linked to any of the virulence factors tested. These data demonstrate that B. pertussis utilizes several mechanisms to modulate HLA-DR expression.

Bordetella pertussis is the gram-negative coccobacillus responsible for whooping cough, a disease that affects 20- to 40-million people worldwide each year and causes some 200,000 to 400,000 fatalities (World Health Organization [http://www.who.int]). It is transmitted via inhalation and causes respiratory epithelial cell dysfunction by adhering to cilia and secreting various toxins. In addition to affecting epithelial cells, B. pertussis has been found within pulmonary alveolar macrophages isolated from children coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (11) and may persist within leukocytes and epithelial cells (24, 30). B. pertussis is internalized by macrophages via adherence to the CR3 integrin, and its uptake and intracellular survival are dependent upon the presence of at least three virulence factors, filamentous hemagglutinin, adenylate cyclase, and pertussis toxin (24, 38, 53, 57). The results of experiments with mouse infection models using Bordetella bronchiseptica, a respiratory pathogen of animals, demonstrate that intracellular organisms localize to phagolysosomal compartments (28). The ability of B. pertussis to infect and survive within antigen-presenting cells (APCs) suggests that it might be capable of altering the host immune response by modifying APC function.

Evidence from human and mouse studies indicates that control of B. pertussis infection is associated with a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-restricted, Th1-type immune response (16, 49, 55). However, the ability to recover viable B. pertussis from hosts from 14 days up to several weeks following infection (34, 52) suggests that B. pertussis evades detection by the human immune system during early stages of host encounter. Previously, Boschwitz et al. assessed the ability of B. pertussis to modify CD4+ T-lymphocyte proliferation in response to monocyte presentation of tetanus toxoid. Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells failed to proliferate as well in the presence of B. pertussis-infected monocytes as they did in the presence of uninfected cells (9). In addition, Boldrick et al. have profiled gene expression in total peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) infected with B. pertussis in vitro and have found down-regulation of genes involved in antigen processing and presentation (8). These genes include those that encode MHC class II molecules, the antigen presentation cofactor HLA-DM, the lysosomal protease cathepsin B, and the lysosomal thiol reductase IP-30 (8). Interestingly, these genes were also down-regulated by chemical activators of immune cells (phorbol myristate acetate plus ionomycin), raising the possibility that these changes reflect general host responses to activating stimuli. In these two studies, the consequences of B. pertussis infection were analyzed with mixtures of human cells. The results in both experimental systems raised the possibility that B. pertussis has direct effects on monocytes, the most abundant APC type in the blood.

To investigate this possibility, we used highly purified monocytes and examined the ability of BP338, a wild-type laboratory strain, to modulate the class II antigen presentation pathway. We found that both trafficking and biosynthesis of constitutively expressed HLA-DR molecules are modulated by this organism. In addition, BP338 prevents gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induction of HLA-DR. Evidence from mutant B. pertussis strains implicates specific toxins in the effects on constitutively expressed class II molecules, while the effect on inducible class II expression is attributable to a B. pertussis component expressed by all mutant strains tested. We also observed rapid and potent stimulation of interleukin-10 (IL-10) production by BP338-infected monocytes. Thus, strain BP338 influences monocyte function pleiotropically in part through the action of distinct bacterial components.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

All strains of B. pertussis were grown at 37°C on Bordet-Gengou agar plates supplemented with sterile, whole, defibrinated sheep blood (Quad Five, Ryegate, Mont.) (9). Bacteria were inoculated onto plates 3 to 4 days prior to infection of monocytes. Within 3 h prior to monocyte infection, bacteria were resuspended in 10 ml of serum-free RPMI 1640 and the bacterial titer was estimated by measuring the optical density of a 10-fold dilution at 600 nm. The stock B. pertussis suspension was serially diluted onto blood agar plates for accurate quantitation of the multiplicity of infection (MOI). Aseptic purified pertussis toxin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). For details on B. pertussis strains, see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

B. pertussis strains

| Strain | Genotype and/or phenotype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| BP338 | Laboratory Tohoma I derivative wild-type strain | 54 |

| BP537 | BP338 derivative; contains a frameshift mutation in bvgS resulting in avirulent phage (Bvg−) and deficient expression of multiple proteins, including filamentous hemagglutinin, adenylate cyclase, and pertussis toxin | 54 |

| BPA2-6 | BP338 derivative; contains an amino acid substitution in CyaA adenylate cyclase catalytic site (K58M) resulting in loss of enzymatic activity | 9, 26 |

| BPTOX-6 | BP338 derivative; lacks the pertussis toxin operon | 54 |

| BP3586 | Filamentous hemagglutinin structural gene deleted in frame, leaving eight residues in the predicted protein product | 9 |

Monocyte isolation and infection.

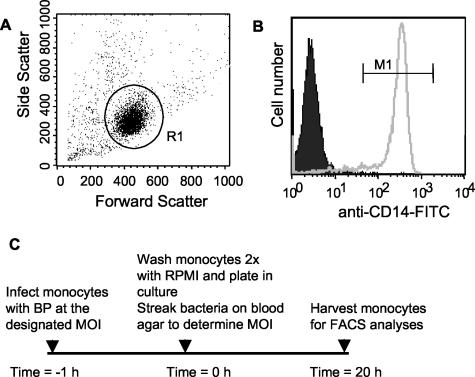

Approval for collection and use of clinical specimens was granted by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board for Medical Use of Human Subjects. PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation from whole-blood buffy coats obtained from healthy donors (Stanford Blood Bank). Cells were resuspended and incubated overnight in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-10% human serum-0.5% bovine serum albumin-2 mM EDTA, and monocytes from PBMCs were harvested using a negative-selection monocyte isolation method (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow-cytometric analyses of purified cells were performed to evaluate monocyte purity. A representative example is shown in Fig. 1. Forward- versus side-scatter analysis showed that 81% of cells were in the monocyte gate (Fig. 1A) and that of these, 94% were monocytes (as determined on the basis of CD14 surface marker antibody staining) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of monocyte purity and experimental protocol. The purity of the cells obtained using a Milteny Biotec monocyte isolation kit was assessed by flow cytometry. (A) Forward- versus side-scatter analysis. Monocytes (gate = R1) constituted 81% of the total purified cells, as shown by forward- versus side-scatter analysis. (B) Representative staining of gated, purified (gate = R1) cells with anti-CD14-FITC (open histogram) or an isotype control (shaded histogram). (C) Monocyte treatment protocol.

Unless otherwise stated, monocytes were infected with B. pertussis on a rotator at an average MOI of 30 for 1 h at room temperature in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Although other MOIs were investigated, the effects of infection were not directly proportional to the MOI (data not shown). Monocytes were washed two times with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum to remove excess bacteria. Monocytes were then plated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% human serum at a density of 106 cells/ml and incubated at 37°C. Assays were performed up to 20 h later (see Fig. 1C for a schematic representation of the monocyte treatment protocols used in this study). Aliquots of intact, infected monocytes were plated on blood agar plates immediately following the postinfection wash and at the 20-h time point. For all strains, the MOI remained below 0.1 throughout the 20-h period and no substantial bacterial growth in culture was observed (data not shown). To confirm that the effects observed throughout these studies did not reflect B. pertussis-mediated cytotoxicity, the viability of infected monocytes was determined by assessing the number of propidium iodide-positive (dead) cells as a percentage of the total cell number at 20 h postinfection. Cell death was minimal in both infected and uninfected cultures over the 20-h culture period (viability over multiple experiments, 88 to 100%), and the maximal difference in levels of cell death observed between infected and uninfected cell preparations was 10% (data not shown).

Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface molecule expression.

