Abstract

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease that carries a significant disease burden in Australia and worldwide. The aim of this paper is to identify current barriers in the management of diabetes, ascertain whether there is a benefit from early detection and determine whether LDF has the potential to reduce the disease burden of DM by reviewing the literature relating to its current uses and development. In this literature review search terms included; laser Doppler flowmetry, diabetes mellitus, barriers to management, uses, future, applications, vasomotion, subcutaneous, cost. Databases used included Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct and Medline. Publications from the Australian government and textbooks were also utilised. Articles reviewed had access to the full text and were in English.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Laser Doppler Flowmetry, Vasomotion, Pre-diabetes.

What this study adds:

It addresses the barriers encountered in the management of DM and highlights the potential for the use of LDF the future management of DM.

Microvascular changes that occur in the setting of DM are explored.

Benefits and disadvantages of LDF in the context of DM are discussed.

Introduction

Current methods of diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) include identifying those at risk and screening with a fasting plasma glucose test or testing those with symptoms of hyperglycaemia. Despite current measures to aid the early detection of the disease, the prevalence is increasing and it is predicted to be the leading cause of disease burden for Australia in 2023.1 It is known that in DM, there is a loss of the random vasomotion in the microvasculature that exists in normal individuals which allows the adaptive adjustments in tissue perfusion. This derangement in vasomotion occurs before the clinical features of DM are apparent and can be detected with laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF).2 Diabetes Mellitus is a chronic metabolic condition encompassing a group of disorders characterised by hyperglycaemia.3 A deficiency of insulin alters the metabolism of carbohydrate, protein and fat, which results in the disturbance of electrolyte homeostasis, potentially lead to death from acute metabolic decompensation.4 Chronic metabolic derangement leads to organ damage especially the vascular system, resulting in the microvascular and macrovascular complications affecting the retina, nephrons, nerves and major organ systems. Currently 4% of the Australian population is diagnosed with DM with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) being the most common form, affecting up to 90% of all diabetics.1

Current barriers to management

Once the diagnosis of DM is made a lifelong commitment to management is required, which includes lifestyle modifications, follow-up with health professionals and monitoring of blood glucose levels. In addition to patient compliance, other barriers include side effects of medications such as symptomatic hypoglycaemia and weight gain with insulin and sulphonylureas.5

Despite the recent development of thorough management plans which aim to empower patients to take control of their diabetes, a randomised control trial evaluating their effectiveness shows that they are unsuccessful.7 Following the use of chronic disease self-management programs, there is limited evidence to show improvements in disease outcomes or reduction in the burden of health on health care resources, on the contrary these costs are increased.6 This is due to the complex multifaceted effects of the disease, which has varying effects on individuals requiring individualised plans taking into account geographical implications such as those in certain rural and remote areas and the psychosocial impact of the disease.7,8 Current difficulties in the management of DM suggest that there is potential for the consideration of any innovative methods that aid the early detection of the disease or its long-term management.

Pre-diabetes

Pre-diabetes is the development of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) leading to hyperglycaemia but not meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of DM. Pre-diabetes is asymptomatic and the diagnosis is made through screening based on the presence of risk factors. The current prevalence of pre-diabetes in Australia is 16.5%. The American Diabetes Prevention Program showed a 10% rate of progression from pre-diabetes to DM per year.9 Clinical trials showed that the treatment of pre-diabetes with lifestyle modifications and medications can prevent the progression to T2DM in 58% of individuals while delaying the onset in others. However there is a mixed consensus on the optimal cut off scores and risk factors that should be used for the detection of pre-diabetes.10, 11 Despite this benefit, prediction tools for T2DM are rarely implemented in clinical practice due to limitations in consultation times, clinician priorities12 and the generation of inaccurate scores in certain populations. For example, the AUSDRISK (Australian Diabetes Risk Assessment) tool overestimates the risk in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.11

