Summary

Background

The role of genetic risk factors in ischemic stroke is unclear. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GpIIb-IIIa) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. We sought to evaluate the relationship between the GpIIb/IIIa complex gene polymorphism and ischemic stroke.

Material/Methods

We investigated the association of the GpIIb/IIIa complex gene polymorphism with stroke risk in 306 patients with acute ischemic stroke and 266 control subjects by determining the GpIIb and GpIIIa genotype from leukocyte DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by FokI and ScrFI digestion, respectively.

Results

Compared with controls, more patients presented with coronary heart disease, hypertension, smoking history, and diabetes. In addition, the patients had higher levels of cholesterol and glucose compared with the control subjects. All donors in the GpIIIa (n=572) group expressed the GpIIIa PlA1 (HPA-1 aa) phenotype. There were no significant differences between the HPA-3 genotype (GpIIb) patient distribution (aa=39.9%, ab=41.4%, bb=28.7%) and healthy control subjects (aa=36.1%, ab=35.0%, bb=28.9%) (P=0.580). Among study participants <60 years, there was a significant difference in the HPA-3 genotype distributions of patients (aa=42.9%, ab=19.8%, bb=37.4%) and healthy control subjects (aa=43.3%, ab=38.8%, bb=17.9%) (P=0.007). Furthermore, HPA-3 b/b increased the risk of ischemic stroke >2-fold (P=0.008).

Conclusions

The GpIIb Ile/Ser843 gene polymorphism is associated with ischemic stroke among young and middle-aged adults (<60 years), especially males. The GpIIIa PlA1 phenotype has no relationship to ischemic stroke.

Keywords: platelets, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, polymorphism, ischemic stroke

Background

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability and remains the third most common cause of death in industrialized nations [1]. In the US and Canada, thrombolysis is the only approved therapy during the acute stroke phase [2]; however, thrombolysis therapy has a narrow therapeutic window of 3 hours (up to 6 hours) because intravenous administration of t-PA within 3 hours after the onset of stroke has been shown to increase the probability of a favorable outcome [3]. In the US, fewer than 5% of patients with acute ischemic stroke receive t-PA, primarily because of a delay in hospital presentation, and are outside the 3-hour window [4]. In addition, the limitations of tissue plasminogen activators (t-PA) are well-known [5], and few stroke patients are recommended for this treatment.

Known risk factors for stroke include smoking, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, advanced age, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs12425791 of nerve injury-induced protein-2 gene polymorphism was reported in Chinese Han patients with ischemia stroke [6]. However, the role of genetic risk factors in ischemic stroke remains largely undefined [7]. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GpIIb-IIIa), a membrane receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cerebral infarction. The genes encoding the platelet IIb and IIIa glycoprotein are located on chromosome 17, lying within a 260-kb fragment in the region 17q21 to 22 with GpIIb 3′ to GpIIIa [8]. Several point mutations in the genes that encode GpIIb and GpIIIa result in disorders of platelet binding. Human platelet antigen-3 (HPA-3) (Baka/Bakb) is a common polymorphism of platelet GpIIb, resulting from a thymine (T) to guanine (G) base change coding for an isoleucine-to-serine substitution at position 843 of the GpIIb heavy chain [8]. A transversion or exchange from thymine (T) to cytosine (C) was found at codon 33 of the GpIIIa, resulting in a Leu33 (HPA-1a, PlA1) to Pro (HPA-1b, PlA2) change [9].

Therefore, we carried out a study to evaluate the relationship between the GpIIb/IIIa complex gene polymorphism and ischemic stroke, and to provide a possible basis for preventing and treating ischemic stroke.