Monocytes were resuspended in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin, 10% human serum, and 0.1% sodium azide. Cells were stained with fluorescently tagged antibodies to MHC class II (clone TÜ36), MHC class I (clone TÜ149), and CD86 (clone BU63) (all at 1:20 dilution). Respective isotype controls were included in all experiments. All directly conjugated antibodies were purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). Cells were costained with 2 μg of propidium iodide/ml to detect dead cells. Log-integrated fluorescence of cells was determined using a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer after gating on CD14+ (monocytes)-propidium iodide-negative cells.

Western analysis of total HLA-DR protein levels.

Cells were removed from culture dishes with 1× PBS-0.5 mM EDTA, centrifuged at 500 × g, and lysed at 4°C for 1 h in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40 supplemented with protease inhibitors [100 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride {PMSF}/ml, 1 μg of aprotinin/ml]). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,500 × g for 5 min. Protein was quantitated using a protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) and bovine serum albumin standards according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total cellular proteins (20 μg) were resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). Membranes were immunoblotted with DA6.147, an anti-human HLA-DRα antibody that preferentially recognizes monomeric HLA-DR (27, 63) (1:250 dilution), or with anti-β-actin (1:5,000 dilution) (Sigma). Goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody was obtained from Caltag. Protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence detection (NEN Renaissance; NEN Life Science Products). Bands were quantitated by densitometry using National Institutes of Health Image software.

Total HLA-DR levels and intracellular localization.

At 20 h postinfection, uninfected or strain BP338-infected cells were stained at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated, anti-MHC class II antibody, washed twice, permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.), and restained with either FITC-conjugated anti-class II antibody (to measure total cell levels) or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated, anti-class II antibody (to measure intracellular HLA-DR levels). All cells were then fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Differences between infected and uninfected cells in levels of intracellular and extracellular HLA-DR were determined by flow cytometry as described above. To determine the effects of the presence of chloroquine on total cellular HLA-DR levels, uninfected, B. pertussis-infected, or IL-10 (10 ng/ml)-treated monocytes were grown in cultures for 20 h in the presence or absence of 25 μM chloroquine following 1 h of bacterial infection. Cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody, permeabilized, and restained with the same antibody.

SDS stability assay.

Monocytes were harvested at 24 h postinfection and incubated for 1 h in lysis buffer. Whole-cell lysates of Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells that are negative for HLA-DM (9.5.3 cells) (41, 43) or HLA-DRα chain (9.22.3 cells) (37) and the corresponding wild-type cells (8.1.6 cells) (41, 43) were used as controls. Two aliquots of total cellular protein, one of which was boiled for 10 min at 100°C to dissociate all HLA-DR dimers and one of which was not boiled, were prepared for each cell line (10 to 15 μg per aliquot of Epstein-Barr virus B-cell lysates and 25 to 50 μg per aliquot of monocyte lysates). Samples were resolved on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel under nonreducing conditions and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. DA6.147 antibody was used at a 1:500 dilution to detect HLA-DR.

HLA-DR synthesis and degradation. Analysis of HLA-DR and MHC class I synthesis.

Mock-infected or B. pertussis-infected monocytes were starved for 2 h in 10 ml of methionine-cysteine-free RPMI 1640 (Cellgro; Mediatech, Herndon, Va.) containing 5% dialyzed fetal bovine serum starting at 4, 9, and 23 h after B. pertussis infection and were then pulsed with 100 to 125 μCi of 35S protein labeling mix (Perkin Elmer, Boston, Mass.)/ml for 10 min. HLA-DR was immunoprecipitated (using ISCR3 antibody) from cell lysates, and MHC class I was immunoprecipitated using W6.32 antibody (the class I dimer-specific antibody) (1).

Analysis of HLA-DR degradation.

Monocytes were starved for 2 h at 20 h postinfection as described above and then pulsed for 4 h with 100 to 125 μCi 35S protein labeling mix/ml. For chase procedures, labeled cells were washed with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and resuspended in 20 ml of complete medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% human serum and 1 mM unlabeled methionine) and incubated at 37°C for 24 and 48 h (chase). L243 antibody (51) was used to immunoprecipitate HLA-DR from cell lysates at 0, 24, and 48 h postlabeling.

To obtain cell lysates, cells were washed once with 1× PBS containing 0.5 mM PMSF and labeled cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1% NP-40), rotated for 30 min at 4°C, and centrifuged at 12,500 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Lysates were precleared with rotation at 4°C overnight with 5 μl of normal rabbit serum and 30 μl of protein A-Sepharose. Lysates were normalized for counts per minute. Normalized counts represented equivalent protein loading results (as determined in separate Coomassie blue staining of gels) (data not shown). HLA-DR protein was immunoprecipitated with the HLA-DR-specific antibodies ISCR3 (47, 69) and L243. MHC class I proteins were precipitated with W6.32. The immunoprecipitated complexes were washed three times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5% NP-40) and boiled in SDS-sample buffer, and proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Labeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Detection of IL-10 production.

Strain BP338-infected monocytes were grown in cultures at a density of 106 cells/ml, and supernatants were collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h postinfection. For studies with bacterial mutants, BP338-, BP537-, BPA2-6-, BPTOX-6-, and BP3586-infected monocytes were grown in cultures at a density of 106 cells/ml and supernatants were collected at 24 h postinfection. MOIs were determined from the number of bacterial colonies generated by the plating of resuspended bacteria immediately prior to infection. IL-10 levels in cell supernatants were determined by using a Quantikine IL-10 kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Significant differences among infected samples were demonstrated by one-way analysis of variance. The means of groups were compared by the post hoc test of Newman-Keuls. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 2.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

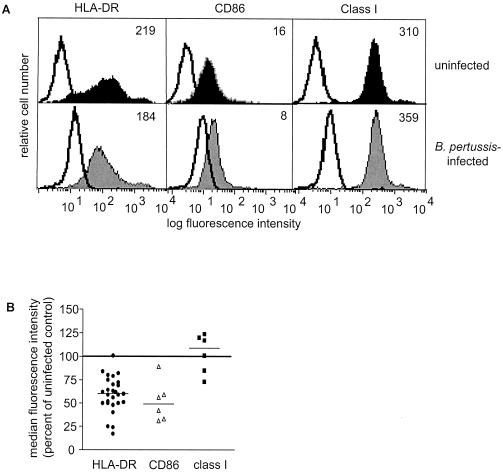

B. pertussis decreases cell surface expression of HLA-DR and CD86.

To examine the effects of BP338 on two cell surface proteins involved in antigen presentation (HLA-DR and MHC class I) and on the costimulatory molecule (CD86), we stained purified monocytes with the appropriate antibodies 20 h after infection and analyzed cell surface expression by flow cytometry. BP338 decreased constitutive cell surface HLA-DR and CD86 expression by an average of 29 and 48%, respectively, compared to the results seen with uninfected controls (Fig. 2). In contrast to the effects on HLA-DR, constitutive cell surface MHC class I levels were not altered by infection with BP338 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of B. pertussis on cell surface HLA-DR, CD86, and class I expression. (A) Cell surface expression of HLA-DR, CD86, and MHC class I on uninfected (top panels) and infected (bottom panels) monocytes. Shaded and closed histograms represent antigen-specific staining results. Open histograms represent the respective isotype controls. Numbers reflect median fluorescence intensity values of HLA-DR-FITC-, CD86-FITC-, or MHC class I-FITC-stained cells minus the median fluorescence intensity values of the respective isotype controls. (B) Summary scattergram of cell surface staining experiments. Symbols represent the percentages of cell surface expression in infected monocytes (individual symbols) compared to the results seen with uninfected cells (set at 100% and represented by the horizontal line) within each experiment, as calculated using median fluorescence intensity values. The mean percentage of expression of HLA-DR in infected cells compared to the results seen with uninfected controls was 71% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 64 and 78% [P < 0.001]). The mean percentage of expression of CD86 compared to the results seen with uninfected controls was 52% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 29 and 74% [P < 0.001]). The mean percentage of expression of MHC class I compared to the results seen with uninfected controls was 109% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 89 and 130% [P > 0.05]). The observed variability was not MOI dependent or donor dependent. Each experimental point represents monocytes harvested from at least two individuals.

