Abstract

Background: Fetal transplantation for Parkinson disease (PD) had been considered a promising therapeutic strategy; however, reports of Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites (LNs) in engrafted tissue adds to controversy surrounding this treatment for PD. Methods: The brain of a PD patient who had fetal transplantation 14 years before death was evaluated. The graft was studied with routine histologic methods, as well as immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein, neurofilament, synaptophysin and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), as well as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) for astrocytes and ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1) for microglia. Results: On coronal sections of the brain, the graft extended from the putamen to the amygdala, abutting the anterior hippocampus. Microscopically, the graft consisted of neuron-rich and glia-rich portions. Neuron-rich portions, resembling a neuronal heterotopia, were located in the putamen, whereas the glia-rich portion was more ventral near the amygdala. LBs and LNs were detected in the ventral portion of the graft, especially that part of the graft within the amygdala. Areas with LBs and LNs also had astrogliosis and microgliosis. TH positive neurons were rare and their distribution did not overlap with LBs or LNs. Comments: LBs and LNs were detected in the transplanted tissue with α-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Unexpected outgrowth of the graft into the amygdala was accompanied by skewed distribution of LBs and gliosis, more abundant in the graft within the amygdala. The distribution of LBs within the graft may suggest the potential role of the local environment as well as gliosis in formation of α-synuclein pathology.

Keywords: Fetal transplantation, Parkinson disease (PD), therapy, α-synuclein pathology, gliosis

Introduction

Although the pathology of Parkinson disease (PD) is not limited to the substantia nigra (SN), the motor symptoms of PD are largely caused by the dopaminergic (DA) cell loss of the SN with the resultant dopaminergic denervation of the striatum. Fetal transplantation for PD patients had been considered as one of the promising strategies for dopamine replacement in spite of the ethical issues until two large controlled clinical trials showed its lack of efficacy with some patients suffering from severe “off-medication” dyskinesia as a serious side-effect [1,2].

Apart from the lack of clinical efficacy and “off-medication” dyskinesia, recent studies on the long-term fate of the grafts raised more serious questions about transplantation therapy in PD. Recent pathologic reports on fetal grafts 11-16 years after transplantation showed that abnormal α-synuclein inclusions were present in the grafts [3-7]. An initial contradictory report was reversed in the later studies [8,9]. In one of these patients, the clinical course eventually deteriorated in spite of initial improvement by the transplant. Although functional significance of α-synuclein pathology in the graft can be debated, the presence of α-synuclein inclusions in the grafts suggests the disease has “spread” from of the host to the graft [7,10,11].

In this study, we examined a patient with PD who had received a fetal mesencephalic transplant 14 years before autopsy in which α-synuclein pathology was detected. Autopsy was performed at The Parkinson Institute with written consent of the legal next-of-kin and neuropathologic evaluation was performed at Mayo Clinic Jacksonville using procedures approved by the institutional review board as part of research on the neuropathology of neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and methods

Case history

A right-handed man first noted a loss of sense of smell and taste in 1973 at age 38. Sixteen years later, at age 54, he developed rest tremor in the right hand. Over the next two years, the tremor worsened, and he experienced a decline in volume of speech, smaller handwriting, and difficulty using utensils and buttoning clothes. Neurologic evaluation at the age 56 revealed a mild loss of facial expression, a low-amplitude resting tremor and loss of fine coordination in the right hand. Tone was moderately increased on the right. MRI of the head was reportedly normal. There was a history of parkinsonism and dementia in his mother and “balance problems” in his maternal grandmother.

The patient was treated with selegiline and low doses of levodopa/carbidopa a few months later. Over the next several years, with increasing doses of levodopa, he developed motor fluctuations, generalized dyskinesias, intermittent limb dystonia and gait impairment that limited his functional capacity. In December 1994, the patient decided to undergo ventral mesencephalic fetal tissue transplantation at a hospital in southern California. Mesencephalic tissue from 6-8-week-old aborted fetuses was surgically placed in the posterior putamen bilaterally. Post-operatively he was placed on immunosuppressive therapy (cyclosporin evolved over the next 6 months, he decided toe and prednisone). Owing to auditory and visual hallucinations, generalized weakness and night terrors that stop all of his medications in mid-1995.

