Abstract

Adenosine is released in large amounts during myocardial ischemia and is capable of exerting potent cardioprotective effects in the heart. Although these observations on adenosine have been known for a long time, how adenosine acts to achieve its anti-ischemic effect remains incompletely understood. However, recent advances on the chemistry and pharmacology of adenosine receptor ligands have provided important and novel information on the function of adenosine receptor subtypes in the cardiovascular system. The development of model systems for the cardiac actions of adenosine has yielded important insights into its mechanism of action and have begun to elucidate the sequence of signalling events from receptor activation to the actual exertion of its cardioprotective effect. The present review will focus on the adenosine receptors that mediate the potent anti-ischemic effect of adenosine, new ligands at the receptors, potential molecular signalling mechanisms downstream of the receptor, mediators for cardioprotection, and possible clinical applications in cardiovascular disorders.

I. ADENOSINE RECEPTORS

Four subtypes of adenosine receptors, A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors, have been identified by molecular cloning [1, 2]. They all belong to the superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors and are characterized by seven hydrophobic membrane-spanning segments. The cloning and expression of recombinant adenosine receptors have been carried out in a number of species including chick, cow, dog, pig, rat, mouse, rabbit, sheep, as well as human [1], In a given species, coding sequence of a particular adenosine receptor derived from different tissues is similar or identical. Thus, it is likely, although not proven, that an adenosine receptor subtype is the same whether it is isolated from the brain, heart or lungs.

The adenosine A1 and A3 receptors are Gi- coupled receptors; their activation leads to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity and of cyclic AMP accumulation [3]. Whether the A1 or the A3 receptor is also coupled to other G protein is not known. However, it is known that the A1 receptor is also coupled to the atrial cardiac myocyte potassium channel (Kir) [4] and phospholipase C [5] although the βγ subunit of Gi is likely the mediator linking the adenosine A1 receptor and the Kir and phospholipase C. Recently, the A3 receptor has also been shown to mediate phospholipase D activation [5]. The identity of the G protein in coupling the A3 receptor to phospholipase D remains unknown.

The other two adenosine receptors, the adenosine A2A and A2B receptors, are coupled to Gs leading to stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity and cyclic AMP accumulation [6]. However, the coupling of A2 receptors is not limited to Gs. Thus, the A2B receptor is also potently coupled to Gq leading to a pronounced stimulation of phospholipase C [7]. The physiological response mediated by each receptor- effector, for example, the A1 receptor- phospholipase C, in a given tissue remains to be determined. The biological role of these specific receptor-effector interactions in the cardiovascular system remains an area of intense interest and deserves further investigation.

