Abstract

Objective

Clinical interventions that lengthen life after HIV infection and significantly reduce transmission could have greater impact if more HIV-diagnosed people received HIV care. We tested a surveillance-based approach to investigating reasons for delayed entry to care.

Methods

Health department staff in three states and two cities contacted eligible adults diagnosed with HIV four to 24 months previously who had no reported CD4+ lymphocyte (CD4) or viral load (VL) tests. The staff conducted interviews, performed CD4 and VL testing, and provided referrals to HIV medical care. Reported CD4 and VL tests were prospectively monitored to determine if respondents had entered care after the interview.

Results

Surveillance-based follow-up uncovered problems with reporting CD4 and VL tests, resulting in surveillance improvements. However, reporting problems led to misspent effort locating people who were already in care. Follow-up proved difficult because contact information in surveillance case records was often outdated or incorrect. Of those reached, 37% were in care and 29% refused participation. Information from 132 people interviewed generated ideas for service improvements, such as emphasizing the benefits of early initiation of HIV care, providing coverage eligibility information soon after diagnosis, and leveraging other medical appointments to provide assistance with linkage to HIV care.

Conclusions

Surveillance-based follow-up of HIV-diagnosed individuals not linked to care provided information to improve both surveillance and linkage services, but was inefficient because of difficulties identifying, locating, and recruiting eligible people. Inefficiencies attributable to missing, incomplete, or inaccurate surveillance records are likely to diminish as data quality is improved through ongoing use.

Clinical interventions that are capable of improving the quality and length of life after human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and significantly reducing transmission1–16 have limited population-level impact because many HIV-diagnosed people cannot or do not access HIV medical care. Marks et al. estimated that 72% of people newly diagnosed with HIV in the United States had received medical care for their HIV infection within four months of diagnosis.17 Studies have shown that many of those not entering care soon after diagnosis continue to delay care entry;18–20 evidence suggests that antiretroviral therapy may not restore health as fully when initiated late.21–24

As the capacity of HIV surveillance to monitor care use has increased, some health departments have begun to use HIV surveillance as both a source of feedback to public health workers and health-care providers on rates of linkage to and retention in care and a bridge among health departments, patients, and medical care providers to facilitate case management.25,26 We summarize findings from the Never in Care Pilot Project, which tested the use of case surveillance data to prompt investigation of the system-level barriers and human factors affecting entry to care.

METHODS

In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State to conduct the Never in Care Pilot. State laws in these jurisdictions mandated reporting of either all CD4+ lymphocyte (CD4) or all viral load (VL) values. Health departments sampled people diagnosed from December 2006 to December 2009 and reported to the enhanced HIV/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Reporting Systems (eHARS) in these project areas. Eligible adults were diagnosed ≥90 days previously and had no reported CD4 or VL tests, with the exception of tests in the same month and year as the HIV diagnosis, unless followed by additional CD4 or VL tests. (A test during this period may have been ordered along with confirmatory testing and before referral to care.27) The investigators have described the sampling methods in greater detail in a previously published report.28

Staff investigated the eligibility of sampled people by searching CD4 and VL reports for any evidence of care entry after selection and checking diagnosis dates against available records. Routine matching of surveillance data with vital statistics data, and ongoing interstate efforts to de-duplicate reported HIV cases,29 identified deaths and migration out of the project area, respectively, among sampled people. Those not excluded as ineligible as a result of these efforts were contacted by mail, phone, and home visit—in that order, if possible—depending on the availability of contact information. Contact information was obtained from the surveillance record when available, from diagnostic service providers, or by other means available to the health departments for case investigation, if necessary. Contact attempts continued until six months from the initial contact, after which the case was closed and the person was considered unable to be located.

Interviewers screened potential respondents to confirm eligibility when contact was made. Those determined to be ineligible and who had not yet entered care received referrals to medical services. All those who remained were invited to participate in the interview and fingerstick blood draw. Consenting participants had whole blood collected (250 microliters [μL]) using the Microtainer® tube microcollection device (Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, New Jersey). The CD4 count in whole blood was measured by immunophenotyping with the FACSCaliburTM flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) using the BD MultitestTM CD3/CD8/CD45/CD4 kit (BD Biosciences). HIV plasma VL was measured when a sufficient blood volume was collected using the COBAS® AMPLICOR HIV-1 Monitor Test, v1.5 (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Pleasanton, California).

