Abstract

Objective

To understand why children exposed to adverse psychosocial experiences are at elevated risk for age-related disease, such as cardiovascular disease, by testing whether adverse childhood experiences predict enduring abnormalities in stress-sensitive biological systems, namely, the nervous, immune, and endocrine/metabolic systems.

Design

A 32-year prospective longitudinal study of a representative birth cohort.

Setting

New Zealand.

Participants

A total of 1037 members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study.

Main Exposures

During their first decade of life, study members were assessed for exposure to 3 adverse psychosocial experiences: socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment, and social isolation.

Main Outcome Measures

At age 32 years, study members were assessed for the presence of 3 age-related-disease risks: major depression, high inflammation levels (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level >3 mg/L), and the clustering of metabolic risk biomarkers (overweight, high blood pressure, high total cholesterol, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high glycated hemoglobin, and low maximum oxygen consumption levels.

Results

Children exposed to adverse psychosocial experiences were at elevated risk of depression, high inflammation levels, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Children who had experienced socioeconomic disadvantage (incidence rate ratio, 1.89; 95% confidence interval, 1.36–2.62), maltreatment (1.81; 1.38–2.38), or social isolation (1.87; 1.38–2.51) had elevated age-related-disease risks in adulthood. The effects of adverse childhood experiences on age-related-disease risks in adulthood were nonredundant, cumulative, and independent of the influence of established developmental and concurrent risk factors.

Conclusions

Children exposed to adverse psychosocial experiences have enduring emotional, immune, and metabolic abnormalities that contribute to explaining their elevated risk for age-related disease. The promotion of healthy psychosocial experiences for children is a necessary and potentially cost-effective target for the prevention of age-related disease.

DECLINING FERTILITY RATES and increasing life expectancy are leading to global population aging.1 As the population ages, the public health impact of age-related conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and dementia, increases.2 Consequently, effective strategies are needed to prevent age-related diseases and to improve the quality of longer lives. Interventions targeting modifiable risk factors (eg, smoking, inactivity, and poor diet) in adult life have only limited efficacy in preventing age-related disease.3,4 Because of the increasing recognition that preventable risk exposures in early life may contribute to pathophysiological processes leading to age-related disease,5,6 the science of aging has turned to a life-course perspective.7,8 Capitalizing on this perspective, this study tested the contribution of adverse psychosocial experiences in childhood to 3 adult conditions that are known to predict age-related diseases: depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers, hereinafter referred to as age-related-disease risks.

AGE-RELATED-DISEASE RISKS

Depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers indicate abnormal functioning of stress-sensitive systems.9 These 3 conditions also predict age-related diseases. First, depression has been linked to multiple biological abnormalities, including vascular pathologic changes, autonomic function changes, hypercoagulability, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity.10 Evidence shows that depression in adulthood is linked to elevated risk of developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and dementia in later life.11 Second, inflammation contributes to atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and neurodegeneration.12–14 Evidence shows that elevation in inflammation biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), in adulthood predicts the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and dementia in later life.15–17 Third, metabolic abnormalities such as obesity, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, hypertension, and cardiorespiratory fitness contribute to vascular lesions and hormonal imbalance. These abnormalities tend to cluster in the same individuals.18,19 Evidence shows that the clustering of metabolic risk markers in adulthood is associated with elevated risk of developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and dementia in later life.18,20 Importantly, depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers frequently co-occur in the same individuals, and their co-occurrence is associated with the greatest disease risk.20,21 To improve life quality in aging populations, it is critical to gain a better understanding of the origins of these 3 age-related-disease risks. Because adverse childhood experiences may disrupt the physiological response to stress,22,23 they may influence the risk for depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers.

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES

Increasing evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences may contribute to depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers. Among adverse childhood experiences, 3 stand out as contributing factors: low socioeconomic status (SES), maltreatment, and social isolation. First, low SES in childhood is a recognized risk factor for age-related disease, such as cardiovascular disease.24 Childhood socioeconomic disadvantage predicts age-related-disease risks, such as elevated inflammation levels and the clustering of metabolic risk markers in adulthood.25–27 In contrast, the effect of low childhood SES on later depression risk is debated.28 Second, retrospective investigations and some prospective studies have shown that childhood maltreatment could contribute to age-related-disease risks. Childhood maltreatment is a documented predictor of adult depression.29 Emerging evidence suggests that childhood maltreatment may also contribute to the risk of inflammation and metabolic risk markers in adult life.30–32 Third, it is increasingly recognized that individuals experiencing social isolation are at greater risk for disease.33–35 Adverse psychosocial experiences such as social isolation could be particularly detrimental in the developing child,36 and initial findings suggest that childhood social isolation may have enduring effects on the clustering of metabolic risk markers in adult life.37

