Abstract

Advances in HIV treatment and opportunistic illness prophylaxis have significantly extended the life expectancy of people living with HIV/AIDS. Increased HIV/AIDS longevity is also marked by changes in HIV transmission risk behaviors. Here we review the literature on HIV transmission risk behaviors as they change in relation to stages of HIV disease among persons who are infected with HIV/AIDS. Studies confirm that the time period immediately preceding testing HIV positive is characterized by high risk behaviors indicating the potential for rapid spread of HIV during acute infection. For many people, reductions in risk behavior are seen immediately following HIV diagnosis. However, these changes in risk taking are not universal and great variability exists in terms of how HIV diagnosis influences risk behaviors. Chronic periods of asymptomatic HIV infection are generally associated with some degree of reverting to high risk behaviors. Also, a CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3 resulting in a formal diagnosis of AIDS, is associated with decreased sexual and drug-related risk behaviors. HIV risk reduction interventions that target men and women living with HIV/AIDS therefore require tailoring to stages of HIV disease. Additional research on risk behaviors of long term HIV positive persons is needed.

The meaning of an HIV diagnosis has changed substantially since the early years of the AIDS crisis. Initially, supportive and palliative care were the only options for people who tested HIV positive. However, with advances in antiretroviral therapies and prophylaxis against opportunistic illnesses, AIDS defining conditions have decreased significantly, and life span expectancies among people living with HIV/AIDS have lengthened. Antiretroviral treatment side effects have generally been viewed by people living with HIV/AIDS as an acceptable tradeoff for treatment benefits, particularly decreased HIV related symptoms and increased longevity (Liu, Johnson, Ostrow et al., 2006). These improvements in quality of life resulting from HIV treatments have been identified in multiple domains including physical, mental, and social functioning.

Advances in HIV treatments have led to a general optimism about the quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS (Parsons, Braaten, Hall et al., 2006). Along with improved health among those infected with HIV there have been co-occurring changes in HIV transmission risk behaviors. For a majority of individuals, as a result of testing HIV positive risk behaviors change considerably (Weinhardt, 2005). However, what is not clear is how risk behavior evolves over the course of living with HIV. Since the HIV disease process unfolds over a growing length of time it is important to consider how different stages of disease can affect risk behavior. Moreover, individuals may be diagnosed with HIV at any stage of HIV infection: acute infection, chronic and asymptomatic stages, symptomatic infection, and end stage disease. The clinical stages of HIV infection reflect the state of the immune system which is most commonly indexed by the number of T-lymphocyte (CD4) cells (Henry, Tebas, & Lane, 2006). Therefore, stages of HIV disease are delineated by both the experience of symptomatic illness and immune system dysfunction.

With HIV positive persons living longer and healthier lives, it is increasingly important to recognize how risk behaviors change over the course of the post-HIV diagnosis life span. HIV prevention for people living with HIV/AIDS, or positive prevention, is now the US national priority in HIV prevention. As the course of HIV disease is altered by treatments and people are tested earlier, positive prevention strategies may require tailoring for stages of HIV disease.

In this paper, we review studies that have examined the association between HIV transmission risk behaviors and HIV disease stage. It is our aim to characterize the changes in risk behaviors that occur over the course of HIV infection. For the purpose of this review, we define the stages of HIV disease based on (a) duration of time since testing HIV positive and (b) clinically meaningful levels of CD4 cells.

Literature Review Procedures

Automated literature searches were performed using PubMed and GoogleScholar between August and September 2007. The searches were conducted by crossing the following key terms: HIV, life span, recently infected/diagnosed, late-stage HIV, CD4 cell count, risk behavior, long term HIV positive, stage of disease, prospective study, and cohort. Manual searches of journals and references from relevant articles were also conducted. We reviewed studies that described both (a) time since testing HIV positive, CD4 cell counts, or clinically defined stages of HIV infection, i.e., recently diagnosed, chronic HIV infection, and long term HIV positive, to index HIV disease, and (b) HIV transmission risk behavior. Studies were included when risk behaviors were operationally defined by behavioral practices such as anal or vaginal intercourse, number of sexual partners and/or injection drug use (IDU). We organized the relevant study findings according to HIV disease stage: acute or recent infection, chronic asymptomatic infection, developing symptoms/AIDS defining conditions, or CD4 counts <200, 200–500, >500; above or below 350; or CD4 as a continuous variable. Cross sectional studies were included when disease stages were specified and prospective studies were included when analyzed for changes in behavior over stages of HIV infection.