Material and Methods

Patients

From May 2008 and June 2010, we recruited patients with acute ischemic stroke who were admitted to the Neurology Department of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China. Patient inclusion criteria were ≥18 years of age, and a clinical diagnosis of primary acute ischemic stroke. Ischemic stroke was diagnosed by a neurologist according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [10] and confirmed by computed tomographic (CT) scan and/or conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. A cerebral CT scan or MRI was performed to exclude patients who had an intracranial hemorrhage. Patient exclusion criteria included other intracranial pathologies (eg, tumor, infection). Control subjects were included if they showed no neurological symptoms, and had no pathological findings on cranial CT or MRI, and if the stenosis of the cervical artery and vertebral artery was <30% by ultrasound examination.

The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board, including the consent procedures, data security processes, and genotyping protocols. This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects or their legal guardians.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Genomic DNA was isolated from 1 mL EDTA anticoagulated blood by protein salting and ethanol extraction of DNA as described by Miller et al. [11]. Oligonucleotide primers selected for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were used to amplify those parts of the genomic DNA that contain the polymorphic sequences corresponding to the HPA-1 and HPA-3 alleles. The HPA-3 polymorphism, which is a substitution of Ile843Ser as a result of a T-to-G change in the GpIIb gene, was detected by PCR amplification of a 253-bp fragment with use of the forward primer (5′-CTC AAG GTA AGA GCT GGG TGG AAG AAA GAC-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-CTC ACT ACG AGA ACG GGA TCC TGA AGC CTC-3′). The HPA-1 polymorphism, which is a substitution of Leu33Pro as a result of a T-to-C change in the GpIIIa gene, was detected by PCR amplification of a 338-bp fragment with use of the forward primer (5′-CTG CAG GAG GTA GAG AGT CGC CAT AG-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-CTC CTC AGA CCT CCA CCT TGT GCT CT -3′) [12].

PCR was performed on 1 μg genomic DNA template in a total volume of 50 μL with 50 pmol of the appropriate primers and 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase. For GpIIb, 40 cycles of PCR were run at 96°C for 90 seconds, 60.5°C for 90 seconds, and 72°C for 3 minutes; for GpIIIa, 37 cycles of PCR were run at 94°C for 50 seconds, 57.5°C for 85 seconds, and 72°C for 110 seconds.

Restriction-enzyme digestion

Restriction-enzyme digestion of the PCR products were performed under conditions recommended by the manufacturers with 4 units FokI (SibEnzyme) and 10 units ScrFI (MBI Fermentas) for determination of HPA-3 and HPA-1 genotype, respectively. For HPA-3, the presence of Ile at position 843 resulted in the cleavage of the 253-bp fragment into a 126- and 127-bp fragment, whereas the presence of Ser was characterized by the uncleaved 253-bp fragment. Genotypes were classified as aa (Ile, Ile), ab (Ile, Ser) and bb (Ser, Ser); for HPA-1, the presence of Leu at position 33 resulted in the cleavage of the 338-bp fragment into a 214-, 46- and 78-bp fragment, respectively, whereas the presence of Pro resulted in the cleavage of the 338-bp fragment into a 77-, 137-, 46- and 78-bp fragment, respectively. Genotypes were classified as aa (Leu, Leu), ab (Leu, Pro) and bb (Pro, Pro) [12]. The PCR products of GpIIb and GpIIIa were analyzed by 1.6% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. The digests were analyzed by 2.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. Fragments were visualized by use of the Multi Genius Bio Imaging System (Dell).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Student’s T test was used to compare differences between groups. Categorical variables were compared by means of the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze all classic risk factors together with the genotype on ischemic stroke. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11.5 software. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study patients and control subjects

A total of 306 patients with ischemic stroke met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study; 266 control subjects were also recruited. Demographic characteristics of the patients and control subjects are presented in Table 1. There were 165 males and 141 females in the stroke patient group and 136 males and 130 females in the control group. The mean age of stroke patients was 69.55±11.36 years (range, 35–96 years) and the mean age of control subjects was 67.89±7.11 years (range, 42–97 years). No statistically significant difference was observed between the 2 groups. Compared with controls, more patients presented with coronary heart disease, hypertension, smoking history, and diabetes. In addition, patients had higher levels of cholesterol and glucose compared with the control subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants with acute ischemic stroke and healthy control subjects.