RESEARCH NEEDS

Most studies to date have examined—one at a time—the association between a single adverse childhood experience and a single age-related-disease risk (eg, low childhood SES and elevated adult inflammation26 or child-hood maltreatment and adult depression29). Three important questions have therefore been left unaddressed. First, are the effects of different adverse childhood experiences distinct from each other? To the extent that multiple adverse childhood experiences co-occur in the same individuals, it is possible that their effects on adult health are not independent and unique. Second, are the effects of different adverse childhood experiences pervasive in different biological systems? Each adverse childhood experience may influence a single age-related-disease risk in a single stress-sensitive system, or, alternately, each adverse experience could influence multiple age-related-disease risks. Third, are the effects of adverse childhood experiences independent of the influence of other known risk factors for age-related disease? Adverse psychosocial experiences in childhood are likely to be accompanied by other developmental risk factors for poor adult health, including family history of disease,38 low birth weight,39 and childhood overweight.40 It is thus important to test whether adverse psychosocial experiences in childhood exert an influence on adult outcomes that is independent of these established risk factors.

The present study addresses these 3 gaps. We followed up a population-representative birth cohort from childhood to age 32 years and tested whether measures of low SES, maltreatment, and social isolation assessed in the first decade of life predicted the occurrence of depression and inflammation and the clustering of metabolic risk markers assessed in adulthood. Analyses controlled for established developmental and current (adult) risk factors for age-related disease.

METHODS

SAMPLE

Participants are members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a complete birth cohort. Study members (N=1037; 91% of eligible births; 52% male) were born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, and participated in the first follow-up assessment at age 3 years. The cohort represents the full range of SES in the general population of New Zealand’s South Island and is primarily white. Assessments have been carried out at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, and 32 years, when study members attended the Study Research Unit for a full day of individual data collection. This investigation is based on study members who completed the assessment at age 32 years (n=972; 95.8% of the 1015 study members still alive in 2004–2005). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating universities. Study members gave informed consent before participating.

MEASURES OF AGE-RELATED-DISEASE RISKS AT AGE 32 YEARS

Psychiatric and physical examinations were conducted at age 32 years for 892 study members (91.8%) who provided blood samples (venipunctures were always performed between 4:15 and 4:45 PM). Twenty-six pregnant women were excluded from the reported analyses.

Adult Major Depression

As previously described,41 study members were interviewed by health professionals using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule42 with a reporting period of 12 months. Depression was diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).43

Adult High-Sensitivity CRP

As previously described,30 high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) was measured on a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (Hitachi 917 analyzer; Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). A definition of high cardiovascular risk according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association (hsCRP level >3 mg/L) was adopted to identify our risk group.44 (To convert hsCRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524.)

Adult Clustering of Metabolic Risk Markers

As previously described,37 health risk-factor clustering was assessed by measuring 6 biomarkers: (1) overweight, (2) high blood pressure, (3) high total cholesterol, (4) low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, (5) high glycated hemoglobin, and (6) low maximum oxygen consumption levels adjusted for body weight. The number of biomarkers on which each study member was at risk was summed, and study members who had at least 3 risk factors were defined as having clustered metabolic risk.

Number of Age-Related-Disease Risks

These 3 indicators of age-related-disease risk were linked, but they were not redundant. For example, study members with an hsCRP level greater than 3 mg/L were more likely to have clustering of metabolic risk markers (risk ratio [RR], 2.56; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.91–3.43) and to be depressed (1.49; 1.06–2.09), but 60.6% of study members with metabolic risk marker clustering and 72.6% of study members with depression did not have an hsCRP level greater than 3 mg/L. Similarly, most study members with depression (83.1%) did not have clustering of metabolic risk markers. Because previous research has shown that depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers have cumulative effects on clinical outcomes,20,21 we summed these 3 age-related-disease risks for each Dunedin Study member and found that 59.5% of study members had none of the risks, 30.2% had 1 risk, and 10.3% had 2 or more risks.

MEASURES OF ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES

The assessment of study members’ exposure to adverse childhood experiences covered the first decade of their lives.

Childhood Low SES

As previously described,25 the SES of the study members’ parents was measured on a scale that placed occupations into one of 6 categories (with 1 indicating professional and 6, unskilled laborer) based on education and income associated with that occupation in data from the New Zealand census.45 To define childhood SES, we first identified at each assessment the highest SES of either parent and then averaged those measures over repeated assessments from study members’ birth to age 15 years. Study members were divided into 3 SES groups: high (16.2% of study members; groups 1 and 2: eg, manager or physician), intermediate (64.1%; groups 3 and 4: eg, secretary or electrician), and low (19.7%; groups 5 and 6: eg, cashier or textile machine operator).

