Abstract

The layers of follicular cells surrounding the oocyte and the interactions among them and the germ cells are critical for the successful maintenance of the ovarian functions. We have set up the isolation procedure and culture conditions of sea bass ovarian follicular cells. Their behaviour at three different physiological temperatures (25, 18 and 15 °C) was evaluated by verifying their steroidogenic capacity along time together with the expression of follicular specific genes (cyp19a1, fshr, lhr and star). These characteristics revealed this culture as a good in vitro alternative to short term in vivo studies at the level of the ovarian follicle. Moreover, to evaluate the suitability of this system for gene function studies conditions for transient transfection of plasmid DNA were optimized. Finally, the characteristics of the follicular culture were not affected by freezing and thawing cycles what facilitates the performance of experiments independently of the reproductive season. In conclusion, we have developed an in vitro homologous system that enables functional and gene expression studies and resembles the in vivo situation in the ovarian follicle.

Keywords: Ovarian follicle, Primary culture, Teleosts, Transient transfection

Introduction

The development of several fish genome sequencing projects during the past decade (fugu, tetraodon, zebrafish, medaka and stickleback) combined with the construction of EST libraries from both commercial and model fish species have significantly increased the identification of new fish genes. Nowadays, the emergence of new generation sequencing technologies is producing massive sequence information from a wide number of species, including fish. However, gene sequence similarity among different organisms is not correlated with differences observed at physiological or morphological levels. Therefore, the development of in vitro systems that enable functional studies of the genes of interest has become essential.

In fish, the number of cell lines or primary culture systems is much lower than in mammals. So far (June 2012), in the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, http://www.lgcstandards-atcc.org) there are only 20 fish cell lines out of more than 3,600, and 23 out of over 40,000 in the case of the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC, http://www.hpacultures.org.uk/collections/ecacc.jsp). Although there are cell lines that have not been deposited in these repositories (at least 283 fish cell lines have been established; Fryer and Lannan 1994; Lakra et al. 2011) these numbers are a good reflection of the actual situation, which forces researchers working with fish to use heterologous systems for functional studies.

Regarding our tissue of interest, the ovary, many cell lines have been derived from mammalian species (Havelock et al. 2004). However, despite the availability of several well characterized cell lines for some species such as humans or mice, they do not always maintain the properties of the original tissue. Moreover, the characteristics of a cell line may change with the time in culture or with passages (Kananen et al. 1995; Havelock et al. 2004). These facts make the comparison of the same events with the in vivo tissue more complicated, finally requiring verification through primary cultures of the results obtained with the cell lines. Therefore, as even homologous systems are not always suitable for certain functional studies the use of heterologous systems alone is arguable.

Among the fish cell lines compiled by Fryer and Lannan (1994) and Lakra et al. (2011) there are 8 lines established from ovary: EO-2 from Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) (Chen and Kou 1988), TO-2 from Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) (Chen et al. 1983), TG from tench (Tinca tinca) (Wolf and Mann 1980), PG from northern pike (Esox lucius) (Ahne 1979), CCO from channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) (Bowser and Plumb 1980), KO-6 from sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) (Lannan et al. 1984), ASO from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Wolf and Mann 1980) and JSKG from barred knifejaw (Oplegnathus fasciatus) (Fernandez et al. 1993). These cell lines were established in order to study response to viral infection but the ovarian cell type from which they are derived has not been characterized. This fact combined with the differences among the reproductive systems of fish, makes the development of homologous systems for a particular species essential.

The European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) is a perciform fish highly valued in marine aquaculture whose reproductive physiology is well known. Females present a group-synchronous ovarian development with spawnings in winter (Carrillo et al. 1995; Asturiano et al. 2000). The ovarian follicle represents the essential unit in the ovary and is composed of the oocyte and two layers of somatic cells: a monolayer of granulosa cells, surrounding the oocyte directly, which secretes the basal membrane around which the second monolayer of somatic cells, theca cells, is organised. These somatic cells, the follicular cells, are critical for the successful maintenance of the reproductive cycle in the ovary. They are the targets for the action of gonadotropins, which stimulate the steroidogenic process that regulates oocyte growth and development (Nagahama 1987).

The increasing number of known genes in sea bass in the last years has supported the development of useful tools for the study of reproduction, as for example the recent production of recombinant gonadotropins (Molés et al. 2008, 2011). But still most of the studies on gonad specific genes are limited to the analysis of their expression levels on natural tissue samples or in gonadal samples treated with specific hormones (Rocha et al. 2009; García-López et al. 2011; Molés et al. 2011). Regarding functional studies on gonadal genes, in sea bass, as in most fish species, they are done using heterologous cell lines, mostly of mammalian origin (Rocha et al. 2007; Andersson et al. 2009). The only in vitro homologous system to study sea bass ovary available so far consists of cultures of minced tissue (Molés et al. 2008).

With the aim of providing a homologous cell system suitable for functional and gene expression studies for the sea bass, we have developed a primary culture of ovarian follicular cells and we have characterized it in terms of steroidogenic capability, specific gene expression and transfection conditions.

Materials and methods

Animals

The material for culture were the ovaries of 3–4 year-old European sea bass (D. labrax) females, bred at the facilities of the Institute of Aquaculture of Torre la Sal (East coast of Spain, 40°N, 0°E). The ovaries were in mid to advanced vitellogenesis stage according to Alvariño et al. (1992). Fish were anaesthetized with ethylene glycol monophenyl ether at 0.5 ml/l and sacrificed according to the Spanish legislation for the protection of animals used for experimentation or other scientific purposes.

Tissue collection and isolation of follicular cells

The isolation of follicular cells was based in the protocol developed for carp (Cyprinus carpio) by Stoklosowa and Epler (1985) with some modifications. Ovaries were removed immediately after killing the animal, and washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The connective tissue capsule was removed manually, and the tissue was transferred to Medium 199 (M199) (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) diluted 4:1 with distilled sterile water. Using a large orifice pipette the tissue was vigorously pipetted until separate oocytes surrounded only by the follicular layer were obtained. The suspension of single follicles was washed with sterile PBS three times. Follicles were transferred into an Erlenmeyer flask and PBS was replaced by a 0.25 % trypsin solution. Trypsinization was carried out at 37 °C, twice for 20 min and once for 10 min. After each incubation time, the supernatant was removed and trypsin activity was inhibited with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). Supernatant fractions (containing the follicular cells) were pooled and filtered through a 100 μm pore size filter. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 200g for 15 min and washed twice with M199.

