Abstract

Depressive symptoms are highly prevalent, underdiagnosed and undertreated in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH), and are associated with poorer health outcomes. This randomized controlled trial examined the effects of the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual self-care symptom management strategies compared to a nutrition manual on depressive symptoms in an international sample of PLWH. The sample consisted of a sub-group (N=222) of participants in a larger study symptom management study who reported depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms of the intervention (n=124) and control (n=98) groups were compared over three months: baseline, one-month and two-months. Use and effectiveness of specific strategies were examined. Depressive symptom frequency at baseline varied significantly by country (χ2 12.9; p=0.04). Within the intervention group there were significant differences across time in depressive symptom frequency [F(2, 207) = 3.27, p=0.05], intensity [F(2, 91) = 4.6, p=0.01] and impact [F(2, 252) = 2.92, p= 0.05), and these were significantly lower at one-month but not at two-months, suggesting that self-care strategies are effective in reducing depressive symptoms, however effects may be short-term. Most used and most effective self-care strategies were distraction techniques and prayer. This study suggests the people living with HIV can be taught and will employ self-care strategies for management of depressive symptoms, and that they are effective in reducing these symptoms. Self-care strategies are non-invasive, have no side-effects and can be readily taught as an adjunct to other forms of treatment. Studies are needed to identify the most effective self-care strategies and quantify optimum dose and frequency of use as a basis for evidence-based practice.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, HIV disease, self-management, symptom management, randomized controlled trial

Background

Depressive symptoms are the most common psychiatric diagnosis in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH), with an estimated prevalence two to ten times higher than in the general U.S. population (Bing et al., 2001; Pence, 2009). In international studies, there was a reported prevalence of depressive symptoms as high 58% in PLWH (Willard et al., 2009). In this population, even when controlling for access to care and antiretroviral medications, depressive symptoms are associated with poor medication adherence (Ammassari et al., 2004; Kacanek et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2007), risky behaviors including substance use and high-risk sexual practices (Bing et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2006; Ryan, Forehand, Solomon, & Miller, 2008), poorer virological response to treatment (Anastos, 2005; Hartzell, Spooner, Howard, Wegner, & Wortman, 2007) and increased risk of mortality (Anastos et al., 2005; Leserman, 2008). Prevalence of depressive symptoms for PLWH ranged from 37% to 56% in the U.S. and 57% to 98% in Puerto Rico (Asch et al., 2003; Eller, 2010; Toro, Burns, Pimentel, Peraza & Lugo, 2006). A review of mental health in PLWH in developing countries revealed depressive symptom prevalence in South Africa of 34.9% in men and women, and 63.3% in pregnant women (Collins, Holman, Freeman & Patel, 2006). Yet depressive symptoms are underdiagnosed and undertreated. In U.S. studies, up to 52% of depressed PLWH in care were not diagnosed or treated for depression (Asch et al., 2003; Leserman, 2008; Yun, Maravi, Kobayashi, Barton, & Davidson, 2005).

In a review of self-management of chronic illnesses, investigators reported that patient education and skills for self-management of their illness was beneficial both physically and psychologically. And, the use of written materials provided cost benefits over face-to-face education (Coster & Norman, 2009). In previous studies, we identified and validated self-care strategies used by PLWH to manage depressive symptoms, and created the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual (Eller et al., 2005; 2010). The purpose of this study was to test the efficacy of the strategies delineated in that manual for the management of depressive symptoms compared with a control condition, a nutrition manual. We assessed 1) the effect of the intervention on depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact, 2) number of users and frequency of use of specific self-care symptom management strategies, and 3) the degree to which participants judged specific self-care strategies to be effective.

Theoretical Framework

The intervention was based on the UCSF Symptom Management Conceptual Model (Dodd et al., 2001). Elements of the model in this study include a) the symptom experience (perceived depressive symptoms), b) symptom management strategies (self-care symptom management strategies in the Self-care Symptom Management Manual), and c) symptom outcomes (depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact).

Methods

This study is a sub-analysis of data from a multi-site randomized, controlled trial of the efficacy of the self-care HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual conducted by the International HIV/AIDS Nursing Research Network (Wantland et al., 2008). Employing a repeated-measures design, data were collected from two groups (experimental and control) at three time points over a three-month period: baseline, one-month, and two-months. All study sites received approval from human subjects review committees. A Data Safety and Monitoring Board was established by UCSF HIV Center. Certificates of Confidentiality were obtained as required. Informed consent was obtained from participants at baseline. Upon completion of the study, incentives, which varied by country ($3 to $20 US), were paid to participants.

