Abstract

While low health literacy and suboptimal medication adherence are more prevalent in racial/ethnic minority groups than Whites, little is known about the relationship between these factors in adults with diabetes, and whether health literacy or numeracy might explain racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes medication adherence. Previous work in HIV suggests health literacy mediates racial differences in adherence to anti-retroviral treatment, but no study to date has explored numeracy as a mediator of the relationship between race/ethnicity and medication adherence. This study tested whether health literacy and/or numeracy were related to diabetes medication adherence, and whether either factor explained racial differences in adherence. Using path analytic models, we explored the predicted pathways between racial status, health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, general numeracy and adherence to diabetes medications. After adjustment for covariates, African American race was associated with poor medication adherence (r=−0.10, p<0.05). Health literacy was associated with adherence (r=.12, p<0.02), but diabetes-related numeracy and general numeracy were not related to adherence. Furthermore, health literacy reduced the effect of race on adherence to non-significance, such that African American race was no longer directly associated with less medication adherence (r=−0.09, p=.14). Diabetes medication adherence promotion interventions should address patient health literacy limitations.

Keywords: Health literacy, numeracy, diabetes, medication adherence, disparities

In diabetes, suboptimal adherence to pharmacotherapy is associated with poor glycemic control (Rhee et al., 2005), increased risk of hospitalization, and mortality (Ho et al., 2006). African Americans are less adherent to their diabetes medications than Whites (Trinacty et al., 2009), and, as a result, have worse glycemic control than Whites (Heisler et al., 2007). The factors that explain racial disparities in diabetes medication adherence are unknown. One potential explanatory factor is health literacy, or one’s ability to understand, engage, and actively apply health information toward the goal of improving one’s health (IOM, 2004). Racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by low health literacy, with an estimated 41% of Hispanics, 24% of African Americans, and 9% of Whites having below basic health literacy skills (The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, National Center for Education Statistics. 2006).

Numeracy is the ability to understand and use numbers in daily life and, when inadequate, is associated with poor health outcomes (Rothman, Montori, Cherrington, & Pignone, 2008). While health literacy and numeracy are strongly correlated, there are patients with adequate health literacy who have poor numeracy (Rothman et al., 2006) and instances when numeracy, but not health literacy is related to outcomes (Cavanaugh et al., 2008; Huizinga, Beech, Cavanaugh, Elasy, & Rothman, 2008; Lokker et al., 2009). In diabetes, low health literacy and low numeracy have each been associated with worse diabetes knowledge, self-management behaviors, and glycemic control (Cavanaugh, et al., 2008; Schillinger et al., 2002). However, in the current sample of diabetes patients, diabetes-related numeracy, but not health literacy or general numeracy, explained the relationship between African American race and poor glycemic control (Osborn, Cavanaugh, Wallston, White, & Rothman, 2009). However, we did not test whether health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, or general numeracy were associated with diabetes medication adherence, and/or explained relationships between racial status and medication adherence or any other self-care activity.

In other chronic disease contexts, health literacy and numeracy have been associated with medication adherence and medication management, respectively; and have explained racial disparities in medication adherence and health outcomes. For example, health literacy was associated with adherence to antiretroviral medications and explained racial differences in self-reported adherence (Osborn, Paasche-Orlow, Davis, & Wolf, 2007). In another study, health literacy and numeracy were significantly related to the capacity to manage antiretroviral medications, but only numeracy explained the association between African American race and poor medication management (Waldrop-Valverde et al., 2009). Currently unknown is whether these relationships apply to medication adherence in diabetes.

We performed additional analyses on a dataset we have published from before (Cavanaugh, et al., 2008; Huizinga et al., 2008; Osborn, Cavanaugh, Wallston, & Rothman, 2010; Osborn, et al., 2009) to test whether racial status is associated with diabetes medication adherence, and whether health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, or general numeracy explain this relationship. We hypothesized that: (a) African Americans race would be associated with poor medication adherence; and (b) higher health literacy, higher diabetes-related numeracy, and higher general numeracy scores would be associated with medication adherence and explain the association between racial status and adherence.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participant recruitment, data collection procedures, and the majority of the measures used in our current analyses have been previously described (Cavanaugh, et al., 2008; Huizinga, Elasy, et al., 2008; Osborn, Cavanaugh, Wallston, et al., 2010; Osborn, et al., 2009). To prevent redundancy, we describe only our measure of diabetes medication adherence and new data analyses here.