Incoming reports of surveillance of CD4 and VL tests were prospectively monitored via eHARS through August 31, 2010, to determine if respondents had entered care after they were interviewed. A CD4 or VL test reported to surveillance after the interview was treated in this analysis as the first CD4 count or first VL measurement for (1) people from whom blood was not collected at the interview and (2) those whose blood collected at the interview could not be tested because of insufficient volume or clotting.

Participants were offered an incentive for their participation. All people contacted were encouraged to seek HIV medical care and given information about the benefits of care (a brochure produced by CDC) as well as referrals (i.e., contact information for medical care and other service providers in their area).

Variables

The following information was collected from consenting adults through a 30-minute structured interview: demographic characteristics, barriers to and facilitators of HIV medical care, and general health. We used reported income and number of dependents to determine the percentage of respondents who fell below 300% of the federal poverty level (FPL), a common eligibility criterion for publicly funded care, -according to standardized methods.30 We grouped individual reasons for not entering care into the following categories: financial/insurance, knowledge/information (e.g., believing that there is no need for care if one feels good), psychological (e.g., not wanting to think about HIV status), service organization (e.g., inconvenient clinic location or hours), and other (too sick to initiate care, fully occupied with other responsibilities such as child care, homeless, or no transportation).

Analyses

We analyzed data using SAS® version 9.2.31 We examined frequencies and percentages of responses through univariate and bivariate analyses with Chi-square tests to assess differences in proportions.

RESULTS

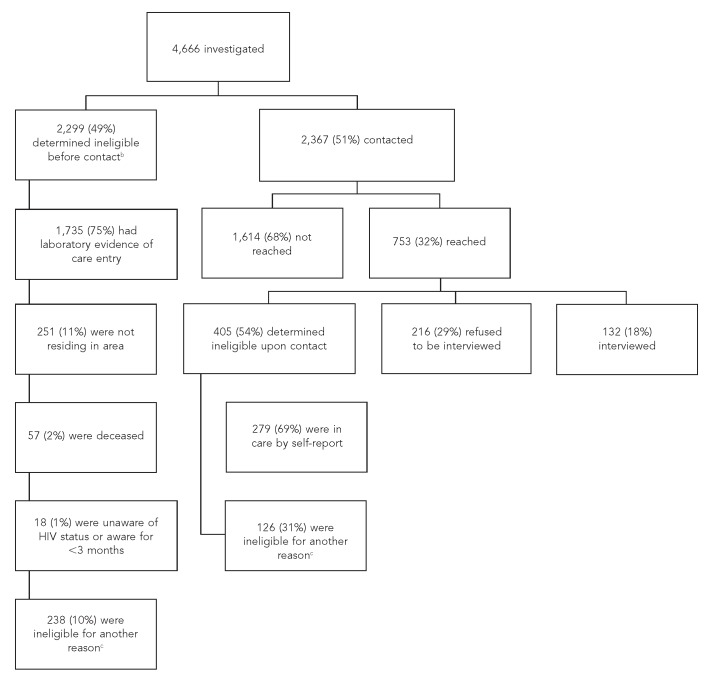

In the five project areas combined, 19,516 adults were diagnosed with HIV infection from December 2006 to December 2009 and reported to eHARS by February 28, 2010. Of these 19,516 adults, 11,156 (57%) had CD4 or VL evidence of care entry and 8,360 (43%) had no evidence of care entry through the month they were eligible for selection. Of the latter, 4,885 were sampled. Of those sampled, 219 were excluded as ineligible after record review because of a diagnosis date that was outside of the eligible date range, leaving 4,666 adults eligible for field investigation. Of those considered eligible for investigation, 2,299 (49%) adults were determined to be ineligible before contact was made. The Figure summarizes the results of the field investigation. Of 132 people interviewed, 105 (80%) provided a blood specimen, a CD4 count was available for 96 respondents (73%), and a VL was available for 90 respondents (68%) (data not shown).

Figure.

