Abstract

Genome wide analysis revealed the miR-17/92 cluster as a STAT5 target. This cluster encodes six microRNAs, which predictably target genes that play a role in mammary gland development. In this study we have deleted the miR-17/92 cluster in mammary stem cells and evaluated in the mouse its function during mammary gland development. Loss of the miR-17/92 cluster did not affect mammary development from pre-puberty to lactation. Our studies demonstrated that while expression of the miR-17/92 cluster is under control of the key mammary transcription factor STAT5, its presence is not required for normal mammary development or lactation.

Keywords: STAT5, miR-17/92 cluster, mammary gland

Introduction

The transcription factors Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5A and 5B (STAT5) regulate mammary gland development from alveolar proliferation and differentiation to the establishment of lactation (Cui et al., 2004; Miyoshi et al., 2001; Yamaji et al., 2009). Studies from several laboratories have identified protein-encoding genes that are under STAT5 control, some of which execute STAT5 functions in diverse cell types including T cells (Burchill et al., 2007) and mammary epithelium (Bry et al., 2004). The biological complexity of STAT5’s function invokes the potential participation of microRNAs, whose expression are under STAT5 control.

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules that have the ability to modulate cell functions via posttranscriptional regulation of mRNA (Bartel, 2004; Carrington and Ambros, 2003). More than 1,000 microRNAs are encoded in the mammalian genome (Gao et al.). However, little is known about microRNA loci that are under cytokine and STAT5 control. Since the discovery of the regulatory role of microRNAs in C. elegans in 1993 (Lee et al., 1993) only a handful of studies have been published on the role of microRNA in mammary gland development in general and on the ability of STAT5 to regulate these microRNAs in particular. The miR-17/92 cluster encodes six microRNAs (miR-17, miR-18a, miR19a, mir19b, miR-20a and miR-92a). All members of this cluster are transcribed as a single primary transcript (Lu et al., 2007). In addition, the miR-17/92 cluster is considered to be an oncogene as its members are highly expressed in many cancers (Volinia et al., 2006). Deletion of the miR-17/92 cluster in mice resulted in neonatal lethality with specific defects in heart, lung and B cell development (Ventura et al., 2008). In a study preformed in our lab, we identified miR-17/92 as a potential STAT5 target. To investigate its role during mammary gland development we have now deleted the miR-17/92 cluster in mammary stem cells of the mouse using Cre-mediated recombination.

