Summary

Background

The impact of bleaching on the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) is not well known. Due to frequent sensitivity of the cervical region of teeth after the vital bleaching, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the morphological features of the CEJ of human teeth after application of fluoridated and fluoride-free bleaching agents, as well as post-bleaching fluoridation treatment, by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis.

Material/Methods

Thirty-five extracted permanent human teeth were longitudinally cut, yielding 70 specimens. Thirty specimens were randomly divided into the 3 experimental groups, and 20 specimens, were used as (2) control groups, each: negative (untreated) control group; positive control group treated with 35% hydrogen peroxide; experimental group 1, bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide (CP); experimental group 2, treatment with a mixture of 10% CP and fluoride; and experimental group 3, treatment with 10% CP and 2% sodium fluoride gel applied 30 minutes after bleaching. Experimental groups were treated 8 h per day for 14 days. The samples were examined by SEM.

Results

The bleaching materials tested caused morphological changes to the surface of the CEJ. There was a statistically significant difference between experimental groups (Kruskal Wallis Test chi-square=11,668; p<0.005). Mean value of experimental group 2 scores showed statistically significant difference from groups 1 and 3.

Conclusions

Bleaching gel with fluorides does not significantly change morphological appearance of the CEJ and represents a better choice than the hard tissue fluoridation process after bleaching.

Keywords: cemento-enamel junction, bleaching, carbamide peroxide, fluoride, scanning electron microscopy

Background

The cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) of permanent teeth is of increased clinical significance owing to its association with CEJ dentin sensitivity and susceptibility to pathological changes. These changes include root surface caries, cervical erosion, resorption and abrasion.

In young permanent teeth, the CEJ is protected by gingival tissues [1]. Wearing off of the incisal and occlusal surface was compensated by continuous passive eruption. Finally, the CEJ is exposed to the oral environment, and, in these conditions, it is subjected to various chemical and physical agents that may alter its morphology [1]. Some of these changes may occur after tooth bleaching treatment. Namely, vital bleaching could lead to cervical sensitivity, whereas after non-vital bleaching, external cervical resorption takes place [1].

Little is known about the impact of bleaching on the CEJ. Many studies have investigated the effects of bleaching on structural, chemical and mechanical enamel characteristics [2–4]. Some of these are related to dentin [5,6], as well as to cementum [7,8]. Apart from a comprehensive study by Esberard et al. [9], where evidence was presented of ultrastructural changes after the effect of the agents for internal and external bleaching, there are almost no other data.

To prevent either reduction in micro-hardness or demineralization accompanying tooth-whitening therapy, some manufacturers have incorporated fluorides into their bleaching gel formulas [10–13]. However, there is insufficient scientific data regarding the morphological changes in enamel after the application of fluorinated bleaching agents, as well as the impact of fluoride on the morphology of already bleached enamel, especially on a specific region such as the CEJ. Due to possible sensitivity in the cervical region of the tooth which may be reduced by fluoride application after vital bleaching treatment, the aim of this paper was to explore the difference in morphological changes in the cemento-enamel junction after the use of fluoride-free and fluoridated bleaching agents, as well as post-bleaching fluoridation treatment. The hypothesis was that the bleaching agents without fluoride ingredients would alter the CEJ morphology.

Material and Methods

This study was developed after approval by Local Ethics Committee (No. 01-7289-7/2011). Forty freshly extracted permanent human teeth were used for this study. The teeth were cleaned taking special care to avoid any damage to the cervical region. After removal of organic and inorganic materials from the tooth surface (ultrasound JUS-S01, JEOL, with distilled water and neutral shampoo), the integrity of the CEJ was analyzed using a stereomicroscope (SMXX, Carl Zeiss-Jena, Germany). Five teeth with defects in this region were not subjected to further analysis, but 35 teeth planned for subsequent protocol were stored in distilled water at room temperature until use.