An MRI at that time showed bilateral foci of increased signal intensity in the region of transplants, surrounding the extreme capsule and posterior limb of the internal capsule. A minimal mass effect was noted in the area of the right cerebellopontine angle above the 7th and 8th cranial nerves. Three subsequent scans showed essentially no significant changes.

Over the next several years, the patient experienced increasing problems with drooling and speech. Because of episodes of freezing and falling, in March of 2002 he underwent bilateral deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery. His wife reported that the tremors and freezing episodes disappeared after DBS, but over the next six years, he began experiencing cognitive decline, as well as increasing difficulties with swallowing and frequent choking spells. He died of aspiration while eating in January of 2008 at the age of 72.

Brain tissues

The fixed right hemibrain was received for evaluation. It was sliced in a coronal plane and sections taken for histology, after embedding in paraffin. The following regions were examined: 6 regions of the cortex (middle frontal, superior temporal, inferior parietal, pre-and post-central gyri, anterior cingulate gyrus, occipital pole including visual cortex), anterior and posterior hippocampus, amygdala with basal forebrain and hypothalamus, basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum. Additional sections were taken to show the entire dorsoventral extent of the graft in the basal ganglia, temporal stem and dorsal amygdala.

Histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis

Sections were cut at 5-μm thickness, mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin as well as thioflavin-S. Sections of cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, basal ganglia, as well as midbrain, pons and medulla were immunostained with a polyclonal antibody to α-synuclein [12] using a DAKO Autostainer and Envision reagents with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Other antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are summarized in Table 1. A Luxol fast blue/periodic acid Schiff stain (LFB) was used for the evaluation of myelination.

Table 1.

List of antibodies

| Antigen | Antibody | Type | Dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | GFAP | mouse | 1:10000 | Biogenex |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | GFAP | rabbit | 1:2500 | Biogenex |

| Glutamic acid decarboxylase | GAD | rabbit | 1:250 | Chemicon |

| IBA-1 | IBA-1 | rabbit | 1:2000 | Wako Chemicals |

| Neurofilament SMI | 31 | mouse | 1:20000 | Sternberger |

| SNAP-25 SP | 12 | mouse | 1:1000 | Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY |

| Tyrosine hydroxylase | TH | rabbit | 1:600 | Affinity Bioreagents |

| α-Synuclein | LB509 | mouse | 1:100 | Zymed |

| α-Synuclein | NACP | rabbit | 1:3000 | Mayo Clinic Jacksonville |

Results

Macroscopic findings

The calculated whole brain weight based upon doubling the weight of the fixed right hemibrain was within normal limits, 1240 grams. There was mild cortical atrophy over the frontal convexity. There was a small softening in the premotor cortex in the parasagittal region that corresponded to the DBS tract, which could be traced to small cavitary lesions in the periventricular white matter, internal capsule and lateral thalamus. Horizontal sections of the midbrain, pons and medulla at right angles to the neuraxis were unremarkable, except for decreased pigmentation in the substantia nigra (SN) and the locus ceruleus (LC). The cerebellar sections showed no unusual features.

The graft was a firm white lesion, which measured 2.0 x 0.7 x 2.5-cm, centered in the putamen. The margins were ill defined and lobulated. Within the firm area, there were several small cysts. The lesion was present at multiple levels of the putamen, beginning at the level of the nucleus accumbens and extending as far back as level of the subthalamic nucleus. It was centered in the lateral putamen, but also extended into the temporal stem and the dorsolateral amygdala. The anterior hippocampus was displaced by the lesion.

