Summary

Background

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) allows for examining brain functions in vivo in schizophrenic patients. Correlations between N-acetylaspartate (NAA) level in the frontal lobe and cognitive functions and clinical symptoms have been observed. The aim of the present study was evaluation of relationship between clinical symptoms, cognitive outcomes and brain function in 1H MRS measures in schizophrenic patients.

Material/Methods

The study included a group of 47 patients with chronic schizophrenia. Patients were assessed by means of PANSS, CGI, and a battery of cognitive tests: WCST, TMT, and verbal fluency test. MRI and MRS procedures were performed. Regions of interest were located in the left frontal lobe, temporal lobe and thalamus. Metabolite (NAA, choline, myoinositol and Glx complex) ratios to creatine were calculated.

Results

We observed a significant negative correlation between myoinositol level in the frontal lobe and WSCT test performance. These data were confirmed by further analysis, which showed a significant correlation between WCST outcome, negative symptoms score, education level and myoinositol ratio in the frontal lobe. When analyzing negative symptoms as independent variables, the analysis of regression revealed a significant relationship between negative symptoms score and verbal fluency score, together with choline level in the thalamus.

Conclusions

The above data seem to confirm a significant role of the thalamus – a “transmission station” involved in connections with the prefrontal cortex – for psychopathology development (especially negative) in schizophrenia. Moreover, our results suggest that a neurodegenerative process may be involved in schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Keywords: schizophrenia, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, neurocognition

Background

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) is a method that allows for examination of brain function in vivo. The most replicated finding relating to schizophrenia obtained by means of 1H MRS is a lower level of NAA (N-acetylaspartate) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampal area, temporal cortex and thalamus [1]. 1H MRS in schizophrenic patients reveals, although less consistently, alterations in other brain metabolites. An increase in choline-containing compounds (Cho) was found in the caudate nucleus in first-episode drug-naive patients [2] and in the anterior cingulate, the frontal lobe and in the caudate nucleus in childhood-onset schizophrenia [3]. An increase of choline and myoinositol (mI) levels in the parietal white matter in acutely ill, medicated patients was also observed [4]. On the other hand, a decrease of choline level in the thalamus was found [5,6]. Previous 1H MRS studies in schizophrenia also reported some inconsistent results regarding Glx signal analyzed together or separately (glutamate, glutamine, GABA) [7].

Only a few studies have confirmed existence of relations between metabolite content from different brain regions and clinical symptoms of the disease. Callicott et al. observed a correlation between negative symptoms and NAA level in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex as well as in the thalamus and the anterior cingulate cortex (to a lesser extent). NAA level in the frontal cortex was lower in the group of schizophrenic patients compared to healthy controls. According to the presented hypothesis, negative symptoms should be related with lower NAA level in frontal lobes [8].

According to our previous report, after at least 7 days without neuroleptic medication, a positive symptoms score correlated positively with NAA level in the frontal lobe and negatively with NAA level in the temporal lobe [7]. Another report from our facility showed the following positive correlations: negative PANSS, general scale, total scale and choline level in the thalamus (on left side) in the group of patients in the course of neuroleptic therapy (chronic patients and first-episode patients) [9].

Choe et al. observed a positive correlation between a decrease in BPRS outcomes following the treatment and a decrease within GABA+Glu/Cr complex from the left prefrontal region [10]. Cr (creatine) level in white matter of the parietal lobe correlated positively with symptom severity in BPRS [4]. Sigmundsson et al. observed a group of patients with deficit syndrome and noticed a negative correlation between NAA level in the frontal lobe on both sides with outcomes of total PANSS scale as well as general subscale, while NAA level on the right side (but not the left) correlated negatively with outcomes of a positive subscale [11]. In the study by Galinska et al. in a group of patients after the first schizophrenia episode, negative schizophrenic symptoms correlated positively with Glx (GABA, Glu, Gln)/Cr ratio from the left temporal lobe and negatively with NAA/Cr proportion in the thalamus [12]. Fukuzako et al. studied patients with disorganized and undifferentiated schizophrenia and observed lower NAA level in the left the medial temporal lobe compared with paranoid schizophrenia patients [13]. Another study disclosed that the decrease in NAA level in the frontal lobe was higher in patients with deficit schizophrenia [14]. Tanaka et al. also observed a reverse correlation between NAA concentration in the frontal lobe and negative schizophrenic symptoms, as well as poorer WCST outcomes in chronic patients on stable doses of neuroleptics [15]. However, the majority of studies did not confirm relations between clinical symptoms and chemical compound level [13,16–20,21].

Despite presence of differences, correlations between negative symptoms and NAA level in the frontal lobe (negative) and Glx signal in the temporal lobe (positive) were observed.