The teeth were cut into halves, parallel to the long axis in a mesio-distal plane using a diamond turbine drill (with water cooling). Medial and apical parts of the root were also removed in order to reduce the specimen size and ensure easier adaptation to metal supports for SEM analysis; 70 samples were obtained in this way. Out of 70 samples, 40 were used as 2 control groups (equally). Thirty specimens were randomly divided into 3 experimental groups. Table 1 lists the bleaching agents’ characteristics, manner of application, duration of contact and number of specimens for each group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of bleaching agents, application, bleaching time and number of specimens for each group.

| Group | Product | Manufacturer | Active ingrediens | pH | Application | Storage medium | Bleaching time | No. of spec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | Distilled water | 20 | ||||||

| Positive control | Hydrogen peroxide | Tehnochem, Belgrade, Serbia | 35% HP | 5.5 | 35% HP only | Distilled water | 1:03 hrs | 20 |

| Experimental group 1 | Nite White ACP | Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA | 10% CP, Amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP), potassium nitrate, fluoride in trace (3.82 ppm)11 | 6.011 | 10% CP only | Filtrated human saliva | 112 hrs | 10 |

| Experimental group 2 | Nite White ACP | Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA | 10% CP, ACP, potassium nitrate, fluoride in trace (3.82 ppm) | 6.0 | 10% CP+F as a mixture | Filtrated human saliva | 112 hrs | 10 |

| Relief ACP | Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA | 2% Sodium fluoride, potassium nitrate, ACP | 6.4 | |||||

| Experimental group 3 | Nite White ACP | Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA | 10% CP, ACP, potassium nitrate, fluoride in trace (3.82 ppm) | 6.0 | 10% CP with F for 30 min. after each bleaching treatment | Filtrated human saliva | 112 hrs | 10 |

| Relief ACP | Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA | 2% Sodium fluoride, potassium nitrate, ACP | 6.4 |

Control groups

Negative control group

The negative control group included teeth not treated with any bleaching agents in order to establish relationship of mineralized tissue that makes up the CEJ, as well as morphological characteristics of enamel and dentin, separately. All negative control specimens were stored in distilled water until they were prepared for SEM analysis.

Positive control group

The positive control group included specimens treated with 35% hydrogen peroxide (HP) (Techohem Beograd, Serbia) without fluoride and without placing in human saliva, in order to get the strongest possible effect on the CEJ morphology.

These specimens were treated according to the methodology described by Esberard et al. [9] It included 3 sessions of bleaching gel (35% hydrogen peroxide, pH 5.5) for 21 minutes each. Every session included 3 bleaching applications, 7 minutes each, which were started and finished by 2-minute gel activation by means of visible light (Ledition, Ivoclar Vivadent)). After the bleaching procedure, the specimens were rinsed with running water. The other 2 sessions were performed after 48 and 96 hours. Between the series, the specimens were kept in distilled water until their preparation for SEM. Total exposure time of the bleaching material was 63 minutes.

Saliva collection and preparation

Fresh human saliva was collected from healthy volunteers in the morning after 2 h of fasting. Subjects were told to rinse twice with distilled water before saliva collection [14]. Filtrates were obtained with Whatman filter papers grade 1:11 μm (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). One-day-old saliva was always used.

Experimental group 1

The specimens in this group were exposed to home bleaching treatment with 10% carbamide peroxide (CP) (pH about 6.02) [15] (Nite White ACP Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA). The bleaching gel was applied in a quantity sufficient to cover the CEJ. According to the methodology of Esberard et al. [9] (described earlier) the CEJ was exposed to bleaching agent for 8 hours a day. Between the bleaching gel applications, the specimens were kept in filtrated human saliva. For the entire period of this experimental protocol, including gel applications and storing in saliva, the specimens were placed in an incubator at 37°C and 100% humidity. Immediately after the application of bleaching gel, the specimens were rinsed with running water. Total exposure time to the bleaching material was 112 hours.