Microscopic findings of the host brain

A cystic lesion in the frontal white matter consistent with a surgical tract related to the past history of DBS had gliosis and myelin rarefaction. At the end of the trajectory was a focus of gliosis in the ventrolateral thalamus, dorsal to the subthalamic nucleus.

A few cortical Lewy bodies (LBs) were detected in the lower cortical layers, most numerous in limbic and paralimbic cortices, including anterior cingulate gyrus and the parahippocampal gyrus. LBs and Lewy neurites (LNs) were also numerous in the basal forebrain, hypothalamus and amygdala. Sparse neurites and a few glial inclusions were noted in the putamen and a few axonal spheroids were detected in the globus pallidus with α-synuclein immunohistochemistry. There was moderate-to-marked neuronal loss with LBs and LNs in the SN, the LC and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. The distribution of α-synuclein pathology was consistent with transitional (limbic) Lewy body disease.

Alzheimer pathology was minimal, with neurofibrillary tangles limited to the medial temporal lobe (Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage II) and no cortical senile plaques in any cortical or subcortical section.

Microscopic findings of the fetal neural transplant

The transplanted tissue was present in the lateral putamen, but also extended into the amygdala. It had a multinodular and focally cystic appearance and was demarcated from the host tissue (Figure 1). Microscopically, the cysts had a smooth lining that resembled a glia limitans and were superficially similar to arachnoid cysts. The graft was clearly differentiated from the host tissue by GFAP immunohistochemistry (Figure 2A). The graft was characterized by paucity of lipofuscin pigment within neurons and lack of myelinated fibers that were present in the adjacent putamen (Figure 3A, B). There was also a paucity of age-related ubiquitin immunoreactive pathology, such as granular degeneration of myelin [13], in the graft. Corpora amylacea were sparse in the graft, but relatively abundant in the interface of the graft and host tissue, especially in the graft that was adjacent to the amygdala (Figure 3C).

Figure 1.

Macroscopic appearance of graft and surrounding host tissue.

Figure 2.

A) GFAP immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 3 mm; B-1) ‘Neuronal heterotopia’ in the putaminal portion ofthe graft; Neuronal cluster (*) is surrounded by glia dominant tissue (arrowheads). Scale bar = 50 μm; B-2) Neuroma-like tissue in the amygdala portion of the graft; Only a few scattered neurons are visible among the glial cells.Scale bar = 50 μm; C-1) Rare GFAP (+) processes in the putaminal portion of the graft (‘neuronal heterotopia’) Scalebar = 50 μm; C-2) Abundant GFAP (+) processes in the amygdala portion of the graft (‘neuroma’). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 3.

A) LFB staining. Some thick bundle of myelinated fibers (arrows) seen around neuron-rich portions of graft(*). Scale bar= 300 μm; B-1) PAS (+) lipofuscin found in almost all neurons (host, amygdala); B-2) Rare smallamounts of PAS (+) lipofuscin (arrows) in a neuronal heterotopia Scale bar=50 μm; C) Corpora amylacea, yellow dots.

The graft was morphologically heterogeneous. In some areas, especially the dorsal part in the putamen, it had well differentiated neural tissue that resembled a nodular heterotropia (Figure 2B-1). In other areas, especially the ventral parts in the amygdala and at the base of the brain, the tissue was composed of neuroglial tissue resembling a neuroglioma (Figure 2B-2). The latter tissue extended around penetrating lenticulostriate arteries and grew in the subarachnoid space at the base of the brain. There were focal ependymal cell nests in these foci. The graft within the amygdala had focal dystrophic calcification.

Immunohistochemistry for GFAP showed variable staining in the graft. The neuroglial tissue had dense bundles of glial processes, while the areas that resembled nodular heterotopia had sparse astrocytes and glial processes (Figure 2C-1, C-2). The interface between the host and the graft had reactive astrocytes. Microglia were variable; they were most numerous in the neuroglial areas of the graft and less in the better differentiated nodular areas (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

IBA-1: A) IBA-1 (activated forms, red dots); B) Activated microglia in the graft. Scale bar = 50 μm.

