Abstract

During DNA repair by HR (homologous recombination), the ends of a DNA DSB (double-strand break) must be resected to generate single-stranded tails, which are required for strand invasion and exchange with homologous chromosomes. This 5′–3′ end-resection of the DNA duplex is an essential process, conserved across all three domains of life: the bacteria, eukaryota and archaea. In the present review, we examine the numerous and redundant helicase and nuclease systems that function as the enzymatic analogues for this crucial process in the three major phylogenetic divisions.

Abbreviations: BLM, Bloom’s syndrome protein; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; Chi, crossover hotspot initiator; CtIP, CtBP (C-terminal-binding protein)-interacting protein; DSB, double-strand break; HR, homologous recombination; NHEJ, non-homologous end-joining; RPA, replication protein A; Sbc, suppressors of RecBC; SMC, structural maintenance of chromosomes

HR (homologous recombination) and the repair of DNA DSBs (double-strand breaks)

In all organisms, the maintenance and propagation of genetic material is a prerequisite for life. Cells have evolved numerous and complex DNA-repair pathways to ensure that genomic integrity is preserved. Failure to detect and faithfully repair chromosomal damage leads to genomic instability and consequential loss of cellular viability. Indeed, in humans, defects in DNA-repair pathways have been associated with developmental, immunological or neurodegenerative diseases and predispositions to cancer.

Throughout the cell cycle, genomic DNA is damaged by a variety of exogenous and endogenous agents. Compounds such as ROS (reactive oxygen species), generated during normal cellular metabolism, and environment hazards, such as ionizing radiation or chemical mutagens, constantly challenge the chromosomal integrity of cells. However, because of the highly efficient nature of the multiple and overlapping DNA repair mechanisms available to cells, the vast majority of the resultant DNA lesions are accurately repaired and do not lead to mutation.

The DSB, when both strands of the DNA duplex are simultaneously broken, is an especially cytotoxic form of damage. The resultant free DNA ends may be subject to illegitimate recombination or ligation, and these processes can lead to chromosomal rearrangements. Cells have consequently evolved numerous and redundant DSB-repair mechanisms, to faithfully restore the genetic sequence at the breaks and maintain genomic stability. The two predominant and intensely studied DNA DSB-repair mechanisms are NHEJ (non-homologous end-joining) and HR. In NHEJ, the two ends of the break are joined together with minimal DNA end-processing. Although this mechanism is incredibly fast and efficient, it is also highly error-prone and can often lead to mutations, such as deletions and chromosomal translocations (reviewed in [1]). In contrast, HR is a high-fidelity mechanism, using a chromosomal homologue as a template for the repair, and involves the extensive end-resection of the break. Although HR is a more accurate mode of repair than NHEJ, the requirements for a homologous template restrict this process to the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle (reviewed in [2]).

An essential step during HR-mediated repair is the extensive 5′–3′ end resection of the DSB. This process generates 3′ single-strand tails, which are bound by the RecA/Rad51/RadA family of recombinases to form the nucleoprotein filament that initiates HR. These presynaptic molecules invade homologous chromosomes to produce hybrid joint molecules. HR can then proceed by a variety of mechanisms involving DNA synthesis, branched molecule resolution and ligation (reviewed in [3]). The DNA end-resection step is a conserved process, observed in all three domains of life, and is dependent on specialized helicases and nucleases, often functioning in multiple and redundant pathways. Although some DNA-resection enzymes are specialized within a particular phylogenetic division, other components are crucial in all forms of life.

