Summary

Background

To date, Kaposi sarcoma has not been mentioned among the adverse effects of triptolide/tripdiolide, ethyl acetate extracts or polyglycosides of the Chinese herbal remedy Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F.

Case Report

A patient was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at the age of 29 years. She underwent treatment with corticosteroids, methotrexate and gold sodium thiosulfate, and was chronically taking ketoprofen. At the age of 59 years she started to take a powder (≈2 g/day) from a Chinese physician for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. This powder was supplied to her regularly for 10 years. At the age of 69 years, multiple soft, violaceous to dark-red patches, plaques, nodules and blisters of varying sizes appeared on a background of severely edematous skin on her legs, and later on her arms. Biopsy specimens of the leg lesions were diagnostic for human herpesvirus 8-associated Kaposi sarcoma. Triptolide (235 μg/1 g) and tripdiolide were found in the Chinese powder by the use of Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Administration of the powder was stopped and medication with paclitaxel was introduced. General condition of the patient improved and skin lesions diminished significantly.

Conclusions

This case indicates a possible association between triptolide/tripdiolide chronic intake and development of human herpesvirus 8-associated Kaposi sarcoma. Triptolide/tripdiolide could contribute to development of Kaposi sarcoma by reactivation of latent human herpesvirus 8, permitted by immunosuppression induced by triptolide.

Keywords: Kaposi sarcoma, tryptolide, rheumatoid arthritis

Background

Our aim is to show a case of disseminated cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma (KS), occurring during a long-term usage of a powder containing triptolide/tripdiolide, for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Triptolide and tripdiolide, compounds originally purified from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F[1] and used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine to treat RA [2–4], could contribute to development of KS by reactivation of latent human herpes virus 8 (HHV8), permitted by triptolide-induced immunosuppression [5]. To date, KS has not been mentioned among adverse effects of triptolide, ethyl acetate extracts or polyglycosides of the Chinese herbal remedy Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F[4,6–9], although dermal reactions including different kinds of rush with the tendency to develop erosion and scarring were described with incidence of 55.5% during 12 weeks of treatment with polyglycosides of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F[9].

Case Report

A patient was diagnosed to have RA when she was 29 years old. Since 55 year of age the patient was regularly controlled by a nephrologist due to infections of the urinary tract resulting in chronic tubulo-interstitial nephritis, and due to possible RA influence on kidneys. Serum creatinine was 90–150 μmol/L (normal range 60–90 μmol/L for women).

Since 62 year of age she started to have swollen ankles. Echocardiography was normal, proteinuria was not present, and glomerular filtration rate was over 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 body surface area. A cyst (diameter 20 mm) was shown in the left kidney, not confirmed in further evaluations. Amyloid deposits were not found in the gingival biopsy. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was 4.2 mg/L (normal value <5 mg/L). Medication with chloroquine diphosphate was added to ketoprofen (Table 1), but did not influence ankle edema and joint pain.

Table 1.

Long-term medication of the patient.

| Year of age | Medication |

|---|---|

| 29–56 | Corticosteroids, gold sodium thiosulfate (two courses), methotrexate |

| 56–70 | Long-acting ketoprofen |

| 59–70 | Triptolide (confidential self-administration) |

| 62 | Chloroquine diphosphate |

| 70–71 | Corticosteroids, paclitaxel |

When the patient was 66 years old, petechia appeared on both legs. Doppler ultrasonography of leg vessels was normal. Echocardiography showed mild valvular disease and moderate diastolic left ventricular dysfunction. Proteinuria did not occur, and serum creatinine concentration was maintained between 113 and 168 μmol/L. The dermatological diagnosis was vasculitis. Serum perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative.

