Summary

Background

Until now there has been no study that directly compares the effect of lansoprazole and pantoprazole administered intravenously on intragastric acidity. The aim of this study is to compare the effect of lansoprazole (30 mg) and pantoprazole (40 mg) administered intravenously on gastric acidity.

Material/Methods

Helicobacter pylori-negative healthy volunteers were recruited in this open-label, randomized, two-way crossover, single centre study. Lansoprazole at 30 mg or pantoprazole at 40 mg was intravenously administered twice daily for 5 consecutive days with at least a 14-day washout interval. Twenty-four-hour intragastric pH was continuously monitored on days 1 and 5 of each dosing period.

Results

Twenty-five volunteers completed the 2 dosing periods. The mean intragastric pH values were higher in subjects treated with lansoprazole than those with pantoprazole on both day 1 (6.41±0.14 vs. 5.49±0.13, P=0.0003) and day 5 (7.09±0.07 vs. 6.64±0.07, P=0.0002). Significantly higher percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 and pH >6 were found in the subjects treated with lansoprazole than those with pantoprazole on day 1 (pH >4, 87.12±4.55% vs. 62.28±4.15%, P=0.0012; pH >6, 62.12±4.12% vs. 47.25±3.76%, P=0.0216) and pH >6 on day 5 (76.79±3.77% vs. 58.20±3.77%, P=0.0025).

Conclusions

Intravenous lansoprazole produces a longer and more potent inhibitory effect on intragastric acidity than does intravenous pantoprazole.

Keywords: lansoprazole, pantoprazole, intravenous administration, intragastric acidity, volunteers

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been used widely and achieved great benefits in managing acid-related upper gastrointestinal diseases, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated gastric mucosal damage, hypersecretory states such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and even functional dyspepsia. The pathophysiologic basis of these management benefits lies in their potent gastric acid inhibitory effects.

Intravenous administration of a PPI, which usually provides gastric acid suppression faster than oral administration [1], is mostly recommended for patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with acid-related diseases, who cannot tolerate oral intake, or those with a disorder of swallowing [2]. There have been many studies that compared the effects of different PPIs through oral administration, but only 1 study evaluated the effect of different PPIs on the intragastric acidity in healthy adults through intravenous administration (esomeprazole [40 mg] vs. lansoprazole [30 mg]) [3]. However, there has been no study that directly compares the efficacy of intravenous lansoprazole and pantoprazole in terms of inhibiting intragastric acidity. The aim of this study was to evaluate the inhibitory effect of intravenous lansoprazole (30 mg) and pantoprazole (40 mg) twice-daily for 5 consecutive days on intragastric acidity in healthy Chinese volunteers.

Material and Methods

Subjects

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Healthy male or non-pregnant female volunteers aged 18–45 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 19–25 kg/m2 and with extensive metabolizer (EM) status for CYP2C19 genotypes, were included. Subjects who had a history of a severe disease in any major organ (eg, renal, hepatic or cardiovascular disease) that might affect the pharmacokinetics of PPIs were excluded. Subjects who had current or past (within 6 months prior to the screening) endoscopic evidence of esophageal pathology or a history of gastric or esophageal surgery, who took PPIs, and NSAIDs or any other drugs that may cause injuries to the gastric mucosa within 2 weeks before the first dose of the study drug, and who would require any concomitant drugs during the study, were excluded. Subjects who had a history of significant clinical illness, drug or alcohol abuse, and any conditions that could modify the absorption of the study drugs as judged by the investigators within the 2 weeks before the first dose of study drugs were also excluded.

The study was performed according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to being enrolled in the trial.

Study design

The study was an open label, randomized, 2-way crossover design, and performed at 1 center. An initial screening visit took place within 14 days prior to the first study day and consisted of a complete medical history, physical examination and measurement of laboratory safety variables such as renal and hepatic functions, as well as the urine pregnancy test for female subjects. In addition, CYP2C19 genotypes and the status of H. pylori infection were determined as described below.

Eligible subjects were randomized to receive either lansoprazole (Jiangsu Aosaikang Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Nanjing, China) at 30 mg or pantoprazole (Nycomed GmbH, Konstanz, Germany) at 40 mg via intravenous infusion within 30 min twice daily at 8:00 am and 8:00 pm on day 1 through day 5. Then, after a washout interval of 14–21 days, the subjects were switched to receive another PPI (pantoprazole or lansoprazole, where appropriate), in the same fashion as described above.

