Abstract

BACKGROUND

Buprenorphine is increasingly being used in community-based treatment programs, but little is known about the optimal level of psychosocial counseling in these settings. The aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness of OP and IOP level counseling when provided as part of buprenorphine treatment for opioid-dependent African Americans.

METHODS

Participants were African American men and women starting buprenorphine treatment at one of two community-based clinics (N=300). Participants were randomly assigned to OP or IOP. Measures at baseline, 3- and 6-months included the primary outcome of DSM-IV opioid and cocaine dependence criteria, as well as additional outcomes of illicit opioid and cocaine use (urine test and self-report), criminal activity, retention in treatment, Quality of Life, Addiction Severity Index composite scores, and HIV risk behaviors.

RESULTS

Participants assigned to OP received, on average, 3.67 (SD=1.30) hours of counseling per active week in treatment. IOP participants received an average of 5.23 (SD=1.68) hours of counseling per active week (less than the anticipated 9 hours per week of counseling). Both groups showed substantial improvement over a 6-month period on nearly all measures considered. There were no significant differences between groups in meeting diagnostic criteria for opioid (p=.67) or cocaine dependence (p=.63). There were no significant between group differences on any of the other outcomes. A secondary analysis restricting the sample to participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for baseline cocaine dependence also revealed no significant between-group differences (all ps>.05).

CONCLUSIONS

Buprenorphine patients receiving OP and IOP levels of care both show short-term improvements.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, IOP, African Americans, CIDI-2, Quality of life

1. INTRODUCTION

Buprenorphine, an effective treatment for opioid dependence (Mattick et al., 2008), has been available in the U.S. for a decade. The regulatory structure surrounding buprenorphine in the U.S. allows the medication to be delivered in a wider range of clinical venues than methadone, which is available primarily through specialized, highly regulated Opioid Treatment Programs (Jaffe and O’Keeffe, 2003). Patients receiving buprenorphine can usually receive take-home medication on an accelerated schedule and fill prescriptions at a community pharmacy, depending on the clinical setting in which they are seen. Thus, patients and treatment providers are both afforded greater flexibility with buprenorphine than with methadone. However, diffusion of buprenorphine throughout the publically-supported treatment system has been slow (Ducharme et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2006; Knudsen et al., 2006). As a result, individuals who lacked health insurance and relied on publicly-funded treatment, a group consisting largely of low-income minorities, often have not had equal access to buprenorphine and limited research exists focusing on minority populations receiving buprenorphine treatment.

Maryland has included buprenorphine on its Medicaid formulary since 2003 and, beginning in 2006, Baltimore’s substance abuse authority offered grants or contracts to existing drug treatment providers who were willing to adopt buprenorphine. These initiatives led to increased access to buprenorphine treatment in the public treatment sector in Baltimore, where the heroin-dependent population is predominantly African American.

Intensive Outpatient vs. Standard Outpatient Treatment

The American Society of Addiction Medicine Patient Placement Criteria (ASAM PPC), classifies outpatient care into Level I (Standard Outpatient [OP], typically 2–8 hours of counseling per week) and Level II (Intensive OP [IOP], typically a minimum of 9 hours per week). Both IOP and OP treatments are in widespread use in the US (SAMHSA, 2007) and ASAM levels of care are often tied to different reimbursement schedules for payers. Yet, surprisingly, there is a relative lack of evidence from clinical trials on the comparative effectiveness of IOP vs. OP treatment. One randomized trial that compared IOP to OP treatment among 447 cocaine-dependent patients found no significant differences between treatments at 9-month follow-up on Addiction Severity Index (ASI) composite scores, or drug testing (Gottheil et al., 1998). A naturalistic longitudinal study comparing 6 IOPs and 10 OPs found no significant differences between the patients in terms of substance use, health, or social functioning at 6-month follow-up (McLellan et al., 1997).

Most outpatient programs in Baltimore that adopted buprenorphine did so within the existing framework of the ASAM PPC. The programs in the study were typically structured to provide IOP-level care in the early stages (5–7 weeks) of treatment, after which patients would switch to the less intensive OP level of care. Ultimately, the goal was to facilitate patients’ transition to ongoing buprenorphine treatment at a primary care provider. The system in Baltimore was structured to start individuals in IOP under the assumption that “more is better” early in treatment. However, empirical data on the relative effectiveness of OP compared to IOP levels of care in buprenorphine treatment was lacking.