Since 69 years of age, leg edema was worse and she stopped working in her profession (a pharmacist). Doppler ultrasonography of leg vessels again did not reveal abnormalities, proteinuria was not present, and renal function was normal. Six months later, multiple soft, violaceous to dark-red patches, plaques, nodules and blisters of varying sizes started to appear on a background of edematous skin on her legs. After disruption, there were long-lasting ulcerations with bloody exudation. She was examined by dermatologists and by rheumatologists, but diagnosis was not made. She became very weak and stayed in bed at home. Ambulatory laboratory data of the blood revealed hemoglobin level of 5.87 mmol/L (normal range 7.44–9.92 g/L for women), total protein of 55.2 g/L (normal range 60–80 g/L), albumin of 27.4 g/L (normal range 35–50 g/L) and creatinine of 144 μmol/L. Proteinuria was not present. Although there was no infection of the urinary tract and renal function was deteriorated no more then before appearance of skin changes, she was admitted to the nephrologic ward to determine her health problem.

At the admission, severe skin lesions on the edematous background were present on the patient’s legs (Figure 1) and incipient skin changes on her arms. Rheumatoid factor (RF) was 2,310 IU/mL (normal range <14 IU/mL), but decreased to 566 IU after introduction of treatment with corticosteroids. Functional class III/IV of RA was classified according to Steinbrocker et al. [10]. Leukocyte count was 3.7 G/L (normal range 4.0–10.8 G/L) and lymphocytes constituted 22% of all leukocytes (normal range 20–44%). Lymphocyte subset percentage was abnormal: CD3 84.0% (normal range 67–76%), CD3+DR+ 43.0% (normal range 8–15%), CD4 32% (normal range 38–46%), CD8 52% (normal range 31–40%), CD19 2% (normal range 11–16%), NK 6% (normal range 10–19%). The patient tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The histological examination of 2 biopsy specimens of the leg lesions showed a mixed proliferation of irregular slit-like vascular channels associated with pleomorphic spindle cells, a low-grade lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes consistent with a diagnosis of KS (Figure 2). Immunophenotypic analysis showed cell markers F VIII+, CK AE1/AE3−, CD34+ and CD31+ (Figure 3), demonstrating the endothelial nature of the proliferating tumor cells. Expression of the proliferative antigen Ki-67 was shown in 20% (specimen 1) and in 30% (specimen 2) of cell nuclei; p53 immunoreactivity was found in less than 5% of cell nuclei. HH8 latent nuclear antigen protein was detected in biopsy specimens by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4). The diagnosis of HH8 KS was made.

Figure 1.

Skin changes on the edematous background shown at the admission to the hospital: (A) on the external part of the foot, (B) on the sole and foot fingers, (C) on the 1/3 lower part of the shank and foot dorsum.

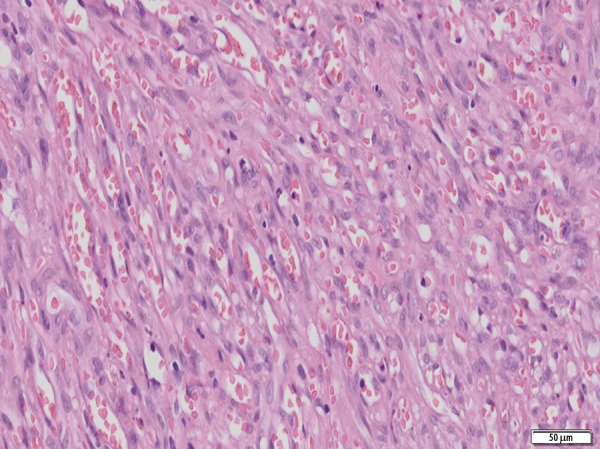

Figure 2.

Fascicles of mildly atypical spindle cells forming slit – like vascular spaces containing extravasated red blood cells. The histological picture is consistent with Kaposi sarcoma (obj. 20×).

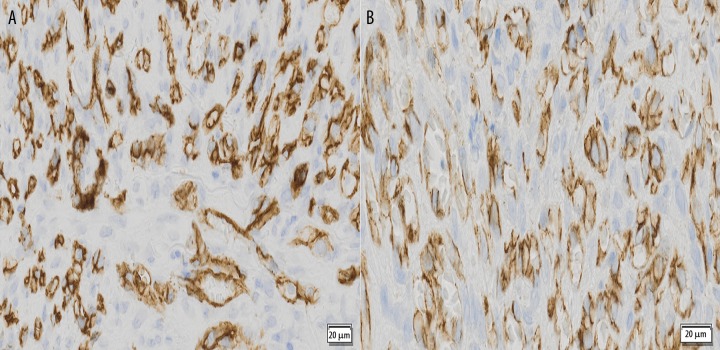

Figure 3.

