Abstract

Background

The green anole lizard, Anolis carolinensis, is a key species for both laboratory and field-based studies of evolutionary genetics, development, neurobiology, physiology, behavior, and ecology. As the first non-avian reptilian genome sequenced, A. carolinesis is also a prime reptilian model for comparison with other vertebrate genomes. The public databases of Ensembl and NCBI have provided a first generation gene annotation of the anole genome that relies primarily on sequence conservation with related species. A second generation annotation based on tissue-specific transcriptomes would provide a valuable resource for molecular studies.

Results

Here we provide an annotation of the A. carolinensis genome based on de novo assembly of deep transcriptomes of 14 adult and embryonic tissues. This revised annotation describes 59,373 transcripts, compared to 16,533 and 18,939 currently for Ensembl and NCBI, and 22,962 predicted protein-coding genes. A key improvement in this revised annotation is coverage of untranslated region (UTR) sequences, with 79% and 59% of transcripts containing 5’ and 3’ UTRs, respectively. Gaps in genome sequence from the current A. carolinensis build (Anocar2.0) are highlighted by our identification of 16,542 unmapped transcripts, representing 6,695 orthologues, with less than 70% genomic coverage.

Conclusions

Incorporation of tissue-specific transcriptome sequence into the A. carolinensis genome annotation has markedly improved its utility for comparative and functional studies. Increased UTR coverage allows for more accurate predicted protein sequence and regulatory analysis. This revised annotation also provides an atlas of gene expression specific to adult and embryonic tissues.

Keywords: Annotation, Lizard, Anolis carolinensis, Transcriptome, Genome, RNA-Seq, Gene, Vertebrate, Embryo, Tissue-specific

Background

Recent advances in sequencing technologies and de novo genome assembly algorithms have greatly reduced the time, cost, and difficulty of generating novel genomes [1]. This has led to organized efforts to sequence a representative species from all major vertebrate taxa, referred to as the Genome 10K Project [2], as well as a similar project to sequence five thousand insect genomes, the i5K project [3]. While these efforts have the potential to transform comparative studies, many applications including studies of biological function will be limited without quality genome annotations. Genome annotations of newly sequenced species initially rely primarily on ab initio gene predictions and alignment of reference transcripts of related species; however, the quality of gene models is greatly improved when incorporating same species transcriptomic sequencing [4]. In particular, information from high-density next-generation RNA sequencing, i.e., deep transcriptomes, greatly improves even well-annotated genomes [5].

While 39 mammalian genomes and 3 avian genomes have been published [6], whole genome sequences have only recently been available for non-avian reptiles. The first published non-avian reptilian genome was that of a squamate, the lizard Anolis carolinensis (Anocar2.0 assembly) [7]. Subsequently, releases of draft genomes from another squamate, the Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus, [8] and three crocodilian species: the American alligator, Alligator mississippiensis, the gharial Gavialis gangeticus, and the saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus[9] were published. As an emerging model system with its genome sequence available, the green anole has already proved useful in a variety of fields including comparative genomics [10-13], functional genomics [14,15], behavior [16,17], evolutionary genetics [18,19], and development and evolution [20,21]. In all of these areas of research, the green anole genome, in combination with avian and mammalian data, provides a key perspective on conserved and divergent features among amniotes.

Currently, the public databases of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Ensembl, and University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) have devoted anole genome portals. NCBI and Ensembl provide first generation genome annotations, which are based primarily on conservation with other species [7]. These first generation annotations rely heavily on conservation of protein-coding sequences, and as such, predicted green anole genes generally lack untranslated regions (UTRs) and often do not contain start and/or stop codons. Furthermore, alternative splice forms and evolutionarily divergent orthologues are not represented in the first generation annotations. These issues have limited the ability of researchers to carry out comparative and functional genomic studies based on the A. carolinensis genome sequence.

In order to help resolve many of these issues, here we present a second generation revised annotation based on a foundation of 14 de novo deep transcriptomes and published cDNA sequences. We used a customized pipeline based on the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA) [5,22-24], EVidenceModeler (EVM) [4] and MAKER2 [25,26] to combine the following data: i) de novo and reference based assemblies of 14 RNA-Seq transcriptomes, ii) 7 publicly available EST libraries, iii) RefSeq alignments of the available vertebrate transcripts, iv) RefSeq alignments of zebrafish, Xenopus frog, chicken, mouse, and human protein sequences, v) NCBI and Ensembl current annotations, and vi) ab initio gene predictions based on analysis by SNAP and Augustus [27-29].

Results and discussion

De novo transcriptome generation and assembly

We carried out RNA-Seq to generate 11 adult tissue and 3 embryonic transcriptomes (Table 1). Strand-specific directional sequences were generated from adrenal gland, brain, dewlap skin, heart, liver, lung, ovary, and skeletal muscle. RNA-Seq generated by directional library construction can be used to distinguish between coding transcripts and antisense noncoding transcripts. The adrenal, lung, liver and skeletal muscle samples were derived from a single male individual (Additional file 1: Table S1). The brain, dewlap skin, heart, and ovary samples were pooled from several individuals (Additional file 1: Table S1). Standard non-directional RNA-Seq libraries were prepared from regenerating tail and embryonic tissues. Lizards including the green anole can regenerate their tail following autotomy, or self-amputation [30]. Regenerating tissues from 3 tails at 15 days post-autotomy were divided into pools of the regenerating epithelial tip and the adjacent tail base. RNA-Seq was also performed on the original autotomized tail from those same animals. Embryos between zero to one day after egg laying (28 and 38 somite-pair stages) were analyzed individually by standard RNA-Seq as well as pooled for directional library construction and sequencing. More than 762 million paired-end reads were generated from these adult and embryonic tissue samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of de novo transcript assembly for A. carolinensis based on RNA-Seq data from 14 adult and embryonic tissues and deposited EST sequence data

| De novo RNA-Seq | # Reads | De novo assembled transcripts | Transcripts aligning to Anocar2.0 assembly | PASA assembled transcripts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embryo-28 somite stage |

