Background: The regulatory mechanism of TOPK underlying cancer cell survival remains unknown.

Results: TOPK directly interacts with and phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32.

Conclusion: TOPK is a critical mediator of cervical cancer chemoresistance in response to doxorubicin.

Significance: This study provides new insight on role of TOPK in cervical cancer cell survival in response to doxorubicin.

Keywords: Cancer Therapy, Carcinogenesis, Caspase, Cell Death, Cell Growth

Abstract

T-lymphokine-activated killer cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) is known to be up-regulated in cancer cells and appears to contribute to cancer cell proliferation and survival. However, the molecular mechanism by which TOPK regulates cancer cell survival still remains elusive. Here we show that TOPK directly interacted with and phosphorylated IκBα at Ser-32, leading to p65 nuclear translocation and NF-κB activation. We also revealed that doxorubicin promoted the interaction between nonphosphorylated or phosphorylated TOPK and IκBα and that TOPK-mediated IκBα phosphorylation was enhanced in response to doxorubicin. Also, exogenously overexpressed TOPK augmented transcriptional activity driven by either NF-κB or inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 (cIAP2) promoters. On the other hand, NF-κB activity including IκBα phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation, as well as cIAP2 gene expression, was markedly diminished in TOPK knockdown HeLa cervical cancer cells. Moreover, doxorubicin-mediated apoptosis was noticeably increased in TOPK knockdown HeLa cells, compared with control cells, which resulted from caspase-dependent signaling pathways. These results demonstrate that TOPK is a molecular target of doxorubicin and mediates doxorubicin chemoresistance of HeLa cells, suggesting a novel mechanism for TOPK barrier of doxorubicin-mediated cervical cancer cell apoptosis.

Introduction

Doxorubicin, anthracycline antibiotic, is known to function as a potent chemotherapeutic agent against solid tumors and malignant hematological diseases (1, 2). Doxorubicin acts as DNA intercalating agent, causing dysfunction of DNA topoisomerase II and double-stranded DNA break, and elicits its inhibitory activity on tumors (3). This doxorubicin-induced DNA damage leads to target cell death. In parallel, DNA damage results in NF-κB activation to enhance transcription of NF-κB-driven genes, which are involved in cell proliferation and survival (4). In an unstimulated state, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to IκB. In response to doxorubicin, IκB kinases (IKKs)3 complex comprised of IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO is activated, and phosphorylates IκB, which is sequentially ubiquitinated and subjected to proteasomal degradation (5). NF-κB is then released from IκB, and activated NF-κB enters into nucleus and induces target gene transcription. Previous studies show that doxorubicin-induced apoptosis is triggered by cascades of caspase activation (6, 7). NF-κB is shown to play an important role in maintaining resistance to doxorubicin-induced tumor cells apoptosis and to contribute to prevention of efficacy of cancer therapeutics (8, 9). Indeed, inhibition of NF-κB sensitizes tumor cells to apoptosis in response to doxorubicin (10, 11).

T-LAK-cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) is known to be a serine/threonine kinase that is highly expressed in various malignant cells such as Burkitt's lymphoma and hematopoietic neoplasms or in normal tissues including testis, kidney, lung, placenta, and embryonic tissues (12–16). It has been proposed that TOPK, MAPKK-like protein kinase, acts as an upstream kinase for p38 MAPK, phosphatase MKP1, and peroxiredoxin 1 (12, 17, 18). In addition, TOPK phosphorylates JNK1 in UVB-mediated signaling or Ras-induced cell transformation and positively regulates ERK2 during tumorigenesis (19, 20). The cyclin B1/Cdk1 binds and phosphorylates TOPK on residue Thr-9 during mitosis, leading to enhancement of cytokinesis through PRC1 phosphorylation (13, 21). It was reported that TOPK associates with p53 and suppresses its transcriptional activity, resulting in reduction of p21 expression (22). Previously, we showed that TOPK confers TRAIL resistance to cancer cells (23). These reports suggest a role for TOPK in cancer cell proliferation and survival. However, little is known about mechanisms regarding the role of TOPK in cancer cell survival against cancer chemotherapy drugs involving doxorubicin.

Here we reveal that TOPK is a novel target molecule in response to doxorubicin and that TOPK directly interacts with and phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32, leading to subsequent NF-κB activation. We also demonstrate that depletion of endogenous TOPK abrogated doxorubicin-induced IκBα phosphorylation or p65 nuclear translocation. We provide evidence that overexpressed TOPK up-regulated expression of cIAP2 gene, one of the NF-κB-dependent antiapoptotic genes, and conferred resistance to doxorubicin-induced HeLa cervical cancer cell death.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Reagents

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells, CHO-K1, and human HeLa cervical cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Each cell line was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mm l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Doxorubicin hydrochloride, wedelolactone, SB202190, SP600125, U0126, and β-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma. The DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL system and luciferase assay system were from Promega (Madison, WI). Tubulin or IκBα antibody or protein A/G plus-agarose bead was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). V5 antibody or SuperScript III reverse transcriptase was from Invitrogen, respectively. Antibodies against caspase 3, caspase 8, cleaved PARP (Asp-214), p-AKT (Ser-473), p65, IκBα (Sepharose bead conjugate), and p-IκBα (Ser-32) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Antibody against TOPK or phosphoserine/threonine was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Active or inactive GST-TOPK protein was from Sigma or SignalChem (Richmond, Canada), respectively. Transfection reagent Effectene was from Qiagen. Z-VAD-FMK, Z-IETD-FMK, or GST-IκBα protein was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Glutathione-Sepharose 4B was from GE Healthcare Biosciences.