Positive CD 34 (A) and CD 31 (B) immunostaining of spindle cells (obj. 40×).

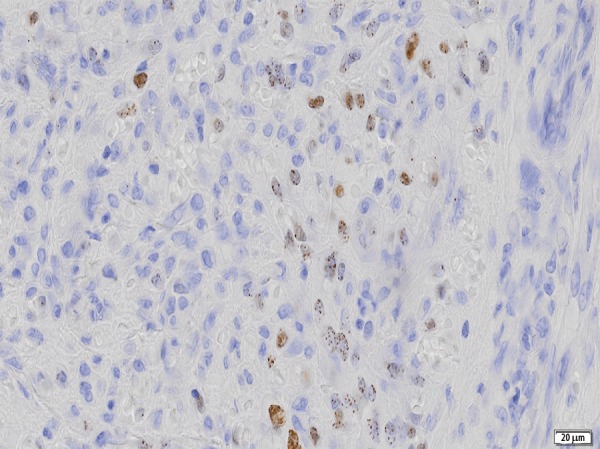

Figure 4.

Herpes virus 8 (HH8) latent nuclear antigen protein detected in biopsy specimen by immunohistochemistry (obj. 40×).

Knowing the diagnosis of HH8 KS, a patient’s spouse confessed that at the age of 59 years she started to take a Chinese powder of unknown composition and continued it until the current hospitalization. She evaluated this powder as a good pain reliever and was convinced that it would help her to avoid severe RA signs and symptoms. According to the patient’s spouse, she used to take 1 dose of powder a day, and sporadically took 2 doses per day. For brief intervals she would stop taking the powder. He calculated that his wife had taken approximately 300 doses per year.

During hospitalization in the nephrologic ward, administration of the powder was stopped. The patient was transferred to the oncological ward and treatments with paclitaxel (Sindaxel, Sindan, Romania) were initiated according to earlier promising reports [11,12]. Paclitaxel was given intravenously in the dose of 100 mg every 2 weeks. Sixteen weeks after withdrawal of the Chinese powder and after 12 weeks of paclitaxel administration (6 doses of paclitaxel were given) the patient’s condition improved and the skin lesions diminished significantly, presenting postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and crust (Figure 5). At the 10th month of treatment with paclitaxel, she died at the age of 71.3 years due to sepsis complicating perforation of the sigmoid diverticulum.

Figure 5.

Improvement in skin changes and smaller leg edema after withdrawal of triptolide and 2.5-month treatment with paclitaxel.

An analysis of the powder

We have suspected that the powder could contain compounds of Trypterigium wilfordii Hook. F., especially triptolide. We obtained a sample of the powder from the patient’s spouse and performed an analysis.

Qualitative examination was done using Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (LC/ESI-MS) system [13]. The presence of triptolide m/z=359 (M-H−) and tripdiolide m/z=375 (M-H−), 2 major active components of Trypterigium wilfordii Hook F, was confirmed. The content of triptolide in 1 g of the analyzed sample, determined by HPLC quantitative analysis, was 235 μg.

Discussion

A question arises how triptolide/tripdiolide, taken in the high daily dose [4] for years, could influence the patient’s health status.

Triptolide is a small molecule known to act as an anti-inflammatory [14] and anti-cancer [15] compound. Its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant activities are used in the treatment of RA [4]. AA amyloidosis, present in 4.44% of early RA patients [16], was shown to be inhibited in mice by experimental treatment with triptolide [17]. About 40 years had passes since diagnosis of RA in the examined patient. Joint surgery was never indicated. Amyloidosis was not detected, at least up to 62 year of age. Thus, progression of RA seemed to be slower than usually observed [18], independently of triptolide/tripdiolide administration. However, only while receiving triptolide/tripdiolide was she almost free from joint pain.