The primary goal of the current study was to compare the relative effectiveness of IOP and OP levels of care among African Americans receiving buprenorphine. The study’s primary outcome measures were DSM-IV criteria for opioid and cocaine dependence. We hypothesized that, on an intent-to-treat basis, participants in OP would have superior outcomes to participants in IOP. This hypothesis was based on the expectation that the higher compliance burden of IOP would lead to premature discontinuation of treatment.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The study was designed as a parallel two-group randomized trial, in which newly admitted patients were randomly assigned to receive either OP or IOP levels of care in addition to buprenorphine. This intent-to-treat study examined OP and IOP as actually delivered by two publicly-funded outpatient treatment programs that had adopted buprenorphine.

2.2. Participants

Participants were African American adults newly-admitted to buprenorphine treatment at one of the participating treatment programs (N=300). Racial status was determined by the participant’s self-report. In order to be enrolled in the study, participants had to have been admitted to buprenorphine treatment at the program, received at least one buprenorphine dose, and received fewer than 8 hours of counseling prior to random assignment. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, an acute medical or psychiatric illness beyond the ability of the program physician to manage, or insufficient cognitive capacity to provide informed consent.

The study was approved by the Friends Research Institute’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Sheppard Pratt IRB (parent organization of one of the study sites) for the protection of human subjects. All participants provided informed consent. A Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for the study. Participant baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Total Sample (n=300) | OP (n=155) | IOP(n=145) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Gender, n(%) | 113 (37.67) | 62 (40.00) | 51 (35.17) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.09 (6.45) | 46.75 (6.10) | 45.38 (.56) |

| Married, n(%) | 31 (10.33) | 15 (9.68) | 16 (11.03) |

| Employed in past 30d, n(%) | 108 (36.00) | 55 (35.48) | 53 (36.55) |

| Years of Education, mean (SD) | 11.48 (1.61) | 11.56 (1.60) | 11.39 (.13) |

| Number of lifetime hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 2.99 (5.06) | 3.00 (4.48) | 2.98 (.47) |

| No previous opiate agonist treatment, n(%) | 92 (30.67) | 41 (26.45) | 51 (35.17) |

| Previous buprenorphine treatment only, n(%) | 87 (29.00) | 47 (30.32) | 40 (27.59) |

| Previous methadone treatment only, n(%) | 55 (18.33) | 30 (19.35) | 25 (17.24) |

| Previous buprenorphine and methadone treatment, n(%) | 66 (22.00) | 37 (23.87) | 29 (20.00) |

| Injection drug user, n(%) | 70 (23.33) | 41(26.45) | 29 (20.00) |

| Cocaine use in last 30d or cocaine+ urine, n(%) | 184 (61.33) | 87 (56.13) | 97 (66.90) |

2.3. Treatment Sites

This study was conducted in two formerly drug-free outpatient programs that had adopted buprenorphine and provided treatment free of charge to uninsured patients through publicly-funded treatment slots. These clinics also facilitated the enrollment of patients in the government health insurance plan (Medicaid). One site was a drug treatment program co-located within a large community health center, the other was a free-standing drug treatment program affiliated with (and located adjacent to) an outpatient community mental health clinic. Both clinics had been providing buprenorphine treatment since 2006, were located in impoverished urban communities, and served a predominantly African American population. Both sites were well-represented in the study, comprising 53% and 47% of the final participant sample.

2.4. Procedures

From March 2010 to March 2011 patients being admitted to buprenorphine treatment at each participating program were approached by a trained research assistant (RA) and screened for eligibility. After the participant provided informed consent and completed baseline assessment procedures, the RA opened a sealed, opaque envelope provided by the project manager to assign the participant to OP or IOP. Block randomization was used, such that for each block of four participants, two were assigned at random to each condition.

Dose induction in both Conditions typically started with buprenorphine/naloxone combination between 4 and 8 mg, and increased to an individually determined dose. Most patients achieved a maintenance dose between 8–24 mg daily.

Patients received supervised dose administration in the clinics during the early stages of treatment (typically for the first several weeks), and gradually switched to unsupervised buprenorphine/naloxone combination through prescriptions written by the clinic physician. Participants were permitted to remain on buprenorphine as long as clinically indicated and desired by the patient. After a period of stabilization (typically after 6 months), patients were to be linked to primary care physicians for continued buprenorphine treatment, at which time they could continue receiving counseling at the treatment program.

2.4.1. Treatment Conditions

At both sites, the key distinctions between IOP and OP were frequency and content of individual and group counseling sessions. The majority of counseling in both Conditions was delivered in group format.

Intensive Outpatient (IOP)

IOP was intended to provide at least 9 hours per week of counseling for a planned duration of approximately 45 days. Counseling was to be provided four days per week, for at least two hours per day, plus one weekly individual session. In practice, several group meetings per week were typically conducted by counseling staff. These groups usually had a topical focus such as substance abuse education, relapse prevention, medication education, HIV prevention, health promotion, and women’s support groups. Twelve-step meeting attendance was encouraged. Following IOP, patients typically continued in an OP level of care at the same program. Eventually (generally starting at around 6 months), patients were transferred to ongoing buprenorphine treatment delivered by a primary care physician.

