Summary

Background

The aim of this study was to assess head and neck squamous cell cancer and surrounding tissue in computed tomography contrast enhanced and perfusion studies, and to examine the role of perfusion imaging in depiction of tissue infiltration.

Material/Methods

We prospectively evaluated 43 primary malignant head and neck tumors, using standard CT followed by perfusion. Blood flow, blood volume, mean transit time, and permeability values were obtained using regions of interest (ROIs) over lesions and surrounding tissue. Results were compared with histological analysis of resected tissue. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive and negative predictive values were calculated for both methods.

Results

We found significant differences between infiltrated and non-infiltrated tissue, especially with regard to muscles. In case of bone and salivary gland infiltration, change in perfusion parameters did not allow proper diagnosis.

Conclusions

CTP shows promise in depicting malignant infiltration. The combined use of CECT plus CTP results in correct staging of the majority of head and neck tumors.

Keywords: CT perfusion, squamous cell cancer, functional imaging

Background

Head and neck malignancies are relatively common, comprising 3–5% of all neoplasms diagnosed in most Western countries [1,2]. Most malignant pathologies of this anatomical region are squamous cell carcinomas, although a wide variety of other tumor types are found, like adenocarcinomas, lymphomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, and others.

Therapeutic decisions are strongly influenced by tumor stage, as well as by tumor type. In general, early-stage tumors are treated either surgically or with radiotherapy, depending on the expected functional results and the experience of the particular medical center. Patients presenting with advanced stage primary lesion and with metastases to the cervical lymph nodes are usually treated with a combination of 2 methods – surgery and radiotherapy [3,4].

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are routinely used for diagnosing and staging of head and neck malignancies. However, evaluation of single anatomic images has some drawbacks, as early lesion detection remains difficult, and benign processes can mimic malignancies [5]. In many cases inflammatory response and edema cannot be differentiated from the tumor itself, which leads to over-interpretation and upstaging of the disease [5,6]. On the other hand, a pattern of infiltration not accompanied by visible anatomic distortion may result with lesion downstaging.

For better evaluation of tumor extent, dynamic scanning with perfusion imaging (CTP) has been introduced [5–9]. This technique, starting from brain ischemia and brain tumor evaluation, quickly became an effective, simple and reliable method for the assessment of neo-angiogenesis, which is typical for tumors [5,7,8,10]. According to the contemporary literature, CTP during recent years has been widely used to detect, stage and predict the behavior of cancer and to assess the response to radio- and chemotherapy [7,8,10–17]. However, it has some important drawbacks which should be taken into consideration, especially when evaluating questionable lesions – it is easily influenced by motion artefacts and partial volume effect, some structures are much better estimated than others, and symmetry of blood vessels must be observed.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the cases of head and neck malignant pathologies, examined with CT followed by CTP, and to compare the results of CTP with histopathologic results, with special regard to sensitivity, specificity, and false-negative and false-positive results.

Material and Methods

Patients

The institutional review board approved this study, with written informed consent obtained from all enrolled subjects. A total of 43 patients were prospectively recruited into this study (39 men, 4 women; average age, 54.5 y; age range 31–72 y). Inclusion criteria comprised a clinical diagnosis of cancer in the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx, confirmed on biopsy and qualified for surgical treatment. In 4 cases a salivary gland tumor was diagnosed; these patients were excluded since these neoplasms have different behavior. In 39 cases, SCC was proven on biopsy. Finally, 39 patients underwent detailed analysis with perfusion. In all cases no prior treatment to the head or neck region had been attempted. The detailed characteristics of patients, together with initial (clinical) TNM staging, are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all patients, including primary site of cancer and cancer type.

| Number of patients | Primary site of cancer | Cancer type based on biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Oral cavity | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 1 | Oral cavity | Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| 1 | Oral cavity | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| 11 | Oropharynx | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 2 | Parapharyngeal space | Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| 12 | Hypopharynx | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 10 | Larynx | Squamous cell carcinoma |

Table 2.