Experimental group 2

The CEJ specimens were treated with a mixture of 10% CP and 2% fluoride gel (Relief ACP, Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA). The procedure and duration of bleaching was identical to that of the Experimental group 1, the difference being in adding fluoride gel to the bleaching agent. With a special indicator paper (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, with scale 5.4–7.0) it was found that fluoride gel pH was 6.4.

Experimental group 3

Specimens were treated as in Experimental group 1 (10% CP) but with additional topical fluoridation using 2% sodium fluoride gel Relief ACP (Discus Dental, Inc. Culver City, USA) for 30 minutes after each bleaching treatment.

Specimens’ preparation for SEM

After allowing the specimens to air-dry, they were fixed to aluminium stubs with a fixing agent (Dotite paint xc 12 Carbon JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), sputter-coated with gold/palladium ((in the unit JFC 1100E Ion Sputter JEOL), and examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JEOL-JSM-5300). Three experienced examiners (oral pathologists) scored each image independently, which were coded and randomly mixed so that the examiners did not know the area from which a given sample originated. When the examiners independently agreed on a score, it was recorded. When disagreement occurred, they discussed the sample and its scoring, and agreement on a score was reached.

The morphological changes were assessed only in experimental groups of specimens.

Assessment was made as follows [9]:

Score 0 – no changes observed on the bleached specimens.

Score 1 – slightly altered appearance compared to negative control specimens.

Score 2 – a small depression between enamel and cementum.

Score 3 – specimens demonstrating considerable change at the CEJ, namely, a significant depression between enamel and cementum with large separation between both tissues, similar to changes in the positive control group.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the nonparametric chi-square test and Kruskal-Wallis test (SPSS 10.0 statistical software; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA); a p-value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Negative control group

This group of specimens did not have the bleaching treatment and they were stored in human saliva. Interrelation of the mineralized tissue composing the CEJ was as follows: 12 of 20 specimens showed the enamel is overlapped by cementum, 5 showed existence of edge-to-edge relationship and 3 specimens had a gap between the enamel and cementum, but dental tubules were not exposed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Negative control group. (A) SEM appearance of the CEJ shows the most frequent type: cementum goes over the enamel surface. (B) “Wave-like” appearance of the CEJ. A gap between enamel and cementum can be observed, of approximate 10 μm in size, partially filled with fragments of inorganic contents. In the upper gap part a structure is observed, which according to its morphological appearance, does not correspond either to the enamel or the cementum, but even with higher magnification, there were not observed dental tubules to confirm that it was dentin.

Positive control group

These specimens were treated with 35% H2O2, without fluoride treatment and without storing them in human saliva. A significant difference was observed in the enamel and cementum morphology compared to negative control specimens and experimental groups. Except for the strong cementum depression and its conspicuously lower level in relation to enamel, there was observed CEJ splitting and enamel separation from cementum. Enamel morphology by the junction was changed; the enamel margin was uneven, there were extensive flattening and porosity of the surface, and erosive, type II changes. There was a significant cementum loss and dentin with open tubules. Other cementum part showed significant irregularity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Positive control group-specimens treated with 35% HP. (A) Notable splitting of enamel from cementum tissue and cementum is involved under the enamel. The enamel edge is ragged at some points and the morphological appearance of enamel surface indicates erosive Type II changes. (B) Very close to the CEJ there may be observed open dentinal tubules. The strip of dentin indicates the possible removing of the intermediate cementum by means of bleaching agent. Other cementum part shows conspicuous irregularity.

Experimental group 1

This group of specimens was treated with 10% carbamide peroxide without fluoride addition. The majority of specimens showed a difference in enamel and cementum levels, with occurence of pit-like appearance of the cementum structure. Cementum cavities were very expressed in certain points. In the majority of the specimens there was a recess on the CEJ, and on most interfaces there were significant cementum irregularities and notable enamel prisms (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Experimental group 1 (Bleaching with 10% fluoride-free carbamide peroxide). (A) Minor lesion of cervical hard dental tissues of lower premolar mesial side. The CEJ is below both the cementum and enamel levels. Enamel surface immediately by the junction indicates “stripping” of prisms parts positioned vertically. There are expressed enamel “caps” along the enamel edge. (B) The CEJ indicates cracks on the enamel margin with insignificantly changed enamel surface and more expressed cement changes which has a pitted appearance with pits of different depths. There may be observed a significant depression of the cementum.