Participants and Settings

Participants (N=222) were recruited during their routine visits to HIV clinics and community settings in South Africa, Puerto Rico and ten U.S. sites in six states. Included were HIV-positive adults with self-reported depression during the past week based on the Depressive Symptom Self-Report. Excluded were those with a documented diagnosis of dementia, unable to understand the consent procedure, or with prior experience using a self-care symptom management manual. Participants were randomly assigned to instruction in either the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual or a nutrition manual modified from the World Health Organization HIV/AIDS Nutrition Guide (World Health Organization, 2002). The sample included 124 intervention and 98 control subjects.

Measures

Both manuals and all study measures were available in English (U.S. and Africa) and Spanish (Puerto Rico). Instruments were forward translated into Spanish and back-translated into English to maintain content equivalence (Cha, Kim, & Earlen, 2007).

Demographic Data Survey

An investigator-developed survey was used to collect demographic data and clinical information. Included were age, gender, race, education, work, adequacy of income, current use of antiretroviral medications, AIDS diagnosis, use of antidepressant medications, years HIV+, viral load and CD4+ lymphocyte count.

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), was one of two scales used to measure depressive symptoms during the past week (Radloff, 1977). This scale was administered at baseline only. Responses on the 20-item scale range from 0 (never or rarely) to 3 (mostly or all of the time). Total score ranges from 0 to 60, and, as suggested by Radloff, scores ≥16 were used to indicate depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimate for the scale in this study was 0.91.

The Depressive Symptom Self-Report

This investigator-developed, single item, self-reported global measure of depressive symptoms in the past week, was administered at baseline, one-month and two-months. Respondents were instructed “Depression is feeling blue, low, depressed or sad. These feelings may also be associated with problems sleeping, weight loss, weight gain, or just a change in your appetite. You may also feel tired or fatigued.” Responses included a single “yes” or “no” if depressive symptoms were experienced in the past week. Scoring was dichotomous (1=yes; 0=no). Validity of measures of depressive symptoms was supported by significant association between CES-D scores and the Depressive Symptom Self-Report (r=.48; p <0.000).

Depressive Symptom Frequency, Intensity, Distress and Impact Scale

This scale measured depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact in participants who responded “yes” to the Depressive Symptom Self-Report. For frequency, participants were presented with a scale (1 to 7) and instructed “Circle the number of days that you have experienced depression this past week.” Depressive symptom intensity, distress and impact were each rated on a 1 to 10 scale with anchors “very low” (1) to “extremely high” (10). Validity was supported by significant associations between CES-D scores and depressive symptom frequency (r=.48; p <0.01), intensity (r=.57; p <0.01), distress (r=.52; p <.01;) and impact (r=.48; p <.01).

The Self-care Activities Checklist

Participants indicated which strategies they used from a list of self-care depressive symptom management strategies in the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual. They rated frequency of use and effectiveness of each strategy. Instructions stated “Here are some things people may do for depression. Please 1) Circle “yes” if you have tried it or do it now. Circle “no” if you never tried it. 2) If “yes,” how often do you do this? (daily/weekly/monthly), and 3) Does it work? (rated on a scale of 1=not very well to 10=very well).

Intervention and Control Conditions

Participants in the intervention group received the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual and were individually instructed in its use in one 30-minute session with the research nurse. The manual is divided into three sections. The “problem” section describes depressive symptoms. The “treatment” section describes common treatments for depressive symptoms and states “The first step is to contact your physician or nurse. If you feel like you might hurt yourself or others, seek help immediately (eg. by calling your local emergency number), or going to an emergency room.” The “self-care” section describes self-care strategies for depressive symptoms which, in previous studies, were reported by people living with HIV and were subsequently validated (Eller et al., 2005; Eller et al., 2010). If participants were unable to read, family and/or friends who could assist in using the manual were included in the training.

