Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to determine whether volumetric contrast-enhanced ultrasound (US) imaging could detect early tumor response to anti–death receptor 5 antibody (TRA-8) therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy in a preclinical triple-negative breast cancer animal model.

Methods

Animal experiments had Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. Thirty breast tumor–bearing mice were administered Abraxane (paclitaxel; Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ), TRA-8, TRA-8 + Abraxane, or saline as a control on days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 17. Volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging was performed on days 0, 1, 3, and 7 before dosing. Changes in parametric maps of tumor perfusion were compared with the tumor volume and immunohistologic findings.

Results

Therapeutic efficacy was detected within 7 days after drug administration using parametric volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging. Decreased tumor perfusion was observed in both the TRA-8-alone– and TRA-8 + Abraxane–dosed animals compared to control tumors (P = .17; P = .001, respectively). The reduction in perfusion observed in the TRA-8 + Abraxane group was matched with a corresponding regression in tumor size over the same period. Survival curves illustrate that the combination of TRA-8 + Abraxane improves drug efficacy compared to the same drugs administered alone. Immunohistologic analysis revealed increased levels of apoptotic activity in the TRA-8-dosed tumors, confirming enhanced antitumor effects.

Conclusions

Preliminary results are encouraging, and volumetric contrast-enhanced US-based tumor perfusion imaging may prove clinically feasible for detecting and monitoring the early antitumor effects in response to combination TRA-8 + Abraxane therapy.

Keywords: antibody therapy, breast cancer, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, microbubbles, volumetric imaging

Breast cancer is the second most prevalent cancer type diagnosed in women and the second most frequent cause of cancer deaths in women. Typically, the more successful breast cancer treatments are targeted to cancer cell receptors known to facilitate tumor growth, namely, estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 proteins. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), however, is a particularly aggressive form of breast cancer that is devoid of the aforementioned receptors and less responsive to standardized treatment.1

Tumor cytotoxicity has been shown to be mediated by tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand and agonistic monoclonal antibodies through interactions with cell surface death receptors (DR5) with activation of the caspase-8 pathway.2–5 An agonistic monoclonal antibody (TRA-8) specific for human DR5 was developed and shown to induce apoptosis of breast cancer tumor cell lines.6 Additionally, TRA-8 in combination with chemotherapeutic agents has an antitumor effect that can yield a substantial regression of tumor size in TNBC murine models.7 Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging has also been shown to be useful in early detection of the response to TRA-8 therapy in animal models due to pronounced apoptosis and intratumoral changes in diffusion properties.8 A follow-up animal study using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging also proved capable of distinguishing the early response to TRA-8 therapy.9

The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (US) to assess tumor perfusion has been explored extensively in recent years. By tracking the time-intensity profile of backscattered echo signals, blood flow measurements can be estimated as presented in recent preclinical10–18 and clinical19– 24 studies. Notwithstanding, results have been traditionally acquired using 2-dimensional contrast-enhanced US, which implies that a majority of perfused tissue is omitted from analysis because this modality is inherently a planar imaging assessment. Overcoming this limitation via development of real-time volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging techniques and data-processing strategies has been shown to improve perfusion measurements because the entire tumor burden is considered.25 The purpose of our study was to determine whether volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging could detect the early tumor response to TRA-8 therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy in a preclinical TNBC animal model.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The 2LMP metastatic subclone of the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Mediatech Inc, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). Cells were cultured in 150-cm2 flasks (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA). At approximately 80% confluency, cells were harvested by trypsinization, and cell counts were determined using a hemacytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA) and trypan blue dye (Mediatech Inc) exclusion.

Animal Preparation

Animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Thirty 6-week-old nude female athymic mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were implanted with 2 × 106 cancer cells in the left flank. Three weeks after implantation, a vascular access port (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL) was surgically implanted via a jugular vein suture in all animals9 and allowed at least 5 days to properly recover from the surgery. Figure 1 illustrates subcutaneous port placement with respect to flank tumors. Vascular access ports were flushed daily using 0.1-mL injections of 10% heparin sodium solution in saline (AAP Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Schaumburg, IL) to prevent blood coagulation.