Methodological Overview of the Literature

The research examined in this review included samples with diverse HIV risk histories: heterosexual men and women, men who have sex with men (MSM), intravenous drug users (IDUs), and MSM/IDUs. Studies also varied in their design such that prospective cohorts, cross-sectional studies, and pre/post diagnosis designs were included. Recently diagnosed HIV positive persons were defined by all studies as those who have been diagnosed less than 12 months. Long term HIV infection was defined by individuals who were aware of their HIV infection for at least 8 years. Results based on different definitions of disease stage were therefore examined separately because they are interpreted differently. Studies included in this review had to provide information on both HIV transmission risk behavior and stage of disease. The inclusion of disease stage and risk behavior in an article did not necessarily need to be the major focus of an article, but certainly needed to be present. Date of publication not did exceed past ten years and included up to July 2007. Studies were limited to the US with the exception of one London based study. Adolescents were not included in this review.

Overall, we identified 154 peer reviewed research articles as having the potential to provide information on risk behaviors over the course of HIV disease. From these articles we were able to identify 15 studies with data linking risk behaviors to markers of disease stage among HIV positive persons. These articles were separated into prospective/cohort studies of long term HIV positive persons (n = 3), CD4 related studies (n = 7), and recently infected/diagnosed studies (n = 5). In total, data from 9,713 HIV positive persons were reported across studies, of which 3,602 (37%) participants were MSM, 871 (9%) were women, 299 (3%) were IDUs, and 4,941 (51%) were either MSM, heterosexual women, or heterosexual men with HIV.

HIV Transmission Risk Behavior Changes Over the Course of HIV Infection

Recently infected with HIV

As expected, people recently infected with HIV demonstrate considerable risk behavior (Table 1). Most recently infected MSM report repeated engagement in high risk sexual behaviors. A vast majority of these men report unprotected anal intercourse with their most recent sexual partners (Drumright et al., 2006). Recent infection is also a period in which many MSM engage in unprotected sexual acts with more than one partner. High rates of risk behavior with multiple sexual partners therefore occur during acute infection, when HIV transmission risks are greatest, and the person is least likely to be aware that they are HIV infected. Drumright et al. (2006) reports a median of 20 sexual partners within the past year in people who have been recently diagnosed. Although acute infection is clearly a time of higher HIV transmission risk, it is estimated that no more than 18% of sexually transmitted HIV infections in the US occur during the acute infection period, indicating continued risks of transmitting HIV throughout infection (Pinkerton, 2007).

Table 1.

Stage of disease and risk behaviors among HIV positive persons.

| Authors, Date | Risk Group | Design | Stage | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colfax (2002) | 66 MSM | 12 month prospective cohort | Seroconversion and acute infection | Men reported substantial risk at the time of seroconversion and significant risk reduction after notification of HIV infection. Risk behavior increased over the 12 month observation for a significant minority of men. |

| Drumright (2006) | 116 MSM | Acute Infection and Early Disease Research Program (AIEDRP) cohort | Recently infected | 84% reported unprotected anal intercourse with at least some of their last three sex partners. 20.5 median number of partners for past 12 months and 4 median number of partners for past 3 months. |

| Smith (2005) | 194 MSM | Cohort study of Internet users | Recently diagnosed (<12 months) | Participants who used the Internet to find sex partners reported more male sex partners in past three months (11.1 vs. 5.7), were more likely to report no main sexual partners (62.7% vs. 39.7%) and were more likely to report sexual contact with past three partners (34.9% vs. 14.7%). Although risk behavior tends to decrease after diagnosis, those who use the Internet display continued risk behaviors. |

| CDC (2001) | 180 women and men | Interviewed about behavior pre and post diagnosis | Recently diagnosed (<12 months) | 90% reported behavior change since diagnosis. 60% used condoms more often, 49% did not have sex as often, and 36% had not had sex since diagnosis. |