Bacteria: the fundamentals of DNA end-resection

The tripartite RecBCD helicase–nuclease complex of Escherichia coli is the best experimentally characterized DNA end-processing machinery, and is conserved across the majority of Gram-negative bacteria. A combination of biochemical, single-molecule, structural and genetic studies have provided insights into the mechanism of 3′ single-strand tail generation by this complex (reviewed in [4,5]). The DNA-unwinding activity of the complex is driven by the RecB and RecD helicase subunits [6,7] that translocate on the opposite strands of the DNA duplex, but act with complementary polarities, ensuring that the components of the complex migrate in the same direction [6,7] (Figure 1A). The nuclease domain of the complex is housed at the C-terminus of RecB, and its activity is regulated by the RecC subunit, via interaction with the conserved Chi (crossover hotspot initiator [8]) sequences, dispersed throughout the genome [9,10]. The current model of RecBCD end-resection, based on structural and biochemical evidence, proposes that the genomic Chi sites modulate the mode of DNA degradation by the complex. Before encountering a Chi site, this highly processive enzyme can destroy both strands of the duplex, although cuts are introduced more frequently on the 3′ strand, relative to the 5′ strand. However, upon encountering a Chi site, the complex stops digesting the 3′ strand, while the frequency of cutting on the 5′ strand increases [11]. In addition, after Chi site recognition, the nuclease module of RecB also facilitates loading of the RecA recombinase on to the 3′ strand, concurrent with the 5′ strand resection, thus aiding the formation of the nucleoprotein filament [5,12–14]. Interestingly, under different experimental conditions the RecBCD complex appears to act primarily as DNA translocase, only introducing an endonucleolytic cut when encountering a Chi site [4]. The complex then continues along the template loading RecA on to the cut strand to generate a 3′ nucleoprotein filament. There is current debate as to which of the two observed mechanisms is relevant in vivo. Although the first model, involving significant DNA resection is favoured, the second model of DNA translocation, nicking and unwinding has been shown to be consistent with some genetic data [4]. However, further support for the resection model has been provided by a recent analysis, which reveals insights into how Chi sites regulate the activity of the RecBCD complex. An α-helix located within the RecC subunit, which mediates the sequence-specific recognition of Chi elements, appears to allosterically regulate the positioning of a molecular ‘latch’, formed from other structural elements within RecC. Upon interaction with Chi, movement of the recognition helix alters the conformation of this latch to an ‘open’ arrangement, allowing the 3′ DNA strand to bypass the RecB nuclease domain, and exit undigested from the complex to permit the formation of the 3′ single-strand tail [15].

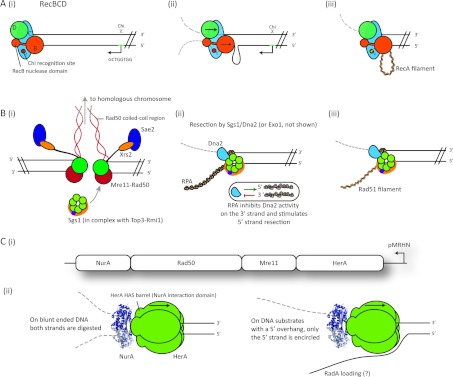

Figure 1. End-resection of DSBs in the three domains of life.

(A) The bacterial RecBCD pathway (E. coli). (i) DNA end recognition by the RecBCD helicase–nuclease complex. (ii) The two DNA strands are translocated separately by the helicases RecD (green, 5′–3′ polarity) and RecB (orange, 3′–5′ polarity). The nuclease domain is located at the C-terminus of RecB. Before encountering a Chi site, the 3′ strand is cleaved more frequently than the 5′ strand. A loop of single-stranded DNA accumulates ahead of RecB, as a result of the higher translocation rate of RecD. (iii) After Chi recognition by the RecC subunit (blue), the nuclease activity of the complex is stimulated on the 5′ strand and suppressed on the 3′ strand. RecB mediates RecA loading on to the resulting 3′ single-stranded DNA tail. (B) The eukaryotic Dna2–Sgs1 complex pathway (S. cerevisiae). (i) DNA end recognition and limited processing by the MRX complex (Mre11, green; Rad50, red; Xrs1, orange; Sae2, purple). (ii) MRX recruits the Sgs1 helicase (light green, in complex with Top3-Rmi1) to the DSB end. Extensive end-resection is performed by the Dna2 exonuclease (blue) in association with the Sgs1 helicase, or is alternatively processed by the Exo1 nuclease (not shown). RPA bound to the unwound single–strands stimulates Dna2 activity on the 5′ strand, and inhibits 3′ strand degradation (inset). (iii) RPA is subsequently replaced by the Rad51 recombinase on the 3′ tail. (C) The archaeal HerA–NurA helicase–nuclease pathway (S. solfataricus). (i) Operon encoding the herA, mre11, rad50 and nurA genes. (ii) Either one or two strands of the duplex can pass through the core of the complex, resulting in either the single-stranded resection (right), or wholesale destruction of both strands (left). NurA dimer (blue); HerA hexamer (green). Mre11 and Rad50 may be involved in the initial processing of the break and the recruitment of HerA–NurA.