II. CHEMISTY AND PHARMACOLOGY OF ADENOSINE RECEPTOR LIGANDS

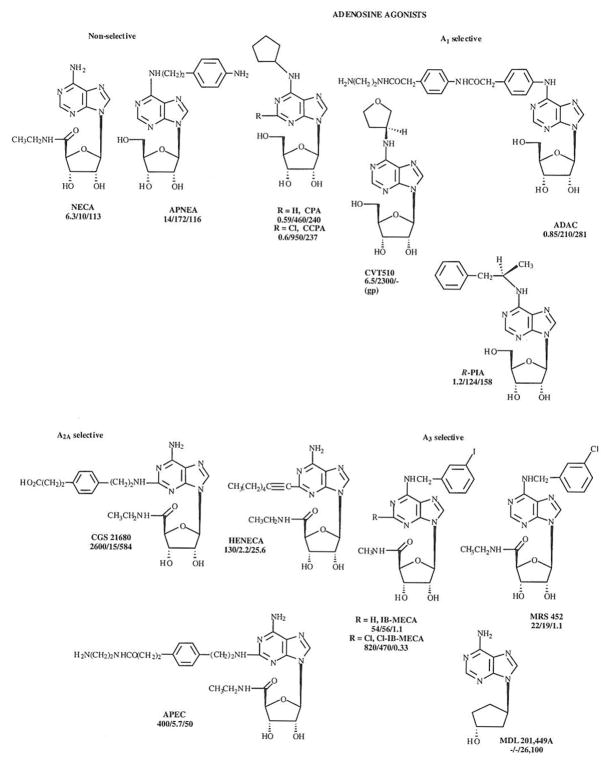

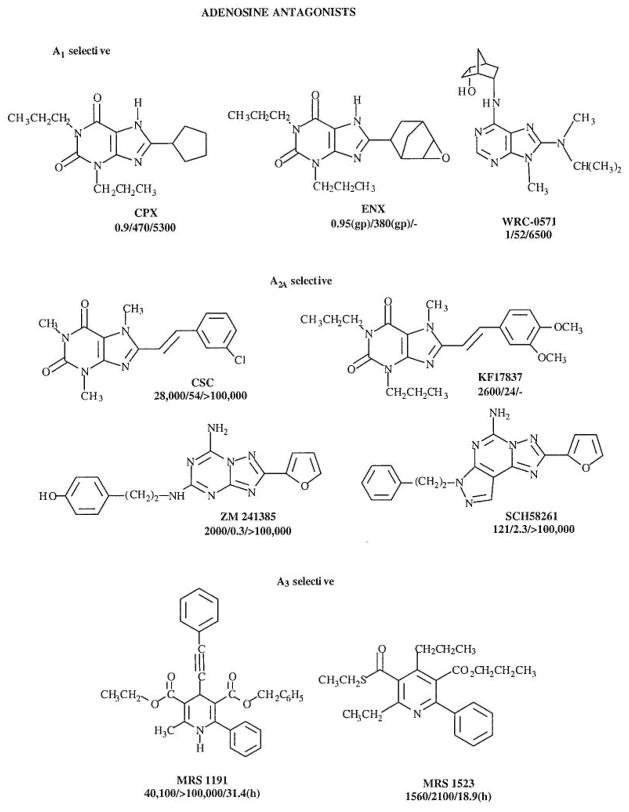

The structures and affinity of various agonists and antagonists are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Agonists at the various adenosine receptor subtypes. Non-selective as well as selective agonists are shown. Ki values, in nM, for A1, A2A and A3 receptors (rat, unless indicated) are shown in that order below the structure and name for each compound.

Fig. 2.

Antagonists at the various adenosine receptor subtypes. The structure and Ki values for adenosine receptor antagonists are shown. Ki values, in nM, for A1, A2A and A3 receptors (rat, unless indicated) are indicated in that order below the structure and name for each compound.

Non-selective Agonists

NECA (5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine) is among the most potent non-selective adenosine agonists and is still the most potent agonist reported at the A2B adenosine receptor subtype, for which there are no selective agonists. Previously, NECA has been used erroneously as an A2A-selective agonist [8]. Originally (1972) NECA was included in a patent filed by Abbott Laboratories for use in treating hypertension. As an adenosine analogue modified at the 5′-position of the ribose ring, NECA is not subject to phosphorylation by adenosine kinase.

APNEA (N6-(p-aminophenylethyl) adenosine has been used for the activation of A3 receptors [9], particularly in combination with A1-receptor selective antagonists, however it is non-selective, and other agonists highly selective for the A3 subtype are now available such IB-MECA (see below).

A1 Receptor Agonists

Numerous adenosine derivatives substituted at the N6-exocyclic amine with aryl, alkyl, or cycloalkyl groups have been found to selectively activate the A1 adenosine receptor subtype. Such modifications preclude inactivation by adenosine deaminase and thus greatly prolong the half-life in pharmacological systems. Among the earliest potent adenosine derivatives was R-PIA ((R)-N6- phenylisopropyladenosine), which is the chemical combination of adenosine and L-amphetamine (to form the phenylisopropyl group). In the late 1960’s, prior to the discovery of its mechanism of action, i.e. adenosine receptors, this compound was reported to be a potential hypotensive agent. It was tested in humans, but the clinical development was curtailed due to side effects. While the hypotensive effect of this agonist is related to its activation of A2A receptors, nevertheless, R-PIA is moderately selective for the A1 subtype. In fact, in tritiated form it was introduced in 1980 as one of the first radioligands shown to bind specifically to A1 adenosine receptors in the cerebral cortex [10]. R-PIA has been used as a selective A1 agonist for studies of cardioprotection [11], however even more selective A1 agonists are available and preferred, since in the heart the selectivity of A1 adenosine agonists is generally diminished with respect to binding affinities at A1/A2A receptors [12].

Among the more highly selective A1 agonists are CPA (N6-cyclopentyladenosine) and its 2-chloro analogue CCPA [13]. A homologous series of N6-cycloalkyl adenosine derivatives has been shown to be highly potent and selective at the A1 subtype [8], with optima occurring at cyclopentyl and cyciohexyl. Both CPA and CCPA have been used in various models of cardioprotection [14] and cerebroprotection [15], Chronic administration of CPA in mice was found to mimic some of the CNS effects of acute administration of an A1 selective antagonist [8], CVT510 (N6-((S)-3-tetrahydro-furanyl)adenosine) is an ether derivative structurally related to CPA, which is highly selective for the A1 receptor and has been proposed for the treatment of reentrant tachycardias that involve the A-V node [16].