Interestingly, a cluster-randomised controlled trial following over 15,000 individuals with type 2 diabetes for 10 years found that screening for diabetes showed no significant reduction in the outcome for cardiovascular, cancer or all- cause mortality.13 However, the absolute rate of death from cardiovascular and cancer was still higher in those not screened for diabetes than those who were. Measures used for screening were capillary blood glucose, HbA1c followed by an oral glucose tolerance test if appropriate. Individuals meeting the criteria for type 2 diabetes were then treated with a diabetes management plan. Although the study showed that the early detection of diabetes did not improve outcomes, it did not show the benefits of treating pre-diabetes and the impact of that on the progression of diabetes. Another limitation is that the study population was a UK based sample which did not mention high risk populations such as Asians, Polynesians and Aboriginals.

What is LDF?

In LDF, a beam of laser light is emitted from the probe head, which when applied to the skin will penetrate to a depth ranging from the epidermis to the subcutaneous tissue. Red blood cells (RBCs) traversing the region below the probe will be struck by laser light, partly reflecting it. As the RBCs move, a Doppler shift occurs. The illuminating light is detected by a photo-transducer which creates electrical signals that reflect the motion of the RBCs.14

Parameters extracted from LDF data

A range of parameters can be derived from LDF traces, these reflect the randomness of the vasomotion, the strength of impact of factors that affect the component frequencies of vasomotion,2 and strength of signal from the RBCs, which reflect the nonvectorial movement of RBC in blood vessels.15

Time series analysis is used to interpret LDF data, this involves analysing sequences of measurements to describe the system that produced the data16. Examples of such measurements include the amplitude, power and frequency of the oscillations in the subcutaneous blood vessels. This allows the characterisation of a system’s evolution through time which cannot be done with simple measurements such as the blood glucose level.

The relevance of LDF in DM

Autonomic dysfunction occurs early in the onset of DM as insulin deficiency or resistance leads to impaired vasomotion.17 Vasomotion is the spontaneous chaotic oscillation of vessel diameter in small arteries and arterioles, it is regulated by the automonic nervous system with influences from the cardiovascular, respiratory, myogenic, neurogenic and endothelial system at different frequencies.

Vasomotion is believed to be a mechanism which enables fine-tuning of perfusion by adjusting the volume and distribution of the local flow to the needs of the tissue in response to metabolic, pharmacologic and thermal stimuli.2, 18 Control of the process involves Ca2+, nitric oxide(NO), cGMP channels and the endothelial lining of blood vessels.19

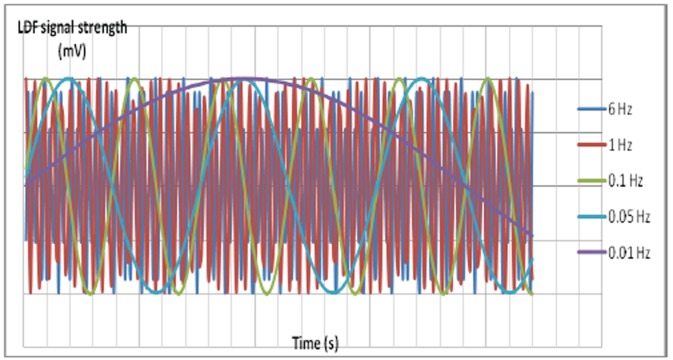

Figure 1. Simplified representation of the different frequencies that can be detected by LDF. 6Hz: cardiogenic component, 1Hz: respiratory component, 0.5 Hz: myogenic component, 0.1Hz: neurogenic component. 0.01 Hz: endothelial component. Specialised software can detect the component frequencies along with the corresponding amplitude, randomness of the oscillations, and other parameters.