The most important point to determine is the possible association of KS with triptolide/tripdiolide medication. KS is a multifocal angioproliferative neoplasm of the skin (mainly affecting the skin of the limbs) and mucosa, frequently seen in immunosuppressed patients [19], also due to RA [12,20]. HHV8 is the infectious cause of this neoplasm. Over 95% of KS lesions, regardless of their source or clinical subtype, have been found to be infected with HHV8 [21]. HHV8 latent transcripts, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen, viral cyclin, viral FLIP and viral-encoded microRNAs, drive cell proliferation and prevent apoptosis, whereas HHV8 lytic proteins such as viral G protein-coupled receptor, K1 and virally encoded cytokines (viral interleukin-6 and viral chemokines) contribute to the angioproliferative and inflammatory KS lesions through a mechanism called paracrine neoplasia [22]. In patients infected with HIV, KS is associated with a low CD4 lymphocyte count [23–25]. Expression of the proliferative antigen Ki-67, shown in our patient in 20–30% of cell nuclei, does not correlate with skin and organ lesions [26] or early- and late-stage KS lesions [27], but is valuable in KS diagnosis. Triptolide has immunosuppressant activity [28]. Decreasing CD4 cells [29], triptolide could contribute to development of KS by reactivation of latent HHV8, permitted by triptolide-induced immunosuppression [5]. On the other hand, triptolide is an anti-cancer compound [15,30] and KS is not mentioned among the adverse effects of triptolide, ethyl acetate extracts or polyglycosides of the Chinese herbal remedy Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F[4,6–9]. Moreover, KS lesions are attributed to the release of angiogenic molecules, most notably vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [31,32] and angiopoietin-like 4 [33]. Inhibition of VEGF expression and production by triptolide was documented [34]. It was recently found that the antitumor action of triptolide is partly via inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by blocking 2 endothelial receptor-mediated signalling pathways, and triptolide can be a promising antiangiogenic agent [35]. Thus, triptolide as an immunosuppressant could contribute to development of KS, but also could potentially be helpful by VEGF inhibition. However, there is no data on triptolide administration in KS.

Conclusions

Although we cannot definitively answer the question of whether triptolide/ tripdiolide contributed to development of KS in our patient, we also cannot exclude such a possibility. The case of our patient indicates an association between triptolide/tripdiolide chronic intake and development of HHV8 KS. Triptolide/ tripdiolide could contribute to development of KS by reactivation of latent HHV8, permitted by immunosuppression induced by triptolide. We believe that this case will help other physicians to be vigilant for a possible association between KS and medication with Chinese remedies containing triptolide.

Footnotes

This case study was selected for presentation at the 11th Seminar on Advances in Nephrology and Arterial Hypertension in Katowice, 24–26.11.2011

Source of support: Grants from Karol Marcinkowski University of Medical Sciences (nr 502-01-02225363-03679, nr 502-01-0309419-02030)