Plasmids and Transfection

Plasmid V5-TOPK was constructed. Briefly, total RNA from HeLa cell was extracted, and cDNA was prepared using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Sequentially, PCR was performed with the cDNA using sense strand, 5′-CGCGGATCCCGATGGAAGGGATCAGTAATTT-3′ harboring the BamHI site and antisense strand 5′-CCGCTCGAGCGGGACATCTGTTTCCAGAGCTT-3′ harboring the XhoI site, and the PCR product cut with BamHI/XhoI was inserted into the BamHI/XhoI sites of pcDNA6/V5-His A (Invitrogen). The construct was verified by sequencing. Plasmids, cIAP2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter vectors, wild type, and NF-κB mutants, were kindly provided by Dr. Hinrich Gronemeyer (24). GFP-p65/RelA construct was a kind gift from Dr. Warner C. Greene (25). NF-κB-dependent luciferase vector and TOPK siRNA construct were as described previously (23). 293 or HeLa cells growing on a 100-mm dish was transfected with each 10 μg of plasmids using Effectene according to the manufacturer's instructions. 24 h after transfection, the cells were lysed, and cell lysate was subjected to immunoblot or immunoprecipitation.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

In vitro kinase assay was performed with active or inactive TOPK and GST-IκBα protein. Briefly, the reactions containing 100 μm were done at 30 °C for 30 min. The samples were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblot. For TOPK immunoprecipitation kinase assay, 293 cells were transfected with V5-TOPK construct, treated with doxorubicin, and lysed. Cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with V5 antibody. The precipitates were reacted with GST-IκBα and analyzed with immunoblot using phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody.

Immunoblot and Immunoprecipitation

For immunoblot analysis, 20 μg of each total cell lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE, probed using each respective antibody, and detected with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and x-ray film. For immunoprecipitation, 500 μg of total cell lysate was mixed with specific antibody and then protein agarose beads at 4 °C for 2 h using rocker. The beads were washed, subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, and then subjected to immunoblot.

GST Pulldown Assay

To investigate the interaction of TOPK and IκBα, GST pulldown assay was performed with GST-IκBα. 293 cells were expressed with V5-TOPK construct, harvested 24 h after transfection, and lysed. 500 μg of total cell lysate was incubated with 2 μg of GST-IκBα protein coupled to glutathione-Sepharose 4B at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed with lysis buffer, boiled with sample buffer, separated on 10% SDS-PAGE, and then analyzed with immunoblot using V5 antibody.

Luciferase Assay

For luciferase assay, CHO-K1 cells growing on 6-well plates were transfected with each 1 μg of NF-κB promoter or cIAP2 promoter-luciferase reporter construct, plus 0.5 μg of the pRL-SV40 gene using 4 μl of Effectene reagent. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with doxorubicin for 24 h, harvested, and then lysed. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using cell lysate.

Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNAs were prepared from control siRNA cells or HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription-PCR was done using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and PCR master mix (Qiagen). PCR was carried out for 1 cycle at 95 °C for 15 min and 28 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min. Each primer is as follows: c-IAP2 (forward), 5′-CTTTGCCTGTGGTGGAAAAT-3′; c-IAP2 (reverse), 5′-ACTTGCAAGCTGCTCAGGAT-3′; GAPDH (forward), 5′-GACTCATGACCACAGTCCATGC-3′; and GAPDH (reverse), 5′-AGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTCTG-3′. PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and analyzed with GelDoc (Bio-Rad).

GFP-RelA Localization

Control siRNA cells or HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells were seeded on cover glass in 6-well plates and transfected with 0.5 μg of GFP-RelA construct. The cells were stimulated with doxorubicin for 6 h. The cells were observed under a fluorescent microscope to determine expression and localization of GFP-RelA.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl TUNEL Assay

TUNEL assay was performed using the DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Control siRNA cells or HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells were treated with doxorubicin for 24 h, fixed with 4% methanol-free formaldehyde, and permeabilized with Triton X-100. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase and nucleotide mixture including fluorescein-dUTP were used for labeling DNA breaks. After incubation, the cells were washed and mounted. The cells were observed and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical Analysis

The results are shown as the means ± S.D. for at least three independent experiments in duplicate. Significant differences were evaluated by Student's t test.