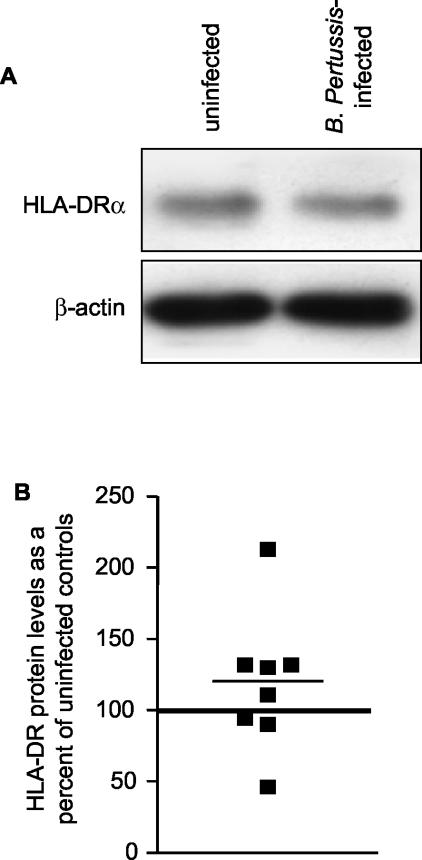

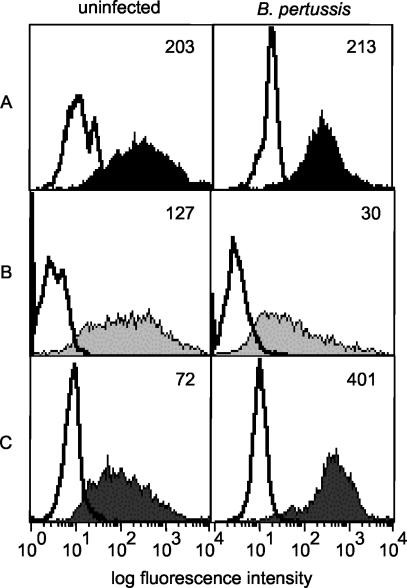

B. pertussis-infected monocytes contain higher levels of intracellular HLA-DR.

We next wanted to determine whether the decrease in HLA-DR cell surface expression reflected a decrease in total cellular HLA-DR. Immunoblot analysis of total protein extracts harvested from strain BP338-infected cells at 20 h most often showed levels of total cellular HLA-DR comparable to the results seen with extracts from uninfected cells (Fig. 3). As an alternative approach to the analysis of total HLA-DR levels/cell, monocytes were surface stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody, permeabilized, and then restained with either FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody (to assess total cellular HLA-DR levels) or with PE-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody (to measure intracellular levels). Uninfected and infected permeabilized cells stained only with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody exhibited equivalent levels of fluorescent staining, confirming that total cellular HLA-DR levels do not change upon infection with strain BP338 (Fig. 4A). As previously demonstrated, infected monocytes expressed lower amounts of cell surface HLA-DR than uninfected monocytes (Fig. 4B). In contrast, intracellular staining revealed higher levels of HLA-DR proteins in B. pertussis-infected cells than in uninfected cells (Fig. 4C). These data imply that exposure to B. pertussis results in redistribution of HLA-DR to intracellular compartments.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of total cellular HLA-DR protein levels in B. pertussis-infected monocytes. (A) Representative Western blot showing levels of expression of HLA-DR and β-actin in infected and uninfected monocytes. (B) Scattergram representation of densitometric analysis of HLA-DR protein levels normalized to β-actin levels. Individual symbols represent HLA-DR levels in infected monocytes and are shown as percentages of levels in uninfected cells within each experiment (represented by the horizontal line set at 100%). HLA-DR and β-actin band intensities were within the linear range of the densitometer gray scale. The mean percentage of expression of HLA-DR in infected monocytes compared to the results seen with uninfected monocytes was 119% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 78 and 159% [P > 0.05]).

FIG. 4.

Cellular redistribution of HLA-DR molecules in uninfected and B. pertussis-infected monocytes. (A) Total cellular HLA-DR. Uninfected and infected monocytes were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody, permeabilized, and restained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody. (B) Cell surface HLA-DR. Unpermeabilized uninfected and infected monocytes were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody. (C) Intracellular HLA-DR. Unpermeabilized monocytes were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody and then permeabilized and restained with PE-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody. Bottom panel histograms represent PE-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibody staining. For all panels, shaded and closed histograms represent HLA-DR-specific staining and open histograms represent isotype control staining. Unpermeabilized cells that were surface stained with HLA-DR-FITC and then restained with HLA-DR-PE did not exhibit significant levels of HLA-DR-PE staining (not shown). Numbers represent median fluorescence intensity levels. Data are representative of three independent experiments with comparable results.

B. pertussis blocks egress of peptide-loaded HLA-DR to the cell surface of monocytes.

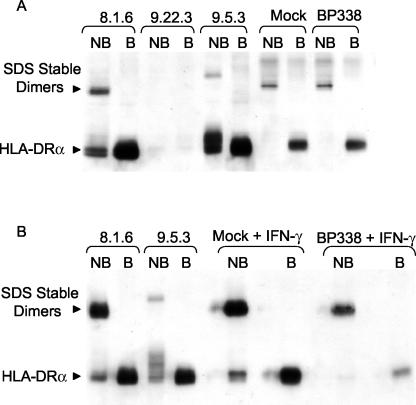

To determine the location of redistributed, intracellular HLA-DR molecules in BP338-infected monocytes, we used an assay that distinguishes mature, peptide-loaded HLA-DR molecules from immature HLA-DR molecules in human monocytes. In vitro peptide-loaded HLA-DR αβ dimers are stable at room temperature in SDS but dissociate into their monomeric subunits when boiled (25). In contrast, immature HLA-DR molecules dissociate in SDS without boiling (25). We assayed the SDS stability of HLA-DR molecules in whole-cell protein lysates from mock- and strain BP338-infected monocytes at 24 h postinfection. The majority of HLA-DR molecules in nonboiled lysates from both mock- and BP338-infected monocytes were SDS stable (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of B. pertussis effects on HLA-DR dimer formation. (A) HLA-DR dimers from nonboiled (NB) and boiled (B) protein samples harvested from 8.1.6 (wild-type), 9.22.3 (DRα-negative), and 9.5.3 (DM-negative) cells, mock-infected monocytes, and monocytes infected with B. pertussis for 24 h. (B) HLA-DR dimers from nonboiled and boiled protein samples harvested from 8.1.6, 9.5.3, and IFN-γ-stimulated mock-infected monocytes and B. pertussis-infected monocytes. The results are representative of five independent experiments, all showing that the majority of HLA-DR dimers in mock-treated and B. pertussis-treated monocytes are SDS stable.

To confirm that this result was not due to a technical limitation of our assay in detecting SDS-unstable HLA-DR molecules, we assayed HLA SDS stability in the HLA-DM null B lymphoblastoid 9.5.3 cell line and in its HLA-DM-expressing parental line, 8.1.6, according to established methods (6, 15, 41). HLA-DM facilitates peptide loading of HLA-DR in endosomal compartments (43, 59). As expected, unstable molecules were detected in nonboiled cell lysates from 9.5.3 cells and both SDS-stable and -unstable molecules were found in 8.1.6 cells. 9.22.3 cells, which lack DRα chains, were included as a control for the specificity of the anti-DR antibody. Furthermore, monomers were detected in lysates made from mock- and B. pertussis-infected monocytes treated with IFN-γ. Induction of HLA-DR synthesis by IFN-γ increased the levels of immature SDS-unstable HLA-DR molecules (Fig. 5B).