| Patients | Control subjects | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 69.55±11.36 | 67.89±7.11 | 0.192 |

| SBP, mmHg | 143.61±15.78 | 134.17±20.18 | 0.003 |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.84±8.48 | 83.32±10.28 | 0.270 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.23±0.84 | 4.81±1.14 | 0.002 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 1.67±0.82 | 1.53±0.91 | 0.183 |

| Glu, mmol/L | 6.54±2.12 | 5.68±1.57 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 199 (65.0%) | 85 (32.0%) | 0.000 |

| CAD, n (%) | 88 (28.8%) | 32 (12.0%) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 59 (19.3%) | 16 (6.0%) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 221 (72.2%) | 107 (40.2%) | 0.000 |

CAD – coronary artery disease; DBP – diastolic blood pressure; Glu – glucose; SBP – systolic blood pressure; TGs – triglyceride.

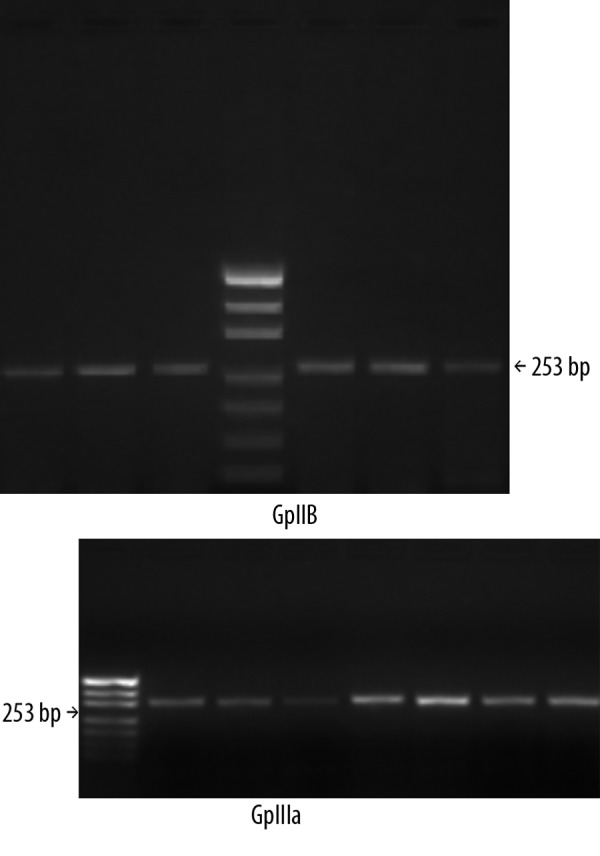

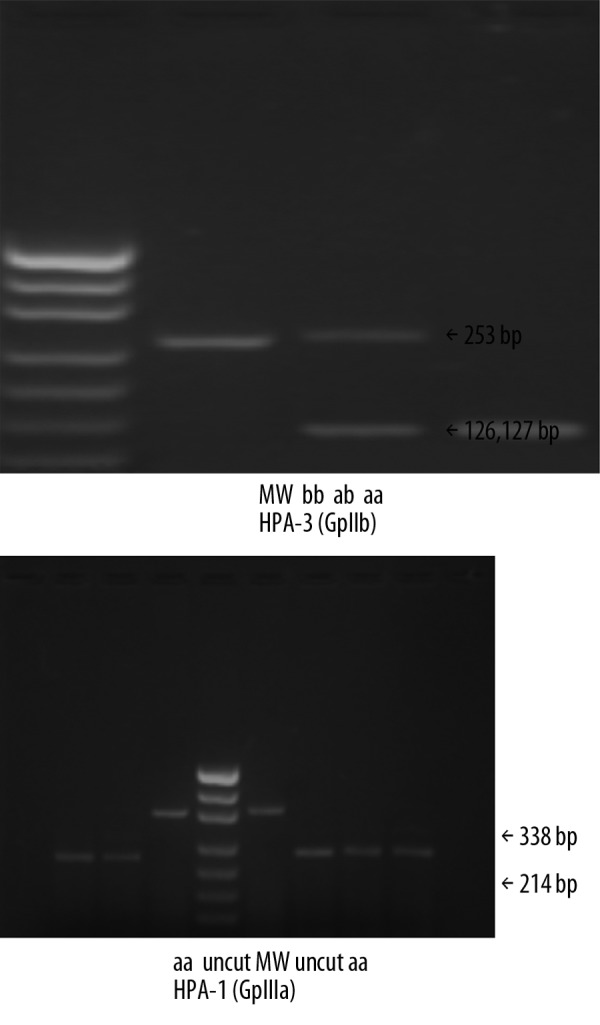

The patterns of enzyme-digested PCR products of GpIIb or GpIIIa gene

The PCR products for a portion of the GpIIb and GpIIIa genes generated from genomic DNA of different individuals are shown in Figures 1 and 2. For the HPA-3(aa) phenotype, the 2 fragments after cleavage differed so little that they appeared as a single band in the gel. For the HPA-1 system, the expected fragments of 46 bp and 78 bp were too low in weight to be reliably detected by gel electrophoresis. All donors in the GpIIIa (n=572) expressed the GpIIIa PlA1 (HPA-1 aa) phenotype. These results were confirmed by subsequent sequencing of the PCR product.

Figure 1.

PCR products of GpIIb and GpIIIa DNA, pUC19 (MspI) fragments were used as standard. Analysis was performed on 1.6% agarose gel.

Figure 2.

Analysis of HPA-1 and HPA-3 by PCR-RFLP using ScrFI and Fok I endonuclease respectively, on 2.2% agarose gel. pUC19 (MspI) fragments were used as molecular weight (MW) standards.

The genotype between the patients and the control subjects