Participants in the control group received a nutrition manual titled “Nutritional Care and Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS,” and, to equalize attention and mask treatment assignment, the nutrition manual was reviewed individually in one 30-minute session with the research nurse.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (Version 19). Descriptive statistics were used to examine sample characteristics, symptom outcomes and self-care behaviors. ANOVAs with two group factors (intervention and control) and three time categories were conducted, with frequency, intensity, distress and impact of depressive symptoms as dependent variables. Where violations of homogeneity of variance occurred, the Brown-Forsythe F-ratio is reported. All tests were 2-tailed with α=.05 criterion for significance.

Analyses were conducted on a subset of 222 participants in a larger study who reported depressive symptoms in the past week. A priori power analysis was not possible. Post-hoc power analysis using G*Power 3 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) revealed small effect sizes and achieved power for depressive symptom frequency (ηp2=0.017, power = 39.8%), intensity (ηp2=0.038, power = 75.6%), distress (ηp2=0.011, power = 26.8%), and impact (ηp2=0.013, power = 31.2%).

Results

Participants

Baseline descriptive statistics and clinical indicators for intervention and control groups are presented in Table 1. There were no baseline between-group differences in these variables or in depressive symptom frequency, distress and impact. Depressive symptom intensity was higher in the intervention group (t= −2.1, df=116; p=.04).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical indicators of intervention and control groups

| Intervention (n=124) | Control (n=98) | |

|---|---|---|

| Range M (SD) |

Range M (SD) |

|

| Age | 22–70 | 22–66 |

| 42.7 (9.8) | 43.6 (9.4) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 49 (39.5) | 44 (44.9) |

| Male | 72 (58.1) | 54 (55.1) |

| Transgender | 3 (2.4) | 0 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 48 (38.7) | 27 (27.6) |

| Hispanic | 45 (36.3) | 32 (32.7) |

| White | 25 (20.2) | 27 (27.6) |

| Asian | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2.0) |

| Other | 4 (3.2) | 10 (10.2) |

| Education | ||

| < High School | 45 (36.3) | 21 (21.4) |

| High School | 43 (34.7) | 41 (41.8) |

| Technical/vocational school | 20 (16.1) | 27 (27.6) |

| College | 16 (12.9) | 9 (9.2) |

| Work for pay | ||

| Yes | 24 (19.4) | 26 (26.5) |

| No | 100 (80.6) | 72 (73.5) |

| Income | ||

| Adequate | 31 (25.0) | 19 (19.4) |

| Not Adequate | 93 (75.0) | 79 (78.6) |

| On ARV therapy | ||

| Yes | 88 (71.0) | 76 (77.6) |

| No | 36 (29.0) | 22 (22.4) |

| AIDS diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 56 (45.2) | 32 (32.7) |

| No | 65 (52.4) | 62 (63.3) |

| Don’t know | 3 (2.4) | 4 (4.1) |

| On antidepressant medications | ||

| Yes | 38 (30.6) | 39 (39.8) |

| No | 72 (58.1) | 54 (55.1) |

| No response/don’t know | 14 (11.3) | 5 (5.1) |

| Viral load undetectable | 40 (32.3) | 32 (32.7) |

|

Range M (SD) |

Range M (SD) |

|

| Years known HIV positive | <1–26 9.0 (6.0) |

<1–26 10.2 (6.5) |

| CD4 count (if known) | 0–1000 356 (245) |

0–1044 437 (264) |

There was a significant difference by country at baseline in depressive symptom frequency (χ2 12.9; p=.04); 40.8% of the Puerto Rico sample (40 out of 98 participants), 30.5% of the U.S. sample (170 out of 558 participants) and 10.1% of the Africa sample (12 out of 119 participants) reported depressive symptoms in the past week. There were no differences in depressive symptom intensity, distress or impact by country.

In the intervention group, dropout was 25.8% between baseline and one-month, and 53% between one-month and two-months. In the control group, dropout was 7% between baseline and one-month, and 42% between one-month and two-months. There were no significant differences in age, gender, race or site of data collection between dropouts and those remaining in the study in either group.

Effect of the intervention

There were no significant between-group differences in depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact over time (see Table 2)..

Table 2.

