Abstract

Background

Identifying risk factors for breast cancer specific to women in their forties could inform screening decisions.

Purpose

To determine what factors increase risk for breast cancer in women age 40–49 years and the magnitudes of risk for each factor.

Data Sources

MEDLINE (January 1996 to November 2011), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (fourth Quarter 2011), Scopus, and reference lists for published studies; and data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC).

Study Selection

English-language studies and systematic reviews of risk factors for breast cancer in women age 40–49 years. Additional inclusion criteria were applied for each risk factor.

Data Extraction

Data on participants, study design, analysis, follow-up, and outcomes were abstracted. Study quality was rated using established criteria and only studies rated good or fair were included. Results were summarized using meta-analysis when sufficient studies were available, or from the best evidence based on study quality, size, and applicability when meta-analysis was not possible. BCSC data were analyzed with proportional hazards models using partly conditional Cox regression. Reference groups for comparisons were set at U.S. population means.

Data Synthesis

65 studies provided data for estimates. Extremely dense breasts on mammography or first-degree relatives with breast cancer were associated with ≥2-fold increase in breast cancer. Prior breast biopsy, second degree relatives with breast cancer, or heterogeneously dense breasts were associated with 1.5–2.0 increased risk; current oral contraceptive use, nulliparity, and age ≥30 at first birth were associated with 1.0–1.5 increased risk.

Limitations

Studies varied by measures, reference groups, and adjustment for confounders; effects of multiple risk factors were not considered.

Conclusions

Extremely dense breasts and first degree relatives with breast cancer were each associated with ≥2-fold increased breast cancer risk in women age 40–49. Identification of these risk factors may be useful for personalized mammography screening.

Primary Funding Source

National Cancer Institute Activities to Promote Research Collaboration supplement (U01CA086076-10S1). Data collection was supported by the National Cancer Institute funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) cooperative agreement (U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, U01CA70040).

INTRODUCTION

Current practice guidelines regarding mammography screening differ in their recommendations for women in their forties (1–3). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends individualized, informed decision making about when to start mammography screening based on a woman’s values about benefits and harms (4). Risk based screening has been recommended for other health conditions in the U.S. and may provide a similar evidence based approach for breast cancer. Applying this approach to clinical practice has been problematic, however, because it is unclear how women and clinicians can effectively consider individualized risk factor information in their discussions of benefits and harms.

Microsimulation models of mammography screening developed as part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) indicated that women with approximately 2-fold increased risks for breast cancer who started biennial screening at age 40 had similar benefits (life-years gained) and harms (false positive results) as average risk women who started screening at age 50 (5). The risk threshold was higher when the CISNET models considered reduction in breast cancer deaths as a benefit (risk ratio [RR] 3.3), or annual rather than biennial screening (RR 4.3). These results suggested that identifying women with at least a 2-fold increased risk of breast cancer could be useful in determining whether to initiate mammography screening earlier than age 50.

A large research literature describes personal and clinical risk factors associated with breast cancer. However, studies generally included women of various ages, measured and reported risk factors in different ways, and provided wide ranges of risk estimates. Consequently, results of broad based epidemiologic studies may not be clinically applicable to the screening decisions of individual women and could be potentially misleading in some cases.

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to determine what factors increase risk for invasive breast cancer specifically for women age 40–49 years, and to estimate the magnitudes of risk for each factor compared to average risk women. It focuses on women who are eligible for screening mammography under current practice guidelines in the U.S., and considers average risk women to be those without the risk factor or who represent the mean or majority of women in the cohort, depending on the risk factor. This project was conducted in collaboration with development of the CISNET models of mammography screening based on increasing levels of risk, and builds on previous work (6, 7).

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

A standard protocol was developed and followed for this review. In conjunction with a research librarian, we used the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keyword nomenclature to search OVID MEDLINE (1996 to the second week of November 2011), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (4th Quarter 2011), and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4th Quarter 2011) for relevant English-language studies and systematic reviews. We also conducted secondary referencing by manually reviewing reference lists of papers and reviewing citations of key studies using Scopus. Searches included studies published during the past 16 years in order to provide data relevant to current cohorts of women considering mammography screening and to correspond to the timeframe of risk factor data collected by the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) also used in this study.

Study Selection

We developed inclusion and exclusion criteria for abstracts and articles based on the target population, included risk factors, and outcome measures. We included randomized controlled trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. After an initial review of abstracts, we retrieved full text articles and conducted a second review using additional inclusion criteria defined specifically for each risk factor, including eligibility of the data for statistical meta-analysis. When sufficient studies were not available to perform a meta-analysis, we used the best evidence based on study quality, size, and applicability determined by consensus among the investigators.

The target population consisted of women age 40–49 years who are eligible for screening mammography. Studies were excluded if they enrolled women who were not candidates for routine screening because they had previous breast or ovarian cancer; ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or other noninvasive breast cancer; current breast physical findings; presence of deleterious BRCA mutation in self or relatives; or prior chest radiation for conditions such as lymphoma. Included studies were conducted in countries with similar patient populations and health care services as the United States to assure applicability. Studies that reported outcomes in age groups that differed from the 40–49 year age category were included if the majority of subjects were 40–49, but none >55 years. When studies reported outcomes by menopausal status rather than age, we used results for premenopausal women as long as the group included a majority of women in their forties.

The main outcome measure was invasive breast cancer incidence at age 40–49 years, or invasive and noninvasive breast cancer as a combined outcome when this was the only measure reported in a study.

Risk factors included race/ethnicity, body mass index, physical activity, alcohol use, smoking, family history of breast cancer, breast density, prior breast procedures, and reproductive factors (age at menarche, parity, age at birth of the first child, breastfeeding, oral contraceptive use, menopausal age, status, and type, and menopausal hormone therapy). We defined explicit inclusion criteria separately for each risk factor as follows. Studies of risk factors for recent or current status reflected exposure within one year of breast cancer diagnosis. Studies of physical activity reported categories of exercise descriptively (inactive, some, regular) or quantified by metabolic equivalents (METs). Studies of alcohol use and smoking reported use status (current, former, never), recency, and amounts of use (e.g., drinks/wk or packs/day). Studies of oral contraceptive and menopausal hormone therapy use investigated any formulation (combination, progestin or estrogen only) and used various definitions of ever and never use. Studies of nonoral forms of contraception and those evaluating formulations not applicable to the target population were excluded (8).

We included studies that defined parity as the number of full term births, full term pregnancies, live births, or pregnancies continuing ≥6 months despite its outcome, consistent with standard medical definitions (9). Breastfeeding studies used a nonbreastfeeding group of parous women as the reference category, and determined breastfeeding activity (ever/never) and total duration.