Childhood Maltreatment

As previously described,46 the measure of childhood maltreatment includes (1) maternal rejection assessed at age 3 years by observational ratings of mothers’ interaction with the study children, (2) harsh discipline assessed at ages 7 and 9 years by parental report of disciplinary behaviors, (3) 2 or more changes in the child’s primary caregiver, and (4) physical abuse and (5) sexual abuse reported by study members once they reached adulthood. For each child, our cumulative index counts the number of maltreatment indicators during the first decade of life; 63.7% of children experienced no maltreatment, 26.7% experienced 1 indicator of maltreatment (hereinafter “probable” maltreatment), and 9.6% experienced 2 or more indicators of maltreatment (“definite” maltreatment).

Childhood Social Isolation

Evidence shows that chronic social isolation predicts poor prognosis, and repeated assessment of children’s peer experiences is therefore recommended for research purposes.47 As previously described,37 2 items of the Rutter Child Scale that measure social isolation (“tends to do things on his/her own; is rather solitary” and “not much liked by other children”) were reported about each study member at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 years by their parents and teachers. Scores on these 2 items were averaged across the 4 time periods and the 2 reporters (Cronbach α=0.77). The samplewide distribution of childhood social isolation scores was divided into quartiles (very low, low, high, and very high) for analysis.

Number of Adverse Childhood Experiences

The 3 adverse childhood experiences were linked but were not redundant. For example, children growing up with low childhood SES were more likely to be maltreated (RR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.83–3.94) and to be socially isolated (1.62; 1.31–2.02), but 58.5% of maltreated children and 70.1% of socially isolated children were not exposed to low SES. Similarly, maltreated children were more likely to be socially isolated (RR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.22–2.11), but most of the isolated children (86.0%) were not maltreated. Because multiple adverse childhood experiences may have a cumulative effect on age-related-disease risks, we summed the number of adverse childhood experiences for each study member: 57.8% of study members had no adverse childhood experiences, 30.3% had 1, and 11.9% had 2 or more.

ESTABLISHED DEVELOPMENTAL RISK FACTORS FOR AGE-RELATED DISEASE

Family History of Cardiovascular Disease and Depression

In 2003–2006, the history of mental and physical disorders was assessed for the study members’ biological parents. Both parents were interviewed (86.2%) or one reported for both (13.8%). Parental history of depression was assessed with the Family History Screen.48 Parental history of heart disease (defined as a history of heart attack, balloon angioplasty, coronary bypass, or angina) was assessed following guidelines from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study.49 It was not possible to assess family history of inflammation.

Birth Weight

Children’s birth weight was obtained from hospital records.

Childhood Body Mass Index

Childhood body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was defined as the average of sex- and age-standardized BMIs as calculated from physical measurements taken at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 years.

ESTABLISHED CURRENT RISK FACTORS FOR AGE-RELATED DISEASE

Current Low SES

To determine current SES, study members’ current or most recent occupation at age 32 years was coded according to the 6-point scale for contemporary occupations in New Zealand; homemakers and those not working were prorated according to their level of education.50

Current Smoking

At age 32 years, study members were divided into nonsmokers, light smokers (≥10 cigarettes per day), moderate smokers (11–20), and heavy smokers (>20).

Current Physical Activity

Study members were interviewed about their amount and type of physical activity in the week preceding the assessment at age 32 years and about their personal effort involved in carrying out specific activities. According to guidelines proposed by Ainsworth et al,51 interviewers rated physical activity as light, moderate, hard, and very hard. The total metabolic equivalent score for the week was calculated as the weighted sum of the time spent in each activity. The samplewide distribution of metabolic equivalent scores was divided into quartiles for analysis.

Current Diet

At age 32 years, the study members reported their daily intake of fruits and vegetables because of the evidence linking Mediterranean-style diet with reduced age-related-disease risks.52 The samplewide distribution was divided into quartiles for analysis.

Current Medications

When study members were 32 years old, they were interviewed about their use of medications. The effect of antidepressants, systemic corticosteroids, respiratory corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prophylactic aspirin, antigout medications, antirheumatic medications, statins, and estrogens was examined.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Cox proportional hazards regression models with constant time of follow-up and robust variance were fitted to estimate the association between adverse childhood experiences and each of the categorical outcomes of age-related-disease risks at age 32 years. Poisson regression models were fitted to estimate the association between adverse childhood experiences and the number of age-related-disease risks at age 32 years. The regression models were then expanded to test the independence of the effects of adverse childhood experiences while controlling for established predictors of age-related-disease risks.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of depression (panel 1), elevated inflammation levels (panel 2), and clustering of metabolic risk markers (panel 3) in study members with different levels of exposure to childhood socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment, and social isolation.