The density of neurofilament positive cell process was variable. A few neurons were stained with a marker for phosphorylated neurofilament (SMI 31) in the graft, whereas the soma of many neurons in the amygdala was stained with SMI 31 (Figure 5). Although immunohistochemistry for synaptic proteins left some areas lightly stained, the distribution of synaptic proteins partly followed the pattern of immunostain for α -synuclein (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

SMI-31 (phosphorylated neurofilament). A) low power view of graft and surrounding tissue; B-1) area of graft with few neurons (*) Scale bar = 50 μm; B-2) area of graft with many neurons (arrowhead) Scale bar = 50 μm; B-3) host tissue (amygdala; black box). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 6.

Synaptic markers. A) SNAP25; B) α-synuclein. LBs (host and graft), blue dots.

TH immunohistochemistry showed only a few and widely dispersed medium-to-large immunoreactive neurons, some of which contained neuromelanin pigment (Figure 7). A few had diffuse α-synuclein cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, but there were no LBs. In contrast, a number of the medium-to-small neurons had cortical type LBs; there were also α-synuclein immunoreactive LNs (Figure 8A). Some LBs showed colocalization with glutamic acid decarboxylase, a marker for GABAergic interneurons (Figure 8B). Only a few glial cells contained α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions (Figure 8A, C). The density of α-synuclein pathology in the graft was variable, but greatest in the part of the graft that extended into the amygdala (Figure 6B). It was least in the well-differentiated neural tissue that resembled nodular heterotopia. It was intermediate in the neuroglial tissue, where it was mostly in the form of neuritic pathology. There were some discrepancies between immunohistochemistry with a synaptic marker, SNAP25, and α-synuclein (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

TH. A) TH positive neurons, red dots. B) TH positive neurons (* in A) Scale bar = 50 μm; C) TH positive fibers (# in A) Scale bar = 50 μm.