The subjects took visits 2–12 days before the first dosing period and 5–7 days after each dosing period. Standardized meals, not high in fat or calories, were provided by the research center from day 1 through day 5. Meals were administered in an identical fashion during both dosing periods. Alcohol and caffeinated beverages, and any new or intensified physical activities were not permitted during the study period until the completion of the last follow-up visit. On days 1 and 5 of each of the dosing periods, 24-h intragastric pH was monitored as described below.

Measurement of intragastric pH

After a 12-h fast, 24-h intragastric pH was recorded starting from 8 am after the first dose on day 1 and day 5 of each dosing period using a pH-sensitive microelectrode (Medtronic, Copenhagen, Denmark) linked to a Digitrapper MKIII recording system (Medtronic). The electrode was inserted trans-nasally and placed about 8–10 cm below the lower esophageal sphincter as identified by a sharp decrease in pH indicating the point at which the electrode crossed the sphincter. There were marks on the surface of the catheter to identify the position. Using a microprocessor, this unit was able to record the subject’s intragastric pH over the 24-h period. Then, the Digitrapper™ data were downloaded onto a personal computer to calculate the percentage of time in which the intragastric pH was >4 and percentage of time in which the intragastric pH >6, along with the 24-h median intragastric pH. A 2-point calibration of the probe was made before each recording, using standard buffers of a pH of 7.01 and pH of 1.07.

All the subjects stayed in the research center from 8:00 pm on the day prior to pH monitoring. At 6:00–7:00 am of the pH monitoring day, the pH electrode was placed 30 min before the first dosage and the measurement of the intragastric pH values started at the same time of the first dosage, and continued until 8 am on the next day. The pH monitoring interval continued at least 22 hours. The subjects were mobile and were instructed not to lie down for longer than 10 min each time during the day and lie down to sleep at 10 pm at night until 6 am next morning. Subjects were prohibited from eating or drinking after 8 pm of the monitoring day.

Assessment of CYP2C19 genotypes and H. pylori infection

Metabolizer status for CYP2C19 genotypes was assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique as previously described [4]. Briefly, 0.2 ml blood was used for DNA extraction by QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kits (QIAGEN Company); 100 ng DNA was amplified in the first round of PCR in a 25 μl reaction volume containing 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1×PCR buffer (Takara, Dalian, China), 0.5 U Hot-start Taq (Takara), 200 μmol/L dNTP, 1 μmol/L primers: 5′ CCATTATTTAACCAGCTAGG 3′ and 5′CCATTATTTAACCAGCTAGG 3′ at the following condition: denaturation at 95°C for 5 min and followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min and then extension at 72°C for 7 min. 1 μl product of the first round of PCR was then subjected to the second round of PCR with 1 μmol/L primers for the exon 4 of CYP2C19 (5′ TCTGTTAACAAATATGAAGTGTT3′ and 5′ TCTAGGCAAGACTGTAGTATTC3′) and primers for the exon 5 of CYP2C19 (5′ TTGGCATATTGTATCTATACCTT3′ and 5′ CTAGTCAATGAATCACAAATAC3′). The second round of PCR was performed under the following conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 5 min and followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min and then extension at 72°C for 7 min. The products were then separated by 1% gel electrophoresis and subjected to DNA sequencing analysis (Invitrogen Corporation).

H. pylori infection status was detected by a 13C-labeled urea breath test within 7 days before the enrollment. This test has been reported to have high sensitivity, specificity and accuracy [5,6].

Safety analysis

Physical examinations, abdominal ultrasonography and electronic cardiograms were conducted and blood samples collected 2 days before and 5–7 days after each dosing period. All reported or observed adverse events such as symptoms, signs, abnormal laboratory testing, abdominal ultrasonography or electronic cardiograms were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). ‘Per protocol’ population was used in the efficacy analysis, which included all subjects who satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria and complied with study drug administration per protocol, and had no major protocol deviations that might affect intragastric pH. The primary efficacy outcome was analyzed by comparing the percentage of time that the intragastric pH was higher than a threshold of 4 and 6 between treatment groups on days 1 and 5. The percentage of time in which the pH >4 and pH >6 over the 24-h period and median 24-h intragastric pH were analyzed using a mixed model ANOVA with fixed effects for period, sequence and treatment and a random effect for subjects within sequence. The mean value for each treatment and mean treatment differences (lansoprazole vs. pantoprazole) were estimated with least-squares mean (LSM) percentages ± standard error of means (SEM). The data on day 1 and 5 were analyzed. The percentage of subjects with intragastric pH above 4 for more than 12 h and pH above 6 for more than 16 h on day 1 and day 5 was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. The safety data from all subjects who received at least 1 dose of study medication were summarized descriptively, and analyzed by the chi-square test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subjects

Twenty-three (13 males and 10 females, ages ranging between 21 and 43 years) H. pylori-negative healthy volunteers were enrolled in the study. All completed the 2 dosing periods.