| Gorbach (2006) | 113 MSM | AIEDRP | Recently diagnosed (<12 months) | 3 months post-diagnosis, 47% reported a decrease in partners, 34% reported similar numbers, and 20% reported an increase. Unprotected anal intercourse with last partner was same at baseline and 3M follow up (59%) |

| Macalino (2003) | 871 women | HERS (HIV Epidemiology Research Study) | <200, 200–500, and >500 CD4 cell counts. | HIV positive women with CD4 <200 were less likely to report injecting drug use than HIV positive women with CD4 counts ≥ 200. No differences between 200–500 and >500. |

| Dolezal (1999) | 86 male IDU | Natural history study | <200, 200–500, and >500 CD4 cell counts. | Participants with CD4<200 and participants with >1 HIV symptom were more likely to report no sexual partners. No differences between 200–500 and >500. |

| Dukers (2001) | 1,062 MSM | Ecological study of time trends. Amsterdam cohort study between 1992–2000 | Above or below 350 CD4 cell count. | CD4 cell counts ≥350 (no HAART) and rising CD4 cell counts after HAART was associated with greater likelihood of unprotected sex with casual partner. |

| Morin (2005) | 1910 MSM | Computer administered survey at multiple US sites. Healthy Living Project Team | CD4 cell count was dichotomized as <200 or ≥200. | CD4 cell count was not predictive of risky sex with steady or casual partners. |

| Kalichman (2005) | 141 MSM | Cross-sectional survey | CD4 cell count analyzed as continuous variable | Among MSM who use the Internet, MSM who sought sex partners online had higher CD4 cell counts (498 vs. 355). |

| Tun (2001) | 190 IDU | Cohort study, AIDS Link to Intravenous Experiences (ALIVE). | CD4 cell count analyzed as continuous variable | Participants with increased CD4 cell count after HAART initiation as opposed to participants with no increase were more likely to report unprotected sex. |

| Bachman (2005) | 338 MSM and heterosexual men | Cross- sectional surveys, HIV clinic | CD4 cell count analyzed as continuous variable | Participants with higher CD4 cell counts were more likely to engage in unprotected anal intercourse. Likelihood of engaging in unprotected anal intercourse increased 20% for every 100 unit increase in CD4 cell count. |

| Weinhardt (2005) | 3723 women and men | Cross- sectional data arrayed by months living with HIV/AIDS. | Time since diagnosis spanning less than 3 months to over 6 years | HIV transmission risk behaviors were highest prior to HIV diagnosis with declines among those recently diagnosed. Risk behaviors remained relatively stable past one year after diagnosis, with 15% to 40% of people living with HIV reporting transmission risk behavior at any given time. |

| McCoy (2005) | 23 IDU | Cohort study between 1989–1998 | Long term HIV positive individuals | 43% of the sample decreased their injection drug use over the course of the study. 91% of the sample reported crack use in 1989 and 1998. 52% reported no condom use at either time points, 41% increased condom use over course of study. |

| Aidala (2006) | 700 women and men | Prospective cohort study, interviews every 6–12 months, 1994–2002 | Long term HIV positive individuals | Unprotected sex was highest in 1996, reached a low in 2000, and increased at most recent interviews: MSM (23%, 10%, 11%), heterosexual men (9%, 4%, 8%), and women (10%, 5%, 11%). |

Recently Diagnosed with HIV

Following HIV diagnosis significant numbers of HIV positive individuals reduce their sexual risk behaviors (Marks, Crepaz, Senterfit et al., 2001; CDC, 2001). Although immediate reductions in risk behaviors are clearly encouraging from a prevention perspective, it is apparent that for some heterosexual men and women, and MSM high risk behavior continues after HIV diagnosis (CDC, 2001; Gorbach, Drumright, Daar et al., 2006). Colfax et al. (2002) followed a cohort of MSM who seroconverted to HIV and found substantial reductions in high risk behaviors immediately following notification of their HIV positive status. However, reductions in risk behavior were short lived for some men who reverted to HIV transmission risks within one year of testing HIV positive. For example, one study reported that 34% of recently HIV diagnosed MSM did not change their risk behavior and 20% actually increased their risk behavior after diagnosis (Gorbach et al., 2006). The behavioral effects of an HIV positive diagnosis appears to be highly variable across individuals with condom use, numbers of partners, and rates of risk behaviors following diagnosis decreasing for some and increasing for others. Weinhardt (2005) found that the proportion of people living with HIV who were engaging in unprotected intercourse after the first year of diagnosis remained relatively stable between 20% and 30% of the sample. Importantly, within the same study, increases in risk behaviors were still considerably lower than levels of risk behaviors observed prior to HIV diagnosis. This finding suggests that some individuals newly diagnosed with HIV experience difficulty reducing risk behaviors as they adjust to an HIV positive diagnosis over the first year. Thus, in the years following diagnosis there remains a relatively stable minority of individuals who continue to engage in HIV transmission risk behavior.