α-adrenergic stimulation affects vasomotion by causing the activation of cGMP channels on the smooth muscle membrane leading to depolarisation, Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum leading to cellular contraction. Factors that affect this control system include modulators of the autonomic nervous system activity such as drugs, exercise and diet.20

A study of Rhesus monkeys in the normoglycaemic, pre- diabetic and diabetic groups showed that as DM progresses, the vasomotion measured from the dorsum of the foot becomes less random.2 The LDF results suggests that there is a progressive loss of the homeostatic capacity in the peripheral circulation to respond to environmental alterations. LDF data are more effective than traditional physiological measures such as FPG (fasting plasma glucose) and IRI (immunoreactive insulin) in distinguishing normoglycaemic from pre-diabetic states as the previously mentioned values are insensitive to time sequence and therefore provide no information about how the values evolve through time. Spectral analysis of LDF data provides information about the component frequencies of the signal and randomness of the microvascular flowmotion.16

A study on the vasomotion in the hind limb skeletal muscle of Wistar rats showed that insulin directly interacts with receptors on terminal arterial smooth muscle walls that control capillary recruitment.22 An insulin infusion corresponded to an increase in vasomotion detected as an A study on the vasomotion in the hind limb skeletal muscle of Wistar rats showed that insulin directly interacts with receptors on terminal arterial smooth muscle walls that control capillary recruitment.22 An insulin infusion corresponded to an increase in vasomotion detected as an increase in the 0.1 Hz frequency component of the LDF signal which attributes to an increased amplitude of rhythmic contractions of vascular smooth muscle. In contrast, when an insulin resistant state was induced by the infusion of a peripheral vasoconstrictor, the opposite occurred. LDF studies of the cutaneous circulation in the anterior forearm in type 1 diabetics also show a derangement in the 0.1Hz component of the LDF signal. In humans this frequency reflects the sympathetic component of vasomotion.23 Sympathetic impairment of the microcirculatory vasomotion control appears to be a potential early indicator of autonomic dysfunction in diabetes.21, 23, 24

A review of the epidermal vasomotion in diabetic and patients with metabolic syndrome support the dysfunction of vasomotion present in the insulin resistant state.25 Furthermore, the review shows that abnormalities of cutaneous microcirculatory vasomotion is related to a loss of the neurogenic vasodilative mechanism mediated by long distance reflexes and local factors, such as the response of the small fibre nociceptive neurons. This mechanism is more prominent in hairy skin compared to hairless skin and is also present in skeletal muscle as well as other internal organs.

Microalbuminuria is associated with effects on vasomotion influenced by endothelial factors. A suggestion is that NO impairment and endothelial dysfunction of the glomerular endothelium is similarly reflected in the cutaneous microcirculation.26

Current uses of LDF

In research, LDF has been used to analyse the perfusion of organs including:

cochlear blood flow in response to dilating agents;27

renal medullary blood flow in reperfusion injury;28

hepatic blood flow and in response to injury;29

gastrointestinal blood flow in surgery;30

peripheral nerve function;31

assess blood flow to the dental pulp;32

skin blood flow studies to analyse its physiology and the effect of pharmacological agents.33

Clinically LDF has been used to:

Use of LDF in the future

Benefits

LDF is a non-invasive method of investigation that is sensitive to detecting changes in vasomotion and can reveal the relative real time perfusion status of the microvasculature. Reproducible results from individuals can be achieved in a controlled environment.36, 37

LDF can be utilised in the long-term monitoring of DM. Measurements of vasomotion reflects the activity of modifiable factors in DM management such as caffeine, smoking, exercise and drugs affecting blood pressure.21 Improvements revealed by quantitative LDF results may have a better impact on motivating individuals to maintain lifestyle modifications.

Disadvantages

Variability exists in results from different tissue types and interference to the recording occurs from body movements.36 LDF has a lack of specificity for detecting DM and as mentioned above, derangements in vasomotion are not exclusive to DM.