Other correlations of proton spectroscopy measures examined in schizophrenia are connections with cognitive function disorders. Bertolino et al. observed a strong correlation between NAA level in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and activation of working memory, including prefrontal, temporal and lower parietal cortex [22]. Delamillieure et al. found a correlation between NAA level in the medial prefrontal cortex on the right side and outcomes of Stroop test in deficit schizophrenia patients (poorer outcomes were connected with lower NAA level) [23]. Ohrmann et al. observed relations between auditory verbal learning test outcomes and level of NAA and Glx metabolites in the frontal cortex, as well as between NAA level and executive functions in schizophrenic patients [24,25]. In studies on the first episode, Galińska et al. showed a negative correlation between NAA level in the left frontal lobe and error number in examining attention, as well as error number in WCST (executive functions) [12]. Shirayama et al. obtained similar outcomes and showed positive correlations in NAA/choline compounds proportion and negative glutamine/glutamate proportion in the medial prefrontal cortex with neuropsychological test results [26].

The aim of the present study was analysis of correlations between schizophrenia clinical symptoms, patient cognitive outcomes and brain function in 1 H MRS. We hypothesized that metabolite ratios in the frontal and temporal regions and the thalamus would significantly predict symptomatology and cognitive performance of patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Material and Methods

Course of the study

This study included patients with diagnosis of schizophrenia according to ICD-10, admitted to the Psychiatry Clinic of the Medical Academy of Bialystok and Psychiatry Hospital in Choroszcz, Poland, during the years 2003–2006. The patients were hospitalized for mental state deterioration within both positive and negative symptoms (80–120 points in PANSS). Change of treatment was scheduled for patients included in the study based on evaluation of an attending physician due to ineffectiveness of the previous treatment or development of adverse effects.

The study consisted of 2 stages. The first (prior to implemented treatment) evaluated 1H MRS outcomes, clinical symptoms and neuropsychological test results in the group of schizophrenic patients following discontinuation of neuroleptic therapy (wash-out period of 7 days minimum).

The next stage (the second study, after the treatment) took place after at least 40 days from administration of a particular neuroleptic agent in a standard dose (including at least 4 weeks of stable dose). The authors present outcomes of the first study. The studies were part of a larger program described in a different paper [27].

MRS and clinical and neuropsychological examinations were performed within 48 hours.

Examination protocol was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Medical Academy in Białystok. Every examined individual received complete data on the study and gave written consent for participation.

The studied group

The group comprised 33 men (70.2%) and 14 women (29.8%). Mean age of the patients was 32.2±5.9 years (21–45 years) (Table 1). Most of the patients were individuals with diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia (31 patients − 66%). Simple (8 patients − 17%) and undifferentiated schizophrenia (8 patients − 17%) were also diagnosed.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and neurocognitive data on the studied group.

| Studied group N=47 | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean+SD) (years) | 32.2+5.9 |

| From-to | 21–45 |

|

| |

| Education (mean+SD) (education years) | 12.3+5.9 |

| From-to | 8–17 |

|

| |

| Sex (F/M) N | 14/33 |

| % | 29.8/70.2 |

|

| |

| Duration of the disease (years) | 9.2±4.6 |

|

| |

| Number of hospitalizations | 6.9±4.3 |

|

| |

| PANSS total | 94.1±13.5 |

|

| |

| PANSS Negative | 26.0±3.4 |

|

| |

| PANSS Positive | 18.3±4.7 |

|

| |

| PANSS General | 49.5±8.4 |

|

| |

| WCST outcomes: | |

| CC | 2.9±2.4 |

| PE | 27.9±20.0 |

|

| |

| Verbal fluency score (number of words, categories+letter task) | 32.6±11.0 |

|

| |

| TMT scores | |

| TMT A (sec.) | 48.6±27.8 |

| TMT B (sec.) | 118.4±60.1 |

Mental state assessment

Mental state assessment was performed based on psychiatric examination and interview, as well as PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) [28].

Cognitive function examination

The battery of cognitive tests included:

WCST –Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. The following parameters were assessed: number of categories completed (CC) and number of perseverative errors (PE) [29].

Trail Making Test (TMT) A and B – Time of (correct) completion of both parts of the test [30].

Verbal fluency – evaluation of verbal abilities consisting of 2 parts: category fluency task and letter fluency task (number of words in both categories) [31,32].

Magnetic resonance and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

MRI and 1H MRS procedure:

MR imaging and MR spectroscopy examinations were performed at the Department of Radiology, Medical University of Bialystok, on a 1.5 T scanner (Picker Eclipse, Picker International Inc., Highlands Hts., OH, USA) using a standard circularly polarized head coil. T1-weighted FAST scans were obtained with imaging parameters of 300/4.5 ms (TR/TE), flip angle of 80°, and 5mm-thick sections. The conventional FSE T2-weighted series were acquired with parameters of 5000/127.6 ms, flip angle of 90°, and 5mm-thick sections.