Studies reporting menopausal status and history of hysterectomy or oophorectomy were included if they occurred prior to the diagnosis of breast cancer in women in their forties. We reviewed studies of mammographic breast density that categorized density using several methods, but reported results only from studies using the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) classification because of its clinical relevance to practice in the U.S. (1=almost entirely fat, 2=scattered fibroglandular densities, 3=heterogeneously dense, 4=extremely dense) (10).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

For the included studies, an investigator abstracted the following data: study design; setting; participant characteristics (including age, ethnicity, diagnosis); enrollment criteria; exposures (dose and duration); procedures for data collection; numbers enrolled and lost to follow-up; methods of exposure and outcome ascertainment; analytic methods including adjusting for confounders; and results for each outcome. A second investigator confirmed the accuracy of key data.

We used predefined criteria developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to assess the quality of studies (11). Two investigators independently rated the quality of each eligible study (good, fair, poor) and final ratings were determined by consensus among raters. We used only studies rated good or fair to determine risk estimates.

We assessed applicability of studies by following the population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, timing of outcomes measurement, and setting (PICOTS) format (12). In addition, applicability of case control studies was based on the control group population. For all studies, applicability was high if participants were recruited from predominantly community populations rather than clinical populations. For each risk factor, we also determined the consistency of results, that is, the degree of similarity in the effect sizes of the different studies. Studies were considered consistent if outcomes were generally in the same direction of effect and ranges of effect sizes were narrow. Applicability and consistency were determined by consensus of the investigators who reviewed the studies and conducted the meta-analyses.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

For eligible studies, we combined data in several meta-analyses to obtain more precise estimates of the relationship between risk factors and breast cancer. All included studies had cohort or case-control designs, and only studies reporting estimates that adjusted for at least one potential confounder in their analysis were included in the meta-analysis. To determine the appropriateness of meta-analysis, we considered clinical and methodological diversity and assessed statistical heterogeneity.

We abstracted or calculated estimates of risk ratios (odds ratio, rate ratio, or hazard ratio) and their standard errors from each study and used them as the effect measures. Since the incidence of breast cancer was very low, we considered the estimates of odds ratios to be equivalent to estimates of relative risks (rate ratio or hazard ratio). For most risk factors, studies reported risk ratios based on similar cut points across included studies and we used estimates based on the reported cut points. For BMI, the cut points were too disparate to be combined as reported in the published studies. Therefore, we combined BMI categories to correspond to the World Health Organization definitions of underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to <30 kg/m2), and obese (≥30 kg/m2) (13), combining underweight and normal weight categories because too few women were included in the underweight group. When studies categorized BMI using other cut points, we calculated risk ratios using assumptions that BMI is log-normally distributed and that there is a linear association between breast cancer risk and BMI on the logit scale. We estimated distribution parameters of BMI from published information from each study.

We assessed the presence of statistical heterogeneity among the studies using standard χ2 tests, and the magnitude of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (14). We used a random effects model to account for variation among studies. In general, when there is no variation among studies, the random effects model yields the same results as a fixed effects model without a study effect (15). To explore heterogeneity, we used meta-regression to assess the impact of the degree of adjustment for confounders in the original studies. This was quantified by the total number of adjusted variables and the number of adjusted risk factors considered in the review, and other study level variables such as quality, study design, and breast cancer type. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of results that considered variation from different definitions of risk factors and reference groups, inclusion of noninvasive breast cancer as an outcome, and outlying studies. The results of sensitivity analyses indicated no major differences from the main analysis.

For specific risk factors (BMI, age at menarche, age at birth of first child), we recalculated risk ratios from the meta-analysis using reference groups that differed from the original studies to approximate average risk in the population. The new reference groups were chosen to align with the distribution or mean of risk factors in the target population in order to provide more clinically relevant risk estimates. Data describing distributions or means in the target population were obtained from various sources representing U.S. national samples (16–22) (Appendix Table 1).

Comparison with Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Data

We included data from the BCSC to supplement the systematic review because some risk factors were not reported in published studies. The BCSC is a national collaboration of five mammography registries and two affiliate sites in the U.S. that prospectively collected data on breast imaging, risk factors, and breast cancer outcomes (23). We analyzed BCSC data collected from 1994 to 2010 for women age 40–49 at the time of their screening mammography examinations. Risk factor data were obtained at the time of each screening mammogram and reported in similar categories as those defined by the systematic review. Results for 380,585 women age 40–49 were provided in proportional hazards models adjusted for age, race, family history of breast cancer, and BMI and stratified by site. We used partly conditional Cox regression (24) to incorporate multiple observations per woman allowing her to enter the analysis at each eligible screening mammogram, and accounted for multiple observations per woman by using a robust sandwich estimator of the standard error (25). Women were followed until a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer or censoring at the first occurrence of DCIS, death, end of complete cancer follow-up for her site, age 50 years, disenrollment from Group Health for women at that site, or 5 years after the exam date. Mean length of follow-up was 3.3 years.

All analyses for the meta-analysis and BCSC data were performed using STATA/IC11.0 (26) and were reported as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Role of the Funding Source

The National Cancer Institute funded this work, but had no additional role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the review and analysis.

RESULTS

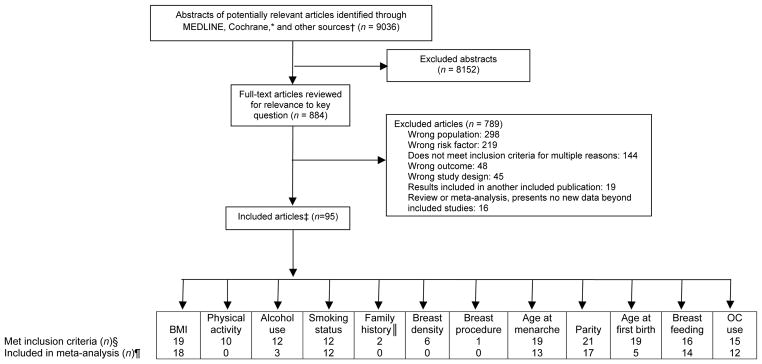

A total of 9036 abstracts were identified by search criteria; of these, 884 full-text articles were reviewed, and 95 met inclusion criteria as well as quality criteria for good or fair quality (Figure 1). Sixty one studies of 8 risk factors provided data for meta-analysis including BMI, alcohol use, smoking, age at menarche, parity, age at first birth, breastfeeding, and oral contraceptive use. Two published meta-analyses of family history of breast cancer reported results specifically for women in their forties (27, 28). Single studies provided estimates for 3 risk factors because either they were the only studies that met inclusion and quality criteria for the risk factor (prior breast procedure), or studies did not provide data that could be used in a meta-analysis (breast density, physical activity). Individual studies providing data for risk estimates are described in Appendix Table 2. BCSC data provided the only estimates for 3 risk factors that had no published studies meeting inclusion criteria (race/ethnicity, menopausal status and type, and menopausal hormone therapy). No data were available to evaluate age at menopause.

Figure 1. Literature search and selection.

BMI = body mass index; OC = oral contraceptive.

*Cochrane databases include the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

†Other sources include reference lists, Scopus, and studies suggested by experts.

‡Some articles are included for more than 1 risk factor.