N6-Phenyl substituted adenosine derivatives have been studied as receptor agonists. One such derivative, ADAC (adenosine amine congener, N6-[4-[[[4-[[[(2-aminoethyl)amino]carbonyl]methyl] anilino]carbonyl]methyl]phenyl-adenosine), was introduced in the mid 1980’s as a functionalized congener (i.e. it contains a primary amino group at the terminal position of a strategically placed elongated chain, thus allowing conjugation to carriers without losing receptor binding) with high affinity and selectivity for the A1 receptor subtype [17]. ADAC has been used as a chemical precursor for spectroscopic, e.g. fluorescently-labeled, probes of the A1 receptor. Also, its conjugation with bifunctional crosslinking reagents, such as p-phenylene diisothiocyanate (p-DITC), has resulted in irreversibly binding affinity labels for the A1 receptor in the heart [18]. Tritiated ADAC was shown to be a high affinity radioligand for the A1 receptor displaying minimal non-specific membrane binding, despite the presence of aromatic rings in the functionalized chain. ADAC is cardioprotective in a chick cardiac myocyte model of ischemia [19], and also cerebroprotective in a model of global ischemia [20]. Acute administration of ADAC at a very low dose range (25 – 100 μg/kg) was found to limit post-ischemic hippocampal damage in gerbils following bilateral carotid artery occlusion. Hemodynamic side effects of the adenosine agonist were minimal within this low dose range.

A1 Receptor Antagonists

DPCPX (or CPX, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine) was the first highly selective A1 antagonist to be introduced [8]. Tritiated DPCPX has been used widely as a high affinity radioligand for the A1 receptor. Although it is roughly 500-fold selective for the rat A1 vs A2A receptor, its use as an absolutely selective adenosine antagonist must be tempered by studies at the other two subtypes. The potency of DPCPX at A2B receptors and at human (but not rat) A3 receptors is intermediate (Ki values of approximately 30 and 75 nM, respectively) [21, 22], It should be noted that, in general, the A3 receptor affinity of most xanthines is highly species dependent, with the affinity at human receptors typically >100-fold greater than at rat receptors.

Curiously, DPCPX was found to have an unanticipated action in the promotion of chloride efflux in CFPAC cells, which contain a mutation of the CFTR chloride transporter (the F508) that occurs in cystic fibrosis [23]. DPCPX is in Phase II clinical trials by SciClone Pharmaceuticals for the treatment of cystic fibrosis, an action apparently not resultant from its A1 receptor antagonist properties.

ENX (1,3-dipropyl-8-[2-(5,6-epoxy)norbornyl] xanthine) is a conformationally constrained structural refinement of CPX. This xanthine is highly potent and extremely selective for A1 receptors in binding and functional assays [24], ENX is a racemic mixture and was subsequently resolved. The pure S-enantiomer, CVT 124 (S-1,3-dipropyl-8[2-(5,6-epoxynorbornyl)]xanthine), which is the more potent isomer, is selective for A1 receptors even with respect to the A2B receptor. It is under development by Biogen Corp. for cardiac and renal applications.

In pharmacological studies, many synthetic xanthine derivatives have proven difficult to dissolve in biological media, for example, the aqueous solubility of DPCPX at neutral pH is 30 μM.

In the search for novel adenosine antagonists, a number of classes of non-xanthine heterocycles, which are amenable to structural optimization as subtype-selective antagonists, have been identified. Among non-xanthine antagonists which have been explored are numerous 9-alkyladenine derivatives, such as WRC-0571 (Martin et al., 1996), developed by Discovery Therapeutics, which displays a high degree of selectivity for A1 vs. A3 receptors.

A2A Receptor Agonists

Many A2A agonists which are derivatized at the 2-position have been introduced. Perhaps the most widely used A2A-receptor selective agonist is CGS 21680 (2-[4-[(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine), which is modified at both 2- and 5′-positions (a NECA-like derivative). CGS 21680 has a Ki value of approximately 15 nM at both rat and human [26] A2A-receptors and was introduced originally for the treatment of hypertension. It is 140- fold selective for A2A vs A1 receptors [27], and does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, thus it is of great utility in cardiovascular studies. CGS 21680 is also highly selective for the A2A vs A2B receptor [28], although its affinity at A3 receptors is greater than its A2A receptor affinity. Tritiated CGS 21680 is a useful high affinity agonist radioligand for the A2A receptor displaying low non-specific membrane binding.