Self-reported depressive symptom frequency, intensity, impact and distress in the intervention and control groups over time

| Intervention Group | Baseline n=124 | One-Month n=92 | Two-Months n=43 |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Frequency | 5.5 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.3) | 5.7 (1.8) |

| Intensity | 7.9 (2.9) | 6.0 (3.7) | 7.4 (3.2) |

| Distress | 6.9 (2.7) | 6.2 (3.0) | 6.7 (2.8) |

| Impact | 7.1 (2.7) | 6.2 (3.1) | 7.1 (2.7) |

| Control Group | Baseline n=98 | Month One n=91 | Month Two n=53 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Frequency | 5.0 (2.2) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.2) |

| Intensity | 6.6 (3.6) | 7.6 (3.0) | 7.3 (3.4) |

| Distress | 6.3 (2.9) | 6.8 (2.7) | 7.0 (2.8) |

| Impact | 6.7 (3.0) | 7.2 (2.7) | 7.4 (2.9) |

Within the intervention group there were significant differences in depressive symptom frequency [F(2, 207) = 3.27, p=0.05], intensity [F(2, 91) = 4.6, p=0.01] and impact [F(2, 252) = 2.92, p= 0.05) across time. There were no differences in depressive symptom distress. Homogeneity of variance was violated for the variables “depressive symptom frequency” and “depressive symptom intensity” (Levene statistic <0.01). Therefore the Brown-Forsythe F-ratio was reported for these two variables.