Results

Identification of miR-17/92 as a STAT5 dependent microRNA

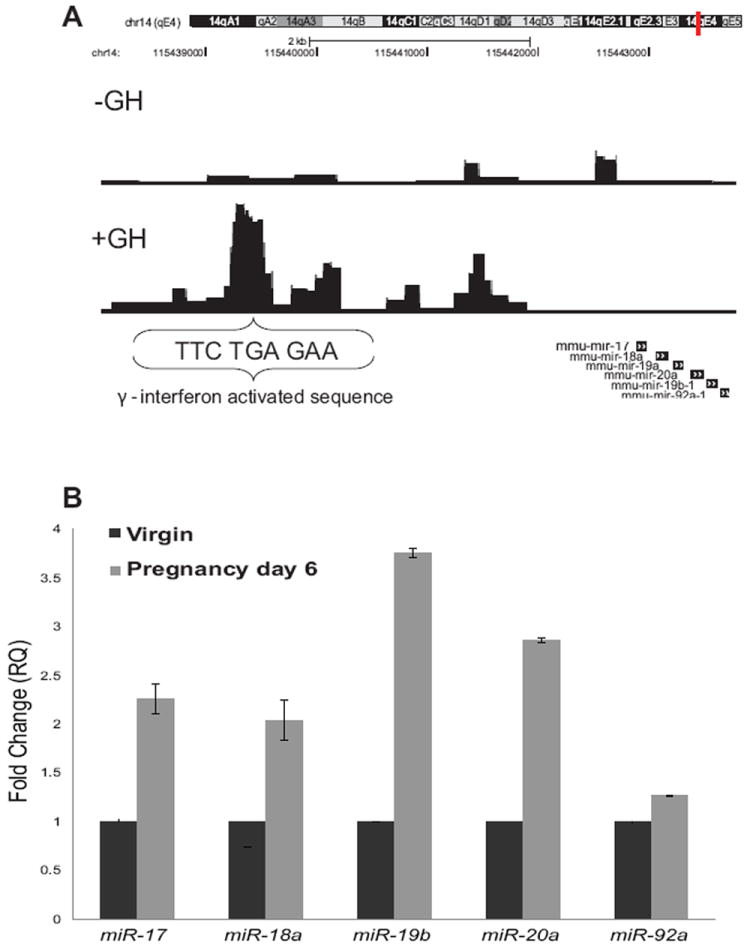

ChIP-Seq experiments revealed STAT5A islands in the miR-17/92 locus. High resolution analysis of the DNA sequence in the STAT5 binding location revealed a highly conserved GAS (γ interferon activated sequence) motif (Figure 1A). Real time PCR analysis of expression levels of the miR-17/92 cluster in mature virgins and at day 6 of pregnancy showed that, compared to virgin mammary tissue, expression of the miR-17/92 cluster (except miR-92a) was elevated 2 to 3.5 fold. At day 6 of pregnancy miR-17 was elevated 2.2 fold, miR-18a 2 fold, miR-19b 3.6 fold and miR-20a ~3 fold (Figure 1B). Based these findings we hypothesized that this cluster may have a biological role during mammary development.

Figure 1. MiR-17/92 cluster is regulated by STAT5.

(A) A view of STAT5A binding on the miR-17/92 locus in MEFs. The insert shows a high resolution view of potential STAT5 GAS sites in the miR-17/92 locus. (B) Expression levels of miR-17/92 cluster members were analyzed in virgins and six days pregnant mice. Values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments. In each analysis virgin mammary tissue was used as the control sample (fold change = 1).

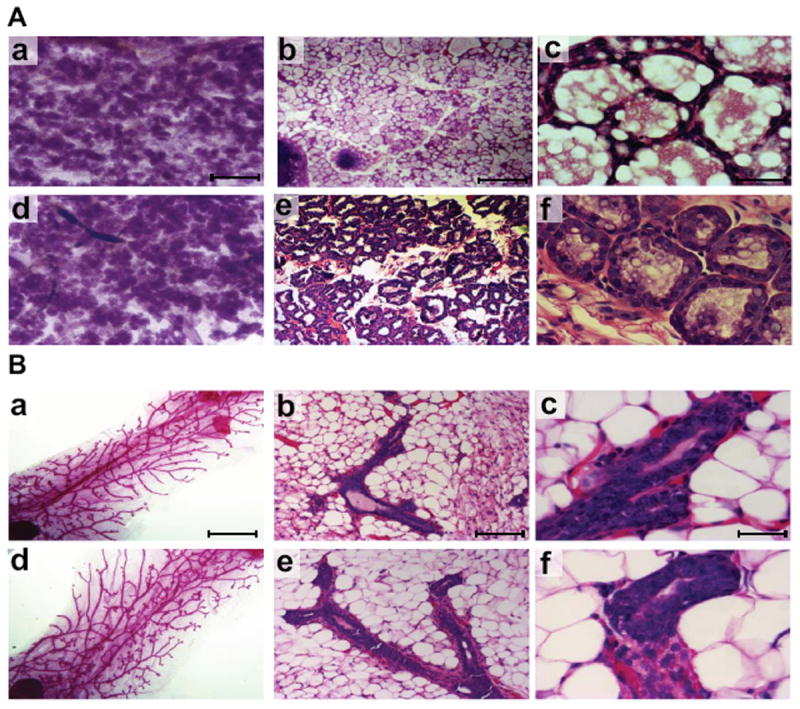

Analysis of miR-17/92 fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mammary tissue from pregnancy to lactation

In order to study the role of miR-17/92 during mammary gland development we used the MMTV CreA transgenic mouse line (Wagner et al., 1997) for the deletion of the miR-17/92 cluster in mammary epithelial stem cells. MiR-17/92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre dams were able to lactate and nurse pups to weaning at the same rate as controls. No mammary gland defects were detected in the whole mount or the histological sections obtained on the morning of delivery (Figure 2A). In addition, whole mount analysis from an early pregnancy time point (day 6) showed no developmental defects (Figure 2B). Therefore we conclude that miR-17/92 is not necessary for mammary development and for the establishment of lactation.