RESULTS

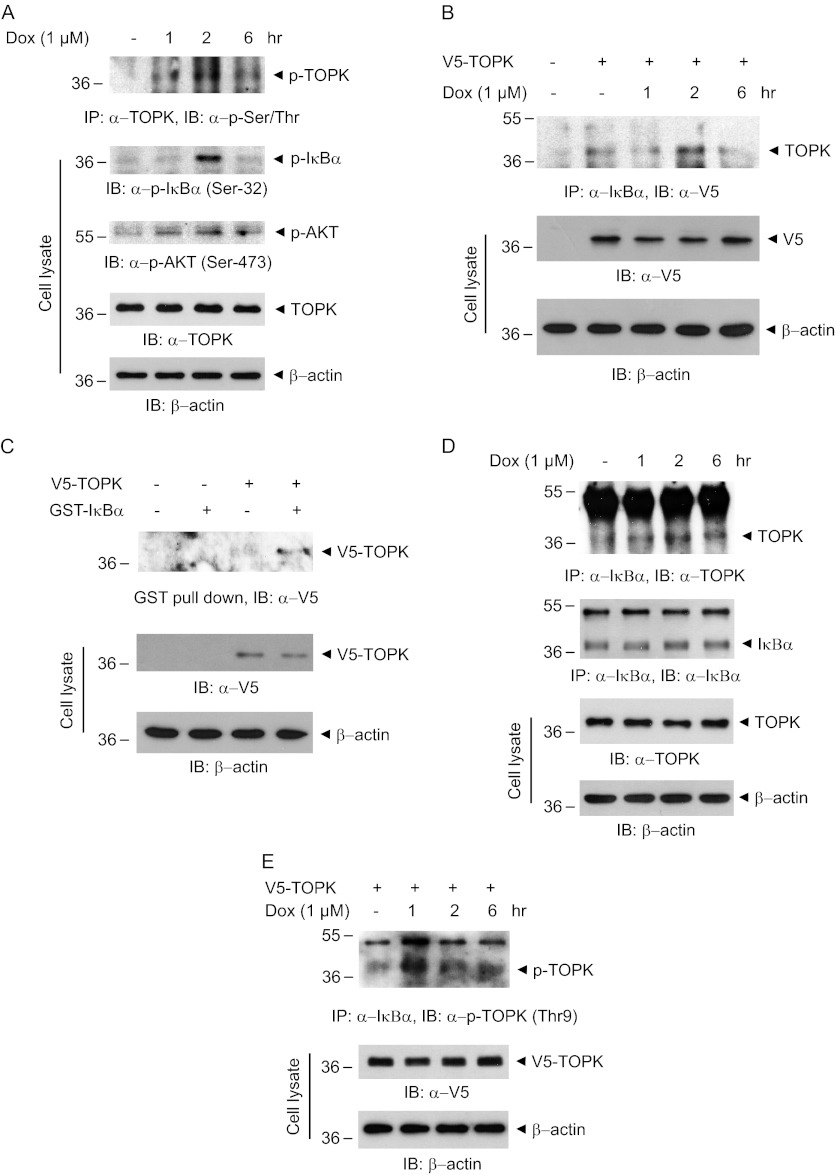

Doxorubicin Activates TOPK and Promotes Association of TOPK with IκBα

Little is known about signaling effectors of TOPK, including upstream kinases, downstream substrates, or stimuli. Doxorubicin commonly used in cancer treatment is known to induce genotoxic stress and p53 activation (26). However, the molecular targets of doxorubicin are poorly characterized. We have explored whether doxorubicin can affect TOPK activity or expression. To investigate whether doxorubicin might affect TOPK activity, we first treated human cervical HeLa cancer cells with doxorubicin in time-dependent manner. The results showed that doxorubicin strongly induced phosphorylation of Ser/Thr residues on TOPK, indicating the efficacy of doxorubicin on catalytic activity of TOPK (Fig. 1A). TOPK expression was slightly affected by doxorubicin treatment. We next examined the change of phosphorylation level of IκBα or AKT that is involved in cancer cell survival. Phosphorylation level of IκBα or AKT was augmented at 1 or 2 h after doxorubicin treatment. These results suggest that TOPK might be one of the molecular targets of doxorubicin and that doxorubicin-induced TOPK activity might be implicated in IκBα phosphorylation. We next hypothesized that TOPK could associate with and regulate IκBα phosphorylation status. To examine the possibility for binding of TOPK to IκBα, we transfected V5-TOPK into HEK293 cells, left them in the absence or presence of doxorubicin, and then performed immunoprecipitation experiments. We discovered that TOPK directly bound to IκBα in vivo, and doxorubicin markedly enhanced the binding capacity (Fig. 1B). To further verify that TOPK interacts with IκBα in vitro, GST pulldown assays were also carried out. GST-IκBα coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with cell lysate expressing V5-TOPK construct. The results indicated that TOPK bound to IκBα in vitro, proving a direct interaction between TOPK and IκBα (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we verified that endogenous TOPK associated with IκBα, and the interaction was significantly potentiated by doxorubicin treatment (Fig. 1D). To ensure that phosphorylated TOPK is indeed active form of TOPK, we also explored whether phosphorylated TOPK interacts with IκBα. The phosphorylated TOPK at Thr-9 was shown to bind to IκBα (Fig. 1E). The binding was markedly increased in response to doxorubicin. Collectively, these findings demonstrated that TOPK interacts with IκBα and that doxorubicin induces TOPK phosphorylation and promotes association of phosphorylated TOPK with IκBα, probably affecting IκBα phosphorylation.

FIGURE 1.

TOPK is activated by doxorubicin and directly associates with IκBα. A, HeLa cells were stimulated with 1 μm of doxorubicin (Dox) for each indicated time. Each cell lysate (500 μg) was immunoprecipitated (IP) with TOPK antibody (1 μg) and followed by immunoblotting (IB) using phosphoserine/threonine (p-Ser/Thr) antibody. Phosphorylation of the indicated proteins was detected with the respective phospho-specific antibodies. B, 293 cells grown on 100-mm dishes were transfected with each 10 μg of empty vector or V5-TOPK construct. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for each indicated time. Each cell lysate (500 μg) was subjected to immunoprecipitation using IκBα antibody (1 μg) and then analyzed by immunoblot using V5 antibody. Expression of V5-TOPK was verified. C, each 10 μg of empty vector or V5-TOPK construct was expressed in 293 cells, and the GST pulldown experiment was done using cell lysate (500 μg) and GST-IκBα (2 μg) coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads. The beads were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and then probed with V5 antibody. D, HeLa cells were treated with 1 μm of doxorubicin for the indicated times. Immunoprecipitation was done with IκBα antibody (Sepharose bead conjugate), followed by immunoblot using TOPK or IκBα antibody. E, each 10 μg of V5-TOPK construct was expressed in 293 cells. The cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for each indicated time. Each cell lysate (500 μg) was immunoprecipitated using IκBα antibody (Sepharose bead conjugate) and then probed with phospho-TOPK (Thr-9) antibody.