Diabetes medication adherence

Diabetes medication adherence was assessed with the medication adherence subscale of the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire (Toobert, Hampson, & Glasgow, 2000). The medication adherence subscale of the SDSCA is a valid and reliable measure of adherence (Feil, Glasgow, Boles, & McKay, 2000; Toobert, et al., 2000), and individual items have correlated with objective measures of medication adherence (e.g., medication possession ratio, (Cohen, Shmukler, Ullman, Rivera, & Walker, 2010)).

Data Analyses

First, we tested for racial differences on demographic characteristics, as well as measures of health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, general numeracy, diabetes characteristics, diabetes medication adherence, and glycemic control. Independent samples t-tests were performed on continuous variables stratified by racial status (White or African American). Fisher’s exact tests with a one-sided significance level were performed on categorical variables.

Next, we performed a series of path analytic models using AMOS, version 19; a structural equation modeling program. We relied on the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean error of approximation (RMSEA) to assess model fit. CFI values that exceed 0.90 and RMSEA values below 0.08 indicate acceptable model fit; and RMSEA values close to 0.06 have been designated as indicative of “good fit” (Kline, 2004).

Hypotheses regarding the specific structural relations between variables in the model were evaluated through inspection of the direction and magnitude of the path coefficients. A path coefficient is a standardized regression coefficient (beta) showing the direct effect of one variable on another variable. When there are two or more variables, the path coefficient reflects the effect of one variable controlling for all other variables. Path coefficients may be decomposed into direct and indirect effects, corresponding to direct and indirect arrows in a path model. A direct effect occurs when variable A is significantly related to variable B, whereas an indirect effect occurs when variable C is related to variable A and a part of this relationship is transmitted to variable B (i.e., part of that “direct effect” is due to relations between A and C).

A series of path models were estimated with 383 cases; a sample size with adequate power for our estimated models (Kline, 2004; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996). Model 1 tested whether racial status was associated with diabetes medication adherence after controlling for age, gender, education, income, insulin use, diabetes type, and duration of diabetes. Model 2 tested whether health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, and general numeracy were associated with diabetes medication adherence; and, whether these variables explained any observed association between racial status and adherence. Finally, we created a parsimonious version of Model 2, dropping non-significant paths to diabetes medication adherence and performing a chi-square difference test against the full model for retention of the trimmed version.

Results

Participant Characteristics

During recruitment, 615 patients were referred for possible enrollment. Of these, 191 refused participation and 18 were excluded due to poor vision (n=7), age (n=4), non-English speaking (n=2), or other criteria (n=5). Of 406 patients that were consented, 398 (98%) completed the study. Only participants who reported being African American or White race (n=383; 96% of 398) were included in the current analyses. Characteristics of this sample are presented in Table 1. Mean age was 54 years; 50% were male, and 35% were African American. Fifty-six percent reported having greater than a high school education or equivalent, 31% had low health literacy according to the REALM, and 69% had low general numeracy according to the WRAT-3. The majority of participants (62%) were on insulin, and the mean (SD) HbA1c was 7.6% (1.7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by racial status.

| Characteristics | All Subjects | Racial Status | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | White Mean ± SD or n (%) |

African American Mean ± SD or n (%) |

||

| N | 383 | 249 | 134 | |

| Age (years) | 54.4 ± 13.0 | 54.4 ± 13.6 | 54.3 ± 12.0 | 0.97 |

| Female | 193 (50) | 107 (43) | 86 (64) | <0.001 |

| Income (n=375) | ||||

| < $20,000 | 166 (44) | 84 (35) | 82 (62) | <0.001 |

| ≥ $20,000 | 209 (56) | 159 (65) | 50 (38) | |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High School Grad/GED | 167 (44) | 90 (36) | 77 (58) | <0.001 |