In Gram-positive bacterial species, alternative helicase–nuclease complexes, analogous to RecBCD, have been identified. In Bacillus subtilis, the AddAB heterodimer fulfils the end-resection role, switching from a double-stranded DNA destruction mode, to a single-strand resection mode at Chi sequences specific to the B. subtilis genome [16–18]. Indeed, RecBCD-null mutants in E. coli can be functionally complemented by B. subtilis AddAB, restoring cell fitness, reversing the reduction in the rates of HR, and ablating sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents of the mutants [19,20]. Homologues of AddAB, known as RexAB have also been observed experimentally in Lactococcus lactis and Streptococcus pneumoniae [20,21]. The AddA subunit of the complex displays some sequence homology with RecB, and harbours both helicase and nuclease domains at the N and C-termini respectively, whereas a second nuclease domain is located at the C-terminus of AddB. Interestingly, the AddB subunit also displays some predicted structural resemblance to RecC, and is therefore thought to be responsible for Chi site recognition. The presence of two independent nuclease domains within the enzyme suggests that, unlike RecBCD, the two DNA strands are processed separately by these two distinct modules [22].

Another DNA end-resection complex, known as AdnAB, has been identified in mycobacterial species, which lack RecBCD or AddAB/RexAB homologues [23]. In a further variation on the theme of the RecBCD and AddAB end-resection assemblies, it was revealed that both the AdnA and AdnB components contain an N-terminal helicase domain, and a RecB-like C-terminal nuclease domain. In contrast with the RecBCD and AddAB enzymes, both the AdnA and AdnB motor domains appear to track on the same DNA strand together in a 3′–5′-direction, alongside the AdnB nuclease domain [24]. In contrast, the AdnA nuclease domain travels on the opposite strand and is responsible for 5′–3′ end-resection [24]. This has led to speculation that the motor domain in AdnA may act as the Chi site-detection module, in a role analogous to that of AddB [24,25].

Genetic studies of RecBCD mutants in E. coli have also led to the discovery of an auxiliary bacterial DNA end-resection pathway dependent on the RecQ helicase and RecJ exonuclease [26–31]. In this pathway, the RecJ exonuclease resects the 5′ strand, after the RecQ helicase unwinds the duplex template. The mechanism is dependent on the RecFOR recombination mediator complex, which loads the RecA recombinase on to the 3′ tail, generating the nucleofilament for strand invasion. Interestingly, multiple RecQ homologues are observed in the eukaryotic domain, where they play key roles in DNA-end resection and Holliday junction resolution. Indeed, mutations in the human RecQ homologues are associated with genomic instability and genetic diseases, such as Bloom's and Rothmund–Thomson syndromes (reviewed in [32]).

Eukaryotes: complex variations on the basic theme

The DNA end-resection process is also crucial for HR in the eukaryotic domain, and there are clear mechanistic similarities to the bacterial systems. A series of recent studies have significantly advanced our understanding of how the multiple and redundant eukaryotic pathways function to facilitate this fundamental process [33–43].

A key regulator in the eukaryotic end-resection pathway is the MRX/N complex (see Figure 1B). The core of this complex comprises a dimer of the highly conserved Mre11 nuclease, which associates tightly with a dimer of the Rad50 protein, a member of the SMC (structural maintenance of chromosomes) superfamily (reviewed in [44–46]). Rad50 is a split ABC (ATP-binding cassette)-type ATPase with a long coiled-coil insert nearing a zinc hook motif at its tip. Intermolecular binding between Rad50 molecules is possible via the zinc hook region, allowing Rad50 complexes to tether homologous chromosomes, facilitating HR [47]. The third, more divergent, component known as Xrs2 in yeast, or Nbs1 in vertebrates, is monomeric and possesses a FHA (forkhead-associated) domain that mediates the interaction of the MRX/N complex with other DNA-repair proteins following their DNA-damage-dependent phosphorylation (reviewed in [44,48]) (Figure 1B). The MRX/N complex is one of the first recruits to sites of DNA damage, where it is found in association with the eukaryotic DNA-repair protein Sae2/CtIP [CtBP (C-terminal-binding protein)-interacting protein], which is recruited to the complex via an association with Xrs2/Nbs1 upon phosphorylation [49–52]. In conjunction with Sae2/CtIP, MRX/N has been shown to initiate limited processing of DSBs in the early stages of end-resection [35,38,53,54].

The Mre11–Rad50 tetramer is conserved in all three domains of life, and in bacteria these components are known as SbcD and SbcC respectively. These proteins were originally identified as recombination deficiency suppressor mutations in E. coli RecBC mutants [Sbc (suppressors of RecBC)] [55,56], suggesting that the products of SbcCD processing result in illegitimate repair in the absence of a functional RecBCD helicase–nuclease complex [57]. In both the bacterial and eukaryotic domains, the complex has been shown to possess an Mre11 (SbcD)-dependent endonuclease activity that cleaves DNA ends blocked by covalently bound proteins and hairpin structures. This has led to the speculation that a major role of the complex may be to generate ‘clean’ ends at the break site, suitable for the recruitment of the resection machinery [41,58–60]. The structural and functional conservation of the Mre11/Rad50 (SbcD/SbcC) complex across all three domains of life is indicative of the essential roles that these proteins play in maintaining genomic stability.