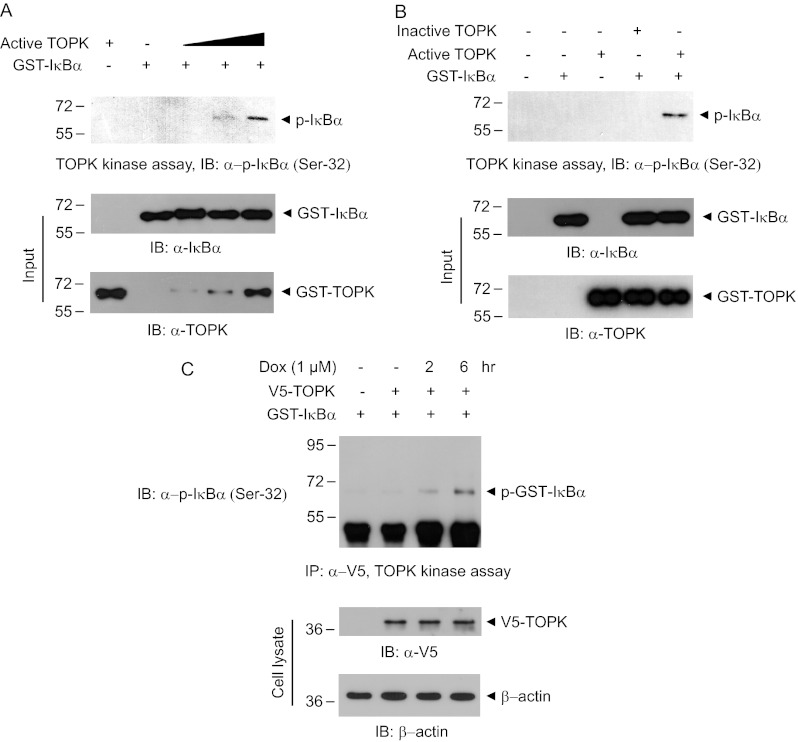

TOPK Directly Phosphorylates IκBα, and Doxorubicin Enhances Its Kinase Activity

We next examined whether TOPK could phosphorylates IκBα. The active form of TOPK, a constitutively phosphorylated TOPK at Thr-9, was employed for kinase assay. Kinase assay using active TOPK and GST-IκBα was performed in vitro. The results revealed that active TOPK phosphorylated residue Ser-32 on IκBα in dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). As expected, inactive TOPK did not exert the kinase activity against IκBα (Fig. 2B). We also investigated whether doxorubicin affects TOPK-induced IκBα phosphorylation in vivo. V5-TOPK construct was expressed in HEK293 cells, followed by immunoprecipitation kinase assay. We confirmed that doxorubicin strongly induces TOPK-mediated phosphorylation of IκBα (Ser-32) in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that TOPK associates with and directly phosphorylates IκBα to elicit NF-κB activity.

FIGURE 2.

TOPK phosphorylates IκBα at Ser-32. A, in vitro kinase assay was performed with GST-IκBα (0.5 μg) and each active TOPK (25, 50, and 100 ng). After 30 min of incubation at 30 °C, the reaction mixture was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) using phospho-IκBα (Ser-32) antibody. B, TOPK kinase assay was done using active or inactive TOPK (each 100 ng). The phosphorylated IκBα was detected with phospho-specific antibody recognizing Ser-32 residue on IκBα. C, 293 cells were transfected with V5-TOPK or empty vector. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with doxorubicin (Dox, 1 μm) for 2 or 4 h, and cell lysate was immunoprecipitated (IP) with V5 antibody. The immunoprecipitation kinase assay was performed using GST-IκBα (0.5 μg).

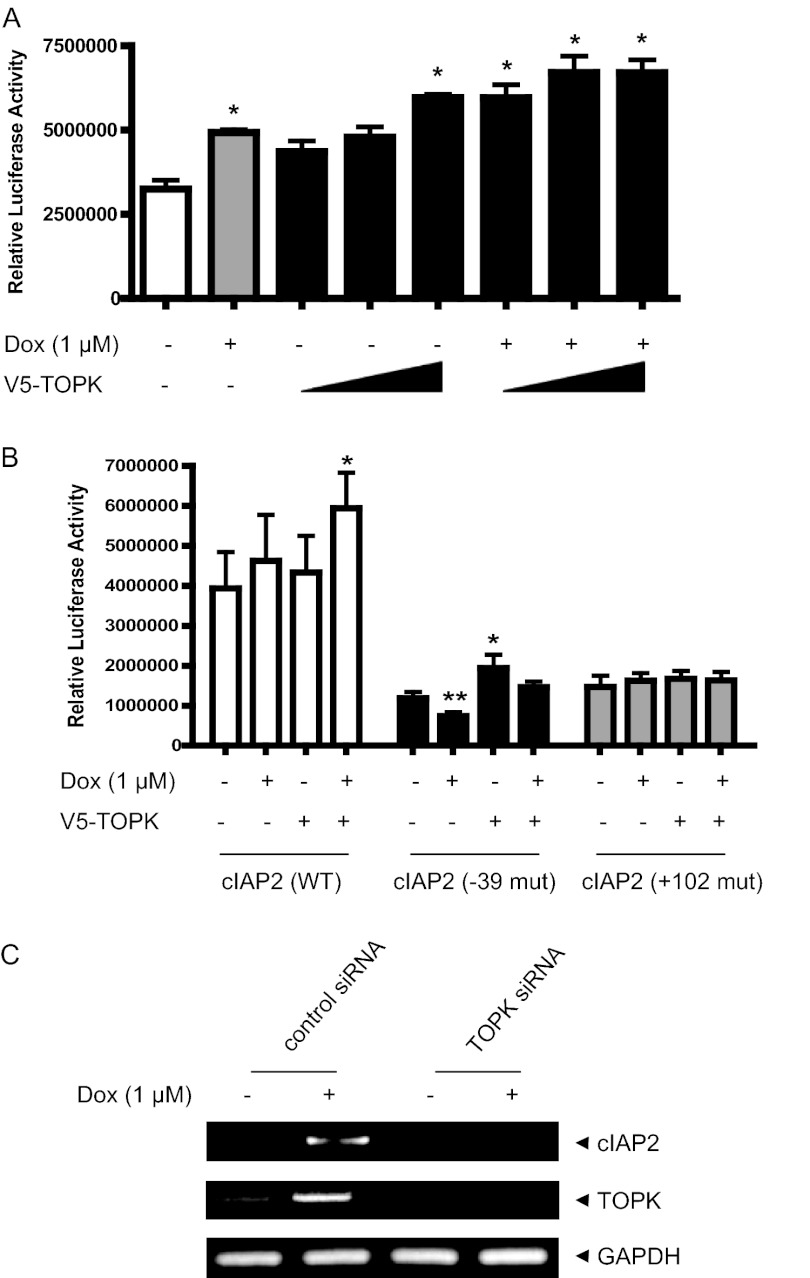

TOPK Positively Regulates NF-κB-driven Transcriptional Activity and cIAP2 Gene Expression in Response to Doxorubicin