Figure 2. Whole mounts and histological analyses of miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mammary tissues harvested on the day following delivery of pups and on day six of pregnancy.

(A) Whole mount (panel a - miR 17-92fl/fl, panel d - miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections (panel b, c - miR 17-92fl/fl, panel e, f - miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre) of mammary tissues collected after parturition (B) Whole mount (panel a - miR 17-92fl/fl, panel d - miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections (panel b, c - miR 17-92fl/fl, panel e, f - miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre) of mammary tissues collected on day six of pregnancy. Mammary epithelia developed to same extents in the miR 17-92fl/f and in the miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre after parturition and on day six of pregnancy. Scale bar indicates 0.02 mm in a and d, 100 μm in b and e, 10 μm in c and f.

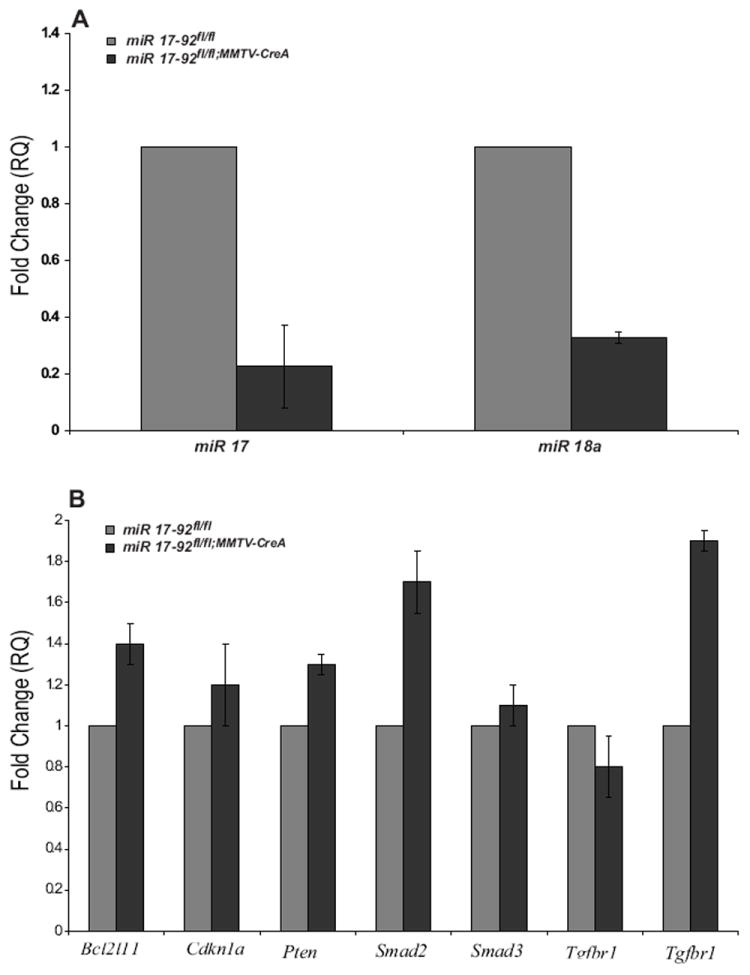

MiR-17/92 cluster target analysis in primary mammary epithelial cells

We verified the deletion of the miR-17/92 cluster in the miR 17/92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mammary epithelium by examining the expression levels of miR-17 and miR-18a in epithelium enriched primary mammary cells. The levels of miR-17 were reduced by ~ 5 fold in the miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre primary mammary cells, while the levels of miR-18a were reduced by ~ 4 fold compared to control cells (Figure 3A). The low levels of miR-17 and miR-18a in the miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre primary mammary cells are due to low levels of contaminating fibroblast that are present in these single cell preparations. For an independent validation of the reduced levels of miR-17/92 we analyzed the expression levels of genes that are considered to be miR-17/92 targets Cdkn1a (p21), Bim (Bcl2l11), PTEN and components of the TGF-β pathway, SMAD2, SMAD3, TGF-β receptor-I and TGF-β receptor-II by real time PCR. Only the expression levels of SMAD2 and TGF-β Receptor-II were higher in primary cells from miR-17/92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre compared to miR-17/92fl/fl mice (more then 1.5 fold), by 1.7 and 1.9 fold respectively, (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. miR-17/92 expression and target analysis in miR 17-92fl/fl:MMTV-Cre primary mammary cells.

