Abstract

Background/objectives:

Hypertension affects about 30% of adults worldwide. Garlic has blood pressure-lowering properties and the mechanism of action is biologically plausible. Our trial assessed the effect, dose–response, tolerability and acceptability of different doses of aged garlic extract as an adjunct treatment to existing antihypertensive medication in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Subjects/methods:

A total of 79 general practice patients with uncontrolled systolic hypertension participated in a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled dose–response trial of 12 weeks. Participants were allocated to one of three garlic groups with either of one, two or four capsules daily of aged garlic extract (240/480/960 mg containing 0.6/1.2/2.4 mg of S-allylcysteine) or placebo. Blood pressure was assessed at 4, 8 and 12 weeks and compared with baseline using a mixed-model approach. Tolerability was monitored throughout the trial and acceptability was assessed at 12 weeks by questionnaire.

Results:

Mean systolic blood pressure was significantly reduced by 11.8±5.4 mm Hg in the garlic-2-capsule group over 12 weeks compared with placebo (P=0.006), and reached borderline significant reduction in the garlic-4-capsule group at 8 weeks (−7.4±4.1 mm Hg, P=0.07). Changes in systolic blood pressure in the garlic-1-capsule group and diastolic blood pressure were not significantly different to placebo. Tolerability, compliance and acceptability were high in all garlic groups (93%) and highest in the groups taking one or two capsules daily.

Conclusions:

Our trial suggests aged garlic extract to be an effective and tolerable treatment in uncontrolled hypertension, and may be considered as a safe adjunct treatment to conventional antihypertensive therapy.

Keywords: hypertension, garlic, nutritional medicine

Introduction

Hypertension affects one billion or one in four adults worldwide, and attributes to about 40% of cardiovascular-related deaths.1, 2 Current medical treatment with standard antihypertensive medication is not always effective, leading to a large proportion of uncontrolled hypertension. In Australia, 24% or 3 million of the adult population remained uncontrolled hypertensive in 2003.3 In addition, side effects and complexity of treatment influence treatment adherence.4, 5 As interest in and use of complementary and alternative medicines is high in patients with cardiovascular disease,6, 7 there is a need to explore the integration of complementary and alternative medicine into the treatment of hypertension.

Garlic supplements have been associated with a blood pressure (BP)-lowering effect of clinical significance in hypertensive patients.8, 9, 10 Although there are several garlic preparations on the market, including garlic powder, garlic oil and raw or cooked garlic, aged garlic extract is the preparation of choice for BP treatment. Aged garlic extract contains the active and stable component S-allylcysteine, which allows standardisation of dosage.11 In addition, aged garlic extract has a higher safety profile than other garlic preparations, and does not cause bleeding problems if taken with other blood-thinning medicines such as warfarin.12, 13, 14

The antihypertensive properties of garlic have been linked to stimulation of intracellular nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide production, and blockage of angiotensin II production, which in turn promote vasodilation and thus reduction in BP.15, 16, 17, 18

Here we assess the effect, dose–response, tolerability and acceptability of different doses of aged garlic extract as an adjunct treatment to existing antihypertensive medication in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Subjects and methods

Subjects and study design

Adult patients with uncontrolled hypertension (systolic BP (SBP) ⩾140 mm Hg as recorded on their medical records in the past 6 months) from two general practices in metropolitan Adelaide, South Australia, were invited to participate in this double-blind randomised placebo-controlled parallel 12-week trial. We included primarily patients who were on an established plan of prescription antihypertensive medication for at least 2 months, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics or β-blockers, and whose general practitioner was not planning to change the medication plan during the trial. We excluded patients with unstable or serious illness, for example, dementia, terminal illness, recent bereavement, secondary hypertension, recent significant medical diagnosis or pregnancy. Patients who were not able to provide informed consent, or were taking daily garlic supplements, were also excluded. We identified patients by search of electronic medical records using the practice clinical software package and the PEN Computer Systems Clinical Audit Tool,19 and assessed eligibility in liaison with the patients' treating general practitioners. Patients who were interested in participating in the trial provided written consent by response to the invitation letter. Patients' eligibility was assessed at their first visit with the research nurse at their usual practice. Only patients whose SBP was ⩾135 mm Hg under trial conditions were enroled in the trial. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and The University of Adelaide. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, number ACTRN12611000581965.

Allocation and treatment

Consenting eligible patients were randomly allocated to one of three garlic groups (g1, g2 and g4) or placebo using a computer-generated random number table provided by an independent consulting statistician. Patients were assigned either one, two or four capsules daily of Kyolic aged garlic extract (High Potency Everyday Formula 112; Wakunaga/Wagner, Sydney, Australia)20 containing either 240/480/960 mg of aged garlic extract and 0.6/1.2/2.4 mg S-allylcysteine or placebo capsules for 12 weeks. Placebo capsules were matched in number, shape, size, colour and odour to the active capsules and were packaged in identical opaque containers by independent staff not involved in the trial. Sachets with a drop of liquid Kyolic were added to the containers for garlic odour. Patients, investigators and the research nurse were blinded to treatment allocation. Blinding success of patients was assessed at the end of the trial by questionnaire. Patients were instructed to take all trial capsules with the evening meal. Patients were reminded to take their usual prescription medication as instructed by their doctor. Compliance was assessed by daily entries in provided calendars.