Table 1.

Distribution of Age-Related-Disease Risks in Adults With Different Levels of Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiencesa

| No. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Childhood Experiences |

Panel 1: Major Depression |

Panel 2: hsCRP >3 mg/L |

Panel 3: Clustering of Metabolic Risk Markers |

| Childhood SES | |||

| High | 23 (16.6) | 18 (13.0) | 13 (9.4) |

| Average | 76 (13.9) | 113 (20.6) | 84 (15.3) |

| Low | 36 (21.3) | 43 (25.4) | 44 (26.0) |

| Childhood maltreatment | |||

| No | 69 (12.6) | 99 (18.0) | 76 (13.8) |

| Probable | 39 (17.0) | 49 (21.3) | 51 (22.2) |

| Definite | 27 (32.5) | 27 (32.5) | 15 (18.1) |

| Childhood social isolation | |||

| Very low | 19 (11.5) | 25 (15.1) | 18 (10.8) |

| Low | 34 (14.7) | 45 (19.5) | 28 (12.1) |

| High | 33 (13.4) | 53 (21.5) | 40 (16.2) |

| Very high | 48 (22.5) | 52 (24.4) | 54 (25.4) |

Abbreviations: hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SES, socioeconomic status.

SI conversion factor: To convert hsCRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524.

N = 862. Sample size may vary slightly because of missing values for childhood predictors.

PREDICTING DEPRESSION

The established developmental risk factors of family history of depression and low birth weight predicted adult depression at age 32 years (Table 2, panel 1, bivariate analysis). After controlling for these established risk factors (Table 2, panel 1, multivariate analysis), children who were maltreated (definite maltreatment: RR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.13–2.55) and children who were socially isolated (very high social isolation: 1.76; 1.12–2.77) were both at greater risk of becoming depressed in adulthood. Under the assumption of causality and independence, it was estimated that 31.6% of the cohort cases with depression were attributable to adverse childhood experiences.

Table 2.

Prediction of 3 Age-Related-Disease Risks in Adults With Different Levels of Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Established Developmental Risk Factors

| Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1: Major Depression |

Panel 2: hsCRP >3 mg/L |

Panel 3: Clustering of Metabolic Risk Markers |

||||

| Bivariatea | Multivariateb | Bivariatea | Multivariateb | Bivariatea | Multivariateb | |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences | ||||||

| Childhood SES | ||||||

| High | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Average | 0.78 (0.53–1.15) | 0.90 (0.60–1.34) | 1.59 (1.00–2.52) | 1.55 (0.98–2.46) | 1.53 (0.89–2.61) | 1.52 (0.89–2.57) |

| Low | 1.22 (0.80–1.87) | 1.14 (0.72–1.79) | 1.96 (1.19–3.25) | 1.63 (0.98–2.70) | 2.65 (1.52–4.62) | 2.11 (1.20–3.70) |

| Childhood maltreatment | ||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Probable | 1.18 (0.84–1.66) | 1.07 (0.76–1.51) | 1.18 (0.87–1.60) | 1.16 (0.85–1.58) | 1.56 (1.13–2.14) | 1.39 (1.01–1.93) |

| Definite | 2.28 (1.58–3.27) | 1.69 (1.13–2.55) | 1.80 (1.26–2.58) | 1.56 (1.08–2.26) | 1.28 (0.77–2.11) | 1.04 (0.65–1.67) |

| Childhood social isolation | ||||||

| Very low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Low | 1.32 (0.80–2.16) | 1.35 (0.84–2.17) | 1.29 (0.83–2.02) | 1.31 (0.84–2.05) | 1.12 (0.64–1.95) | 1.14 (0.67–1.95) |

| High | 1.22 (0.74–2.00) | 1.20 (0.74–1.95) | 1.42 (0.92–2.20) | 1.39 (0.91–2.15) | 1.52 (0.90–2.55) | 1.34 (0.81–2.24) |

| Very high | 1.99 (1.25–3.17) | 1.76 (1.12–2.77) | 1.62 (1.05–2.50) | 1.60 (1.04–2.47) | 2.34 (1.43–3.83) | 1.96 (1.21–3.17) |

| Established Developmental Risk Factors | ||||||

| Family history | 1.88c (1.36–2.61) | 1.71c (1.23–2.39) | … | … | 1.74d (1.28–2.38) | 1.49d (1.09–2.03) |

| Birth weight | 0.72 (0.54–0.96) | 0.78 (0.59–1.04) | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | 0.78 (0.61–1.01) | 1.16 (0.86–1.56) | 0.91 (0.68–1.21) |

| Childhood BMI | 1.07 (0.91–1.27) | 1.10 (0.93–1.29) | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) | 1.13 (0.99–1.30) | 1.58 (1.41–1.78) | 1.53 (1.35–1.73) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ellipses, not assessed; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; SES, socioeconomic status.