1H MR spectroscopy examinations were performed with single voxel PRESS (point-resolved single voxel localized spectroscopy) sequence with higher rate sampling interval: 1 acquisition point every 256 microseconds. For these sequences, 4096 data points are acquired. The following parameters were used: TR=1500 ms, TE=35 ms (TE1~=17 ms), nex=192 and 3,906 KHz bandwidth.

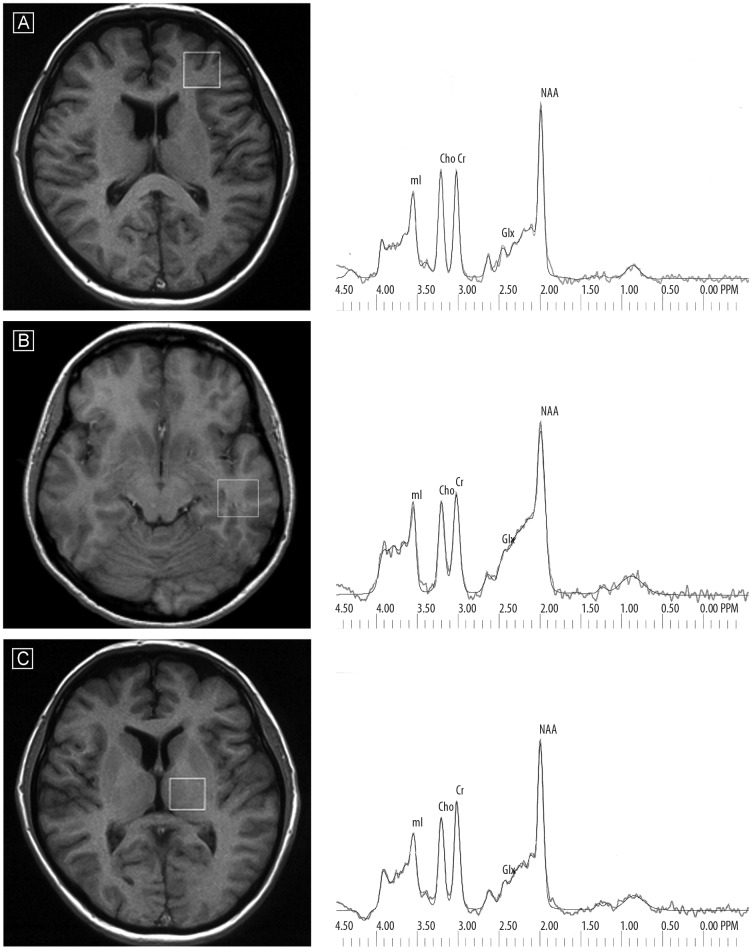

Voxels of 2×2×2 cm were positioned in the following regions of interest: in the left frontal lobe, left temporal lobe and left thalamus. To shorten scanning time, only the left-sided voxels were studied. The voxels were localized manually by a trained radiologist using T1-weighted sections: in sagittal, coronal and axial planes, reducing the inclusion of CSF. The left frontal lobe voxel was located above the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles and encompassed mainly frontal white matter (forceps minor) and the cortex of the superior and medial frontal gyrus. The left temporal lobe voxel was placed in the infero-lateral region of the temporal lobe, including white matter and cortex of the medial and inferior temporal gyrus. The left thalamus voxel was placed on the slice, where the thalamus (the dorsal-medial nucleus) is the most prominent and covered all thalamic nuclei and small portions of other structures such as the posterior limb of the internal capsule (Figure 1). The signal over the voxel of interest was shimmed to within a line-width of 3 to 7 Hz and transmitter pulse power was optimized by automated procedures. The lineshape deconvolution (Eddy current correction [ECC]) was used. MOIST (Multiply Optimized Insensitive Suppression Train) method was used for suppressing the signal from water. MOIST sequence is a modification of CHESS sequence with a conjugate gradient minimalization technique to optimize tip angles and pulse shape.

Figure 1.

Voxel placement in three regions of interest and exemplary spectra (of schizophrenic patients) with raw and fitted data for each region – the frontal lobe (A), temporal lobe (B) and thalamus (C).