The subjects were divided into 2 groups; 12 and 11 received intravenous lansoprazole and pantoprazole at the first dosing period, and then intravenous pantoprazole and lansoprazole during the second dosing period, respectively. There were no differences in the sex distribution (8/4 vs. 5/6 males/females), age (28.92±6.97 vs. 24.45±2.54 years), or BMI (21.95±1.39 vs. 21.73±1.51 kg/m2) between the 2 groups.

Intragastric pH

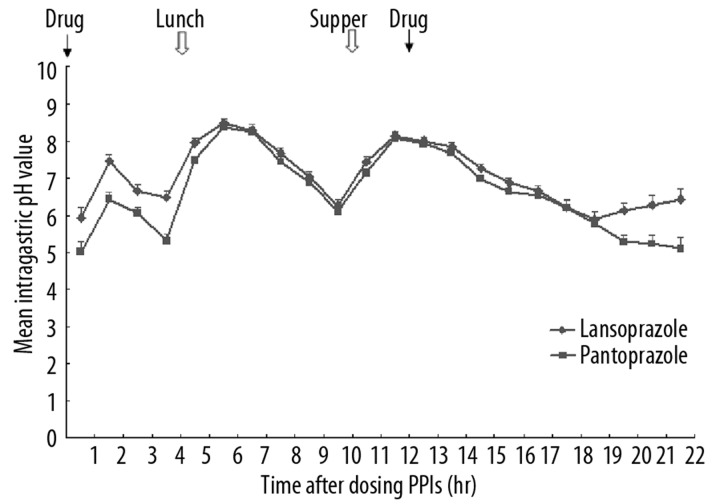

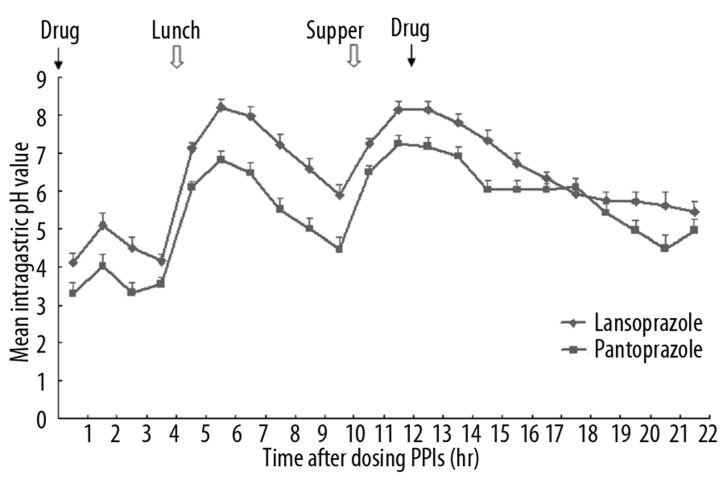

The mean intragastric pH values in each hour on day 1 and day 5 are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Generally, on both day 1 and day 5, after the first dosing at 8 am, the pH value increased, with a transient drop starting at 1.5 h, and then increased again at 3.5 h. At 6.5 h after the dosing, the pH value dropped and continued to drop until at 9.5 h, when the pH value rebounded. After the second dosing at 8 pm (12 h after the first dosing), the pH values dropped slightly, but maintained at levels higher than those at the beginning of the dosing.

Figure 1.

The mean intragastric pH values on day 1 after two doses of intravenous lansoprazole or pantoprazole at hours 0 and 12, respectively.

Figure 2.

The mean intragastric pH values on day 5 after two doses of intravenous lansoprazole or pantoprazole at hours 0 and 12, respectively.

There were significant differences in the pH values at the time points, between hours 2–14 on day 1, and the time points in hours 1–5, 21 and 22 on day 5.

The percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 and pH >6 over the first 4 h and 24 h on day 1 and 5 are presented in Table 1. Significantly higher percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 and pH >6 were observed in the subjects treated with lansoprazole than in those treated with pantoprazole during the first 4 hours, on day 1 and pH >6 on day 5.

Table 1.