52,548,024 |

83,627 |

81,032 |

22,670 |

| Embryo-38 somite stage |

55,048,179 |

99,578 |

95,753 |

24,595 |

| Regenerating tail tip |

122,099,352 |

92,275 |

88,150 |

22,278 |

| Regenerating tail base |

31,721,054 |

78,005 |

73,516 |

24,897 |

| Original tail |

109,404,060 |

96,450 |

91,601 |

20,240 |

| Adrenal |

55,858,836 |

110,349 |

101,449 |

20,482 |

| Brain |

32,518,977 |

203,519 |

192,407 |

33,912 |

| Dewlap skin |

31,785,178 |

81,598 |

76,866 |

25,853 |

| Embryos (pooled) |

59,681,427 |

118,949 |

110,124 |

19,969 |

| Heart |

34,068,834 |

154,255 |

144,617 |

26,582 |

| Liver |

50,782,350 |

89,010 |

81,441 |

21,549 |

| Lung |

48,723,049 |

272,071 |

255,035 |

37,985 |

| Ovary |

35,139,647 |

80,306 |

75,807 |

26,827 |

| Skeletal Muscle |

42,707,477 |

75,006 |

69,250 |

18,857 |

|

Total |

762,086,444 |

1,634,998 |

1,537,048 |

346,696 |

|

EST Library (NCBI) |

# Sequences |

NCBI defined UniGene groups |

Transcripts aligning to Anocar2.0 assembly |

PASA assembled transcripts |

| Brain |

19,139 |

5,631 |

9,991 |

1,715 |

| Dewlap skin |

19,809 |

5,453 |

10,180 |

2,216 |

| Embryo |

38,923 |

8,714 |

9,991 |

4,158 |

| Mixed Organ |

19,863 |

5,657 |

9,327 |

2,053 |

| Ovary |

19,410 |

5,467 |

7,394 |

3,737 |

| Regenerating Tail |

19,851 |

6,751 |

11,064 |

6,757 |

| Testis |

19,807 |

4,261 |

8,677 |

2,594 |

| Total | 156,802 | 41,934 | 66,624 | 23,230 |

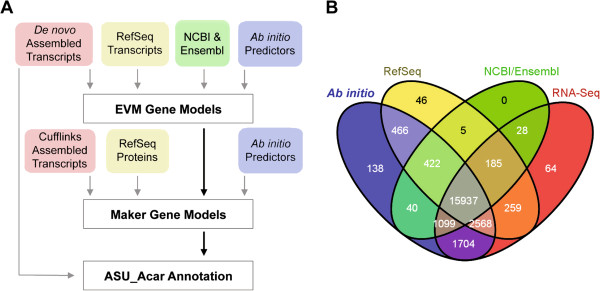

The pipeline for de novo assembly of RNA-Seq data involved two steps. First, strand-specific transcriptome sequence libraries were assembled using Trinity (Figure 1A) [31]. Standard non-directional RNA-Seq libraries were assembled using ABySS and Trans-ABySS [32-34]. In total, this generated more than 1.62 million de novo assembled transcript contigs. Second, these assembled contigs were aligned to the A. carolinensis Anocar2.0 assembly [7] using the gmap tool within PASA, with the aim of i) eliminating sequences not aligning to the genome and ii) merging de novo assembled sequences to remove redundancy. We observed that over 94% of these sequences aligned to the green anole genome at a cutoff of 95% identity and 90% transcript coverage. This first step of the de novo assembly pipeline reduced the number of RNA-Seq based transcript contigs down to 669,584.

Figure 1.

A. Diagram of the bioinformatic pipeline for the A. carolinensis reannotation. B. Venn diagram illustrating the sources of data for the A. carolinensis reannotation. Ab initio, algorithm based gene predictions using Augustus and SNAP [26-28]. RefSeq, alignments of zebrafish, Xenopus frog, chicken, mouse, and human protein and available vertebrate transcripts to the Anocar2.0 genome assembly. NCBI/Ensembl, combined data of A. carolinensis genome annotations from NCBI ref_Anocar2.0 and Ensembl Build 65. RNA-Seq, transcriptomic data from analysis of 14 adult and embryonic tissues.

As part of the A. carolinensis genome sequencing effort, EST sequences were generated from five adult organs (brain, dewlap skin, ovary, regenerated tail, and testis), embryo, and a seventh mixed organ library that included heart, kidney, liver, lung, and tongue [7]. These EST sequences were introduced at the second step of this pipeline and aligned to the A. carolinensis Anocar2.0 assembly using gmap, identifying another 35,188 transcript contigs not present from the RNA-Seq deep transcriptomic data. This yielded a total of 704,772 transcript contigs that were then used as the basis of the second generation A. carolinensis genome annotation (Table 1).

Generating a revised annotation of the A. carolinensis genome

The reannotation of the A. carolinensis genome incorporates four classes of evidence that were combined using the EVM tool (Figure 1A) [4]. First, the 704,772 de novo assembled transcript contigs were given the highest weight to generate the revised annotation. Second, two ab initio gene prediction tools, SNAP and Augustus [27-29], were trained using a subset of the PASA transcriptome assemblies after removing redundancy using CD-HIT [35]. In brief, 9,064 A. carolinensis coding sequences were used to train SNAP, and 1,041 complete predicted protein sequences were used to train Augustus. Third, the first generation A. carolinensis gene annotations from NCBI ref_Anocar2.0 (abbreviated as NCBI) and Ensembl Build 65 (abbreviated as Ensembl) were used as an input to EVM. Finally, regions of alignment to RefSeq homologous transcript sequences from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics portal were also incorporated into the EVM predictions.