Basic information concerning clinical staging, with the use of TNM classification.

| Site of origin | Number of patients with initial staging based on clinical evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1N0 | T2N0 | T2N1 | T2N2b | T3N1 | T3N2a | T3N2b | T4N2b | |

| Tongue | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Floor of the mouth | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Retromolar trigone | 1 | |||||||

| Palatine tonsil | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tongue base | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Pyriform sinus | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Vocal cord | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Supraglottis | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Postcricoid area | 1 | |||||||

Imaging studies

All patients were examined using a 64-section MDCT (VCT, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). First, routine head and neck examination was performed from the level of skull base to thoracic inlet, using 1.25 mm contiguous sections (120 kV, 170 mA and 0.5 s rotation time), before and after contrast medium administration (80 ml + 20 ml of saline flush, injection rate – 1 ml/s, with 100 s delay), using soft tissue and bone reconstruction kernels.

Afterwords, CTP acquisition was performed according to standard protocol. Based on the coverage along the z -axis of the tumor, an 8 cm region of scanning encompassing the entire visible lesion was selected for the cine imaging. For the cine imaging, an intravenous injection of 50 ml of Iopromidum (Visipaque 320, GE Healthcare) was administered, at a rate of 4.5 ml/s. Multiple sequential acquisitions commenced 5 s after the start of the intravenous injection to allow the spiral acquisition of baseline unenhanced images, and was continued for a total duration of 50 s. The following parameters were used:

120 kV, 100 mAs, 0.4 s gantry rotation time, 5 mm reconstructed section thickness, 110 mm/s table speed, 250 mm of field of view and 512×512 matrix. During the examination, patients were asked to breathe quietly. In order to minimize the radiation dose in the CT perfusion protocol and decrease the noise, half the mAs used for a conventional diagnostic image (200 mAs) were used (100 mAs).

Data analysis

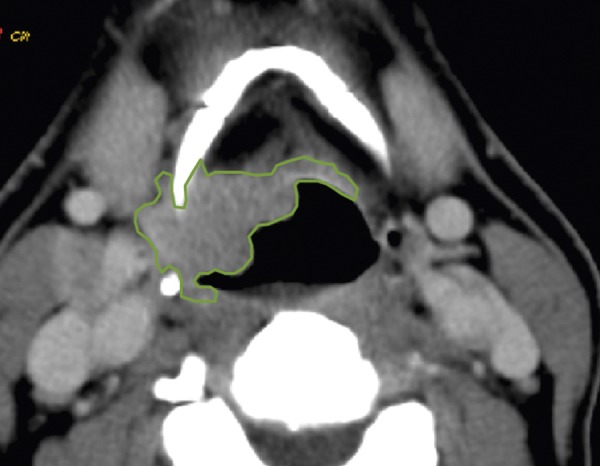

Data was transferred to an image processing workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.2, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI)) and analyzed using perfusion software (CT Perfusion, version 3). The analytical method used in this software was based on the deconvolution method. The arterial and venous inputs were determined by placing region of interest (ROI) over either the common carotid artery or the internal carotid artery and jugular vein. The ROI was drawn over the tumor on 1 selected axial scan, manually, to cover the whole area of pathologic contrast enhancement, representing malignant tissue, according to evaluating radiologists, based on CECT images (Figure 1). When outlining the tumor, attempts were made not to include obvious areas of necrosis; however, areas of heterogeneity and small hypodense foci (<5 mm) were included. In case of structures in the vicinity of the tumor, which could be suspected for malignant infiltration (blurred margins, asymmetric appearance, slight contrast enhancement) but not obviously infiltrated, additional ROI’s were placed on them and on the same structures contralaterally, using symmetry axis with manual correction. These structures included muscles, salivary glands, tonsils, fat, bone, and cartilages. ROI placement on contralateral structures was done in order to compare perfusion parameters between structures in the vicinity of the tumor, suspected for infiltration, and those obviously not affected.

Figure 1.

An example of tumor outlining based on CTP scan. ROI is hand-drawn, with attempt to include the whole area of pathologic tissue visible on this axial scan.

In case of a tumor, measurements were taken from 1 section containing the greatest and most viable part of the tumor (least necrotic). In case of other structures, measurements were taken from sections containing the greatest area of suspected pathology or the largest volume of evaluated structure.