§No articles met inclusion criteria for race/ethnicity, menopausal stage and type (surgical/nonsurgical), age at menopause, and menopausal hormone use.

||Published meta-analyses.

¶ Although some studies met inclusion criteria for the systematic review, they did provide data for the meta-analysis because they used dissimilar categories or different measures than the other included studies.

Personal Risk Factors

Personal risk factors included race/ethnicity, BMI, physical activity, alcohol use, and smoking (Table 1). BCSC data indicated no statistically significant increased risks for breast cancer by race/ethnicity using white race as the reference group.

Table 1.

Breast Cancer Risk Associated with Personal Factors for Women Age 40–49 Years

| Risk Factor | Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

|

BCSC Data*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n (Ref.) | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Test of Heterogeneity I2 (%); P value | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 0 | NA | Reference | |

| Black | 0 | NA | 1.04 (0.78–1.39) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | NA | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) | |

| Hispanic | 0 | NA | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | |

| Other/mixed | 0 | NA | 0.95 (0.77–1.17) | |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | ||||

| <18.5 | Reference | Reference† | 1.28 (0.98–1.66) | |

| 18.5–24 | Reference | |||

| 25–29 | 18 (17,29–45) | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | 0.0; 0.725 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) |

| ≥30 | 18 (17,29–45) | 0.74 (0.68–0.81) | 1.3; 0.439 | 0.74 (0.66–0.82) |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Inactive | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| Some | 1 (47) | 1.09 (0.88–1.34) | NA | |

| Regular | 1 (47) | 1.15 (0.93–1.43) | NA | |

| Alcohol use‡, drinks/wk | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| <7 | 3 (56,62,65) | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.0; 0.737 | NA |

| 7–13 | 3 (56,62,65) | 1.14 (0.94–1.38) | 0.0; 0.747 | NA |

| ≥14 | 3 (56,62,65) | 1.24 (0.87–1.78) | 38.5; 0.197 | NA |

| Smoking use | ||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| Ever | 12 (32,63,66–75) | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 31.0; 0.144 | NA |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| Current | 7 (32,63,68,71–74) | 0.92 (0.84–1.02) | 0.0; 0.842 | NA |

| Former | 7 (32,63,68,71–74) | 1.11 (0.97–1.28) | 47.8; 0.074 | NA |

BCSC = Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; CI = confidence interval; I2 = percentage of the variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity; NA = data not available.

Model included age, race, body mass index, family history of breast cancer, and site. Numbers of women included in estimates varied by risk factor because of missing data.

Included body mass index <25 kg/m2.

Among women using alcohol within 5 years.

For BMI, a meta-analysis of 18 studies (17, 29–45) indicated reduced risks for women in the overweight (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82–0.90) and obese (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.68–0.81) BMI categories compared to women in the normal/underweight category. Results were similar for overweight and obese categories in the BCSC, although the confidence interval included 1.00 for overweight. Data specifically for underweight women were not provided by the published studies, although the BCSC data indicated that risk for underweight women was not significantly different from normal weight.

Ten studies of physical activity met inclusion criteria (46–55), but could not be combined in the meta-analysis because they used different measures of activity and reported results in dissimilar categories. All studies reported no statistically significant differences in breast cancer risk based on physical activity. Results from a large, good-quality study designed to specifically assess the relationship between physical activity and premenopausal breast cancer provided estimates in Table 1 (47). Physical activity data were not available from the BCSC.

Although 12 studies reporting various measures of alcohol use met inclusion criteria (32, 37, 56–65), results from only 3 studies could be combined in the meta-analysis (56, 62, 65). Using no alcohol use as the reference group, results indicated higher risk estimates with increasing amounts of alcohol; however, all confidence intervals included 1.00. Smoking use and status (never/ever and never/current/former) had no significant associations with breast cancer based on meta-analyses of 12 studies of never versus ever use (32, 63, 66–75), and 7 studies of never versus current or former use (32, 63, 68, 71–74). No BCSC data on alcohol use or smoking were available.

Family History, Breast Density, Breast Procedures

In an analysis of data from 52 epidemiologic studies (27), breast cancer risk was significantly increased for women with first degree relatives with breast cancer (one relative RR 2.14; 95% CI 1.92–2.38; 2 relatives RR 3.84; 95% CI 2.37–6.22; ≥3 relatives RR 12.05; 95% CI 1.70–85.16) (Table 2). BCSC data also demonstrated higher risk for women with a first degree relative with breast cancer (RR 1.86; 95% CI 1.69–2.06). Risk was highest among women with first degree relatives who were diagnosed at younger compared to older ages for both the meta-analysis and BCSC results. Estimates for women with relatives <40 years old compared to women with no first-degree relatives were 3.0 (95% CI 1.8–4.9) in the meta-analysis (27), and 2.17 (95% CI 1.86–2.53) for women with relatives <50 in the BCSC. Risk was less for women with relatives ≥60 (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.3–2.1) (27). Risks were also significantly increased for women with ≥one second degree relatives compared to none in a meta-analysis of 2 studies (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4–2.0) (28).

Table 2.

Breast Cancer Risk Associated with Family History, Breast Density, and Breast Procedures for Women Age 40–49 Years

| Risk Factor | Systematic Review

|

BCSC Data*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n (Ref.) | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

| First-degree relatives with breast cancer, n | |||

| 0 | M (27) | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | M (27) | 2.14 (1.92–2.38) | None vs. any |

| 2 | M (27) | 3.84 (2.37–6.22) | 1.86 (1.69–2.06) |

| ≥3 | M (27) | 12.05 (1.70–85.16) | |

| Age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, y | |||

| None | M (27) | Reference | Reference |

| <40 | M (27) | 3.0 (1.8–4.9) | None vs. <50 |

| 40–49 | M (27) | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) | 2.17 (1.86–2.53) |

| 50–59 | M (27) | 2.3 (1.7–3.2) | None vs. ≥50 |

| ≥60 | M (27) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | 1.68 (1.44–1.96) |

| Second-degree relatives with breast cancer, n | |||

| 0 | M (28) | Reference | NA |

| ≥1 | M (28) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | NA |

| Breast density (BI-RADS category)† | |||

| 1 | 1 (76) | 0.46 (0.37–0.58) | 0.41 (0.31–0.55) |

| 2 | 1 (76) | Reference | Reference |

| 3 | 1 (76) | 1.62 (1.51–1.75) | 1.75 (1.59–1.93) |

| 4 | 1 (76) | 2.04 (1.84–2.26) | 2.33 (2.04–2.66) |

| Prior breast procedure‡ | |||

| None | 1 (77) | Reference | Reference |

| Any | 1 (77) | 1.87 (1.64–2.13) | 1.51 (1.36–1.67) |

BCSC = Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; BI-RADS = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; M = published meta-analysis; NA = data not available.

Model included age, race, body mass index, family history of breast cancer, and site. Numbers of women included in estimates varied by risk factor because of missing data.

1 = almost entirely fat; 2 = fibroglandular densities; 3 = heterogeneously dense; 4 = extremely dense.