Since EVM currently generates only a single protein-coding sequence for each gene and the transcript evidence requires at least 90% alignment to the genome, further steps were necessary to improve the annotation. First, the RNA-Seq reads were aligned to the Anocar2.0 assembly using TopHat and reference guided assemblies were completed using Cufflinks. Second, the EVM predictions, the Cufflinks assemblies, as well as zebrafish, Xenopus frog, chicken, mouse, and human protein alignments, were used as input into MAKER2 to annotate novel genes, extend UTR sequence, and annotate alternative splicing (Figure 1A). These models were updated to further incorporate UTR sequences and alternate splice forms present in the de novo assembled transcripts described above. We have named this second generation annotation for A. carolinensis ASU_Acar version 2.1 (abbreviated as ASU).

Sources for genome reannotation

The improvements in the ASU annotation derive from multiple sources. The largest group of annotated genes, 69% or 15,937, were based on all sources of data, and an additional 30% (6,776) were based on two or three sources of data (Figure 1B). In addition, RNA-Seq was a key source of data for this reannotation, contributing to 95% of all gene predictions. Only 1% of predicted genes were based solely on one source of data (transcriptome, NCBI or Ensembl annotation, RefSeq alignment, or ab initio predictions). The ab initio gene predictions, which do not make use of any empirically derived data, contribute less than 1% (138) of the gene predictions for this reannotation. Since both the first and second generation annotation pipelines rely on open reading frame and coding sequence predictions, noncoding transcripts are likely underrepresented. The generation of long noncoding and microRNA-Seq data and sampling of more tissues by the research community will contribute to improved A. carolinensis genome annotations in the future.

Improvements in gene annotation

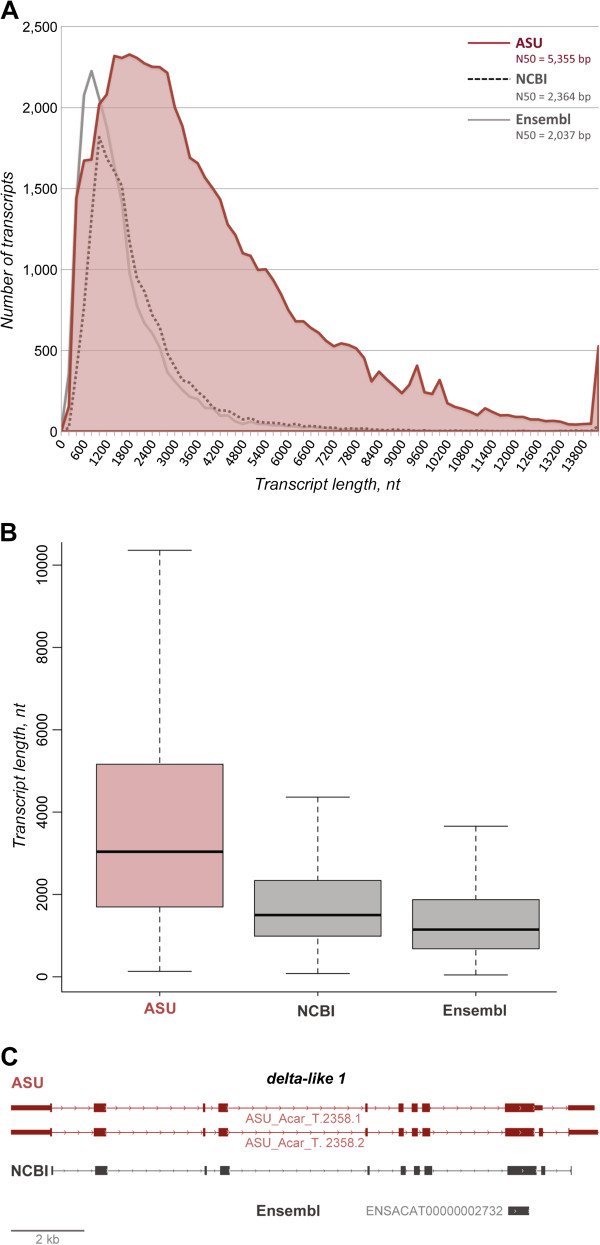

To quantify the differences between the first and second generation genome annotations, we compared ASU with the NCBI and Ensembl annotations. First, the ASU annotation has identified more genes than either NCBI or Ensembl (22,962 vs. 15,645 in NCBI and 17,792 in Ensembl; Table 2). Second, the ASU annotation greatly increases the number of annotated transcript isoforms (59,373 vs. 16,533 for NCBI and 18,939 for Ensembl; Table 2). Third, predicted transcripts in the ASU annotation appear to be more complete in a number of different parameters. Of the 59,373 annotated transcript isoforms, 90% (53,401) are predicted to be complete protein-coding sequences. Furthermore, 59% (34,926) are predicted to contain 3’ UTR sequences, and 79% (46,782) to contain 5’ UTR sequences (Table 2). In addition, the ASU annotation greatly improves transcript lengths (5,355 bp vs. 2,364 bp for NCBI and 2,037 bp for Ensembl; Figure 2A & B; Table 2). An example of the improvements in gene annotation is evident the Notch pathway ligand, delta-like 1 (Figure 2C; gene symbol dll1 following guidelines of the Anolis Gene Nomenclature Committee) [36].

Table 2.