Individual perfusion maps were generated for blood flow (BF, ml/100 g/min), blood volume (BV, ml/100 g), mean transit time (MTT, s) and permeability surface (PS, ml/100 g/min). The mean values of the 4 perfusion parameters obtained for each individual patient were then noted by 2 radiologists by consensus, separately for each tumor and all evaluated surrounding structures suspected for infiltration. Results were then compared with histopathologic reports.

Staging, based on the result of imaging studies (CECT + CTP) is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Head and neck cancer staging in a group of 39 patients, based on the results of diagnostic imaging studies.

| Site of origin | Number of patients with staging based on CT evaluation (CECT + CTP) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1N0 | T2N0 | T2N1 | T2N2b | T3N1 | T3N2a | T3N2b | T4N2b | |

| Tongue | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Floor of the mouth | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Retromolar trigone | 1 | |||||||

| Palatine tonsil | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tongue base | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Pyriform sinus | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Vocal cord | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Supraglottis | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Postcricoid area | 1 | |||||||

Surgery and histopathology

Tumors were excised based on the consensus between clinical and imaging findings.

Several approaches and techniques were used: intra-oral approach, in some cases with mandibulotomy, or segmental mandibular resection, pharyngectomy, pharyngo-laryngectomy with “en bloc” resection and laryngectomy. In case of deep “en bloc” resection, histopathological evaluation of all important head and neck structures was performed – they were excised separately for pathologic analysis and labeled; however, such resection took place in 16 cases. For other patients, histological evaluation of a limited number of structures was available since not all of them were excised. In these patients, the decision concerning the character of a given structure or space (malignant or healthy) was made based on radiologic evaluation and the surgeon’s impression at the time of surgery. For instance, structures having normal appearance on CECT, placed clearly on a different level than primary tumor (e.g., thyroid cartilage in case of T2 tongue cancer) were considered to be not affected, and included into statistical analysis as not infiltrated. For these structures having normal CT appearance, no clinical signs of infiltration and being clearly separated from the tumor (other level, other space), the reference (gold standard) was radiologic-clinical assessment.

The resected tumor underwent standard histopathological analysis. An attempt was made to remove every tumor with at least a 5-mm margin of healthy tissue. This margin was impossible to achieve in 9 cases where the infiltration encased pterygoid muscles, carotid space and prevertebral space. Cases of carotid and prevertebral space infiltration were confirmed based on intra-operative evaluation.

Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of standard contrast-enhanced CT and CTP were calculated based on each subsite, and additionally for each structure separately. In case of subsites, evaluation differences in cumulative sensitivity and specificity between the imaging modalities were tested for statistical significance using the McNemar test.

Results

Study group

Of the 39 patients, 2 had T2N0, 9 had T2N1, 6 had T2N2b, 4 had T3N1, 4 had T3N2a, 8 had T3N2b, and 6 had T4N2b, according to radiologic evaluation (CECT + CTP). Lymph nodes evaluation and N staging were made solely based on CECT images.

According to clinical evaluation, 3 patients had T1N0, 7 patients had T2N0, 10 patients had T2N1, 3 patients had T2N2b, 6 patients had T3N1, 2 patients had T3N2a, 6 patients had T3N2b, and 2 patients had T4N2b.

In 37 patients, lymph nodes were metastatic. In all T3 patients metastatic deposits were detected in lymph nodes. Pathologic examination provided analysis of 17 structures of the head and neck, including muscles, tonsils, salivary glands, bones, cartilages and vessels.

Results with each imaging modality

The results of CECT and CTP imaging in the detection of malignant infiltration in the group of 39 patients with head and neck cancer are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The results of CECT and CTP imaging in the detection of malignant infiltration in head and neck structures.