There were no significant differences in the HPA-3 genotype distributions of patients (aa=39.9%, ab=41.4%, bb=28.7%) and healthy control subjects (aa=36.1%, ab=35.0%, bb=28.9%) (P=0.580, Table 2).

Table 2.

The genotype of HPA-3 between the patients and the control subjects.

| aa | ab | bb | X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n,%) | 122 (39.9%) | 96 (31.4%) | 88 (28.7%) | 1.090 | 0.580 |

| Control subjects (n,%) | 96 (36.1%) | 93 (35.0%) | 77 (28.9%) |

The genotype between patients and control subjects with age under 60 years

Because age has been shown to influence the incidence of ischemic stroke, we further analyzed the clinical and genotyping data in study patients with acute ischemic stroke and healthy control subjects who were <60 years. The 2 groups showed no statistically significant difference in age, cholesterol, and glucose levels except that the ischemic stroke patients had significantly higher levels of triglycerides (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of study participants with acute ischemic stroke and healthy control subjects (age <60 years).

| Patients (n=91) | Control subjects (n=67) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.55±7.36 | 52.27±4.62 | 0.697 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134.32±16.92 | 129.18±12.41 | 0.258 |

| DBP, mmHg | 82.95±10.31 | 77.05±11.38 | 0.078 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.98±1.14 | 5.03±0.78 | 0.865 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 2.01±0.91 | 1.25±0.64 | 0.003 |

| Glu, mmol/L | 6.29±2.24 | 5.25±1.59 | 0.083 |

| Smoking | 57 (62.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | 0.870 |

| CAD, n (%) | 16 (17.6%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.376 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 11 (12.1%) | 6 (9.0%) | 0.610 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 28 (30.8%) | 19 (28.4%) | 0.860 |

CAD – coronary artery disease; DBP – diastolic blood pressure; Glu – glucose; SBP – systolic blood pressure; TGs – triglyceride.