Outcomes of case investigation and recruitment of HIV-infected people with no evidence of care entry in five project areas:a Never in Care Pilot Project, 2009–2010

aThe five project areas were Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State.

bOf 4,666 people with no evidence of care entry at the time of selection from the sampling frame, 2,299 people were determined to be ineligible before contact was made: 1,735 people were ineligible because they had laboratory evidence of care entry. Among these, 1,393 had a CD4 or viral load test performed before they were selected, but not reported until after their selection, and 342 had a CD4 or viral load performed after their selection.

cOther reasons for ineligibility included being diagnosed before the eligibility period, not being able to speak English or Spanish, being younger than 18 years of age, or having a CD4 or viral load date before the HIV diagnosis date.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

We found significant differences in characteristics between people who were interviewed and those who were not interviewed (i.e., not contacted or refused the interview), as well as between people who were interviewed and people who had evidence of care entry. As shown in Table 1, information available in eHARS indicated that the majority of respondents were non-Hispanic black (63%), male (75%), younger than 30 years of age (46%), born in the U.S. (82%), and interviewed in Indiana (51%).

Table 1.

Comparison of sampled HIV-infected peoplea who were interviewed with sampled people who were not interviewed and sampled people who were ineligible to be interviewed: five project areas,b Never in Care Pilot Project, 2009–2010

aSampled people were diagnosed with HIV between December 2006 and December 2009 and had no evidence of care entry (includes those with only one CD4 or VL test in the same month as their HIV diagnosis).

bThe five project areas were Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State.

cFor sampled people interviewed, never in care status was confirmed by self-report.

dSampled people not interviewed included 216 people who declined to participate when contacted and 1,614 people not reached through contact attempts (neither group was confirmed to be never in care).

ePeople ineligible because of evidence of care entry included people with >1 CD4 or VL tests unless they had only one test in the same month as their HIV diagnosis.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NA = not available

MSM = men who have sex with men

IDU = injection drug user

CD4 = CD4+ lymphocyte

VL = viral load

Table 2 presents additional characteristics of the respondents. At the time of the interview, 46% were >6 months from their HIV diagnosis. The majority of respondents (60%) had ≤high school education, and most (95%) had incomes of <300% FPL. Blood collected at interview was tested for CD4 for 69 respondents and for VL for 61 respondents; first CD4 and/or VL was available from subsequent monitoring of reports to surveillance for an additional 27 respondents (CD4) and an additional 16 respondents (VL). Of 96 respondents for whom CD4 count was available either through the Never in Care Pilot or a later report to surveillance, 47% had counts of <350 cells/cubic millimeter (mm3) and 20% had counts of <200 cells/mm3; 44% of the 77 people with VL results had a VL of >100,000 copies/milliliter (mL).

Table 2.

Characteristics of HIV-infected people with no evidence of care entrya interviewed in five health project areas (n=132):b Never in Care Pilot Project, 2009–2010

aDiagnosed between December 2006 and December 2009

bThe five project areas were Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State.

cReported behavior prior to diagnosis (respondents could choose more than one category).

dReported income and number of dependents were used to determine the percentage of poverty level for each respondent according to standardized methods. Department of Health and Human Services (US). Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. Fed Reg 2009;74:4199-201. Also available from: URL: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/09fedreg.shtml [cited 2012 Aug 30].

eMcKinney-Vento definition of homelessness: living on the street, staying in a shelter, living in a single-room-occupancy hotel, temporarily staying with friends or family, or living in a car. A person is categorized as homeless if that person lacks a fixed, regular, adequate nighttime residence or has a steady nighttime residence that is (1) a supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living acccommodations, (2) an institution that provides a temporary residence for people who are intended to be institutionalized, or (3) a public or private place not designed for or ordinarily used as a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings (e.g., in an automobile or under a bridge). Taken from: Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, 42 U.S.C. 11301, et seq. (1987).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

FPL = federal poverty level

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

CD4 = CD4+ lymphocyte

mm3 = cubic millimeter

mL = milliliter

Table 3 describes respondents' health and relationship with the health-care system. Twenty-six percent said they felt depressed all or most of the time in the past four weeks, 15% had never received health care for any reason, 71% either had no health insurance or had a gap in health insurance in the past three months, and 38% had a medical care visit after their HIV diagnosis that was not HIV-related and did not lead to care entry.

Table 3.

Health and interaction with the health-care system reported by HIV-infected people with no evidence of care entrya interviewed in five health project areas (n=132):b Never in Care Pilot Project, 2009–2010

aDiagnosed between December 2006 and December 2009

bThe five project areas were Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State.

cReports of CD4 and VL tests received by the HIV surveillance units in participating project areas were monitored for a median of 17 months (range: 1–29 months); median time from interview to first reported CD4 or VL test was 97 days.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

CD4 = CD4+ lymphocyte

VL = viral load

As shown in Table 4, the five most frequently reported reasons for not entering care were lack of money or health insurance (57%), not wanting to think about being HIV-positive (55%), feeling good/healthy (55%), feeling depressed (45%), and not wanting to disclose HIV-positive status (43%). Of those who cited lack of money or health insurance as a reason for not entering care, 97% met a common eligibility threshold for public HIV care (income <300% FPL) (data not shown). For most respondents, barriers to care were multidimensional—only 14% reported barriers in only a single category.