| Structure/space | FN | TP | TN | FP | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrinsic tongue muscles (n=32) | |||||||||

| CECT | 3 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 70 | 81.8 | 78.12 | 63.66 | 85.71 |

| CTP | 0 | 9 | 20 | 1 | 100 | 95.4 | 96.87 | 90.9 | 100 |

|

| |||||||||

| Floor of the mouth muscles (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 2 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 75 | 85.7 | 83.72 | 54.5 | 93.75 |

| CTP | 1 | 8 | 29 | 1 | 90 | 96.9 | 88.37 | 90 | 96.96 |

|

| |||||||||

| Pterygoid muscles (n=21) | |||||||||

| CECT | 2 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 60 | 87.5 | 80.95 | 60 | 87.5 |

| CTP | 0 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 100 | 93.7 | 95.23 | 83.33 | 100 |

|

| |||||||||

| Palatine tonsils (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 3 | 9 | 20 | 7 | 75 | 78.1 | 79.06 | 56.26 | 89.28 |

| CTP | 5 | 8 | 17 | 9 | 61.53 | 73.3 | 69.76 | 50 | 81.48 |

|

| |||||||||

| Lingual tonsil (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 2 | 5 | 30 | 2 | 75 | 94.2 | 90.69 | 75 | 94.28 |

| CTP | 3 | 4 | 27 | 5 | 62.5 | 85.7 | 86.04 | 50 | 90.90 |

|

| |||||||||

| Parotid gland (n=32) | |||||||||

| CECT | 0 | 3 | 25 | 2 | 100 | 93.1 | 93.75 | 60 | 100 |

| CTP | 1 | 2 | 23 | 4 | 66.6 | 86.2 | 84.37 | 33.33 | 96.15 |

|

| |||||||||

| Submandibular gland (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 1 | 6 | 30 | 2 | 87.5 | 94.2 | 93.02 | 77.73 | 97.05 |

| CTP | 1 | 3 | 30 | 5 | 80 | 86.8 | 86.04 | 44.41 | 97.05 |

|

| |||||||||

| Mandible (n=32) | |||||||||

| CECT | 2 | 1 | 29 | 0 | 33.3 | 100 | 93.75 | 100 | 93.51 |

| CTP | 3 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 90.62 | 0 | 90.62 |

|

| |||||||||

| Thyroid cartilage (n=35) | |||||||||

| CECT | 2 | 4 | 28 | 1 | 66.6 | 96.5 | 91.42 | 80 | 93.33 |

| CTP | 4 | 2 | 28 | 1 | 33.3 | 96.5 | 85.71 | 66.6 | 87.5 |

|

| |||||||||

| Carotid space (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 3 | 3 | 29 | 4 | 50 | 89.1 | 83.72 | 42.81 | 91.66 |

| CTP | 1 | 5 | 32 | 1 | 83.3 | 97.2 | 95.34 | 83.3 | 97.28 |

|

| |||||||||

| Prevertebral space (n=39) | |||||||||

| CECT | 1 | 1 | 34 | 3 | 50 | 92.6 | 90.69 | 25 | 97.41 |

| CTP | 0 | 2 | 36 | 1 | 100 | 97.5 | 97.67 | 66.6 | 100 |

Tumors (squamous cell cancer) on PCT revealed high values of BF, BV and PS. The mean value of BF was 112 ml/100 g/min, mean value of BV was 6.4 ml/100 g and mean value of PS was 17.3 ml/100 g/min. In 7 tumors a mismatch was observed between BF and BV. The lowest BV values noted were 2.7 ml/100 g and the lowest BF values noted were 52 ml/100 g.min. Such areas of mismatch were classified as neoplasmatic infiltration.