Doxorubicin has been reported to induce NF-κB activation in apoptosis process (27). We asked whether TOPK can be involved in doxorubicin-induced NF-κB-responsive transcriptional activity. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with NF-κB promoter-driven luciferase reporter construct without or with the V5-TOPK construct and then left in absence or presence of doxorubicin. As expected, NF-κB promoter-driven transcriptional activity was augmented by doxorubicin treatment (Fig. 3A). Also, expression of TOPK alone increased the transcriptional activity in dose-dependent manner. Moreover, doxorubicin-induced NF-κB activity was markedly increased by TOPK expression. We next employed the promoter of the cIAP2 gene, one of NF-κB responsive genes, which is linked to luciferase reporter gene. Using promoters of wild type or NF-κB cis-element mutant types of cIAP2, transcriptional activities were assessed. As shown in Fig. 3B, TOPK expression resulted in an increase of cIAP2 promoter-driven luciferase activity induced by doxorubicin, whereas the activity was greatly reduced in cIAP2 promoters having a mutation on NF-κB cis-element. It appeared that cIAP2 promoter (−39 mut) having a mutation of a NF-κB site (−39) elicited a little differential responsiveness compared with another cIAP2 promoter (+102 mut), indicating site-specific selectivity of NF-κB response. We have previously established HeLa-TOPK siRNA knockdown cell lines (23). Using a reverse transcription-PCR experiment, we next investigated whether TOPK affects expression of cIAP2 gene in response to doxorubicin. Doxorubicin strongly induced expression of cIAP2 gene in control cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the doxorubicin-induced cIAP2 gene expression was dramatically diminished in TOPK siRNA cells. As expected, doxorubicin treatment also increased the expression of TOPK gene. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that TOPK up-regulates NF-κB activity and cIAP2 expression in response to doxorubicin, implying the role of TOPK in doxorubicin-mediated apoptotic signaling.

FIGURE 3.

TOPK promotes doxorubicin-induced NF-κB activity and cIAP2 transcriptional activity. A, CHO-K1 cells grown on 6-well plates were transfected with NF-κB-luciferase construct (1 μg) and each indicated V5-TOPK construct (1, 2, 4 μg), together with 0.1 μg of pRL-SV40 gene. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated or not treated with doxorubicin (Dox,1 μm) for 6 h. Luciferase activity was measured using cell lysate. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized against Renilla luciferase activity. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.05. B, CHO-K1 cells grown on 6-well plates were transfected with each WT or mutant (−39 and +102) cIAP2 promoter driven luciferase construct (1 μg) and V5-TOPK construct (1 μg), together with 0.1 μg of pRL-SV40 gene. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 6 h. Luciferase activity was evaluated. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.05. C, total RNAs were prepared from HeLa-TOPK siRNA or control siRNA cells stimulated with doxorubicin (1 μm). RT-PCR was sequentially performed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase and each primer for cIAP2 or GAPDH genes. PCR products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and analyzed using GelDoc (Bio-Rad).

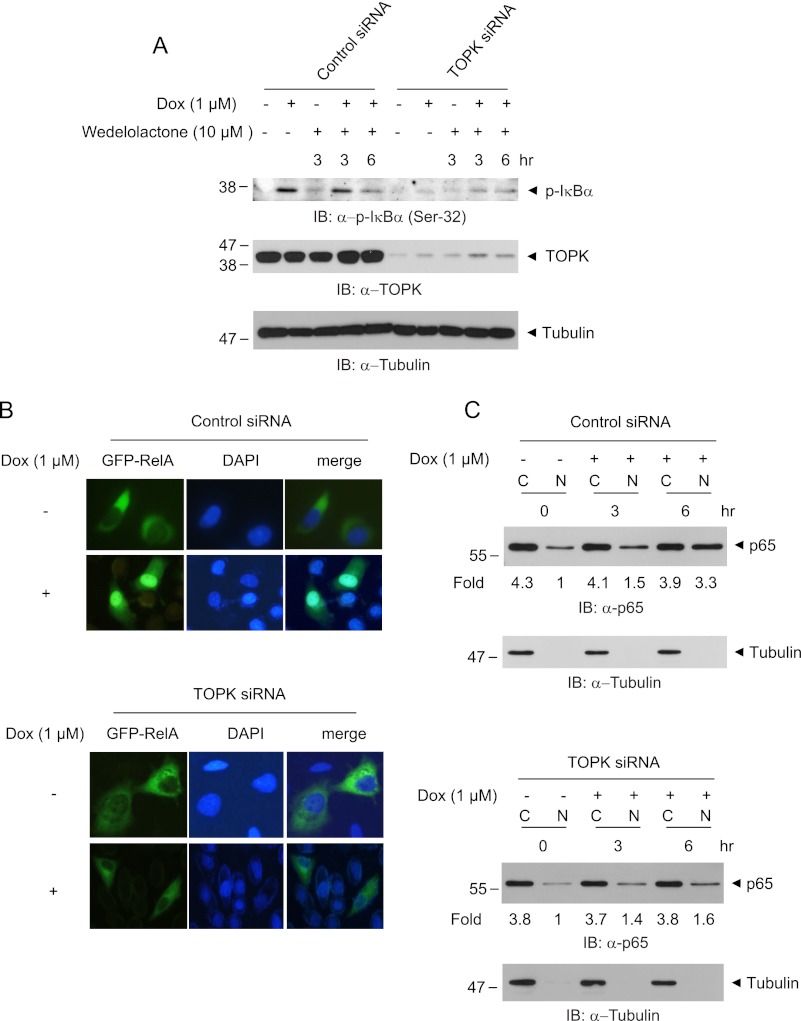

Depletion of TOPK Abolishes Doxorubicin-mediated IκBα Phosphorylation and p65 Nuclear Translocation

Doxorubicin has been suggested to induce IκB phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation (28). To clarify the effect of TOPK on doxorubicin-mediated IκBα degradation or phosphorylation, we employed HeLa-TOPK siRNA knockdown cell lines. As expected, the phosphorylation level of IκBα in HeLa cells expressing control siRNA was markedly augmented in response to doxorubicin treatment, whereas the level was little changed in TOPK siRNA cells (Fig. 4A). We also determined the effect of wedelolactone, the irreversible inhibitor of IKKα and IKKβ, on doxorubicin-induced IκBα phosphorylation. Wedelolactone little affected the doxorubicin-induced IκBα phosphorylation. These data imply that TOPK-mediated IκBα phosphorylation in response to doxorubicin might be independent on IKKs. In response to various stimuli including doxorubicin, p65/RelA nuclear translocation is essential for NF-κB activation. The cells were transfected with GFP-RelA construct, treated with doxorubicin, and then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. In control siRNA cells, RelA was shown to be successfully translocated to the nucleus in response to doxorubicin (Fig. 4B). In contrast, RelA failed to displace from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in TOPK siRNA cells by doxorubicin. Also, the level of RelA protein in the cytoplasm or nucleus was assessed. Nuclear RelA was markedly increased in response to doxorubicin in control siRNA cells (Fig. 4C), whereas the nuclear RelA was a little increased in TOPK siRNA cells. On the other hand, the basal level of nuclear RelA in the absence of doxorubicin is decreased in TOPK siRNA cells, compared with control siRNA cells, suggesting TOPK-mediated basal regulation of nuclear p65 expression. Collectively, these findings propose that TOPK mediates IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent RelA nuclear translocation in response to doxorubicin, as well as regulation of basal expression of nuclear p65.