Table 4.

Barriers and facilitators to HIV care reported by HIV-infected peoplea with no evidence of care entry interviewed in five health project areas (n=132):b Never in Care Pilot Project, 2009–2010

aDiagnosed between December 2006 and December 2009

bThe five project areas were Indiana, New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Washington State.

cPercentages add to more than 100% because respondents could select more than one reason.

dUnstable housing, religious reasons, felt sick, and language barriers were each reported by <5% of respondents as reasons for not entering care.

eRespondents were asked, “What, if anything, would make you more likely to start HIV medical care within the next three months?” Sixty respondents who had previously answered that they were very likely to start HIV medical care in the next three months were not asked this question.

fThe following were reported by <5% of respondents as facilitators to HIV care entry: having other responsibilities covered, stable housing, stable mental health, substance use recovery, cure for HIV/AIDS available, if medicines weren't harmful or unpleasant, trustworthy health-care workers, transportation available, convenient clinic hours, convenient clinic location, available appointments, no language barrier, or nothing would facilitate care entry.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Reported CD4 and VL tests were monitored for a median of 17 months (range 1–29 months). Overall, 43 participants (33%) entered care during this period (as evidenced by a CD4 or VL test after the interview). Of those who had a CD4 or VL test after the interview, the median time from interview to first reported CD4 or VL test was 97 days. Of 102 (77%) respondents who reported being fairly to very likely to enter HIV care within the next three months, only 17 (17%) actually did. Among factors respondents said would make care entry more likely, the top two were having sufficient money or health insurance to enter care (33%) and feeling sick (31%).

DISCUSSION

The Never in Care Pilot tested a concept for enhanced surveillance to investigate reasons for delayed initiation of HIV medical care. HIV case surveillance records triggered follow-up and voluntary interviews that provided useful leads for improving linkage to care. However, the tested approach was challenging to implement.

Finding and recruiting those who had been -diagnosed four to 24 months previously was difficult. The degree of difficulty encountered was consistent with some other, similar efforts.32–34 Unless these challenges can be overcome, the surveillance-based follow-up approach may not be cost-effective. Perhaps both contact and response rates might be increased by preparing those who test HIV-positive to expect follow-up contacts that allow them, if they are willing, to share their experiences for the improvement of services and service access, and also to receive referrals to medical care and other services. Strong emphasis on the benefits of early and ongoing HIV care, even for those who feel healthy, might provide a context for follow-up efforts that would more successfully engage those who have delayed starting care.

Starting the follow-up closer to the time of diagnosis proved more successful than subsequent attempts during the pilot. One reason for the low contact rates among those diagnosed less recently was that contact information obtained at diagnosis was frequently incorrect. A report from San Francisco documented follow-up contact and interviews with 76% of 160 newly diagnosed people.26 Contact and response rates varied across project areas participating in the Never in Care Pilot, with the highest rates in Indiana, but none as high as reported by San Francisco. Identifying critical factors leading to high contact and response rates in areas having greater success might allow for improved outcomes elsewhere if the conditions underlying success can be replicated.

Despite the challenges, the Never in Care Pilot demonstrated that interviewing those who have not yet linked to care can complement a practice that is gaining momentum: the use of reported CD4 and VL test results as proxy indicators to estimate how many HIV-diagnosed individuals have initiated HIV care.25 Interviewing those without CD4 or VL evidence of care entry can help to validate these proxy indicators that are increasingly being used to monitor progress toward national linkage-to-care objectives. Such interviews may also provide a more useful description of who is not linked to care and why—information that has implications for improving support for HIV-diagnosed individuals to begin and continue with HIV medical care.