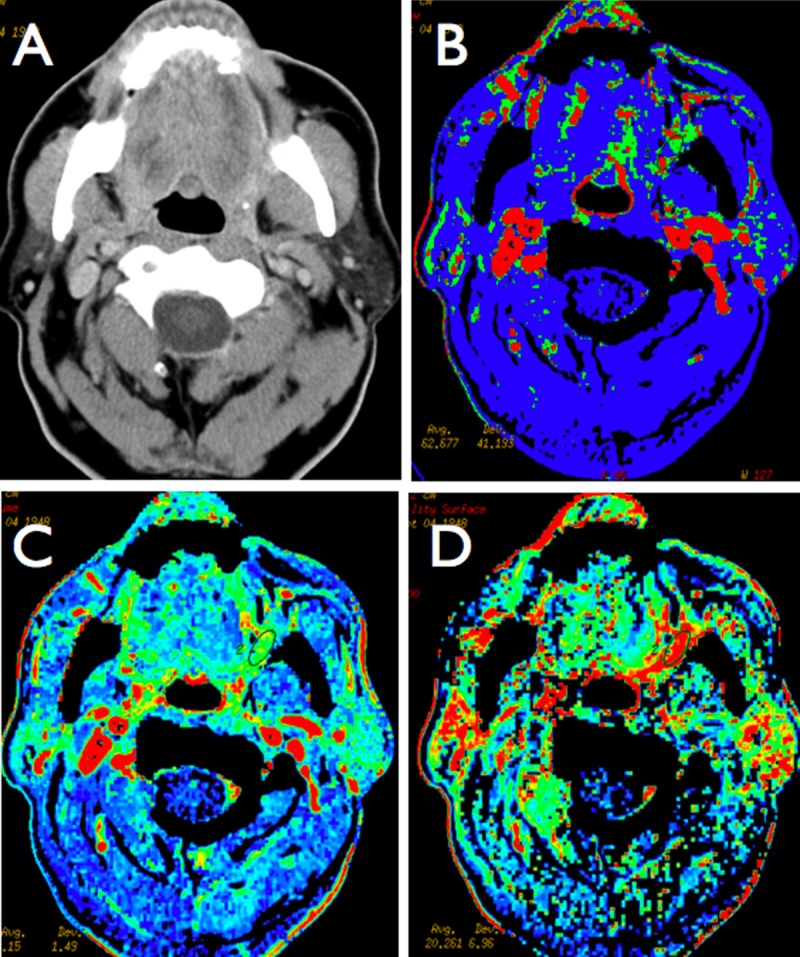

Infiltrated muscles were characterized by high values of BF (101 ml/100 g/min) and BV (6.5 ml/100 g). Characteristic perfusion pattern of infiltration is presented in Figure 2. Non-infiltrated healthy muscles from the contralateral unaffected site had much lower values: BF was 29.1 ml/100 g/min and BV was 3.4 ml/100 g.

Figure 2.

A case of retromolar trigone carcinoma (clinically obvious and visible as mucosal infiltration) with suspected deep infiltration of muscles and oropharynx (A). There is no visible infiltration and pathologic contrast enhancement on CECT study. Perfusion maps demonstrate high values of blood flow (B), blood volume (C) and permeability (D) on the left retromolar area and left tongue, which is suggestive of malignant infiltration. The ROI was placed based on CTP results, where the area of pathologic hyperperfusion was present.

Infiltration was suspected, based on CTP studies, when BF values doubled values from the contralateral side and/or when BV value was at least 50% greater than the value from the contralateral side. The decision on the character of tissue based on BF/BV values was made by 2 radiologists, in consensus.

MTT in the majority of tumors was shortened, but in some was it was prolonged (range from 4.1 s to 11.8 s); as such, it has not been taken into account when deciding on infiltration. PS in all tissues proven afterwards to be infiltrated was at least twice as high compared to the values from contralateral unaffected structures (mean value for infiltrated muscles = 16.8 ml/100 g/min, and mean values for healthy muscles was 7.2 ml/100 g/min).

Malignant infiltration of muscles was correctly identified with CECT with 60–75% sensitivity. This was calculated using histopathology and radiologic-surgical evaluation as the gold standard (see: Materials and Methods – Surgery and Histopathology section for detailed explanation). Findings were false-negative in 7 cases. With CTP studies, it was possible to depict muscles infiltration with 90–100% sensitivity, with false-negative findings only in 1 case. False-negative finding in this case occurred when there was subtle infiltration of mylohyoid muscle very close to the mandible and partial volume effect artefacts appeared.

With regard to tonsils, infiltration was detected with 75% sensitivity with the use of CECT only. Based on CTP images, sensitivity in detecting infiltration was lower and reached a maximum of 62.5%. There were 5 false-negative cases based on CECT and as many as 8 false-negatives based on CTP. In case of infiltration of salivary glands, it was appropriately detected on CECT images (up to 100% sensitivity), where information from CTP was of little, if any help. When describing bone and cartilage infiltration, CECT and CTP were not very helpful, especially in less advanced cases, with specificity ranging from 28% to 29%.

With regard to neck spaces infiltration, CTP examinations were very sensitive, reaching 100% in detecting prevertebral space infiltration. The infiltration of this space was suspected based on CTP parameters of prevertebral muscles. Infiltration of carotid space was suspected based on the presence of malignant tissue within the carotid sheath, directly in contact with the jugular vein and/or carotid artery. Only in 1 case there were radiologic signs of carotid artery invasion.