B. pertussis alters HLA-DR protein synthesis and degradation.

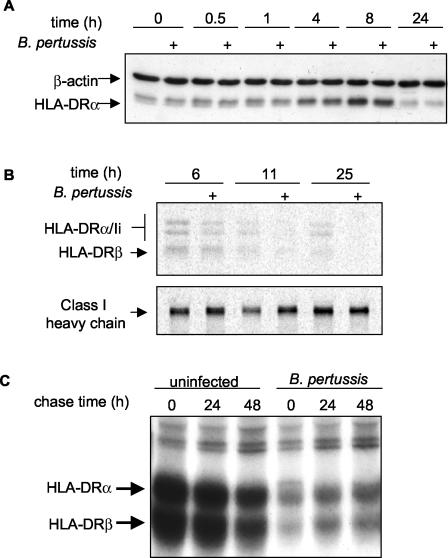

Over the 24-h culture period, constitutive levels of HLA-DR in monocytes initially rose over the first 8 h and then diminished by 20 to 24 h, returning to levels approximately equal to those seen initially (Fig. 6A). Metabolic labeling studies suggested that these changes were due to changing levels of HLA-DR synthesis. Synthesis was greater during the early hours (e.g., after 6 h) of culture than during the later hours (e.g., after 11 h) (Fig. 6B). To evaluate whether BP338 infection alters HLA-DR biosynthesis in culture-grown monocytes, we compared metabolically labeled HLA-DR proteins in infected and uninfected cultures. We found that synthesis of HLA-DR in infected monocytes was reduced as early as 6 h after 1 h of infection (Fig. 6B). In contrast, class I synthesis was unaffected by infection throughout the time course of the experiment (Fig. 6B). The modest BP338-associated decrease in HLA-DR biosynthesis was observed to be independent of the specific anti-HLA-DR monoclonal antibody used for immunoprecipitation. This suggests that nascent HLA-DR protein levels, and not the expression of a particular antibody epitope, were reduced. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation with polyclonal antisera that recognizes individual HLA-DR α and β chains indicated that synthesis, but not assembly, was reduced (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Effects of B. pertussis on HLA-DR steady-state levels, synthesis, and degradation. (A) Representative time course showing levels of expression of HLA-DR and β-actin in B. pertussis-infected (+) and uninfected monocytes. (B) Pulse-chase analysis of HLA-DR and MHC class I synthesis. Time values represent times after 1 h of B. pertussis infection. (C) Pulse-chase analysis of HLA-DR degradation. Time 0 represents HLA-DR levels at 24 h after 1 h of B. pertussis infection. Reductions in synthesis levels and increases in half-life were observed in two independent experiments.

The half-life of HLA-DR molecules synthesized after 24 h of culture growth was long (∼48 h), suggesting that rapid turnover did not contribute to the reduced steady-state levels at 24 h (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, pulse-chase analysis demonstrated that the half-life of nascent HLA-DR molecules was greater in infected cells (Fig. 6C). Thus, the long half-life of HLA-DR molecules in these cells may compensate for decreased synthesis, maintaining a consistent level of total HLA-DR protein in infected cells within the time frame of our experiments.

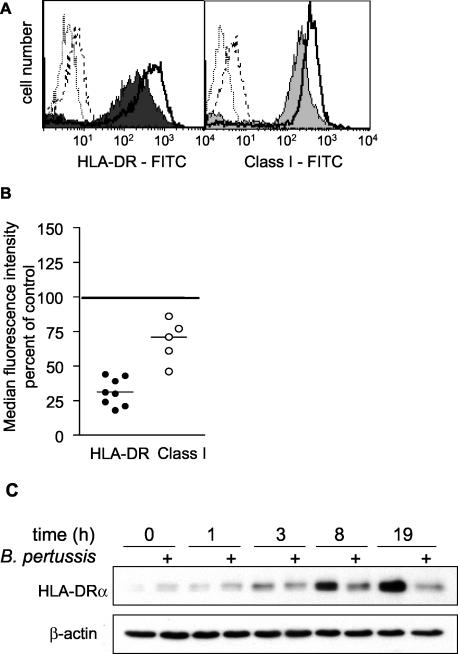

B. pertussis decreases IFN-γ-stimulated HLA-DR levels by preventing induction of HLA-DR protein synthesis.

IFN-γ is a Th1-type cytokine secreted by T cells, and possibly NK cells, during the immune response to B. pertussis infection (49). IFN-γ induces expression of CIITA, the master transcriptional regulator of expression of MHC class II and related molecules (such as HLA-DM and invariant chain) (7, 29, 33, 70). To determine whether strain BP338 infection impaired the ability of monocytes to modulate HLA-DR expression in response to IFN-γ, infected and uninfected cells were treated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml and surface HLA-DR levels was measured at 24 h (Fig. 7A). Monocytes infected with BP338 had reduced cell surface levels of HLA-DR (69% reduction) and MHC class I (32% reduction) compared to the results seen with uninfected cells (Fig. 7A and B). Western analysis of total cell lysates demonstrated that HLA-DR protein levels at 19 h were significantly reduced in infected, IFN-γ-stimulated monocytes (Fig. 7C). The substantial increase in HLA-DR levels by 8 h in IFN-γ-treated, uninfected cells, but not in infected cultures, argues that BP338 infection inhibits IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR synthesis in monocytes (Fig. 7C). This possibility was supported by the reduced levels of nascent HLA-DR dimers in infected cells, as measured according to levels of metabolic labeling after 20 h of IFN-γ treatment (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

B. pertussis effects on IFN-γ-stimulated HLA-DR expression. (A) Representative histogram of cell surface HLA-DR and MHC class I expression on uninfected or infected monocytes grown in cultures in the presence of 10 U of IFN-γ/ml. Shaded histograms represent antigen-specific staining of infected monocytes. Open histograms represent antigen-specific staining of uninfected monocytes. Dotted and dashed peaks represent isotype control staining on uninfected and infected monocytes, respectively. (B) Summary scattergram of cell surface staining experiments. Individual symbols represent the percentages of cell surface expression in infected monocytes compared to the results seen with IFN-γ-treated, uninfected cells within each experiment and were calculated using median fluorescence intensity values. Staining of IFN-γ-treated, uninfected cells was set at 100% and is represented by the horizontal line. The mean percentage of expression of HLA-DR in IFN-γ-stimulated infected monocytes compared to the results seen with IFN-γ-stimulated uninfected monocytes was 31% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 23 and 40% [P < 0.001]). The mean percentage of expression of MHC class I in IFN-γ-stimulated infected monocytes compared to the results seen with IFN-γ-stimulated uninfected monocytes was 68% (lower and upper confidence intervals, 49 and 87% [P < 0.001]). (C) Representative time course of total cellular HLA-DR in uninfected and B. pertussis-infected (+) monocytes grown in cultures in the presence of 10 U of IFN-γ/ml. Results from the time course were confirmed in two independent experiments, and the results seen at the latest time point (19 h) were confirmed in three additional experiments.

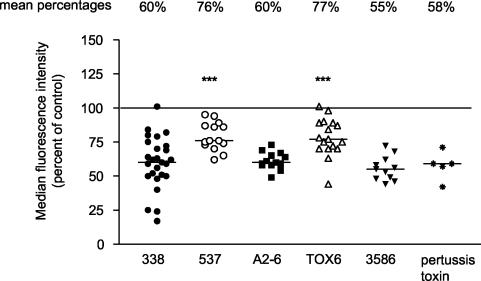

Pertussis toxin partially accounts for the decrease in HLA-DR cell surface expression.