Effect of 5 days’ dosing with intravenous lansoprazole or pantoprazole on intragastric acidity in 25 healthy subjects.

| Time point | % of time with intragastric pH>4 (LSM±SEM) | P value | % of time with intragastric pH>6 (LSM±SEM) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lansoprazole | Pantoprazole | Lansoprazole | Pantoprazole | |||

| Day 1 | ||||||

| 0–4 h | 43.34±5.95 | 29.34±5.32 | 0.0022 | 23.40±6.15 | 13.22±5.50 | 0.0154 |

| 0–24 h | 85.44±3.33 | 71.65±2.98 | 0.0071 | 63.03±3.89 | 49.46±3.48 | 0.0193 |

| Day 5 | ||||||

| 92.72±0.71 | 87.80±0.71 | 0.8877 | 77.58±1.60 | 67.13±1.60 | 0.0002 | |

LSM – least-squares mean.

The mean time for pH >4 and pH >6 with lansoprazole was shorter than with pantoprazole on day 1, but the difference was not statistically significant (109.61±32.15 min vs. 153.42±29.36 min, P=0.3304 for pH 4; and 211.93±39.18 min vs. 288.43±35.79 min, P=0.1706 for pH 6).

The percentages of subjects with intragastric pH>4 for at least 12 hours were 94% and 83% for lansoprazole and pantoprazole, respectively, on day 1, and 100% for both lansoprazole and pantoprazole on day 5. The percentages of subjects with intragastric pH>6 for at least 16 hours were 31% and 13% on day 1, and 67% and 43% on day 5 for lansoprazole and pantoprazole, respectively.

Safety and tolerability

Both lansoprazole and pantoprazole, intravenously administrated, were well tolerated. A drug-related moderate skin rash occurred in a female volunteer after a dose of pantoprazole, and mild somnolence which might be related to lansoprazole occurred after a dose of lansoprazole. These adverse events did not result in drug discontinuation, and disappeared without any medication. No serious adverse events occurred. There were no clinically significant abnormal laboratory, ultrasonographic and electrocardiographic findings.

Discussion

Maintenance of the intragastric pH above 4 is crucial for preventing stress-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding [7–9]. Moreover, the recent guidelines and consensus have recommended elevating the intragastric pH above 6 with intravenous high-dose PPIs in the treatment of non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding [2,10–14]. This recommendation is based on the evidence that the acidic environment does not benefit to the coagulation, and neutralizing the intragastric acidity is required for successful coagulation. Laterre et al. [15] reported that a large intravenous bolus dose (80 mg) of omeprazole, followed by 8 mg per h, achieved more than 80% of the dosing period with pH above 6. In addition, van Rensburg et al. [16] reported that in patients with acute bleeding peptic ulcers, an intravenous bolus injection of 80 mg of pantoprazole after successful endoscopic hemostasis, followed by continuous infusion of either 6 mg/h or 8 mg/h pantoprazole for 72 h, rapidly increased the intragastric pH to values of above 6.

A number of trials have compared the effects of different PPIs on gastric acidity in healthy volunteers, patients on aspirin or NSAIDs and those with pathological conditions. It has been shown that the relative potencies of the 5 available PPIs compared to omeprazole were 0.23, 0.90, 1.00, 1.60, and 1.82 for pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole, respectively, in the population with GERD [17]. Compared with healthy volunteers, patients with GERD needed a 1.9-fold higher dose and H. pylori-positive individuals needed only about 20% of the dose to achieve a given increase in mean 24-h intragastric pH. However, these data are based on clinical trials using oral administration, which may not reflect the situation where the PPIs are administrated intravenously. There have been clinical trials evaluating the effect of PPIs on intragastric acidity; however, there have been no studies comparing, head-to-head, the effect of intravenous pantoprazole and lansoprazole in the same clinical study. In the present study, we conducted an open-label, randomized, 2-way crossover, single centre clinical trial, which was the first to date to compare the effect of lansoprazole (30 mg) and pantoprazole (40 mg) administered intravenously twice daily for 5 consecutive days on gastric acidity.