(A) Expression of miR-17 and miR-18a in miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre and miR 17-92fl/fl primary mammary cells show decreased levels of miR-17 and miR-18a in the miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre primary mammary cells. (B) Among the predicted targets Bcl2l11, Cdkn1a, Pten, Smad2, Smad3, Tgfbr1 and Tgfbr2 only Tgfbr2 and Smad2 are upregulated by 1.7 and 1.9 fold, respectively, in miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre compared to miR 17-92fl/fl primary mammary cells. In each analysis, the miR 17-92fl/fl primary mammary cells were used as the control sample (fold change = 1). Values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

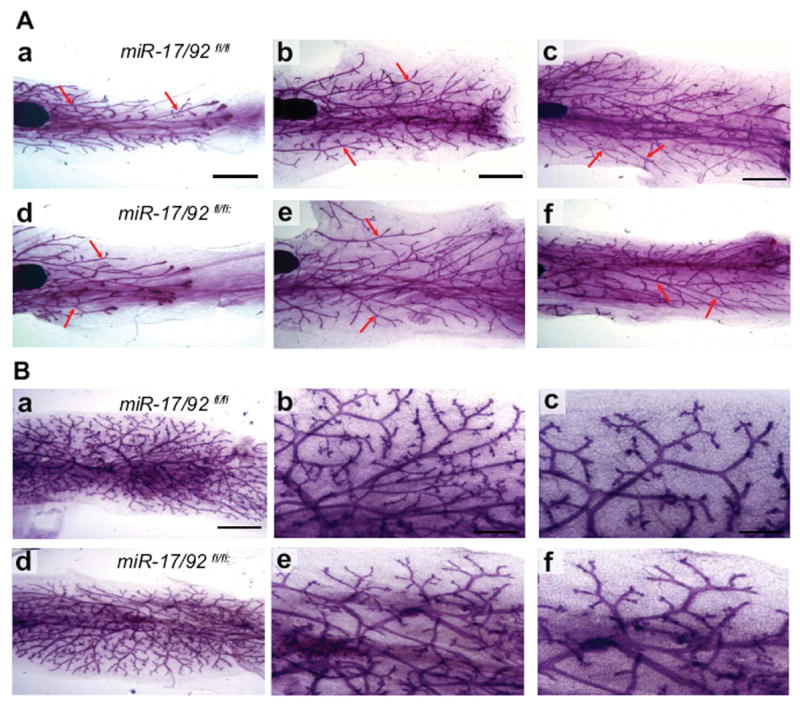

Analysis of miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre mammary tissue during puberty

The TGF-β pathway regulates early mammary gland development (Pierce et al., 1993). Based on our findings that the TGF-β pathway is up regulated in the absence of the miR-17/92 cluster in mammary cells, we decided to study the role of miR-17/92 in the developing mammary gland during puberty. Analysis of mammary tissue harvested from 5, 10 and 14 week old mice showed that miR-17/92fl/flMMTV Cre mammary epithelia exhibited fewer secondary branching at 10 and 14 weeks of age compared to controls (Figure 4A). In order to rule out variations in the secondary branching induced during the estrus cycle, we performed transplantations into nude mice. The transplanted mammary tissues were removed after 6 week of growth in the host. As shown in Figure 4B, miR 17-92fl/fl;MMTV-Cre and control transplants (miR 17-92+/+;MMTV-Cre mice) exhibited equivalent secondary branching. Therefore we conclude that the miR-17/92 cluster is not vital for mammary development at early stages as well.

Figure 4. Whole mount of mammary tissue from at early time points of development.