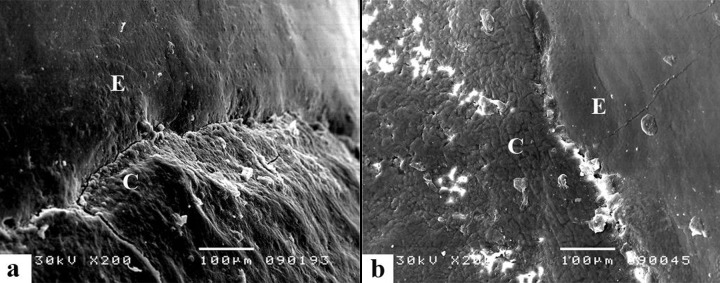

Experimental group 2

This group was composed of specimens treated with 10% fluoride-added carbamide peroxide. Several specimens showed that the cement layer was lower compared to that of the enamel. No changes were observed in the morphology of mineralized tissues that compose the CEJ. On most interfaces of specimens there was gradual transition of cementum into the enamel, without damage to intermediate cementum and exposing dentin structure (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Experimental group 2 (Bleaching with 10% fluoride-added carbamide peroxide). (A) There is a minor depression of the cementum tissue which preserved its morphology. The enamel margin is rounded and CEJ is shown as an edge to edge model. (B) Higher magnification confirms that there is good relationship between marginal structures composing the CEJ. Morphological appearance of the cementum is insignificantly changed.

Experimental group 3

In experimental group 3 fluoride was applied after the bleaching treatment. The CEJ and tissues along the junction were masked by structures resembling CaF2. Morphology of junction was not disturbed, although some specimens showed significant irregularity of the cementum surface (Figure 5.)

Figure 5.

Experimental group 3 (Bleaching with 10% carbamide peroxide and fluoride application after teeth bleaching). (A) CEJ morphological appearance looks as if masked with structures resembling the fluoride compounds. The junction between the enamel and the cementum is not clearly observable but it is on the same level. Part of cementum has got a pitted appearance. (B) In higher magnification there may be observed cementum irregularity but also the structures which are not the constituent part of the cementum morphology.

Table 2 presents the scores of morphological changes in the tissue that composes the CEJ in the experimental groups of specimens. A score of 0 was assigned to 2 specimens from experimental group 2, and a score of 3 was assigned to 2 specimens from group 3.

Table 2.

Scores of morphological changes on the CEJ and statistical data of significance among the experimental groups.

| Exp. group | N spec. | Sc. 0 | Sc. 1 | Sc. 2 | Sc. 3 | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max | Kruskal Wallis Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2.00 | 0.67 | 1 | 3 | Chi-quare=11.668 |

| 2 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0.90 | 0.57 | 0 | 2 | p=0.003 |

| 3 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1.60 | 0.52 | 1 | 2 | p<0.005 |

By testing the mean values of scores, it was demonstrated that there was a statistically significant difference in the mean values between experimental groups (Kruskal Wallis Test Chi-Square=11,668; p<0.005)

Mean value of experimental group 2 scores showed statistically significant difference from groups 1 and 3. The Kruskal Wallis test did not demonstrate statistically significant difference between experimental groups 1 and 3.

Discussion

Morphological changes in the CEJ region are harder to detect than the changes occurring separately on hard dental tissues, enamel or cementum. According to methodology proposed by Esberard et al [9], in order to avoid wrong interpretation of the CEJ morphological changes, a large number of specimens are necessary for control. In this study, both positive and negative control groups contained twice the number of specimens than each of the experimental groups.