Bivariate analyses show the association of single risk factors with age-related-disease risks.

Multivariate analyses show the association of single risk factors with age-related-disease risks while controlling for all other risk factors (ie, independent of the effect of other risk factors). Multivariate analyses are adjusted for sex and medication use.

Family history of major depression.

Family history of cardiovascular disease.

PREDICTING ELEVATED INFLAMMATION LEVELS

The established developmental risk factor of low birth weight predicted increased risk of inflammation in adulthood (Table 2, panel 2). After controlling for this established risk factor, children who were maltreated (definite maltreatment: RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.08–2.26) and children who were socially isolated (very high social isolation: 1.60; 1.04–2.47) were both at greater risk of elevated inflammation levels at age 32 years. It was estimated that 13.0% of the cohort cases with elevated inflammation were attributable to adverse childhood experiences.

PREDICTING THE CLUSTERING OF METABOLIC RISK MARKERS

The established developmental risk factors of family history of heart disease and high childhood BMI predicted the clustering of metabolic risk markers in adulthood (Table 2, panel 3). After controlling for these established risk factors, children growing up in socioeconomically disadvantaged families (low SES: RR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.20–3.70) and children who were socially isolated (very high social isolation: 1.96; 1.21–3.17) were both at greater risk of metabolic risk marker clustering at age 32 years. It was estimated that 32.2% of the cohort cases with clustering of metabolic risk markers were attributable to adverse childhood experiences.

PREDICTING THE NUMBER OF AGE-RELATED-DISEASE RISKS

Table 3 shows incidence rate ratios indexing the associations between adverse childhood experiences and the count of age-related-disease risks (ie, depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers) in adulthood. Three findings are noteworthy. First, all of the established developmental risk factors—namely, family history (both depression and heart disease), low birth weight, and high childhood BMI—predicted a greater number of age-related-disease risks at age 32 years (Table 3, panel 1). Second, as the severity of childhood socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment, and social isolation increased, the number of age-related-disease risks at age 32 years also increased; that is, each adverse childhood experience independently predicted a greater number of age-related-disease risks at age 32 years in a dose-response fashion (Table 3, panel 2). Third, even after taking into account the effects of (1) established developmental risk factors and (2) concurrent circumstances and behaviors such as low SES, smoking, physical inactivity, and poor diet at 32 years of age, each adverse childhood experience still predicted a greater number of age-related-disease risks at that age (Table 3, panels 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Prediction of Number of Age-Related-Disease Risks in Adults With Different Levels of Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Established Risk Factors

| Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Age-Related-Disease Risks at Age 32 yb |

||||

| Panel 1: Bivariate Analysis |

Panel 2: Adverse Childhood Experiences Model |

Panel 3: Developmental Risks Model |

Panel 4: Life-Course Model |

|

| Adverse Childhood Experiences | ||||

| Childhood SES | ||||

| High | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Average | 1.33 (0.99–1.80) | 1.36 (1.00–1.85) | 1.38 (1.02–1.88) | 1.36 (1.00–1.86) |

| Low | 1.89 (1.36–2.62) | 1.66 (1.19–2.33) | 1.60 (1.14–2.26) | 1.55 (1.09–2.21) |

| Childhood maltreatment | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Probable | 1.37 (1.11–1.69) | 1.28 (1.03–1.59) | 1.27 (1.02–1.57) | 1.26 (1.01–1.56) |

| Definite | 1.81 (1.38–2.38) | 1.59 (1.19–2.11) | 1.50 (1.12–2.01) | 1.55 (1.15–2.08) |

| Childhood social isolation | ||||

| Very low | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Low | 1.25 (0.91–1.71) | 1.24 (0.91–1.71) | 1.26 (0.92–1.72) | 1.26 (0.92–1.73) |

| High | 1.35 (0.99–1.84) | 1.31 (0.96–1.79) | 1.27 (0.93–1.74) | 1.29 (0.94–1.76) |

| Very high | 1.87 (1.38–2.51) | 1.73 (1.27–2.34) | 1.66 (1.22–2.25) | 1.63 (1.20–2.21) |