After the initial limited processing of eukaryotic DSBs by the combined action of the MRX and Sae2 proteins, long-range end-resection is required in preparation for Rad51 recombinase mediated-strand exchange. This second stage of end-resection is dependent upon the ExoI 5′–3′ exonuclease, or alternatively is reliant on the action of the Dna2 helicase–nuclease, working in conjunction with the Sgs1/BLM (Bloom's syndrome protein) helicase, a homologue of bacterial RecQ [33–43] (Figure 1B). Whereas the Exo1 nuclease pathway has been shown to function independently of the Sgs1/BLM helicase, it has also been demonstrated that human ExoI resection activity is dramatically stimulated by a physical association with BLM [36,37]. Interestingly, the single-strand-binding protein RPA (replication protein A) appears to modulate the nuclease activity of Dna2, stimulating the digestion of RPA-coated 5′ strands, but inhibiting 3′ strand degradation [40] (see Figure 1B). Following end-resection by either ExoI or Dna2 and Sgs1/BLM, eukaryotic recombination mediators such as BRCA2 (breast cancer early-onset 2) and Rad52 are required for the loading of the Rad51 recombinase on to the 3′ strands to produce the nucleoprotein filament, reminiscent of the action of the bacterial FOR mediator complex in the RecQ/RecJ end-resection pathway.

In eukaryotic cells, the balance between DSB break by HR and NHEJ is tightly associated with changes in the cell cycle, to ensure that HR mechanisms are restricted to S- and G2-phases when homologous templates are available. In G1-phase, when repair is primarily mediated by NHEJ, the DNA end-resection machinery is inhibited. CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases) orchestrate the phosphorylation of DSB-repair proteins, such as Sae2/CtIP which are central to this regulation [34,61–64]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the Ku complex, responsible for DNA end-binding in the NHEJ pathway, directly competes with the MRX/N complex and Exo1 for the free ends at DSBs [42,64–69]. Recently, the nuclease activity of the MRX/N complex has been implicated in removing Ku from DNA ends, permitting the initiation of the end-resection process [69]. It therefore seems plausible that the regulation of the MRX/N nuclease activity by the CDK-dependent phosphorylation of Sae2/CtIP, may be central to controlling the cell-cycle-dependent switch from NHEJ to HR.

Final consideration should be given to the tight compaction of the eukaryotic DNA duplex around the core histones, as this wrapping introduces a significant barrier to DNA end-resection. Addressing this issue, three independent studies have identified the Fun30 nucleosome-remodelling complex as the agent responsible for co-ordinating the long-range DNA end-resection with the remodelling of chromatin [70–72].

Archaea: common mechanisms and novel factors

It has been established that the archaeal proteins and complexes responsible for the fundamental processes of DNA replication, transcription, translation and recombination display clear homology with eukaryotic counterparts. This similarity is presumably indicative of a shared evolutionary derivation of these components in the two domains of life [73–75]. HR appears to be the prominent mechanism for DSB in the archaea, mediated by the Rad51 recombinase orthologue RadA [76]. Indeed, no archaeal homologues, or even functional analogues, of the NHEJ machinery have been identified to date.

Unusually, RecQ homologues are found in only a few archaeal species, and are largely absent from the crenarchaeal kingdom. It has been proposed that the Hel308 helicase, displaying homology with the metazoan PolQ/Mus308, may fulfil an function analogous to that of RecQ [77,78]. Hel308 has been implicated in the rescue of stalled replication forks, and the branch migration of recombination intermediates such as Holliday junctions, but it is currently unknown whether this helicase plays any role in the DNA end-resection process in archaea.

Mre11, Rad50 and Rad51 orthologues are represented in all archaeal genomes examined to date. In contrast, homologues of the helicases and nucleases responsible for end-resection in the eukaryotic and bacterial domains of life have not yet been identified in archaea. However, the discovery of a conserved DNA-repair-associated operon in the thermophilic archaea provided the first clues as to how archaea solve the end-resection problem. This operon, in addition to encoding the Mre11 and Rad50 proteins, harboured the genes for two novel proteins: HerA, a hexameric helicase of the FtSK superfamily, and NurA, a 5′–3′ exonuclease [79–82] (Figure 1C). It was therefore predicted that all four proteins would act together to generate the 3′ tails required for HR. This archaeal 5′ end-resection hypothesis was verified experimentally by an in vitro reconstitution of the proteins encoded in the Pyrococcus furiosus operon [83]. The study suggested that the archaeal Mre11–Rad50 complex generates short 3′ tails, by limited endonucleolytic digestion of the 5′ strand, which then appear to be extended by the HerA–NurA complex.