Cell culture

Cells were cultured as monolayers in M199 supplemented with 10 % FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Invitrogen Corp). Three different growth temperatures were tested: 25 °C with 5 % CO2, 18 and 15 °C. Culture medium was replaced every fourth day. Follicular cells were frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen using a freezing solution consisting of 10 % DMSO as cryoprotectant and 90 % FBS (Simione and Brown 1991).

Steroid analysis

Culture medium was collected every 4th day for 16 days and saved for further analysis of steroid production. When indicated the steroid precursor 1 μM 4-androstene-3,7-dione (androstenedione) (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the culture medium as a single dose, after which medium was saved and replaced with fresh medium without precursor every 24 h for 4 days.

Testosterone (T) and estradiol (E2) levels were determined using specific immunoassays (EIA) developed for sea bass (Rodríguez et al. 2000; Molés et al. 2011). Medium samples were assayed at a 1–50-fold dilution.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc. Cincinnati, OH, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA, using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp.) and random hexamers. 1 μl of cDNA was used as template for PCR. Gene specific primers (Table 1) were selected to amplify intron containing regions, so that genomic DNA contamination could be detected. PCRs consisted of 40 cycles as follows: A series of touchdown cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, the highest annealing temperature for 30 s (Table 1) and 30 s at 72 °C. The annealing temperature was decreased 0.5 °C per cycle. The remaining cycles consisted of 94 °C for 30 s, the lowest annealing temperature for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. 18S ribosomal RNA was amplified as internal control for 18 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 45 s and 72 °C 45 s.

Table 1.

Gene specific primersa used for RT-PCR

| Gene | Sequence (5′ → 3′)/Name | Touchdownb Annealing T |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cyp19a1 | (F) | TCGACATCTCCAACAGACTCTTC | 66 °C max → 60 °C min | |

| (R) | CTGCAACCTCTGAAGGTCCCC | |||

| star | (F) | CCTCCTGCTTCCTGGCGGGA | 66 °C max → 60 °C min | |

| (R) | GCATCTTGTGTCAGCAGGCATG | |||

| fshr | (F) | ATCAAATGTGGAGTGTGGGCTC | 66 °C max → 60 °C min | |

| (R) | TCTCCAGCTTGTCGTTCTCCC | |||

| lhr | (F) | lhr35 | 66 °C max → 60 °C min | Rocha et al. (2007) |

| (R) | lhr23 | |||

| foxl2a | (F) | CCCACCCAAGTACCTGCAATCT | 68 °C max → 58 °C min | |

| (R) | TAAATATCAATCCTCGTGTGTAACG | |||

| wt1b | (F) | GGTAGCTGGTATTGCTCCACCA | 68 °C max → 58 °C min | |

| (R) | TGTGTCTGCGCTGGTGCCTCTT | |||

| amh | (F) | 5-AMH1 | 66 °C max → 56 °C min | Halm et al. (2007) |

| (R) | 3-AMH5 | |||

| 18S | (F) | TCAAGAACGAAAGTCGGAGG | 57 °C | Halm et al. (2004) |

| (R) | GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA |

F Forward primer, R reverse primer

aPrimer pairs were designed or selected from different exons to differentiate genomic DNA contaminations, with the exception of those for foxl2a, an intronless gene

bMaximum and minimum temperatures achieved during the annealing step are indicated for each primer pair

Real time quantitative RT-PCR assays

cDNA samples were assayed on an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with default settings in 96 well optical plates. Each 25 μl real time PCR reaction contained the corresponding amount of specific primers and fluorescent probe for the sea bass genes fshr, lhr, star, cyp19a1 or 18S rRNA, according to Rocha et al. (2009), in 1× ABgene’s Absolute™ QPCR Mix (Advanced Biotechnologies Ltd., Epsom, UK). Serial dilutions of plasmids containing each of the genes analysed were used as standard curves. All samples and standards were run in triplicate. Data were analysed with the iCycler iQ™ software (version 3.0.6070) and expression levels of each gene were normalised against the 18S rRNA expression.

Transfection conditions

The following plasmids were used as DNA for transfection: pRL-CMV (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA), which contains the Renilla reniformis luciferase gene under the control of the CMV promoter/enhancer; and pCMVtk-GFP that constitutively expresses GFP to enable a visual observation of the transfection efficiency.

Transient transfections were carried out in 48 well plates with 5 × 105 cells per well. Three transfection systems were tested: Lipofectamine (Invitrogen Corp), Fugene or Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and a modified calcium phosphate method (Chen and Okayama 1987). Lipofectamine transfections were carried out following manufacturer’s guidelines. The DNA:Lipofectamine (μg:μl) ratios tested were 0.13:0.425 and 0.29:0.85 per well. For Fugene transfections, according to the producer’s instructions, 3:1, 6:1 and 9:1 ratios of Fugene:DNA (μl:μg) were tested and 3:1, 3:2 and 6:1 for Fugene 6. For all ratios 0.126 μg of DNA per well were used. In the case of the calcium phosphate method cells in each well were transfected with 0.34 μg of DNA.

In a first step, the pCMVtk-GFP plasmid was used to estimate the performance of each transfection method and thereafter, transfection optimization was carried out using the pRL-CMV plasmid. GFP expression was monitored by means of a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71). Luciferase activity was analysed using the Dual Reporter Luciferase Assay System (Promega Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and the light emitted was measured in a luminometer Junior, EG&G, Berthold, Bad Wildbad, D).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of data were performed using SigmaStat 3.5 (Systat Software, Inc.). Significant differences in steroid production were identified by one-way analysis of the variance (ANOVA) followed by the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison procedures. When required, data were ln-transformated prior to analysis to ensure normality and homoscedascity. In all tests, differences were accepted as statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Cell culture

The number of follicular cells obtained in different isolation procedures depended on the stage of gonadal development of the females. Cultures prepared from 35 mL of isolated follicles resulted in the highest number of cells (3.88 × 108–3.97 × 108 cells) when mid-vitellogenic females were used and the lowest (2.86 × 107–9.25 × 107 cells) in the case of advanced vitellogenic females.