BP monitoring

Primary outcome measures were SBP and diastolic BP (DBP) at 4, 8 and 12 weeks compared with baseline. BP was taken by a trained research nurse using a single calibrated and validated digital sphygmomanometer with appropriate sized cuffs (Omron HEM-907; JA Davey Pty Ltd, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). The display of the sphygmomanometer was positioned away from the patient to assure blinding to the BP readings. BP measurements were taken with the patient in a seated position with their arm supported at heart level, after 5 min rest, after abstinence from food, nutritional supplements, caffeinated beverages and smoking for a minimum of 2 h before the appointment at approximately the same time/day of the week. BP was recorded as three serial measurements at intervals of 30 s. The mean of the three BP measurements was used in the analysis. At the patients' baseline assessment, BP was measured on both arms, and the arm with the higher mean reading was used in subsequent visits. If the three SBP readings had more than 8 mm Hg difference, a second BP series was recorded.

Tolerability and acceptability

Tolerability of trial medication was monitored throughout the trial by questionnaire at the 4-weekly appointments. Acceptability and willingness to continue the trial treatment was assessed at 12 weeks using a questionnaire tested in previous trials.10, 21 Patients who dropped out from the trial were followed up by phone to assess acceptability and their reasons for withdrawal.

Sample size

A sample size of 84 patients, 21 in each of the four groups, was calculated based on the following assumptions: (a) to detect a difference of 10 mm Hg SBP (s.d.=10) in BP change between each of the active treatment (g1, g2 and g4: n=21, 21 and 21) and placebo groups (ptotal=p1+p2+p4 capsules: n=7+7+7=21), with 80% power and 95% confidence;10 (b) to account for 10% drop-out or non-attendance at one or more appointments; (c) to adjust for clustering using a design effect of 1.2 based on the formula: Design effect=(1+(size of cluster−1) × intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.02). Assuming a response rate of 15%, we estimated that we would need to invite about 840 hypertensive patients from the two large general practices.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using PASW version 18 and SAS version 9.3. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Differences between the groups in baseline characteristics were assessed by χ2 and Fisher's exact test of binominal variables (gender, smoking, family history of premature cardiovascular disease, type of BP medication), by Kruskal–Wallis test for ordinal variables (number of BP medication) or one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni adjustment and post hoc Dunnett's test for continuous variables (age, body mass index (BMI), blood lipids) after testing for their normal distribution by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

A linear mixed-effects model analysis was used to assess the mean differences of SBP and DBP between the groups at 4, 8 and 12 weeks and over time compared with baseline. Compound symmetry was assumed. For covariate analysis, we incorporated the following variables into the model to test for potential confounding: age, BMI, gender, smoking status and number of BP medicines. Analysis by type of BP medication was not meaningful because of small patient numbers in the subgroups.

Primary analyses were by intention to treat, including all available data regardless of protocol deviations, and planned adjusted analysis, excluding data points owing to BP medication change or participant's non-compliance.

Tolerability was analysed descriptively and differences between the groups assessed by χ2 test. Differences in acceptability of the treatment between the groups were assessed by Kruskal–Wallis test. Blinding success was assessed by Fisher's exact test for garlic versus placebo, and Kruskal–Wallis test to ascertain differences between the garlic groups.