Additional limitations include the high cost and size of the equipment. This limits its portability in clinical practice and reduces its cost effectiveness. The current cost of the LDF monitor is approximately $13,000 AUD.37 However, recent developments are in place to produce smaller portable LDF monitors that cost less without a compromise in quality.38

Analysis of LDF traces require a recording of appropriate duration in order for a time-frequency analysis to be made with logarithmic regression. An experienced operator is required to extract the LDF traces appropriate for analysis with the use of specialised software.36

Conclusion

Further research is required to justify the use of LDF in the early detection of DM. This includes standardising a method of measurement in the human population to ensure a LDF trace of adequate quality, cost-effectiveness of use, portability of the equipment, development of guidelines on the cut off points and parameters used to determine a significant change in vasomotion. LDF is likely to be a component of a DM risk scoring tool to evaluate individuals as there are multifactorial risk factors for DM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Menzies Research Institute Tasmania & School of Medicine, University of Tasmania.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program supported by Menzies Research Institute Tasmania & School of Medicine, University of Tasmania.

Please cite this paper as: Au M, Rattigan S. Barriers to the management of Diabetes Mellitus – is there a future role for Laser Doppler Flowmetry? AMJ 2012, 5, 12, 627-632.http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2012.1526

References

- 1.Penn D. Diabetes, Australian facts 2002. . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tigno XT, Hansen BC, Nawang S, Shamekh R, Albano AM. Vasomotion becomes less random as diabetes progresses in monkeys. Microcirculation. 2011;18(6):429–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, 17th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill;; 2008. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston S. 21st edn. London:Churchill Livingstone: 2010. Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes Australia, Practitioners RACoG. Diabetes management in general practice: Diabetes Australia; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenhalgh T. Patient and public involvement in chronic illness: beyond the expert patient. BMJ. 2009;338:b49. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khunti K, Gray LJ, Skinner T, Carey ME, Realf K, Dallosso H. et al. Effectiveness of a diabetes education and self management programme (DESMOND) for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: three year follow-up of a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ. 2012;344:e2333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner T, Ellis I. Tale of two courthouses: A critique of the underlying assumptions in chronic disease Self- management for Aboriginal people. Australas Med J. 2009;1(14):239–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twigg SM, Kamp MC, Davis TM, Neylon EK, Flack JR. Prediabetes: a position statement from the Australian Diabetes Society and Australian Diabetes Educators Association. Med J Aust. 2007 May 7;186(9):461–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang P, Engelgau MM, Valdez R, Cadwell B, Benjamin SM, Narayan KMV. Efficient cutoff points for three screening tests for detecting undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1321–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHMRC A. National Evidence Based Guideline for the Primary Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble D, Mathur R, Dent T, Meads C, Greenhalgh T. Risk models and scores for type 2 diabetes: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;343:d7163.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons RK, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Sharp SJ, Sargeant LA, Williams KM, Prevost AT. et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes and population mortality over 10 years (ADDITION-Cambridge): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 Nov;17380(9855):1741–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61422-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swiontkowski MF. Laser Doppler Flowmetry— Development and Clinical Application. The Iowa Orthop J. 1991;11:119. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark MG, Clark ADH, Rattigan S. Failure of laser Doppler signal to correlate with total flow in muscle: Is this a question of vessel architecture? . Microvas Res. 2000;60(3):294–301. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2000.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albano AM, Brodfuehrer PD, Cellucci CJ, Tigno XT, Rapp PE. Time series analysis, or the quest for quantitative measures of time dependent behavior. Philippine Science Letters. 2008;1(1):18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stergiopulos N, Porret CA, De Brouwer S, Meister JJ. Arterial vasomotion: effect of flow and evidence of nonlinear dynamics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274(6):H1858–H64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holowatz LA, Thompson-Torgerson CS, Kenney WL. The human cutaneous circulation as a model of generalized microvascular function. J Applied Physiol. 2008;105(1):370–2. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00858.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi M. Diagnostic value of skin vasomotion investigation in vascular diseases. Annios P, Rossi M, Pham TD, Falugi C, Bussing A, Koukkou M, editors. Advances in Biomedical Research. Cambridge: World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society. 