| Established Developmental Risk Factors | ||||

| Family history of depression | 1.33 (1.09–1.62) | … | 1.25 (1.02–1.53) | 1.23 (1.00–1.50) |

| Family history of CV disease | 1.30 (1.05–1.60) | … | 1.24 (1.00–1.54) | 1.24 (0.99–1.54) |

| Birth weight | 0.81 (0.68–0.97) | … | 0.78 (0.65–0.94) | 0.79 (0.66–0.95) |

| Childhood BMI | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | … | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) |

| Established Concurrent Risk Factors | ||||

| Adult SES | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | … | … | 0.88 (0.75–1.02) |

| Adult smoking | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) | … | … | 0.96 (0.87–1.07) |

| Adult physical activity | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | … | … | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) |

| Adult diet | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | … | … | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; ellipses, not assessed; SES, socioeconomic status.

Results are adjusted for sex and medication use.

Panel 1 shows the association of single risk factors with the number of age-related-disease risks. Panel 2 shows the nonredundant association of different adverse childhood experiences with the number of age-related-disease risks (ie, the prediction from one adverse childhood experience while controlling for the others). Panels 3 and 4 show, respectively, the independent association of different adverse childhood experiences with the number of age-related-disease risks while controlling for established developmental risk factors and while controlling for both established developmental risk factors and established concurrent risk factors.

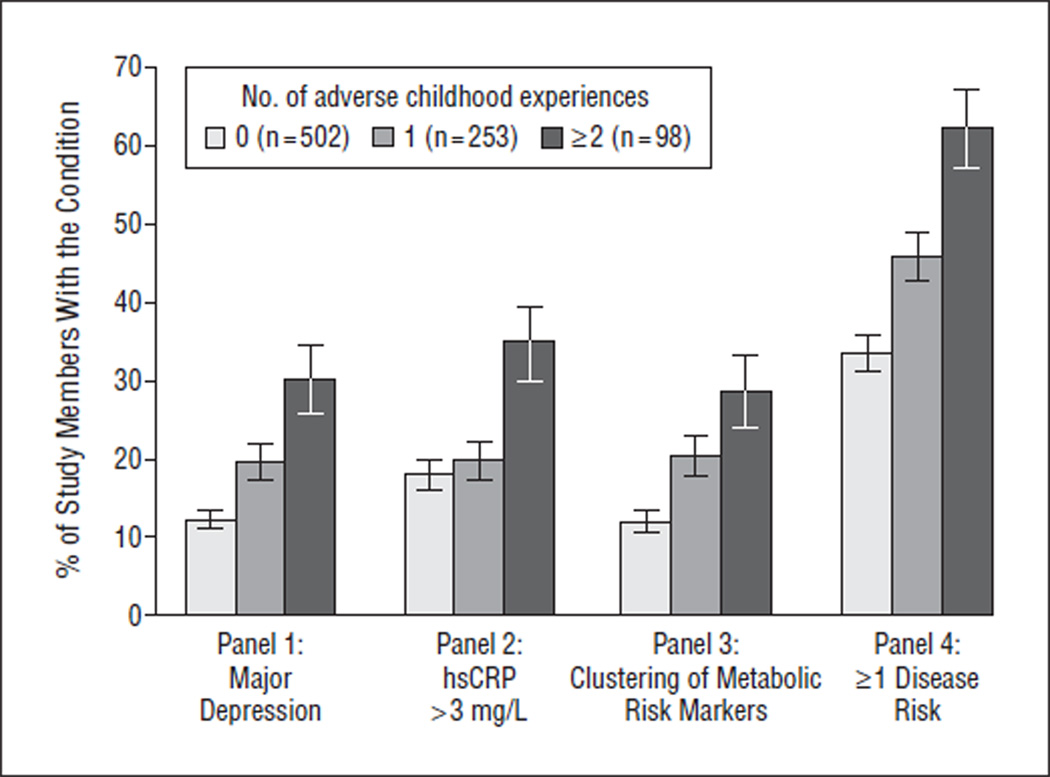

The Figure shows that the prevalence of adult depression (panel 1), elevated inflammation (panel 2), and the clustering of metabolic risk markers (panel 3) each increased as a function of the number of adverse childhood experiences. Furthermore, panel 4 shows that the risk of developing 1 or more of these 3 adult conditions was related to the number of adverse childhood experiences in a dose-response fashion.

Figure.