Comparison of ASU, NCBI and Ensembl gene annotations of the A. carolinensis genome

| Overview | ASU | NCBI | Ensembl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annotated genes |

22,962 |

15,645 |

17,792 |

| Annotated transcript isoforms |

59,373 |

16,533 |

18,939 |

| Annotated isoforms/gene |

2.59 |

1.06 |

1.06 |

|

Annotated Transcripts | |||

| All transcript isoforms |

59,373 |

16,533 |

18,939 |

| Transcripts with start & stop codons |

53,401 |

14,667 |

4,170 |

| Transcripts missing start or stop codon |

5,972 |

1,866 |

14,769 |

| Single exon transcripts |

2,070 |

983 |

364 |

| Transcript N50 length |

5,355 |

2,364 |

2,037 |

| Average coding sequence length |

1,964 |

1,701 |

1,531 |

|

Exons | |||

| Total number of exons |

229,204 |

156,742 |

174,545 |

| Exons with start with codon |

29,677 |

13,512 |

5,971 |

| Exons without start or stop codon |

168,367 |

128,486 |

158,935 |

| Exons with stop codon |

29,727 |

13,779 |

9,278 |

| Exons/annotated transcript |

12.05 |

10.11 |

9.62 |

| Average exon length |

170 |

170 |

160 |

| Total exon length |

38,902,806 |

26,658,387 |

27,910,718 |

|

3' UTR | |||

| Total transcripts with 3'UTR |

34,926 |

5,861 |

0 |

| Average length of transcripts with 3'UTR |

1,168 |

456 |

0 |

| Total 3'UTR sequence length |

40,798,794 |

2,674,388 |

0 |

|

5' UTR | |||

| Total transcripts with 5'UTR |

46,782 |

6,168 |

0 |

| Average length of transcripts with 5'UTR |

244 |

86 |

0 |

| Total 5'UTR sequence length |

11,422,626 |

527,454 |

0 |

|

Introns | |||

| Total number of introns |

192,418 |

141,362 |

155,949 |

| Average intron length |

4,525 |

4,463 |

2,553 |

| Total intron sequence length | 870,771,088 | 630,937,171 | 398,124,572 |

Figure 2.

Increased N50 transcript length and number of predicted transcripts in the ASU annotation.A. The distribution of transcript lengths is shown for the ASU, NCBI and Ensembl genome annotations. The ASU annotation transcript N50 length of 5,355 bp is greater than values for the first generation annotations from Ensembl (2,037 bp) and NCBI (2,364 bp). B. A boxal plot showing the median (horizontal line) and boundaries for the 25th and 75th percentiles (box) as well as the range for the ASU, NCBI, and Ensembl predicted transcripts. C. The Notch ligand dll1 is an example of gene whose annotation has been markedly improved in the ASU annotation.

Assignment of gene orthology

Identification of orthologous relationships between genes in A. carolinensis and other vertebrate model systems is a key step in comparative studies. However, this is a complex task due to gene deletions and genome duplications and rearrangements during vertebrate evolution. For protein-coding genes, metrics have been proposed [36] that consider both protein sequence similarity and synteny conservation. For comparison of ASU annotation, we have used the current orthology assignments in the NCBI and Ensembl gene models. Given the longer transcript lengths in the ASU annotation we identified that 16,303 genes overlapped with Ensembl predicted genes and 16,908 overlapped with NCBI predicted genes (Additional file 2: Table S2).

However, this comparison left 5,246 ASU predicted genes with no orthology assignment based on NCBI or Ensembl annotations. Gene orthology for these remaining predicted genes were next evaluated by Blast2GO against the vertebrate RefSeq database [37-39]. This analysis demonstrated that 56% of these predicted genes (2,928/5,246) had a Blast2GO Expect (E) value score of at least 10-3 with a vertebrate gene, which is suggestive of a potential orthologue (Table 3; Additional file 3: Table S3). Of these predicted genes, 90% (2,627/2,928) contain multiple exons with an average of 6.4 exons/gene and a N50 value of 2,157 bp. These may reflect genes that have been newly identified in the ASU annotation but were missing in the NCBI and Ensembl annotations. The remaining 10% of the predicted genes (301/2,928) contain only a single annotated exon, which could result from gaps in the Anocar2.0 reference genome assembly. The remaining group of genes (2,318/5,246) aligned to the Anocar2.0 assembly but had poor vertebrate homology. This group may include novel lizard genes and rapidly diverging genes such as noncoding RNAs.

Table 3.

A. carolinensis genes that are unique to the ASU annotation and have vertebrate orthologues

| Gene | ASU |

|---|---|

| Annotated genes |

2,928 |

| Annotated transcript isoforms |

3,612 |

| Annotated isoforms/gene |

1.23 |

|

Transcript | |

| All transcript isoforms |

3,612 |

| Transcripts with start & stop codons |

2,698 |

| Transcripts missing start or stop codon |

914 |

| Single exon transcripts |

301 |

| Transcript N50 length |

2,157 |

| Average coding sequence length |

1,182 |

|

Exon | |

| Total number of exons |

18,921 |

| Exons with start with codon |

2,468 |

| Exons without start or stop codon |

13,901 |

| Exons with stop codon |

2,300 |

| Exons/annotated transcript |

6.35 |

| Average exon length |

188 |

| Total exon length |

3,569,265 |

|

3' UTR | |

| Total transcripts with 3'UTR |

1,323 |

| Average length of transcripts with 3'UTR |

761.2 |

| Total 3'UTR sequence length |

1,007,040 |

|

5' UTR | |

| Total transcripts with 5'UTR |

1,816 |

| Average length of transcripts with 5'UTR |

238.7 |

| Total 5'UTR sequence length |

433,533 |

|

Intron | |

| Total number of introns |

15,835 |

| Average intron length |

5,304 |

| Total intron sequence length | 83,999,254 |

Transcripts with vertebrate homology not present in the Anocar2.0 genome assembly

Given a 7.1x genome coverage for the A. carolinensis Anocar2.0 assembly, only 81% of the 2.2 Gbp genome is predicted to be included in the current contig sequences [7]. In addition, approximately 30% of the A. carolinensis genome consists of repetitive mobile element sequences, which leads to a lower than typical N50 given the sequencing depth. Thus, some transcripts identified by RNA-Seq analysis would not align to the Anocar2.0 assembly, and these transcripts would not included in the ASU annotation. This category of genes missing from the Anocar2.0 assembly may include important developmental or regulatory genes.

