Abstract

Objectives: We reported cases of amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) without the core clinical features of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (dementia and spontaneous parkinsonism) with low uptake in 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy. Methods: During a 3-year period at a university clinic, we had 254 patients with memory complaints; 106 men, 148 women; mean age 72.5 years (48-95 years). In all patients we performed neurologic examination; memory tests including the MMSE, ADAScog, FAB and additional WMS-R; and imaging tests including brain MRI, SPECT and MIBG scintigraphy. Results: The criteria of amnestic MCI were fulfilled in 44 patients; and 13 of them (30%) showed low MIBG uptake. They had the following: uniformly elderly, with an equal sex ratio, have relatively slow progression, preserved general cognitive function (MMSE 24.8/30). In addition to memory impairment, they commonly showed low frontal function by FAB (12.5/18) and some had mild visual hallucination (5). Other than memory disorder, they had autonomic disorder (nocturia in 7, constipation in 2, postural hypotension in one), REM sleep behavioral disorder (in 3) and occipital hypoperfusion by SPECT (in 5). Conclusion: This cohort of multidomain amnestic MCI cases may present with early stage DLB because of the presence of low MIBG uptake. Clinically, they commonly have low FAB, and may have visual hallucination, autonomic and sleep disorders.

Keywords: memory disorder, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, dementia with Lewy bodies, metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy

Introduction

Early differential diagnosis of memory disorder is a challenge for neurologists. In contrast to the focus on early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1,2], little is known about early-stage memory disorder in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Recently, it is being acknowledged that DLB may produce a wide spectrum of clinical symptoms, including dementia and spontaneous parkinsonism (the core clinical features), together with depression, sleep disorder, and autonomic disorder [3,4], using imaging biomarkers indicating central dopaminergic depletion (18F-fluorodopa positron emission tomography etc.) [5] and peripheral noradrenergic depletion (123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine [MIBG] myocardial scintigraphy) [6,7]. Among these, MIBG scintigraphy is based on evidences that norepinephrine (NE) and MIBG have the same mechanisms for uptake, storage, and release [6]. There are 2 types of NE and MIBG uptake. Uptake-1 (neuronal uptake), when the concentration is low, depends on sodium and adenosine triphosphate. Uptake-2 (extraneuronal uptake), which takes place only when the concentration is high, represents simple diffusion. Delayed images are less dependent on uptake-2, and more accurately reflect cardiac sympathetic nerve activity as well as pathology [6,7]. Fujishiro et al. recently reported two cases of amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who had low MIBG uptake, without the core clinical features of DLB [8]. We had 13 cases of amnestic MCI without the core clinical features of DLB with low MIBG uptake.

Materials and methods

During a 3-year period, we had 254 patients with memory complaints at our university neurology clinic; 106 men, 148 women; mean age 72.5 years (48-95 years). In all patients we performed neurological examination; memory tests including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; 0-30 scale, normal > 24) [9], the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Behavior Section (ADAS-cog; 0-70 scale, normal < 10) [10], the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB; 0-18 scale, normal > 16) [11], and additional Wechsler Memory Scale Revised (WMS-R) [12] if necessary; brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); 99mTc-L,L-ethylcysteinate dimer (ECD) - single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). In addition, we performed MIBG scintigraphy and the method of the test is described previously [13]. Sensitivity and specificity of MIBG scintigraphy is around 90% [13]. The cut-off value of delayed MIBG images of the heart to mediastinum (HM) ratio was 2.0 [6,13]. None had heart failure, diabetic neuropathy, or none were taking serotonergic or any other drugs that might interfere with MIBG scintigraphy [6].

MCI is diagnosed according to the following criteria: Not normal for age, not demented (does not meet criteria (DSM IV, ICD 10) for a dementia syndrome); Presence of cognitive decline - self and/or informant report and impairment on objective cognitive tasks; Essentially preserved basic activities of daily living [1,14]. In addition, amnestic MCI is diagnosed by: Presence of impairment in memory [1,14]. All patients and their families gave informed consent before participating in the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