B. pertussis expresses a number of virulence factors that cause localized damage at sites of infection as well as systemic disease. Among these factors, filamentous hemagglutinin and pertussis toxin facilitate attachment to host cells (66, 67) and the presence of pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin leads to increased host intracellular cyclic AMP levels (34, 45) and host cell dysfunction. To determine which specific virulence factors might be responsible for down-regulating cell surface HLA-DR expression, monocytes were infected for 1 h with strain BP338 or with mutant strain BPTOX-6, BPA2-6, BP3586, or BP537. We measured HLA-DR expression on cells by flow cytometry at 20 h postinfection. All mutants (with the exception of BP537, an avirulent phase variant, and BPTOX-6, a pertussis toxin operon deletion strain) decreased cell surface expression to the same extent as BP338 (Fig. 8). BP537 and BPTOX-6 decreased cell surface HLA-DR expression (relative to uninfected cells) but less so than the other B. pertussis strains. Treatment of cells with purified pertussis toxin decreased cell surface HLA-DR levels to nearly the same extent as seen with BP338. Differential effects of the mutant strains on cell surface HLA-DR expression were not attributable to differences in bacterial cell numbers, as determined by MOI measurements (data not shown). These results implicated pertussis toxin in the reduction of levels of HLA-DR at the monocyte cell surface but also suggested that other bacterial components contribute to the phenotype associated with B. pertussis infection.

FIG. 8.

Effects of B. pertussis mutant strains on cell surface HLA-DR levels. Cell surface HLA-DR levels at 20 h postinfection in monocytes infected with B. pertussis wild-type strain BP338 or mutant strain BPTOX-6, BPA2-6, BP3586, or BP537 are shown. Some monocytes were treated with 100 ng of purified pertussis toxin/ml. Individual symbols represent the median fluorescence intensity levels (as determined by flow cytometry) of infected monocytes and are displayed as percentages of the results seen with the uninfected control within each experiment (uninfected control = 100% [designated by the horizontal line]). Lower and upper confidence intervals for strains are as follows: BP338, 52 and 67%; BP537, 73 and 85%; BPA2-6, 57 and 65%; BPTOX-6, 71 and 85%; BP3586, 50 and 62%; pertussis toxin, 41 and 67%. Data are representative of at least five independent experiments. ***, significance (P < 0.001) with respect to the results seen with BP338 (wild-type strain of B. pertussis).

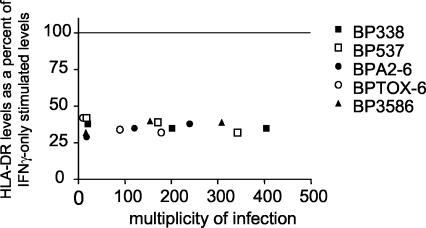

Inhibition of the IFN-γ response in infected monocytes.

To determine whether a specific virulence factor mediated the inhibition of inducible HLA-DR cell surface expression, we analyzed monocytes infected with wild-type or mutant B. pertussis strains and subsequently treated with 10 U of IFN-γ/ml for 20 h. Cell surface HLA-DR levels were measured by flow cytometry. We found that all mutants (including BP537, the avirulent phase strain) decreased cell surface HLA-DR expression to the same extent as the wild-type strain (Fig. 9). The findings suggested that the blockade of IFN-γ-stimulated HLA-DR expression at the cell surface is mediated by a component (such as lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) common to all strains or by some other component of the cell wall.

FIG. 9.

Effects of wild-type and mutant B. pertussis strains on IFN-γ-stimulated HLA-DR expression. Monocytes were infected for 1 h with strain BP338, BPTOX-6, BPA2-6, BP3586, or BP537 and then grown in cultures in the presence of IFN-γ for an additional 20 h. Individual symbols represent the median fluorescence intensity levels of infected monocytes stimulated with IFN-γ (the levels are presented as percentages of the values seen with the uninfected, IFN-γ-stimulated control within each experiment). In one experiment, cells were infected with various mutant MOIs.

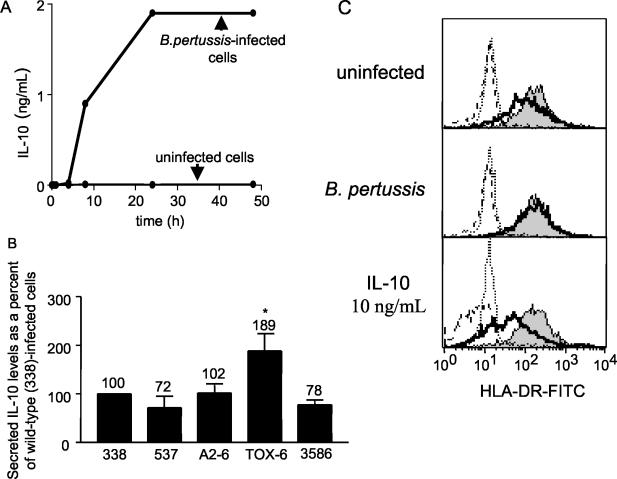

Reduced cell surface HLA-DR cannot be explained by IL-10 expression alone.

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-10 decreases MHC class II expression on various cell types and, in particular, that it drives MHC class II redistribution to intracellular compartments in monocytes (19, 35, 71). Infection of monocytes with strain BP338 stimulated secretion of IL-10 (which was detected as early as 8 h postinfection), with maximal, sustained levels achieved by 24 h (Fig. 10A). We did not detect IL-10 secretion in uninfected monocytes. Monocytes infected with BPTOX-6, the pertussis toxin mutant that had an impaired ability to decrease cell surface HLA-DR, stimulated the highest levels of IL-10 secretion (Fig. 10B), while monocytes infected with strains BP338, BP537, BPA2-6, and BP3586 secreted lower and equivalent levels of IL-10 (Fig. 10B). The lack of a correlation between the degree of HLA-DR down-regulation and the levels of IL-10 secretion induced by these mutant strains suggested that the effects of B. pertussis infection on MHC class II expression are not mediated by IL-10 alone.

FIG. 10.

IL-10 secretion from wild-type and mutant B. pertussis-infected monocytes. (A) Time course of secreted IL-10 levels from uninfected or strain BP338-infected monocytes. (B) Secreted IL-10 levels from BP338, BP537, BPA2-6, BPTOX-6, and BP3586-infected monocytes. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Numbers above error bars indicate levels of secreted IL-10 as percentages of the levels seen with BP338-infected cells (set at 100%). *, significance (P < 0.05) with respect to the results seen with the BP338 wild-type strain. (C) Total cellular levels of HLA-DR in BP338-infected monocytes in the presence and absence of chloroquine. Solid lines represent HLA-DR levels in the absence of chloroquine. Shaded histograms represent HLA-DR levels in chloroquine-treated cells. Dotted and dashed peaks represent the isotype controls for chloroquine-treated and non-chloroquine-treated cells, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments (all with comparable results).

In a second approach to the evaluation of IL-10 as a factor in strain BP338 alteration of HLA-DR expression, we used the indirect endosomal protease inhibitor chloroquine to compare constitutive HLA-DR levels in BP338-infected and IL-10-treated monocytes. Chloroquine raises endosomal pH levels and inhibits acid-active proteases, thus preventing endosomal HLA-DR degradation (23). In uninfected, chloroquine-treated monocytes, total cellular HLA-DR protein levels were 173% (range = 43 to 471%) (Fig. 10C, top panel) of those seen in non-chloroquine-treated cells (Fig. 10C, top panel). BP338-infected, chloroquine-treated monocytes did not exhibit increased total cellular HLA-DR levels relative to untreated, B. pertussis-infected monocytes (Fig. 10C, middle panel). In contrast, IL-10-treated monocytes had reduced total HLA-DR protein levels compared to the results seen with untreated, uninfected cells (Fig. 10C, top and bottom panels) and this reduction in HLA-DR levels was prevented by chloroquine. These data suggest that HLA-DR protein in BP338-infected cells is localized to compartments unaffected by chloroquine. This is in contrast to the effects of IL-10, which (at the dose studied) apparently reduces HLA-DR levels by inducing relocalization of HLA-DR to chloroquine-sensitive endosomal compartments.