In order to get the most realistic insight into the ultrastructural changes on the CEJ and the maximum possible lesions of cementum and enamel structures after bleaching, one group of teeth was exposed to high concentration (35%) of hydrogen peroxide, imitating in-office bleaching. These specimens were not treated with fluoride and were not immersed in filtrated human saliva, which resulted in omission of the potential remineralizing factor of the environment which would have existed in case of in vivo conditions. This group of specimens was designated as a positive control group, and morphological changes established in this group of specimens represented a parameter for the highest score value.

Human saliva as storage media may contribute to the protection of the enamel (and cementum) surfaces through its remineralization effect between the treatment episodes. Earlier studies also showed that the effects of whitening treatment on surface enamel were less severe when human saliva was used as storage media [16].

According to Attin et al. [3], although artificial saliva can re-harden the surface of the softened enamel, human saliva seems to be better because it imitates the natural conditions much better. The use of fluoride as usual in everyday situations and the use of human saliva are important for estimating the impact of bleaching agents on dental enamel under clinical conditions in the oral cavity [3]. It may be assumed that similar changes occur in cementum as well.

In our research, filtered human saliva was used, although some studies recommend centrifuged saliva [16]. It seems that both methods are equally valid, even for experiments in which saliva was used as a sample for various tests [14]. Filtration is a simple method that allows a reduction in saliva viscosity and retention of a particle of high impurity [17].

This study has shown that different relationships may exist between mineralized tissues in the CEJ, not only within certain tooth groups, but on various surfaces of any tooth as well, which is in accordance with results of other studies [1,18,19]. Due to the fact that the dentin close to the CEJ may be exposed to the oral environment, many researchers believe that this region should be called the dentin-cement-enamel junction [19].

The majority of available data regarding the CEJ indicate that there are 3 salient morphological interrelations among the mineralized tissue that compose it: cementum over enamel, the edge-to-edge relationship of enamel and cementum, and the presence of gaps between cementum and enamel that expose a strip of dentin [1,19].

In the study conducted by Arambavata et al. [1], in a small number of specimens, the fourth type of tissue interrelationship was also found – cementum overlapping by enamel. Esberard’s morphological finding of control specimens pointed out the presence of the gap with intermediate cementum covering the dentin tubules [9]. SEM analysis in the present study showed 2 types of interrelations of the enamel and cementum – cementum overlaps the enamel and cementum and enamel are in close contact. In 3 samples there was noted a gap between the enamel and cementum, but dentinal tubules were not observed.

The positive control specimens in this study have shown that dentinal tubules are open just below the enamel border, which might be explained by the existence of intermediate cementum on the tooth root surface rather than by the presence of gap before bleaching. This is in accordance with data in the literature indicating that molecular and physical structures of intermediate cementum do not resist enzymatic action and can be easily removed [9,20].

Treatment of samples with tooth bleaching preparations established that there were also changes in anatomic structures composing the CEJ – the enamel showed changes similar to those of type II etching, and it be recognized by its structural units. The cementum showed excess irregularity with numerous defects and uneven and rough surface. In positive control specimens treated with 35% HP, the CEJ consisted of all 3 mineralized dental tissues. Between the enamel and cementum there were dentinal tubules with more or less obliterated orifice. It was not possible to establish if dentine exposure existed at all before bleaching, but it occurred in a higher number of specimens in the positive control group than in specimens not subjected to bleaching.

In the present study, the cementum was more affected by bleaching procedures than was enamel, which was also observed in previous studies [7,9]. This may be attributed to high concentrations of organic components in the cementum, which consists of a cross-linked collagen structure. This tissue is softer and more permeable to a variety of materials as compared to enamel and dentin [7]. According to Rodsten et al. [8], 30% HP treatment may cause alteration in the chemical structure of the dentin and cementum, making them more susceptible to degradation. Also, these results are in accordance with the observation by Zalkind et al. [7] that some bleaching materials that are considered relatively safe for enamel and dentin are not considered to be safe for cementum.