Further insights into the mechanisms of the HerA–NurA interaction, and DNA end-resection, have been provided by two recent studies, which determined the crystal structures of NurA from Sulfolobus solfataricus [84], and P. furiosus [85]. These structures revealed that NurA forms an obligate dimeric ring of RNAse-H like domains, with an active site contained in each subunit. It was also demonstrated that the dimer interacts with the HerA hexamer, with a stoichiometry of 2:6, presumably to form a closed- ring assembly [84]. Interestingly, the central cavity of the NurA dimer is too narrow to accommodate a B-form DNA dimer, but, following unwinding, there is sufficient space for the two single strands to be passed along the inside of each subunit. Furthermore, in vitro biochemical analyses demonstrated that the enzymatic activities of both HerA and NurA were dramatically stimulated upon complex formation [84]. It was also observed that the nature of the DNA end appeared to modulate the outcome of HerA–NurA processing. On blunt duplex DNA ends, both strands were encircled and translocated by the complex, whereas on substrates that possessed a 5′ single-stranded overhang, only one strand was threaded through the core of the complex [84] (Figure 1C). Thus it seems that HerA–NurA processing can result in either the double-stranded destruction or single-strand resection of duplex DNA, in a manner analogous to the action of bacterial RecBCD [84]. It still remains to be determined how the switch between the two modes might be regulated, and which mechanism is most significant in vivo. It is also currently unclear how the Mre11–Rad50 and HerA–NurA complexes co-operate to generate the 3′ single-stranded tails required for end-resection. A potential physical association between Mre11–Rad50 complex and HerA has been reported previously [86], but the molecular basis for this interaction has yet to be elucidated.

Concluding remarks

The general mechanism of DNA end-resection is essential to the process of HR-mediated repair, and is conserved in all three domains of life. Studies using experimentally tractable model organisms have helped to build a picture of how these crucial mechanisms operate to maintain genomic stability. Archaeal models have already provided valuable insights into the workings of the highly conserved Mre11–Rad50 complex [47,87–91]. Given the involvement of the Mre11–Rad50 complex in the archaeal HR-mediated DSB repair pathway, it is likely that further insights into the conserved DNA end-resection processes will be gained from forthcoming studies using archaeal and other model systems.

Funding

Research in the N.P.R. laboratory is funded by the Medical Research Council [Career Development Award G0701443]. Research in the L.P. laboratory in funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship Award in Basic Biomedical Sciences [grant number 08279/Z/07/Z]. Funding for open access charge: the Medical Research Council [grant number G0701443 (to N.P.R.)], the Wellcome Trust [grant number 08279/2/07/Z (to L.P.)] and the Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge.