We developed a pipeline to analyze the genes poorly represented in the Anocar2.0 assembly (see Materials and Methods). Starting with 638,802 de novo assembled contigs, the pipeline reduced this group down to 29,706 and increased the N50 value from 349 bp up to 2,074 bp. Next, these 29,706 contigs were analyzed by Blast2GO to identify homology to vertebrate RefSeq entries with an E-value cutoff of 10-3 (Additional file 3: Table S3). The majority of these contigs (56% or 16,542/29,706) could be matched to 6,695 distinct vertebrate orthologues (Additional file 4: Table S4; Additional file 5: Figure S1).

Analyzing these matching contigs further, we were able to identify matches with 30% of the contigs (4,910/16,542) against the 2,233 A. carolinensis RefSeq proteins. This suggests that these transcript contigs that matched A. carolinensis RefSeq proteins but failed to align to the Anocar2.0 assembly contain genes that are partially represented on the genome or are interrupted by large gaps in the scaffolds. The remaining 70% (11,632/16,542) of these contigs mapped with highest scores to other vertebrate species (Additional file 5: Figure S1). This is likely due to the incomplete state of the A. carolinensis RefSeq libraries. Genes missing from A. carolinensis annotations can be attributed to gaps in the Anocar2.0 assembly; misassembly in genome scaffolds would interrupt contiguous alignments of transcripts at contig sequence boundaries. Given these observations, additional sequencing to increase coverage of the A. carolinensis genome would improve future annotations.

High quality genome annotation requires both whole genome and transcriptome sequencing

Next-gen sequencing technologies are accelerating the rate at which whole genome assemblies are being completed. Among the non-avian reptiles, genomes drafts have been reported for the snake P. m. bivittatus, [8], and the crocodilian reptiles A. mississippiensis, G. gangeticus, and C. porosus[9]. However, the reannotation of the A. carolinensis genome has highlighted the relevance of collecting deep transcriptome data from a diverse array of tissues. For evolutionary genetic studies, maximizing the coverage of protein coding sequences is essential, and prediction of these regions based on whole genome sequences alone is challenging. Furthermore, identification of cis-regulatory regions is aided by improved gene annotations, since the 5’ untranslated sequences near the promoter are poorly conserved compared to protein coding sequences. Alternate splicing is a mechanism that greatly increases the diversity of transcripts from vertebrate genomes, but identification of isoforms requires transcript sequence data from a variety of tissues. Reannotation of the anole genome suggests that for the Genome 10K Project [2], it will be necessary to carry out both whole genome and transcriptome sequencing efforts in order to achieve the comparative genomic goals.

Conclusions

With the release of the A. carolinensis genome, along with a first generation annotation provided by NCBI and Ensembl, a growing foundation of genomic resources are available for the anole reptilian model. Furthermore, genome annotations of this key reptilian model provide a valuable resource for genomic comparison with mammals, such as mice and humans. Using RNA-Seq, we have improved the genome annotation for A. carolinensis, which includes 59,373 transcript isoforms, many of which are complete with UTR sequences. De novo transcriptome assembly also identified 16,542 transcripts that are not well represented on the current Anocar2.0 genome build. This revised genome annotation and available transcriptomic sequences provide a resource for vertebrate comparative and functional studies. This work also highlights the need for additional genomic sequencing of A. carolinensis to fill in gaps and extend scaffolds, as well as further transcriptomic sequencing of additional tissues.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animals were maintained and research carried out according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of Arizona State University. Anolis carolinensis lizards were purchased from approved vendors (Charles D. Sullivan Co., Inc., Nashville, TN; Marcus Cantos Reptiles, Fort Myers, FL) and were housed at 70% humidity. Lighting and temperature were maintained for 14 hours at 28°C daylight and 10 hours at 22°C night. Adult tissues were collected immediately after euthanasia. Eggs were collected within one day of laying, typically at the 25-30 somite pair stage.

RNA-Seq

Samples for RNA-Seq, including embryos, regenerating tail, original tail, dewlap skin, brain, heart, lung, liver, adrenal, ovary, and skeletal muscle were collected for extraction using the total RNA protocol of the miRVana kit (Ambion). For the regenerating tail, original tail, 28 and 38 somite-pair staged embryos, total RNA samples were prepared using the Ovation RNA-Seq kit (NuGEN) to generate double stranded cDNA. Illumina manufacturer protocols were followed to generate paired-end sequencing libraries. Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 using paired-end chemistry with read lengths of 104 base pairs. Strand-specific RNA sequencing libraries were prepared for adrenal, brain, dewlap, pooled 28 and 38 somite staged embryos, heart, liver, lung, skeletal muscle, and ovary RNA samples using the dUTP protocol [40]. The dUTP strand-specific libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq using paired-end chemistry with read lengths of either 76 or 101 bp.

De novo assembly

Non-directional RNA-Seq data was assembled using the ABySS and Trans-ABySS pipeline [31-33]. Each sample was assembled in ABySS using every 5th kmer ranging from 26bp to 96bp. These assemblies were then combined using trans-ABySS to create a merged assembly with reduced redundancy. This merged assembly was then mapped to the genome using BLAT inside trans-ABySS. De novo assembled contigs were then filtered to require at least 90% coverage of the contig to the genome and at least one 25 bp gap. Because of its ability to utilize stranded information, Trinity was used to assemble the strand-specific RNA sequencing data using default parameters [30].

PASA alignment assembly

The de novo assembled transcripts from ABySS/Trans-ABySS and Trinity [31], as well as the contigs from the EST data sets, were then assembled using the PASA reference genome guided assembly. Seqclean was first used to remove Illumina adapters and any contaminants listed in the UniVec databases from the de novo assembled transcripts and the EST libraries. PASA alignment and assembly was then executed using default parameters and utilizing the strand-specific data when possible [5,22-24].