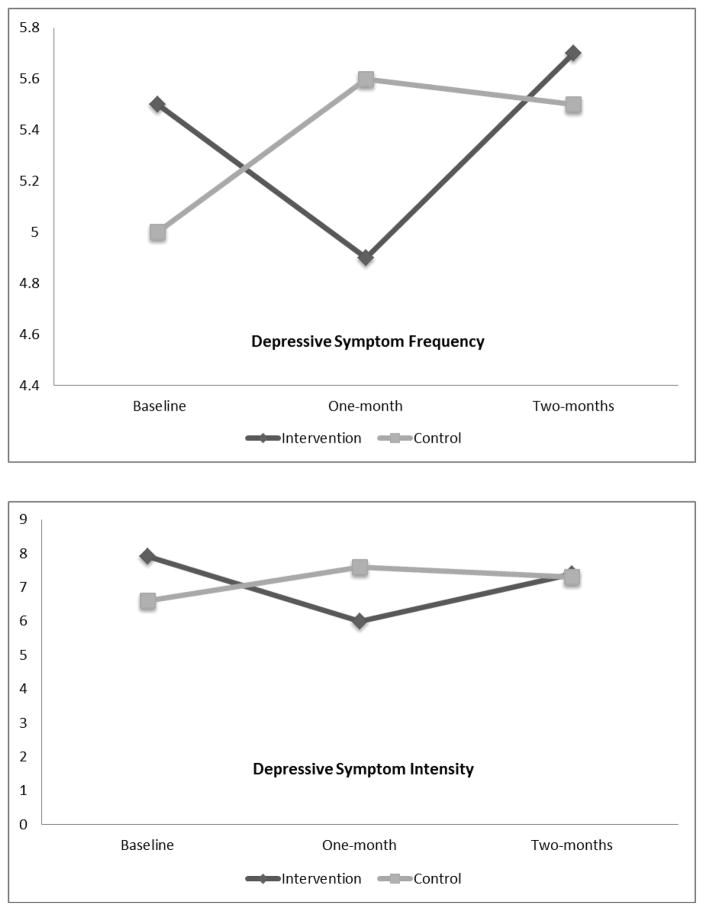

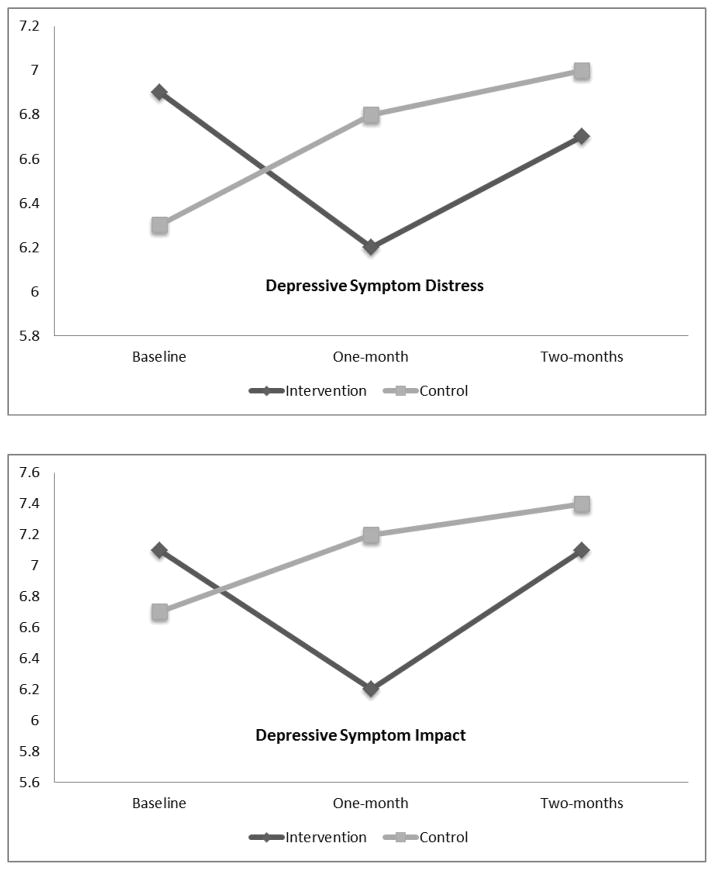

Post hoc multiple comparisons using the LSD criterion indicated that at one-month, compared to baseline, there were significantly lower scores in depressive symptom frequency (p=0.039), impact (p=0.021) and intensity (p=0.003). At two-months compared to one-month, there were significantly higher scores in depressive symptom frequency (p=0.039), and a trend for depressive symptom intensity and impact to increase back to baseline levels. The trend in depressive symptom distress demonstrated lower scores at one-month compared to baseline, and an increase back to baseline levels at two-months (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact over time for intervention (n=124) and control (n=98) groups

The control group had no significant within-group differences across time in depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress or impact. There was a trend toward an increase in all of these variables between baseline and one-month, and they remained elevated above baseline at month-two (see Figure 1).

Frequency of use and effectiveness of specific self-care symptom management strategies

Overall, at one-month, self-care strategies used by the most participants in the intervention group were “talking to family and friends,” “avoiding negative things” and “listening to music.” Strategies rated most effective were “reading” and “prayer.” Those used daily by the highest percentage of participants were “antidepressants,” “keeping busy” and “avoiding negative things” (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and percent of users, effectiveness rating and frequency of use of depressive symptom self-management strategies in the intervention group by time

| Strategies | One-Month (n=92) | One-Month Frequency of Use | Two-Months (n=43) | Two-Months Frequency of Use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users N (%) |

Effect (1–10) M (SD) |

D* N (%) |

W** N (%) |

M*** N (%) |

Users N (%) |

Effect (1–10) M (SD) |

D* N (%) |

W** N (%) |

M*** N (%) |

|

| Talking with Others | ||||||||||

| Family/friends | 60 (65%) | 7.3 (2.4) | 36 (60%) | 17 (28.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | 20 (47%) | 7.5 (2.0) | 14 (70%) | 5 (25%) | 1 (5%) |

| Health care provider | 48 (52%) | 7.5 (2.4) | 8 (16.7%) | 13 (27.1%) | 27 (56.3%) | 19 (44%) | 6.9 (2.4) | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (4.7%) | 13 (68.4%) |

| Others | 30 (33%) | 7.2 (2.6) | 15 (50%) | 6 (20%) | 9 (30%) | 13 (30%) | 6.6 (2.70) | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (15.4%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| Support group | 29 (32%) | 7.2 (2.5) | 6 (20.7%) | 14 (48.3%) | 9 (31%) | 15 (35%) | 7.3 (3.1) | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 6 (40%) |

| Complementary Strategies | ||||||||||

| Prayer | 45 (49%) | 7.9 (2.5) | 33 (73.3%) | 11 (24.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 19 (44%) | 8.4 (1.8) | 16 (84.2%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Meditation | 24 (26%) | 7.5 (2.5) | 15 (62.5%) | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (20.8%) | 11 (26%) | 6.9 (1.6) | 5 (45.5%) | 6 (54.5%) | 0 |

| Distraction Techniques | ||||||||||

| Listen to music | 54 (59%) | 7.7 (2.4) | 42 (77.8%) | 10 (18.5%) | 2 (3.7%) | 26 (60%) | 8.1 (2.1) | 22 (84.6%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0 |