Outpatient Counseling (OP)

Outpatient counseling was expected to entail a minimum of one group and one individual session per week, but could include up to 8 hours of counseling per week (typically delivered in group settings). Twelve-step meeting attendance was also encouraged and relapse prevention groups were offered weekly. Participants assigned to OP received the same counseling schedule as clinic patients who had transitioned to OP after an initial period in IOP. As in the IOP condition, patients were eventually transferred to ongoing buprenorphine treatment by a primary care physician.

2.5. Assessments

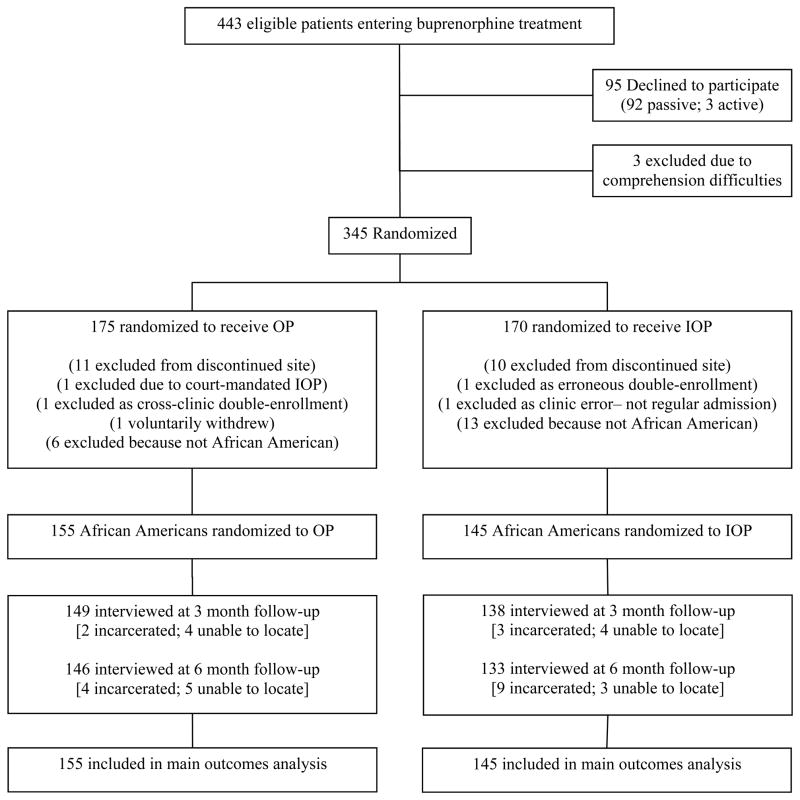

Participants were administered a battery of instruments (described below) at study entry and again at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Participants were paid $30 for completing the baseline interview and $40 for each follow-up interview. A trained RA conducted all interviews face-to-face. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of the interview and that their responses would not be shared with anyone outside of the study (including clinic staff). A urine sample was obtained at each interview. A high rate of follow-up was achieved (95.7% at 3 months; 93.0% at 6 months). A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram is shown in Figure 1 (Schulz et al, 2010).

Figure 1. Study flow.

- Passive declines included failure to keep enrollment appointments after expressing initial interest in the study.

- Active declines included direct verbal refusal to participate after discussing the study with research personnel.

- Comprehension Difficulties included severe cognitive impairment/inability to respond to basic questions.

- Randomization was conducted through a block random assignment procedure, such that in each block of 4 participants 2 were assigned to each condition. Participants and interviewers were blind to assignment during the baseline interview.

-

Follow-up rates:3 months: 95.7% (overall); 96.1% (OP condition); 95.2% (IOP condition).6 months: 93.0% (overall); 94.2% (OP condition); 91.7% (IOP condition).

2.6. Measures

Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-2)

Dependence criteria for opioids and cocaine were determined using items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-2; World Health Organization, 2004) corresponding to each of the symptoms outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4thedition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The CIDI-2 has been recommended as the instrument of choice for measuring dependence criteria by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (Forman et al., 2004).

Several careful modifications were made to ensure interpretable results and facilitate detection of short-term changes in dependence symptoms. At baseline, the dependence symptom questions were asked in the typical 12-month time frame used for DSM-IV diagnoses. However, since the follow-up period for the study was only six months, the time frame for the symptom questions was switched to the past 30 days at each follow-up. One additional modification was made to the opioid dependence criteria. Normally, the blanket qualifier “on agonist treatment” applies to anyone treated with agonist medications and precludes classification of remission of any kind (early/sustained; partial/full). However, we assessed dependence on opioids that were used non-medically, and instructed participants not to count symptoms related to buprenorphine taken as prescribed.