FIGURE 4.

Ablation of TOPK blocks IκBα phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation in response to doxorubicin. A, HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells or control siRNA cells were treated with doxorubicin (Dox, 1 μm) for the indicated times in the presence or absence of wedelolactone (10 μm). Phosphorylated IκBα, TOPK, or tubulin proteins were assessed with the respective antibodies. B, TOPK siRNA cells or control siRNA cells grown on cover glass were transfected with GFP-RelA. At 24 h post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 6 h. Cells mounted on slide glass were observed with fluorescent microscope. The nuclei were stained with DAPI, and representative photos of at least three independent experiments are shown. C, TOPK siRNA cells or control siRNA cells were incubated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for indicated time. The cells were harvested, and cytoplasmic extract (lanes C) or nuclear extract (lanes N) was prepared. The p65 level was evaluated using immunoblot (IB) analysis. ImageJ software was used for quantification.

TOPK Confers Resistance to Doxorubicin-induced HeLa Cancer Cell Apoptosis

We next asked that TOPK might contribute to HeLa cervical cancer cell chemoresistance in response to doxorubicin. Therefore, we explored the effect of knocking down TOPK on doxorubicin-induced cell death. The doxorubicin-induced apoptosis rate in control siRNA cells was reduced ∼29%, compared with the rate in HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells (Fig. 5A). To examine whether endogenous TOPK affected doxorubicin-mediated caspases activation leading to PARP cleavage, activation of caspase 3 or caspase 8, as well as PARP were examined in TOPK siRNA or control siRNA cells. Cleaved forms of caspase 3 or caspase 8 were more increased by doxorubicin treatment in TOPK siRNA cells than control siRNA cells (Fig. 5B). Also, cleaved forms of PARP were more increased in TOPK siRNA cells. These results demonstrate that endogenous TOPK alleviates doxorubicin-induced caspase 8 and caspase 3 activation, leading to PARP inactivation, suggesting the role of TOPK in doxorubicin-induced HeLa cancer cells apoptosis. To ensure that doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells is mediated via caspase activation pathway, two inhibitors, general caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, and caspase 8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK, were employed. As expected, cleaved forms of PARP were decreased in the presence of each inhibitor, together with doxorubicin (Fig. 5C). These data show that doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in TOPK siRNA cells is mediated via caspase activation pathway. On the other hand, MAPK signaling pathways including ERK, p38, and JNK have been suggested to be implicated in doxorubicin-induced cancer cells apoptosis (29, 30). Therefore, we next asked whether MAPK pathways are involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells. Using specific inhibitors, such as MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190, and JNK inhibitor SP600125, the effect of doxorubicin on PARP cleavage in TOPK siRNA cells was determined. Treatment of SP600125, but not U0126 and SB202190, blocked doxorubicin-induced PARP cleavage (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that JNK might play an important role in doxorubicin-induced HeLa cells, especially TOPK-depleted cell killing.

FIGURE 5.

TOPK confers resistance to doxorubicin-mediated HeLa cancer cell apoptosis. A, HeLa-TOPK siRNA cells or control siRNA cells on cover glass were treated with doxorubicin (Dox, 1 μm) for 24 h. TUNEL assay was employed for apoptosis analysis. The cells were observed by immunofluorescence microscopy. The percentage of dead cells was estimated by calculating dead cells and live cells (300 cells minimum). Representative images of at least three independent experiments are shown. B, TOPK siRNA cells or control siRNA cells were incubated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 24 h. The levels of cleaved caspase 8, caspase 3, and PARP were indicated. C, TOPK siRNA cells were stimulated with doxorubicin (1 μm) in the presence or absence of each 20 μm of Z-VAD-FMK or Z-IETD-FMK. Cleaved PARP level was shown. D, TOPK siRNA cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) in the presence or absence of 10 μm each SB202190, SP600125, and U0126. The amount of cleaved PARP was indicated. IB, immunoblot; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