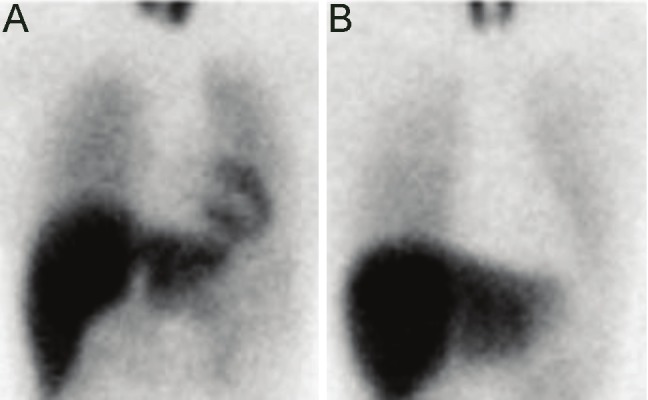

Among the 254 patients, 44 patients were diagnosed with amnestic MCI; and 13 of 44 cases (30%) showed low MIBG uptake (Figure 1). None of 13 patients had the core clinical features of DLB (dementia and spontaneous parkinsonism). None of 13 patients had hippocampal atrophy by brain MRI scans using VSRAD (Voxel-based Specific Regional analysis system for Alzheimer's disease) MRI morphometry software, or other neurological/ imaging abnormalities relevant to the memory disorder.

Figure 1.

Representative cases of 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy. A: normal control (the HM ratio 2.84), B: Case 2 of 13 amnestic mild cognitive impairment cases (the HM ratio 1.41). MIBG: metaiodobenzylguanidine; The HM ratio: the heart to mediastinum ratio; The cut-off value of delayed MIBG images (4 hours after injection of 111 MBq MIBG, depending on uptake-1 [neuronal uptake], reflecting cardiac sympathetic nerve activity) of the HM ratio was 2.0. Reduced HM ratio indicates peripheral noradrenergic depletion.