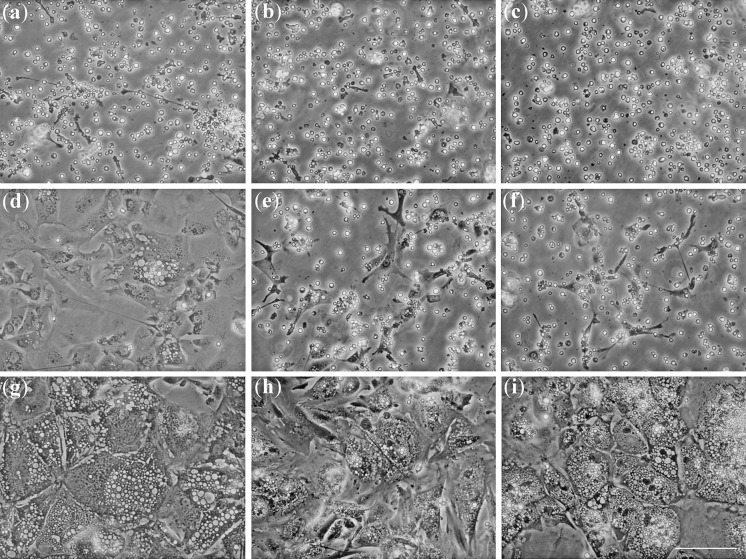

To determine the behaviour of this primary culture at different physiological temperatures, the follicular cells were incubated at: 25, 18 and 15 °C. Cells adhered to the culture surface 24–96 h after plating at 25 °C, initially as small fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 1a) that grow acquiring a cuboidal shape until full confluence was reached what occurred after 5–8 days of culture at 25 °C (Fig. 1d). At this stage cells presented granulated cytosol and from this point onwards the cells suffered an intense process of vacuolization. Cultures at 18 and 15 °C had a similar behaviour although more extended in time in an inverse correlation to the temperature (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Appearance of sea bass follicular cells along time in culture at different temperatures. From left to right cells were cultured at 25 °C (a, d, g), 18 °C (b, e, h) and 15 °C (c, f, i). Photographs were taken after 2 days (a, b, c), 7 days (d, e, f) or 24 days (g, h, i) of culture. Fibroblast-like cells can be observed after 2 days at 25 °C (a) and until 7 days at 15 °C (f). Vacuolization of the cells is clearly visible after 7 days of culture at 25 °C (d) or at any temperature after longer cultivation periods (g, h, i). Scale bar 100 μm, all pictures were taken under the same magnification (×10)

Cell proliferation was observed at the lower temperatures (15 and 18 °C) for approximately 2 months along which up to three doublings were carried out. After the proliferating period, alive cells attached to the culture surface could be observed for three more months. Cells attached tightly to the culture surface at any temperature, and trypsin treatments were needed to dissociate them. However, at 25 °C trypsinization produced a high mortality rate even in freshly seated cells, and consequently cell proliferation at 25 °C could not be assessed. Moreover, at this temperature cultures could only be maintained for approximately 1 month. After this period a fungal contamination recurrently appeared despite the presence and renewal of amphotericin B in the culture medium.

In order to ensure the availability of this primary culture at any time of the year, the possibility of freezing and thawing the follicular cells was evaluated. Therefore, cells were frozen, kept in liquid nitrogen (several months), then thawed and replated. Although a slight mortality (4 %) could be observed after this process, cells could be cultured and transfected in the same conditions as described for fresh cultures.

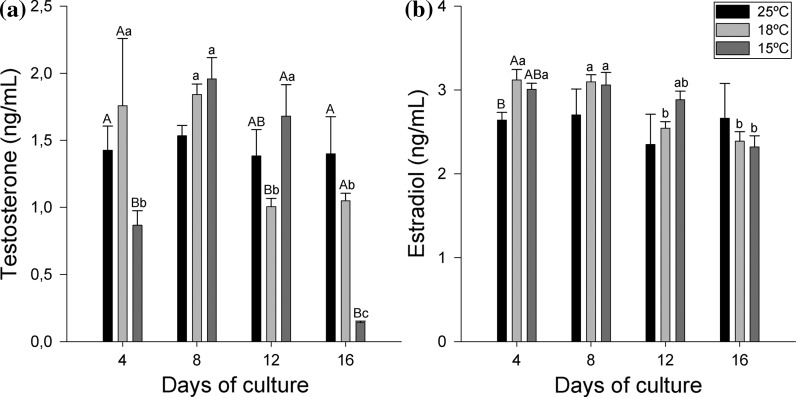

Steroid production

To test the steroid production capability of the follicular culture, both T and E2 were measured in the culture medium during 16 days (Fig. 2). T levels followed a temperature-biased behaviour (Fig. 2a). At 25 °C the follicular cells maintained steady levels of T with no significant differences along time, while at 18 °C high T levels were observed until day 8 followed by a significant decrease that resulted in lower levels in the second half of the study. A different pattern was observed at 15 °C in which lower T production was detected at day 4 that rose significantly by day 8, remained high until day 12 and dropped drastically on day 16.

Fig. 2.

Time-course production of T (a) and E2 (b) by follicular cells cultured at different temperatures (25, 18 and 15 °C). Cells were cultured in 24 well plates 9.2 × 105 cells per well. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three separate wells. Uppercase indicate differences among temperatures for a same sampling time. Lowercase indicate differences among sampling points for a given temperature

E2 production (Fig. 2b) of the cultures at 25 and 18 °C was correlated with the T levels detected. No significant differences during the experiment were found at 25 °C, but a significant decrease between days 8 and 12 took place at 18 °C. However, at 15 °C the follicular culture produced high E2 levels from the first sample point, beginning to decrease at day 12, and leading by day 16 to values significantly lower than those observed at the beginning of the experiment.