Figure 1.

Illustration of a surgically placed subcutaneous vascular access port in the animal model with respect to implanted flank tumors.

After surgical recovery and baseline volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging, animals were sorted by tumor size (determined using caliper measurements) and assigned to 1 of 4 treatment groups, namely, Abraxane (paclitaxel; Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ; n = 7), TRA-8 (n = 8), TRA-8 + Abraxane (n = 8), or control (n = 7). Animals were treated twice per week with the same therapy dosing (0.2 mg) for 3 weeks. Control group animals received equivalent injections of saline only. A time line of US imaging and therapeutic dosing relative to tumor cell implantation is detailed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Time line of both longitudinal volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging and the treatment schedule. After tumor cell implantation, baseline US scans were performed prior to treatment. Animals were euthanized throughout the study in accordance with established criteria for allowable tumor size. At day 21 after baseline, all remaining animals were euthanized. Tumors were excised from every animal and processed for immunohistologic analysis.

Ultrasound Imaging

Imaging was performed prior to drug dosing at day 0 and at days 1, 3, and 7 thereafter using the portable SonixTablet US system (Ultrasonix Medical Corporation, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada) equipped with a broadband 4DL14-5/38 volumetric probe. A pulse inversion harmonic imaging mode was used to improve detection of microbubble signals (mechanical index of 0.3, transmit at 5 MHz, and receive at 10 MHz). With a single adjustable beam focus set to 13 mm and proximal to the tumor burden, this motorized transducer has a line density of 128 elements (300-µm pitch) and maximum motor field of view (FOV) of 55.0° at 636 steps (0.086° per step). Backscattered radio-frequency (RF) data were decimated by the system at a rate of 20 MHz. Animals were maintained under isoflurane anesthesia while imaging was performed in a water bath setup at a temperature of 37°C. The transducer was fixed (Assist positioning arm; CIVCO Medical Solutions, Kalona, IA) to minimize motion and registration artifacts when processing.

After activation, a US contrast agent (Definity; Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA) was suspended in saline (1:3 dilution) and slowly infused via the surgically placed animal injection ports at a rate of 0.2 mL/min using a syringe pump (New Era Pump Systems Inc, Farmingdale, NY). Acquisition of backscattered RF data was controlled using the research-based software package Propello (Ultrasonix Medical Corporation). The graphical user interface allows customization of US scans to achieve the desired FOV and volume rate. Specifically, automatic sweeps were implemented with degrees per frame and frames per volume set to 0.692 and 40, respectively. Given an FOV x(width) and FOV y (depth) of 38.4 and 25.0 mm, respectively, this process allowed for an FOV z (elevation) of 28.4 mm and volume rate of 1.7 Hz (69 frames per second). Voxel sizes were 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.6 mm (width × depth × elevation). Ultrasound data were acquired for 60 seconds, and all imaging system settings were fixed for all sessions. Imaging data were saved for offline processing using techniques described below.

Image Processing

Custom programs were developed using the software package MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) that allowed processing of volumetric US image data. For all raw RF image data (after pulse inversion summation), harmonic signals (at 10 MHz) were further isolated from each beam line using a 31-tap Butterworth bandpass filter prior to envelope detection (Hilbert transform), low-pass filter smoothing, and scan conversion (bicubic interpolation). Because US imaging was initiated at the onset of microbubble infusion, the time history of data acquisition contained a reference period prior to contrast agent arrival in the FOV. The first volume (intensity) from each volumetric contrast-enhanced US scan was used as background reference intensity with all subsequent image volumes normalized by this reference. Motion compensation based on 2-dimensional cross-correlation techniques was used to correct and minimize any misalignment between the initial volume and all subsequent volume scans. Image data were then analyzed voxel by voxel to generate a maximum-intensity projection image through time for each volumetric data sequence to reflect tumor blood flow properties. A spherical region of interest was defined for each parametric map, and maximum-intensity projection values were averaged for each animal and time point. The region of interest size and placement were adjusted for each tumor to ensure that only intratumoral perfusion data were incorporated and no peripheral tissue. For each animal, all longitudinal perfusion estimates were recorded as percent change from the average intragroup baseline measurement and reported as mean group values. Figure 3 depicts the volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging system used for this study and the corresponding voxel-by-voxel data-processing strategy.