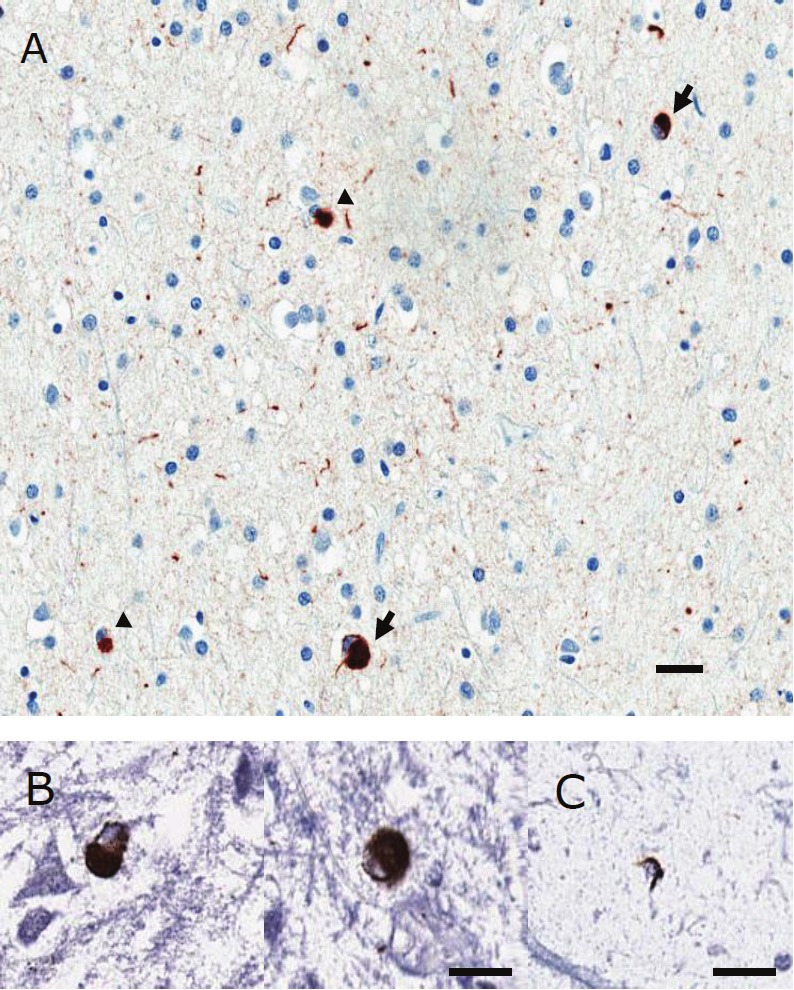

Figure 8.

A) α-synuclein: cortical type LBs (arrows)and glial inclusions (arrowheads). Scale bar = 20μm; B) Double immunohistochemistry for GAD and α-synuclein: GAD: BCIP - blue; α-synuclein: DAB - brown. Scale bar = 20 μm; C) Double immunohistochemistryfor GFAP and α-synuclein: GFAP: BCIP - blue; α-synuclein: DAB - brown. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Figure 9.

Amygdala portion of graft. A-1) SNAP25-poor area Scale bar = 50 μm; A-2) NACP in SNAP25-poor area Scalebar = 50 μm; B-1) SNAP25-rich area Scale bar = 50 μm; B-2) α-synuclein in SNAP25-rich area. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Discussion

The pathologic findings in the brain, in particular neuronal loss and LBs in the SN, are consistent with the clinical diagnosis of PD [14]. In addition to PD, there were iatrogenic processes, including glial scar tissue in the ventrolateral thalamus that is likely the result of DBS and a neuroglial lesion in the basal ganglia and amygdala that is the result of a fetal tissue transplant.

As fetal mesencephalic tissue developed α-synuclein pathology at least 10 years after transplantation, premature aging of the graft might be a contributing factor [6]. Although no surrogate marker for aging was found in a study reporting 9-14 year old grafts without α-synuclein pathology, other studies showed the presence of neuromelanin and age-related ubiquitin in the grafts [3,5]. In our patient, there were a few neurons with neuromelanin, lipofuscin and ubiquitin pathologies (Figure 3B-1, B-2). Corpora amylacea were sparse in the body of the graft, but more numerous at the periphery, especially near the amygdala (Figure 3C). Although the graft in our case was only 14 years old, these findings suggest that the graft had little evidence in support of accelerated aging; myelination was poor, age-related ubiquitin pathology and lipofuscin (autofluorescent) pigment was minimal and corpora amylacea were sparse. In addition, phosphorylation of neurofilament, a characteristic feature of neurofilaments in mature axons was lacking in the neuron-rich portions of the graft (Figure 3B-1, B-2, 5). The distribution of corpora amylacea, a surrogate marker for gliosis since they are found in cytoplasmic processes of astrocytes, was dissimilar to that of α-synuclein pathology (Figure 3C, 6C).

As α-synuclein is a synaptic protein, it was not unexpected that the distribution of SNAP-25 was partly similar to that of α-synuclein (Figure 6). In addition to some discrepancies between the distribution of SNAP25 and α-synuclein, there was no significant difference in α-synuclein pathologies between SNAP25-rich and SNAP-25-poor regions in the amygdala portion of the graft, while α-synuclein pathology was infrequent in the SNAP25-poor region in the putaminal portion of the graft (Figure 9). Therefore, synaptic maturation was not enough to explain the distribution of α-synuclein pathology.

In our patient, the density of activated microglia also showed a gradient, with less in the nodular portion of the graft in the putamen and denser in the neuroglial portion of the graft in the amygdala. This pattern was similar to the distribution of LBs (Figure 4, 6C). Thus, in view of the close relationship between activated microglia and α-synuclein pathology in the literature, microglial activation could play a role in the generation of α-synuclein pathologies [15]. However, the widespread distribution of LNs or α-synuclein immunoreactive dots in the graft could not be readily explained by the limited distribution of activated microglia.