| Keep busy | 51 (55%) | 7.5 (2.4) | 46 (90.2%) | 5 (9.8%) | 0 | 26 (60%) | 7.7 (2.1) | 21 (80%) | 5 (19.2%) | 0 |

| Treat self with food | 45 (49%) | 7.7 (2.1) | 21 (46.7%) | 14 (31.1%) | 10 (22.2%) | 18 (42%) | 7.3 (2.6) | 8 (44.4%) | 7 (38.9%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Read | 33 (36%) | 8.2 (1.8) | 26 (78.8%) | 7 (21.2%) | 0 | 16 (37%) | 6.8 (2.1) | 11 (68.8%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0 |

| Go to work | 16 (17%) | 7.4 (2.9) | 8 (50%) | 6 (37.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 10 (23%) | 7.2 (2.1) | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) |

| Draw | 11 (12%) | 6.9 (2.7) | 5 (45.5%) | 4 (36.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 6 (14%) | 6.8 (2.8) | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Physical Activity | ||||||||||

| Walk | 48 (52% ) | 7.2 (2.1) | 40 (83.3%) | 7 (14.6%) | 1 (2.1%) | 22 (51%) | 7.4 (2.7) | 16 (72.7%) | 5 (22.7%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Exercise | 30 (33%) | 7.4 (1.8) | 18 (60%) | 11 (36.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 12 (28%) | 7.5 (2.7) | 8 (66.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 |

| Medication | ||||||||||

| Antidepressants | 33 (36%) | 7.3 (2.4) | 31 (93.9%) | 2 (6.1%) | 0 | 16 (37%) | 6.9 (2.5) | 14 (87.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 |

| Denial/Avoidant Coping | ||||||||||

| Avoid negative things | 55 (60%) | 7.3 (2.4) | 47 (85.5%) | 6 (10.9%) | 2 (3.6%) | 25 (58%) | 7.3 (1.9) | 20 (80%) | 4 (16%0 | 1 (4%) |

| Cigarettes | 26 (28%) | 6.4 (3.1) | 20 (76.9%) | 5 (19.2%) | 1 (3.8%) | 13 (30%) | 5.8 (2.8) | 10 (76.9%) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Marijuana | 19 (21%) | 6.6 (3.1) | 10 (52.6%) | 6 (31.6%) | 3 (15.8%) | 11 (26%) | 6.6 (2.8) | 4 (36.4%) | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Alcohol | 16 (17%) | 6.1 (3.0) | 2 (12.5%) 10 (62.5%) | 4 (25%) | 12 (28%) | 6.3 (3.2) | 3 (25%) | 6 (50%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Street drugs | 10 (11%) | 6.7 (3.4) | 3 (30%) | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) | 3 (7%) | 5.3 (4.0) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 | 1 (33.3%) |

=Daily;

=Weekly;

=Monthly

At two-months, strategies used by the most participants in the intervention group were “listening to music,” “keeping busy” and “avoiding negative things.” Those rated most effective were “prayer” and “listening to music.” Those used daily by the highest percentage of participants were “antidepressants,” “listening to music” and “prayer” (See Table 3).

Additional findings

Participants in this study included those who, at baseline, self-reported depressive symptoms in the past week. An unanticipated finding was the difference in the number of participants who self-reported depressive symptoms and those who screened positive for depressive symptoms based on CES-D scores ≥16. While 222 participants self-reported depressive symptoms, 494 participants had CES-D scores ≥16. Additionally, 47 of the 222 participants who self-reported depressive symptoms in the past week did not screen positive for depression on the CES-D; and only 175 of those with CES-D scores ≥16 self-reported experiencing depressive symptoms. The prevalence of antidepressant use was low for both those with CES-D scores ≥16 (21.7%) and those self-reporting depressive symptoms (34.6%).

Limitations

Limitations of this study include self-report of depressive symptoms and high attrition rates. Sample sizes in the Puerto Rico and Africa samples limited data analysis by country. The inability to control the number of participants enrolled in this secondary analysis resulted in a lack of power to detect a between-subjects effect of the intervention.

Discussion

Depressive symptoms are highly prevalent, underdiagnosed and undertreated in PLWH, and are associated with risky behaviors, non-adherence, immune dysregulation and poorer health outcomes. We tested the efficacy of the HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual, compared to an attention control nutrition manual, for self-management of depressive symptoms. We also examined frequency of use and effectiveness of specific symptom management strategies.