Following data acquisition, post-processing was performed with software provided by the manufacturer (Via 2.0 by Picker) by 2 neuroradiologists in consensus (blind to group and time of rescan). The 1H MRS data were zero-filled to 8192 points and residual water resonances were removed using time-domain high-pass filtering. Exponential to Gaussian transformation was applied as a time-domain apodizing Gaussian filter F(t)=exp[− (At+(Bt)^2)] (A=0 Hz, B=1.5 Hz). Next, data were Fourier transformed and phase corrected. After application of a Legendre polynomial function to approximate the baseline, an automated curve fitting was performed using an iterative, nonlinear-least-squares fitting procedure by means of Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Line-shapes of the simulated peaks used in the fitting process were fixed with 85% Gaussian and 15% Lorentzian fractions. Only spectra with the best fit (ie, spectra with exactly overlapping and adjusted raw spectrum lines [with flat residual spectral line]) were included. Then metabolites to creatine and unsuppressed water ratios were analyzed. The following metabolites were assessed: NAA at 2.01 ppm, Glx (GABA, glutamine, glutamate) in the area from 2.11 ppm to 2.45 ppm, Cho (choline-containing compounds) at 3.22 ppm, Cr (creatine plus phosphocreatine) at 3.03 ppm, mI at 3.56 ppm (Figure 1) [33].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by means of STATISTICA 9.0 software by Statsoft Poland. All the data was tested on normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test). Next, parametric or non-parametric tests were applied, depending on the outcomes.

In order to examine correlations and relations between 1H MRS outcomes and demographic, clinical and neuropsychological data, Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Spearman’s rank coefficient were counted and multiple regression models were applied (stepwise forward). The significance level was considered as 0.05.

The data are presented as mean ±SD.

Results

Patients were assessed after the wash-out period without neuroleptic treatment, to eliminate the influence of antipsychotics on examined measures. The mean wash-out period was 9.4±3.2 days.

The clinical and neurocognitive outcomes are presented in Table 1. Table 2 shows 1H MRS measures in the studied group.

Table 2.

Average ratios of metabolites in schizophrenic patients.

| Patients mean±SD | |

|---|---|

| Metabolite ratios/the frontal lobe | N=45 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.72±0.26 |

| Cho/Cr | 0.97±0.21 |

| mI/Cr | 0.70±0.15 |

| Glx/Cr | 2.15±0.42 |

| Metabolite ratios/the thalamus | N=46 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.79±0.18 |

| Cho/Cr | 0.86±0.09 |

| mI/Cr | 0.56±0.10 |

| Glx/Cr | 1.84±0.27 |

| Metabolite ratios/the temporal lobe | N=43 |

| NAA/Cr | 1.72±0.29 |

| Cho/Cr | 0.98±0.17 |

| mI/Cr | 0.71±0.13 |

| Glx/Cr | 2.25±0.40 |

Correlations of 1H MRS measures

We predicted that some data (clinical symptoms and cognitive measures) would be correlated, so we decided to perform 2 analyses assessing the clinical symptoms and cognitive outcomes as independent variables separately, to examine the most significant connections with 1H MRS measures.

Clinical symptoms as independent variables

The analysis included correlations between negative, positive and general PANSS and 1H MRS outcomes. Additionally, relations of clinical symptoms with demographic data were analyzed with neuropsychological outcomes for the purpose of obtaining a more complete view of the described relations.

The following significant correlations were obtained in the study:

PANSS-Negative score: Cho/Cr in the frontal lobe, r=−0.33; p=0.030; Cho/Cr in the thalamus, r=−0.47; p=0.001; TMT part A, R =0.53; p=0.0005; Verbal fluency score r=−0.56; p=0.0002; CC, R=−0.35; p=0.017.

PANSS-Positive score: − no statistically significant correlations observed.

PANSS – General score: Cho/Cr in the thalamus, r=−0.31; p=0.038; TMT A, R=0.44; p=0.003.

For a more precise evaluation of relations between clinical symptoms and 1H MRS outcomes and other data, a method of multiple regression (stepwise forward) was applied.

The analysis included influence of chemical compounds on results of clinical scales separately and totally with other data that were considered most strictly connected with schizophrenia symptom severity, including neuropsychological test results.