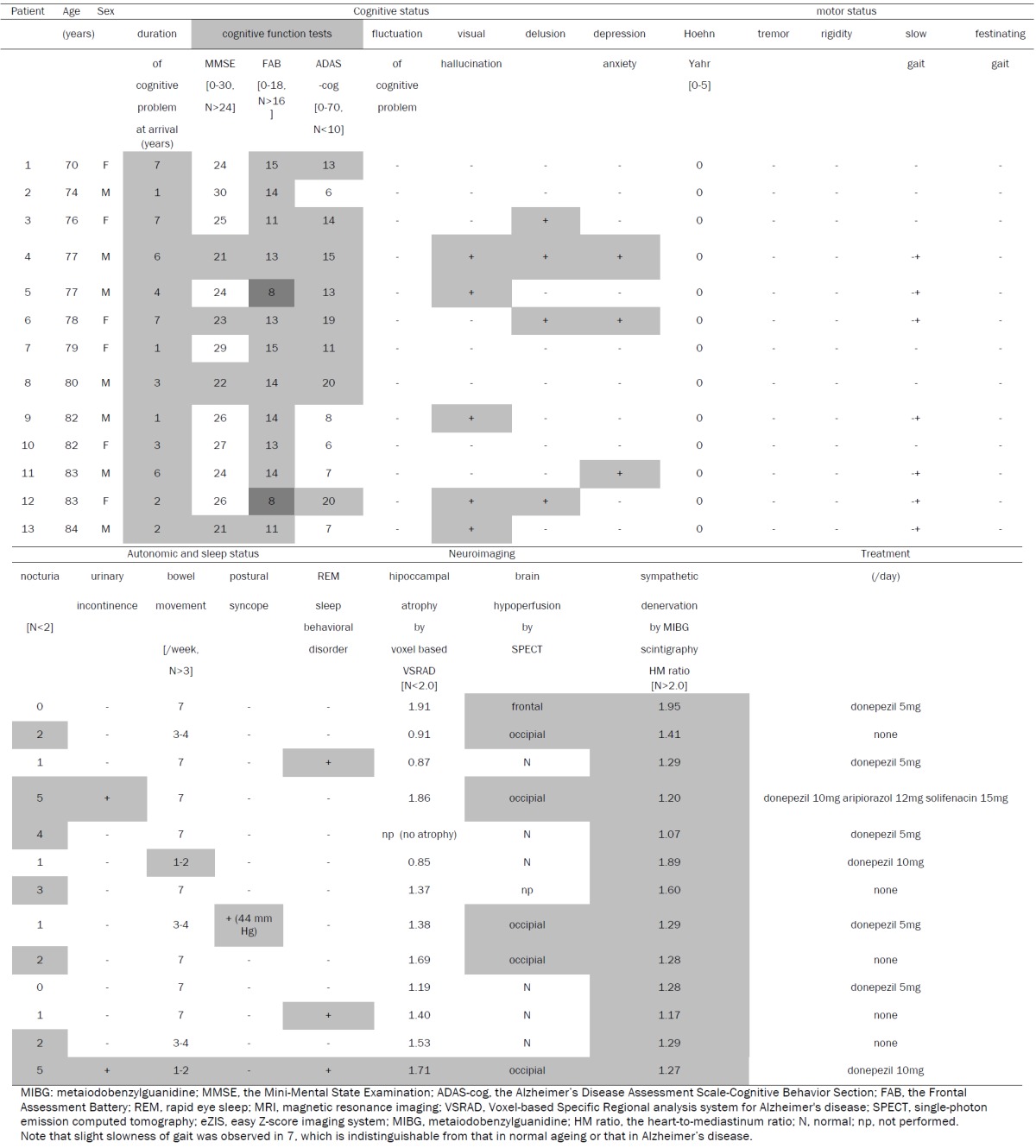

The 13 patients had the following clinical characteristics (Table 1): uniformly elderly (mean age 78.9 years, 70-84 years), with an equal sex ratio (7 male, 6 female), have relatively slow progression (mean duration of memory disorder at arrival, 3.8 years, 1-7 years), preserved general cognitive function (mean MMSE 24.8, 21-30; mean ADAScog 12.2, 6-20). In addition to memory impairment, these patients commonly showed low frontal function by FAB (12.5/18, 8-15) and some had mild visual hallucination (in 5); therefore, they are regarded multidomain amnestic MCI [1,14]. Other than memory disorder, they had autonomic disorder (nocturia in 7, urinary incontinence in 2, constipation in 2, postural hypotension in one), REM [rapid-eye movement] sleep behavioral disorder (in 3), and occipital hypoperfusion by ECD-SPECT (in 5).

Table 1.

Thirteen patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment without the core clinical features of DLB with reduced 123I-MIBG uptake.

|

Discussion

It is important to identify MCI patients with a higher risk of progression to dementia, since early treatment might delay disease progression [1,2]. However, identifying the causes of MCI is not easy, even though management should be individualized depending on the cause. Regarding Lewy body pathology, approximately 8-17% of neurologically normal subjects over 60 years of age have Lewy bodies on postmortem examination, referred to as incidental Lewy body disease [15]. Previously, clinical clues to suggest Lewy body pathology include postural hypotension [16], constipation [17], REM sleep behavioral disorder [18] and depression [19]. Similarly, some pathology-proven Lewy body disease patients have shown amnestic MCI, before progressing to the core clinical features of DLB (dementia and spontaneous parkinsonism) [20-22]. However, it is regarded difficult to ante-mortem diagnose such early-stage DLB patients.

Using MIBG scintigraphy, Fujishiro et al. reported two patients with a clinical diagnosis of amnestic MCI who had low MIBG uptake, without the core clinical features of DLB [8]. One patient, 75-year-old male, had episodes of RBD, visual hallucination, and spontaneous parkinsonism two years after amnestic MCI is diagnosed. The other patient, 62-year-old female, developed amnestic MCI, and had occipital hypo-metabolism on 18F-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography (PET) scan. None of both patients had diabetes and other cardiac diseases that might affect the MIBG uptake.

In the present study, we described 13 amnestic MCI cases without the core clinical features of DLB (dementia and spontaneous parkinsonism) with low MIBG uptake. Since sensitivity and specificity of MIBG scintigraphy is high (around 90%) [13] and none of 13 patients had comorbid diseases or drugs that might affect MIBG uptake [6,7,13], these patients most probably have Lewy body pathology. In addition to memory impairment, these patients commonly showed low frontal function by FAB [23] and some had mild visual hallucination; therefore, they are regarded multidomain amnestic MCI. Other than memory disorder, they had autonomic disorder (nocturia, constipation, postural hypotension in one), REM sleep behavioral disorder, and occipital hypoperfusion by ECD-SPECT [24]. All these features are rare in AD, but are commonly reported in combination with, or an isolated feature of, DLB [16-19,23,24]. This cohort of multidomain amnestic MCI cases may present with early stage DLB because of presence of low MIBG uptake. MIBG scintigraphy may help differentiating early stage DLB from early stage AD before full clinical features appear.