It should be noted that our patient exhibited α-synuclein inclusions in glia as well as neurons. This is of interest, as there is an ongoing debate about the possibility of α-synuclein production by astrocytes [16-18]. An alternative hypothesis to explain glial α-synuclein inclusion is that astrocytes might take up abnormal α-synuclein secreted from the neurons [17]. However, α-synuclein pathologies were prominent even where neurons were sparse in the graft (Figure 6C). Although only a few glial inclusions were found in the graft, more active involvement of astrocytes in the production of α-synuclein could not be excluded (Figure 8).

Recent studies suggested a direct neuron-to-neuron propagation of α-synuclein in experimental models [7,19-23]. Neurons containing abnormal α-synuclein can secrete α-synuclein possibly through exocytosis, which could then be engulfed by nearby neurons [7,19-22]. The hypothetical prion-like behavior of α-synuclein might place α-synuclein pathology primarily in the periphery of the graft. However, the distribution pattern of α-synuclein pathology contradicted the expectation in our case. Moreover, α-synuclein pathology was more prominent in the neuroglial portion of the graft in the vicinity of the amygdala. The differential sensitivity of the graft to α-synuclein pathology might argue against the direct propagation model in our case.

Interestingly, in many neurodegenerative diseases, the putamen and the amygdala showed different susceptibility to pathologic processes. That is, the amygdala can be more significantly affected than the putamen by various abnormal protein aggregations, such as LBs, neurofibrillary tangles, TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions and argyrophilic grains. In contrast, the amygdala is unusually sensitive to abnormal aggregates, where lesions are found in early disease stages and disproportionate to other brain regions, including PD. Thus, the amygdala appears to be particularly vulnerable to neuronal protein aggregation abnormalities. In our study, there was a predominance of activated microglia and α-synuclein pathology in the ventral portion of the graft near the amygdala compared to the dorsal portion of the graft embedded in the putamen.

The mechanism of the preponderance of pathology in the vicinity of the amygdala remains speculative. Inflammatory signals from abundant reactive glia in the adjacent amygdala might play an important role [24]. Alternatively, unknown tissue factors contributing to the selective vulnerability of the amygdala to neurodegenerative disease could be transferred to the nearby graft. Interestingly, tissue-specific susceptibility has also been demonstrated in fetal transplantation for the patients with Huntington disease (HD), in which the grafts in the caudate nucleus could not survive, while grafts in the putamen were viable [25]. Although pathologic inclusions were not found in the fetal graft, as the caudate nucleus usually displayed most severe pathology in HD, the different pathologic outcome could be related to host tissue factors. The nature of putative transmissible tissue factors is currently unknown, it is still plausible that the fate and pathology of graft is under critical influences from neighboring tissues.

Although there was no long-term pathologic study on α-synuclein pathologies in other types of transplantation therapy, such as retinal pigment epithelial cells in PD, the “spreading” of the disease from the host could be a potential limitation of restorative therapy [10,11,26]. Further studies are needed to investigate possible tissue factors responsible for apparent spreading of pathologic processes from host to graft, apart from the emerging concept of neuron-to-neuron propagation of α-synuclein.

Acknowledgement

Supported by NIH Udall Center for Excellence in Parkinson's Disease Research (P50 NS072187) and the Robert E Jacoby Professorship for Alzheimer’s Research, as well as CurePSP, and private donations from the Dyer Fund for Movement Disorder Research and the Goldman fund for support of the brain bank at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida.