References

- 1.Kupchan SM, Court WA, Dailey RG, Jr, et al. Triptolide and tripdiolide, novel antileukemic diterpenoid triepoxides from Tripterygium wilfordii. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:7194–95. doi: 10.1021/ja00775a078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu CF, Lin N. Progress in research on mechanisms of anti-rheumatoid arthritis of triptolide. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2006;31:1575–79. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su D, Song Y, Li R. Comparative clinical study of rheumatoid arthritis treated by triptolide and an ethyl acetate extract of Tripterygium wilfordii. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1990;10:144–46. 131. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tao X, Cush JJ, Garret M, Lipsky PE. A phase I study of ethyl acetate extract of the chinese antirheumatic herb Tripterygium wilfordii hook F in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2160–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudderidge TJ, Khalifa M, Jeffery R, et al. Donor-derived human herpes virus 8-related Kaposi’s sarcoma in renal allograft ureter. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:221–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitzen JJ, de Jonge MJ, Lamers CH, et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of F60008, a novel apoptosis inducer, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1764–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Jin H, Li C, Hou Y, et al. Heat shock protein 72 protects kidney proximal tubule cells from injury induced by triptolide by means of activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. Int J Toxicol. 2009;28:177–89. doi: 10.1177/1091581809337418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Jiang Z, Liu J, et al. Sex differences in subacute toxicity and hepatic microsomal metabolism of triptolide in rats. Toxicology. 2010;271:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao XL, Sun Y, Dong Y, et al. A prospective, controlled, double-blind, cross-over study of tripterygium wilfodii hook F in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Chin Med J (Engl) 1989;102:327–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinbrocker O, Traeger CH, Batterman RC. Therapeutic criteria in rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1949;140:659–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.1949.02900430001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osawa R, Kato N, Yanagi T, Yamane N. Clearance of recurrent, classical Kaposi’s sarcoma using multiple paclitaxel treatments. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:435–36. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SY, Jo YM, Chung WT, et al. Disseminated cutaneous and visceral Kaposi sarcoma in a woman with rheumatoid arthritis receiving leflunomide. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(4):1065–68. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou Yang XK, Jin MC, He CH. Simultaneous determination of triptolide and tripdiolide in extract of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. by LC–APCI-MS. Chromatogr. 2007;65:373–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matta R, Wang X, Ge H, et al. Triptolide induces anti-inflammatory cellular responses. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:267–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo Y, Shi C, Liao M. Advance in the anti-tumor mechanism of triptolide. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2009;34:2024–26. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benucci M, Maniscalchi F, Manfredi M. Secondary amyloidosis complicated rheumatoid arthritis, prevalence study in Italian population. Recenti Prog Med. 2007;98:16–19. [in Italian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui D, Hoshii Y, Kawano H, et al. Experimental AA amyloidosis in mice is inhibited by treatment with triptolide, a purified traditional Chinese medicine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1232–40. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindqvist E, Saxne T, Geborek P, Eberhardt K. Ten year outcome in a cohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: health status, disease process, and damage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:1055–59. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.12.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penn I. Kaposi’s sarcoma in immunosupressed patients. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1983;12:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Mahanuphab P, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32:326–33. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707–19. doi: 10.1038/nrc2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TG, Lee KH, Oh SH. Skin disorders in Korean patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus and their association with a CD4 lymphocyte count: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1476–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gantt S, Kakuru A, Wald A, et al. Clinical presentation and outcome of epidemic Kaposi sarcoma in Ugandan children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:670–74. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clifford GM, Franceschi S. Cancer risk in HIV-infected persons: influence of CD4(+) count. Future Oncol. 2009;5:669–78. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozen O, Bilezikçi B, Celasun B, Demirhan B. Ki-67 proliferation index in Kaposi’s sarcoma after renal transplantation: findings in skin-only cases versus cases with internal-organ involvement. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2190–94. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Thier F, Simonart T, Hermans P, et al. Early- and late-stage Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions exhibit similar proliferation fraction. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:25–27. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun S, Wang Y, Zhou Y. Research progress on immunosuppressive activity of monomers extracted from Chinese medicine. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2010;35:393–96. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XH, Zhang ZY. Effect of tripterygium polyglucoside on T-lymphocyte subsets and serum interleukin-5 level in asthma patients. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2001;21:25–27. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong X, Zheng S, Jin J, et al. Triptolide inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human colon cancer and leukemia cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2007;39:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masood R, Cai J, Zheng T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is an autocrine growth factor for AIDS-Kaposi sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akula SM, Ford PW, Whitman AG, et al. B-Raf-dependent expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-A in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected human B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4516–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma T, Jham BC, Hu J, et al. Viral G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates Angiopoietin-like 4 promoting angiogenesis and vascular permeability in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14363–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001065107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu KB, Liu ZH, Liu D, Li LS. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and production by triptolide. Planta Med. 2002;68:368–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-26737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He MF, Huang YH, Wu LW, et al. Triptolide functions as a potent angiogenesis inhibitor. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:266–78. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]