Pantoprazole is one of the most widely used PPIs in the world. Several previous studies evaluating whether oral or intravenous pantoprazole is a consistent and long-lasting inhibitor of gastric acid secretion have achieved satisfactory results in patients with acid-related diseases [18,19]. Numerous studies and meta-analyses have confirmed the efficacy of intravenous pantoprazole in treating peptic ulcer bleeding and stress ulcer bleeding, and thus pantoprazole is now one of the PPIs most used intravenously in treating non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Lansoprazole is also a newly developed PPI with high effectiveness in controlling intragastric acid and in treating acid-related upper gastrointestinal diseases [20–26]. Several clinical trials have been conducted to compare the effect on intragastric acid control by oral lansoprazole with that by either oral or intravenous pantoprazole in healthy volunteers and patients with GERD [27–30]. Almost all the results showed that oral lansoprazole is stronger or equal to oral or intravenous pantoprazole in controlling intragastric acid. Huang et al. [30] reported a crossover trial of 74 healthy male volunteers who received oral lansoprazole 30 mg or pantoprazole 40 mg once daily for 5 consecutive days with at least a 2-week washout period between the regimens. It was found that compared with pantoprazole, lansoprazole produced higher mean 24-h intragastric pH values, greater proportions of time in which the intragastric pH was above 3, 4 and 5 on day 1, a higher mean 24-h intragastric pH value, and a greater percentage of time that the intragastric pH was above 4 on day 5. Freston et al. [28] reported an open label, 2-way crossover, and single-center study comparing the effect of lansoprazole at 30 mg per nasogastric tube with that of pantoprazole at 40 mg intravenously for 5 consecutive days. Similarly, it was found that lansoprazole produced higher mean 24-h intragastric pH values relative to pantoprazole on day 1 and day 5. Lansoprazole sustained the intragastric pH above 3 (days 1 and 5), 4, and 5 (day 1) longer than pantoprazole.

Although previous trials [31,32] have demonstrated that the effects on intragastric acidity with lansoprazole by oral and intravenous routes are similar, and compared with pantoprazole in healthy volunteers or patients with pathological conditions, oral lansoprazole produced a more potent ability in inhibiting gastric acid secretion. Intravenous formulation is still the first choice for acute non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding. In addition, some patients requiring acid suppression may be unable to take oral medications due to dysphagia. Therefore, in many cases intravenous lansoprazole cannot be replaced by its oral formulation. However, there has been no study that directly compares the effect on intragastric acidity between intravenous lansoprazole and intravenous pantoprazole. The present study was the first to explore this issue. In the present study, our findings are in agreement with the results of previous trials and found that lansoprazole produced significantly higher mean intragastric pH values and percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 and pH >6 than pantoprazole on day 1 and pH >6 day 5.

The importance of the CYP2C19 genotype in acid suppression by PPIs has been elucidated [33]. EMs and poor metabolizers (PMs) of this isoenzyme differ in their elimination of drugs (such as PPIs) that depend on it for clearance. Therefore, the genetic difference in drug metabolism can cause a wide interindividual variation in antacid effect of PPIs (ie, PMs are associated with a stronger effect than Ems). For example, the researchers noted that therapeutic efficacy of PPIs is strongly linked to interpatient differences in drug metabolism [33]. In the present study, we only analyzed the inhibitory effect of PPIs on gastric acid secretion in volunteers with EMs. Thus, the results of the present study may be relevant in the populations with a low prevalence of PMs, such as in the Chinese, where the reported prevalence of PMs is about 12.7% [34], but may not be applicable to other populations where the prevalence of PMs is high, which is a major limitation of this study. In addition, in clinical practice the patients likely to receive intravenous PPI treatment are those in a critical care setting and fasting conditions. The present study was conducted with healthy volunteers who did not accurately reflect the demographic characteristics and comorbidities present in critically ill patients in intensive care units. The efficacy of intravenous lansoprazole in clinical settings needs further study.