| > High School Grad/GED | 216 (56) | 159 (64) | 57 (42) | |

| Insurance status (%yes) | ||||

| Private | 185 (48) | 135 (54) | 50 (37) | <0.001 |

| Public | 186 (49) | 112 (45) | 74 (55) | <0.03 |

| None | 6 (2) | 2 (.8) | 4 (3) | <0.11 |

| Literacy status, REALM | 58.9 ± 12.7 | 61.5 ± 10.3 | 54.0 ± 15.1 | <0.001 |

| < 9th grade | 120 (31) | 45 (18) | 75 (56) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 9th grade | 263 (69) | 204 (82) | 59 (44) | |

| General numeracy, WRAT-3 | 89.3 ±14.9 | 94.0 ± 13.0 | 80.6 ± 14.3 | <0.001 |

| < 9th grade | 266 (69) | 147 (59) | 119 (89) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 9th grade | 117 (31) | 102 (41) | 15 (11) | |

| Diabetes-related numeracy, DNT | 60.0 ± 0.24 | 69.0 ± 0.20 | 44.0 ± 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes: Type 2 (% yes) | 327 (85) | 199 (80) | 128 (95) | <0.001 |

| Years of diabetes | 11.3 ± 9.5 | 11.9 ± 10.1 | 10.3 ± 8.4 | 0.11 |

| Insulin use (% yes) | 236 (62) | 161 (65) | 75 (56) | 0.06 |

| BMI (n=377) (kg/m2) | 33.6 ± 8.1 | 32.7 ± 7.4 | 35.4 ± 9.2 | 0.002 |

| Medication adherence, SDSCA | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 0.04 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.6 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.5 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 0.005 |

Note: Groups were categorized by racial status and compared using independent samples t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test with a one-sided significance level for categorical variables. REALM=Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (Health literacy); WRAT-3=Wide Range Achievement Test-3rd edition (General numeracy); DNT=Diabetes Numeracy Test (Diabetes numeracy); BMI=Body Mass Index. The DNT score is the percent of correct items, with 24% of the sample being in the lowest DNT quartile (Osborn, et al., 2009). The SDSCA medication adherence subscale score is the number of days being adherent to diabetes medicines in the past seven days, of which 14% of the sample reported less than perfect adherence.

Compared to White participants, African American participants were more likely to be female, report annual incomes <20K, have less education, public health insurance, higher BMIs, be less adherent to diabetes medications (6.5 ± 1.3 vs. 6.8 ± 0.8; p=0.04), and have worse glycemic control (see Table 1). African American participants were also more likely to have low health literacy (<9th grade reading level), low diabetes-related numeracy, and low general numeracy compared to White participants.