In conclusion, the present cohort of multidomain amnestic MCI cases may present with early stage DLB because of presence of low MIBG uptake. Clinically, they commonly have low FAB, and may have visual hallucination, autonomic and sleep disorders.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have conflict of interest

References

- 1.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer's Association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKeith I, Mintzer J, Aarsland D, Burn D, Chiu H, Cohen-Mansfield J, Dickson D, Dubois B, Duda JE, Feldman H, Gauthier S, Halliday G, Lawlor B, Lippa C, Lopez OL, Carlos Machado J, O'Brien J, Playfer J, Reid W International Psychogeriatric Association Expert Meeting on DLB. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippa CF, Duda JE, Grossman M, Hurtig HI, Aarsland D, Boeve BF, Brooks DJ, Dickson DW, Dubois B, Emre M, Fahn S, Farmer JM, Galasko D, Galvin JE, Goetz CG, Growdon JH, Gwinn-Hardy KA, Hardy J, Heutink P, Iwatsubo T, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Leverenz JB, Masliah E, McKeith IG, Nussbaum RL, Olanow CW, Ravina BM, Singleton AB, Tanner CM, Trojanowski JQ, Wszolek ZK DLB/PDD Working Group. DLB and PDD boundary issues: Diagnosis, treatment, molecular pathology, and biomarkers. Neurology. 2007;68:812–819. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256715.13907.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu XS, Okamura N, Arai H, Higuchi M, Matsui T, Tashiro M, Shinkawa M, Itoh M, Ido T, Sasaki H. 18F-fluorodopa PET study of striatal dopamine uptake in the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;55:1575–1577. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.10.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashina S, Yamazaki J. Neuronal imaging using SPECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:939–950. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, Mori F, Kakita A, Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H. Axonal alpha-synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131:642–650. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujishiro H, Nakamura S, Kitazawa M, Sato K, Iseki E. Early detection of dementia with Lewy bodies in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment using (123)I-MIBG cardiac scintigraphy. J Neurol Sci. 2011 Nov 28;315:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state; a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libb JW, Coleman JM. Correlations between the WAIS and revised Beta, Wechsler memory scale and Quick test in a vocational rehabilitation center. Psychol Rep. 1971;29:863–865. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1971.29.3.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tateno F, Sakakibara R, Kishi M, Ogawa E, Terada H, Ogata T, Haruta H. Sensitivity and specificity of metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial accumulation in the diagnosis of Lewy body diseases in a movement disorder clinic. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:395–397. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Bäckman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Tredici K, Duda JE. Peripheral Lewy body pathology in Parkinson's disease and incidental Lewy body disease: four cases. J Neurol Sci. 2011;310:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida M, Fukumoto Y, Kuroda Y, Ohkoshi N. Sympathetic denervation of myocardium demonstrated by 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in pure-progressive autonomic failure. Eur Neurol. 1997;38:291–296. doi: 10.1159/000113396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tateno F, Sakakibara R, Kishi M, Ogawa E, Takada N, Hosoe N Suzuki Y, Takahashi M, Uchiyama T, Yamamoto T. Constipation and metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy abnormality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujishiro H, Iseki E, Murayama N, Yamamoto R, Higashi S, Kasanuki K, Suzuki M, Arai H, Sato K. Diffuse occipital hypometabolism on 18 FFDG PET scans in patients with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies? Psychogeriatrics. 2010;10:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi K, Sumiya H, Nakano H, Akiyama N, Urata K, Koshino Y. Detection of Lewy body disease in patients with late-onset depression, anxiety and psychoticdisorder with myocardial meta-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:55–65. doi: 10.1002/gps.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jicha GA, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Johnson K, Cha R, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathologic outcome of mild cognitive impairment following progression to clinical dementia. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:674–681. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander I, Tröster A. Neuropsychological characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia: differentiation, early detection, and implications for “mild cognitive impairment” and biomarkers. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18:103–119. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markesbery WR. Neuropathologic alterations in mild cognitive impairment: a review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:221–228. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanyu H, Sato T, Kume K, Takada Y, Onuma T, Iwamoto T. Differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer disease using the frontal assessment battery test. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1034–1035. doi: 10.1002/gps.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tateno M, Kobayashi S, Saito T. Imaging improves diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:233–240. doi: 10.4306/pi.2009.6.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]