Ab initio training (PASA/CD-HIT) and prediction

In order to train ab initio gene prediction algorithms, a set of high confidence transcripts were extracted from the PASA assemblies from each RNA sequencing data set. These transcripts were then combined and redundancy removed using CD-HIT [35,40]. This set of transcripts was then used to train gene identification parameters for Augustus [28,29], as well as SNAP [27] inside MAKER2 [25,26]. Each gene finder was then run to produce a set of ab initio predictions for the A. carolinensis genome.

EVM annotation combiner/PASA updates

EVidenceModeler [4] was utilized to combine ab initio gene predictions from Augustus and SNAP, the Ensembl Build 65, and the NCBI ref_Anocar2.0 gene predictions, in combination with UCSC reference protein alignments and A. carolinensis transcriptomic data from the PASA assembles. This initial annotation ignored alternate splicing and UTRs. Cufflinks assemblies derived from TopHat alignments of the raw reads, as well as human and chicken RefSeq protein alignments carried out using Exonerate, were used to guide a MAKER2 annotation update to include novel genes, UTR sequences and alternative splicing isoforms [41-48]. PASA was then again utilized to update this initial genome annotation from EVM and MAKER2 to add alternate splicing and UTR sequences based on transcript data [4,5,22-24,26]. Orthologues were then assigned to these annotations through finding overlapping gene annotations from NCBI or Ensembl gene models. ASU gene predictions that did not have an overlap with NCBI or Ensembl genes were then assigned orthology by identifying the most similar vertebrate RefSeq protein using blastx inside Blast2GO [37-39].

Reference guided assembly

To improve the annotations of genes located in regions interrupted by gaps in the genomic assembly, sequencing reads were used for reference guided transcript assembly. Reads from each sample were first trimmed based on quality and mapped to the A. carolinensis genome using Bowtie and TopHat as described previously [42,44,45]. Read alignments and the EVM gene models were then used to guide a Reference Annotation Based Transcript (RABT) assembly using Cufflinks version 2.0.0 [43,46,48].

Analysis of transcript contigs that failed to align to the Anocar2.0 genome assembly

All tissue-specific contigs that failed to align to the Anocar2.0 genome assembly were processed and assembled using CAP3 [49]. This second assembly step reduces redundancy between the assemblies from each sample and extends any partial transcripts contained within individual sample assemblies. Transcripts were filtered to remove >33% percentage of repetitive sequences using RepeatMasker [50] and remaining transcripts that contained open reading frames longer than 100 amino acids were then extracted from the CAP3 assembly for further analysis. Because CAP3 tended to reconstruct more complete transcripts, these transcripts containing ORFs longer than 100 amino acids were then realigned to the genome using BLAT and alignments covering greater than 70% of the transcript at 90% identity were removed [51]. The filtered transcript contigs were then assigned orthology based on a best blastx match to vertebrate RefSeq proteins using Blast2GO [37-39].

Annotation files and accession numbers

The ASU_Acar version 2.1 annotation files have been deposited to NCBI and Ensembl for release through their anole-specific portals. Assemblies and the meta-assembly of unmapped transcripts have also been distributed to the A. carolinensis community research portals, AnolisGenome (http://www.anolisgenome.org) and lizardbase (http://www.lizardbase.org).

Accession numbers for non strand-specific RNA-Seq and transcript assemblies: embryo-28 somite [NCBI-GEO: GSM848765; SRA: SRX111311, TSA: SUB139328], embryo-38 somite [NCBI-GEO: GMS848766, SRA: SRX111310, TSA: SUB139329], regenerating epithelial tail tip [SRA: SRX158076, TSA: SUB139331], regenerating tail base [SRA: SRX158077, TSA: SUB139332], tail [SRA: SRX158074, TSA: SUB139330]. Accession numbers for strand-specific RNA-Seq and transcript assemblies: adrenal gland [SRA: SRX145078, SRX146889, TSA: SUB139081], brain [SRA: SRX111454, TSA: SUB139082], dewlap skin [SRA: SRX111451, TSA: SUB139084], embryo pooled [SRA: SRX115247, SRX146888, TSA: SUB139085], heart [SRA: SRX111452, TSA: SUB139086], liver [SRA: SRX112551, TSA: SUB139087], lung [SRA: SRX112552, TSA: SUB139088], ovary [SRA: SRX111453, TSA: SUB139091], skeletal muscle [SRA: SRX112550, TSA: SUB139090], the reassembly of unmapped transcripts from all RNA-seq data [TSA: SUB139333]. Library accession numbers for EST sequence libraries reported previously [7] used for analysis: brain [UniGene: Lib.23338], dewlap skin [UniGene: Lib.23339], embryo [UniGene: Lib.23340], mixed organ [UniGene: Lib.23341], ovary [UniGene: Lib.23342], regenerating tail [UniGene: Lib.23343], testis [UniGene: Lib.23344].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

WE, EH and KK planned the experiments. WE, EH, GM, and KK managed the lizard colony, collected tissue samples and extracted RNA. AA, JC, EH, and MH carried out the nondirectional RNA-Seq. FdP, KL-T and JA supervised the directional RNA-Seq efforts. WE, EH, and KK wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Description of adult and embryonic tissues used for RNA-Seq.

Table S2. Orthology assignment of ASU_Acar genes.

Table S3. Orthology assignment of unmatched ASU_Acar annotated genes by Blast2GO.

Table S4. Orthology assignment of unmapped transcripts by Blast2GO.

Figure S1. Blast2GO matches for transcripts poorly aligning to the Anocar2.0 genome assembly. The species with the highest Blast2GO matches are shown.

Contributor Information

Walter L Eckalbar, Email: weckalba@asu.edu.