Surgical and needle biopsies.

A published study of BCSC data reported breast density using BI-RADS categories and defined BI-RADS category 2 as the reference group (scattered fibroglandular densities) (76). Results indicated increased risk for categories 3 (RR 1.62; 95% CI 1.51–1.75) and 4 (RR 2.04; 95% CI 1.84–2.26) and reduced risk for category 1 (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.37–0.58).

A published study of BCSC data reported increased breast cancer risk for women who had prior benign breast biopsies (RR 1.87; 95% CI 1.64–2.13) (77). Additional BCSC data that included previous biopsy or fine needle aspiration also indicated increased risk (RR 1.51; 95% CI 1.36–1.67).

Reproductive Factors

Reproductive factors included age at menarche, parity, age at first birth, breastfeeding, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status, and menopausal hormone therapy (Table 3). In our meta-analysis of 13 studies (32, 35, 46, 78–87), menarche at age ≥15 years was associated with reduced risk for breast cancer compared to the reference age of 13 (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.78–0.97). BCSC results were similar.

Table 3.

Breast Cancer Risk Associated with Reproductive Factors for Women Age 40–49 Years

| Risk Factor | Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

|

BCSC Data*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n (Ref.) | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Test of Heterogeneity, I2 (%); P value | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Age at menarche, y | ||||

| ≤12 | 10 (32,35,46,78,80,81,83–86) | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 45.1; 0.059 | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) |

| 13 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| 14 | 6 (32,35,46,80,85,86) | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 3.8; 0.393 | 1.00 (0.85–1.17) |

| ≥15 | 9 (32,35,46,79,80,82,85–87) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 0; 0.584 | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) |

| Parity | ||||

| Ever | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| None | 17 (32,35,46,75,78–81,83–91) | 1.16 (1.04–1.26) | 80.3; <0.001 | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) |

| Births, n | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| 1 | 13 (32,35,75,78–81,83,85–88,91) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 48.3; 0.026 | NA |

| 2 | 13 (32,35,75,78–81,83,85–88,91) | 0.93 (0.77–1.12) | 73.2; <0.001 | NA |

| ≥3 | 13 (32,35,75,78–81,83,85–88,91) | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | 82.4; <0.001 | NA |

| Age at first birth, y | ||||

| <20 | 4 (35,46,78,84) | 0.96 (0.82–1.11) | 0; 0.811 | 0.78 (0.65–0.93) |

| 20–24 | 4 (35,46,78,84) | 0.96 (0.82–1.11) | 0; 0.622 | 0.87 (0.75–1.00) |

| 25–29 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| ≥30 | 5 (35,46,78,84,89) | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | 17.9; 0.300 | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) |

| None | 5 (35,46,78,84,89) | 1.25 (1.08–1.46) | 0; 0.548 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Breastfeeding† | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| Ever | 14 (35,75,79,81,83,84,87,91–97) | 0.87 (0.77–0.98) | 68.5; <0.001 | NA |

| Breastfeeding duration†, mo | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| <12 | 11 (35,79,81,83,84,92–97) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 42.2; 0.068 | NA |

| ≥12 | 11 (35,79,81,83,84,92–97) | 0.85 (0.73–0.99) | 55.0; 0.014 | NA |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| Ever | 12 (32,75,78,79,98–105) | 1.08 (0.96–1.23) | 71.5; 0.001 | NA |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||

| Former or none | 0 | NA | Reference | |

| Current | 0 | NA | 1.30 (1.13–1.49) | |

| Recency of oral contraceptive use, y | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | NA | |

| <5 | 8 (78,79,100–105) | 1.10 (0.93–1.29) | 40.7; 0.096 | NA |

| 5–9 | 8 (78,79,100–105) | 1.15 (0.94–1.40) | 51.8; 0.035 | NA |

| ≥10 | 8 (78,79,100–105) | 1.07 (0.95–1.19) | 40.1; 0.100 | NA |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Pre | 0 | NA | Reference | |

| Peri | 0 | NA | 0.70 (0.58–0.86) | |

| Post, nonsurgical | 0 | NA | 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | |

| Post, surgical‡ | 0 | NA | 0.58 (0.44–0.77) | |

| Unknown, surgery§ | 0 | NA | 0.67 (0.56–0.80) | |

| Menopausal hormone therapy|| | ||||

| Former or none | 0 | NA | Reference | |

| Current (no uterus) | 0 | NA | 0.70 (0.52–0.94) | |

| Current (uterus present) | 0 | NA | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | |

BCSC = Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; CI = confidence interval; I = percentage of the variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity; NA = data not available.

Model included age, race, body mass index, family history of breast cancer, and site. Numbers of women included in estimates varied by risk factor because of missing data.

Among women who gave birth.

Bilateral oophorectomy.

Usually hysterectomy without bilateral oophorectomy.

Assumed women without a uterus were using estrogen only and women with a uterus estrogen combined with progestin.

A meta-analysis of 17 studies of parity (32, 35, 46, 75, 78–81, 83–91) indicated that nulliparous women had a significantly increased risk for breast cancer compared to parous women (RR 1.16; 95% CI 1.04–1.26) similar to BCSC estimates (Table 3). Risk was significantly reduced for women with ≥3 births compared to none in a meta-analysis of 13 studies (32, 35, 75, 78–81, 83, 85–88, 91) (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.61–0.87). In a meta-analysis of 5 studies of age at first birth (35, 46, 78, 84, 89), women having their first child at age ≥30 had a higher risk for breast cancer compared to a reference group of women age 25–29 (RR 1.20; 95% CI 1.02–1.42), but slightly less than nulliparous women (RR 1.25; 95% CI 1.08–1.46). BCSC results indicated no significantly increased risks for these groups, but a decreased risk for women who were ≤20 at the time of the first birth.

Breastfeeding was associated with reduced risk for breast cancer among parous women in a meta-analysis of 14 studies (35, 75, 79, 81, 83, 84, 87, 91–97) (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77–0.98), particularly when breastfeeding continued for ≥12 months (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.73–0.99) (35, 79, 81, 83, 84, 92–97). Breastfeeding data were not available from the BCSC.

Twelve studies of oral contraceptive use provided estimates for the meta-analysis of ever use compared to none (32, 75, 78, 79, 98–105), and 8 studies provided estimates for recency of use with the most recent category defined as within 5 years (78, 79, 100–105). None of these associations were statistically significant, although all point estimates were increased (Table 3). BCSC data indicated significantly increased risk for breast cancer for current oral contraceptive use compared to former or non use (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.13–1.49).

BCSC data demonstrated reduced breast cancer risk for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (either surgical or nonsurgical menopause) compared to premenopausal women. BCSC women with no uterus currently using menopausal hormone therapy had a reduced risk for breast cancer compared to nonusers (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.52–0.95), while those with a uterus had no significant association. Presumably, women without a uterus were using estrogen alone while those with a uterus were using estrogen combined with progestin.