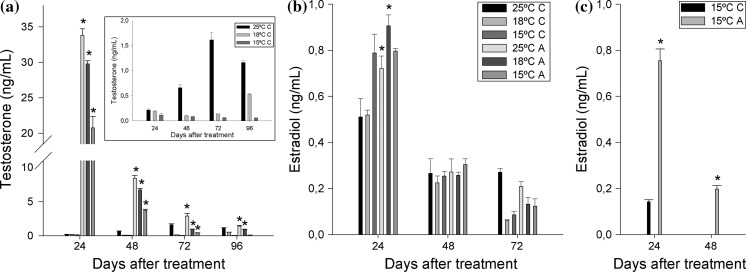

The ability of the follicular culture to complete steroidogenesis, with an exogenous precursor as substrate, was tested by adding androstenedione into the culture medium. In the control cultures, T significantly increased until 72 h to decrease thereafter at 25 °C (Fig. 3a). T levels at 18 °C maintained steady levels that rose at 96 h while no changes were detected at 15 °C. In the case of E2 production in the absence of exogenous precursors, it decreased with the time of culture at any temperature tested to attain undetectable levels at 96 h (Fig. 3b). The only exception observed was a sustained E2 production at 25 °C from 48 to 72 h that dropped thereafter. Independently of the culture temperature, the addition of androstenedione produced a sharp and significant increase of T levels 24 h after the treatment (Fig. 3a) and showed a steady and significant decrease thereafter, as no more androstenedione was added to the culture medium after the initial dose. At the end of the experiment (96 h) T levels in cells cultured at 15 °C had reached basal levels while those of cells cultured at 18 and 25 °C were significantly higher than their respective untreated controls. Although the production of T in androstenedione-treated cells showed a similar pattern at every temperature, the amount of T produced showed a direct correlation with the culture temperature, in this way, the cells cultured at higher temperatures produced higher amounts of T than those maintained at lower temperatures during the whole experiment. When E2 levels were evaluated (Fig. 3b), the androstenedione treatment at 25 and 18 °C resulted in significantly higher E2 levels than in their respective controls 24 h after precursor addition. However, no statistical differences were found between treatments and temperatures at 48 h. In the case of cultures at 15 °C, androstenedione-treated and control cells produced the same levels of E2 at 24 h, and these were similar to those observed in treated cells at 18 or 25 °C and significantly higher than their controls.

Fig. 3.

Time course of steroid secretion by androstenedione-treated follicular cells [A] at different temperatures (25, 18 and 15 °C) compared to the levels in untreated cells [C]. a T levels with an inset graphic reflecting the T levels only in the control group and b E2 levels in the culture medium. The legend in panel b is applied also for panel a. c E2 production at 15 °C 12 days after the first treatment. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three replicates. Asterisks represent significant differences between the androstenedione treated cells and the controls for the same temperature and sampling point

In order to verify the results obtained after androstenedione addition on E2 production at 15 °C, this treatment was performed for a second time with the same follicular culture 12 days after the first treatment (Fig. 3c). Although E2 levels in control wells were lower than those observed in the first treatment, androstenedione-treated cells produced similar amounts of E2 at 24 h than those observed in the first treatment. These levels dropped by 48 h to almost basal levels to be out of the limits of detection of the assay there after. In the case of control cells E2 levels were also undetectable after 24 h.

Gene expression

In order to further ensure that the cell types present in this primary culture were those comprising the follicular layer, the expression of several genes characteristically expressed by ovarian granulosa or theca cells was evaluated by RT-PCR in cells cultured at 25 °C. DNA fragments were successfully amplified for fshr, lhr, cyp19a1, foxl2a, wt1b, star, amh and 18S (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Gene expression by the follicular culture. a RT-PCR amplification of several genes specifically expressed by granulosa or theca cells (fragment size): cyp19a1 (450 bp), star (291 bp), fshr (430 bp), lhr (328 bp), foxl2a (414 bp), wt1b (220 bp), amh (302 bp) and 18S (484 bp). FC follicular cells, NC negative control. b Relative changes in expression of star, cyp19a1, fshr and lhr with time of culture at different temperatures (black bars 25 °C, grey bars 15 °C). Values are shown as mean ± SEM of three replicates. Expression values are normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed as a percentage of the highest value (set as 100) which corresponds to cells cultured at 15 °C for 4 days in every gene. Letters indicate differences along the experiment for a given temperature. Asterisks represent significant differences between temperatures for the same sample point

The low expression levels observed for cyp19a1 led us to investigate the gene expression dynamics during the time of culture of these cells. Particularly, we evaluated through real time RT-PCR the expression of genes involved in the steroidogenic cascade, cyp19a1 and star, and in the response to gonadotropins, fshr and lhr. The expression levels of the four genes (Fig. 4b) decreased with time of culture both at 25 and at 15 °C, although significantly higher values were observed for all of them when the cells were cultured at 15 °C. In the case of star mRNA, a steady decrease was observed for both temperatures until day 16. Expression of cyp19a1, fshr and lhr in cells cultured at 15 °C also showed a steady decrease throughout the analyzed time, while in the cultures maintained at 25 °C expression levels of the three genes dropped drastically at day 8. Cyp19a1 continued decreasing until day 12 and remained steady there after at 25 °C while fshr kept decreasing until day 16. In the case of lhr no expression was detected from day 8 onwards at 25 °C.

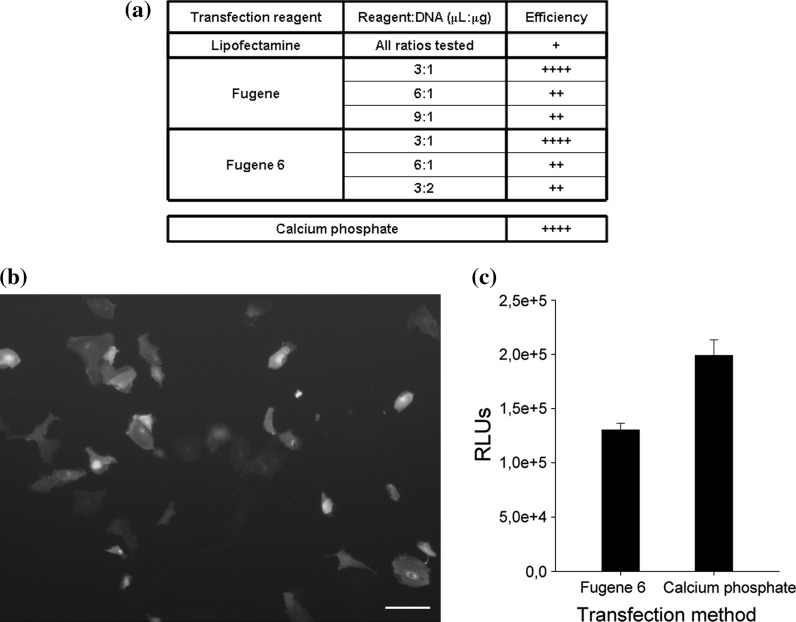

Optimization of transfection conditions

In order to analyse the suitability of the primary follicular culture for gene function studies several transfection systems were evaluated. To this aim the pCMVtk-GFP plasmid was transfected into the cells at 25 °C and transfection efficiency was evaluated through visual observation of green cells under a fluorescent microscope.