There was a significant difference in the HPA-3 genotype distributions of patients (aa=42.9%, ab=19.8%, bb=37.4%) and healthy control subjects (aa=43.3%, ab=38.8%, bb=17.9%) (P=0.007, Table 4).

Table 4.

The genotype distribution of HPA-3 between patients and control subjects (age <60 years).

| aa | ab | bb | X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n,%) | 39 (42.9%) | 18 (19.8%) | 34 (37.4%) | 10.033 | 0.007 |

| Control Subjects (n,%) | 29 (43.3%) | 26 (38.8%) | 12 (17.9%) |

In a logistic regression model comparing ischemic stroke patients to control subjects aged <60 years, the HPA-3 b/b genotype was significantly associated with ischemic stroke (P=0.000). We further found that the presence of HPA-3 b/b significantly increased the risk of ischemic stroke >2-fold (P=0.008, Table 5).

Table 5.

The genotype (aa+ab) and bb of HPA-3 between patients and control subjects (age <60 years).

| Patients (n,%) | Control subjects (n,%) | X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aa+ab (n,%) | 57 (62.6%) | 55 (82.1%) | 7.075 | 0.008 |

| bb (n,%) | 34 (37.4%) | 12 (17.9%) |

In addition, the HPA-3 b/b genotype might be a stronger risk factor for stroke among males (P=0.032) compared with females (P=0.184). As to the genotype (aa+ab) and bb in males, the presence of HPA-3 b/b increased the risk of ischemic stroke >2-fold (OR=2.194, 95%CI 1.177~4.091).

Discussion

Platelets play an important role in the pathogenesis of thromboembolic diseases, and the possibility of inherited platelet risk factors for acute thrombosis is intriguing and especially important in assessing clinical risk and in prophylactic and therapeutic interventions. Platelet thrombosis is mediated by several platelet membrane receptor complexes, including glycoprotein Ib/IX, glycoprotein Ia/IIa, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa [13]. GpIIb/IIIa, the Ca2+-dependent receptor for fibrinogen on the surface of platelets, which consists of αIIb subunits (GpIIb) and β3 subunits (GpIIIa), is the platelet integrin thought to mediate the fibrinogen-dependent common pathway of platelet aggregation [14]. The platelet GpIIb/III receptors play an important role in thrombus formation.

Carlsson et al. demonstrated that the HPA-1b genotype was slightly more frequent in patients than in healthy blood donors [15]. In a rather small and limited study, GpIIb/IIIa PlA1/A2 polymorphism was shown to be associated with atherothrombotic stroke in young patients [16] and in young white women [17]. Some studies indicate that there was a smoking-by-genotype association with the risk of lacunar infarcts and with survival. Among younger (55 to 69 years) stroke patients, smokers carrying the PlA2 allele were at a higher risk (P=0.024) of lacunar infarcts than were non-carrier smokers [18]. One study suggested that homozygosity for the HPA-1b (P<0.001) alleles was more prevalent in stroke patients than in control subjects [19]. Our study showed that there were no significant differences between patients and the control subjects for the aa, ab, and bb of HPA-3 genotypes (P=0.580).

Previous studies indicated that various risk factors related with ischemic stroke include smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, transthoracic echocardiographic abnormalities, and advanced age [18,20]. Hence, we further analyzed patients with acute ischemic stroke who were <60 years for a comparison according to the World Health Organization definition of the elderly. The present results indicated that in this patient subgroup, the genotype (P=0.007) and triglycerides (P=0.003) between the patients and the control subjects were statistically significantly different. The HPA-3 b/b genotype in patients was significantly higher than in control subjects (P=0.008). The HPA-3 b/b genotype was a stronger risk factor for ischemic stroke among males (P=0.032) than females (P=0.184). As for the HPA-1 system, all donors expressed the GpIIIa PlA1 (HPA-1 a/a) phenotype, suggesting that the GpIIIa PlA1 phenotype has no relationship with cerebral infarction in Chinese patients. The HPA-3 b/b genotype was significantly associated with ischemic stroke.