Those who delay entry to care continue to represent a substantial proportion of people recently diagnosed with HIV.17 The delay is lengthy for many of these people.35 There is an ongoing need to understand the reasons for delayed care entry to provide for the service needs of this group. The Never in Care Pilot identified lack of money or insurance as the most commonly reported barrier to care. Almost all (97%) of those who said they had not entered care because they lacked money or insurance appeared to be financially eligible for publicly funded care, according to reported income and number of dependents. The fact that those who appeared to qualify for public services perceived lack of money or insurance to be a barrier to care entry suggests that they may not be aware of their eligibility. What is known about why eligible HIV-diagnosed people do not use HIV medical services is evolving.33,36 Our findings suggest that providing information about public benefits to eligible people may address one possible underlying reason.

To date, with two exceptions,33,37 studies of barriers to HIV care entry have been retrospective.38–44 Never in Care Pilot interviews with people who had not yet entered care at the time of the interview show that barriers to care are multidimensional, and indicate that poverty and mental health problems may be contributing factors, underscoring the importance of supportive services to help with starting and staying in care.

Fragmentation of the health-care system and separate funding streams for prevention and care present challenges to achieving the seamless system advocated in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy to immediately link people to continuous and coordinated quality care when they learn they are infected with HIV.45,46 The Never in Care Pilot identified health-care system missed opportunities and disconnects worthy of further investigation as potential leverage points for improving early linkage-to-care rates. A previously published article about the pilot described missed opportunities for linkage to care at HIV diagnosis.47 Findings presented in this article indicate that non-HIV-related care visits could also provide an opportunity to facilitate entry to HIV care. Almost 40% of the study population received health care after HIV diagnosis, not including urgent care visits; however, they did not start HIV care. An innovative project, the Louisiana Public Health Information Exchange, demonstrates how surveillance data can be used to leverage non-HIV-related care visits in settings with electronic health records.48 Yet, the majority of those we interviewed did not have any medical care visits, which suggests that waiting for such a visit to occur to start HIV care may lead to later-than-optimal HIV care entry, and that approaches such as surveillance-based follow-up may also be needed.

The potential value of surveillance-based follow-up is its promise for identifying where and why problems, such as gaps between testing and care, are occurring area-wide.25 If implemented as a routine part of public health practice, enhanced surveillance involving interviews with people who have not linked to HIV care could catalyze necessary changes in supportive services. As changes are implemented, their impact could be measured by area-wide linkage-to-care rates estimated from case surveillance data. Repeated assessments of what is preventing linkage to care among those who delay care entry, along with information on the extent to which services have changed to meet needs, could provide iterative cycles of feedback that are critical for incremental improvements in linkage to care.

Our findings point to conditions that would increase the efficiency of surveillance-based follow-up. In the Never in Care Pilot, delayed reporting of CD4 and VL tests resulted in misspent effort, leading to the investigation of 405 cases in which a person selected for participation was actually already in care. An expected reduction in reporting delays as health departments complete the transition to electronic reporting of CD4 and VL tests will likely sharpen the focus of future follow-up efforts. In addition to reporting delays, reporting completeness and other data quality issues may affect how well the presence or absence of reported CD4 or VL tests reflects care entry or non-entry. We found that inconsistent reporting of CD4 and VL tests by a laboratory led to selection of people who were already in care; for some people, initial CD4 and VL tests were ordered before referral to care rather than at the first HIV care visit. Identifying these problems strengthened surveillance data or improved understanding of the data, paving the way for more successful follow-up efforts in the future. Finally, if surveillance data are to be useful for follow-up and facilitating linkage to care, the completeness and accuracy of contact information in the case record must also be improved.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. For one, the Never in Care Pilot was a first attempt at using HIV case surveillance data as a trigger for follow-up interviews about barriers to care in the five participating project areas. We did not assess the continuing benefit to surveillance of investigating the absence of reported CD4 and VL testing in people diagnosed with HIV, nor the potential benefit to linkage-to-care rates of repeated cycles of addressing barriers identified. Additionally, respondents may not be representative of all HIV-diagnosed people who have yet to be linked to HIV medical care. Also, people who did not speak English or Spanish were excluded from participation; their barriers to care may be different from those described in this article. Lastly, the five project areas' unequal success with obtaining interviews was likely the result of multiple factors; the project was not designed to identify the relative contribution of different factors in determining response rates.