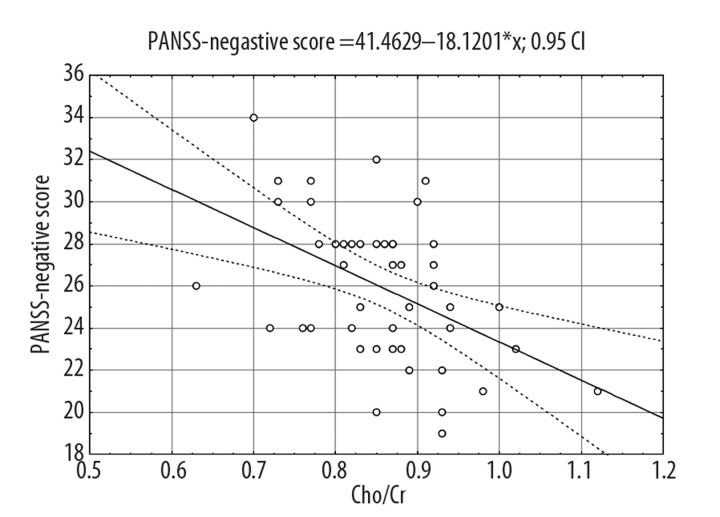

The tables below present the following information: independent variables that were included into the regression model, measurement of matching the model to empirical data, evaluation values of standardized regression coefficients and evaluation of statistical significance. The following models, which explain independent variables variance most accurately, were obtained. As regards the equation representing outcomes of regression for PANSS – Negative score, Cho/Cr proportion in the thalamus was the only neurochemical variable that significantly explained the independent variable (20% variance) (Figure 2). Verbal fluency together with Cho/Cr explained 50% of the variance in PANSS – Negative score. In this model the verbal fluency variable showed significant influence on the clinical variable; CC and TMT A variables were not included into the model (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Analysis of correlation between PANSS-Negative score and Cho/Cr in the thalamus.

Table 3.

Regression analysis outcomes for PANSS – Negative score variable.

| PANSS-Negative score | Variance% | F | df | p | Standardized β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalamic Cho/Cr | 20 | 12.24 | 1, 44 | 0.001 | −0.47 |

|

| |||||

| Thalamic Cho/Cr | 50 | 21.76 | 2, 40 | <0.001 | −0.42 |

| Verbal fluency score | −0.53 | ||||

The described equation illustrated a considerably strong dependency between negative aspects of schizophrenia and choline level in the thalamus as well as language functions. Neurochemical proportions introduced to the model, which explains PANSS-General score, revealed no significant influence in the regression model.

Executive functions as independent variables

We chose WCST outcomes as the most significant cognitive measures and constructed the analysis of regression with clinical symptoms and 1H measures.

The following significant correlations of WCST outcomes were observed:

Number of categories completed (CC) − mI/Cr in the frontal lobe, R=−0.38; p=0.010; education, R=−0.36, p=0.019; PANSS Negative score, R=−0.35; p=0.017.

Number of perseverative errors (PE): education, R=−0.41; p=0.006.

Moreover, a regression model was built for a variable: number of categories completed (CC). The regression model for PE did not reveal any significant correlations.

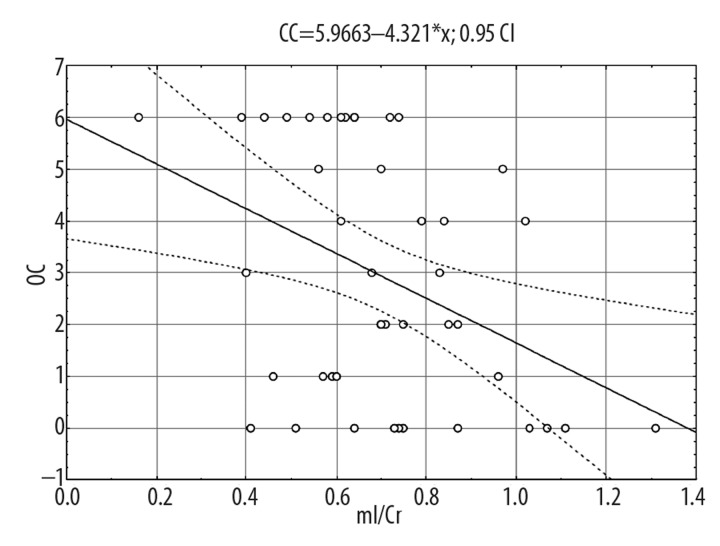

Outcomes on CC variable are presented in Table 4. The following model explained the independent variable variance most accurately. Proportion of mI/Cr in the frontal lobe explained 16% of the variance in CC scores (Figure 3) and, together with education and negative symptoms score, explained 38% of the variance in CC score.

Table 4.

Regression analysis outcomes for number of categories completed (CC) score.

| CC | Variance% | F | Df | p | Standardized β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal mI/Cr | 16 | 9.30 | 1, 41 | 0.004 | −0.43 |

| Frontal mI/Cr | 38 | 9.90 | 3, 40 | <0.001 | −0.37 |

| Education | 0.32 | ||||

| PANSS Negative score | 0.32 |

Figure 3.

Analysis of correlation between the number of categories completed (CC) in WCST and mI/Cr in the frontal lobe.

To conclude, a significant influence of mI/Cr proportion in the frontal lobe on WCST outcomes was observed – the lower the proportion, the better the outcomes. CC variable was also strongly influenced by the level of education and negative symptom severity.