Results

Participants

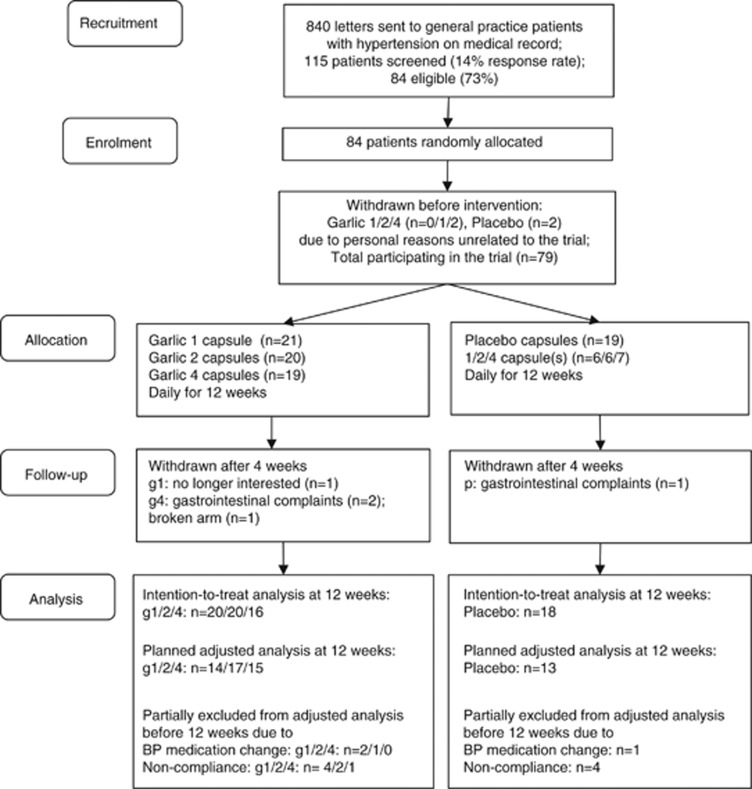

The trial was conducted in Adelaide, South Australia, between August 2011 and March 2012. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension on medical record were recruited from two metropolitan general practices. Of the 840 patients invited, 14% responded and were screened for eligibility, and 84 patients were enroled randomly allocated to one of four treatment groups. Five patients withdrew before further assessment because of personal reasons unrelated to the trial (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the 79 patients participating in the trial were not significantly different between the garlic and placebo groups (Table 1). A total of 42 men and 37 women with a mean age of 70±12 years participated in the trial. Participants took on average 2±1 different types of antihypertensive medication (range 0–4), with angiotensin II receptor blockers the most often prescribed (46%). Family history of cardiovascular disease was reported by almost half of the participants, including premature cardiovascular events by 15% (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Trial flow chart. g1, garlic-1-capsule group; g2, garlic-2-capsule group; g4, garlic-4-capsule group; p, placebo group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | All participantsa (n=79) | Garlic 1 (n=21) | Garlic 2 (n=20) | Garlic 4 (n=19) | Placebo (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (m/f) | 42/37 | 12/9 | 12/8 | 9/10 | 9/10 |

| |

Mean±s.d. (range) |

Mean±s.d. |

|||

| Age (years) | 69.8±11.9 (42–101) | 70.1±12.4 | 67.5±11.8 | 70.4±13.1 | 71.5±10.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3±4.9 (16.5–40.2) | 29.7±5.8 | 28.8±5.3 | 28.8±4.0 | 29.9±4.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.1±1.2 (3.0–8.5) | 5.0±1.0 | 4.6±0.9 | 5.4±1.2 | 5.5±1.3 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.9±1.0 (0.9–6.0) | 2.6±0.7 | 2.6±0.8 | 3.2±1.3 | 3.3±1.2 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.4±0.3 (0.9–2.3) | 1.4±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | 1.4±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.7±1.0 (0.5–6.1) | 1.9±1.1 | 1.7±1.4 | 1.7±0.7 | 1.6±0.8 |

| Mean number of BP drugs | 1.7±0.9 (0–4) | 1.9±1.1 | 1.6±0.7 | 1.5±0.9 | 1.8±0.9 |

| |

N (%) |

||||

| Current smoker | 9 (9) | 1 (5) | 5 (33) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Family history of CVD | 38 (48) | 14 (67) | 13 (65) | 11 (58) | 10 (53) |

| Myocardial infarction | 18 (23) | 5 (24) | 4 (20) | 4 (21) | 5 (26) |

| Stroke | 13 (17) | 5 (24) | 3 (15) | 3 (16) | 2 (11) |

| Hypertension | 10 (13) | 4 (19) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 3 (16) |

| CAD, pacemaker, bypass | 7 (9) | 4 (20) | 3 (16) | ||

| Premature CVDb (m<55 years, f<65 years) | 12 (15); 25% of all CVD | 4 (19) | 4 (20) | 4 (21) | |

| Type of BP drug | |||||

| A2RB | 36 (46) | 8 (38) | 9 (45) | 8 (42) | 11 (58) |

| D | 31 (39) | 10 (48) | 6 (30) | 4 (21) | 11 (58) |

| CCB | 30 (38) | 8 (38) | 9 (45) | 9 (47) | 4 (21) |

| ACEI | 27 (34) | 10 (48) | 6 (30) | 6 (32) | 5 (26) |

| BB | 12 (15) | 4 (19) | 1 (5) | 3 (16) | 4 (21) |

| Number of BP drug types | |||||

| 0 | 3 (4) | 1 (5) | 2 (11) | 8 (42) | |

| 1 | 32 (41) | 7 (33) | 11 (55) | 7 (37) | 8 (42) |

| 2 | 31 (39) | 8 (38) | 7 (35) | 7 (37) | 2 (11) |

| 3 | 10 (13) | 3 (14) | 2 (10) | 3 (16) | 1 (5) |

| 4 | 3 (4) | 2 (10) | |||

Abbreviations: A2RB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, β-blockers; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; BP, blood pressure; CCB, calcium channel blockers; CVD, cardiovascular disease; D, diuretics; f, female; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; m, male; s.d., standard deviation.

No significant differences in baseline values between garlic and placebo groups.