When Lipofectamine reagent was used only a few isolated green cells could be observed 48 h after transfection in any of the conditions tested. After this point cells started to die without any increase in the number of green cells. In transfections with the Fugene reagent, very few green cells were detected when 6:1 and 9:1 (Fugene: DNA) proportions were used (Fig. 5a). However, good transfection efficiencies were obtained with the 3:1 ratio where the number of green cells reached its maximum within 72–96 h after transfection, depending on each particular culture. Fugene 6 gave similar results to those observed with Fugene when 3:1 proportions were employed, whereas any other ratio tested resulted in very low transfection efficiencies. Finally, the calcium phosphate method yielded similar results to those obtained with Fugene or Fugene 6 in a 3:1 ratio. Figure 5b shows an example of cells 96 h after transfection of pCMVtk-GFP with the calcium phosphate method. Transfection efficiency was also verified using the pRL-CMV plasmid. Analysis of the luciferase activity revealed values in a range between 1.3 × 105 and 2 × 105 (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Transient transfection efficiency of the follicular culture. a The panel reflects the efficiencies observed under each of the transfection conditions tested. Cells were transfected with the pCMVtk-GFP plasmid and efficiencies were evaluated in terms of appearance of green cells. b Sea bass follicular cells transiently transfected with the pCMVtk-GFP plasmid. Microscopic observation under a fluorescent microscope to assess GFP presence. c Luciferase activity (RLU) after transfection of the primary culture with the pRL-CMV plasmid whether with the Fugene 6 reagent of the calcium phosphate method. (Color figure online)

When the transfection conditions listed above were tested in cultures maintained at lower temperatures, no green cells were observed during 5 days following transfection

Discussion

The development of this primary culture of sea bass ovarian follicular cells, and the feasibility of DNA transfection, provides a suitable in vitro system for functional and expression studies of gonadal genes in fish, which in most cases have been restricted to the use of heterologous cell lines. Although ovary is the most commonly cultured tissue in fish, the particular cell type from which these ovarian lines are derived is not known. Furthermore, in some cases they come from fish too evolutionarily distant to allow heterologous experiments.

The sea bass follicular cells adapted well as an adherent monolayer culture and adopted morphologies that resemble those of other mammalian and piscine ovarian primary cultures (Anderson et al. 1987; Benninghoff and Thomas 2006). The vacuolization observed in the cells with culture time could be associated with the presence of amphotericin B in the growth medium (Lundgren and Roos 1978) or to cell degeneration. Cells cultured in absence of the antimycotic underwent the same process, thus excluding amphotericin B as cause of vaculolization (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that the occurrence of vacuoles is due to the cells entering apoptosis, what has been observed in other ovarian primary cultures (Pregel et al. 2007; Sharma and Bhardwaj 2009).

The cultured cells expressed both gonadotropin receptor genes, fshr and lhr, as well as the genes for P450 aromatase, star and the transcription factors foxl2a and wt1b, thus confirming the follicular origin of the cultured cells. In mammals, the expression of fshr is restricted to granulosa cells while lhr is expressed by both granulosa and theca cells (Camp et al. 1991). However, in fish a study carried out in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) revealed that fshr is expressed by granulosa, theca and interstitial connective cells while lhr is expressed only by granulosa cells (Miwa et al. 1994). In Atlantic salmon both receptors were expressed by both granulosa and theca cells (Andersson et al. 2009). Cyp19a1, coding for the gonadal aromatase, is widely accepted as a marker of granulosa cells (Leung and Armstrong 1980), although it has been described also in theca cells in medaka (Oryzias latipes) (Nakamura et al. 2009). Star transcripts are present in both theca and granulosa cells in fish (Kleppe 2009) and mammals (Kiriakidou et al. 1996). Finally, in the case of the transcription factors analyzed, foxl2 is known to be expressed in granulosa cells in mammals (Crisponi et al. 2001) and in fish such as tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) (Wang et al. 2007), medaka (Nakamoto et al. 2006) and even in hermaphrodite species such as the protogynous wrasse (Halichoeres trimaculatus) (Kobayashi et al. 2010). Wt1 is expressed by granulosa cells in mammals (Pelletier et al. 1991; Hsu et al. 1995). To our knowledge cellular localization of its expression in adult fish has only been investigated in the ovary of two species, Squalius alburnoides and Squalius pyrenaicus, but the expression levels were too low to determine the expressing cell types (Pala et al. 2009). Altogether these results demonstrate that our primary culture is composed by follicular cells of the ovary, granulosa and probably theca cells.

One of the main problems observed in established mammalian granulosa cell lines is the maintenance of the sensitivity to gonadotropins probably due to the loss of gonadotropin receptors (Kananen et al. 1995). Besides, it has been observed in fish (Stoklosowa and Epler 1985; Benninghoff and Thomas 2006), as in other vertebrates (Stoklosowa et al. 1982) that estradiol synthesis capacity is lost with culture time in primary granulosa and theca cell cultures, and this is likely due to a loss in aromatase expression. In order to evaluate the suitability of the sea bass follicular culture along time, mRNA expression studies of aromatase and gonadotropin receptors were carried out. Expression levels of star were also evaluated as this gene codes for a key protein in the acute regulation of steroidogenesis, delivering cholesterol to the inner mitochondrial membrane, which constitutes a rate-limiting step in steroid biosynthesis (Manna et al. 2009). A progressive decrease was observed for the four analysed genes both at 15 and 25 °C. This decrease was more remarkable at 25 °C leading to basal levels of fshr and cyp19a1 and to non-detectable lhr expression by day 8. It is worth noting that the expression levels detected were significantly higher at 15 °C for the three genes. This is consistent with the in vivo situation, as the spawning period of sea bass takes place in winter when the water temperatures are lower, and places this follicular primary culture as a good alternative to in vivo studies at short term at 15 °C (8–12 days of culture) and even at 25 °C (within the first 4 days of culture).