Conclusions

Both pantoprazole and lansoprazole administered intravenously produced strong inhibition of gastric acid control, while lansoprazole administered intravenously significantly improved the percentage of time with intragastric pH >4, the median 24-hour intragastric pH on day 1 and day 5 relative to pantoprazole. The results of the present study indicate that lansoprazole administered intravenously is more effective in maintaining high intragastric pH in healthy subjects than is pantoprazole, and offers the potential to treat acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance of Jian-Ping Lu and Ai-Fang Xu in facilitating the conduction of this study. We are also grateful for the assistance of Medjaden Bioscience Limited in language polishing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Bardou M, Martin J, Barkun A. Intravenous proton pump inhibitors: an evidence-based review of their use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs. 2009;69:435–48. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 152:101–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisegna JR, Sostek MB, Monyak JT, Miner PB., Jr Intravenous esomeprazole 40 mg vs. intravenous lansoprazole 30 mg for controlling intragastric acidity in healthy adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:483–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li ZS, Zhan XB, Xu GM, et al. Effect of esomeprazole and rabeprazole on intragastric pH in healthy Chinese: an open, randomized crossover trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:815–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suto G, Vincze A, Pakodi F, et al. 13C-Urea breath test is superior in sensitivity to detect Helicobacter pylori infection than either antral histology or rapid urease test. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94:153–56. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokoro C, Inamori M, Koide T, et al. Influence of pretreatment with H2 receptor antagonists on the cure rates of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(5):CR235–40. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantin VD, Paun S, Ciofoaia VV, et al. Multimodal management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by stress gastropathy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:279–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metz DC. Preventing the gastrointestinal consequences of stress-related mucosal disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:11–18. doi: 10.1185/030079905x16777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spirt MJ. Stress-related mucosal disease: risk factors and prophylactic therapy. Clin Ther. 2004;26:197–213. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrido A, Giraldez A, Trigo C, et al. [Intravenous proton-pump inhibitor for acute peptic ulcer bleeding--is profound acid suppression beneficial to reduce the risk of rebleeding?]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:466–69. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gralnek IM, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:928–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui AJ, Sung JJY. Emerging Strategies in Pharmacologic Management for Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;7:160–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khuroo MS, Farahat KL, Kagevi IE. Treatment with proton pump inhibitors in acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for peptic ulcer bleeding: Cochrane collaboration meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:286–96. doi: 10.4065/82.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laterre PF, Horsmans Y. Intravenous omeprazole in critically ill patients: a randomized, crossover study comparing 40 with 80 mg plus 8 mg/hour on intragastric pH. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1931–35. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rensburg CJ, Hartmann M, Thorpe A, et al. Intragastric pH during continuous infusion with pantoprazole in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2635–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchheiner J, Glatt S, Fuhr U, et al. Relative potency of proton-pump inhibitors-comparison of effects on intragastric pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:19–31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheer SM, Prakash A, Faulds D, Lamb HM. Pantoprazole: an update of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs. 2003;63:101–33. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira Dias L. Pantoprazole: a proton pump inhibitor. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29(Suppl 2):3–12. doi: 10.2165/1153121-S0-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell N, Karol MD, Sachs G, et al. Duration of effect of lansoprazole on gastric pH and acid secretion in normal male volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:105–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoie O, Stallemo A, Matre J, Stokkeland M. Effect of oral lansoprazole on intragastric pH after endoscopic treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:284–88. doi: 10.1080/00365520802538203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howden CW, Metz DC, Hunt B, et al. Dose-response evaluation of the antisecretory effect of continuous infusion intravenous lansoprazole regimens over 48 h. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:975–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iida H, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Early effects of intravenous administrations of lansoprazole and famotidine on intragastric pH. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:551–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin HJ. Effect of oral lansoprazole on intragastric pH after endoscopic treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:765–66. doi: 10.1080/00365520902718721. author reply 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metz DC, Amer F, Hunt B, et al. Lansoprazole regimens that sustain intragastric pH > 6.0: an evaluation of intermittent oral and continuous intravenous infusion dosages. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:985–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong WM, Lai KC, Hui WM, et al. Double-blind, randomized controlled study to assess the effects of lansoprazole 30 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg on 24-h oesophageal and intragastric pH in Chinese subjects with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:455–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2004.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Florent C, Forestier S. Twenty-four-hour monitoring of intragastric acidity: comparison between lansoprazole 30 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:195–200. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199702000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freston J, Chiu YL, Pan WJ, et al. Effects on 24-hour intragastric pH: a comparison of lansoprazole administered nasogastrically in apple juice and pantoprazole administered intravenously. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2058–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taubel JJ, Sharma VK, Chiu YL, et al. A comparison of simplified lansoprazole suspension administered nasogastrically and pantoprazole administered intravenously: effects on 24-h intragastric pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1807–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang JQ, Goldwater DR, Thomson AB, et al. Acid suppression in healthy subjects following lansoprazole or pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:425–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovacs TO, Lee CQ, Chiu YL, et al. Intravenous and oral lansoprazole are equivalent in suppressing stimulated acid output in patient volunteers with erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:883–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen KM, Devlin JW. Comparison of the enteral and intravenous lansoprazole pharmacodynamic responses in critically ill patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klotz U. Clinical impact of CYP2C19 polymorphism on the action of proton pump inhibitors: a review of a special problem. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;44:297–302. doi: 10.5414/cpp44297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tseng PH, Lee YC, Chiu HM, et al. A comparative study of proton-pump inhibitor tests for Chinese reflux patients in relation to the CYP2C19 genotypes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:920–25. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181960628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]