APEC is an ethylenediamine derivative of CGS 21680 which is even more potent at the A2A subtype and is also moderately selective for this subtype. APEC is an amine-functionalized congener (see ADAC above), which does readily cross the blood-brain barrier [29]. Thus, administered peripherally it is suitable for the study of the function of A2A receptors in the central nervous system. The covalent conjugate of APEC with p-aminophenylacetic acid (PAPA-APEC) is useful as a high affinity radioligand for A2A receptors and was used for photoaffinity crosslinking in the first study to distinguish A1 and A2A receptors as distinct molecular species [30]. APEC has been used as a chemical precursor for a fluorescent probe of the A2A receptor [31], and its conjugation with a bifunctional crosslinking reagent has resulted in an irreversibly acting A2A agonist with coronary vasodilator properties.

HENECA (adenosine 2-(hexynyl)-5′-ethyluronamide), which is modified with an alkyne group at the 2-position as well as at the 5′-position, is a highly potent vasodilator and A2A receptor agonist with a Ki of 2.2 nM in binding assays [32], although it is not as selective as CGS 21680 for the A2A vs. the A1 and A3 receptors.

A2A Receptor Antagonists

Among highly potent and selective non-xanthine antagonists for the A2A subtype are ZM241385 (4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[l,2,4]triazolo[2,3a][l,3,5] triazinyl-amino]ethyl)-phenol) [33] and SCH 58261. SCH 58261 (5-amino-7-(2-phenylethyl)-2-(2-furyl)pyrazolo[4,3-e]-l,2,4-triazolo[l,5-c]pyrimidine) [34] is highly selective for A2A vs. both A1 and A2B receptors and has been tritiated for use as a radioligand [35]. ZM241385 is the most potent of A2A antagonists yet reported. Its selectivity vs A2B receptors is not as high as the corresponding selectivity of SCH 58261. In fact, tritiated ZM241385, while a superb radioligand at A2A receptors, is of sufficiently high affinity at recombinant A2B receptors for use as a radioligand when these receptors are expressed in systems lacking A2A receptors [21].

Although most 8-substituted alkylxanthine derivatives reported are selective for the A1 subtype, 8-styrylxanthines have been demonstrated to be A2A selective antagonists. KF 17837 (7-methyl-(8-(3,4-dimethyloxystyryl)-l,3-dipropyl-xanthine) is such a styrylxanthine having roughly 100-fold A2A receptor selectivity that was introduced by the Kyowa Hakko Co [36]. KF 17837 and related A2A-antagonists such as the 1,3-diethyl homologue, KW 6002 have entered clinical trials as potential novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease. CSC (8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine) displays selectivity for A2A vs A1 and A2B receptors of 520-fold and 62-fold, respectively [8].

A3 Receptor Agonists

The first highly potent and selective A3 agonists contain substitution at both 5′- and N6-positions. One of the most widely used A3 receptor agonists is N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluron-amide (IB-MECA) which is 50-fold selective [37] for A3 vs either A1 or A2A receptors in vitro and appears to be highly A3 selective in vivo [38, 39].

The corresponding derivative which also contains a 4-amino group in the benzyl ring is I-AB-MECA, which is used widely as a high affinity radioligand for recombinant A3 receptors [40], although in autoradiographic studies of rat brain sections it was found to label also A1 and A2A receptors.

The 3-chlorobenzyl derivative of NECA (MRS 452) has been demonstrated to be cardioprotective via the selective activation of A3 receptors.

Substitution of adenosine analogues at the 2-position in combination with modifications at N6 and 5′-positions was found to further enhance A3 selectivity [41]. Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide) displayed a Ki value of 0.33 nM at A3 receptors and is selective for A3 vs A1 and A2A receptors by 2500- and 1400-fold, respectively. A3 agonists have been shown to both inhibit adenylyl cyclase and activate phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-specifıc phospholipase C, with a rank order of potency that reflects the order of affinity determined in binding assays but at generally higher concentrations than the Ki values in competition of binding [41, 42], A3 receptor activation has also been shown to be coupled to activation of phospholipase D [43]. There may be differences in the relative activation of various second messenger systems based on the concentration of the A3 agonists. Low concentrations of A3 agonists such as Cl-IB-MECA (<100 nM, Fig. 1) have been shown to antagonize the A1 receptor mediated inhibition of EPSPs in hippocampal slices [44], High concentrations of A3 agonists have been found to induce apoptosis [45], thus intense activation of the A3 receptor may have a damage-inducing, rather than a protective role.