Discussion

Clinical symptoms of schizophrenia, mainly negative, were considerably strongly related (negatively) to Cho/Cr proportion in the thalamus; this proportion separately explained 20% of the variance in PANSS-Negative score, and together with verbal fluency variable they explained 50% of the variance in PANSS-Negative score. This may suggest existence of dependencies between choline level in the thalamus and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Also, a considerably strong relation between negative symptoms and verbal fluency was observed – stronger severity of symptoms was accompanied by worse outcomes obtained by patients in verbal fluency test. Similarly, analysis of regression revealed a negative relationship between WCST measure (CC) and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The relation between negative symptoms and cognitive deficit in schizophrenia is emphasized in the literature [34].

The previous study in our facility involved a group of patients with first schizophrenia episode and chronic form of the disease and showed a correlation between clinical symptoms in PANSS, including negative symptoms, and Cho/Cr proportion in the thalamus, yet it was a positive correlation. The studied group comprised 47 patients, mainly individuals with the first episode (30 persons) [9]. We performed another analysis of the database of the described study and positive correlations were observed only in first-episode patients. Apart from this, the previous work showed that choline level in the frontal lobe in chronic schizophrenia patients was higher compared with the control group. Also, a tendency towards increased choline level in the temporal lobe was observed compared with the first-episode group. Moreover, a slight increase in choline level in the thalamus was observed in both groups compared with the control group [9]. Ohrmann et al. found a decrease in prefrontal choline level in chronic schizophrenia compared to first-episode patients and healthy controls [24]. An increase of choline concentration was reported mostly among first-episode patients; data on chronic patients are less consistent [2,3]. Also, a positive relation between period of untreated psychosis and choline level in the left cingulate gyrus and in the thalamus was found in first-episode patients [35]. Moreover, choline concentration may vary depending on brain region and/or white and grey matter, which may confound the comparison of different studies [36].

This confirms the hypothesis that increased choline level occurs in different parts of the brain in pre-disease period and is observed more frequently in first-episode patients or very early disease onset, and then it is reduced with disease duration and course. The influence of the neuroleptic treatment may be the reason for some discrepancies seen in previous papers, yet in our study we analyzed patients after the neuroleptic wash-out (to eliminate the treatment effect). Analysis of our results leads to a conclusion that choline level in the thalamus is related to schizophrenia symptoms, especially negative ones. Moreover, it can be assumed that changes in choline content in proton MR spectroscopy reflect disorders in membranous phospholipid movement. A decrease in choline level is suggested to be related to a reduction in the amount of cell membrane per unit volume in a given brain region. In the literature a relation between membranous phospholipid disorders and schizophrenia negative symptoms was also observed [4,36,37]. However, it should be emphasized that the role of choline signals in 1H MRS is still unclear and further studies are needed to explain its significance in schizophrenia pathogenesis [38].

During analysis of mutual relations of neuropsychological test outcomes, 1H MRS outcomes, clinical symptoms and other data, a significant relation between myoinositol level in the frontal lobe and WCST outcomes was observed – the higher the myoinositol level, the more perseverative errors patients made (regardless of education) and they completed fewer categories. The number of completed categories was significantly influenced also by education level and negative symptom severity. This suggests that patients with more severe negative symptoms and lower education (which are connected with each other) had poorer WCST outcomes. To date, the main correlation observed has been between NAA level in the frontal lobe and neuropsychological test results within working memory and executive functions [12,22,23,25,39]. The present study showed no significant relations between NAA/Cr proportion in the examined brain regions in schizophrenic patients and clinical symptoms and neuropsychological test results.

An increased myoinositol level and a decreased NAA level in the temporal, parietal and occipital regions have been observed in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Reverse correlation between myoinositol level in parietal, parietal-occipital and frontal regions and Mini Mental State test was observed, while a positive correlations between MMS examination outcome and NAA level were also found [40–42]. A reverse correlation was observed between mI/H2O proportion in the temporoparietal cortex and language function and visual-constructive skill, as well as between mI/H2O proportion in the frontal cortex and executive functions (TMT), yet this correlation appeared insignificant after Bonferroni correction [43]. According to another study, mI/NAA proportion in the parietal region (cortex and white matter) showed a reverse correlation with MMSE outcomes and other results of CERAD test series (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease), including verbal fluency [44]. A correlation between myoinositol level in the frontal lobes and cognitive disorders (including executive functions) was also observed in AIDS dementia. In this disorder it was also observed that changes in mI (increased) and NAA (decreased) normalized with symptom improvement following successful therapy [45,46].