Urine Drug Testing

Urine samples were collected by research staff at each assessment and were tested by a certified laboratory by Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay for morphine (heroin metabolite) and benzoylecgonine (cocaine metabolite). Missing or non-sufficient urine samples were excluded.

Addiction Severity Index

The 5th edition of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was used to obtain self-reported days of heroin use, cocaine use, and criminal activity within the last 30 days. The medical, employment, alcohol, drug, legal, family/social, and psychiatric composite scores from the ASI (McLellan et al., 1992) were also examined. Various participant background characteristics (e.g., gender, injection drug use status, etc.) were also taken from the ASI.

WHOQOL-BREF

Participants’ quality of life was assessed using the WHOQOL-BREF, an abbreviated version of the widely used WHOQOL instrument (World Health Organization, 2004). The WHOQOL-BREF provides Quality of Life scores from 1–100 for four distinct domains: Physical, Psychological, Social, and Environmental. Each subscale was examined separately in the current study.

Risk Assessment Battery (RAB)

HIV risk behaviors were gauged at each interview time point using the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB), a structured interview that has been widely used in drug abuse studies (Metzger et al., 1993). The subscale scores for injection and sexual risk were used in the present study as indices of HIV risk behaviors.

Clinic Records

Clinic records at each site were used to obtain information on daily buprenorphine dosing, weekly counseling received (individual and group), and days in treatment. Treatment retention was operationally defined as being in buprenorphine treatment at the original program or another provider (because the clinics had the goal of eventually transferring patients to office-based buprenorphine). Participants who had successfully transitioned to physician-based buprenorphine treatment at 6 month follow-up were considered retained for 180 days.

The average weekly hours of counseling per active week in treatment was computed for each participant. This variable provides a metric of exposure to behavioral counseling services, adjusted for differing lengths of stay.

Supplemental Questionnaire

A supplemental study questionnaire was used to measure perceived patient burden and treatment satisfaction. The measure of patient burden, adapted from a similar measure used in medical studies (Bernhard et al., 2002), asked participants to rate on a simple visual scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 100 (“a lot”) the degree to which they were bothered by: (a) time and cost of travel to the clinic; (b) rules and regulations of the clinic; (c) having to attend individual counseling; (d) having to attend group counseling; (e) having to attend drug education; (f) having to take buprenorphine; and (g) their overall treatment experience. Perceptions of burden were assessed at the 3 month follow-up, both retrospectively for the first month of treatment, and during the most recent month (for participants still in treatment).

Patient satisfaction was assessed at each follow-up point with the question “How satisfied were/are you with the treatment you received at the program overall?” Response categories used a 5-point Likert-type scale (“very dissatisfied”, “somewhat dissatisfied”, “neither satisfied or dissatisfied”, “somewhat satisfied”, “very satisfied”).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Outcomes were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis, examining differential change over time between the two treatment conditions. A Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) framework was used to account for repeated measurement on participants, using logistic models for binary outcomes (urine test results, DSM-IV dependence criteria), overdispersion-corrected Poisson models for count outcomes (days of heroin use, cocaine use, days of criminal activity derived from the ASI), and Gaussian models for continuous outcomes (ASI composite scores, WHOQOL-BREF quality of life domain scores, RAB HIV risk behavior drug and sex risk scores). GEE models were specified with unstructured correlations for Time and robust standard errors, and examined outcomes as a function of Time, Condition, and their interaction (the treatment effect). Retention was examined in a survival analysis using proportional-hazards Cox regression. For all analyses, findings of the unadjusted models presented here were confirmed in conditional models that adjusted for gender, age, injection drug use, program site, and buprenorphine dose.

In addition to the analyses comparing OP vs. IOP conditions, a parallel analysis was conducted to examine the impact of counseling frequency as a continuous variable, irrespective of group assignment. These GEE models tested the interaction between assessment time point and average number of counseling hours per active treatment week, controlling for the constituent main effects of the interaction and the number of days retained in treatment.