Path Models

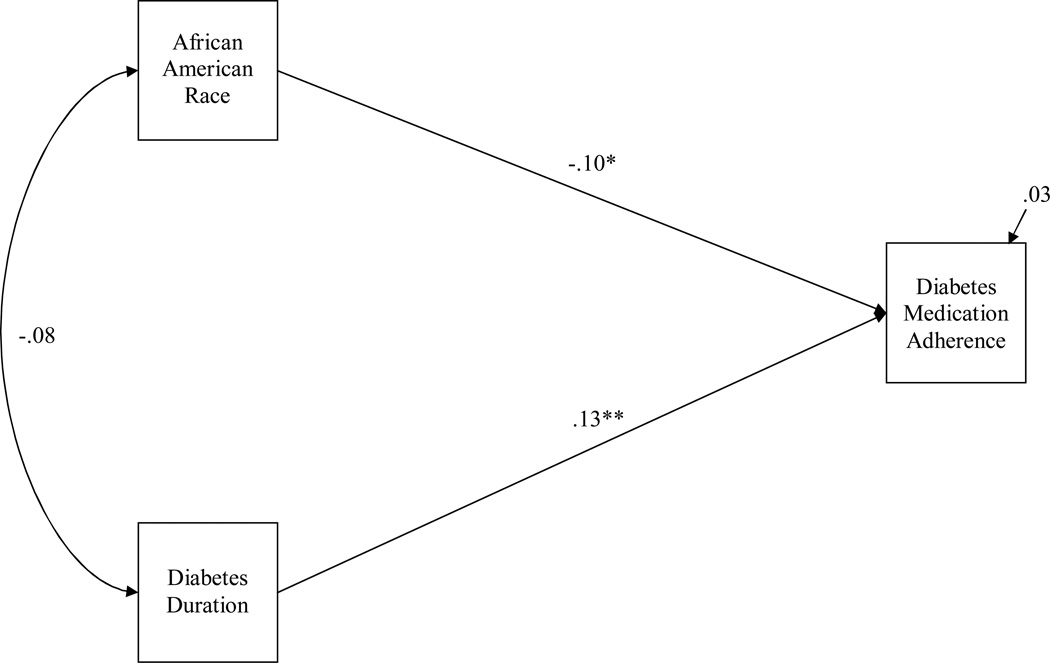

As shown in Figure 1, Model 1 included eight exogenous variables: age, gender, education, income, insulin use, diabetes type, duration of diabetes, and racial status (White or African American); and one endogenous variable: diabetes medication adherence. Examination of the path coefficients in this fully adjusted model showed marginal associations between African American race and less medication adherence (r=−0.09, p=0.10), and longer diabetes duration and greater medication adherence (r=0.10, p=0.10). Because the remaining exogenous variables were not associated with medication adherence (all p-values >0.40), these paths were dropped to create the most parsimonious model and to test the direct effect of African American race on medication adherence adjusting for diabetes duration only. As shown in Figure 1, after adjustment for diabetes duration, which had a direct effect on medication adherence (r=0.13, p<0.01), African American race was significantly associated with less medication adherence (r=−0.10, p<.05)

Figure 1.

African American race and diabetes duration predict diabetes medication adherence.

Note: Coefficients are standardized path coefficients. For tests of significance of individual paths, *p<.05 and **p<.01.

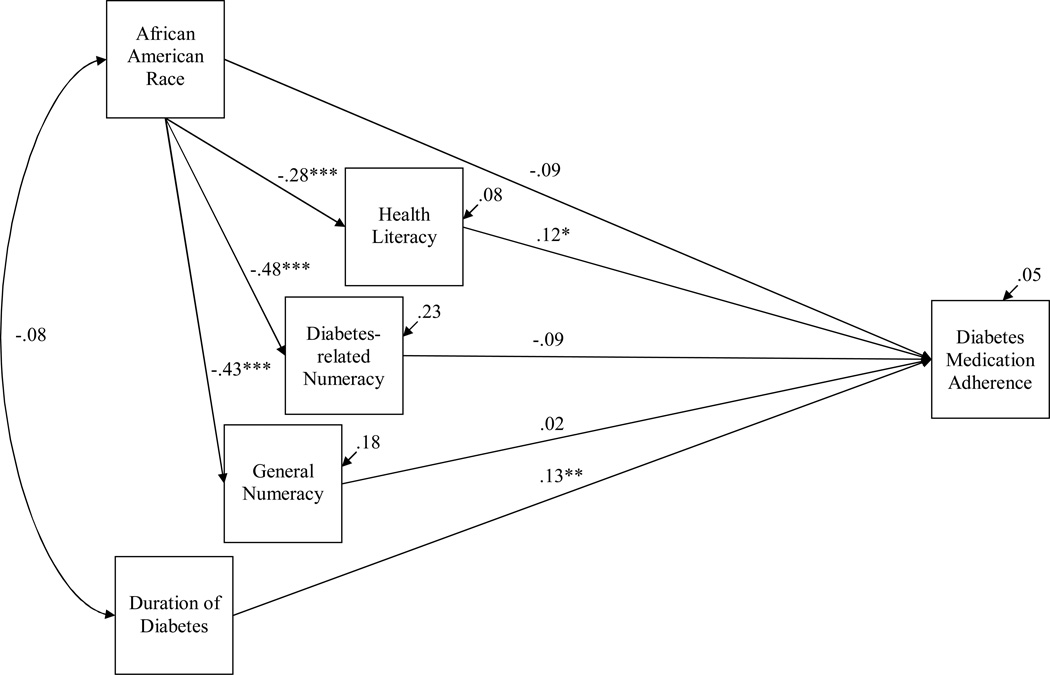

Model 2 (see Figure 2) tested whether health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, and general numeracy were associated with diabetes medication adherence; and, whether these variables explained the relationship between African American race and less medication adherence. Health literacy had a direct effect on medication adherence (r=.12, p<0.02), but diabetes-related numeracy and general numeracy were not related to diabetes medication adherence. Furthermore, health literacy reduced the effect of race on adherence to non-significance, such that African American race was no longer associated with less medication adherence (r=−0.09, p=.14).