DISCUSSION

Ninety five studies identified in the systematic review contributed data for breast cancer risk estimates for 13 unique risk factors, while data from the BCSC provided estimates for 11, including 3 not included in published studies. Both sources provided estimates for some risk factors that were expressed in alternate ways, such as in dichotomous as well as ordinal categories. A summary of evidence for the systematic review describes for each risk factor, the number and design of included studies, cumulative samples sizes, breast cancer outcomes, and ratings for quality, consistency, and applicability (Table 4). Overall, studies were consistent and applicability was high, largely because conditions of the study population were incorporated into inclusion criteria.

Table 4.

Summary of Evidence for Studies Providing Data for Risk Estimates

| Number of Studies by Design, n

|

Cumulative Sample Sizes, n | Number of Studies by Breast Cancer Outcome, n

|

Number of Studies by Quality, n

|

Consistency* | Applicability† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Case-control | Published meta-analysis | Invasive only | Invasive and non-invasive | Not specified | Good | Fair | |||

| Body mass index | ||||||||||

| 9 | 9 | 0 | Cases: 7906 Controls: 11,092 Cohort: 316,518‡; 5562 events |

7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 13 | Consistent | High |

| Physical activity | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 116,671; 849 events | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Single study | High |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||||

| 0 | 3 | 0 | Cases: 5851 Controls: 4515 |

2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Consistent | High |

| Smoking use | ||||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 0 | Cases: 9560 Controls: 10,292 Cohort: 112,844; 1009 events |

5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 8 | Consistent | High |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| 0 | 7 | 0 | Cases: 7861 Controls: 8619 |

4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | Consistent | High |

| First degree relatives with breast cancer | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | Cases: 15,893 Controls: 24,517§ |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Single study | High |

| Age at diagnosis of first-degree relatives with breast cancer | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | Cases: 1158 Controls: 849 |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Single study | High |

| Second-degree relatives with breast cancer | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | Not provided | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Single study | High |

| Breast density | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 205,348; 3538 events | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Single study | High |

| Prior breast procedure | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 83,923|| | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Single study | High |

| Age at menarche | ||||||||||

| 1 | 12 | 0 | Cases: 10,797 Controls: 12,985¶ Cohort: 39,148; 478 events |

4 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 9 | Consistent | High |

| Parity | ||||||||||

| 3 | 14 | 0 | Cases: 11,253 Controls:17,386¶ Cohort: 63,118**; 837 events |

6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 13 | Consistent | High |

| Number of births | ||||||||||

| 2 | 11 | 0 | Cases: 9173 Controls:11,309¶ Cohort: 39,148**; 606 events |

3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 10 | Consistent | High |

| Age at first birth | ||||||||||

| 1 | 4 | 0 | Cases: 3992 Controls: 4923 Cohort: 23,970; 231 events |

2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Consistent | High |

| Breastfeeding | ||||||||||

| 1 | 13 | 0 | Cases: 6663 Controls: 8251¶ Cohort: 89,887; 256 events |

3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 13 | Consistent | High |

| Breastfeeding duration | ||||||||||

| 1 | 10 | 0 | Cases: 4765 Controls: 5992¶ Cohort: 89,887; 256 events |

2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 10 | Consistent | High |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||||||||

| 2 | 10 | 0 | Cases: 9016 Controls: 13,777 Cohort**; 1018 events |

7 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | Consistent | High |

| Recency of oral contraceptive use | ||||||||||

| 0 | 8 | 0 | Cases: 8484 Controls: 11,885 |

4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | Consistent | High |

Consistency refers to the degree of similarity in the effect sizes of different studies within an evidence base. Studies were consistent if outcomes were generally in the same direction of effect and ranges of effect sizes were narrow.

Applicability of case control studies was based on the control group population. For all studies, applicability was high if participants were recruited from predominantly community populations rather than clinical populations.

Two studies reported sample sizes for groups that could not be combined.

Sample size for one relative with breast cancer; numbers for more than one relative were not provided.

Number of events was not provided.

One study did not provide risk factor specific sample sizes and the total study sample size was used instead.

One study reported sample sizes for groups that could not be combined.

Results indicated that women in their forties with extremely dense breasts on mammography examination or at least one first degree relative with breast cancer had 2-fold or more increased risks for breast cancer (Table 5). This level of risk corresponds to the risk threshold of the CISNET models that demonstrated comparable benefits and harms for increased risk women starting biennial screening at age 40 as average risk women starting at age 50 (5). Women with two or more first degree relatives with breast cancer or first degree relatives diagnosed at <50 years had even higher risks.

Table 5.

Factors Significantly Associated with Increased Breast Cancer Risk for Women Age 40–49

| Risk Factor | Breast Cancer Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Source (Ref.) |

|---|---|---|

| Increase risk ≥2.0 | ||

| First-degree relatives with breast cancer, n | ||

| 1 | 2.14 (1.92–2.38) | (27) |

| 2 | 3.84 (2.37–6.22) | (27) |

| Any | 1.86 (1.44–1.96) | BCSC |

| Age of first-degree relative with breast cancer | ||

| <40 y | 3.0 (1.8–4.9) | (27) |

| <50 y | 2.17 (1.86–2.53) | BCSC |

| Breast density BI-RADS Category 4 | 2.04 (1.84–2.26) | (76)* |

| Increase risk 1.5–2.0 | ||

| Prior benign breast biopsy | 1.87 (1.64–2.13) | (77)* |

| Second-degree relative with breast cancer | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | (28) |

| Breast density BI-RADS Category 3 | 1.62 (1.51–1.75) | (76)* |

| Increase risk 1.0–1.5 | ||

| Current oral contraceptive use | 1.30 (1.13–1.49) | BCSC |

| Nulliparity† | 1.25 (1.08–1.46) | (35,46,78,84,89) |

| Age at first birth ≥30 y‡ | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | (35,46,78,84,89) |

BCSC = Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; BI-RADS = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; CI = confidence interval.

BCSC estimates from published analyses; similar BCSC estimates calculated from primary data are provided in Table 2.

Nulliparity was calculated in 2 ways (Table 3). Estimates indicating significantly increased risk for nonparous compared to parous women were similar for the meta-analysis and the BCSC data. Estimates comparing ages at first birth that included nonparous women provided significant results for the meta-analysis only.

Results were not statistically significant for the BCSC data.

Three factors were associated with increased risk between 1.5–2.0 including having had a prior benign breast biopsy, a second degree relative with breast cancer, and heterogeneously dense breast tissue. Current use of oral contraceptives, nulliparity, and first birth at age ≥30 were associated with increased risk between 1.0–1.5, although some results differed by data sources suggesting inconsistency. Several factors were associated with reduced risk from average including BMI ≥25 kg/m2, low breast density, age at menarche ≥15, birth of ≥3 children, breastfeeding among parous women, peri or postmenopausal status, and use of menopausal estrogen only hormone therapy.