Chronic HIV infection

Reductions in CD4 cell counts are the hallmark of advancing HIV infection. Overall, studies show that decreases in CD4 cell counts predict decreases in sexual risk behaviors. Reductions in sexual risk behavior are most pronounced among individuals who have CD4 cell counts below 200 cells/mm3 (Dolezal et al., 1999). Both numbers of sexual partners and rates of unprotected sexual acts decrease during the later stages of chronic infection. Conversely, no differences in sexual risk behavior are observed among persons with CD4 cell counts between 200–500 cells/mm3, representing immune system decline, and those with CD4 cell counts greater than 500 cells/mm3, representing a more functional immune system. Among untreated persons with less than 350 cells/mm3, decreases in unprotected sexual acts with casual partners are more likely to be reported than decreases with regular partners. Additionally, increases in CD4 cell counts after receipt of antiretroviral therapy are associated with increased unprotected sexual acts with casual partners (Dukers et al., 2001).

When CD4 cell counts are analyzed as a continuous variable, studies suggest a linear relationship between CD4 counts and risk behaviors; as CD4 cell counts decline risk behaviors decline as well (Bachman et al., 2005). Importantly, among women and men who receive antiretroviral therapy, only those with increased CD4 cell counts demonstrate increased sexual risk behavior (Tun, Gange, Vlahov et al., 2001). Moreover, incremental increases in CD4 cell counts and overall higher CD4 cell counts are associated with increases in unprotected anal sex among MSM (Bachman et al., 2005; Kalichman, Cherry, Cain et al., 2005).

Studies of female injection drug users show that having a CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3, representing severe immune system dysfunction, is associated with decreases in intravenous drug use (Macalino et al., 2003). For these same individuals decreases in sexual risk behaviors are also observed. However, no differences in intravenous drug use are found between individuals with moderate CD4 cell counts of 200–500 cells/mm3 versus those with more functional immunity of greater than 500 cells/mm3. This finding suggests that at least among women the relationship observed between decreases in CD4 cell counts and sexual practices holds true for drug use behaviors as well.

Late stage HIV Infection

Few studies have examined HIV risk behavior during the later stages of HIV infection and AIDS. However, some studies have identified women and men with long term HIV infection as showing a decrease in their risk behaviors. McCoy et al. (2005) reported that many individuals who injected drugs in the late 1980s did not continue this behavior into the late 1990s. Notably, the rate at which HIV positive persons shared needles also declined significantly from 43% in 1988 to 8% in 1998. When compared with uninfected persons and those who seroconverted during the course of the study, HIV positive persons demonstrated the largest increase in condom use. However, half of all HIV positive persons reported no condom use.

Long-Term Perspectives

Only a few studies have examined changes in HIV transmission risk behavior over extended periods of time. However, Weinhardt (2005; see also Morin et al., 2005) examined sexual risk behaviors among 3,723 persons at different durations of time since receiving an HIV positive diagnosis. This research showed that risk behaviors decline in the months that follow receiving an HIV positive diagnosis and remain fairly low following diagnosis with some increases in risk behaviors occurring over subsequent months and years. Furthermore, trends in sexual risk behavior from an additional prospective cohort study of HIV positive women and men showed decreases in unprotected sex acts over a six year period (Aidala, Lee, Garbers, & Chiasson, 2006). However, this trend reversed slightly toward the end of the study with increases in unprotected sex acts observed during the final year of observation. Women reported a high of 24% unprotected sex in the earlier years to a low of 9% during the middle years with a slight increase to 10% in the last year. Heterosexual men reported a high of 8% unprotected sex in the earlier years to a low of 3% in the middle years and then increased to 6% during the last year. Among MSM, 9% reported unprotected sex early on, increased to 11%, then ultimately dropped to 5% in the middle years followed by an increase to 11% during the last year. Many men and women were not sexually active for substantial periods of time whereas others maintained multiple sex partners for long periods. Risk behavior alternated with periods of safer behavior over time. Fluctuations in risk behavior were associated with several factors including age (younger persons reported more periods of risk behavior), times of homelessness among women, and substance use.