Figure 2.

Health literacy reduces the race effect on diabetes medication adherence [full model].

Note: Coefficients are standardized path coefficients. For tests of significance of individual paths, *p<.05, **p<.01, and ***p<.001.

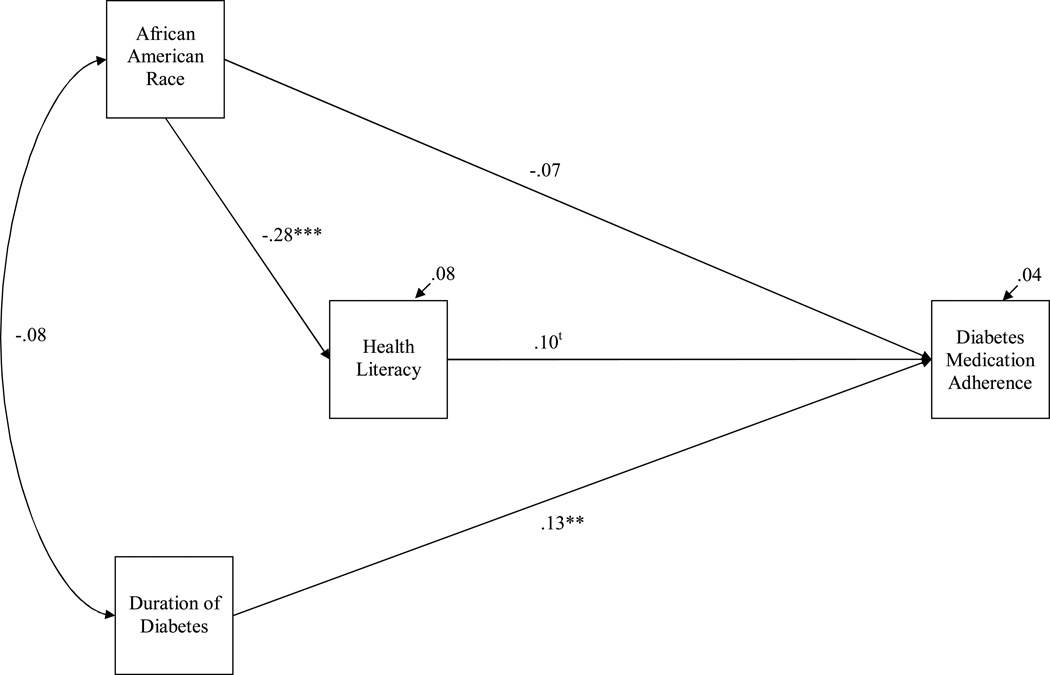

In an effort to create the most parsimonious model (see Figure 3), non-significant paths to diabetes medication adherence were dropped from Model 2. In this trimmed version of Model 2, African American race remained not significantly associated with diabetes medication adherence (r=−.07, p=.19), health literacy became marginally associated with adherence (r=.10, p=.06), and diabetes duration retained its direct effect on adherence (r=0.13, p<0.01). Furthermore, African American race had an indirect effect on diabetes medication adherence through health literacy (r=−.03, p<.01), suggesting health literacy explained the relationship between racial status and adherence. The estimated model produced excellent data fit: χ2 (2, N=383)=.08, p=.78; RMSEA= .00, 90% .00–.09; CFI = 1.00.

Figure 3.

Health literacy reduces the race effect on diabetes medication adherence [trimmed model].

Note: Coefficients are standardized path coefficients. For tests of significance of individual paths, tp=.06, *p<.05, **p<.01, and ***p<.001. Excellent model fit: χ2 (2, N=383)=.08, p=.78; RMSEA= .00, 90% .00–.09; CFI = 1.00.

Discussion

In our previous work, we reported health literacy was not related to glycemic control, and thus could not explain the association between racial status and glycemic control (Osborn, et al., 2009). Here, we performed additional analyses on the same dataset to test whether health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, and general numeracy are determinants of diabetes medication adherence, and could explain the association between racial status and adherence. Consistent with our hypothesis and prior work in the diabetes literature, African American race was associated with less adherence to diabetes medications after adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic covariates (Heisler, et al., 2007; Trinacty, et al., 2009). However, to our knowledge, this study is the first to report a relationship between low health literacy and less adherence to diabetes medications, and show that health literacy, but not diabetes-related numeracy or general numeracy, explains racial disparities in adherence.