DISCUSSION

It has been suggested that some stimuli including TPA or UVB positively regulate TOPK activity (12, 17, 19). However, information about signaling pathways or stimuli triggering TOPK activation is still lacking. In this study, we uncovered that doxorubicin, one of the anticancer drugs, could phosphorylate serine or threonine residues on TOPK and increases TOPK mRNA level, indicating the effect of doxorubicin on TOPK catalytic activity and TOPK gene expression. Although the action mechanism of doxorubicin in cancer cell apoptosis is known, the molecular targets of doxorubicin are poorly identified. We demonstrate here that TOPK functions as a novel target molecule of doxorubicin, implying a critical role for TOPK in doxorubicin-induced cervical cancer cell death. Some molecules, such as p38 MAPK, JNK, phosphatase MKP1, and peroxiredoxin 1, have been proposed to act as downstream substrates for TOPK (12, 17–19). However, evidence for downstream targets of TOPK still remains elusive. We identified that TOPK directly binds to IκBα and phosphorylates serine-32 residue on IκBα in response to doxorubicin leading to NF-κB activation. These data define TOPK as an upstream kinase of IκBα regulating NF-κB activity with a possible role in doxorubicin-mediated cervical cancer cell apoptosis. It has been suggested that NF-κB contributes to chemoresistance to anticancer drugs and is triggered by genotoxic agents including doxorubicin, which limits the chemotherapeutics-mediated anticancer effects (31). Also, NF-κB activation is known to result in induction of survival factors, Bcl-2 or IAPs (32). Therapeutic approaches to overcome NF-κB-mediated chemoresistance are closely implicated in induction of IκB overexpression or IκB stabilization via proteasome inhibition preventing IκB degradation (33, 34). In this study, endogenously overexpressed TOPK was shown to increase doxorubicin-mediated NF-κB-driven transcriptional activity in HeLa cervical cancer cells. The findings that TOPK activates NF-κB in response to doxorubicin revealed the role of TOPK as a critical mediator in cervical cancer cell survival. A previous report proposed that NF-κB activity induced by ultraviolet radiation or chemotherapeutic agent-induced DNA damage might promote U2OS osteosarcoma cell death, associated with interaction of p65 and histone deacetylases (35). A recent study also showed that doxorubicin increased transcription of the cIAP2 gene, an antiapoptotic gene, but repressed expression of Bcl-xL, XIAP, Bcl-2, or survivin gene in U2OS osteosarcoma cells and that NF-κB inhibition prevented doxorubicin-mediated transcription of cIAP2, leading to enhanced cell death (27). Agreeing with this result, we indicated that expression of cIAP2 gene is increased in HeLa cervical cancer cells by doxorubicin treatment, but TOPK depletion abolishes this augmentation via NF-κB inhibition. These findings suggest that doxorubicin-mediated increment of cIAP2 gene transcripts might be dependent on endogenous TOPK expression and that the reduction of cIAP2 via NF-κB inhibition promotes cervical cancer cell death. It has been proposed that some MAPKs or their related signaling pathways are implicated in chemotherapeutics-mediated apoptosis (36–38). JNK activity is especially closely involved in apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic agents involving doxorubicin (7, 30, 39), which results in release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase to cytoplasm, leading to caspase activation. Procaspase-9 is recruited and activated with subsequent activation of the downstream effector caspase-3 and PARP (40). Inhibition of JNK, but not ERK and p38 MAPK, markedly prevents doxorubicin-mediated apoptosis of TOPK-depleted HeLa cervical cancer cells. This finding suggests that JNK activity is essential for apoptosis to doxorubicin in cervical cancer cell lacking endogenous TOPK. Therefore, an approach to efficient doxorubicin-mediated chemotherapy for cervical cancers might include in part JNK activation, as well as blockage of TOPK expression or activity. Taken together, this study demonstrates that doxorubicin activates TOPK interaction with IκBα and promotes its kinase activity against IκBα at Ser-32, leading to NF-κB activation. Also, we provide evidence that TOPK augments expression of cIAP2, acting as a key survival mediator in doxorubicin-mediated apoptotic pathway, conferring resistance to doxorubicin-induced HeLa cervical cancer cell death. We here suggest that TOPK is a critical mediator of cervical cancer chemoresistance in response to doxorubicin. Therefore, approaches to inhibit TOPK through blocking its expression or its kinase activity via development of pharmacologic inhibitor might be valuable for further investigation involving mechanistic research to overcome cervical cancer chemoresistance and enhance chemosensitization.

Acknowledgments

We thank laboratory members for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Grant 2010-0005899. This work was supported in part by Konyang University Myunggok Research Fund of 2009.