CONCLUSIONS

The enhanced surveillance concept tested by the Never in Care Pilot was inefficient because many HIV-diagnosed people who delayed care entry could not be found or refused to be interviewed, and because incompleteness, inconsistency, and delays in reporting CD4 and VL tests led to follow-up of a large number of people who were already receiving HIV medical care. However, using surveillance data to identify people for interviews about barriers to care yielded useful information for improving surveillance, and the interviews provided feedback for improving linkage services. Incremental improvements in surveillance, some underway and some resulting from the pilot, raise expectations of greater efficiency of this approach in the future. The responsibility of public health to facilitate access to life-saving treatment among those inadequately served by the health-care system—and to control the spread of HIV—necessitates enhanced surveillance approaches that identify reasons for delayed care entry and suggest possible solutions.

Footnotes

The Never in Care Project Team included: Daniel Hillman, Michael Connor, Cheryl Pearcy, Alicia Anderson, and Marsha Ford of the Indiana State Department of Health; Barbara Bolden, Afework Wogayehu, Josefina Mercedes, and John Ramos of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services; Alan Neaigus, Samuel Jenness, Chris Murrill, Pat Douse, and Arnoud Desir of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Kathleen Brady, Michael Eberhart, Gia Badolato, Anna Follis, Amanda Mazza, and Robert Alston of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health; Maria Courogen, Mark Stenger, Amber Witcher, Elizabeth Mack, and Leslie Pringle of the Washington State Department of Health; Susan Buskin, Jim Kent, Katie Heidere, Hal Garcia-Smith, and Elizabeth Barash of the Department of Public Health–Seattle – King County; Carolyn Dawson, Michael Omondi, and Davis Lupo of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Laboratory Branch; and Jason Reed and Corliss Heath of the CDC, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Behavioral and Clinical Surveillance Branch.

The Never in Care Pilot was approved by the CDC Institutional Review Board (IRB) and local IRBs in participating project areas. This work was presented in part at the National HIV Prevention Conference, August 15, 2011, in Atlanta, Georgia. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: their lives depend on it. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1500–2. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janssen RS, Holtgrave DR, Valdiserri RO, Shepherd M, Gayle HD, De Cock KM. The serostatus approach to fighting the HIV epidemic: prevention strategies for infected individuals. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1019–24. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giordano TP, Suarez-Almazor ME, Grimes RM. The population effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy: are good drugs good enough? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2005;2:177–83. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, et al. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:11–9. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan KJ, Wood E, Craib KJ, O'Shaughnessy MV, et al. Rates of disease progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiating triple-drug therapy. JAMA. 2001;286:2568–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, Jr, Chmiel JS, Lichtenstein KA, Novak RM, et al. AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses in U.S. patients, 1994-2007: a cohort study. AIDS. 2010;24:1549–59. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Rakai Project Study Group. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia PM, Kalish LA, Pitt J, Quinn TC, Burchett SK, Kornegay J, et al. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:394–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coombs RW, Reichelderfer PS, Landay AL. Recent observations on HIV type-1 infection in the genital tract of men and women. AIDS. 2003;17:455–80. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tovanabutra S, Robison V, Wongtrakul J, Sennum S, Suriyanon V, Kingkeow D, et al. Male viral load and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 subtype E in northern Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:275–83. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200203010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernazza PL, Troiani L, Flepp MJ, Cone RW, Schock J, Roth F, et al. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Potent antiretroviral treatment of HIV-infection results in suppression of the seminal shedding of HIV. AIDS. 2000;14:117–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mofenson LM, Lambert JS, Stiehm ER, Bethel J, Meyer WA, 3rd, Whitehouse J, et al. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 185 Team. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:385–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Operskalski EA, Stram DO, Busch MP, Huang W, Harris M, Dietrich SL, et al. Transfusion Safety Study Group. Role of viral load in heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by blood transfusion recipients. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:655–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta P, Mellors J, Kingsley L, Riddler S, Singh MK, Schreiber S, et al. High viral load in semen of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected men at all stages of disease and its reduction by therapy with protease and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Virol. 1997;71:6271–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6271-6275.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health and Human Services (US); National Institutes of Health. Treating HIV-infected people with antiretrovirals significantly reduces transmission to partners: findings result from NIH-funded international study; [press release] 2011 May 21. [cited 2012 Aug 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.nih.gov/news/health/may2011/niaid-12.htm.