Includes myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery disease, but does not include hypertension only.

Compliance and withdrawals

Despite doctors being aware of a patient's participation in this trial, BP medication regimen was changed for four participants during the trial (g1: n=2 and g2: n=1 before 4 weeks; P=1 before 12 weeks). As change in BP medication was expected to have influenced patient's BP and biased the effect of the trial supplement, the correlating data points were excluded from planned adjusted analysis.

Patient's compliance was assessed by calendar entries. We excluded data points from planned adjusted analysis if compliance was <80%, which was more pronounced around the Christmas/New Year's holiday period.

Five patients withdrew after 4 weeks, three due to gastrointestinal complaints (g4: n=2; P=1), one due to a broken arm (g4: n=1) and one was no longer interested in participating (g1: n=1).

Blood pressure

Intention-to-treat analysis of 79 patients revealed a significant reduction in SBP from baseline in the garlic-2 group compared with placebo over 12 weeks (mean diff. SBP±s.e. (95% confidence interval)=−9.7±4.8 (−19.3; −0.1) mm Hg; P=0.03; Table 2). Intention-to-treat analysis of DBP did not reveal a significant effect of treatment between the groups.

Table 2. Dose–response effect of garlic on blood pressure.

| Analysis | Weeks | Garlic 1 | Garlic 2 | Garlic 4 | Placebo | Mean difference (95%CI) between groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

n |

Mean (s.e.) |

n |

Mean (s.e.) |

n |

Mean (s.e.) |

n |

Mean (s.e.) |

Garlic 1 vs placebo |

Garlic 2 vs placebo |

Garlic 4 vs placebo |

| SBP | ||||||||||||

| ITTa | 0 | 21 | 150.8 (2.8) | 20 | 149.3 (2.9) | 19 | 149.4 (3.0) | 19 | 148.6 (3.0) | 2.2 (−6;10.4) | 0.7 (−7.7; 9.1) | 0.8 (−7.6;9.2) |

| (n=79) | 4 | 20 | 137.8 (2.9) | 20 | 145.8 (2.9) | 18 | 138.3 (3.0) | 19 | 141.0 (3.0) | −3.2 (−11.4;5) | 4.8 (−3.6;13.2) | −2.7 (−11.1;5.7) |

| 8 | 20 | 137.3 (2.9) | 20 | 131.4 (2.9) | 16 | 133.8 (3.2) | 18 | 139.1 (3.0) | −1.8 (−10.2;6.6) | −7.7 (−16.1;0.7) | −5.3 (−14.1;3.5) | |

| 12 | 17 | 142.8 (3.0) | 18 | 126.9 (3.0) | 16 | 134.1 (3.2) | 17 | 135.9 (3.1) | 6.8 (−1.8;15.4) | −9.1 (−17.7;−0.5)* | −1.9 (−10.9;7.1) | |

| Changec 0–12 | −8.1 (4.0) | −22.4 (4.0) | −15.4 (4.2) | −12.7 (4.2) | 4.6 (−7;16.2) | −9.7 (−19.3;−0.1)* | −2.7 (−14.7;9.3) | |||||

| Planned adjustedb | 0 | 18 | 148.7 (2.8) | 20 | 149.3 (2.6) | 19 | 149.4 (2.7) | 17 | 148.8 (2.8) | −0.2 (−8.2;7.8) | 0.5 (−7.3;8.3) | 0.6 (−7.2;8.4) |

| (n=74) | 4 | 17 | 137.7 (2.8) | 19 | 144.5 (2.7) | 18 | 138.3 (2.7) | 16 | 142.8 (2.9) | −5.1 (−13.1;2.9) | 1.7 (−6.1;9.5) | −4.5 (−12.5;3.5) |

| 8 | 17 | 135.2 (2.8) | 20 | 131.4 (2.6) | 15 | 132.6 (2.9) | 16 | 140.0 (2.9) | −4.8 (−16.4;−0.8) | −8.6 (−16.4;−0.8)* | −7.4 (−15.6;0.8)(*) | |

| 12 | 14 | 138.8 (3.1) | 17 | 126.8 (2.8) | 15 | 132.4 (3.0) | 14 | 138.1 (3.1) | 0.7 (−19.8;−3) | −11.4 (−19.8;−3)** | −5.7 (−14.3;2.9) | |

| Changec 0–12 | −9.8 (4.0) | −22.5 (3.7) | −17.1 (3.9) | −10.7 (4.0) | 0.9 (−22.6;−1) | −11.8 (−22.6;−1)** | −6.4 (−17.4;4.6) | |||||

| DBP | ||||||||||||

| ITTa | 0 | 21 | 77.1 (2.7) | 20 | 75.6 (2.8) | 19 | 75.9 (2.8) | 19 | 76.0 (2.8) | 1.1 (−6.7;8.9) | −0.4 (−8;7.2) | −0.1 (−7.7;7.5) |