While results of this review are consistent with previous research, our estimates of risk are unique and highly relevant to current clinical dilemmas about mammography screening for women in their forties. Although most women who develop breast cancer have no known risk factors, information about risk may be particularly useful when making decisions about screening. Importantly, several risk factors identified in single studies or in studies of women of various ages were not significant in our analysis. These findings may be useful to women, clinicians, and health systems considering risk based screening who find a long list of potential risk factors difficult to navigate. Focusing on high breast density and first degree family history of breast cancer may be a more clinically feasible approach to personalized screening.

Family history is an important and well established risk factor for breast cancer, and its importance in breast cancer screening and prevention extends beyond mammography. Current USPSTF recommendations for women with significant family histories include genetic counseling and mutation testing if appropriate (106), and consideration of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer (107).

Several studies have reported associations between mammographic breast density and breast cancer (108–112), but only one met inclusion criteria for this review because it reported results with BIRADs classifications that are used in U.S. clinical practice, and provided risk estimates specific to the target population (76). The use of breast density in screening and prevention is currently unclear, although research suggests it may serve an important role in estimating risk (112–115), and for determining ages to begin screening and appropriate screening intervals (116). Clinical trials of these strategies, however, have not yet been done and the use of breast density in current practice poses challenges, such as variability of reporting among radiologists (117).

Our risk estimates were derived from epidemiologic data and their application in predicting individual risk has not been evaluated. Our risk estimates may be particularly useful for developing more complex risk prediction models. Although several such models currently exist, such as the Gail model, they were not developed specifically for women in their forties, were not based on recent research, and have low discriminatory accuracy in predicting risk for individuals (118). Improving risk models and demonstrating their effectiveness in clinical applications are necessary future steps in this work.

Although our risk estimates may be useful in informing clinical practice, effective methods to modify risk factors to reduce breast cancer are largely untested. Our results indicated reduced breast cancer for women with BMIs in the overweight and obese categories. However, an inverse association has been demonstrated for postmenopausal women (119). Given the higher incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, an appropriate clinical recommendation would be to modify weight gain after menopause rather than at younger ages. Other risk factors, such as parity, may reflect underlying biologic effects that cannot be modified for disease prevention purposes, while breast density improved for high risk women using tamoxifen in clinical trials (120). How to apply this information to individual patients is currently unclear.

This evidence review and meta-analysis is limited in several ways. Studies reported different measures, dissimilar categories for exposures and outcomes, and reference groups that did not represent average risk in the target population. In addition, some women outside the targeted age group were included because studies provided data in categories that did not align with ours. Studies also varied in the degree of adjustment for confounders in the risk estimates. Publication bias and selective reporting are also potential limitations, but difficult to assess.

To address these issues, we developed inclusion criteria that considered the quality and applicability of studies consistently across risk factors; included only fair or good quality studies; selected best evidence estimates for risk factors that lacked estimates from a meta-analysis; and redefined reference groups to approximate the mean or distribution of the target population. In addition we analyzed primary BCSC data to supplement or support the meta-analysis results. To address concerns of heterogeneity, we performed several sensitivity analyses, including an analysis based on the degree of adjustment for confounders, and found no important differences in results.

Data in the meta-analysis and the BCSC were derived from observational studies that were subject to inherent potential biases, such as unmeasured and uncontrolled confounders. Our analysis was limited to the effects of individual risk factors and we did not assess the risk associated with multiple concurrent factors. Our inclusion criteria lead to the selection of studies enrolling a specifically defined population and results may not be applicable to different populations. Also, we focused on factors that increase risk for breast cancer in collaboration with the development of the CISNET models. Clinical application of our estimates of factors associated with reduced risk is limited because the CISNET models were not designed for comparable reduced risk scenarios.

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for breast cancer in 40–49 year old women, as well as primary analysis of the same risk factors using BCSC data, indicated that having either extremely dense breast tissue on mammography or first degree relatives with breast cancer are associated with 2-fold or more increased breast cancer risk. Identification of these risk factors may be useful for personalized mammography screening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The collection of Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) cancer data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the U.S. For a full description of these sources, please see: http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. We thank the participating women, mammography facilities, and radiologists for the data they have provided for this study. A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/.

Each cancer registry and the Statistical Coordinating Center (SCC) have received institutional review board approval for either active or passive consenting processes or a waiver of consent to enroll participants, link data, and perform analytic studies. All procedures are Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) compliant and all registries and the SCC have received a federal Certificate of Confidentiality and other protection for the identities of women, physicians, and facilities who are subjects of this research.

Rose Relevo, MLIS, MS and Robin Paynter, MA-LIS conducted literature searches, and Katie Reitel, BA provided assistance; all are affiliated with Oregon Health & Science University. Providence Health & Services provided additional support for Dr. Nelson, and Dr. Cantor was supported by the Veteran’s Affairs Women’s Health Fellowship.

References

- 1.Lee CH, Dershaw DD, Kopans D, Evans P, Monsees B, Monticciolo D, et al. Breast cancer screening with imaging: recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging and the ACR on the use of mammography, breast MRI, breast ultrasound, and other technologies for the detection of clinically occult breast cancer. J Am Coll of Radiol. 2010;7(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, Burke W, Costanza ME, Evans WP, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(3):141–69. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):372–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c98e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Ravesteyn N, Miglioretti D, Stout N, Lee S, Schechter C, Buist D, et al. What level of risk tips the balance of benefits and harms to favor screening mammography starting at age 40? Ann of Intern Med. 2011 doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00002. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–37. W237–42. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandelblatt JS, Cronin KA, Bailey S, Berry DA, de Koning HJ, Draisma G, et al. Effects of mammography screening under different screening schedules: model estimates of potential benefits and harms. Ann Int Med. 2009;151:738–747. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishell DR., Jr Oral contraception: past, present, and future perspectives. Int J Fertil. 1991;36 (Suppl 1):7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pernoll ML. Benson & Pernoll’s handbook of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 10. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Radiology: The American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) 4. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 Suppl):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkins D, Chang S, Gartlehner G, Buckley D, Whitlock E, Berliner E, et al. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jan, 2011. Assessing the Applicability of Studies When Comparing Medical Interventions. AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC019-EF. Available at http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Intitutes of Health. [accessed on September 2, 2011];Calculate Your Body Mass Index. Available at: http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A. Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):844–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Sun L, Guo H, Chiarelli A, Hislop G, et al. Body size, mammographic density, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2086–92. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: more women are having their first child later in life. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;(21):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;(29):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Report Card - United States. 2010 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard/reportcard2010.htm.