References

- 1.Lieber M.R. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman J.R., Taylor M.R., Boulton S.J. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S. Nucleases and helicases take center stage in homologous recombination. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith G.R. How RecBCD enzyme and Chi promote DNA break repair and recombination: a molecular biologist's view. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:217–228. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillingham M.S., Kowalczykowski S.C. RecBCD enzyme and the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008;72:642–671. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillingham M.S., Spies M., Kowalczykowski S.C. RecBCD enzyme is a bipolar DNA helicase. Nature. 2003;423:893–897. doi: 10.1038/nature01673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor F., Smith G.R. RecBCD enzyme is a DNA helicase with fast and slow motors of opposite polarity. Nature. 2003;423:889–893. doi: 10.1038/nature01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam S.T., Stahl M.M., McMilin K.D., Stahl F.W. Rec-mediated recombinational hot spot activity in bacteriophage lambda. II. A mutation which causes hot spot activity. Genetics. 1974;77:425–433. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singleton M.R., Dillingham M.S., Gaudier M., Kowalczykowski S.C., Wigley D.B. Crystal structure of RecBCD enzyme reveals a machine for processing DNA breaks. Nature. 2004;432:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handa N., Yang L., Dillingham M.S., Kobayashi I., Wigley D.B., Kowalczykowski S.C. Molecular determinants responsible for recognition of the single-stranded DNA regulatory sequence, χ, by RecBCD enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:8901–8906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spies M., Bianco P.R., Dillingham M.S., Handa N., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C. A molecular throttle: the recombination hotspot chi controls DNA translocation by the RecBCD helicase. Cell. 2003;114:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchill J.J., Kowalczykowski S.C. Identification of the RecA protein-loading domain of RecBCD enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;297:537–542. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spies M., Kowalczykowski S.C. The RecA binding locus of RecBCD is a general domain for recruitment of DNA strand exchange proteins. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson D.G., Kowalczykowski S.C. The translocating RecBCD enzyme stimulates recombination by directing RecA protein onto ssDNA in a chi-regulated manner. Cell. 1997;90:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L., Handa N., Liu B., Dillingham M.S., Wigley D.B., Kowalczykowski S.C. Alteration of χ recognition by RecBCD reveals a regulated molecular latch and suggests a channel-bypass mechanism for biological control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:8907–8912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chédin F., Handa N., Dillingham M.S., Kowalczykowski S.C. The AddAB helicase/nuclease forms a stable complex with its cognate chi sequence during translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18610–18617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chédin F., Ehrlich S.D., Kowalczykowski S.C. The Bacillus subtilis AddAB helicase/nuclease is regulated by its cognate Chi sequence in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:7–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeeles J.T., Gwynn E.J., Webb M.R., Dillingham M.S. The AddAB helicase–nuclease catalyses rapid and processive DNA unwinding using a single Superfamily 1A motor domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2271–2285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kooistra J., Haijema B.J., Venema G. The Bacillus subtilis addAB genes are fully functional in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;7:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.el Karoui M., Ehrlich D., Gruss A. Identification of the lactococcal exonuclease/recombinase and its modulation by the putative Chi sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halpern D., Gruss A., Claverys J.P., El-Karoui M. RexAB mutants in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology. 2004;150:2409–2414. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeeles J.T., Dillingham M.S. A dual-nuclease mechanism for DNA break processing by AddAB-type helicase-nucleases. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha K.M., Unciuleac M.C., Glickman M.S., Shuman S. AdnAB: a new DSB-resecting motor-nuclease from mycobacteria. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1423–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.1805709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unciuleac M.C., Shuman S. Characterization of the mycobacterial AdnAB DNA motor provides insights into the evolution of bacterial motor-nuclease machines. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2632–2641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saikrishnan K., Yeeles J.T., Gilhooly N.S., Krajewski W.W., Dillingham M.S., Wigley D.B. Insights into Chi recognition from the structure of an AddAB-type helicase-nuclease complex. EMBO J. 2012;31:1568–1578. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horii Z., Clark A.J. Genetic analysis of the RecF pathway to genetic recombination in Escherichia coli K12: isolation and characterization of mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;80:327–344. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama K., Irino N., Nakayama H. The recQ gene of Escherichia coli K12: molecular cloning and isolation of insertion mutants. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 1985;200:266–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00425434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umezu K., Nakayama K., Nakayama H. Escherichia coli RecQ protein is a DNA helicase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:5363–5367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovett S.T., Kolodner R.D. Identification and purification of a single-stranded-DNA-specific exonuclease encoded by the recJ gene of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:2627–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handa N., Morimatsu K., Lovett S.T., Kowalczykowski S.C. Reconstitution of initial steps of dsDNA break repair by the RecF pathway of E. coli. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1234–1245. doi: 10.1101/gad.1780709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd R.G., Picksley S.M., Prescott C. Inducible expression of a gene specific to the RecF pathway for recombination in Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 1983;190:162–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00330340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachrati Z., Hickson I.D. RecQ helicases: suppressors of tumorigenesis and premature aging. Biochem. J. 2003;374:577–606. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gravel S., Chapman J.R., Magill C., Jackson S.P. DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2767–2772. doi: 10.1101/gad.503108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huertas P., Cortés-Ledesma F., Sartori A.A., Aguilera A., Jackson S.P. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature. 2008;455:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature07215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mimitou E.P., Symington L.S. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nimonkar V., Ozsoy A.Z., Genschel J., Modrich P., Kowalczykowski S.C. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:16906–16911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809380105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nimonkar V., Genschel J., Kinoshita E., Polaczek P., Campbell J.L., Wyman C., Modrich P., Kowalczykowski S.C. BLM–DNA2–RPA–MRN and EXO1–BLM–RPA–MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev. 2011;25:350–362. doi: 10.1101/gad.2003811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Z., Chung W.H., Shim E.Y., Lee S.E., Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niu H., Chung W.H., Zhu Z., Kwon Y., Zhao W., Chi P., Prakash R., Seong C., Liu D., Lu L., et al. Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2010;467:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cejka P., Cannavo E., Polaczek P., Masuda-Sasa T., Pokharel S., Campbell J.L., Kowalczykowski S.C. DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature. 2010;467:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature09355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia V., Phelps S.E., Gray S., Neale M.J. Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1. Nature. 2011;479:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shim E.Y., Chung W.H., Nicolette M.L., Zhang Y., Davis M., Zhu Z., Paull T.T., Ira G., Lee S.E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 2010;29:3370–3380. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao S., Guay C., Toczylowski T., Yan H. Analysis of MRE11's function in the 5′→3′ processing of DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4496–4506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stracker T.H., Petrini J.H. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams R.S., Williams J.S., Tainer J.A. Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1 is a keystone complex connecting DNA repair machinery, double-strand break signaling, and the chromatin template. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;85:509–520. doi: 10.1139/O07-069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Amours D., Jackson S.P. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of DNA repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hopfner K.P., Craig L., Moncalian G., Zinkel R.A., Usui T., Owen B.A., Karcher A., Henderson B., Bodmer J.L., McMurray C.T., et al. The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair. Nature. 2002;418:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature00922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi J., Antoccia A., Tauchi H., Matsuura S., Komatsu K. NBS1 and its functional role in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair. 2004;3:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buis J., Stoneham T., Spehalski E., Ferguson D.O. Mre11 regulates CtIP-dependent double-strand break repair by interaction with CDK2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:246–252. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams R.S., Dodson G.E., Limbo O., Yamada Y., Williams J.S., Guenther G., Classen S., Glover J.N., Iwasaki H., Russell P., Tainer J.A. Nbs1 flexibly tethers Ctp1 and Mre11-Rad50 to coordinate DNA double-strand break processing and repair. Cell. 2009;139:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodson G.E., Limbo O., Nieto D., Russell P. Phosphorylation-regulated binding of Ctp1 to Nbs1 is critical for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1516–1522. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapman J.R., Jackson S.P. Phospho-dependent interactions between NBS1 and MDC1 mediate chromatin retention of the MRN complex at sites of DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:795–801. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicolette M.L., Lee K., Guo Z., Rani M., Chow J.M., Lee S.E., Paull T.T. Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1478–1485. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sartori A.A., Lukas C., Coates J., Mistrik M., Fu S., Bartek J., Baer R., Lukas J., Jackson S.P. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lloyd R.G., Buckman C. Identification and genetic analysis of sbcC mutations in commonly used RecBC sbcB strains of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1985;164:836–844. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.836-844.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibson F.P., Leach D.R., Lloyd R.G. Identification of sbcD mutations as cosuppressors of recBC that allow propagation of DNA palindromes in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:1222–1228. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1222-1228.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eykelenboom J.K., Blackwood J.K., Okely E., Leach D.R. SbcCD causes a double-strand break at a DNA palindrome in the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol. Cell. 2008;29:644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paull T.T., Gellert M. The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:969–979. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Connelly J.C., Kirkham L.A., Leach D.R. The SbcCD nuclease of Escherichia coli is a structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) family protein that cleaves hairpin DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:7969–7974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Connelly J.C., de Leau E.S., Leach D.R. Nucleolytic processing of a protein-bound DNA end by the E. coli SbcCD (MR) complex. DNA Repair. 2003;2:795–807. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aylon Y., Liefshitz B., Kupiec M. The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 2004;23:4868–4875. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ira G., Pellicioli A., Balijja A., Wang X., Fiorani S., Carotenuto W., Liberi G., Bressan D., Wan L., Hollingsworth N.M., et al. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004;431:1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jazayeri A., Falck J., Lukas C., Bartek J., Smith G.C., Lukas J., Jackson S.P. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Limbo O., Chahwan C., Yamada Y., de Bruin R.A., Wittenberg C., Russell P. Ctp1 is a cell-cycle-regulated protein that functions with Mre11 complex to control double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomita K., Matsuura A., Caspari T., Carr A.M., Akamatsu Y., Iwasaki H., Mizuno K., Ohta K., Uritani M., Ushimaru T., et al. Competition between the Rad50 complex and the Ku heterodimer reveals a role for Exo1 in processing double-strand breaks but not telomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5186–5197. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5186-5197.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wasko M., Holland C.L., Resnick M.A., Lewis L.K. Inhibition of DNA double-strand break repair by the Ku heterodimer in mrx mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair. 2009;8:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mimitou P., Symington L.S. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 2010;29:3358–3369. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Foster S.S., Balestrini A., Petrini J.H. Functional interplay of the Mre11 nuclease and Ku in the response to replication-associated DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:4379–4389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05854-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Langerak P., Mejia-Ramirez E., Limbo O., Russell P. Release of Ku and MRN from DNA ends by Mre11 nuclease activity and Ctp1 is required for homologous recombination repair of double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eapen V.V., Sugawara N., Tsabar M., Wu W.H., Haber J.E. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin remodeler Fun30 regulates DNA end-resection and checkpoint deactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:4727–4740. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00566-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Costelloe T., Louge R., Tomimatsu N., Mukherjee B., Martini E., Khadaroo B., Dubois K., Wiegant W.W., Thierry A., Burma S., et al. The yeast Fun30 and human SMARCAD1 chromatin remodellers promote DNA end resection. Nature. 2012;489:581–584. doi: 10.1038/nature11353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen X., Cui D., Papusha A., Zhang X., Chu C.D., Tang J., Chen K., Pan X., Ira G. The Fun30 nucleosome remodeller promotes resection of DNA double-strand break ends. Nature. 2012;489:576–580. doi: 10.1038/nature11355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barry R., Bell S.D. DNA replication in the archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:876–887. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bell S.D., Jackson S.P. Transcription and translation in archaea: a mosaic of eukaryal and bacterial features. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:222–228. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelman Z., White M.F. Archaeal DNA replication and repair. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.White M.F. Homologous recombination in the archaea: the means justify the ends. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011;39:15–19. doi: 10.1042/BST0390015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fujikane R., Komori K., Shinagawa H., Ishino Y. Identification of a novel helicase activity unwinding branched DNAs from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12351–12358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guy P., Bolt E.L. Archaeal Hel308 helicase targets replication forks in vivo and in vitro and unwinds lagging strands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3678–3690. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Constantinesco P., Forterre P., Elie C. NurA, a novel 5′-3′ nuclease gene linked to rad50 and mre11 homologs of thermophilic archaea. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:537–542. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Constantinesco P., Forterre P., Koonin E.V., Aravind L., Elie C. A bipolar DNA helicase gene, herA, clusters with rad50, mre11 and nurA genes in thermophilic archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1439–1447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manzan A., Pfeiffer G., Hefferin M.L., Lang C.E., Carney J.P., Hopfner K.P. MlaA, a hexameric ATPase linked to the Mre11 complex in archaeal genomes. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:54–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iyer L.M., Makarova K.S., Koonin E.V., Aravind L. Comparative genomics of the FtsK-HerA superfamily of pumping ATPases: implications for the origins of chromosome segregation, cell division and viral capsid packaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5260–5279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hopkins B.B., Paull T.T. The P. furiosus mre11/rad50 complex promotes 5′ strand resection at a DNA double-strand break. Cell. 2008;135:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blackwood J.K., Rzechorzek N.J., Abrams A.S., Maman J.D., Pellegrini L., Robinson N.P. Structural and functional insights into DNA-end processing by the archaeal HerA helicase-NurA nuclease complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3183–3196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chae J., Kim Y.C., Cho Y. Crystal structure of the NurA–dAMP–Mn2+complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2258–2270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Quaiser A., Constantinesco F., White M.F., Forterre P., Elie C. The Mre11 protein interacts with both Rad50 and the HerA bipolar helicase and is recruited to DNA following gamma irradiation in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. BMC Mol. Biol. 2008;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hopfner K.P., Karcher A., Craig L., Woo T.T., Carney J.P., Tainer J.A. Structural biochemistry and interaction architecture of the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11 nuclease and Rad50-ATPase. Cell. 2001;105:473–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams R.S., Moncalian G., Williams J.S., Yamada Y., Limbo O., Shin D.S., Groocock L.M., Cahill D., Hitomi C., Guenther G., et al. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell. 2008;135:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lammens K., Bemeleit D.J., Möckel C., Clausing E., Schele A., Hartung S., Schiller C.B., Lucas M., Angermüller C., Söding J., et al. The Mre11:Rad50 structure shows an ATP-dependent molecular clamp in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2011;145:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams J., Williams R.S., Williams J.S., Moncalian G., Arvai A.S., Limbo O., Guenther G., SilDas S., Hammel M., Russell P., Tainer J.A. ABC ATPase signature helices in Rad50 link nucleotide state to Mre11 interface for DNA repair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:423–431. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lim S., Kim J.S., Park Y.B., Gwon G.H., Cho Y. Crystal structure of the Mre11–Rad50–ATPγS complex: understanding the interplay between Mre11 and Rad50. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1091–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]