| (n=79) | 12 | 19 | 72.1 (2.8) | 16 | 67.1 (2.8) | 16 | 70.1 (3.0) | 17 | 70.2 (2.9) | 2.0 (−6;10) | −3.0 (−11;5) | −0.1 (−8.3;8.1) |

| Changec 0–12 | −5.0 (4.0) | −8.5 (4.0) | −5.9 (4.0) | −5.8 (4.0) | NE | NE | NE | |||||

| Planned adjustedb | 0 | 18 | 76.9 (2.9) | 20 | 75.6 (2.8) | 19 | 75.9 (2.8) | 17 | 76.6 (3.0) | |||

| (n=74) | 12 | 14 | 70.0 (3.1) | 17 | 66.6 (2.8) | 15 | 69.5 (3.0) | 14 | 71.9 (3.1) | −1.9 (−10.5;6.7) | −5.3 (−13.7;3.1) | −2.4 (−10.8;6) |

| Change3 0–12 | −6.9 (1.9) | −9.0 (1.8) | −6.4 (1.9) | −4.7 (1.9) | NE | NE | NE | |||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimated; s.e., standard error; all values in mm Hg.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; (*)P<0.1.

ITT, intention-to-treat analysis includes all data points available regardless of protocol deviations, including change of prescription blood pressure medication, or non-compliance.

Planned adjusted analysis excluded data points after prescription blood pressure medication was changed during the trial, or because of participant's non-compliance.

Mean difference (s.e.) in blood pressure within group over time (0–12 weeks); 95% CI=mean±2 s.e.

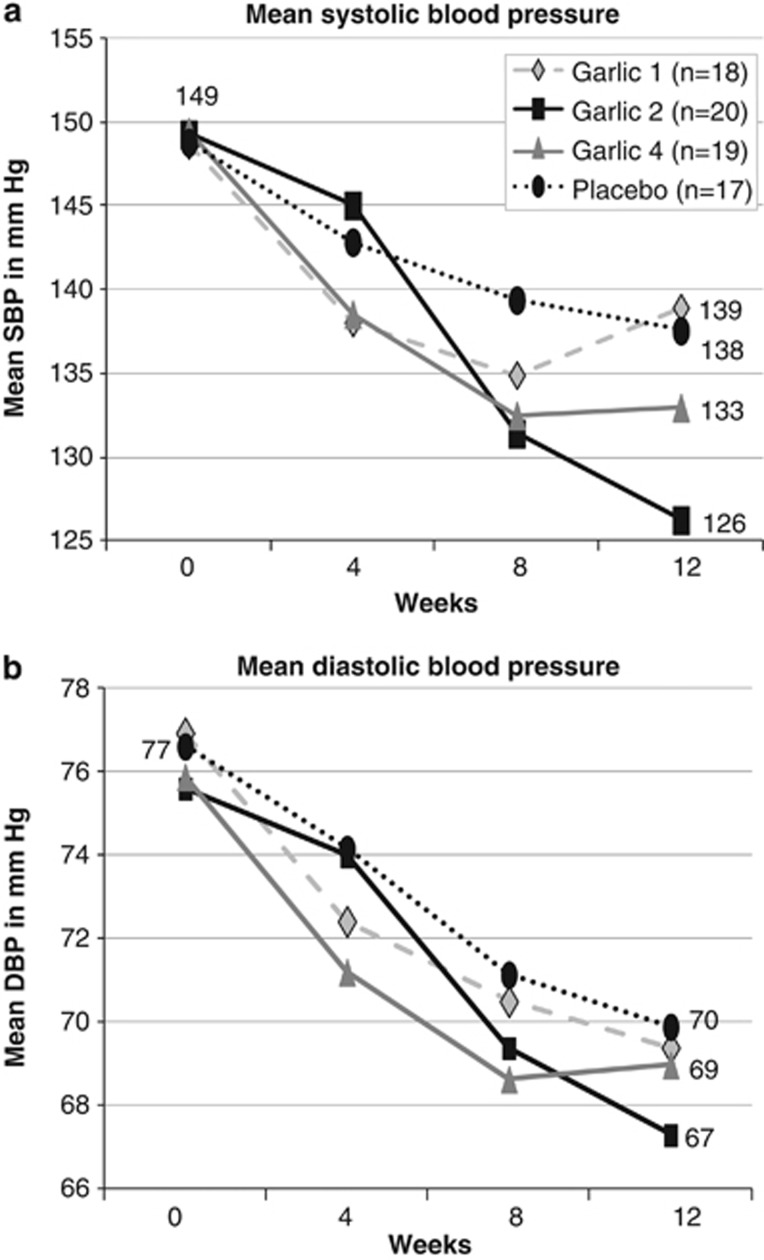

In the planned adjusted analysis, we excluded patients whose prescription BP medication was changed by their doctor between baseline and visit 1 at 4 weeks measurements (n=4) and those with poor compliance (n=2), as these deviations from protocol would have influenced BP readings. Figure 2 illustrates the results of planned adjusted analysis of 74 patients, which revealed a significant difference in reduction of SBP between the garlic-2 group and placebo at 8 and 12 weeks, and over time compared with baseline (g2; 0–12 weeks: mean diff. SBP±s.e. (95% confidence interval)=−11.8±5.4 (−22.6;−1.0) mm Hg; P=0.006; Table 2). SBP reduction in the garlic-4 group reached borderline significance at 8 weeks compared with placebo. Although SBP dropped significantly within the garlic-1 group at 12 weeks, the change did not reach statistical significance when compared with placebo.