Since we were also interested in learning what patient factors might influence treatment success, and IOP treatment could potentially confer therapeutic benefits not conferred by OP for those patients who also have non-opioid drug problems (which buprenorphine alone would not adequately address), we conducted a secondary analysis in which the sample was restricted to participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence at baseline. The analysis strategy mirrored that of the main analysis, except for the opioid and cocaine dependence outcomes which were analyzed separately for 3- and 6-month endpoints due to insufficient baseline variation for the GEE models.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of IOP and OP

Services Received

Participants in the OP condition received, on average, 3.67 (SD=1.30) hours of counseling per active week in treatment. In contrast, participants in IOP received an average of 5.23 (SD=1.68) hours of counseling per active week in treatment. Although the difference in total counseling exposure between the groups amounted to less than 2 hours per week, this difference was statistically significant (independent samples t-test=−9.04; p< .001). In both conditions, more services were received in the early weeks of treatment, with most service exposure driven by group-level counseling. Participants in OP and IOP, respectively, received an average of just .27 (SD=.19) and .31 (SD=.16) hours of individual-level counseling per active treatment week (independent samples t-test=−2.01; p< .05).

Burden

Participants reported low patient burden, with a mean rating of overall treatment burden of 22.8 (SD=28.4) on a scale of 1–100 for the first month of treatment. There were no significant differences in perceptions of burden between OP and IOP for the first month of treatment, either overall or for specific aspects (time and cost of travel; rules and regulations; individual counseling; group counseling; drug education; medication). Among participants who stayed in treatment through 3 months, IOP participants reported an average overall burden rating of 14.51 (SD=22.65) during the most recent month of treatment, whereas OP participants rated their burden as significantly lower during this time, at 8.64 (SD=15.42) on the 1–100 scale (independent samples t-test=−2.12; p< .05).

Dosing

The modal maintenance dose was 16 mg, while the average dose dispensed (including induction doses) was 12.9 mg. The induction period was typically rapid, with 80% reaching a maintenance dose within 4 days. IOP and OP conditions did not differ significantly in average buprenorphine dose (13.0 vs. 12.8, p=.64).

Treatment Satisfaction

At 3-month follow-up, the vast majority of participants reported being either somewhat or very satisfied with the treatment they received at the program (87.1%). The high level of satisfaction was also observed when asked at the 6-month follow-up point (89.0% either somewhat or very satisfied). The differences between IOP and OP groups in patient satisfaction were non-significant (p=.36 at 3 months; .77 at 6 months).

3.2. Participant Outcomes

IOP vs. OP

Table 2 shows the results of the statistical analyses for 20 different outcome variables. For each outcome, the model-predicted values at each time point are shown for OP and IOP groups. The Condition X Time interaction tests the effect of IOP level treatment relative to OP level treatment with respect to change over time in the two conditions. Additionally, the test of the Time Effect gauges the significance of the overall change from baseline for both groups. No statistically significant differences were found between OP and IOP conditions for any of the outcomes examined (all ps>.05). Treatment retention rates, initially the conceptual underpinning for the expectation of between group differences, were virtually identical for OP and IOP groups at 3 month (72.9% vs. 72.4%) and 6 month (58.7% vs. 56.6%) follow-ups.

Table 2.

Outcomes for participants in standard outpatient (OP) and intensive outpatient (IOP) conditions.

| OP (n = 155) | IOP (n=145) | Condition x Time Interaction Test (OP v. IOP Effect) | Time Effect Test (Overall Change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Opioid dependence criteria, % (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 93.5 (.02) | 94.5 (.02) | χ2(2) = .81; p = .67 | χ2(2) = 248.71; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 18.1 (.03) | 23.4 (.04) | ||

| 6-months | 20.5 (.03) | 21.0 (.04) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Cocaine dependence criteria, % (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 36.1 (.04) | 44.8 (.04) | χ2(2) = .93; p = .63 | χ2(2) = 110.25; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 9.3 (.02) | 13.1 (.03) | ||

| 6-months | 11.1 (.03) | 11.3 (.03) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Opioid-positive urine test, % (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 72.3 (.04) | 70.7 (.04) | χ2(2) = .44; p = .80 | χ2(2) = 48.84; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 48.8 (.04) | 44.1 (.04) | ||

| 6-months | 55.8 (.04) | 48.9 (.04) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Cocaine-positive urine test, % (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 43.2 (.04) | 55.3 (.04) | χ2(2) = 5.37; p = .07 | χ2(2) = 16.24; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 35.5 (.04) | 38.8 (.04) | ||

| 6-months | 41.5 (.04) | 38.5 (.04) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Days of heroin use/last 30 days, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 22.3 (.78) | 22.3 (.79) | χ2(2) = .67; p = .72 | χ2(2) = 265.75; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 3.3 (.66) | 2.8 (.55) | ||

| 6-months | 3.9 (.69) | 3.2 (.65) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Days of cocaine use/last 30 days, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 7.3 (.89) | 7.1 (.83) | χ2(2) = .02; p = .99 | χ2(2) = 86.80; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 2.3 (.49) | 2.3 (.51) | ||