DISCUSSION

Little is known about how B. pertussis modulates APC functions in humans. In this study, we found that strain BP338 decreased cell surface HLA-DR levels without altering total cellular levels. This implicated intracellular redistribution as the mechanism for decreased surface expression. Infected monocytes examined after 24 h exhibited decreased HLA-DR synthesis and degradation compared to the results seen with uninfected controls. These effects were specific to HLA-DR, as neither cell surface MHC class I protein levels nor synthesis was altered. Preliminary evidence from studies of purified monocytes corroborates previously published data from microarray-based studies of infected PBMCs; the data indicated reduced DRα and DRβ transcript levels following B. pertussis exposure (8). These data argue that reduced synthesis of HLA-DR protein reflects reduced transcript abundance. Pulse-chase analyses also demonstrated that the half-life of HLA-DR α and β chains was longer in BP338-infected monocytes (>48 h) than in uninfected monocytes (∼48 h). The comparable steady-state levels of HLA-DR that were observed in the presence and absence of BP338 infection (up to 48 h postinfection) appear to result from a compensatory effect of increased protein half-life in the face of decreased protein synthesis.

The bulk of total cellular HLA-DR in infected cells was SDS stable, which indicated that it was peptide loaded and mature. Assembly of newly synthesized HLA-DR α and β chains with invariant chain occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. After assembly, complexes are transported through the trans-Golgi network where they are modified with N-linked glycans. Following transport through the Golgi, HLA-DR-invariant complexes traffic to endosomal-lysosomal compartments where Ii is proteolytically degraded by pH-sensitive enzymes and exchanged for exogenous antigenic peptide in an HLA-DM-dependent manner (4, 10, 17, 32). HLA-DM further edits the peptides associated with class II molecules in favor of more stable peptide-class II complexes (59). These complexes are exported to the plasma membrane (65). Thus, the preservation of comparable levels of SDS-stable dimers in B. pertussis-infected cells argues that the cell surface changes reflect either reduced egress of peptide-loaded molecules to the cell surface or the internalization of cell surface, mature class II molecules. These two possible mechanisms differ from those employed by other human pathogens in altering cell surface MHC class II expression. For example, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef indirectly affects the efficiency of the sorting signals in the cytoplasmic tail of Ii (63), Epstein-Barr virus BZLF2 protein binds the HLA-DRβ chain on the cell surface without reducing overall surface class II levels (60), and Leishmania amazonensis both internalizes and degrades host cell class II molecules (18).

In this study, treatment of cells with the lysosomotropic agent chloroquine increased HLA-DR levels in uninfected cells to a greater extent than in B. pertussis-infected cells. This suggests that intracellular HLA-DR in infected cells is localized to less degradative compartments (i.e., recycling endosomes versus lysosomes) than the intracellular HLA-DR in uninfected cells. Alternatively, the intracellular compartments to which HLA-DR molecules are localized in uninfected and B. pertussis-infected cells may be the same; however, levels or activities of enzymes involved in lysosomal degradation may be altered. Lysosomal proteolysis requires protein denaturation and reduction of inter- and intrachain disulfide bonds (3). Cathepsin B, a lysosomal cysteine protease (44), and the lysosomal reductase IP-30 have been implicated in this process (2, 3). DNA microarray analyses demonstrated that B. pertussis decreases both cathepsin B and IP-30 gene transcripts (8).

B. pertussis produces several virulence factors that enable the pathogen to enter the host and interact with specific target tissues, proliferate, and develop localized and systemic damage and that potentially help it to evade the host immune response (34). Pathogenicity is multifactorial and is thought to reflect a composite effect of a group of virulence factors (34). In the present study, we examined the effect of mutants lacking adenylate cyclase toxin, pertussis toxin, or filamentous hemagglutinin on HLA-DR expression. Pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin are typically used in combination in various acellular pertussis vaccines and have been shown to play critical roles in facilitating B. pertussis attachment to cells (14, 31, 57, 66). Adenylate cyclase toxin contributes to the survival of B. pertussis within human macrophages and generates supraphysiologic levels of cyclic AMP, a molecule that has been reported to elicit various effects on intracellular signaling events (38, 48, 64, 68). In this study, we demonstrated that pertussis toxin is partially responsible for decreased cell surface HLA-DR levels, as a mutant lacking the toxin had an impaired ability to decrease cell surface levels. Similar results were observed for an avirulent mutant strain lacking all three proteins as well as other Bvg-regulated factors. In addition, pertussis toxin alone was sufficient for suppression of HLA-DR surface expression. Interestingly, the pertussis toxin mutant and the avirulent mutant caused a partial reduction in HLA-DR surface expression. Taken together, these data suggest that pertussis toxin acts in concert with another B. pertussis component (perhaps LPS) in modulating HLA-DR expression; this possibility will be addressed in future studies.

LPS induces IL-10 synthesis in, and secretion from, monocytes (12). IL-10 is a Th2 cytokine that decreases MHC class II expression on various cell types (19, 34, 71). In this study, strain BPTOX-6 (the pertussis toxin mutant) produced the highest levels of secreted IL-10 and yet elicited the weakest response with regard to a decrease in constitutive cell surface HLA-DR levels. The high levels of IL-10 secreted by monocytes infected with the pertussis toxin mutant are consistent with previous findings showing that pertussis toxin inhibits IL-10 production and that filamentous hemagglutinin induces IL-10 production (5, 40, 42). Also, in contrast to BP338 infection, IL-10 treatment of monocytes appeared to decrease total cellular HLA-DR levels, at least in part, by increasing degradation. Although IL-10 has been shown to inhibit upregulation of costimulatory molecules on macrophages (20), the data presented here argue that IL-10 is not the principal factor responsible for the observed effects of B. pertussis infection on constitutive cell surface HLA-DR expression.

In similarity to its effects on constitutive HLA-DR expression, BP338 infection prevented IFN-γ-induced HLA-DR expression. IFN-γ induction of HLA-DR by the Jak1/Jak2-Stat1 signaling cascade is well documented (36, 46, 50, 56). Furthermore, IL-10 activation of Stat3 and the subsequent induction of the Stat1 phosphorylation inhibitors SOCS1 and SOCS3 have also been confirmed (21, 22, 58, 61). Preliminary studies on BP338 infection of monocytes demonstrate an increase in SOCS1 and SOCS3 expression as well as a decrease in Stat1 phosphorylation (J. Shumilla, data not shown), suggesting that BP338 induction of IL-10 might be responsible for inhibition of IFN-γ induction of HLA-DR. It will be of interest to examine the ability of B. pertussis LPS to block IFN induction of HLA-DR.

Reduction of HLA-DR synthesis, prolongation of the half-life of HLA-DR molecules, and resistance to IFN-γ induction of new HLA-DR synthesis are changes that overlap with activation-maturation profiles of monocytes (8) and dendritic cells (13) and have been observed as responses to the presence of LPS (8, 13). These changes likely allow the host APC to capture B. pertussis antigenic determinants and facilitate their presentation by reducing HLA-DR/peptide complex turnover. On the other hand, pertussis toxin-induced sequestration of peptide/MHC complexes may facilitate escape from T-cell recognition and activation. Further, robust expression of IL-10 (stimulated by filamentous hemagglutinin) and reduction of CD86 levels are likely to favor induction of immunosuppressive or regulatory phenotypes in those B. pertussis-reactive T cells that do respond (39). Animal models of B. pertussis infection may provide further clues concerning the relative benefits to host and pathogen of the pleiotropic B. pertussis effects on APCs.

Acknowledgments

J. A. Shumilla was supported by an American Lung Association fellowship and a Stanford University School of Medicine Dean's postdoctoral award. T. M. C. Hornell was supported by the Cancer Research Institute. J. Huang was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S. Narasimhan was supported by the Center for Clinical Immunology at Stanford. This work was also supported by grants from the Lucille Packard Foundation for Children's Health and the NIH (E.D.M. and D.A.R.).