Elizabeth D Hutchins, Email: edhutchi@asu.edu.

Glenn J Markov, Email: glenn.markov@stanford.edu.

April N Allen, Email: aallen@tgen.org.

Jason J Corneveaux, Email: jcorneveaux@tgen.org.

Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, Email: kersli@broad.mit.edu.

Federica Di Palma, Email: fdipalma@broadinstitute.org.

Jessica Alföldi, Email: jalfoldi@broadinstitute.org.

Matthew J Huentelman, Email: mhuentelman@tgen.org.

Kenro Kusumi, Email: kenro.kusumi@asu.edu.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants to K.K. (R21 RR031305 from the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the National Institutes of Health; 1113 from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission). This research was also supported by computational allocation from the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) and the Arizona State University Advanced Computing Center (A2C2). Sequencing of strand-specific libraries was funded by NHGRI. We would like to thank the Broad Institute Genomics Platform for sequencing the strand-specific libraries. The authors would like to thank Dale DeNardo, Rebecca Fisher, Joshua Gibson, Tonia Hsieh, Rob Kulathinal, Alan Rawls, and Jeanne Wilson-Rawls for reviewing this manuscript.

References

- Mardis ER. A decade’s perspective on DNA sequencing technology. Nature. 2011;470:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nature09796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genome 10K Community of Scientists. Genome 10K: A Proposal to Obtain Whole-Genome Sequence for 10 000 Vertebrate Species. J Hered. 2009;100:659–674. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GE, Hackett KJ, Purcell-Miramontes M, Brown SJ, Evans JD, Goldsmith MR, Lawson D, Okamuro J, Robertson HM, Schneider DJ. Creating a Buzz About Insect Genomes. Science. 2011;331:1386–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6023.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, White O, Buell CR, Wortman JR. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind N, Chen Z, Yassour M, Thompson DA, Haas BJ, Habib N, Wapinski I, Roy S, Lin MF, Heiman DI, Young SK, Furuya K, Guo Y, Pidoux A, Chen HM, Robbertse B, Goldberg JM, Aoki K, Bayne EH, Berlin AM, Desjardins CA, Dobbs E, Dukaj L, Fan L, FitzGerald MG, French C, Gujja S, Hansen K, Keifenheim D, Levin JZ, Mosher RA, Muller CA, Pfiffner J, Priest M, Russ C, Smialowska A, Swoboda P, Sykes SM, Vaughn M, Vengrova S, Yoder R, Zeng Q, Allshire R, Baulcombe D, Birren BW, Brown W, Ekwall K, Kellis M, Leatherwood J, Levin H, Margalit H, Martienssen R, Nieduszynski CA, Spatafora JW, Friedman N, Dalgaard JZ, Baumann P, Niki H, Regev A, Nusbaum C. Comparative Functional Genomics of the Fission Yeasts. Science. 2011;332:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1203357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, Fairley S, Fitzgerald S, Gil L, Gordon L, Hendrix M, Hourlier T, Johnson N, Kahari AK, Keefe D, Keenan S, Kinsella R, Komorowska M, Koscielny G, Kulesha E, Larsson P, Longden I, McLaren W, Muffato M, Overduin B, Pignatelli M, Pritchard B, Riat HS, Ritchie GRS, Ruffier M, Schuster M, Sobral D, Tang YA, Taylor K, Trevanion S, Vandrovcova J, White S, Wilson M, Wilder SP, Aken BL, Birney E, Cunningham F, Dunham I, Durbin R, Fernandez-Suarez XM, Harrow J, Herrero J, Hubbard TJP, Parker A, Proctor G, Spudich G, Vogel J, Yates A, Zadissa A, Searle SMJ. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:D84–D90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alföldi J, di Palma F, Grabherr M, Williams C, Kong L, Mauceli E, Russell P, Lowe CB, Glor RE, Jaffe JD, Ray DA, Boissinot S, Shedlock AM, Botka C, Castoe TA, Colbourne JK, Fujita MK, Moreno RG, Hallers ten BF, Haussler D, Heger A, Heiman D, Janes DE, Johnson J, de Jong PJ, Koriabine MY, Lara M, Novick PA, Organ CL, Peach SE, Poe S, Pollock DD, de Queiroz K, Sanger T, Searle S, Smith JD, Smith Z, Swofford R, Turner-Maier J, Wade J, Young S, Zadissa A, Edwards SV, Glenn TC, Schneider CJ, Losos JB, Lander ES, Breen M, Ponting CP, Lindblad-Toh K. The genome of the green anole lizard and a comparative analysis with birds and mammals. Nature. 2011;477:587–591. doi: 10.1038/nature10390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoe TA, de Koning JAP, Hall KT, Yokoyama KD, Gu W, Smith EN, Feschotte C, Uetz P, Ray DA, Dobry J, Bogden R, Mackessy SP, Bronikowski AM, Warren WC, Secor SM, Pollock DD. Sequencing the genome of the Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus) as a model for studying extreme adaptations in snakes. Genome Biol. 2011;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John JA, Braun EL, Isberg SR, Miles LG, Chong AY, Gongora J, Dalzell P, Moran C, Bed'hom B, Abzhanov A, Burgess SC, Cooksey AM, Castoe TA, Crawford NG, Densmore LD, Drew JC, Edwards SV, Faircloth BC, Fujita MK, Greenwold MJ, Hoffmann FG, Howard JM, Iguchi T, Janes DE, Khan SY, Kohno S, de Koning AJ, Lance SL, McCarthy FM, McCormack JE, Merchant ME, Peterson DG, Pollock DD, Pourmand N, Raney BJ, Roessler KA, Sanford JR, Sawyer RH, Schmidt CJ, Triplett EW, Tuberville TD, Venegas-Anaya M, Howard JT, Jarvis ED, Guillette LJ Jr, Glenn TC, Green RE, Ray DA. Sequencing three crocodilian genomes to illuminate the evolution of archosaurs and amniotes. Genome Biol. 2012;13:415. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-1-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollis M, Boissinot S. The transposable element profile of the Anolis genome: How a lizard can provide insights into the evolution of vertebrate genome size and structure. Mobile genetic elements. 2011;1:107–111. doi: 10.4161/mge.1.2.17733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick PA, Smith JD, Floumanhaft M, Ray DA, Boissinot S. The Evolution and Diversity of DNA Transposons in the Genome of the Lizard Anolis carolinensis. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:1–14. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes DE, Chapus C, Gondo Y, Clayton DF, Sinha S, Blatti CA, Organ CL, Fujita MK, Balakrishnan CN, Edwards SV. Reptiles and Mammals Have Differentially Retained Long Conserved Noncoding Sequences from the Amniote Ancestor. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:102–113. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita MK, Edwards SV, Ponting CP. The Anolis Lizard Genome: An Amniote Genome without Isochores. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:974–984. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassa CJ, Kulathinal RJ. Elevated Evolutionary Rates among Functionally Diverged Reproductive Genes across Deep Vertebrate Lineages. International journal of evolutionary biology. 2011;2011:1–9. doi: 10.4061/2011/274975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CH, Hamazaki T, Braun EL, Wade J, Terada N. Evolutionary genomics implies a specific function of Ant4 in mammalian and anole lizard male germ cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Cohen RE, Vandecar JR, Wade J. Relationships among reproductive morphology, behavior, and testosterone in a natural population of green anole lizards. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Wade J. Behavioural display systems across nine Anolis lizard species: sexual dimorphisms in structure and function. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:1711–1719. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger TJ, Revell LJ, Gibson-Brown JJ, Losos JB. Repeated modification of early limb morphogenesis programmes underlies the convergence of relative limb length in Anolis lizards. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2012;279:739–748. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe JJ, Revell LJ, Szekely B, Brodie ED, Losos JB. Convergent evolution of phenotypic integration and its alignment with morphological diversification in Caribbean Anolis ecomorphs. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution. 2011;65:3608–3624. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba-Takeuchi K, Mori AD, Kaynak BL, Cebra-Thomas J, Sukonnik T, Georges RO, Latham S, Beck L, Henkelman RM, Black BL, Olson EN, Wade J, Takeuchi JK, Nemer M, Gilbert SF, Bruneau BG. Reptilian heart development and the molecular basis of cardiac chamber evolution. Nature. 2009;461:95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature08324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckalbar WL, Lasku E, Infante CR, Elsey RM, Markov GJ, Allen AN, Corneveaux JJ, Losos JB, DeNardo DF, Huentelman MJ, Wilson-Rawls J, Rawls A, Kusumi K. Somitogenesis in the anole lizard and alligator reveals evolutionary convergence and divergence in the amniote segmentation clock. Dev Biol. 2012;363:308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke JC. Compilation of mRNA Polyadenylation Signals in Arabidopsis Revealed a New Signal Element and Potential Secondary Structures. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1457–1468. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Ji G, Haas BJ, Wu X, Zheng J, Reese GJ, Li QQ. Genome level analysis of rice mRNA 3'-end processing signals and alternative polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3150–3161. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SMC, Parra G, Ross E, Moore B, Holt C, Alvarado AS, Yandell M. MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2007;18:188–196. doi: 10.1101/gr.6743907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:ii215–ii225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Schöffmann O, Morgenstern B, Waack S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzman TB, Stroik LK, Julik E, Hutchins ED, Lasku E, Denardo DF, Wilson-Rawls J, Rawls JA, Kusumi K, Fisher RE. The Gross Anatomy of the Original and Regenerated Tail in the Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) Anat Rec. 2012;295:1596–1608. doi: 10.1002/ar.22524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, Birol I. ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.089532.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birol I, Jackman SD, Nielsen CB, Qian JQ, Varhol R, Stazyk G, Morin RD, Zhao Y, Hirst M, Schein JE, Horsman DE, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Marra MA, Jones SJM. De novo transcriptome assembly with ABySS. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2872–2877. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Schein J, Chiu R, Corbett R, Field M, Jackman SD, Mungall K, Lee S, Okada HM, Qian JQ, Griffith M, Raymond A, Thiessen N, Cezard T, Butterfield YS, Newsome R, Chan SK, She R, Varhol R, Kamoh B, Prabhu A-L, Tam A, Zhao Y, Moore RA, Hirst M, Marra MA, Jones SJM, Hoodless PA, Birol I. De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:909–912. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi K, Kulathinal RJ, Abzhanov A, Boissinot S, Crawford NG, Faircloth BC, Glenn TC, Janes DE, Losos JB, Menke DB, Poe S, Sanger TJ, Schneider CJ, Stapley J, Wade J, Wilson-Rawls J. Developing a community-based genetic nomenclature for anole lizards. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:554. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A, Götz S. Blast2GO: A Comprehensive Suite for Functional Analysis in Plant Genomics. International journal of plant genomics. 2008;2008:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, Robles M, Talon M, Dopazo J, Conesa A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Niu B, Gao Y, Fu L, Li W. CD-HIT Suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:680–682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater GSC, Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2325–2329. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Madan A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999;9:868–877. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT–-The BLAST-Like Alignment Tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Description of adult and embryonic tissues used for RNA-Seq.

Table S2. Orthology assignment of ASU_Acar genes.

Table S3. Orthology assignment of unmatched ASU_Acar annotated genes by Blast2GO.

Table S4. Orthology assignment of unmapped transcripts by Blast2GO.

Figure S1. Blast2GO matches for transcripts poorly aligning to the Anocar2.0 genome assembly. The species with the highest Blast2GO matches are shown.