| 6-months | 2.0 (.43) | 2.0 (.47) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Days of crime/last 30 days, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 8.9 (.98) | 6.5 (.82) | χ2(2) = 3.99; p = .14 | χ2(2) = 89.46; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 1.2 (.40) | 1.9 (.51) | ||

| 6-months | 1.2 (.37) | 1.7 (.52) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Retention in treatment (time-to-dropout)

|

||||

| Days in treatment (max=180) | 127.1 | 126.9 | χ2(1) = .04; p=.84 | N/A |

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Medical, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .29 (.03) | .24 (.03) | χ2(2) = 1.45; p = .48 | χ2(2) = .09; p = .96 |

| 3-months | .27 (.03) | .28 (.03) | ||

| 6-months | .29 (.03) | .26 (.03) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Employment, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .86 (.02) | .83 (.02) | χ2(2) = .09; p = .95 | χ2(2) = 4.74; p = .09 |

| 3-months | .88 (.02) | .85 (.02) | ||

| 6-months | .87 (.02) | .83 (.02) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Alcohol, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .09 (.01) | .09 (.02) | χ2(2) = 1.69; p = .43 | χ2(2) = 31.33; p< .001 |

| 3-months | .04 (.01) | .04 (.01) | ||

| 6-months | .03 (.01) | .05 (.01) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Drug, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .29 (.01) | .30 (.01) | χ2(2) = .15; p = .93 | χ2(2) = 687.54; p< .001 |

| 3-months | .11 (.01) | .11 (.01) | ||

| 6-months | .10 (.01) | .10 (.01) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Legal, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .21 (.02) | .21 (.02) | χ2(2) = 2.80; p = .25 | χ2(2) = 91.40; p< .001 |

| 3-months | .07 (.01) | .11 (.02) | ||

| 6-months | .08 (.01) | .09 (.01) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Fam/Social, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .12 (.02) | .11 (.02) | χ2(2) = 1.00; p = .61 | χ2(2) = 5.44; p = .07 |

| 3-months | .10 (.02) | .12 (.02) | ||

| 6-months | .09 (.02) | .09 (.02) | ||

|

| ||||

|

ASI composite: Psychiatric, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | .20 (.02) | .20 (.02) | χ2(2) = 2.57; p = .28 | χ2(2) = 1.24; p = .54 |

| 3-months | .20 (.02) | .23 (.02) | ||

| 6-months | .20 (.02) | .21 (.02) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Quality of Life: Physical, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 58.66 (1.51) | 61.43 (1.51) | χ2(2) = 0.20; p = .91 | χ2(2) = 56.00; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 66.97 (1.66) | 68.77 (1.71) | ||

| 6-months | 65.43 (1.74) | 67.80 (1.74) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Quality of Life: Psychological, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 66.80 (1.49) | 68.24 (1.56) | χ2(2) = 3.48; p = .18 | χ2(2) = 41.49; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 74.42 (1.38) | 73.68 (1.49) | ||

| 6-months | 71.47 (1.48) | 74.00 (1.61) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Quality of Life: Social, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 62.80 (1.94) | 64.08 (1.83) | χ2(2) = 0.79; p = .68 | χ2(2) = 24.99; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 68.18 (1.84) | 67.33 (1.98) | ||

| 6-months | 71.04 (1.75) | 70.00 (1.92) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Quality of Life: Environmental, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 59.86 (1.42) | 60.84 (1.39) | χ2(2) = 0.03; p = .99 | χ2(2) = 27.99; p< .001 |

| 3-months | 64.14 (1.40) | 65.43 (1.50) | ||

| 6-months | 65.00 (1.45) | 66.06 (1.44) | ||

|

| ||||

|

HIV Risk Behaviors: Injection, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 1.06 (.28) | .41 (.14) | χ2(2) = 3.56; p = .17 | χ2(2) = 14.87; p< .001 |

| 3-months | .28 (.10) | .09 (.03) | ||

| 6-months | .18 (.07) | .10 (.03) | ||

|

| ||||

|

HIV Risk Behaviors: Sex, mean (SE)

|

||||

| Baseline | 3.10 (.19) | 3.29 (.18) | χ2(2) = 1.83; p = .40 | χ2(2) = 7.77; p = .02 |

| 3-months | 2.90 (.17) | 2.94 (.16) | ||

| 6-months | 2.91 (.16) | 2.76 (.16) | ||

SE = Standard Error

Opioid and Cocaine Dependence defined as meeting 3 or more criteria.