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2010: With Special Feature on Death and Dying. Hyattsville, MD: 2011. Overweight, obesity, and healthy weight among persons 20 years of age and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1960–1962 through 2005–2008. Table 71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343. Rockville, MD: 2008. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, Ernster VL, Rosenberg RD, Carney PA, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(4):1001–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng Y, Heagerty PJ. Partly conditional survival models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2005;61(2):379–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee E, Wei L, Amato D. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet. 2001:1389–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06524-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 1997;71(5):800–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970529)71:5<800::aid-ijc18>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franceschi S, Favero A, La Vecchia C, Baron AE, Negri E, Dal Maso L, et al. Body size indices and breast cancer risk before and after menopause. Int J Cancer. 1996:181–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960717)67:2<181::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Bryant HE. Case-control study of anthropometric measures and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2002:445–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Z, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, et al. Dual effects of weight and weight gain on breast cancer risk. JAMA. 1997:1407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson KC, Hu J, Mao Y Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group. Passive and active smoking and breast cancer risk in Canada, 1994–97. Cancer Causes Control. 2000:211–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008906105790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaaks R, Van Noord PA, Den Tonkelaar I, Peeters PH, Riboli E, Grobbee DE. Breast-cancer incidence in relation to height, weight and body-fat distribution in the Dutch “DOM” cohort. Int J Cancer. 1998:647–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980529)76:5<647::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahmann PH, Hoffmann K, Allen N, van Gils CH, Khaw K-T, Tehard B, et al. Body size and breast cancer risk: findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer And Nutrition (EPIC) Int J Cancer. 2004:762–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCredie M, Paul C, Skegg DC, Williams S. Reproductive factors and breast cancer in New Zealand. Int J Cancer. 1998:182–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980413)76:2<182::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michels KB, Terry KL, Willett WC. Longitudinal study on the role of body size in premenopausal breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2006:2395–402. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peacock SL, White E, Daling JR, Voigt LF, Malone KE. Relation between obesity and breast cancer in young women. Am J Epidemiol. 1999:339–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson CA, Coates RJ, Schoenberg JB, Malone KE, Gammon MD, Stanford JL, et al. Body size and breast cancer risk among women under age 45 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1996:698–706. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tehard B, Lahmann PH, Riboli E, Clavel-Chapelon F. Anthropometry, breast cancer and menopausal status: use of repeated measurements over 10 years of follow-up-results of the French E3N women’s cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2004:264–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Longnecker MP, Baron J, Greenberg ER, et al. Body size and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1997:1011–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vacek PM, Geller BM. A prospective study of breast cancer risk using routine mammographic breast density measurements. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(5):715–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verla-Tebit E, Chang-Claude J. Anthropometric factors and the risk of premenopausal breast cancer in Germany. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005:419–26. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiderpass E, Braaten T, Magnusson C, Kumle M, Vainio H, Lund E, et al. A prospective study of body size in different periods of life and risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004:1121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wenten M, Gilliland FD, Baumgartner K, Samet JM. Associations of weight, weight change, and body mass with breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Ann Epidemiol. 2002:435–4. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ziegler RG, Hoover RN, Nomura AM, West DW, Wu AH, Pike MC, et al. Relative weight, weight change, height, and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996:650–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.10.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen CL, White E, Malone KE, Daling JR. Leisure-time physical activity in relation to breast cancer among young women. Cancer Causes Control. 1997:77–84. doi: 10.1023/a:1018439306604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colditz GA, Feskanich D, Chen WY, Hunter DJ, Willett WC. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women. Br J Cancer. 2003:847–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Britton JA, Kelsey JL, Coates RJ, Brogan D, et al. Recreational physical activity and breast cancer risk among women under age 45 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1998:273–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilliland FD, Li YF, Baumgartner K, Crumley D, Samet JM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in hispanic and non-hispanic white women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001:442–50. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howard RA, Leitzmann MF, Linet MS, Freedman DM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk among pre- and postmenopausal women in the U.S. Radiologic Technologists cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2009:323–33. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lahmann PH, Friedenreich C, Schuit AJ, Salvini S, Allen NE, Key TJ, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007:36–42. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maruti SS, Willett WC, Feskanich D, Rosner B, Colditz GA. A prospective study of age-specific physical activity and premenopausal breast cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2008;100(10):728–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steindorf K, Schmidt M, Kropp S, Chang-Claude J. Case-control study of physical activity and breast cancer risk among premenopausal women in Germany. Am J Epidemiol. 2003:121–30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thune I, Brenn T, Lund E, Gaard M. Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997:1269–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verloop J, Rookus MA, van der Kooy K, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in women aged 20–54 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000:128–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berstad P, Ma H, Bernstein L, Ursin G. Alcohol intake and breast cancer risk among young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008:113–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowlin SJ, Leske MC, Varma A, Nasca P, Weinstein A, Caplan L. Breast cancer risk and alcohol consumption: results from a large case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 1997:915–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brinton LA, Gammon MD, Malone KE, Schoenberg JB, Daling JR, Coates RJ. Modification of oral contraceptive relationships on breast cancer risk by selected factors among younger women. Contraception. 1997:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferraroni M, Decarli A, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Alcohol consumption and risk of breast cancer: a multicentre Italian case-control study. Eur J Cancer. 1998:1403–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garland M, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Spiegelman DL, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Alcohol consumption in relation to breast cancer risk in a cohort of United States women 25–42 years of age. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999:1017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mannisto S, Virtanen M, Kataja V, Uusitupa M, Pietinen P. Lifetime alcohol consumption and breast cancer: a case-control study in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2000:11–8. doi: 10.1017/s1368980000000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McDonald JA, Mandel MG, Marchbanks PA, Folger SG, Daling JR, Ursin G, et al. Alcohol exposure and breast cancer: results of the women’s contraceptive and reproductive experiences study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2106–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morris Brown L, Gridley G, Wu AH, Falk RT, Hauptmann M, Kolonel LN, et al. Low level alcohol intake, cigarette smoking and risk of breast cancer in Asian-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010:203–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petri AL, Tjonneland A, Gamborg M, Johansen D, Hoidrup S, Sorensen TIA, et al. Alcohol intake, type of beverage, and risk of breast cancer in pre- and postmenopausal women. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 2004:1084–90. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130812.85638.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swanson CA, Coates RJ, Malone KE, Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Brogan DJ, et al. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk among women under age 45 years. Epidemiol. 1997:231–7. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al-Delaimy WK, Cho E, Chen WY, Colditz G, Willet WC. A prospective study of smoking and risk of breast cancer in young adult women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Band PR, Le ND, Fang R, Deschamps M. Carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting effects of cigarette smoke and risk of breast cancer. Lancet. 2002:1044–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baron JA, Newcomb PA, Longnecker MP, Mittendorf R, Storer BE, Clapp RW, et al. Cigarette smoking and breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996:399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Braga C, Negri E, La Vecchia C, Filiberti R, Franceschi S. Cigarette smoking and the risk of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1996:159–64. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gammon MD, Eng SM, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Kabat GC, Hatch M, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and breast cancer incidence. Environ Res. 2004:176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Teitelbaum SL, Brinton LA, Potischman N, Swanson CA, et al. Cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk among young women (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1998:583–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1008868922799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kropp S, Chang-Claude J. Active and passive smoking and risk of breast cancer by age 50 years among German women. Am J Epidemiol. 