(A) Whole mount analyses of mammary tissue from miR-17/92fl/fl;MMTV Cre and miR-17/92fl/fl at the age of 5 (panel a and b), 10 (panel b and c) and 14 weeks (panel e and f). Red arrow marks a site of secondary branching. Scale bar indicates 0.02 mm (B) Whole mount analyses of transplanted mammary tissue of control (panel a, b and c) and miR-17/92fl/fl; MMTV-Cre (panel d, e and f) 6 weeks after transplantation. Higher magnification of the whole mounts shown in middle and lower panels. No differences were detected between the miR-17/92fl/fl;MMTV Cre and miR-17/92fl/fl mammary gland at all the time points analyzed and in the transplanted mammary gland. Scale bar indicates 100 μm in a and d, 50 μm in b and e, 25 μm in c and f.

Discussion

Here we have identified for the first time that the miR-17/92 cluster is a cytokine-induced STAT5-dependent microRNA gene and that expression of the entire miR-17/92 cluster (except for miR-92a) increased during pregnancy. These findings support a report that showed increased levels of miRs encoded in the miR-17/92 cluster during puberty and gestation (Avril-Sassen et al., 2009). Based on all of the above we hypothesized that some of STAT5’s function during mammary gland development may be executed by the miR-17/92 cluster. However, deletion of the miR-17/92 cluster from mouse mammary stem cells did not have a negative impact on mammary gland development and function. These mice delivered and lactated normally and no abnormalities were detected in pup growth. Furthermore, analysis of whole mount and histological samples obtained at day 6 of pregnancy did not present any noticeable defects. The lack of any defects in the mammary gland led us to the conclusion that the miR-17/92 cluster is redundant for mammary gland development during pregnancy.

Up to date, about 30 genes are considered to be miR-17/92 targets (Grillari et al., 2010). Some have been shown to be involved in mammary development. For example, miR-17 and miR-20a target Cdkn1a (p21), a cell cycle regulator), miR-17 targets Bcl2l11 (Bim-BCL2 interacting mediator of cell death) and miR-20 and miR-19 target Pten, which regulates growth, adhesion and apoptosis (Cloonan et al., 2008). It was also reported that the miR-17/92 cluster is a regulator of multiple components of the TGF-β pathway (Dews et al., 2010; Mestdagh et al., 2010; Petrocca et al., 2008). Expression analysis of these predicted targets revealed that in the absence of miR-17/92 from mammary epithelium the levels of TGF-β receptor II and SMAD2 are up regulated. Previously it has been shown that excessive activation of the TGF-β pathway in mammary epithelium inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in the epithelial compartment in early mammary development. However, TGF-β transgenic mice eventually developed a normal mammary gland and were able to lactate (Moses and Barcellos-Hoff, 2010; Pierce et al., 1993). On the other hand, TGF-β receptor II deletion in the mammary gland results in lobular-alveolar hyperplasia (Forrester et al., 2005; Moses and Barcellos-Hoff, 2010).

Therefore, we speculated that miR-17/92 may have a role in pre pubertal development. We decided to analyze the ductal development during puberty. While some ductal branching defects were noticed at early stages, the mammary gland transplantation experiments ruled them out. All of the above led us to the conclusion that the miR-17/92 cluster does not affect any aspect of mammary gland development. However, the STAT5-miR-17/92 pathway may have a role in the development of other cells type. For examples, in the immune system miR-17/92 cluster members are highly expressed at the pre-B cell stage. Deletion of the miR-17/92 cluster results in inhibition of B cell development at the pro-B to pre-B transition (Ventura et al., 2008), a phenotype, which resembles the Stat5 deletion in the hematopoietic cells, where early B cell development is impaired in the absence of Stat5 (Dai et al., 2007).

In this study we used the MMTV-CreA line, which deletes floxed sequences in the epithelial compartment of the gland (Wagner et al., 1997). However, the stromal compartment also plays a role in the regulation of ductal development. Stromal TGF-β signaling has been shown to regulate epithelial branching (Crowley et al., 2005). Since the miR-17/92 cluster has been linked to the TGF-β signaling pathway (Dews et al., 2010; Mestdagh et al., 2010) and it has been show that microRNAs plays a role in epithelial-stromal interactions (Ucar et al., 2010), we cannot rule out the possibility that this cluster plays a role in the mammary stromal compartment to regulate epithelial branching

During evolution, gene duplication resulted in two miR-17/92 paralogs, miR-106a/363 and miR-106b/25 (Petrocca et al., 2008). MiR-106b and miR-93 (members of the miR-106b/25 cluster) exhibit the same expression patterns as miR-17/92 cluster (Avril-Sassen et al., 2009). Recent studies have shown that miR-17-92 and its two paralogs are very similar (Ventura et al., 2008) and some of the microRNAs, such as miR-17, miR-26a and miR-106a share the same targets (Trompeter et al., 2011). This suggests that a potential role of the miR-17/92 cluster is masked by compensatory paralogous miRs.