Overall Change

While there were no significant effects by Condition, participants in both groups experienced substantial improvement on nearly all of the outcomes. Reductions in opioid and cocaine use – whether measured by urine tests, self-report, or DSM-IV dependence symptoms – were of considerable magnitude and statistically significant (p<.001 for all six). Similarly, participants reported significantly fewer days of criminal activity (p<.001). These improvements also translated to elevations in quality of life, with significant improvement from baseline in physical, psychological, social, and environmental Quality of Life domain scores (p<.001 for each). There were significant decreases in the ASI composite scores for the alcohol, drug, and legal domains (p<.001 for all three). There were significant reductions in HIV risk behaviors for both injection risk (p<.001) and sex risk domains (p=.02). The only outcomes for which no significant overall time effects were observed were the ASI composite scores in the medical (p=.96), employment (p=.09), family/social (p=.07), and psychiatric domains (p=.54).

Relationship between Counseling Exposure and Outcome

In recognition of the possibility that participants’ exposure to counseling services may not have differed sufficiently between OP and IOP groups to register a condition effect, we examined the relationship between the same outcome measures and exposure to counseling services as a continuous variable, controlling for days in treatment. These analyses showed that change over time shown in these outcomes did not significantly differ as a function of counseling exposure for 17 of the 20 outcomes considered. Controlling for number of days in treatment, greater counseling exposure was associated with significantly less improvement for three outcomes – days of heroin use, days of cocaine use, and days of criminal activity (all ps<.01).

Cocaine Dependent Subsample

The main analysis was repeated in the subsample of 121 participants who met criteria for baseline cocaine dependence. No significant differences were found between IOP and OP in this subgroup for any outcome (all ps>.05).

4. DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial with 300 African Americans receiving buprenorphine treatment showed no significant differences between initiating treatment in OP and IOP levels of care for any of the 20 outcomes considered. Participants in both conditions showed statistically significant and clinically substantive improvements on 16 of these measures. Neither group showed statistically significant improvement on ASI composite scores for medical, psychiatric, employment, or family/social, indicating that the outpatient buprenorphine treatment coupled with drug abuse counseling did not sufficiently address these important co-occurring health and social problems.

Our original hypothesis that fewer participants would be retained in the IOP condition due to more strenuous compliance burdens was not supported. In fact, treatment retention rates at 3 and 6 months were virtually identical between the groups. In contrast to previous findings in methadone maintenance studies, where patients tended to complain about program rules and compulsory participation in counseling (Reisinger et al, 2009), the majority of participants in the current study were satisfied with the services received and generally perceived burden as low.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of observed differences between the two levels of psychosocial support in this study. One possibility is that the additional psychosocial services simply add little short-term benefit in conjunction with buprenorphine. Although we cannot fully endorse this explanation based on the data for the current study, several recent studies conducted in methadone (Gruber et al., 2008; Schwartz et al., 2011, 2012) and buprenorphine (Weiss et al., 2011) treatment settings point to this possibility. We believe a more likely explanation is that, despite differences in labeling of the two conditions and even differences (at least in Maryland) in the methods of reimbursement, the actual services delivered to these 300 participants were quite similar across the two conditions. Although there was a statistically significant difference in hours of counseling received in IOP and OP, the actual difference was less than we initially anticipated when designing the study and may be of minimal clinical significance.

The smaller-than-anticipated differences between the conditions in hours of counseling received can be attributed to at least two major factors: cultural and economic. Prior to adopting buprenorphine treatment, the participating clinics were centered on psychosocial counseling, and retained elements of this identity after transitioning to medication treatment. While the medication was seen as a useful adjunct to treatment, counseling was perceived as the active ingredient. Thus, clinics deliberately structured their OP level services to provide more weekly counseling than the minimum 2 hours stipulated by the ASAM PPC.

Economic factors worked in tandem with the cultural orientation of the clinics towards psychosocial counseling. In Maryland, the MCOs administering the substance abuse services for the state Medicaid program pay a bundled, daily “IOP rate” for a minimum of 2 hours of counseling per session (permitting no more than 4 IOP days per week) for up to 9 hours of counseling per week; in contrast, for OP, the same MCOs will authorize a certain number of sessions, group or individual, that can be utilized within a given time frame. In the two programs we studied, the net effect of these arrangements was that OP patients received substantially more counseling sessions than the two hours per week we had anticipated. On the other hand, IOP patients, on average, did not receive the full, minimum of 9 hours, because of lack of adherence to the full schedule of IOP activities and a reimbursement structure designed to support IOP but seemingly without the full financial alignment to achieve it.