Figure 3.

Description of the real-time volumetric contrast-enhanced US system, which was developed using a portable research scanner (A) and a 4-dimensional probe (B). After collection of multidimensional volumetric data (C), custom software (D) analyzed time-intensity curve information voxel by voxel to derive the maximum intensity value of microbubble circulation (IMAX) representing a surrogate measurement of tumor perfusion.

Immunohistologic Analysis

After experimentation, animals were humanely euthanized, and tumors were surgically excised. Using established protocols, sectioned tumors (along the single largest transverse tumor area) underwent staining with hematoxylin-eosin and CD31 antibodies for microvessel density quantification. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling was used to detect apoptotic programmed cell death. Histologic findings were reviewed by an experienced reader blinded to the experimental groups. Each CD31 section was analyzed (original magnification ×40) to identify 5 separate areas containing the greatest number of microvessels. Individual vessels from these 5 areas were counted (original magnification ×200), averaged, and recorded as microvessel density. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeled sections were examined for stained apoptotic cells and reported as the percentage of the entire tumor cross section (original magnification ×40).

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard error. A logarithm transformation was used to transform all measurements. Longitudinal imaging measurements were assessed using a repeated measures analysis of variance test. Differences in volumetric contrast-enhanced US-based imaging measurements, tumor sizes, and immunohistologic data were evaluated using an independent 2-sample t test. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust confidence levels for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Inc, Cary, NC). P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Contrast-enhanced US images were collected in a preclinical TNBC animal model to determine feasibility for the assessment of the early tumor response to combination TRA-8 + Abraxane therapy. After microbubble infusion and acquisition of a 60-second sequence of volumetric RF backscatter data, custom image-processing software was used to generate a maximum-intensity map of tumor blood flow using time-intensity voxel information. As illustrated in Figure 4, these spatial blood flow maps describe tumor perfusion across the entire tumor volume. Due to the observed heterogeneity in tumor perfusion patterns, volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging allows a more detailed view of microbubble (and blood) flow dynamics compared to planar imaging techniques.25,26

Figure 4.

Spatial sequence of perfusion maps (maximum-intensity projection values) constituting a volumetric scan of tumor vascularity following microbubble infusion. The color bar denotes low and high maximum-intensity projection values. Note the predominance of blood flow on the tumor periphery versus the hypovascular tumor core.