Figure 2.

Effect of aged garlic extract on blood pressure. Mean SBP (a) and DBP (b) over 12 weeks of all participants in the planned adjusted analysis.

Treatment did not have a noticeable effect in all patients. Change of SBP ranged from −40 to +5 mm Hg across all groups. SBP did not change by more than 5 mm Hg in a third of the participants (33.8%) over the course of the trial independent of group allocation (SBP change <5 mm Hg: g1=43% g2=25% g4=26%, p=32%). Covariate analysis by gender, age, BMI, smoking status and number of BP medication did not explain differences in patients' response to treatment. Analysis by type of BP medication was limited by the small sample sizes in subgroups and complicated by the number of drug combinations, and did not reveal any influence of BP medication type on the treatment effect.

Planned adjusted analysis of DBP revealed the largest reduction in DBP in the garlic-2 group (mean diff. DBP±s.e. (95% confidence interval): −5.3±4.2 (−13.7; 3.1) mm Hg), albeit insignificantly different to placebo (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Tolerability, acceptability and blinding

Three participants (4%) withdrew because of gastrointestinal side effects after 4 weeks, two in the garlic-4 group and one in the placebo group (P>0.05). Participants in the garlic groups reported minor complaints in the first week of the trial, including constipation, bloating, flatulence, reflux, garlic taste and difficulty swallowing the capsules (23%), and dry mouth and cough in the garlic-1 (n=2) and placebo group (n=1) (Table 3). A larger number of participants reported side effects in the garlic-4 group compared with the garlic-2 and garlic-1 groups, albeit not statistically significant. Participants found ways to overcome the reported minor complaints, for example, by taking the capsules in the morning rather than in the evening.

Table 3. Tolerability and acceptability.

|

Groupc |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garlic 1 | Garlic 2 | Garlic 4 | Placebo | ||

| Total number | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=19 | |

| (A) Tolerability | |||||

| Side effects | N (%) | ||||

| Gastrointestinal discomfort | 2 (11) | 1 (5) | |||

| Constipationa | 1 (5) | ||||

| Bloating, flatulencea | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | |||

| Refluxa | 1 (5) | 4 (21) | |||

| Garlic tastea | 2 (10) | ||||

| Dry mouth, cougha | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |||

| Difficulty swallowing because of number and size of capsules | 2 (11) | ||||

| Total side effects | 3 (14) | 3 (15) | 8 (42) | 2 (11) | |

| (B) Acceptabilityb | |||||

| Ease of taking capsules | ++/+ | 13/6 (91) | 12/6 (90) | 8/5 (68) | 9/7 (84) |

| −−/− | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (5) | 0/1 (5) | |

| Acceptability | ++/+ | 12/8 (95) | 11/9 (100) | 6/1 (84) | 6/11 (90) |

| −−/− | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1/0 (5) | 0/1 (5) | |

| Willingness to continue after trial | ++/+ | 11/8 (91) | 5/11 (80) | 5/8 (68) | 7/7 (74) |

| −−/− | 0 (0) | 1/0 (5) | 2/0 (11) | 0/1 (5) | |

| Willingness to pay for supplementd | ++/+ | 9/4 (62) | 1/13 (70) | 3/9 (63) | 6/5 (58) |

| −−/− | 0 (0) | 1/1 (10) | 3/0 (16) | 1/1 (11) | |

Participants reported minimal side effects in the first week of the trial, but did not find these side effects bothersome and found ways to overcome these.

Responses to questions of acceptability were assessed on a five-point Likert scales ranging from 1=very easy/very acceptable/strongly agree (++) to 5=very hard/very unacceptable/strongly disagree (−−).

Reported side effects and acceptability of treatment were not statistically significant between the garlic and placebo groups.

The willingness to pay for supplements was stronger in the garlic-1-capsule group compared with garlic-2 and -4 capsule groups (P<0.05).

Most of the participants found taking the trial capsules easy (gall: 83% p: 84%) and acceptable (gall: 93% p: 90% Table 3). There was a trend towards greater ease and acceptability with the allocation of fewer capsules daily (garlic-1 and -2 versus garlic-4), albeit this difference was not statistically significant. Most of the participants (gall: 80% p: 74%) reported that they would be willing to continue taking the capsules after the trial was finished, if the treatment was effective in reducing their BP. About two-thirds of participants (gall: 65% p: 58%) were willing to pay the estimated out-of-pocket costs of A$0.3 per capsule. Participants were more willing to continue and carry the costs if fewer capsules would have to be taken daily (garlic-1 and -2 versus garlic-4, P<0.05).