The presented results prove the existence of relations between myoinositol level in the examined brain portions and executive functions in chronic schizophrenia patients. Those correlations were observed mainly in cases of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, while in the cases of first schizophrenia episode and in healthy individuals a different correlation pattern was observed – most frequently, positive correlations with frontal NAA level [12,24,47,48]. The data may confirm the existence of neurodegenerative processes in chronic schizophrenia.

Our study has several limitations, mostly due to the technical aspects of MRS methods. First, we analyzed metabolite/Cr ratios, not absolute concentrations. However, most studies also used ratios and Cr level is considered relatively stable by some authors [40]. On the other hand, some studies in schizophrenia reported changes in Cr signal. Amongst them, Ohrmann et al. found a decreased Cr concentration in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia patients [24]. Hence, the statement about the stability of Cr level in schizophrenic patients should be interpreted with caution. In addition, we did not perform any tissue segmentation within the volume of interest to eliminate combining white and grey matter. This procedure was not available in our study, so we cannot rule out the possibility of regional variations in metabolite concentration. The voxels from our study in the frontal and temporal lobes included white matter. Moreover, the radiologist who positioned the voxels made every effort to include as much grey matter as possible and to avoid an inclusion of CSF. All the voxels were reflecting the same regions and localized in the same place in all the subjects (patients before and after treatment and controls).

We did not present the comparison of our group of schizophrenic patients and controls. These data were described in our other paper (the current study was part of a larger project). We found a significant decrease of NAA/Cr ratio in the frontal lobe and thalamus in the group of patients, which is consistent with most other studies [27]. However, we did not observe any differences in choline and myoinositol levels between patients and controls.