References

- 1.Olanow CW, Goetz CG, Kordower JH, Stoessl AJ, Sossi V, Brin MF, Shannon KM, Nauert GM, Perl DP, Godbold J, Freeman TB. A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:403–414. doi: 10.1002/ana.10720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, Tsai WY, DuMouchel W, Kao R, Dillon S, Winfield H, Culver S, Trojanowski JQ, Eidelberg D, Fahn S. Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:710–719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson's disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Olanow CW, Freeman TB. Transplanted dopaminergic neurons develop PD pathologic changes: a second case report. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2303–2306. doi: 10.1002/mds.22369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Bjorklund A, Widner H, Revesz T, Lindvall O, Brundin P. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson's disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med. 2008;14:501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu Y, Kordower JH. Lewy body pathology in fetal grafts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:55–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendez I, Vinuela A, Astradsson A, Mukhida K, Hallett P, Robertson H, Tierney T, Holness R, Dagher A, Trojanowski JQ, Isacson O. Dopamine neurons implanted into people with Parkinson's disease survive without pathology for 14 years. Nat Med. 2008;14:507–509. doi: 10.1038/nm1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper O, Astradsson A, Hallett P, Robertson H, Mendez I, Isacson O. Lack of functional relevance of isolated cell damage in transplants of Parkinson's disease patients. J Neurol. 2009;256(Suppl 3):310–316. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5242-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brundin P, Li JY, Holton JL, Lindvall O, Revesz T. Research in motion: the enigma of Parkinson's disease pathology spread. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nrn2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Assessing fetal nerve cell grafts in Parkinson's disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:483–485. doi: 10.1038/nm0508-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwinn-Hardy K, Mehta ND, Farrer M, Maraganore D, Muenter M, Yen SH, Hardy J, Dickson DW. Distinctive neuropathology revealed by alpha-synuclein antibodies in hereditary parkinsonism and dementia linked to chromosome 4p. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;99:663–672. doi: 10.1007/s004010051177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson DW, Wertkin A, Kress Y, Ksiezak-Reding H, Yen SH. Ubiquitin immunoreactive structures in normal human brains. Distribution and developmental aspects. Lab Invest. 1990;63:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, Duyckaerts C, Gasser T, Halliday GM, Hardy J, Leverenz JB, Del Tredici K, Wszolek ZK, Litvan I. Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson's disease: refining the diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croisier E, Moran LB, Dexter DT, Pearce RK, Graeber MB. Microglial inflammation in the parkinsonian substantia nigra: relationship to alpha-synuclein deposition. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori F, Tanji K, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K. Demonstration of alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in neuronal and glial cytoplasm in normal human brain tissue using proteinase K and formic acid pretreatment. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:98–104. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braak H, Sastre M, Del Tredici K. Development of alpha-synuclein immunoreactive astrocytes in the forebrain parallels stages of intraneuronal pathology in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:231–241. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanji K, Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Mori F, Yoshimoto M, Satoh K, Wakabayashi K. Expression of alpha-synuclein in a human glioma cell line and its up-regulation by interleukin-1beta. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1909–1912. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen C, Angot E, Bergstrom AL, Steiner JA, Pieri L, Paul G, Outeiro TF, Melki R, Kallunki P, Fog K, Li JY, Brundin P. alpha-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:715–725. doi: 10.1172/JCI43366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang A, Lee HJ, Suk JE, Jung JW, Kim KP, Lee SJ. Non-classical exocytosis of alpha-synuclein is sensitive to folding states and promoted under stress conditions. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1263–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SJ. Origins and effects of extracellular alpha-synuclein: implications in Parkinson's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;34:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HJ, Patel S, Lee SJ. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6016–6024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danzer KM, Ruf WP, Putcha P, Joyner D, Hashimoto T, Glabe C, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J. 2011;25:326–336. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halliday GM, Stevens CH. Glia: initiators and progressors of pathology in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:6–17. doi: 10.1002/mds.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cicchetti F, Saporta S, Hauser RA, Parent M, Saint-Pierre M, Sanberg PR, Li XJ, Parker JR, Chu Y, Mufson EJ, Kordower JH, Freeman TB. Neural transplants in patients with Huntington's disease undergo disease-like neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12483–12488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904239106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farag ES, Vinters HV, Bronstein J. Pathologic findings in retinal pigment epithelial cell implantation for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1095–1102. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bbff1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]