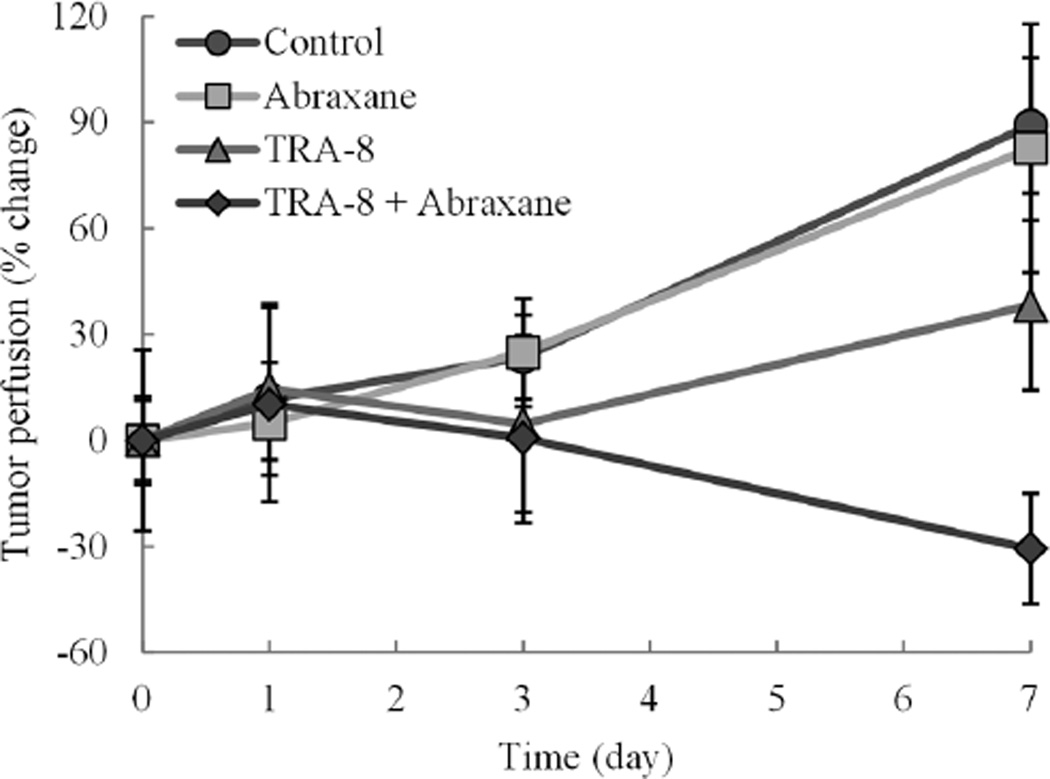

Longitudinal changes in US-based intratumoral perfusion measurements are summarized in Figure 5. Repeated measures in control animals revealed a significant increase in tumor perfusion (P = .02) relative to baseline estimates and mirrored the response observed in animals administered Abraxane alone (P = .17). Throughout the 7-day period of volumetric contrast-enhanced US monitoring, animals dosed with TRA-8 alone also exhibited an overall increase in tumor perfusion (P = .37), but tumor perfusion was considerably less than that observed in both the control and Abraxane-dosed specimens. Conversely, animals treated with TRA-8 + Abraxane exhibited an overall decrease in intratumoral perfusion measurements (P= .17). Compared to control data, changes in volumetric contrastenhanced US-based intratumoral perfusion measurements at day 3 were comparable in the Abraxane group (23.5% ± 11.9% versus 24.9% ± 15.4%; P = .34) but lower in the TRA-8 (23.5% ± 11.9% versus 4.7% ± 25.1%; P= .37) and TRA-8 + Abraxane (23.5% ± 11.9% versus 0.7% ± 24.0%; P = .81) groups. When compared to control data on day 7 of the study, changes in intratumoral perfusion measurements were lower in both the Abraxane (89.2% ± 19.1% versus 82.7% ± 35.2%; P = .47) and TRA-8 (89.2% ± 19.1% versus 38.2% ± 24.0%; P= .13) groups but significantly lower in the TRA-8 + Abraxane group (89.2% ± 19.1% versus −30.7% ± 15.6%; P = .001). Collectively, these findings suggest that unique signatures in intratumoral volumetric contrast-enhanced US-derived perfusion profiles allow detection of early tumor responses to TRA-8 and TRA-8 + Abraxane therapy when compared to control measurements.

Figure 5.

Summary of volumetric contrast-enhanced US-based tumor perfusion measurements derived from spherical regions of interest incorporating intratumoral vascularity. Longitudinal changes in maximum-intensity projection measurements are reported as percent change from baseline estimates.

Changes in physical tumor size recorded throughout this study are plotted in Figure 6. Although no differences were noted at baseline (P = .99), increases in tumor size measurements (relative to baseline) were observed by day 3 in all experimental groups: controls (15.9% ± 5.0%; P= .006), Abraxane (7.7% ± 6.3%; P = .04), TRA-8 (3.0% ± 6.6%; P = .04), and TRA-8 + Abraxane (1.8% ± 4.3%; P = .08). By day 7 of the study, significant increases in tumor size were still observed in the control (69.6% ± 11.7%; P < .001) and Abraxane (52.1% ± 10.7%; P = .03) group animals, whereas increases trended toward significance in the TRA-8-dosed animals (27.3% ± 11.6%; P= .06). Conversely, animals administered TRA-8 + Abraxane treatment exhibited a discernible reduction in tumor size (−19.9% ± 11.6%; P = .21).

Figure 6.