Successful adherence to medications relies on the correct identification of medications, understanding the correct amount of medication to take at each dose, the timing of doses, determination of missed doses, need for refills and comprehension of warnings and other ancillary instructions (e.g., “take on an empty stomach”). Low health literacy is a risk factor for incorrect identification of medications (Kripalani et al., 2006), misinterpretation of drug label instructions (Davis, Wolf, Bass, Thompson, et al., 2006), and difficulty understanding drug label warnings (Davis, Wolf, Bass, Middlebrooks, et al., 2006). In addition, patients with low health literacy often rely upon verbal instructions about their medications, and yet report inadequate provider communication across domains critical to successful chronic disease care and self-management, including a how providers communicate about medications (Schillinger, Bindman, Wang, Stewart, & Piette, 2004). It is therefore not surprising that health literacy was associated with diabetes medication adherence in this study.

Diabetes-related numeracy and general numeracy were unrelated to our measure of diabetes medication adherence, and thus could not explain the association between African American race and less medication adherence. This was somewhat surprising, as the interpretation and application of quantitative information is an important part of medication management. This finding is also inconsistent with a study in HIV that showed an association between numeracy and medication management, with numeracy explaining the association between African American race and poor management of antiretroviral medications (Waldrop-Valverde, et al., 2009). We previously demonstrated that diabetes-related numeracy explained the association between African American race and poor glycemic control (Osborn, et al., 2009) and hypothesized this might in part be related to self-care behaviors. However, medication adherence is only one element of successful diabetes self-care. Other self-care activities, including dietary adherence, glucose monitoring, and participation in preventive health care services might be more strongly associated with numeracy than health literacy. In addition, few participants reported poor medication adherence, potentially limiting our ability to detect an association between numeracy and medication adherence in this study. Perhaps examination in a larger cohort of patients would yield additional information regarding the role of numeracy and medication adherence in diabetes.

Factors other than health literacy might also contribute to diabetes medication adherence. In our study, we also found diabetes duration was independently associated with adherence. Patients who have had diabetes for a longer time are probably more accustomed to taking medications on a regular basis and therefore report better adherence. This is similar to the relationship between advancing age and adherence (Gazmararian et al., 2006). Previous literature also suggests that socioeconomic status might explain observed racial disparities in diabetes status (Signorello et al., 2007), and might also be associated with poor adherence to diabetes medications (Trinacty, et al., 2009). Interestingly, in our study, we did not observe an association between income or years of education and medication adherence. This might be due to how we measured these variables, or it might be that health literacy represents a broad range of skills (IOM, 2004) more closely related to certain behaviors such as medication adherence.

There are study limitations to acknowledge. First, we assessed diabetes medication adherence via a single, validated self-report measure rather than using more objective measures of adherence (e.g., pill counts, prescription refills, electronic monitoring devices). While patients might under-report non-adherence through questionnaires, a handful of studies suggest self-report measures are viable and accurate measures of adherence (Gehi, Ali, Na, & Whooley, 2007; Schroeder, Fahey, Hay, Montgomery, & Peters, 2006). Second, our measure of health literacy, the REALM, while validated and considered one of the primary health literacy assessments, measures word-recognition and might not assess patient health literacy to the most specific level possible, particularly when compared to other health literacy assessments (Baker, 2006). Third, although path models propose a causal relationship between variables, the current study measured all variables cross-sectionally and, thus, can most appropriately speak to associations between variables observed at a single point in time, not causality. Future research is needed to investigate the longitudinal effects of these variables on changes in diabetes medication adherence over time. Fourth, although our path models adjusted for many potential confounding variables, there remains the possibility of residual confounding. Finally, this study excluded non-English speaking participants who are at high risk for low health literacy, medication non-adherence, and poor glycemic control. Despite these limitations, our study is the first to examine the role of health literacy, diabetes-related numeracy, and general numeracy in both predicting medication adherence in adults with diabetes and in explaining the relationship between racial status and diabetes medication adherence.