The presence of gaps with dentin exposure suggests that the CEJ is a site strongly predisposed to the development of pathological changes during dental bleaching. Although the external cervical resorption is related to intracoronary bleaching, there is also a strong relation with the CEJ morphology, which is sensitive to vital bleaching agents. A natural anatomic defect of the CEJ can be found in about 10% of all teeth, thus causing dentin to be exposed [21].

Laboratory studies have also demonstrated that the penetration of hydrogen peroxide into the cervical region can be facilitated by cemental root defects or particular morphologic patterns of the CEJ [12,23].

Treatment with fluorides subsequent to the bleaching procedure is efficient in tooth sensitivity reduction. Many in-office or home bleaching sets contain fluoride gels for post-whitening application. With local application of concentrated fluoride the enamel apatite and Ca and P ions are dissolved. F ions are bound to Ca ions, creating CaF2. This compound could be the source of fluoride, which would ensure reduction of sensitivity, increase in micro-hardness and resistance to bacterial acids of enamel tissue [13,16].

According to the study by Cavalli et al. [24], the enamel is susceptible to mineral changes during bleaching treatment, but mineral loss was minimized by the addition of F and Ca to bleaching agents.

Fluoridated CP bleaching gels were able to reduce the loss of micro-hardness and accelerated micro-hardness recovery in the post-treatment phase to a better extent than non-fluoridated gels [12]. This could be due to the fact that fluoride-containing CP bleaching gels induce fluoride acquisition of enamel [25]. According to data in the literature, it may be speculated that the fluoride component of bleaching gels might support the repair of the microstructural defects by the adsorption and precipitation of salivary components, such as calcium and phosphate. Thus, it was shown that susceptibility of bleached enamel is lower for enamel bleached with a fluoride-containing carbamide peroxide bleaching gel [10].

Regarding pH, data in the literature indicate that the application of acid bleaching agents leads to significant enamel alterations with the appearance of erosion and scratches, which was not observed in the samples bleached with neutral or alkaline bleaching agents [26]. Interestingly, adding fluorides as protective ingredients to bleaching agents has raised concerns about potentially adverse interactions between CP and fluorides, and it has been speculated that the whitening efficiency of CP might be impaired by the calcium fluoride layer, while the remineralization potential of fluoride could be hampered by CP [27]. Recent studies, however, indicate that neither post-bleaching fluoridation nor fluoridated bleaching gel impede the active whitening effect [11,13]. Some studies have established that pH of fluoride agents is an important factor. Ferreira et al. [28] showed that the application of acidulated 1.23% fluoride gel on the bleached enamel leads to deterioration of morphological changes, as opposed to the application of 2% neutral fluoride agent. In the present study, fluoride gel was used with approximately neutral pH and containing ACP. According to Tschoppe et al. [15], the varying pH values and the ACP compounds of the bleaching gels clearly affect the remineralization patterns.

Further studies are required to determine the optimal properties of fluoride (concentration, pH, and additional components) incorporated in bleaching gel formulas for maximum tooth whitening and minimum adverse effects.