Summary of Risk for HIV Transmission and Stage of Disease

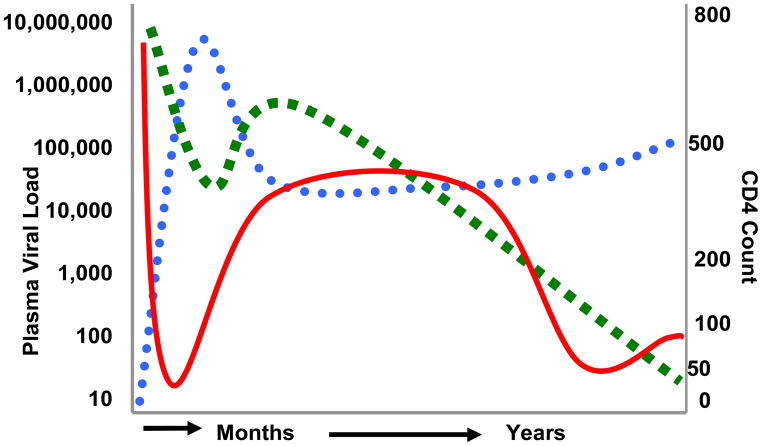

Figure 1 shows the general model of changes in CD4 cell counts and viral load over the years of HIV infection. During the first months following exposure to HIV, defined as the acute infection stage, CD4 cells decline rapidly as HIV replicates at high rates. Subsequently, viral replication slows and CD4 cells recover, although not completely. Over the coming years and in the absence of antiretroviral therapy, HIV viral load remains steady and CD4 cells slowly decline. Near the end stage of HIV disease, viremia increases and CD4 cells are further depleted. As shown in the figure, we have superimposed changes in transmission risk behaviors over time as derived from the literature review. Risk behavior rapidly declines following diagnosis and returns to higher, although not baseline, levels over time. When CD4 cells reach less than 200 cells/mm3 and symptoms appear, risk behavior again declines with a potential of slight resurgence in later stage disease. The three HIV infection processes (viral replication, CD4 cell depletion, and risk behavior change) depicted in the model are represented without the inclusion of potential medical or behavioral intervention effects.

Figure 1.

Model of HIV disease progression in relation to HIV transmission risk behaviors. The dotted line represents HIV viral load, the dashed line represents CD4 cell counts, and the solid line represents HIV transmission risk behaviors.

Implications of stage of disease, risk behavior, and HIV transmission risks

The stages of HIV disease were also accompanied by different degrees of infectiousness. In terms of HIV concentrations in blood, the period of initial infection or acute infection has been identified as a time in which HIV infectiousness is at its highest and substantial risk behavior is reported as well. Later stage disease, such as during symptomatic periods, has also been associated with elevated HIV viral loads and therefore greater infectiousness (Rapatski, Suppe, & Yorke, 2005). However, blood viral load and genital tract viral load do not have a one-to-one correspondence. HIV concentrations are typically lower in genital tract secretions than in blood, but there are factors that reverse this pattern. In particular, spikes in HIV viral shedding occur with genital tract inflammation, especially when the problem is the result of sexually transmitted infections (STI; Kalichman, DiBerto, & Eaton, 2008). In addition, in a review of the literature, changes in viral load were found to be associated with risk behavior practices when individuals believe that having an undetectable viral load leads to lower infectiousness (Crepaz, Hart, & Marks, 2004). Thus, individuals who have low-levels of blood viral load and believe they are less infectious may increase their risk behaviors. They are unwittingly exposing themselves to STI resulting in greater infectiousness without increases in awareness of infectiousness.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Changes in risk behaviors emerge as people living with HIV/AIDS progress through the stages of HIV disease. Stages of HIV disease are marked by changes in physical functioning and quality of life. Initially, for most people, HIV risk behaviors decrease after becoming aware of their HIV infection and this decline in risk behavior may last for as long as one year after diagnosis or longer. About two out of five MSM, who become HIV positive, will continue to engage in high risk behaviors following notification of HIV infection (van Kesteren, Hospers, & Kok, 2007). Risk behaviors re-emerge over subsequent years of living with HIV, especially during asymptomatic periods. Throughout the course of HIV infection, risk behaviors related to both sex and injection drug use appear to decrease; however resurgence is possible during later stage disease. Reductions in risk behaviors are therefore related to both passage of time and decline in health. For long term HIV infection, risk behaviors decrease after a considerable time period has passed and CD4 cells fall below 200 cells/mm3. Although voluntary counseling and testing does have a beneficial impact on reducing the risk behaviors of most recently HIV diagnosed individuals there is still great need to intervene with individuals who continue to engage in high risk behaviors.