Methods

Generation of miR 17-92bfl/fl;MMTV-Cre and miR 17-92fl/fl;WAP-Cre mice

All animals were handled and housed in accordance with the guidelines of the NIDDK Animal Care and Use Committee and NIH regulations. Transgenic mice carrying the floxed miR-17/92 gene (Ventura et al., 2008) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. MiR 17-92fl/fl mice were mated with the MMTV-Cre transgenic mouse line (Line A) (Ventura et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 1997).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Coupled with Illumina sequencing (ChIP-Seq)

ChIP-Seq experiments were performed as described (Bing-Mei et al., 2012). In brief, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were infected with a retroviral-expression vector carrying a wild-type Stat5a gene. For analysis they were starved for 5 hours and then stimulated for 2 hours with growth hormone (250 ng/ml) or left untreated. The cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and chromatin was extracted. Antibodies against STAT5A (PA-ST5A, R&D System), and IgG (AB-105C, R&D System) were used for precipitation. The ChIP DNA fragments were blunt-ended, ligated to the Solexa paired-end adaptors, and sequenced with the Illumina GAIIX genome analyzer.

Histological analysis

Mammary glands were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and imaged on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam Cc1 and Axiovision software. For whole mount analysis the mammary tissues were dissected and spread on a glass slide. After fixation for 4 hours in Carnoy’s solution, the glands were hydrated, stained with carminalum, dehydrated and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific).

Preparation of enriched mammary epithelial cells

Single cells from mammary glands were prepared as previously described (Yamaji et al., 2009). In brief, mammary glands from virgin female mice at 12-14 weeks of age were incubated for 8 hours at 37°C in complete EpiCult-B medium (supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum) containing 300 U/ml collagenase and 100 U/ml hyaluronidase. After lysis of red blood cells, single cell suspensions were prepared by sequential treatment with 0.25% trypsin for 1–2 min, followed with 5 mg/ml dispase II and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I for 2 min. The cells were filtered through a 70-μm mesh before use. All reagents were from StemCell Technologies Inc. (Vancouver, Canada).

RNA extraction and analysis

MiRNA and mRNA were extracted with miRNeasy system (Qiagen). Expression analysis was performed by using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) for real-time PCR.

Transplantation of mammary epithelia into the cleared fat pad of nude mice

The transplantation was performed as previously described (Miyoshi et al., 2001). In brief, athymic nude mice (3-wk-old) were anesthetized and the proximal part of the endogenous mammary epithelial compartment was removed surgically. Pieces of mammary tissue from mature virgin donor mice (miR-17/92fl/fl;MMTVCre and miR-17/92+/+;MMTVCre mice as controls) were grafted into the cleared fat pads of recipients. 6 weeks after transplantation, transplanted fat pads were harvested from virgin hosts. For whole mounts, mammary glands were removed, fixed in Carnoy’s fixative overnight, stained in carmine alum and mounted.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH.