Conclusions

Executive functions in chronic schizophrenic patients correlated inversely with frontal myoinositol level, which is supposed to be the marker of neurodegeneration. Negative symptoms correlated inversely with thalamic choline level, which may reflect the disorders in membranous phospholipid turnover in this structure. Study outcomes seem to confirm a significant role of the thalamus – a “transmission station” involved in connections with the prefrontal cortex – for psychopathology development (especially negative) in schizophrenia [49–51]. Moreover, the above data suggest that a neurodegenerative process may be involved in schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Brugger S, Davis JM, Leucht S, Stone JM. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Illness Stage in Schizophrenia – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustillo JR, Rowland LM, Lauriello J, et al. High Choline Concentrations in the Caudate Nucleus in Antipsychotic-Naïve Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:130–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill J, Levitt J, Caplan R, et al. 1H MRSI evidence of metabolic abnormalities in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1781–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auer DP, Wilke M, Grabner A, et al. Reduced NAA in the thalamus and altered membrane and glial metabolism in schizophrenic patients detected by 1H MRS and tissue segmentation. Schizophr Res. 2001;52:87–99. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omori M, Murata T, Kiura H, et al. Thalamic abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia revealed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2000;98:155–62. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ende G, Braus DF, Walter S, Henn F. Lower Concentration of Thalamic N-Acetylaspartate in Patients With schizophrenia: A Replication Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1314–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szulc A, Galińska B, Tarasów E, et al. The Effect Of Risperidone on Metabolite Measures In the Frontal Lobe, Temporal Lobe, and The thalamus In Schizophrenic Patients. A Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H MRS) Study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38:214–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callicott JH, Bertolino A, Egan MF, et al. Selective Relationship Between Prefrontal N-Acetylaspartate Measures and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1646–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szulc A, Galinska B, Tarasow E, et al. Clinical and neuropsychological correlates of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy detected metabolites in brains of first episode and chronic schizophrenic patients. Psychiatr Pol. 2003;37:977–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choe B, Suh TS, Shin KS, et al. Observation of Metabolic Changes in Chronic Schizophrenia After Neuroleptic Treatment by In Vivo Hydrogen Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Investigative Radiology. 1996;31:345–52. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigmundsson T, Maier M, Toone BK, et al. Frontal lobe N-acetylaspartate correlates with psychopathology in schizophrenia: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galinska B, Szulc A, Tarasow E, et al. Relationship between frontal N-acetylaspartate and cognitive deficit in first-episode schizophrenia. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13(Suppl 1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuzako H, Kodama S, Fukuzako T, et al. Subtype-associated metabolite differences in the temporal lobe in schizophrenia detected by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 1999;92:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delamillieure P, Fernandez J, Constans JM, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the medial prefrontal cortex in patients with deficit schizophrenia: preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:641–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka Y, Obata T, Sassa T, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance spectroscopy of schizophrenia: Relationship between decreased N-acetylaspartate and frontal lobe dysfunction. Psych Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:365–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartha R, Williamson PC, Drost DJ, et al. Measurement of Glutamate and Glutamine in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex of Never-Treated Schizophrenic Patients and Healthy Controls by Proton Resonance Spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:959–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220085012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartha R, Al-Semaan YM, Williamson PC, et al. A short echo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the left mesial-temporal lobe in first-onset schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1403–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertolino A, Callicott JH, Mattay VS, et al. The Effect of Treatment with Antipsychotic Drugs on Brain N-Acetylaspartate Measures in Patients with Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00997-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Rowland LM, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of neurochemical changes during the first year of antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia patients with minimal previous medication exposure. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:313–21. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fannon D, Simmons A, Tennakoon L, et al. Selective Deficit of Hippocampal N-Acetylaspartate in Antipsychotic-Naïve Patients with Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:587–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuzako H. Heritability heightens brain metabolite differences in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:95–97. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertolino A, Esposito G, Callicott Jh, et al. Specific Relationship Between Prefrontal Neuronal N-Acetylaspartate and Activation of the Working Memory Cortical Network in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:26–33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delamillieure P, Constans JM, Fernandez J, et al. Relationship between performance on the Stroop test and N-acetylaspartate in the medial prefrontal cortex in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia: preliminary results. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2004;132:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohrmann P, Siegmund S, Suslow T, et al. Cognitive impairment and in vivo metabolites in first-episode neuroleptic-naive and chronic medicated schizophrenic patients: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:625–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohrmann P, Kugel H, Bauer J, et al. Learning potential on the WCST in schizophrenia is related to the neuronal integrity of the anterior cingulate cortex as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:156–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirayama Y, Obata T, Matsuzawa D, et al. Specific metabolites in the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia: A preliminary study. NeuroImage. 2010;49:2783–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szulc A, Galinska B, Tarasow E, et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of brain metabolite changes after antipsychotic treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44:148–57. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Computer Version 3 For Windows. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1990, 1993, 1999. Research Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reitan RM. The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Cons Psychol. 1958;19:393–94. doi: 10.1037/h0044509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucki W. Tests for evaluation of cognitive deficits in patients with organic brain damage. Warsaw: PTP PTP; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talarowska M, Florkowski A, Zboralski K, Galecki P. Cognitive functions impairment depending on clinical traits of unipolar recurrent depression – preliminary results. Psychiatria i Psychoterapia. 2010;6(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarasow E, Kubas B, Walecki J. MR proton spectroscopy in patients with CNS involvement In Bourneville’s disease. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:762–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borkowska A, Wiłkosc M, Tomaszewska M, Rybakowski J. Working memory: neurobiological and neuropsychological issues. Psychiatr Pol. 2006;40:383–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theberge J, Al-Semaan Y, Drost DJ, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis vs. N-acetylaspartate and choline in first episode schizophrenia: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 4.0 Tesla. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2004;131:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bracken BK, Jensen JE, Prescot AP, et al. Brain metabolite concentrations across cortical regions in healthy adults. Brain Res. 2011;1369:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horrobin DF, Glen AIM, Vaddadi A. The membrane hypothesis of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1994;13:195–207. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross BD, Coletti P, Lin A. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of The Brain: Neurospectroscopy. In: Edelman RR, Hesselink JR, Zlatkin MB, Cruess JV III, editors. Clinical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1840–907. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertolino A, Ciota D, Brudaglio F, et al. Working Memory Deficits and Levels of N-Acetylaspartate In patients With Schizophreniform Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:483–89. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross AJ, Sachdev PS. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cognitive research. Brain Res Rev. 2004;44:83–102. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldman AD, Rai GS. The relationship between cognitive impairment and in vivo metabolite ratios in patients with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:507–12. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-1040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rose SE, Zubicaray GI, Wang D, et al. A 1H MRS study of probable Alzheimer’s Disease and normal aging: implications for longitudinal monitoring of dementia progression. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:291–96. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(98)00168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chantal S, Labelle M, Bouchard RW, et al. Correlation of Regional Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Metabolic Changes With Cognitive Deficits in Mild Alzheimer Disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:955–62. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackl N, Ising M, Screiber YA, et al. Hippocampal metabolic abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang L, Ernst T, Witt MD, et al. Relationship among Brain Metabolites, Cognitive Function, and Viral Loads in Antiretroviral-Naïve HIV Patients. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1638–48. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ernst T, Chang L, Arnold S. Increased glial metabolites predict increased working memory network activation in HIV brain injury. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1686–93. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jung RE, Haier RJ, Yeo RA. Sex differences in N-acetylaspartate correlates of general intelligence: An 1H MRS study of normal human brain. Neuroimage. 2005;26:965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfleiderer B, Ohrmann P, Suslow T, et al. N-acetylaspartate levels of left frontal cortex are associated with verbal intelligence in women but not in men: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuroscience. 2004;123:1053–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS. „Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfuncion in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:203–18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris R, Kumari V. The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:117–45. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]