The characteristics of this cell culture were also evaluated in terms of their steroidogenic capacity. Both T and E2 were secreted into the culture medium at any of the physiological temperatures tested. The observed pattern of T secreted to the culture medium every 24 h is consistent with the results obtained in primary cultures of follicular cells in other fish species, as Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulates) (Benninghoff and Thomas 2006) and carp (Epler et al. 1997), in which high T levels were found from 3 to 4 days of culture onwards, respectively. However, in the case of sea bass the increase of T levels was dependent on the temperature, and appeared delayed in an inverse correlation with the temperature of cultivation. Although no rise in T secretion was observed for 15 °C, based on the results obtained for 25 and 18 °C, we can not rule out the possibility of an increase at this temperature with longer times of culture. In the case of E2 production by fish primary cultures, a sharp decrease has been described for carp after 4 days in culture (Stoklosowa and Epler 1985; Epler et al. 1997) and a decrease in E2 synthesis with culture duration is described for Atlantic croaker (Benninghoff and Thomas 2006). This is correlated with the decrease in E2 production observed for sea bass follicular cells and that could be attributed to the decrease observed in cyp19a1 expression with time of culture. It has been demonstrated in fish as in mammals that steroid production by primary cultures of follicular cells reproduce the in vivo situation at the time of tissue collection for 48 h (Szoltys et al. 1982; Galas et al. 1999). Thus, all these results indicate that this primary culture could be a valuable tool for the study of metabolic routes taking place in the ovarian follicle at short culture times.

The steroidogenic capacity of the culture was also evaluated in longer culture times (up to 16 days). Our experience has demonstrated that medium replacement induce changes in gene expression (unpublished results). With the aim of avoiding any interference in the steroid production this experiment was carried out without medium renewal. Although we cannot affirm that the steroid levels measured from day 8 onwards are completely the result of de novo synthesis, the absence of a sustained pattern of accumulation in T levels demonstrates that T is been actively aromatized. Moreover, the decrease in T secretion observed with long culture times at low temperatures is probably derived from a progressive decrease in the availability of steroid precursors in the follicular cells. This fact also demonstrates that the T amounts measured along this experiment resulted, at least partially, from new T synthesized by the follicular cells. E2 production did not show an accumulative pattern either, instead, high E2 levels were detected in the culture medium of the sea bass follicular cells that decreased after 8 days of culture at lower temperatures as the E2 precursor, T, decreased. However, it has been demonstrated that E2 is not the only metabolite of T in granulosa and theca cells (Moon and Duleba 1982) and this, combined with the absence of increasing levels of E2 suggests that other metabolites, such as estrone, could be accumulating in the culture medium.

Addition of androstenedione to the culture medium, together with a daily analysis of the steroids secreted, showed that this primary culture has ready all the machinery to complete steroidogenesis from an exogenous precursor, resulting in a significant increase of both T and E2 24 h after the addition of androstenedione. Indeed, T production kept significantly higher than in their respective controls until 72 h, while the increase of E2 in androstenedione treated cells disappeared 48 h after treatment. Interestingly, at the beginning of the experiment E2 production in non treated cells grown at 15 °C was higher than in those cultured at higher temperatures. This is consistent with the higher aromatase expression observed in follicular cells grown at low temperature (15 °C), but surprisingly, androstenedione addition did not further increase E2 production at this temperature, as it did at 18 and 25 °C. On the other hand, when androstenedione was added to longer term 15 °C-cultured cells producing only basal levels of E2, the synthesis of this steroid was stimulated again to the same levels previously observed, indicating that the steroid producing enzymes were still in place. Moreover, independently of the temperature or the T level in the culture medium, the maximum values of E2 production were always the same. Altogether these data suggest some sort of limit in E2 production by the primary culture other than the absence of steroid precursors. In several fish species such as rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), carp or coho salmon as well as in sea bass, it has been demonstrated that FSH, IGF-I or insulin stimulate both aromatase expression and activity (Maestro et al. 1997; Montserrat et al. 2004; Molés et al. 2008; Paul et al. 2010) in ovarian tissue fragments, isolated follicles or even isolated theca and granulosa cells. The absence of these factors controlling aromatase activity in our primary culture could be an explanation for the differences observed between T and E2 profiles after androstenedione treatment. However, further studies including hormonal treatments or measurement of aromatase activity are needed to clarify this aspect.

In functional gene and genomic studies, as well as intracellular pathway analyses, the availability of a homologous biological system is preferred. Thus, the ability to introduce and express genes in conspecific cell lines and, more, primary cultures is essential; although, traditionally, a major drawback has been the difficulty in transfecting these primary cultures. Our primary culture of follicular cells was successfully transfected both with the calcium phosphate method and Fugene reagent. The introduction of genes of interest enables the study of downstream key interactions and the transfection of promoter sequences directing expression of measurable genes allows upstream understanding of regulatory processes. Although in higher vertebrates this is an extended procedure: porcine, hen or rat granulosa cells, for example, are commonly transfected for functional studies (Carlone and Richards 1997; Sekar and Veldhuis 2001; Johnson et al. 2002), in the case of fish, to our knowledge, transient transfection of follicular cells has only been previously described for Atlantic croaker (Dressing et al. 2010). Thus, we have developed a useful homologous tool to study genes of interest for sea bass reproduction, as well as the up and downstream processes related to them.

Freezing and thawing cycles did not affect any of the studied characteristics of the follicular culture. Except for a slight mortality (4 %) the behaviour of thawed cells in terms of growth and proliferation, transfection efficiency or steroid production capability, remained similar to those of fresh prepared cultures. This fact is a huge advantage for researchers working with long reproductive cycle species, which depend on the availability of fish in the adequate stage of development for their tissue culture experiments. This is the case of the European sea bass, a seasonal spawner, in which this kind of experiments have been limited and condensed in a quite narrow window of the year. Moreover, being the high resemblance with the in vivo scenario the major advantage of a primary culture, the variability among cultures represents the main inconvenience of these in vitro systems. Here such variability could be easily reduced by storing a particular culture, thus enabling repeated experimental work with cells sharing identical characteristics. Therefore, the possibility of freezing and thawing the follicular primary cell culture without loss of the cell properties makes this in vitro system an extremely valuable tool expanding the possibilities and timing of research.