False-positive results were found mainly in defining possible infiltration of well-perfused structures, like salivary glands and tonsils.

Among all infiltrated structures in all 39 patients, concordant results for infiltration were present mainly in tonsils, salivary glands, bone and cartilage – in these cases CTP did not provide substantial additional information in comparison to CECT. Discordant results for malignant infiltration occurred for muscle, carotid space and prevertebral space.

Discussion

The extent of malignant infiltration, determined as TNM staging, has a major influence on the prognosis of patients with head and neck tumors. Advancement of local disease and especially lymph node metastasis influences not only the risk of local recurrence, but also the risk of distant metastases.

Routine pre-operative assessment includes complete head and neck examination with indirect nasopharyngeal and laryngeal endoscopy, followed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy for cytology or excisional biopsy. Decisions concerning the type and extension of surgery are therefore made based on results of endoscopy and palpation [1]. However, the visible mucosal lesion may represent the “tip of the iceberg” since submucosal spread cannot be defined by clinical examinations alone. It is also known that detection of metastases in lymph nodes of the neck is more accurately performed with imaging rather than palpation; therefore, imaging studies should be routinely used in patients with head and neck cancer [3,4].

Since CT has become the imaging method of choice for most hypopharyngeal and oropharyngeal lesions [2], in the majority of patients it would be the first-line examination. However, based on contrast-enhanced CT studies it is very difficult to differentiate between tumor and accompanying inflammation or slight edema, which usually leads to the upstaging of malignant process, according to some authors [5,6,9].

Computed tomography perfusion quickly became an effective, simple and reliable method for the assessment of pathologic neo-vascularization, which is typical for tumors [5,6,14].

It has recently been suggested that CTP might have the ability to differentiate tumors from normal tissue [7–10,14].

The aim of this study was to search for adjacent tissue infiltration in cases of head and neck malignant tumors, and to compare the different imaging modalities – standard contrast-enhanced CT with functional imaging (perfusion) – for the detection of malignant infiltration, especially when it was not obvious on CECT images. As a result, it might be clear if one technique is better than another; therefore, the strengths and potential pitfalls could be appreciated. This is particularly important because some centers have distinct preferences for a given imaging modality, especially emphasizing perfusion imaging as a new “hot” reliable tool for every clinical quest.

To our knowledge, no published reports have compared the sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of CECT and CTP for the detection of malignant infiltration.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the most frequently used modality for infrahyoid neck tumor staging and is also used for some of suprahyoid neck lesions, although MRI in this case is surely the preferred modality. A sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 92% have been reported for detecting local spread of tumors [4]. This study showed high sensitivity for detecting muscle infiltration, especially with the application of perfusion imaging, reaching 100% and enabling in many cases the detection of pterygoid and extrinsic tongue muscle invasion. However, in cases of tonsils and bone infiltration, both methods revealed very similar sensitivity and negative predictive value. Interestingly, for the evaluation of salivary glands, standard CECT examination was proven to be better than perfusion examination in terms of the detection of infiltration by a carcinoma.

The mechanism behind it may be partially explained in the first perfusion studies performed by Rumboldt, Hermans, Bisdas and Ghandi [7,8,10,11].

In a very interesting study, Rumboldt [7] observed significant difference between malignant lesions and normal neck structures in all perfusion parameters. Malignant areas had higher blood volume, blood flow and permeability. These findings were attributed to the tumor’s neovascularity. This important observation was proven subsequently in further studies of perfusion in head and neck tumors [8,10,12–14]. Rumboldt also noticed that normal salivary glands have a very high blood flow and volume physiologically, and that therefore evaluation of possible malignant infiltration in these structures may not be reliable. These initial observations are consistent with our findings – when evaluating submandibular and sublingual glands, we found it very hard to detect malignant infiltration based on CTP parameters, which was better observed on standard CECT images.

When evaluating bone and cartilage invasion, the reliability of CTP to detect malignant infiltration was very low. This is due to the fact that perfusion parameters in bone and cartilage are very low (due to histologic type of tissue) and even gross bone disturbances in terms of osteosclerosis and osteolysis do not produce noticeable change in any perfusion parameters.