Based on the current review we have identified the need for further reporting on data relevant to risk behaviors of individuals who have been living long term with HIV. Although data on recently infected/diagnosed persons are aptly reported on, other stages of HIV disease are much less likely to be reported on. Ironically, it is well recognized that individuals are living longer with HIV (Gross, 2008), however, the literature, at least when considering risk behavior, doesn’t appear to emphasize later stages of HIV disease. Addressing this concern should not prove to be particularly burdensome either; asking and reporting on time since HIV diagnosis and providing subsequent risk behavior data would provide important information for garnering a better understanding of the needs of this population.

Given the medical focus of clinical care and available resources, health professionals who work with HIV positive individuals have limited time to address risk behaviors. However, having a prior understanding of risk behaviors as they relate to stages of disease can help in assisting health professionals when discussing these issues with their patients. Health professionals are in a unique position to provide information to their patients about risk behaviors, thus, their patients could potentially benefit from providers who are informed about how risk behaviors change.

Findings from this review suggest that HIV risk reduction interventions targeted to people living with HIV infection should be tailored to HIV disease stages. Individuals who are diagnosed with HIV soon after they are infected, namely acute or recently infected persons, will require attention to their immediate psychosocial and medical needs. Transmission risk reduction at this stage may focus on assisting patients to manage decisions regarding disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and injection partners as well as to develop skills for immediately commencing safer practices. Individuals with later stage disease who demonstrate a decline in health may experience bouts of depression, which can be related to HIV transmission risk behaviors. Individuals with intermediate CD4 cell counts may be dealing with treatment decisions, health uncertainties, and other health-related stressors. Interventions for these individuals should address HIV treatment beliefs, treatment decisions, adaptive coping, and sexual decisions.

Although studies have investigated how risk behaviors change with HIV disease stage, there are still additional areas that need further investigation. Primarily, it is not clear what is driving the relationship between CD4 cell count decline and risk behavior decline. This relationship may exist because of poor health or the psychological impact of a worsening immune system; however, in either case further research is needed to answer why decreasing CD4 counts result in a subsequent drop in risk behavior. Finally, why some people who initially decrease their risk behaviors following diagnosis ultimately rebound warrants further investigation. Identifying similarities and differences among those who display risk for HIV transmission following diagnosis versus those who do not display such behaviors may shed light on how to better intervene with persons engaging in risk behaviors.

Additional research is needed to determine the causal paths of HIV disease progression and risk behaviors. It appears that declines in health, diagnosis of HIV, and diagnosis of AIDS all precede decreases in risk behaviors. Knowing how risk behaviors change over the course of HIV infection will improve targeting the groups in greatest need for interventions and building the most relevant skills for managing HIV transmission-related behaviors.

From our review we identify the following clinical considerations for HIV prevention with HIV positive patients.

When delivering information pertaining to an HIV positive individual’s clinical health, behavioral risk reduction messages can also be addressed during this time period. These messages can be tailored to the individual based, in part, on stage of HIV disease.

Particular attention should be given to recently diagnosed and chronic stage HIV positive persons to ensure that risk behaviors do not rebound to pre HIV diagnosis levels. Risk reduction includes assessing current risk behavior and providing behavioral risk reduction counseling.