Altogether these results indicate that we have developed an in vitro homologous system for European sea bass that resembles the in vivo situation within the follicular cell layer surrounding the oocyte. This cell culture will be essential to perform both functional and gene expression studies at a cellular level in this species and evolutionary related ones.

Acknowledgments

We thank especially to Soledad Ibáñez for excellent technical assistance with steroid analysis. This work was supported by the Spanish MICINN (AGL2008-02937, Aquagenomics CSD2007-00002), the GV (ACOMP2010/083) and CSIC (PIE-I3-2006 3 01 037).

References

- Ahne W. Fish cell culture: a fibroblastic line (PG) from ovaries of juvenile pike (Esox lucius) In Vitro. 1979;15:839–840. doi: 10.1007/BF02618036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvariño JMR, Carrillo M, Zanuy S, Prat F, Mañanós E. Pattern of sea bass oocyte development after ovarian stimulation by LHRHa. J Fish Biol. 1992;41:965–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1992.tb02723.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E, Little B, Lee GS. Androgen-induced changes in rat ovarian granulosa cells in vitro. Tissue Cell. 1987;19:217–234. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(87)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E, Nijenhuis W, Male R, Swanson P, Bogerd J, Taranger GL, Schulz RW. Pharmacological characterization, localization and quantification of expression of gonadotropin receptors in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) ovaries. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;163:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asturiano JF, Sorbera LA, Ramos J, Kime DE, Carrillo M, Zanuy S. Hormonal regulation of the European sea bass reproductive cycle: an individualized female approach. J Fish Biol. 2000;56:1155–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2000.tb02131.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benninghoff AD, Thomas P. Gonadotropin regulation of testosterone production by primary cultured theca and granulosa cells of Atlantic croaker: I. Novel role of CaMKs and interactions between calcium- and adenylyl cyclase-dependent pathways. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;147:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser PR, Plumb JA. Fish cell lines: establishment of a line from ovaries of channel catfish. In Vitro. 1980;16:365–368. doi: 10.1007/BF02618357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp TA, Rahal JO, Mayo KE. Cellular localization and hormonal regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone receptor messenger RNAs in the rat ovary. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1405–1417. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-10-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlone DL, Richards JS. Functional interactions, phosphorylation, and levels of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-regulatory element binding protein and steroidogenic factor-1 mediate hormone-regulated and constitutive expression of aromatase in gonadal cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:292–304. doi: 10.1210/me.11.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo M, Zanuy S, Prat F, Cerdá J, Ramos J, Mañanós E, Bromage N. Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) In: Bromage N, Roberts R, editors. Broodstock management and egg and larval quality. Oxford: Black Science; 1995. pp. 138–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Kou G (1988) Establishment, characterization and application of 14 cell lines from warm-water fish. In: Kuroda Y, Kurstak E, Maramorosch K (eds) Invertebrate and fish tissue culture. Tokyo: Japan Sci Soc, pp 218–277

- Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SN, Chi SC, Ueno Y, Kou GH. A cell line derived from tilapia ovary. Fish Pathol. 1983;18:13–18. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.18.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crisponi L, Deiana M, Loi A, Chiappe F, Uda M, Amati P, Bisceglia L, Zelante L, Nagaraja R, Porcu S, Ristaldi MS, Marzella R, Rocchi M, Nicolino M, Lienhardt-Roussie A, Nivelon A, Verloes A, Schlessinger D, Gasparini P, Bonneau D, Cao A, Pilia G. The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:159–166. doi: 10.1038/84781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressing GE, Pang Y, Dong J, Thomas P. Progestin signaling through mPRalpha in Atlantic croaker granulosa/theca cell cocultures and its involvement in progestin inhibition of apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5916–5926. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epler P, Galas J, Stoklosowa S. Steroidogenic activity of carp ovarian follicular and interstitial cells at the pre-spawning and resting time: a tissue culture approach. Comp Biochem Physiol C: Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1997;116:167–170. doi: 10.1016/S0742-8413(96)00149-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez RD, Yoshimizu M, Kimura T, Ezura Y, Inouye K, Takami I. Characterization of three continuous cell lines from marine fish. J Aquat Anim Health. 1993;5:127–136. doi: 10.1577/1548-8667(1993)005<0127:COTCCL>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer JL, Lannan CN. Three decades of fish cell culture: a current listing of cell lines derived from fishes. Methods Cell Sci. 1994;16:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Galas J, Epler P, Stoklosowa S. Seasonal response of carp (Cyprinus carpio) ovarian cells to stimulation by various hormones as measured by steroid secretion: tissue culture approach. Endocr Regu. 1999;33:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-López A, Sánchez-Amaya MI, Tyler CR, Prat F. Mechanisms of oocyte development in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.): investigations via application of unilateral ovariectomy. Reproduction. 2011;142:243–253. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm S, Martínez-Rodríguez G, Rodríguez L, Prat F, Mylonas CC, Carrillo M, Zanuy S. Cloning, characterisation, and expression of three oestrogen receptors (ERalpha, ERbeta1 and ERbeta2) in the European sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;223:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm S, Rocha A, Miura T, Prat F, Zanuy S. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH/AMH) in the European sea bass: its gene structure, regulatory elements, and the expression of alternatively-spliced isoforms. Gene. 2007;388:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock JC, Rainey WE, Carr BR. Ovarian granulosa cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Kubo M, Chun SY, Haluska FG, Housman DE, Hsueh AJ. Wilms’ tumor protein WT1 as an ovarian transcription factor: decreases in expression during follicle development and repression of inhibin-alpha gene promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1356–1366. doi: 10.1210/me.9.10.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AL, Langer JS, Bridgham JT. Survivin as a cell cycle-related and antiapoptotic protein in granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3405–3413. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananen K, Markkula M, Rainio E, Su JGJ, Hsueh AJW, Huhtaniemi IT. Gonadal tumorigenesis in transgenic mice bearing the mouse inhibin alpha-subunit promoter simian-virus T-antigen fusion gene—characterization of ovarian-tumors and establishment of gonadotropin-responsive granulosa-cell lines. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:616–627. doi: 10.1210/me.9.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriakidou M, McAllister JM, Sugawara T, Strauss JF., III Expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in the human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4122–4128. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.11.4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppe L (2009) Quantification and localization of StAR expression in Atlantic cod ovaries. Dissertation, Universitetet i Bergen (UiB)