Low health literacy presents a wide-reaching barrier to disease control that, unlike race/ethnicity or socioeconomic reasons for non-adherence (e.g., cost, access, competing demands), can be easilly targeted to improve diabetes medication adherence. This is why our study has important implications, particularly with respect to educational efforts to promote diabetes medication adherence among patients of all health literacy levels. Efforts should include increasing the awareness of the impact of low health literacy and improving the training of providers in clear communication skills (Kripalani & Weiss, 2006); exercising clear health communication strategies (e.g., using plain language, the teach-back method, and education materials that are sensitive to low health literacy and low numeracy) when interacting with patients (Osborn, Cavanaugh, & Kripalani, 2010); and improving medication packaging, labeling, and dispensing (Davis, Wolf, Bass, Thompson, et al., 2006). Instructional and educational improvements such as these might help decrease racial disparities in diabetes medication adherence; and, ultimately, contribute to reducing disparities in the early development of diabetes complications and disease-related mortality.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded with support from the American Diabetes Association (Novo Nordisk Clinical Research Award), the Pfizer Clear Health Communication Initiative, and the Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center (NIDDK P60 DK020593). Dr. Osborn performed this research with the support of a Diversity Supplement Award (NIDDK P60 DK020593-30S2), and is currently supported by a K Award (NIDDK K01DK087894).

References

- Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh K, Huizinga MM, Wallston KA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Davis D, et al. Association of numeracy and diabetes control. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(10):737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HW, Shmukler C, Ullman R, Rivera CM, Walker EA. Measurements of medication adherence in diabetic patients with poorly controlled HbA(1c) Diabetic Medicine. 2010;27(2):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, Middlebrooks M, Kennen E, Baker DW, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):847–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil EG, Glasgow RE, Boles S, McKay HG. Who participates in Internet-based self-management programs? A study among novice computer users in a primary care setting. The Diabetes Educator. 2000;26(5):806–811. doi: 10.1177/014572170002600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian JA, Kripalani S, Miller MJ, Echt KV, Ren J, Rask K. Factors associated with medication refill adherence in cardiovascular-related diseases: a focus on health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(12):1215–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, Whooley MA. Self-reported medication adherence and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the heart and soul study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(16):1798–1803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: Department of Education; 2006. The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(17):1853–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, McClure DL, Plomondon ME, Steiner JF, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(17):1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga MM, Beech BM, Cavanaugh KL, Elasy TA, Rothman RL. Low numeracy skills are associated with higher BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(8):1966–1968. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, Cavanaugh K, Davis D, Gregory RP, et al. Development and validation of the Diabetes Numeracy Test (DNT) BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8:96. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):852–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Teaching about health literacy and clear communication. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):888–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokker N, Sanders L, Perrin EM, Kumar D, Finkle J, Franco V, et al. Parental misinterpretations of over-the-counter pediatric cough and cold medication labels. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1464–1471. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Kripalani S. Strategies to address low health literacy and numeracy in diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2010;28(4):171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, Rothman RL. Self-efficacy links health literacy and numeracy to glycemic control. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;2(15 Suppl):146–158. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, White RO, Rothman RL. Diabetes numeracy: an overlooked factor in understanding racial disparities in glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1614–1619. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Health literacy: an overlooked factor in understanding HIV health disparities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(5):374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee MK, Slocum W, Ziemer DC, Culler SD, Cook CB, El-Kebbi IM, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. The Diabetes Educator. 2005;31(2):240–250. doi: 10.1177/0145721705274927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, Davis D, Gregory R, Gebretsadik T, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(5):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, Montori VM, Cherrington A, Pignone MP. Perspective: the role of numeracy in health care. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13(6):583–595. doi: 10.1080/10810730802281791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;52(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(4):475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hay AD, Montgomery A, Peters TJ. Adherence to antihypertensive medication assessed by self-report was associated with electronic monitoring compliance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(6):650–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorello LB, Schlundt DG, Cohen SS, Steinwandel MD, Buchowski MS, McLaughlin JK, et al. Comparing diabetes prevalence between African Americans and Whites of similar socioeconomic status. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(12):2260–2267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinacty CM, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Meigs JB, Piette JD, et al. Racial differences in long-term adherence to oral antidiabetic drug therapy: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde D, Osborn CY, Rodriguez A, Rothman RL, Kumar M, Jones DL. Numeracy Skills Explain Racial Differences in HIV Medication Management. AIDS and Behavior. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]