Aggressive monitoring and treatment of STI is a critical feature of HIV clinical care that can profoundly reduce HIV transmission risks. STI causes genital shedding of HIV and increased infectiousness. Detecting and treating STI in people living with HIV must be fully integrated with HIV clinical care.

Addressing issues of decreased immune system functioning and sexual behaviors appear to be of considerable importance for late stage HIV positive persons. HIV positive patients will benefit from these needs being discussed during clinical care. Depression treatment, including support groups, should be emphasized to both enhance quality of life and prevent HIV transmission risks.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01-MH71164 with supplemental funding from the National Institutes of Health Office of AIDS Research and grant T32- MH074387.

References

- Aidala AA, Lee G, Garbers S, Chiasson MA. Sexual behaviors and sexual risk in a prospective cohort of HIV-positive men and women in New York City, 1994–2002: Implications for prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18:12–32. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman LH, Grimley DM, Waithaka Y, Desmond R, Saag MS, Hook EW. Sexually transmitted disease/HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted disease prevalence among HIV-positive men receiving continuing care. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:20–6. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148293.81774.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Hays RD, Jacobson LP, Chen B, Gange SJ, Kass NE, et al. Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: Results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1008919227665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Adoption of protective behaviors among persons with recent HIV infection and diagnosis—Alabama, New Jersey, and Tennessee, 1997–1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2001;49:512–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Buchbinder S, Cornelisse P, Vittingoff E, Mayer K, Celum C. Sexual risk behaviors and implications for secondary transmission during and after HIV seroconversion. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002;16:1529–35. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:224–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal C, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Liu X, Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Rabkin J, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual risk behavior among HIV+ and HIV − male injecting drug users. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:281–303. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MRG, Malcarne VL, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:344–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukers NH, Goudsmit J, de Wit JBF, Prins M, Weverling GJ, Coutinho RA. Sexual risk behavior relates to the virological and immunological improvements during highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2001;15:369–78. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Drumright LN, Daar ES, Little SJ. Transmission behaviors of recently HIV infected men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42:80–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000196665.78497.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross . The New York Times. Jan 6, 2008. AIDS patients face downside of living longer. [Google Scholar]

- Henry WK, Tebas P, Lane HC. Explaining, predicting, and treating HIV-associated CD4 cell loss: After 25 years still a puzzle. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:1523–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.12.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, DiBerto G, Eaton LA. Associations among HIV concentration in blood plasma and semen: Review and implications of empirical findings. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35:55–60. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e318141fe9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Cain D, Pope H, Kalichman M. Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of seeking sex partners on the Internet among HIV-positive men. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:243–50. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Johnson L, Ostrow D, Silvestre A, Visscher B, Jacobson LP. Predictors of quality of life in the HAART era among HIV-infected men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42:470–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225730.79610.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macalino GE, Ko H, Celentano DD, Hogan JW, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, et al. Drug use patterns over time among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women: The HER Study Experience. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:500–5. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy CB, Metsch LR, Comerford M, Zhao W, Coltes AJ, Messiah SE. Trends of HIV risk behaviors in a cohort of injecting drug users and their sex partners in Miami, Florida, 1988–1998. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:187–99. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Steward WT, Charlebois ED, Remien RH, Pinkerton SD, Johnson MO, et al. Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: Findings from the Healthy Living Project Team. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;40:226–35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000166375.16222.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons TD, Braaten AJ, Hall CD, Robertson KR. Better quality of life with neuropsychological improvement of HAART. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton SD. How many sexually-acquired HIV infections in the USA are due to acute-phase HIV transmission? Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;21:1625–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32826fb6a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapatski BL, Suppe F, Yorke JA. HIV epidemics driven by late disease stage transmission. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38:241–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun W, Gange SJ, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. Increase in sexual risk behavior associated with immunologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;38:1167–74. doi: 10.1086/383033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kesteren NMC, Hospers HJ, Kok G. Sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: A literature review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;65:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt L. HIV diagnosis and risk behavior. In: Kalichman SC, editor. Positive Prevention: Reducing HIV Transmission among People Living with HIV/AIDS. Springer Science; New York: 2005. pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]