- Kobayashi Y, Horiguchi R, Nozu R, Nakamura M. Expression and localization of forkhead transcriptional factor 2 (Foxl2) in the gonads of protogynous wrasse, Halichoeres trimaculatus. Biol Sex Differ. 2010;1:3. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakra WS, Swaminathan TR, Joy KP. Development, characterization, conservation and storage of fish cell lines: a review. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2011;37:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10695-010-9411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannan C, Winton J, Fryer J. Fish cell lines: establishment and characterization of nine cell lines from salmonids. In Vitro. 1984;20:671–676. doi: 10.1007/BF02618871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PC, Armstrong DT. Interactions of steroids and gonadotropins in the control of steroidogenesis in the ovarian follicle. Annu Rev Physiol. 1980;42:71–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.42.030180.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren E, Roos G. Vacuolization in cultured cells induced by amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;14:267–269. doi: 10.1128/AAC.14.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestro MA, Planas JV, Moriyama S, Gutiérrez J, Planas J, Swanson P. Ovarian receptors for insulin and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and effects of IGF-I on steroid production by isolated follicular layers of the preovulatory coho salmon ovarian follicle. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1997;106:189–201. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1996.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna PR, Dyson MT, Stocco DM. Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression: present and future perspectives. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:321–333. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa S, Yan L, Swanson P. Localization of two gonadotropin receptors in the salmon gonad by in vitro ligand autoradiography. Biol Reprod. 1994;50:629–642. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molés G, Gómez A, Rocha A, Carrillo M, Zanuy S. Purification and characterization of follicle-stimulating hormone from pituitary glands of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;158:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molés G, Zanuy S, Muñoz I, Crespo B, Martínez I, Mañanós E, Gómez A. Receptor specificity and functional comparison of recombinant sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) gonadotropins (Fsh and Lh) produced in different host systems. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1171–1181. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.086470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montserrat N, González A, Méndez E, Piferrer F, Planas JV. Effects of follicle stimulating hormone on estradiol-17 beta production and P-450 aromatase (CYP19) activity and mRNA expression in brown trout vitellogenic ovarian follicles in vitro. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2004;137:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YS, Duleba AJ. Comparative studies of androgen metabolism in theca and granulosa cells of human follicles in vitro. Steroids. 1982;39:419–430. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(82)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama Y. Gonadotropin action on gametogenesis and steroidogenesis in teleost gonads. Zool Sci. 1987;4:209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto M, Matsuda M, Wang DS, Nagahama Y, Shibata N. Molecular cloning and analysis of gonadal expression of Foxl2 in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Kurokawa H, Asakawa S, Shimizu N, Tanaka M. Two distinct types of theca cells in the medaka gonad: germ cell-dependent maintenance of cyp19a1-expressing theca cells. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2652–2657. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pala I, Schartl M, Thorsteinsdóttir S, Coelho MM. Sex determination in the Squalius alburnoides complex: an initial characterization of sex cascade elements in the context of a hybrid polyploid genome. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Pramanick K, Kundu S, Kumar D, Mukherjee D. Regulation of ovarian steroidogenesis in vitro by IGF-I and insulin in common carp, Cyprinus carpio: stimulation of aromatase activity and P450arom gene expression. Mol Cell Endorinol. 2010;315:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J, Schalling M, Buckler AJ, Rogers A, Haber DA, Housman D. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene WT1 in the murine urogenital system. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1345–1356. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregel P, Bollo E, Cannizzo FT, Rampazzo A, Appino S, Biolatti B. Effect of anabolics on bovine granulosa-luteal cell primary cultures. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2007;45:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, Gómez A, Zanuy S, Cerda-Reverter JM, Carrillo M. Molecular characterization of two sea bass gonadotropin receptors: cDNA cloning, expression analysis, and functional activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;272:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha A, Zanuy S, Carrillo M, Gómez A. Seasonal changes in gonadal expression of gonadotropin receptors, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and steroidogenic enzymes in the European sea bass. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;162:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez L, Begtashi I, Zanuy S, Carrillo M. Development and validation of an enzyme immunoassay for testosterone: effects of photoperiod on plasma testosterone levels and gonadal development in male sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.) at puberty. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2000;23:141–150. doi: 10.1023/A:1007871604795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar N, Veldhuis JD. Concerted transcriptional activation of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene by insulin and luteinizing hormone in cultured porcine granulosa-luteal cells: possible convergence of protein kinase a, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2921–2928. doi: 10.1210/en.142.7.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma RK, Bhardwaj JK. In situ evaluation of granulosa cells during apoptosis in caprine ovary. Int J Integr Biol. 2009;5:58–61. doi: 10.3923/ijb.2009.58.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simione FP, Brown EM. ATCC preservation methods: freezing and freeze-drying. 2. Rockville: American Type Culture Collection; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stoklosowa S, Epler P. The endocrine activity of isolated follicular cells of the carp ovary in primary culture. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1985;58:386–393. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(85)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoklosowa S, Gregoraszczuk E, Channing CP. Estrogen and progesterone secretion by isolated cultured porcine thecal and granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 1982;26:943–952. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod26.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szoltys M, Stoklosowa S, Kasten FH. Hormonal secretion of cultured rat ovarian follicles isolated at various hours of proestrus. In Vitro. 1982;18:463–468. doi: 10.1007/BF02796474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DS, Kobayashi T, Zhou LY, Paul-Prasanth B, Ijiri S, Sakai F, Okubo K, Morohashi K, Nagahama Y. Foxl2 up-regulates aromatase gene transcription in a female-specific manner by binding to the promoter as well as interacting with ad4 binding protein/steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:712–725. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Mann JA. Poikilotherm vertebrate cell lines and viruses: a current listing for fishes. In Vitro. 1980;16:168–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02831507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]