Blinding success was measured at the end of the trial by questionnaire. A third of the participants correctly guessed their allocation to either a garlic (33%) or placebo group (37%), whereas more than half of the participants were unsure of their allocation (58% garlic groups, 63% placebo), and 8% of participants in a garlic group incorrectly thought they had taken placebo capsules. A slightly greater proportion of participants in the garlic-4 group had guessed correctly, albeit differences between the groups were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our trial suggests aged garlic extract to be superior to placebo in lowering SBP in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. A dosage of two capsules daily containing 480 mg of aged garlic extract and 1.2 mg of S-allylcysteine significantly lowered SBP by mean SBP±s.e.=−11.8±5.4 mm Hg (P=0.006) compared with placebo over 12 weeks, was well tolerated and highly acceptable. The observed reduction in SBP is comparable to that achieved with commonly prescribed antihypertensive medicines, and is of clinical significance, whereby a reduction of about 10 mm Hg in SBP is associated with a risk reduction in cardiovascular disease by 16–40%.22, 23

The larger daily dosage of four capsules of aged garlic extract also lowered SBP, albeit the mean difference of SBP±s.e.=−7.4±4.1 mm Hg at 8 weeks compared with placebo was of borderline significance (P=0.07). The smaller reduction in SBP in the garlic-4 group compared with the garlic-2 group may have been linked to the poorer compliance and lesser tolerability seen in the garlic-4 group. A dosage of one capsule of aged garlic extract daily did not lower SBP significantly different to placebo.

In all, 4% of participants (3 out of 79) withdrew from the trial after 4 weeks because of gastrointestinal complaints, two in the garlic-4 group and one in the placebo-4 group. Although rare, gastrointestinal disturbances have been reported in other trials using therapeutic dosages of garlic by similar proportions of participants.10, 24, 25 Lower tolerance of sulphur-containing foods such as garlic and onion has been linked to genetic variation in detoxification pathways of sulphur-transferase enzymes, as well as inflammatory status, and levels of molybdenum and vitamin B12.26, 27

Other minor side effects were reported by a third (32%) of the participants in the garlic-4 group, and 15% in the garlic-2 and garlic-1 groups compared with 5% in the placebo group. Minor side effects included bloating, flatulence and reflux. However, most side effects were reported in the first week of the trial, and participants found ways to overcome these, for example, by taking the trial capsules in the morning rather than in the evening. Greater tolerability, compliance, acceptance and willingness to continue and pay for capsules were associated with a lower dosage and fewer capsules daily.

Our trial had limited power to detect any significant changes in DBP between the garlic groups and placebo, as participants were selected on the basis of systolic hypertension, subsequently including <13% of participants with essential hypertension (DBP >90 mm Hg; 5–20% in each group). A trend towards greater reduction in DBP was observed in the garlic-2 groups compared with placebo (mean diff. DBP±s.e.: −5.3±4.2 mm Hg), albeit not statistically significant. Our trial was also underpowered to undertake meaningful analysis by type of BP medication, complicated by the number and combination of antihypertensives possible.

The results of this trial are in line with our previous findings of aged garlic extract being effective in reducing SBP in hypertensives.10 Here we demonstrate that a daily dosage of two capsules of the high potency formula of aged garlic extract is effective and more practical than a daily dosage of four capsules. Furthermore, our findings indicate that a dosage of one capsule of high potency formula was not sufficient to reduce effectively SBP, highlighting the importance of correct dosing and choice of product formulation.

Dosage of the active ingredient S-allylcysteine in aged garlic extract is crucial to effectiveness in reducing BP, and needs to be reviewed when comparing results to other trials testing garlic products.8, 9

Our trial tested the effect of aged garlic extract as an adjunctive antihypertensive treatment in a mainly older population (mean age 70±12 years). It would be interesting to explore the effectiveness in other age groups with uncontrolled, treated or untreated hypertension.

In about 30% of participants, SBP did not waver for more than 5 mm Hg during the course of the trial, suggesting an underlying unresponsiveness to antihypertensive treatment. Future trials could explore potential underlying factors, such as genetic variations in the aldosterone synthase gene/enzyme pathway, which has been suggested to influence the response to antihypertensive treatment.28, 29

Larger trials are required to explore any effect of other antihypertensive medicines that patients are already taking on the effectiveness of adjunct therapy with aged garlic extract. It would also be interesting to explore the effect of aged garlic extract on other cardiovascular risk factors and the influence of standard drug therapy on its effectiveness. Moreover, long-term trials would provide insights into the effect of aged garlic extract on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