Distribution of mean (SD) age-related-disease risks at age 32 years with different levels of exposure to adverse childhood experiences (percentages and standard errors). Nonparametric tests for trend across increasing number of early adverse experiences were as follows: depression (panel 1): z=4.94, P<.001; high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level (hsCRP) level greater than3 mg/L (panel 2): z=3.24, P=.001; clustering of metabolic risk markers (panel 3): z=4.58, P<.001; and 1 or more age-related-disease risks (panel 4): z=5.66, P<.001. To convert hsCRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524.

COMMENT

This longitudinal-prospective study suggests that children experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment, or social isolation are more likely to present risk factors for age-related disease in adulthood, such as depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk factors. The enduring consequences of adverse childhood experiences were not explained by established developmental or concurrent risk factors. This research makes 4 contributions to knowledge about the connection between childhood rearing conditions and adult health.

First, our results indicate that groups of children exposed to different adverse experiences do not necessarily overlap; for example, most of the children experiencing maltreatment or social isolation did not experience socioeconomic disadvantage. Consequently, different adverse childhood experiences exerted independent effects on age-related-disease risks. This evidence suggests that different interventions are needed to tackle each adverse childhood experience. Relieving childhood poverty alone may be insufficient to reduce health inequalities associated with adverse childhood experiences.

Second, our results indicate that children exposed to a greater number of adverse experiences have a greater number of age-related-disease risks in adult life. The cumulative effect of adverse childhood experiences points to new opportunities for disease prevention. Whereas long-term social, political, and economic changes may be necessary to improve children’s socioeconomic conditions, 53,54 available interventions targeting childhood maltreatment55 and social isolation56 can be more readily implemented to prevent age-related disease. Because even successful interventions have had so far only modest impact, there is a need for continuing intervention innovations and program improvements. Adult health could be improved by targeting children’s modifiable psychosocial risk factors.

Third, our results indicate that children exposed to adverse psychosocial experiences have enduring abnormalities in multiple biological systems. There was some evidence of specificity, supporting previous observations that childhood socioeconomic disadvantage does not predict adult depression28 and suggesting that childhood maltreatment is a poor predictor of metabolic risk marker clustering. However, the overall picture emerging from our results was that adverse childhood experiences may simultaneously affect nervous, immune, and endocrine/ metabolic functioning in adulthood. This evidence extends previous experimental findings from animal models to humans.57–60 Our longitudinal findings are consistent with the hypothesis that adverse psychosocial experiences in childhood disrupt the physiological response to stress22,23 and that its chronic overactivation may lead to detrimental consequences in stress-sensitive systems, namely, the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems, or allostatic load.61 The resulting cumulative biological burden could increase risk for age-related disease.62 Improving the psychosocial environment of children may prevent multiple age-related-disease risks.

Fourth, our results indicate that children exposed to adverse experiences are more likely to have age-related-disease risks in adult life regardless of their familial liability for disease, birth weight, childhood weight, and adult SES and health behaviors. This evidence suggests that modifying established risk factors is unlikely to wholly mitigate the economic health burden associated with adverse childhood experiences.63 Promoting healthy psychosocial experiences for children may be necessary to improve the quality of longer lives and reduce health care costs across the life course.

These new findings should be examined alongside several study limitations. First, at age 32 years, study members were still too young to show age-related diseases. Instead, we focused on intermediate risk factors such as depression, inflammation, and the clustering of metabolic risk markers, which are known to predict age-related diseases.11,18,44 Although we were unable to measure disease outcomes, we believe that the investigation of relevant intermediate pathways may contribute to characterizing life-course health trajectories. Second, findings from this New Zealand cohort require replication in other countries. However, childhood SES has been linked to cardiovascular disease in studies worldwide,24 which suggests that our results will replicate. Third, we focused our analyses on childhood socioeconomic disadvantage, maltreatment, and social isolation because previous research suggested a link between these measures and age-related disease.24,31,33 However, children may be exposed to other significant adverse experiences, and research is needed to uncover them.

In conclusion, it has long been known that patho-physiological processes leading to age-related diseases may already be under way in childhood.64 This study suggests the possibility that children’s experiences while growing up contribute to such physiological processes. Reducing damage done by adverse childhood experiences may help reduce the cost of age-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council. This research was supported by grants G0100527 and 60601483 from the UK Medical Research Council; grants MH45070, MH49414, and MH077874 from the National Institute for Mental Health; and grant AG032282 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr Danese is a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellow, Dr Pariante is a Medical Research Council Research Fellow, and Dr Caspi is a Royal Society-Wolfson Merit Award holder.