- 16.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection in early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw JA, Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons in the United States: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:2665–78. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torian LV, Wiewel EW, Liu K, Sackoff JE, Frieden TR. Risk factors for delayed initiation of medical care after diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1181–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, Lewis R, Savetsky J, Sullivan L, et al. Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:734–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed JB, Hanson D, McNaghten AD, Bertolli J, Teshale E, Gardner L, et al. HIV testing factors associated with delayed entry into HIV medical care among HIV-infected persons from eighteen states, United States, 2000-2004. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;9:765–73. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins GK, Spritzler JG, Chan ES, Asmuth DM, Gandhi RT, Rodriguez BA, et al. Incomplete reconstitution of T cell subsets on combination antiretroviral therapy in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 384. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:350–61. doi: 10.1086/595888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia F, de Lazzari E, Plana M, Castro P, Mestre G, Nomdedeu M, et al. Long-term CD4+ T-cell response to highly active antiretroviral therapy according to baseline CD4+ T-cell count. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:702–13. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200406010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore RD, Keruly JC. CD4+ cell count 6 years after commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with sustained virologic suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:441–6. doi: 10.1086/510746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, Perrin L, Opravil M, Vernazza P, et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:361–72. doi: 10.1086/431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torian LV, Wiewel EW. Continuity of HIV-related medical care, New York City, 2005-2009: do patients who initiate care stay in care? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:79–88. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zetola NM, Bernstein K, Ahrens K, Marcus JL, Philip S, Nieri G, et al. Using surveillance data to monitor entry into care of newly diagnosed HIV-infected persons: San Francisco, 2006-2007. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bamford LP, Ehrenkranz PD, Eberhart MG, Shpaner M, Brady KA. Factors associated with delayed entry into primary HIV medical care after HIV diagnosis. AIDS. 2010;24:928–30. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fagan JL, Bertolli J, McNaghten AD. Understanding people who have never received HIV medical care: a population-based approach. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:520–7. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glynn MK, Ling Q, Phelps R, Li J, Lee LM. Accurate monitoring of the HIV epidemic in the United States: case duplication in the National HIV/AIDS Surveillance System. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:391–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d52a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services (US). Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. [cited 2012 Aug 30];Fed Reg. 2009 74:4199–201. Also available from: URL: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/09fedreg.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 31.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2002. SAS®: Version 9.2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kilmarx PH, Hamers FF, Peterman TA. Living with HIV. Experiences and perspectives of HIV-infected sexually transmitted disease clinic patients after posttest counseling. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:28–37. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollini RA, Blanco E, Crump C, Zuniga ML. A community-based study of barriers to care initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:601–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanner AE, Muvva R, Miazad R, Johnson S, Burnett P, Jackson S, et al. Integration of HIV testing and linkage to care by the Baltimore City Health Department. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:129–30. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181cab134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertolli J, Jenness S, Valverde E, Johnson C, Fagan J. Using surveillance data to monitor missed opportunities for engagement in HIV medical care. Open AIDS. 2012;6(Suppl 1):131–41. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham SO, Sohler NL, Wong MD, Relf M, Cunningham ME, Drainoni ML, et al. Utilization of health care services in hard-to-reach marginalized HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:177–86. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP. Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: results from the Steps Study. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1161–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9778-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner BJ, Cunningham WE, Duan N, Andersen RM, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA, et al. Delayed medical care after diagnosis in a U.S. national probability sample of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2614–22. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, Stein MD, Turner BJ, Crystal S, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37:1270–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein MD, Crystal S, Cunningham WE, Ananthanarayanan A, Andersen RM, Turner BJ, et al. Delays in seeking HIV care due to competing caregiver responsibilities. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1138–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42:1162–74. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKinney MM, Marconi KM. Delivering HIV services to vulnerable populations: a review of CARE-Act funded research. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:99–113. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC, Jr, Troisi CL, Frankowski RF, Hartman CM, et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–83. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moneyham L, McLeod J, Boehme A, Wright L, Mugavero M, Seal P, et al. Perceived barriers to HIV care among HIV-infected women in the Deep South. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:467–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 (Suppl 2):S238–46. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Office of National AIDS Policy (US). National HIV/AIDS strategy. [cited 2012 Feb 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/onap/nhas.

- 47.Garland PM, Valverde EE, Fagan J, Beer L, Sanders C, Hillman D, et al. NIC Study Group. HIV counseling, testing and referral experiences of persons diagnosed with HIV who have never entered HIV medical care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(3 Suppl):117–27. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Herwehe J, Wilbright W, Abrams A, Bergson S, Foxhood J, Kaiser M, et al. Implementation of an innovative, integrated electronic medical record (EMR) and public health information exchange for HIV/AIDS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:448–52. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]