Description of the longitudinal changes in tumor volume in response to drug treatment throughout the study duration. Note that the error bars on the last control data point are too small to be visible.

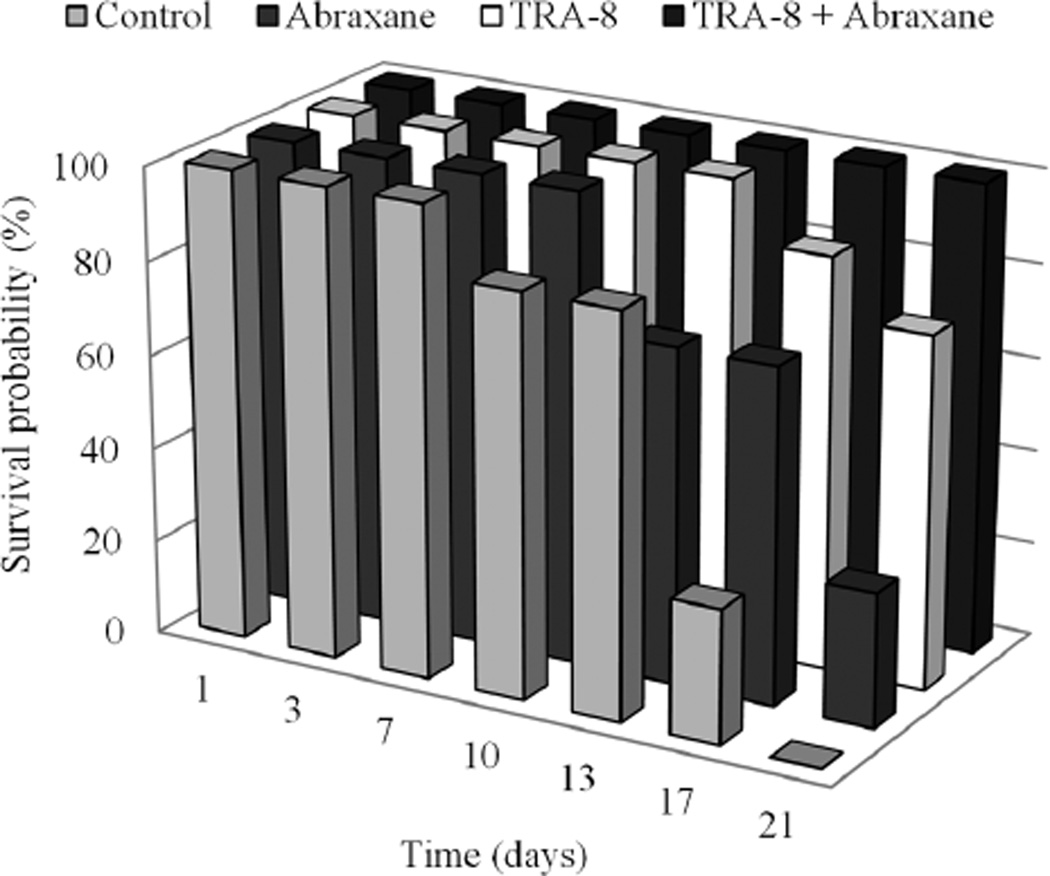

Animal monitoring for 21 days after initial therapy administration allowed generation of survival probability graphs (Figure 7). Prior to study completion, all control animals had been terminated due to tumor size and animal regulations. Animals administered Abraxane fared slightly better, as 28.6% (2 of 7) remained at day 21. An improved response was observed in the TRA-8-dosed animals, of which 75.0% (6 of 8) survived the duration of the study. Last, when Abraxane was combined with TRA-8 therapy, survival probability was 100% (8 of 8) and matched by physical reductions in tumor size.

Figure 7.

Longitudinal analysis of the survival probability for each treatment group.

Figure 8 details immunohistologic findings from excised tumor samples. Compared to control data, no significant intergroup differences were found in either intratumoral microvessel density (P > .17) or necrosis (P > .82) levels.

Figure 8.