In a very recent study by Faggioni et al. [14], the role of CTP was evaluated with 64-row MDCT. Data from this study showed that CTP could provide useful information for differentiation between SCC and normal tissue. The authors found significantly higher BF and BV values in SCC compared to normal tissue. This finding was attributed to the enlarged neovascular bed as a consequence of tumoral neoangiogenesis. This holds promise for better delineation of the extent of a tumor and for more accurate staging.

In our study we have shown inability to differentiate between healthy and infiltrated tissue based on CTP results in bones. In this tissue, perfusion parameters are very low due to histologic type of tissue, and even gross bone disturbances in terms of osteosclerosis and osteolysis do not produce noticeable change in any perfusion parameters.

This study has some limitations. The number of patients is not particularly high. Also, we did not perform separate analysis of the character of lymph nodes, although PCT values in enlarged lymph nodes were noted.

Conclusions

Evaluation of CTP images clearly improves the depiction of malignant infiltration of muscles, with much better overall results when compared to CECT image analysis. Sensitivity of CTP for the detection of infiltration in bones, tonsils and salivary glands is lower than that of CECT imaging and CT because of either very dense or scant vascularization pattern.

Despite the fact that all imaging modalities may fail to depict small areas of malignant infiltration, and imaging modalities may be unable to distinguish tumor from inflammation, the combined use of CECT and CTP improves staging of head and neck tumors.

Footnotes

Source of support: This study was entirely financed by State Committee for Scientific Research grant number N N 402 352538

References

- 1.Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):489–501. doi: 10.4065/83.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stambuk HE, Karimi S, Lee N, et al. Oral cavity and oropharynx tumors. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah GV, Wesolowski JR, Ansari SA, et al. New directions in head and neck imaging. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:644–48. doi: 10.1002/jso.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conley BA. Treatment of advanced head and neck cancer: what lessons have we learned? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1023–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emonts P, Bourgeois P, Lemort M, et al. Functional imaging of head and neck cancers. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2009;21:212–17. doi: 10.1097/cco.0b013e32832a2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miles K. Tumour angiogenesis and its relation to contrast enhancement on computed tomography. Eur J Radiol. 1999;30:198–205. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rumboldt Z, Al-Okaili R, Deveikis JP. Perfusion CT for head and neck tumours: Pilot Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1178–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermans R, Lambin P, Van der Goten, et al. Tumoural perfusion as measured by dynamic computed tomography in head and neck carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 1999;53:105–11. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dammann F, Horger M, Mueller-Berg M, et al. Rational diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck region: comparative evaluation of CT, MRI, and 18FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(4):1326–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisdas S, Konstantinou GN, Lee PS, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT of head and neck tumors: perfusion measurements using a distributed-parameter tracer kinetic model. Initial results and comparison with deconvolution-based analysis. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52(20):6181–96. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/20/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi D, Chepeha DB, Miller T, et al. Correlation between initial and early follow-up CT perfusion parameters with endoscopic tumor response in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx treated with organ-preservation therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(1):101–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisdas S, Baghi M, Wagenblast J, et al. Differentiation of benign and malignant parotid tumors using deconvolution-based perfusion CT imaging: feasibility of the method and initial results. Eur J Radiol. 2007;64(2):258–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi D, Hoeffner EG, Carlos RC, et al. Computed tomography perfusion of squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: initial results. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:687–93. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faggioni L, Neri E, Cerri F, et al. 64-row MDCT perfusion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: technical feasibility and quantitative analysis of perfusion parameters. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(1):113–21. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czarnecka A, Zimny A, Sąsiadek M. Correlation of CT perfusion and CT volumetry in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Pol Przegl Radiol. 2010;75(2):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimny A, Szewczyk P, Czarnecka A, et al. Usefulness of perfusion-weighted MR imaging in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16(Suppl 1):5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trojanowski P, Klatka J, Trojanowska A, et al. Evaluation of cervical lymph nodes with CT perfusion in patients with hypopharyngeal and laryngeal squamous cell cancer. Pol Przegl Radiol. 2011;76(1):7–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]