Conclusions

In spite of limitations which are characteristic for in vitro studies, experimental results show that bleaching gel with fluorides does not change the morphological appearance of the CEJ and represents a better choice than the hard tissues fluoridation process after bleaching.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Arambawata K, Peiris R, Nanayakkara Morphology of the cemento-enamel junction in premolar teeth. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:623–27. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zantner C, Beheim-Schwarzbach N, Neumann K, Kielbassa AM. Surface microhardness of enamel after different home bleaching procedures. Dent Mater. 2007;23:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attin T, Schmidlin PR, Wegehaupt F, Wiegand A. Influence of study design on on the impact of bleaching agents on dental enamel microhardness: a review. Dent Mater. 2009;25:143–57. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delfino CS, Chinelatti MA, Carrasco-Guerisoli LD, et al. Effectiveness of home bleaching agents in discolored teeth and influence on enamel microhardness. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:284–88. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joiner A. Review of the effects of peroxide on enamel and dentin properties. J Dent. 2007;35:882–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kugel G, Petkevis J, Gurgan S, Doherty E. Separate whitening effects on enamel and dentin after fourteen days. J Endod. 2007;33:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zalkind M, Arwaz R, Goldman A, Rotstein I. Surface morphology changes in human enamel, dentin and cementum following bleaching: a scanning electron microscopy study. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1996.tb00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodstein I, Lehr Z, Gedalia I. Effect of bleaching agents on inorganic components of human dentin and cementum. J Endod. 1992;18:290–93. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80956-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esberard R, Esberard RR, Esberard RM, et al. Effect of bleaching on the cemento-enamel junction. Am J Dent. 2007;20:245–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attin T, Kocabiyik M, Buchalla W, et al. Susceptibility of enamel surfaces to demineralization after application of fluoridated carbamide peroxide gels. Caries Res. 2003;37:93–99. doi: 10.1159/000069015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gladwell J, Simmons D, Wright JT. Remineralization potential of fluoridated carbamide peroxide whitening gel. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18:206–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2006.00021_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attin T, Betke H, Schippan F, Wiegard A. Potential of fluoridated carbamide peroxide gels to support post-bleaching enamel re-hardening. J Dent. 2007;35:755–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HP, Chang CH, Liu JK, et al. Effect of fluoride containing bleaching agents on enamel surface properties. J Dent. 2008;36:718–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang J, Park NJ, Hu S, Wong DT. A universal pre-analytic solution for concurrent stabilization of salivary proteins, RNA and DNA at ambient temperature. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschoppe P, Neumann K, Mueller J, Kielbassa AM. Effect of fluoridated bleaching gels on the remineralization of predemineralized bovine enamel in vitro. J Dent. 2009;37:156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren YF, Azadeh A, Malmstrom H. Effects of tooth whitening and orange juice on surface properties of dental enamel. J Dent. 2009;37:424–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanden Abbeele A, Courtois P, Pourtois M. Peroxidase activity loss after filtration and centrifugation of whole saliva. Influence of citrate. J Biol Buccale. 1992;20:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman E, Hargreaves J. Variable cemento-enamel junction in one person. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:93–97. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuvald L, Consolaro A. Cemento-enamel junction: microscopic analysis and external cervical resorption. J Endod. 2000;24:74–77. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison JW, Roda RS. Intermediate cementum. Oral Surg Oral Med, Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:624–33. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plotino G, Buono L, Grande N, et al. Nonvital tooth bleaching: a review of the literature and clinical procedures. J Endod. 2008;34:394–407. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodstein I, Torek Y, Misgar R. Effect of cementum defects on radicular penetration of 30% H2O2 during intracoronar bleaching. J Endod. 1991;17:230–33. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81927-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koulaouzidou E, Lambrianidis T, Beltes P, et al. Role of cemento-enamel junction on the radicular penetration of 30% hydrogen peroxide during intracoronal bleaching in vitro. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12:146–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1996.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalli V, Rodrigues LK, Paes-Leme AF, et al. Effects of bleaching agents containing fluoride and calcium on human enamel. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:e157–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attin T, Albrecht K, Becker K, et al. Influence of carbamide peroxide on enamel fluoride uptake. J Dent. 2006;34:668–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu B, Li Q, Wang Y. Effects of pH values of hydrogen peroxide bleaching agents on enamel surface properties. Oper Dent. 2011;36(5):554–62. doi: 10.2341/11-045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiegand A, Vollmer D, Foitzik M, et al. Efficacy of different whitening modalities on bovine enamel and dentin. Clin Oral Investig. 2005;9:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s00784-004-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Ferreira SS, Araujo JL, Morhy ON, et al. The effect of fluoride therapies on the morphology of bleached human dental enamel. Microsc Res Tech. 2011;74:512–16. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]