2002:616–26. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prescott J, Ma H, Bernstein L, Ursin G. Cigarette smoking is not associated with breast cancer risk in young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007:620–2. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roddam AW, Pirie K, Pike MC, Chilvers C, Crossley B, Hermon C, et al. Active and passive smoking and the risk of breast cancer in women aged 36–45 years: a population based case-control study in the UK. Br J Cancer. 2007:434–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wrensch M, Chew T, Farren G, Barlow J, Belli F, Clarke C, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer in a population with high incidence rates. Breast Cancer Res. 2003:R88–102. doi: 10.1186/bcr605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DSM, Cummings SR, Vachon C, Vacek P, et al. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(24):3830–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ashbeck EL, Rosenberg RD, Stauber PM, Key CR. Benign breast biopsy diagnosis and subsequent risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(3):467–72. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Althuis MD, Brogan DD, Coates RJ, Daling JR, Gammon MD, Malone KE, et al. Breast cancers among very young premenopausal women (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2003:151–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1023006000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang-Claude J, Eby N, Kiechle M, Bastert G, Becher H. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by age 50 among women in Germany. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11(8):687–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1008907901087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clavel-Chapelon F EN EPIC Group. Differential effects of reproductive factors on the risk of pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer. Results from a large cohort of French women. Br J Cancer. 2002:723–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gilliland FD, Hunt WC, Baumgartner KB, Crumley D, Nicholson CS, Fetherolf J, et al. Reproductive risk factors for breast cancer in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: the New Mexico Women’s Health Study. Am Journal Epidemiol. 1998:683–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/148.7.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR, Potter JD, Bernstein L, Marchbanks PA, et al. Timing of menarche and first full-term birth in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2008:230–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shantakumar S, Terry MB, Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Millikan RC, Moorman PG, et al. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007:365–74. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sweeney C, Baumgartner KB, Byers T, Giuliano AR, Herrick JS, Murtaugh MA, et al. Reproductive history in relation to breast cancer risk among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women. Cancer Causes Control. 2008:391–401. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9098-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Talamini R, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Borsa L, Montella M, et al. The role of reproductive and menstrual factors in cancer of the breast before and after menopause. Eur J Cancer. 1996:303–10. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00615-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Titus-Ernstoff L, Longnecker MP, Newcomb PA, Dain B, Greenberg ER, Mittendorf R, et al. Menstrual factors in relation to breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998:783–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu AH, Ziegler RG, Pike MC, Nomura AM, West DW, Kolonel LN, et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors and risk of breast cancer in Asian-Americans. Br J Cancer. 1996:680–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palmer JR, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. Dual effect of parity on breast cancer risk in African-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003:478–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reinier KS, Vacek PM, Geller BM. Risk factors for breast carcinoma in situ versus invasive breast cancer in a prospective study of pre- and post-menopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007:343–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tryggvadottir L, Tulinius H, Eyfjord JE, Sigurvinsson T. Breast cancer risk factors and age at diagnosis: an Icelandic cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2002:604–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ursin G, Bernstein L, Wang Y, Lord SJ, Deapen D, Liff JM, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of breast carcinoma in a study of white and African-American women. Cancer. 2004:353–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, Vena JE, Moysich KB, Muti P, Laughlin R, et al. Lactation history and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1997:932–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marcus PM, Baird DD, Millikan RC, Moorman PG, Qaqish B, Newman B. Adolescent reproductive events and subsequent breast cancer risk. Am J Public Health. 1999:1244–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Michels KB, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Manson JE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Prospective assessment of breastfeeding and breast cancer incidence among 89,887 women. Lancet. 1996:431–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Negri E, Braga C, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Talamini R, Franceschi S. Lactation and the risk of breast cancer in an Italian population. Int J Cancer. 1996:161–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960717)67:2<161::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stuver SO, Hsieh CC, Bertone E, Trichopoulos D. The association between lactation and breast cancer in an international case-control study: a re-analysis by menopausal status. Int J Cancer. 1997:166–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<166::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Troisi R, Weiss HA, Hoover RN, Potischman N, Swanson CA, Brogan DR, et al. Pregnancy characteristics and maternal risk of breast cancer. Epidemiol. 1998:641–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dumeaux V, Lund E, Hjartaker A. Use of oral contraceptives, alcohol, and risk for invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004:1302–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of oral contraceptive use and risk of breast cancer (Nurses’ Health Study, United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1997:65–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1018435205695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, Folger SG, Mandel MG, Daling JR, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002:2025–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moorman PG, Millikan RC, Newman B. Oral contraceptives and breast cancer among African-american women and white women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001:329–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Newcomb PA, Longnecker MP, Storer BE, Mittendorf R, Baron J, Clapp RW, et al. Recent oral contraceptive use and risk of breast cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1996:525–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00051885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Rao RS, Zauber AG, Strom BL, Warshauer ME, et al. Case-control study of oral contraceptive use and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1996:25–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosenberg L, Zhang Y, Coogan PF, Strom BL, Palmer JR. A case-control study of oral contraceptive use and incident breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2009:473–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Skegg DC, Paul C, Spears GF, Williams SM. Progestogen-only oral contraceptives and risk of breast cancer in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control. 1996:513–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00051883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.U S. Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(5):355–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-5-200509060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Chemoprevention of breast cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):56–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007:227–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I, McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006:1159–69. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thomas DB, Carter RA, Bush WH, Jr, Ray RM, Stanford JL, Lehman CD, et al. Risk of subsequent breast cancer in relation to characteristics of screening mammograms from women less than 50 years of age. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002:565–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ursin G, Ma H, Wu AH, Bernstein L, Salane M, Parisky YR, et al. Mammographic density and breast cancer in three ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003:332–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vachon CM, van Gils CH, Sellers TA, Ghosh K, Pruthi S, Brandt KR, et al. Mammographic density, breast cancer risk and risk prediction. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;9(6):217. doi: 10.1186/bcr1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, Vacek PM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Carney PA, et al. Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(17):1204–14. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, Graubard B, Schairer C, Byrne C, et al. Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(17):1215–26. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, Kerlikowske K. Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94(2):115–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-5152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schousboe J, Kerlikowske K, Loh A, Cummings S. Personalizing mammography by breast density and other risk factors for breast cancer: analysis of health benefits and cost-effectiveness. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):10–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nicholson BT, LoRusso AP, Smolkin M, Bovbjerg VE, Petroni GR, Harvey JA. Accuracy of assigned BI-RADS breast density category definitions. Acad Radiol. 2006:1143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nelson H, Fu R, Smith M, Griffin J, Nygren P, Humphrey L. Comparative Effectiveness Review (Prepared by the Oregon Health & Science University Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No 290–97–0018) Rockville, MD: Sep, 2009. Comparative Effectiveness of Medications to Reduce Risk for Primary Breast Cancer in Women. [Google Scholar]

- 119.van den Brandt PA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson L, Folsom AR, et al. Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000:514–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, Duffy SW, Cawthorn S, Howell A, et al. Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):744–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data