Representative images and summary of immunohistologic results from excised tumor samples depicting intratumoral apoptosis (A) and microvessel density (B) levels for each treatment group. Arrows in Aand B indicate apoptotic cells and tumor microvessels, respectively.

Analysis of apoptotic activity found no differences between control and Abraxane-treated tumors (24.4% ± 3.4% versus 24.9% ± 2.8%; P = .99). However, animals administrated TRA-8 alone (42.9% ± 3.4%) or the combination of TRA-8 + Abraxane (56.5% ± 5.1%) were more sensitive to treatment and showed significantly higher levels of apoptosis-induced cell death when compared to control tumors (P = .001; P < .001, respectively).

Discussion

The common approach to most anticancer drugs is to control and contain the growth of cancer cells. The TRA-8 anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody induces apoptosis, whereas Abraxane, a chemotherapeutic, is a mitotic inhibitor used in the treatment of TNBC. Using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, researchers have noted reduced tumor perfusion levels after administering TRA-89 or taxane27 drugs. Although the exact mechanisms are still not understood, therapy-induced vascular damage and hemorrhagic necrosis have been considered as sources for this phenomenon.28 Importantly, early changes in tumor vascularity following systemic drug treatment introduce an opportunity to assess early therapeutic efficacy using tumor perfusion imaging techniques.10,25

The efficacy of combination TRA-8 + Abraxane therapy was detected within 7 days after drug administration using parametric volumetric contrast-enhanced US imaging. Compared to control tumors, decreased tumor perfusion levels were observed in both the TRA-8-alone– and TRA-8 + Abraxane–dosed animals. The latter reduction was statistically significant (P = .001) and was matched with a corresponding regression in tumor size over the same period. Importantly, although no changes in tumor size were noted on day 3 of the study, there was a pronounced difference in perfusion measurements between control and TRA-8-treated tumors. These findings suggest that unique signatures in volumetric contrast-enhanced US-derived tumor perfusion (parametric image) profiles might allow early detection of cancer responses to therapy. Survival curves illustrate that the combination of TRA-8 + Abraxane improves drug efficacy compared to the same drugs administered alone. These results further show that TRA-8 sensitizes breast cancer to chemotherapeutic dosing.29,30 Immunohistologic analysis revealed increased levels of apoptotic activity in the TRA-8-dosed tumors, which confirms enhanced antitumor effects.

In conclusion, parametric mapping of tumor vascularity using volumetric contrast-enhanced US was introduced and shown to be a promising modality for monitoring changes in tumor perfusion following systemic treatment. Overall, preliminary results are encouraging, and volumetric contrast-enhanced US-based tumor perfusion imaging may prove clinically feasible for detecting and monitoring early antitumor effects in response to cancer drug therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kurt R. Zinn, DVM, PhD, and Heidi Umphrey, MD, for insightful comments and Ultrasonix Medical Corporation for support of this research project. This work was funded by National Cancer Institute Grants 5P50CA089019 and CA13148 to the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- DR