There was insufficient power in this study to detect between-group effects. Attrition was high and sample size may have compromised the ability to detect these effects. It may be that those who dropped out of our study either no longer were experiencing depressive symptoms, or were too depressed to continue participation. In future studies, effective retention strategies and oversampling to compensate for attrition should be implemented, and reasons for dropout assessed.

The lack of significant between-group effects may have also been due to the study’s length. Three months may have been insufficient time for a larger effect to occur. Future studies with a longer treatment time are needed to assess the potential effects of this symptom management intervention.

Within the treatment group at one-month, depressive symptom frequency, intensity, distress and impact were reduced. At two-months, they increased to near baseline levels. These findings support the effectiveness of self-management strategies for reducing depressive symptoms in the short-term. The increases at two-months may be due to loss of effectiveness or a reduction in participants’ frequency of use of the strategies over time, resulting in an insufficient dose. Or, it may be due to differences in strategies employed. For example, one strategy used by the most participants at one-month but not at two-months was “talking to family and friends.” This may be an effective strategy, as emotional support was associated with lower levels of depression in PLWH (Deichert, Fekete, Boarts, Druley & Delahanty, 2008; Mello, Segurado & Malbergier, 2010).

The degree to which participants judged specific self-care strategies to be effective were similar at one-month and two-months. Although antidepressant medications were listed as one of the most frequently used strategies (daily), they were not rated as one of the most effective strategies. This is supported by a meta-analysis questioning the effectiveness of antidepressants (Pigott, Leventhal, Alter & Boren, 2010).

Distraction techniques were rated most effective and most frequently used. These findings are supported by Response Styles Theory (RST), which posits that distracting responses to depressive symptoms reduce the intensity of these symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). In an intervention study, Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow (1993) found that focusing on distracting responses shortened depressed mood.

We observed a discrepancy in results of the CES-D and single-item self-report of depressive symptoms at baseline. Both measured depressive symptoms the previous week, and should have produced comparable results. However 64.6% of those screening positive on the CES-D did not self-report depressive symptoms. It has been suggested that the CES-D overestimates depressive symptoms in PLWH due to its inclusion of somatic symptoms which commonly occur due to HIV disease or the side effects of antiretroviral medications (Kalichman, Rompa, & Cage, 2000; Shacham, Nurutdinova, Satyanarayana, Stamm, & Overton, 2009). It is also possible that participants did not report these symptoms due to fear of depression-related stigma, as reported by Roeloffs et al. (2003).

We also observed that 21% of those who did self-report depressive symptoms did not screen positive on the CES-D. It is possible that these respondents incorrectly attributed their symptoms to depression. These findings again call into question the performance of the CES-D in PLWH. The only study we could locate that examined the sensitivity and specificity of the CES-D in PLWH was conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. Sensitivity of the scale was 79% and specificity was 61% (Myer et al., 2008). Further studies of methods of assessment of depression in PLWH are needed, including an examination of the sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value of the CES-D by comparing the scale with a structured diagnostic inventory.

Whether assessed by screening or self-report, depression was undertreated in this sample, with approximately one-third or less receiving treatment. Adequate assessment and treatment of depression are critical to improving overall health outcomes in PLWH. Routine screening for depression in this population has been recommended for nearly a decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003). The World Health Organization (2008) recommended the integration of mental health interventions into HIV/AIDS programs and produced training materials for its assessment and management. Pyne et al. (2008) published a list of recommended quality indicators for depression care in PLWH that include targeted depression screening and use of antidepressants. This study suggests the people living with HIV can be taught and will employ self-care strategies for management of depressive symptoms, and that they are effective in reducing these symptoms. Self-care strategies are non-invasive, have no side-effects and can be readily taught as an adjunct to other forms of treatment. Studies are needed to identify the most effective self-care strategies and quantify optimum dose and frequency of use as a basis for evidence-based practice.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131; NIH/NINR T32NR007081 (HIV/AIDS Nursing Care and Prevention); Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Clinic & CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024989; Academic Research Enhancement Award, NIH 1R15NR011130; International Pilot Award, University of Washington Center for AIDS Research; University of British Columbia School of Nursing Helen Shore Fund; A Small Project Grant from the Duke University School of Nursing Office of Research Affairs; A faculty grant from the MGH Institute for Health Professions. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or any other funders.