Drugs that inhibit platelet function are widely used to decrease the risk of arterial occlusion in patients with atherosclerosis. There are 3 families of anti-platelet agents with proven clinical efficacy: (1) cyclooxygenase inhibitors, such aspirin; (2) adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonists, such as ticlopidine and clopidogrel; and (3) glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists. Antagonists of platelet membrane GpIIb/IIIa inhibit the final common step in platelet aggregation, which involves the binding of adhesive proteins to GpIIb/IIIa or integrin αIIbβ3, which is essential for platelet-to-platelet bridging. GpIIb/IIIa antagonists that are available for clinical use are: (1) abciximab, a humanized murine monoclonal antibody IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist; (2) 2 non-peptide compounds, tirofiban and lamifiban; and (3) eptifibatide, a peptide based on a snake venom sequence and presumably a mimetic of the r-chain peptide of fibrinogen [21]. Some research has shown that GpIIb/IIIa antagonists had no positive effect on stroke size and functional outcome, but increased the incidence of ischemic cerebral hemorrhage [22]; however, other studies have shown that the combination of a thrombolytic and a GpIIb/IIIa antagonist may have a synergistic effect on recanalization efficiency, which may improve clinical outcome and lower the risk of ischemic cerebral hemorrhage [23]. In patients with acute ischemic stroke, a dose-escalation study demonstrated that the GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab is safe when given as a 0.25 mg/kg bolus and 0.125 mg/kg/min infusion. The Emergent Stroke Treatment Trial (ABESTT) study suggested that compared with rt-PA given within a 3-hour window, abciximab may be more effective and had a better safety profile in treating acute stroke [24,25]. Systemic combined thrombolysis with rtPA and tirofiban seems to be a feasible treatment in acute stroke [26]. In the EPIC study, there was no difference in the occurrence of hemorrhagic or non-hemorrhagic strokes between patients treated with abciximab or placebo [27,28]. A more recent study examining polymorphism of the human thromboxane synthase (CYP5A1) gene in stroke patients indicated that allelic prevalence of the CYP5A1 exon 12 might be associated with particular characteristics of stroke patients [29]. It is obvious that ischemic stroke is a heterogeneous disease, and a single approach to treatment will necessarily fail in some patients. Hence, a patient-specific individualized medicine approach or combining a variety of drugs, each chosen based on the patient’s likely mechanism of stroke, may increase the chance of recanalization.

One limitation of our study was that we did not investigate the treatment effects of different genotypes for ischemic stroke patients, which will be addressed in our future studies. Our study suggests that more research should be carried out on GpIIb/IIIa receptor antagonist, especially GpIIb antagonist, for ischemic stroke in young and middle-aged patients.