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- cIAP2

- inhibitor of apoptosis 2

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- TOPK

- T-lymphokine-activated killer cell-originated protein kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Christiansen S., Autschbach R. (2006) Doxorubicin in experimental and clinical heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 30, 611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henderson I. C., Frei T. E., 3rd (1979) Adriamycin and the heart. N. Engl. J. Med. 300, 310–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Binaschi M., Capranico G., Dal Bo L., Zunino F. (1997) Relationship between lethal effects and topoisomerase II-mediated double-stranded DNA breaks produced by anthracyclines with different sequence specificity. Mol. Pharmacol. 51, 1053–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCool K. W., Miyamoto S. (2012) DNA damage-dependent NF-κB activation. NEMO turns nuclear signaling inside out. Immunol. Rev. 246, 311–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin A., Karin M. (2003) NF-κB in cancer. A marked target. Semin. Cancer Biol. 13, 107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ehrhardt H., Wachter F., Maurer M., Stahnke K., Jeremias I. (2011) Important role of caspase-8 for chemosensitivity of ALL cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 7605–7613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manna S. K., Gangadharan C., Edupalli D., Raviprakash N., Navneetha T., Mahali S., Thoh M. (2011) Ras puts the brake on doxorubicin-mediated cell death in p53-expressing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7339–7347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8. Sen G. S., Mohanty S., Hossain D. M., Bhattacharyya S., Banerjee S., Chakraborty J., Saha S., Ray P., Bhattacharjee P., Mandal D., Bhattacharya A., Chattopadhyay S., Das T., Sa G. (2011) Curcumin enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by tailoring p65NFκB-p300 cross-talk in favor of p53-p300 in breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42232–42247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y., Xia F., Hermance N., Mabb A., Simonson S., Morrissey S., Gandhi P., Munson M., Miyamoto S., Kelliher M. A. (2011) A cytosolic ATM/NEMO/RIP1 complex recruits TAK1 to mediate the NF-κB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/MAPK-activated protein 2 responses to DNA damage. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 2774–2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jüliger S., Goenaga-Infante H., Lister T. A., Fitzgibbon J., Joel S. P. (2007) Chemosensitization of B-cell lymphomas by methylseleninic acid involves nuclear factor-κB inhibition and the rapid generation of other selenium species. Cancer Res. 67, 10984–10992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song L., Xiong H., Li J., Liao W., Wang L., Wu J., Li M. (2011) Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances resistance to apoptosis through activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 1839–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abe Y., Matsumoto S., Kito K., Ueda N. (2000) Cloning and expression of a novel MAPKK-like protein kinase, lymphokine-activated killer T-cell-originated protein kinase, specifically expressed in the testis and activated lymphoid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21525–21531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaudet S., Branton D., Lue R. A. (2000) Characterization of PDZ-binding kinase, a mitotic kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5167–5172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nandi A., Tidwell M., Karp J., Rapoport A. P. (2004) Protein expression of PDZ-binding kinase is up-regulated in hematologic malignancies and strongly down-regulated during terminal differentiation of HL-60 leukemic cells. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 32, 240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simons-Evelyn M., Bailey-Dell K., Toretsky J. A., Ross D. D., Fenton R., Kalvakolanu D., Rapoport A. P. (2001) PBK/TOPK is a novel mitotic kinase which is upregulated in Burkitt's lymphoma and other highly proliferative malignant cells. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 27, 825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao S., Dai J., Zhao W., Xia F., Zhou Z., Wang W., Gu S., Ying K., Xie Y., Mao Y. (2001) PDZ-binding kinase participates in spermatogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 33, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li S., Zhu F., Zykova T., Kim M. O., Cho Y. Y., Bode A. M., Peng C., Ma W., Carper A., Langfald A., Dong Z. (2011) T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) phosphorylation of MKP1 protein prevents solar ultraviolet light-induced inflammation through inhibition of the p38 protein signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29601–29609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zykova T. A., Zhu F., Vakorina T. I., Zhang J., Higgins L. A., Urusova D. V., Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2010) T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK) phosphorylation of Prx1 at Ser-32 prevents UVB-induced apoptosis in RPMI7951 melanoma cells through the regulation of Prx1 peroxidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29138–29146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oh S. M., Zhu F., Cho Y. Y., Lee K. W., Kang B. S., Kim H. G., Zykova T., Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2007) T-lymphokine-activated killer cell-originated protein kinase functions as a positive regulator of c-Jun-NH2-kinase 1 signaling and H-Ras-induced cell transformation. Cancer Res. 67, 5186–5194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu F., Zykova T. A., Kang B. S., Wang Z., Ebeling M. C., Abe Y., Ma W. Y., Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2007) Bidirectional signals transduced by TOPK-ERK interaction increase tumorigenesis of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 133, 219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abe Y., Takeuchi T., Kagawa-Miki L., Ueda N., Shigemoto K., Yasukawa M., Kito K. (2007) A mitotic kinase TOPK enhances Cdk1/cyclin B1-dependent phosphorylation of PRC1 and promotes cytokinesis. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 231–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu F., Gartenhaus R. B., Eichberg D., Liu Z., Fang H. B., Rapoport A. P. (2010) PBK/TOPK interacts with the DBD domain of tumor suppressor p53 and modulates expression of transcriptional targets including p21. Oncogene 29, 5464–5474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwon H. R., Lee K. W., Dong Z., Lee K. B., Oh S. M. (2010) Requirement of T-lymphokine-activated killer cell-originated protein kinase for TRAIL resistance of human HeLa cervical cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 830–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiménez-Lara A. M., Aranda A., Gronemeyer H. (2010) Retinoic acid protects human breast cancer cells against etoposide-induced apoptosis by NF-κB-dependent but cIAP2-independent mechanisms. Mol. Cancer 9, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bohuslav J., Chen L. F., Kwon H., Mu Y., Greene W. C. (2004) p53 induces NF-κB activation by an IκB kinase-independent mechanism involving phosphorylation of p65 by ribosomal S6 kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26115–26125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kinsella A. R., Smith D., Pickard M. (1997) Resistance to chemotherapeutic antimetabolites. A function of salvage pathway involvement and cellular response to DNA damage. Br. J. Cancer 75, 935–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bednarski B. K., Baldwin A. S., Jr., Kim H. J. (2009) Addressing reported pro-apoptotic functions of NF-κB. Targeted inhibition of canonical NF-κB enhances the apoptotic effects of doxorubicin. PLoS One 4, e6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tapia M. A., González-Navarrete I., Dalmases A., Bosch M., Rodriguez-Fanjul V., Rolfe M., Ross J. S., Mezquita J., Mezquita C., Bachs O., Gascón P., Rojo F., Perona R., Rovira A., Albanell J. (2007) Inhibition of the canonical IKK/NFκB pathway sensitizes human cancer cells to doxorubicin. Cell Cycle 6, 2284–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karin M. (1998) Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades as regulators of stress responses. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 851, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Panaretakis T., Laane E., Pokrovskaja K., Björklund A. C., Moustakas A., Zhivotovsky B., Heyman M., Shoshan M. C., Grandér D. (2005) Doxorubicin requires the sequential activation of caspase-2, protein kinase Cδ, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase to induce apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3821–3831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janssens S., Tschopp J. (2006) Signals from within. The DNA-damage-induced NF-κB response. Cell Death Differ. 13, 773–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gyrd-Hansen M., Meier P. (2010) IAPs. From caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rayet B., Gélinas C. (1999) Aberrant rel/nfkb genes and activity in human cancer. Oncogene 18, 6938–6947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Waes C. (2007) Nuclear factor-κB in development, prevention, and therapy of cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 1076–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Campbell K. J., Rocha S., Perkins N. D. (2004) Active repression of antiapoptotic gene expression by RelA(p65) NF-κB. Mol. Cell 13, 853–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li W., Melton D. W. (2012) Cisplatin regulates the MAPK kinase pathway to induce increased expression of DNA repair gene ERCC1 and increase melanoma chemoresistance. Oncogene 31, 2412–2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thoms H. C., Dunlop M. G., Stark L. A. (2007) p38-mediated inactivation of cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase 4 stimulates nucleolar translocation of RelA and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 67, 1660–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoda A., Toyoshima K., Watanabe Y., Onishi N., Hazaka Y., Tsukuda Y., Tsukada J., Kondo T., Tanaka Y., Minami Y. (2008) Arsenic trioxide augments Chk2/p53-mediated apoptosis by inhibiting oncogenic Wip1 phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18969–18979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee S. A., Jung M. (2007) The nucleoside analog sangivamycin induces apoptotic cell death in breast carcinoma MCF7/adriamycin-resistant cells via protein kinase Cδ and JNK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15271–15283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei M. C., Zong W. X., Cheng E. H., Lindsten T., Panoutsakopoulou V., Ross A. J., Roth K. A., MacGregor G. R., Thompson C. B., Korsmeyer S. J. (2001) Proapoptotic BAX and BAK. A requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 292, 727–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]