In summary, our trial suggests aged garlic extract to be an effective and tolerable treatment in uncontrolled hypertension, and may be considered as a safe adjunct treatment to conventional antihypertensive therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients, general practices, doctors and staff for their participation in the trial. We are grateful to our research nurse, Karen Bellchambers, who was instrumental in liaising with practices and patients and collecting data. We thankfully acknowledge statistical advice by Dr Nancy Briggs and Thomas Sullivan. This trial was supported by a Royal Adelaide Hospital New Investigator Clinical Project Grant (11RAHRC-7360). KR was supported by the Australian Government-funded Primary Health Care Research Evaluation and Development (PHCRED) Programme. Trial capsules were provided by Vitaco Health Ltd, Sydney, Australia, which was not involved in study design, data collection, analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors conceptualised the study and oversaw data collection. KR undertook data analysis and interpretation in discussion with biostatisticians. KR prepared the manuscript with contributions from co-authors. All authors approved the final version.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniuk AL, Lee CM, Lawes CM, Ueshima H, Suh I, Lam TH, et al. Hypertension: its prevalence and population-attributable fraction for mortality from cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hypertens. 2007;25:73–79. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328010775f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briganti EM, Shaw JE, Chadban SJ, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, McNeil JJ, et al. Untreated hypertension among Australian adults: the 1999–2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study. Med J Aust. 2003;179:135–139. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen H, Klemetsrud T, Stokke HP, Tretli S, Westheim A. Adverse drug reactions in current antihypertensive therapy: a general practice survey of 2586 patients in Norway. Blood Press. 1999;8:94–101. doi: 10.1080/080370599438266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:331–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MJ, Stewart RL, Merry H, Johnstone DE, Cox JL. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2003;145:806–812. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00084-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh GY, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried K, Frank OR, Stocks NP, Fakler P, Sullivan T. Effect of garlic on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2008;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart KM, Coleman CI, Teevan C, Vachhani P, White CM. Effects of garlic on blood pressure in patients with and without systolic hypertension: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1766–1771. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ried K, Frank OR, Stocks NP. Aged garlic extract lowers blood pressure in patients with treated but uncontrolled hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Maturitas. 2010;67:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LD, Gardner CD. Composition, stability, and bioavailability of garlic products used in a clinical trial. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:6254–6261. doi: 10.1021/jf050536+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino T, Kashimoto N, Kasuga S. Effects of garlic preparations on the gastrointestinal mucosa. J Nutr. 2001;131:1109S–1113SS. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.1109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harauma A, Moriguchi T. Aged garlic extract improves blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats more safely than raw garlic. J Nutr. 2006;136:769S–773SS. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.769S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macan H, Uykimpang R, Alconcel M, Takasu J, Razon R, Amagase H, et al. Aged garlic extract may be safe for patients on warfarin therapy. J Nutr. 2006;136:793S–795SS. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.793S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qattan KK, Thomson M, Al-Mutawa'a S, Al-Hajeri D, Drobiova H, Ali M. Nitric oxide mediates the blood-pressure lowering effect of garlic in the rat two-kidney, one-clip model of hypertension. J Nutr. 2006;136:774S–776SS. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.774S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro C, Lorenzo AG, Gonzalez A, Cruzado M. Garlic components inhibit angiotensin II-induced cell-cycle progression and migration: involvement of cell-cycle inhibitor p27(Kip1) and mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:781–787. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsuna K. Isolation and characterization of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor dipeptides derived from Allium sativum L. (garlic) J Nutr Biochem. 1998;9:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- PEN Computer Systems Pty Ltd, Parramatta, NSW, Australia. Available at http://www.clinicalaudit.com.au/ .

- Kyolic Garlic High Potency Everyday Formula 112 Wagner, Vitaco Health (NZ) Ltd, Sydney, Australia. Available at http://www.wagnerproducts.com.au/products-and-supplements/product-list/product-details/_prod_/Kyolic-High-Potency-Everyday-Formula .

- Ried K, Frank OR, Stocks NP. Dark chocolate or tomato extract for prehypertension: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes GT. Lowering blood pressure for cardiovascular risk reduction. J Hypertens Suppl. 2005;23:S3–S8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000165622.34192.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck E, Gruenwald J. Allium sativum in der Stufentherapie der Hyperlipidaemie. Med Welt. 1993;44:516–520. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli F, Capasso R, Izzo AA. Garlic (Allium sativum L.): adverse effects and drug interactions in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:1386–1397. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring RH, Klovrza LZ, Harris RM. Diet and individuality in detoxification. J Nutr Environ Med. 2007;16:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Meletis CD. Cleansing of the human body. A daily essential process. Altern Complement Therap. 2001;7:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Taverne K, de Groot M, de Boer A, Klungel O. Genetic polymorphisms related to the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and response to antihypertensive drugs. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6:439–460. doi: 10.1517/17425250903571670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiglia E, Tikhonoff V, Mazza A, Rynkiewicz A, Limon J, Caffi S, et al. C-344T polymorphism of the aldosterone synthase gene and blood pressure in the elderly: a population-based study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1991–1996. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000183119.92455.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]