Conclusions

We found that platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa polymorphism HPA-3 b/b is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients younger than 60 years of age.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2010 Update. A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams HP, Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation. 2007;115(20):e478–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padma S, Majaz M. Intra-arterial versus intra-venous thrombolysis within and after the first 3 hours of stroke onset. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(3):303–15. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simsek S, Faber NM, Bleeker PM, et al. Determination of human platelet antigen frequencies in the Dutch population by immunophenotyping and DNA(allele-specific restriction enzyme) analysis. Blood. 1993;81:835–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingall TJ. Intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: time is prime. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2264–65. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang RX, Zhang J, Liu Y, et al. Relationship between nerve injury-induced protein gene 2 polymorphism and stroke in Chinese Han population. Biomedical Res. 2011;25:11–14. doi: 10.1016/S1674-8301(11)60039-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips DR, Charo IF, Parise LV, et al. The platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa complex. Blood. 1988;71:831–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter AM, Catto AJ, Bamford JM, et al. Association of the platelet glycoprotein IIb HPA-3 polymorphism with survival after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:2606–11. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nurden AT. Polymorphisims of human platelet membrane glycoproteins: structure and clinical significance. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:345–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatano S. Experience from a multicentre stroke register: a preliminary report. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54(5):541–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. Simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unkelbach K, Kalb R, Santoso S, et al. Genomic RFLP typing of human platelet alloantigens Zw(PlA), Ko, Bak and Br (HPA-1,2,3,5) Br J Haematol. 1995;89:169–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb08925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiner AP, Kumar PN, Schwartz SM, et al. Genetic variants of platelet glycoprotein receptors and risk of stroke in young women. Stroke. 2000;31:1628–33. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ofosu FA, Nyarko KA. Human platelet thrombin receptors – roles in platelet activation. Hematology. 2000;14:1185–98. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlsson LE, Greinacher A, Spitzer C, et al. Polymorphisms of the human platelet antigens HPA-1, HPA-2, HPA-3, and HPA-5 on the platelet receptors for fibrinogen (GPIIb/IIIa), von Willebrand factor (GPIb/IX), and collagen (GPIa/IIa) are not correlated with an increased risk for stroke. Stroke. 1997;28(7):1392–95. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.7.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cater AM, Catto AJ, Bamford JM, et al. Platelet GP IIIa PlA and GP Ib variable number tandem repeat polymorphisms and markers of platelet actibation in acute stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1124–31. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.7.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner KR, Giles WH, Johoson CJ, et al. Platelet glycoprotein receptor IIIa polymorphism PlA2 and ischemic stroke risk: the Stroke Prevention in Young Women Study. Stroke. 1998;29:581–85. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niku KJ, Maarit H, Jussi M, et al. Smoking and the platelet fibrinogen receptor glycoprotein IIb/IIIa PlA1/A2 polymorphism interact in the risk of lacunar stroke and midterm survival. Stroke. 2007;38:50–55. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251719.59141.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saidi S, Mahjoub T, Slamia LB, et al. Polymorphisms of the human platelet alloantigens HPA-1, HPA-2, HPA-3, and HPA-4 in ischemic stroke. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(7):570–73. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harshad A, Wilbert SA, Paul L, et al. Prevalence of transthoracic echocardiographic abnormalities in patients with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(1):40–42. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cattanen M. Haemorrhagic stroke during anti-platelet therapy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25(Suppl 42):12–15. doi: 10.1017/S0265021507003213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christoph K, Miroslava P, Mirko P, et al. Targeting platelets in acute experimental stroke. Circulation. 2007;115:2323–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alex AC, Christopher TB, Derk WK, et al. Multimodal therapy for the treatment of severae ischemic stroke combining GpIIb/IIIa antagonists and angioplasty after failure of thrombolysis. Stroke. 2005;36:2286–88. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000179043.73314.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srivastava P, Moonis M. Intra-arterial versus intra-venous thrombolysis within and after the first 3 hours of stroke onset. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(3):303–15. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abciximab Emergent Stroke Treatment Trial Investigators. Emergency administration of abciximab for treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke: results of a randomized phase 2 trial. Stroke. 2005;36:880–90. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157668.39374.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seitz RJ, Hamzavi M, Junghans U, et al. Thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and tirofiban in stroke: preliminary observations. Stroke. 2003;34(8):1932–35. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000080535.61188.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.EPIC Investigators. Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in high-risk coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:956–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404073301402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguirre FV, Topol EJ, Ferguson JJ, et al. Bleeding complications with the chimeric antibody to platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa integrin in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. EPIC Investigators. Circulation. 1995;91:2882–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.12.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimouli M, Gourvas V, Konstantoudaki X, et al. The effect of an exon 12 polymorphism of the human thromboxane synthase (CYP5A1) gene in stroke patients. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(1):BR30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]