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Accola, R. S. 1983. Human B cell variants immunoselected against a single Ia antigen subset have lost expression of several Ia antigen subsets. J. Exp. Med. 157:1053-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arunachalam, B., M. Pan, and P. Cresswell. 1998. Intracellular formation and cell surface expression of a complex of an intact lysosomal protein and MHC class II molecules. J. Immunol. 160:5797-5806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arunachalam, B., U. T. Phan, H. J. Geuze, and P. Cresswell. 2000. Enzymatic reduction of disulfide bonds in lysosomes: Characterization of a gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:745-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakke, O., and T. W. Nordeng. 1999. Intracellular traffic to compartments for MHC class II peptide loading: signals for endosomal and polarized sorting. Immunol. Rev. 172:171-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barcova, M., C. Speth, L. Kacani, F. Ubrall, H. Stoiber, and M. P. Dierich. 1999. Involvement of adenylate cyclase and p70S6-kinase activation in IL-10 up-regulation in human monocytes by gp41 envelope protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Pflueg. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 437:538-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billing, R. J., M. Safani, and P. Peterson. 1976. Isolation and characterization of human B cell alloantigens. J. Immunol. 117:1589-1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanar, M. A., E. C. Boettger, and R. A. Flavell. 1988. Transcriptional activation of HLA-DRα by interferon γ requires a trans-acting protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:4672-4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldrick, J., A. A. Alizadeh, M. Diehn, S. Dudoit, C. L. Liu, C. E. Belcher, D. Botstein, L. M. Staudt, P. O. Brown, and D. A. Relman. 2002. Stereotyped and specific gene expression programs in human innate immune responses to bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:972-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boschwitz, J. S., J. W. Batanghari, H. Kedem, and D. A. Relman. 1997. Bordetella pertussis infection of human monocytes inhibits antigen-dependent CD4 T cell proliferation. J. Infect. Dis. 176:678-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brachet, V., G. Raposo, S. Amigorena, and I. Mellman. 1997. Ii chain controls the transport of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules to and from lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 137:51-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bromberg, K. G. Tannis, and P. Steiner. 1991. Detection of Bordetella pertussis associated with alveolar macrophages of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Infect. Immun. 59:4715-4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne, A., and D. J. Reen. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide induces rapid production of IL-10 by monocytes in the presence of apoptotic neutrophils. J. Immunol. 168:1968-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella, M., A. Engering, V. Pinet, J. Pieters, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1997. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature 388:782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherry, J. D. 1997. Comparative efficacy of acellular pertussis vaccines: an analysis of recent trials. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:S90-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cresswell, P. 1977. Human B cells alloantigens; separation from other membrane molecules by affinity chromatography. Eur. J. Immunol. 7:636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Magistris, M. T., M. Romano, S. Nuti, R. Rappuoli, and A. Tagliabue. 1988. Dissecting human T cell responses against Bordetella species. J. Exp. Med. 168:1351-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denzin, L. K., C. Hammond, and P. Cresswell. 1996. HLA-DM interactions with intermediates in HLA-DR maturation and a role for HLA-DM in stabilizing empty HLA-DR molecules. J. Exp. Med. 184:2153-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Souza Leao, S., T. Lang, E. Prina, R. Hellio, and J.-C. Antione. 1995. Intracellular Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes internalize and degrade MHC class II molecules of their host cells. J. Cell Sci. 108:3219-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wall Malefyt, R., J. Haanen, H. Spits, M.-G. Roncarolo, A. teVelde, C. Figdor, K. Johnson, R. Kastelein, H. Yssel, and J. E. de Vries. 1991. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J. Exp. Med. 174:915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding, L., P. S. Linsley, L.-Y. Huang, R. N. Germain, and E. M. Shevach. 1993. IL-10 inhibits macrophage costimulatory activity by selectively inhibiting the up-regulation of B7 expression. J. Immunol. 151:1224-1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endo, T. A., M. Masuhara, M. Yokouchi, R. Suzuki, H. Sakamoto, K. Mitsui, A. Matsumoto, S. Tanimura, M. Ohtsubo, H. Misawa, T. Miyazaki, N. Leonor, T. Taniguchi, T. Fujita, Y. Kanakura, S. Komiya, and A. Yoshimura. 1997. A new protein containing an SH2 domain that inhibits JAK kinases. Nature 387:921-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finbloom, D. S., and K. D. Winestock. 1995. IL-10 induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of tyk2 and Jak1 and the differential assembly of STAT1α and STAT3 complexes in human T cells and monocytes. J. Immunol. 155:1079-1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox, R. I., and H. I. Kang. 1993. Mechanism of action of antimalarial drugs: inhibition of antigen processing and presentation. Lupus 2:S9-S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman, R. L., K. Nordensson, L. Wilson, E. T. Akporiaye, and D. E. Yocum. 1992. Uptake and intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 60:4578-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Germain, R. N., and L. R. Hendrix. 1991. MHC class II structure, occupancy and surface expression determined by post-endoplasmic reticulum antigen binding. Nature 353:134-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross, M. K., D. C. Au, A. L. Smith, and D. R. Storm. 1992. Targeted mutations that ablate either the adenylate cyclase or hemolysin function of the bifunctional cyaA toxin of Bordetella pertussis abolish virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4898-4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guy, K., V. Van Heyningen, B. B. Cohen, D. L. Deane, and C. M. Steel. 1982. Differential expression and serologically distinct subpopulations of human Ia antigens detected with monoclonal antibodies to Ia alpha and beta chains. Eur. J. Immunol. 12:942-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guzman, C. A., M. Rhode, M. Bock, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Invasion and intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 62:5528-5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han, Y., Z.-H. L. Zou, and R. M. Ransohoff. 1999. TNF-α suppresses IFN-γ-induced MHC class II expression in HT1080 cells by destabilizing class II trans-activator mRNA. J. Immunol. 163:1435-1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishibashi, Y., D. A. Relman, and A. Nishikawa. 2001. Invasion of human respiratory epithelial cells by Bordetella pertussis: possible role for a filamentous hemagglutinin Arg-Gly-Asp sequence and α5β1 integrin. Microb. Pathog. 30:279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishibashi, Y., S. Claus, and D. A. Relman. 1994. Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin interacts with a leukocyte signal transduction complex and stimulates bacterial adherence to monocyte CR3 (CD11b/CD18). J. Exp. Med. 180:1225-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang, S., L. Liang, C. D. Parker, and J. F. Collawn. 1998. Structural requirements for major histocompatibility complex class II invariant chain endocytosis and lysosomal targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20644-20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelley, V. E., W. Fiers, and T. B. Strom. 1984. Cloned human interferon-γ but not interferon-β or -α, induces expression of HLA-DR determinants by fetal monocytes and myeloid leukemic cell lines. J. Immunol. 132:240-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr, J. R., and R. C. Matthews. 2000. Bordetella pertussis infection: pathogenesis, diagnosis, management, and the role of protective immunity. Eur. J. Clin. Microb. Infect. Dis. 19:77-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koppelman, B., J. J. Neefjes, J. E. de Vries, and R. de Waal Malefyt. 1997. Interleukin-10 down-regulates MHC class II αβ peptide complexes at the plasma membrane of monocytes by affecting arrival and recycling. Immunity 7:861-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotenko, S. V., and S. Pestka. 2000. Jak-Stat signal transduction pathway through the eyes of cytokine class II receptor complexes. Oncogene 19:2557-2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobo, P. I., M. Y. Chang, and E. Mellins. 1996. Mechanisms by which HLA-class II molecules protect human B lymphoid tumour cells against NK- and LAK-mediated cytolysis. Immunology 88:625-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masure, H. R. 1993. The adenylate cyclase toxin contributes to the survival of Bordetella pertussis within human macrophages. Microb. Pathog. 14:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGuirk, P., C. McCann, and K. H. Mills. 2002. Pathogen-specific T regulatory cells induced in the respiratory tract by a bacterial molecule that stimulates interleukin 10 production by dendritic cells: a novel strategy for evasion of protective T helper type 1 responses by Bordetella pertussis. J. Exp. Med. 195:221-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGuirk, P., and K. H. G. Mills. 2000. Direct anti-inflammatory effect of a bacterial virulence factor: IL-10-dependent suppression of IL-12 production by filamentous hemagglutinin from Bordetella pertussis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellins, E., L. Smith, B. Arp, T. Cotner, E. Celis, and D. Pious. 1990. Defective processing and presentation of exogenous antigens in mutants with normal HLA class II genes. Nature 343:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mielcarek, N., E. H. Hornquist, B. R. Johansson, C. Locht, S. N. Abraham, and J. Holmgren. 2001. Interaction of Bordetella pertussis with mast cells, modulation of cytokine secretion by pertussis toxin. Cell. Microbiol. 3:181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris, P., J. Shaman, M. Attaya, M. Amaya, S. Goodman, C. Bertman, J. J. Monaco, and E. Mellins. 1994. An essential role for HLA-DM in antigen presentation by class II major histocompatibility molecules. Nature 368:551-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mort, J. S., and D. J. Buttle. 1997. Cathepsin B. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29:715-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouallem, M., Z. Farfel, and E. Hanski. 1990. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin: intoxication of host cells by bacterial invasion. Infect. Immun. 58:3759-3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muhlethaler-Mottet, A., W. Di Berardino, L. A. Otten, and B. Mach. 1998. Activation of the MHC class II transactivator CIITA by interferon-γ requires cooperative interaction between Stat1 and USF-1. Immunity 8:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogasawara, K., H. Kojima, H. Ikeda, N. Ishikawa, M. Kasahara, Y. Fukasawa, T. Natori, A. Wakisaka, Y. Kikuchi, and M. Aizawa. 1986. A study on class II antigens involved in the T cell proliferative responses to PPD using cross-reacting monoclonal antibodies in human and murine systems. Immunobiology 171:112-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearson, R. D., P. Symes, M. Conboy, A. A. Weiss, and E. L. Hewlett. 1987. Inhibition of monocyte oxidative responses by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J. Immunol. 139:2749-2754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peppoloni, S., L. Nencioni, A. D. Tommaso, A. Tagliabue, P. Parronchi, S. Romagnani, R. Rappuoli, and M. T. De Magistris. 1991. Lymphokine secretion and cytotoxic activity of human CD4+ T-cell clones against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 59:3768-3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piskurich, J. F., Y. Wang, M. W. Linhoff, L. C. White, and J. P. Y. Ting. 1998. Identification of distinct regions of 5′ flanking DNA that mediate constitutive, IFNγ, STAT1, and TGF-β-regulated expression of the class II transactivator gene. J. Immunol. 160:233-240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polakova, K., and M. Karpatova. 1990. Study of monomorphic determinants on DR molecules of HLA class II antigens. Neoplasma 37:239-251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Preston, N. W. 1986. Recognising whooping cough. Br. Med. J. 292:901-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Relman, D., E. Tuomanen, S. Falkow, D. T. Golenbock, K. Saukkonen, and S. D. Wright. 1990. Recognition of a bacterial adhesion by an integrin: macrophage CR3 (αMβ2, CD11b/CD18) binds filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Cell 61:1375-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Relman, D. A., M. Domenighini, E. Tuomanen, R. Rappuoli, and S. Falkow. 1989. Filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis: nucleotide sequence and crucial role in adherence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2637-2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan, M., G. Murphy, L. Gothefors, L. Nilsson, J. Storsaeter, and K. H. G. Mills. 1997. Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in children is associated with preferential activation of type 1 T helper cells. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1246-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakatsume, M., K. Igarashi, K. D. Winestock, G. Garotta, A. C. Larner, and D. S. Finbloom. 1995. The Jak kinases differentially associate with the α and β (accessory factor) chains of the interferon γ receptor to form a functional receptor unit capable of activating STAT transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17528-17534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saukkonen, K., C. Cabellos, M. Burroughs, S. Prasad, and E. Tuommanen. 1991. Integrin-mediated localization of Bordetella pertussis within macrophages: role in pulmonary colonization. J. Exp. Med. 173:1143-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen, X., F. Hong, V.-A. Nguyen, and B. Gao. 2000. IL-10 attenuates IFN-α-activated STAT1 in the liver: involvement of SOCS2 and SOCS3. FEBS Lett. 480:132-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sloan, V. S., P. Cameron, G. Porter, M. Gammon, M. Amaya, E. Mellins, and D. M. Zaller. 1995. Mediation by HLA-DM of dissociation of peptides from HLA-DR. Nature 375:802-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spriggs, M. K., R. J. Armitage, M. R. Comeau, L. Strockbine, T. Farrah, B. Macduff, D. Ulrich, M. R. Alderson, J. Mullberg, and J. I. Cohen. 1996. The extracellular domain of the Epstein-Barr virus BSLF2 protein binds the HLA-DR β chain and inhibits antigen presentation. J. Virol. 70:5557-5563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Starr, R., T. A. Willson, E. M. Viney, L. J. L. Murray, J. R. Rayner, B. J. Jenkins, T. J. Gonda, W. S. Alexander, D. Metcalf, N. A. Nicola, and D. J. Hilton. 1997. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signaling. Nature 387:917-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steel, C. M., V. Van Heyningen, K. Guy, B. B. Cohen, and D. L. Deane. 1982. Influence of monoclonal anti-Ia like antibodies on activation of human lymphocytes. Immunology 47:597-603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stumptner-Cuvelette, P., S. Morchoisne, M. Dugast, S. Le Gall, G. Raposo, O. Schwartz, and P. Benaroch. 2001. HIV-1 Nef impairs MHC class II antigen presentation and surface expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12144-12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamir, A., and N. Isakov. 1994. Cyclic AMP inhibits phosphatidylinositol-coupled and -uncoupled mitogenic signals in T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 152:3391-3399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thery, C., V. Brachet, A. Regnault, M. Rescigno, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, C. Bonnerot, and S. Amigorena. 1998. MHC class II transport from lysosomal compartments to the cell surface is determined by stable peptide binding, but not by the cytosolic domains of the α- and β-chains. J. Immunol. 161:2106-2113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuomanen, E., and A. Weiss. 1985. Characterization of two adhesions of Bordetella pertussis for human ciliated respiratory-epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 152:118-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van't Wout, J., W. N. Burnette, V. L. Mar, E. Rozdzinski, S. D. Wright, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1992. Role of carbohydrate recognition domains of pertussis toxin in adherence of Bordetella pertussis to human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 60:3303-3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walton, K. M., R. P. Rehfuss, J. C. Chrivia, J. E. Lochner, and R. H. Goodman. 1992. A dominant repressor of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP)-regulated enhancer-binding protein activity inhibits the cAMP-mediated induction of the somatostatin promoter in vivo. Mol. Endocrinol. 6:647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watanabe, M., T. Suzuki, M. Taniguchi, and N. Shinohara. 1983. Monoclonal anti-Ia murine alloantibodies crossreactive with the Ia-homologue of other mammalian species including humans. Transplantation 36:712-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiss, A. A., E. L. Hewlett, G. A. Myers, and S. Falkow. 1983. Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 42:33-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wright, K. L., K.-C. Chin, M. Linhoff, C. Skinner, J. A. Brown, J. M. Boss, G. R. Stark, and J. P. Y. Ting. 1998. CIITA stimulation of transcription factor binding to major histocompatibility complex class Ii and associated promoters in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6267-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yue, F. Y., R. Dummer, R. Geertsen, G. Hofbauer, E. Laine, S. Manolio, and G. Gurg. 1997. Interleukin-10 is a growth factor for human melanoma cells and down-regulates HLA class-I, HLA class-II and ICAM-1 molecules. Int. J. Cancer 71:630-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]