Additional Contributions: We thank the Dunedin Study members.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Danese had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Danese, Moffitt, Poulton, and Caspi. Acquisition of data: Moffitt, Poulton, and Caspi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Danese, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne, Polanczyk, Pariante, and Caspi. Drafting of the manuscript: Danese, Moffitt, and Caspi. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Danese, Moffitt, Harrington, Milne, Polanczyk, Pariante, Poulton, and Caspi. Statistical analysis: Danese, Harrington, and Milne. Obtained funding: Moffitt, Poulton, and Caspi. Administrative, technical, and material support: Danese, Harrington, and Poulton. Study supervision: Moffitt, Pariante, and Caspi.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature. 2008;451(7179):716–719. doi: 10.1038/nature06516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braunwald E. Shattuck lecture—cardiovascular medicine at the turn of the millennium: triumphs, concerns, and opportunities. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(19):1360–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebrahim S, Beswick A, Burke M, Davey Smith G. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease [update of: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000l; (2):CD001561] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001561. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGill HC, Jr, McMahan CA. Starting earlier to prevent heart disease. JAMA. 2003;290(17):2320–2322. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and earlylife conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkwood TB, Austad SN. Why do we age? Nature. 2000;408(6809):233–238. doi: 10.1038/35041682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finch CE, Crimmins EM. Inflammatory exposure and historical changes in human life-spans. Science. 2004;305(5691):1736–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1092556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders: overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis [published correction appears in JAMA. 1992;268(2):200] JAMA. 1992;267(9):1244–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(3):175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steptoe A, editor. Depression and Physical Illness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry VH, Cunningham C, Holmes C. Systemic infections and inflammation affect chronic neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(2):161–167. doi: 10.1038/nri2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):356] N Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):973–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo HK, Yen CJ, Chang CH, Kuo CK, Chen JH, Sorond F. Relation of C-reactive protein to stroke, cognitive disorders, and depression in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(6):371–380. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carnethon MR, Gulati M, Greenland P. Prevalence and cardiovascular disease correlates of low cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2005;294(23):2981–2988. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K, et al. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. JAMA. 2004;292(18):2237–2242. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, et al. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284(5):592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunnar M, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galobardes B, Smith GD, Lynch JW. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, et al. Association between children’s experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1640–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner E, Davey Smith G, Marmot M, Canner R, Beksinska M, O’Brien J. Childhood social circumstances and psychosocial and behavioural factors as determinants of plasma fibrinogen. Lancet. 1996;347(9007):1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(2):330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(4):1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas C, Hyppönen E, Power C. Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1240–e1249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cacioppo JT, Patrick W. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. New York, NY: W W Norton & Co Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shonkoff JP, Phillips D, editors. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caspi A, Harrington H, Moffitt TE, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Socially isolated children-20 years later: risk of cardiovascular disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(8):805–811. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, Carmona RH. The family history—more important than ever. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(22):2333–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;2(8663):577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(23):2329–2337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Caspi A, et al. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):651–660. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz KK, Compton W. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St Louis, MO: Washington University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107(3):499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elley WB, Irving JC. Revised socio-economic index for New Zealand. N Z J Educ Stud. 1976;11:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asher SR, Paquette JA. Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, Olfson M. Brief screening for family psychiatric history: the Family History Screen. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):675–682. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higgins M, Province M, Heiss G, et al. NHLBI Family Heart Study: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(12):1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis P, Jenkin G, Coope P. New Zealand Socio-economic Index 1996: An Update and Revision of the New Zealand Socio-economic Index of Occupational Status. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9) suppl:S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, et al. Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adler NE, Boyce WT, Chesney MA, Folkman S, Syme SL. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: no easy solution. JAMA. 1993;269(24):3140–3145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Family poverty, welfare reform, and child development. Child Dev. 2000;71(1):188–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278(8):637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bierman KL, et al. Peer Rejection: Developmental Processes and Intervention Strategies. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levine S, Alpert M, Lewis GW. Infantile experience and the maturation of the pituitary adrenal axis. Science. 1957;126(3287):1347. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3287.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solomon GF, Levine S, Kraft JK. Early experience and immunity. Nature. 1968;220(5169):821–822. doi: 10.1038/220821a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coe CL, Lubach GR, Ershler WB, Klopp RG. Influence of early rearing on lymphocyte proliferation responses in juvenile rhesus monkeys. Brain Behav Immun. 1989;3(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suomi SJ. Early determinants of behaviour: evidence from primate studies. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(1):170–184. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. NEngl J Med. 1998;338(3):171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4770–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081072698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker EA, Unutzer J, Rutter C, et al. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):609–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Enos WF, Holmes RH, Beyer J. Coronary disease among United States soldiers killed in action in Korea: preliminary report. JAMA. 1953;152(12):1090–1093. doi: 10.1001/jama.1953.03690120006002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]