We also considered the relationship between outcomes and hours of counseling received, and found a positive association between counseling exposure and frequency of heroin use, cocaine use, and criminal activity. This result is likely explained by the clinicians’ tendency to insist on participation in additional services for patients who were judged by staff to be stagnant in their progress. Thus, the observed association is likely not a causal one. Although negative results are difficult to interpret, these results suggest similar improvements on many measures for patients in both OP and IOP treatment. Group differences in terms of cocaine positive urines trended in favor of less cocaine use among IOP participants (p = .07), but overall between-group differences were not statistically significant. Likewise, in the cocaine dependent subsample, between-group differences were non-significant across all outcomes. Future studies regarding the impact of IOP and OP for cocaine dependent patients may be warranted, particularly in settings with greater differences in intensity between OP and IOP services than in the present study. Certainly, there may be other patient factors that might be related to treatment success; however, cocaine dependence quite likely stands as the single most important treatment entry patient characteristic that might influence treatment effectiveness.

This study also indirectly reflects the success story of buprenorphine expansion in Baltimore City, in which a number of formerly “drug-free” counseling programs were encouraged to adopt buprenorphine. This study was fielded at two such sites, providing important early data on patient outcomes in these settings. Many studies to date have focused on buprenorphine as delivered in primary care (Fiellin, 2007) or in Opioid Treatment Programs as an alternative to methadone (Koch et al., 2006). The overall improvements in drug use and functioning for patients at these two formerly drug-free clinics were substantial in both counseling conditions. Hence, the findings indirectly demonstrate the successful integration of buprenorphine treatment into these types of programs.

5. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. The findings may not generalize to other populations, clinics, or treatment systems. These generalizability concerns are balanced by the unique focus of the study on an underserved minority population that, following the Drug Abuse Treatment Act of 2000, was shown to have had limited access to buprenorphine treatment (WESTAT, 2006). The differences between OP and IOP conditions in hours of services received were statistically significant, but smaller than anticipated. Thus, the findings may not generalize to other clinics that have greater gulfs between OP and IOP level care. However, we felt it was important to conduct the study as an effectiveness, rather than as an efficacy trial; that is, examining IOP and OP as they were actually delivered in real-world clinical practice. The study demonstrates that, on the whole, the routine practice of starting patients in IOP does not yield better outcomes than starting patients in standard OP, at least for this population and in the way these levels of care were implemented in the study sites.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by RC1DA028407-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which did not play a role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

We thank that National Institute on Drug Abuse for funding the study, as well as the participating treatment programs for their clinical assistance: Total Health Care and Partners in Recovery. Finally, we thank Melissa Irwin for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Contributors

Drs. Mitchell, Schwartz, O’Grady, and Jaffe designed the Buprenorphine study. Drs. Mitchell and Schwartz managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Mr. Gryczynski undertook the statistical analysis, under the direction of Dr. O’Grady. Drs. Mitchell and Schwartz and Mr. Gryczynski wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised and edited by all authors. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Olsen was the BSAS Medical Director from 2009 to 2011. Dr. O’Grady has consulted with Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2000. text revised (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J, Maibach R, Thurlimann B, Sessa C, Aapro MS. Patients’ estimation of overall treatment burden: why not ask the obvious? J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:65–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Abraham AJ. State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA. The first three years of buprenorphine in the United States: experience to date and future directions. J Addict Med. 2007;1:62–67. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3180473c11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Sterling RC, Lundy A, Serota RD. A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness of intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;6:782–787. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber VA, Delucchi KL, Kielstein A, Batki SL. A randomized trial of 6-month methadone maintenance with standard or minimal counseling versus 21-day methadone detoxification. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe JH, O’Keeffe C. From morphine clinics to buprenorphine: regulating opioid agonist treatment of addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:S3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Early adoption of buprenorphine in substance abuse treatment centers: data from the private and public sectors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch AL, Arfken CL, Schuster CR. Characteristics of U.S. substance abuse treatment facilities adopting buprenorphine in its initial stage of availability. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Meyers K, Randall M, Durell J. “Intensive” outpatient substance abuse treatment: comparisons with “traditional” outpatient treatment. J Addict Disord. 1997;16:57–84. doi: 10.1300/J069v16n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Druley P, Navaline H, DePhilippis D, Stolley P, Abrutyn E. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger HS, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Peterson JA, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Marrari EA, Brown BS, Agar MH. Premature discharge from methadone treatment: patient perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2009;41:285–296. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2009.10400539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) Office of Applied Studies (OAS); Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D for the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Gandhi D, Jaffe JH. Interim methadone treatment compared to standard methadone treatment: 4-Month findings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;1:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Gandhi D, Jaffe JH. Randomized trial of standard methadone treatment compared to initiating methadone without counseling: 12-month findings. Addiction. 2012;107:943–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, Sonne SC, Ling W. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1238–1246. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESTAT. The SAMHSA evaluation of the impact of the DATA waiver program. 2006 Retrieved on June 26, 2012 from http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/FOR_FINAL_summaryreport_colorized.pdf.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) - Bref. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]