References

- Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli, Starace F. Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:394–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastos K, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, Minkoff H, Greenblatt RM, Feldman J, Cohen M. The association of race, sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics with response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39:537–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch SM, Kilbourne AM, Gifford AL, Burnham MA, Turner B, Shapiro MF HCSUS Consortium. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: who are we missing? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:450–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam A, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Lescano C, Houck C, Zeidman J, Pugatch D Project SHIELD Study Group. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:444.e1–444.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV: Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV sMedicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha ES, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58:386–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS. 2006;20:1571–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster S, Norman I. Cochrane reviews of educational and self-management interventions to guide nursing practice: A review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:508–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deichert NT, Fekete EM, Boarts JM, Druley JA, Delahanty DL. Emotional Support and Affect: Associations with Health Behaviors and Active Coping Efforts in Men Living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:139–145. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, Faucett J, Froelicher ES, Humphreys J, Taylor D. Advancing the Science of Symptom Management. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33:668–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller LS, Bunch E, Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Reynolds NR, Nokes KM, Tsai YF. Prevalence, correlates and self-management of HIV-related depressive symptoms. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1159–1170. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller LS, Corless IB, Bunch EH, Kemppainen J, Holzemer W, Nokes K, Nicholas P. Self-care strategies for depressive symptoms in people with HIV disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;51:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell JD, Spooner K, Howard R, Wegner S, Wortmann G. Race and mental health diagnosis are risk factors for highly active antiretroviral therapy failure in a military cohort despite equal access to care. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;44:411–416. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacanek D, Jacobson DL, Spiegelman D, Wanke C, Isaac R, Wilson IB. Incident depression symptoms are associated with poorer HAART adherence: A longitudinal analysis from the Nutrition for Healthy Living study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53:266–272. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b720e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIVAIDS. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2000;188:662–670. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Palepu A, Cheng DM, Libman H, Saitz R, Samet JH. Factors associated with discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. AIDS Care. 2007;19:1039–47. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:539–45. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello VA, Segurado AA, Malbergier A. Depression in women living with HIV: clinical and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2010;13:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Smit J, Le Roux L, Parker S, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Common Mental Disorders among HIV-Infected Individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, Predictors, and Validation of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition and Emotion. 1993;7:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW. The impact of mental health and traumatic life experiences on antiretroviral treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009;63:636–640. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott HE, Leventhal AM, Alter GS, Boren JJ. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: Current status of research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2010;79:267–279. doi: 10.1159/000318293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne JM, Asch SM, Lincourt K, Kilbourne AM, Bowman C, Atkinson H, Gifford A. Quality indicators for depression care in HIV patients. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1075–1083. doi: 10.1080/09540120701796884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roeloffs C, Sherbourne C, Unutzer J, Fink A, Tang L, Wells KB. Stigma and depression among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2003;2595:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K, Forehand R, Solomon S, Miller C. Depressive symptoms as a link between barriers to care and sexual risk behavior of HIV-infected individuals living in non-urban areas. AIDS Care. 2008;20:331–336. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham E, Nurutdinova D, Satyanarayana V, Stamm K, Overton ET. Routine screening for depression: Identifying a challenge for successful HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23:949–955. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro GA, Burns P, Pimentel D, Peraza LRS, Lugo CR. Using a Multisectoral Approach to Assess HIV/AIDS Services in the Western Region of Puerto Rico. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:995–1000. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wantland DJ, Holzemer WL, Moezzi S, Willard SS, Arudo J, Kirksey KM, Huang E. A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of an HIV/AIDS Symptom Management Manual. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;36:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard S, Holzemer WL, Wantland DJ, Cuca YP, Kirksey KM, Portillo CJ, Lindgren T. Does “asymptomatic” mean without symptoms for those living with HIV infection? AIDS Care. 2009;21:322–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120802183511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Living well with HIV/AIDS: A manual on nutritional care and support for people living with HIV/AIDS. Rome: WHO/FAO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Executive Board. HIV/AIDS and Mental Health: Report by the Secretariat (EB124/6) 2008 Nov 20; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB124/B124_6-en.pdf.

- Yun LWH, Maravi M, Kobayashi JS, Barton PL, Davidson AJ. Antidepressant treatment improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy among depressed HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38:432–438. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000147524.19122.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]