References

- Avril-Sassen S, Goldstein LD, Stingl J, Blenkiron C, Le Quesne J, Spiteri I, Karagavriilidou K, Watson CJ, Tavare S, Miska EA, Caldas C. Characterisation of microRNA expression in post-natal mouse mammary gland development. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing-Mei Z, Keunsoo K, Ji Hoon Y, Weiping C, Harold ES, Daeyoup L, Hong-Wei S, Lai W, Lothar H. Genome-wide analyses reveal the extent of opportunistic STAT5 binding that does not yield transcriptional activation of neighboring genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012 doi: 10.1093/nar/gks056. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry C, Maass K, Miyoshi K, Willecke K, Ott T, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Loss of connexin 26 in mammary epithelium during early but not during late pregnancy results in unscheduled apoptosis and impaired development. Dev Biol. 2004;267:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan N, Brown MK, Steptoe AL, Wani S, Chan WL, Forrest AR, Kolle G, Gabrielli B, Grimmond SM. The miR-17-5p microRNA is a key regulator of the G1/S phase cell cycle transition. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R127. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-8-r127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley MR, Bowtell D, Serra R. TGF-beta, c-Cbl, and PDGFR-alpha the in mammary stroma. Dev Biol. 2005;279:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Riedlinger G, Miyoshi K, Tang W, Li C, Deng CX, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Inactivation of Stat5 in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy reveals distinct functions in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8037–8047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8037-8047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Chen Y, Di L, Podd A, Li G, Bunting KD, Hennighausen L, Wen R, Wang D. Stat5 is essential for early B cell development but not for B cell maturation and function. J Immunol. 2007;179:1068–1079. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dews M, Fox JL, Hultine S, Sundaram P, Wang W, Liu YY, Furth E, Enders GH, El-Deiry W, Schelter JM, Cleary MA, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. The myc-miR-17~92 axis blunts TGF{beta} signaling and production of multiple TGF{beta}-dependent antiangiogenic factors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8233–8246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester E, Chytil A, Bierie B, Aakre M, Gorska AE, Sharif-Afshar AR, Muller WJ, Moses HL. Effect of conditional knockout of the type II TGF-beta receptor gene in mammary epithelia on mammary gland development and polyomavirus middle T antigen induced tumor formation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2296–2302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Schug J, McKenna LB, Le Lay J, Kaestner KH, Greenbaum LE. Tissue-specific regulation of mouse MicroRNA genes in endoderm-derived tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillari J, Hackl M, Grillari-Voglauer R. miR-17-92 cluster: ups and downs in cancer and aging. Biogerontology. 2010;11:501–506. doi: 10.1007/s10522-010-9272-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Thomson JM, Wong HY, Hammond SM, Hogan BL. Transgenic over-expression of the microRNA miR-17-92 cluster promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation of lung epithelial progenitor cells. Dev Biol. 2007;310:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestdagh P, Bostrom AK, Impens F, Fredlund E, Van Peer G, De Antonellis P, von Stedingk K, Ghesquiere B, Schulte S, Dews M, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Schulte JH, Zollo M, Schramm A, Gevaert K, Axelson H, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. The miR-17-92 microRNA cluster regulates multiple components of the TGF-beta pathway in neuroblastoma. Mol Cell. 2010;40:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Shillingford JM, Smith GH, Grimm SL, Wagner KU, Oka T, Rosen JM, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat) 5 controls the proliferation and differentiation of mammary alveolar epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:531–542. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses H, Barcellos-Hoff MH. TGF-beta biology in mammary development and breast cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;3:a003277. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocca F, Vecchione A, Croce CM. Emerging role of miR-106b-25/miR-17-92 clusters in the control of transforming growth factor beta signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8191–8194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce DF, Jr, Johnson MD, Matsui Y, Robinson SD, Gold LI, Purchio AF, Daniel CW, Hogan BL, Moses HL. Inhibition of mammary duct development but not alveolar outgrowth during pregnancy in transgenic mice expressing active TGF-beta 1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2308–2317. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trompeter HI, Abbad H, Iwaniuk KM, Hafner M, Renwick N, Tuschl T, Schira J, Muller HW, Wernet P. MicroRNAs MiR-17, MiR-20a, and MiR-106b act in concert to modulate E2F activity on cell cycle arrest during neuronal lineage differentiation of USSC. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucar A, Vafaizadeh V, Jarry H, Fiedler J, Klemmt PA, Thum T, Groner B, Chowdhury K. miR-212 and miR-132 are required for epithelial stromal interactions necessary for mouse mammary gland development. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/ng.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Young AG, Winslow MM, Lintault L, Meissner A, Erkeland SJ, Newman J, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Stone JR, Jaenisch R, Sharp PA, Jacks T. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, Wall RJ, St-Onge L, Gruss P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Garrett L, Li M, Furth PA, Hennighausen L. Cre-mediated gene deletion in the mammary gland. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4323–4330. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji D, Na R, Feuermann Y, Pechhold S, Chen W, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Development of mammary luminal progenitor cells is controlled by the transcription factor STAT5A. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2382–2387. doi: 10.1101/gad.1840109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]