death receptor

- FOV

field of view

- RF

radiofrequency

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- US

ultrasound

References

- 1.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhary PM, Eby M, Jasmin A, Bookwalter A, Murray J, Hood L. Death receptor 5, a new member of the TNFR family, and DR4 induce FADD-dependent apoptosis and activate the NF-kappaB pathway. Immunity. 1997;7:821–830. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuang AA, Diehl GE, Zhang J, Winoto A. FADD is required for DR4-and DR5-mediated apoptosis: lack of trail-induced apoptosis in FADD-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25065–25068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walczak H, Degli-Esposti MA, Johnson RS, et al. TRAIL-R2: a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. EMBO J. 1997;16:5386–5397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchsbaum DJ, Zhou T, Grizzle WE, et al. Antitumor efficacy of TRA-8 anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody alone or in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy in a human breast cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3731–3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchsbaum DJ, Zhou T, Lobuglio AF. TRAIL receptor-targeted therapy. Future Oncol. 2006;2:493–508. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H, Morgan DE, Zeng H, et al. Breast tumor xenografts: diffusion-weighted MR imaging to assess early therapy with novel apoptosis-inducing anti-DR5 antibody. Radiology. 2008;248:844–851. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483071740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Folks KD, Guo L, et al. DCE-MRI detects early vascular response in breast tumor xenografts following anti-DR5 therapy. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:94–103. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoyt K, Warram JM, Umphrey H, et al. Determination of breast cancer response to bevacizumab therapy using contrast-enhanced ultrasound and artificial neural networks. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:577–585. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucidarme O, Kono Y, Corbeil J, et al. Angiogenesis: noninvasive quantitative assessment with contrast-enhanced functional US in murine model. Radiology. 2006;239:730–739. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2392040986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pysz MA, Foygel K, Rosenberg J, Gambhir SS, Schneider M, Willmann JK. Antiangiogenic cancer therapy: monitoring with molecular US and a clinically translatable contrast agent (BR55) Radiology. 2010;256:519–527. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willmann JK, Paulmurugan R, Chen K, et al. US imaging of tumor angiogenesis with microbubbles targeted to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 in mice. Radiology. 2008;246:508–518. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willmann JK, Cheng Z, Davis C, et al. Targeted microbubbles for imaging tumor angiogenesis: assessment of whole-body biodistribution with dynamic micro-PET in mice. Radiology. 2008;249:212–219. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491072050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willmann JK, Kimura RH, Deshpande N, Lutz AM, Cochran JR, Gambhir SS. Targeted contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of tumor angiogenesis with contrast microbubbles conjugated to integrin-binding knottin peptides. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:433–440. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson CR, Hu X, Zhang H, et al. Ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis with an integrin targeted microbubble contrast agent. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:215–224. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182034fed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsberg F, Ro RJ, Fox TB, et al. Contrast enhanced maximum intensity projection ultrasound imaging for assessing angiogenesis in murine glioma and breast tumor models: a comparative study. Ultrasonics. 2011;51:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rychak JJ, Graba J, Cheung AM, et al. Microultrasound molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in a mouse model of tumor angiogenesis. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhayana D, Kim TK, Jang HJ, Burns PN, Wilson SR. Hypervascular liver masses on contrast-enhanced ultrasound: the importance of washout. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:977–983. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischer AC, Lyshchik A, Andreotti RF, Hwang M, Jones HW, Fishman DA. Advances in sonographic detection of ovarian cancer: depiction of tumor neovascularity with microbubbles. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:343–348. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gauthier TP, Wasan HS, Muhammad A, Owen DR, Leen EL. Assessment of global liver blood flow with quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:379–385. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goetti R, Reiner CS, Knuth A, et al. Quantitative perfusion analysis of malignant liver tumors: dynamic computed tomography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:18–24. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318229ff0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lassau N, Chami L, Chebil M, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultra-sonography (DCE-US) and anti-angiogenic treatments. Discov Med. 2011;11:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassau N, Koscielny S, Chami L, et al. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: early evaluation of response to bevacizumab therapy at dynamic contrast-enhanced US with quantification—preliminary results. Radiology. 2011;258:291–300. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoyt K, Sorace AG, Saini R. Quantitative mapping of tumor vascularity using volumetric contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:1–8. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318234e6bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feingold S, Gessner R, Guracar IM, Dayton PA. Quantitative volumetric perfusion mapping of the microvasculature using contrast ultrasound. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:669–674. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ef0a78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martincich L, Bertotto I, Montemurro F, et al. Variation of breast vascular maps on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI after primary chemotherapy of locally advanced breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1214–1218. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denekamp J. Review article: angiogenesis, neovascular proliferation and vascular pathophysiology as targets for cancer therapy. Br J Radiol. 1993;66:181–196. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-66-783-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amm HM, Zhou T, Steg AD, Kuo H, Li Y, Buchsbaum DJ. Mechanisms of drug sensitization to TRA-8, an agonistic death receptor 5 antibody, involve modulation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:403–417. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derosier LC, Vickers SM, Zinn KR, et al. TRA-8 anti-DR5 monoclonal antibody and gemcitabine induce apoptosis and inhibit radiologically validated orthotopic pancreatic tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3198–3207. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]