2010:374–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobsen JCB, Aalkjær C, Nilsson H, Matchkov VV, Freiberg J, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Activation of a cGMP-sensitive calcium-dependent chloride channel may cause transition from calcium waves to whole cell oscillations in smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(1):H215–H28. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00726.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer M, Rose C, Hülsmann JO, Schatz H, Pfohl M, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Impaired 0.1-Hz vasomotion assessed by laser Doppler anemometry as an early index of peripheral sympathetic neuropathy in diabetes. Microvas Res. 2003;65(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(02)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman JMB, Dwyer RM, St-Pierre P, Richards SM, Clark MG, Rattigan S. Decreased microvascular vasomotion and myogenic response in rat skeletal muscle in association with acute insulin resistance. J Physiol. 2009;587(11):2579–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernardi L, Rossi M, Leuzzi S, Mevio E, Fornasari G, Calciati A. et al. Reduction of 0.1 Hz microcirculatory fluctuations as evidence of sympathetic dysfunction in insulin-dependent diabetes. Cardiovas Res. 1997;34(1):185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aso Y, Inukai T, Takemura Y. Evaluation of Skin Vasomotor Reflexes in Response to Deep Inspiration in Diabetic Patients by Laser Doppler Flowmetry: A new approach to the diagnosis of diabetic peripheral autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(8):1324–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.8.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinik AI, Erbas T, Park TS, Stansberry KB, Scanelli JA, Pittenger GL. Dermal neurovascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1468–75. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmiedel O, Schroeter ML, Harvey JN. Microalbuminuria in Type 2 diabetes indicates impaired microvascular vasomotion and perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(6):H3424–H31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00558.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller JM, Ren TY, Nuttall AL. Studies of inner ear blood flow in animals and human beings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112(1):101. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570308-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regner KR, Roman RJ. Role of medullary blood flow in the pathogenesis of renal ischemia–reperfusion injury . Curr Opin in Nephrol and Hypertens . 2012;21(1):33. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834d085a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollmar B, Menger MD. The Hepatic Microcirculation: Mechanistic Contributors and Therapeutic Targets in Liver Injury and Repair. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(4):1269–1339. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiltebrand LB, Koepfli E, Kimberger O, Sigurdsson GH, Brandt S. Hypotension during fluid-restricted abdominal surgery: effects of norepinephrine treatment on regional and microcirculatory blood flow in the intestinal tract. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(3):557. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820bfc81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu QG, Midha R, Zochodne DW. The microvascular impact of focal nerve trunk injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(3):639–46. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy E, Alliot-Licht B, Dajean-Trutaud S, Fraysse C, Jean A, Armengol V. Evaluation of the ability of laser Doppler flowmetry for the assessment of pulp vitality in general dental practice. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(4):615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton DJ, Burke D, Khan F, McLeod GA, Belch JJF, McKenzie M. et al. Skin blood flow changes in response to intradermal injection of bupivacaine and levobupivacaine, assessed by laser Doppler imaging. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25(6):626. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2000.9853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludovico J, Bernardes R, Pires I, Figueira J, Lobo C, Cunha-Vaz J. et al. Alterations of retinal capillary blood flow in preclinical retinopathy in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Graefe's Arch Clinical Ophthal. 2003;241(3):181–6. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swiontkowski MF. Criteria for bone debridement in massive lower limb trauma. Clin Ortho and Relat Res. 1989;243:41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajan V, Varghese B, Van Leeuwen TG, Steenbergen W. Review of methodological developments in laser Doppler flowmetry. Lasers Medical Sci. 2009;24(2):269–83. doi: 10.1007/s10103-007-0524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klonizakis M, Manning G, Donnelly R. Assessment of lower limb microcirculation: exploring the reproducibility and clinical application of laser Doppler techniques. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2011;24(3):136–43. doi: 10.1159/000322853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh CH, Yeong EK, Lin KP. Portable Laser Doppler Flowmetry in Studying the Effect of Diabetes Mellitus on Cutaneous Microcirculation. J Med Biol Eng. 2003;23(1):13–8. [Google Scholar]