In human ADF cells of astroglial lineage, 100 nM Cl-IB-MECA caused a marked reorganization of the cytoskeleton, with appearance of stress fibers and numerous cell protrusions (which became enriched in the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL), accompanied by induction of the expression of Rho, a small GTP-binding protein [46]. A high concentration of Cl-IB-MECA (≥ 10 μM) was lethal to cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons, and the toxic effects of glutamate were also augmented.

A3 receptors are present in relatively high density in human peripheral blood eosinophils. Cl-IB-MECA was found to be very potent in inhibition of eosinophil migration without affecting adhesion receptors CD18 and selectin or assembly of F-actin [47].

MDL 201,449A is a carbocyclic adenosine derivative that acts as a weak, selective A3 agonist [48].

A3 Receptor Antagonists

Since xanthines tended to bind only weakly to A3 receptors, an alternate strategy, i.e. screening diverse molecules in chemical libraries for leads, was adopted in the design of selective A3 receptor antagonists. The Merck group [49], using high throughput screening of heterocyclic compounds, has identified antagonists which are highly selective for human A3 receptors.

1,4-Dihydropyridines, known as potent blockers of L-type calcium channels and used widely in treating coronary heart disease, were found to bind appreciably to human adenosine A3 receptors [42]. Common dihydropyridine drugs typically bound either non-selectively (for example, nifedipine, with a Ki value of 8.3 μM) or in some cases with selectivity for the A3 vs other adenosine receptor subtypes (for example, S-niguldipine, with a Ki value of 2.8 μM).

1,4-Dihydropyridines have been used as a template, in which it has been possible to select for affinity at adenosine receptors and completely deselect for affinity at L-type Ca2+-channels. Such a compound is MRS 1191 (3-ethyl 5-benzyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydro-pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate), which has been found to inhibit radioligand binding at the human A3 receptor with a Ki value of 31 nM, while the same derivative was nearly inactive in binding at A1 and A2A receptor sites (i.e. >1300-fold selective). MRS1191 is moderately selective at rat A3 receptors, with a Ki value of 1.42 μM. It competitively antagonized the effects of N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine (IB-MECA,), an A3 receptor selective agonist, on inhibition of adenylyl cyclase mediated by the recombinant human A3 receptor. Dihydropyridine antagonists of A3 receptors have also proven selective in chick cardiac myocytes, in which the activation of A3 receptors induces protective anti- ischemic effects. MRS 1191 was also shown to be A3 receptor-selective in the rat hippocampus, in which it was demonstrated that A3 receptor activation suppresses the effects of activation of presynaptic A1 receptors on inhibition of neurotransmitter release [44], MRS 1191 was also utilized to demonstrate that presynaptic A3 receptor activation antagonizes group III metabotropic glutamate autoreceptors [50].

Antagonism at human A3 receptors by MRS 1191 was demonstrated in functional assays consisting of agonist-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase and the stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S to the associated G-proteins, with a KB value of 92 nM [42].

A pyridine derivative, MRS 1523 (5-ethyl 2-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-4-propyl-6- phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate) is highly potent at human A3 receptors [51]. It is one of the few A3 antagonists reported to be selective and potent at both human and rat A3 receptors, with Ki values of 18.9 and 113 nM, respectively.

MRS 1220 is an N5-p-phenylacetyl derivative of the non-selective non-xanthine antagonist CGS 15943 (9-chloro-2-(2-furyl)[l,2,4]triazolo[l,5-c]quinazolin-5-amine). While MRS 1523 is an A3 antagonist of broad application to various species, the triazoloquinazoline MRS 1220, is extremely potent in binding to the human (Ki 0.65 nM) but not the rat A3 receptor [42].

Recently, a series of isoquinoline derivatives such as VUF8504 were reported to be antagonists selective for human A3 receptors [52].

III. TYPES OF ANTI-ISCHEMIC CARDIOPROTECTION

Adenosine-mediated cardioprotection can be separated into two types. The first type of cardioprotection is an acute effect in which the presence of adenosine during an episode of ischemia can protect the cardiac myocyte against the deleterious effect of ischemia. The second type of adenosine-mediated cardioprotection is ischemic preconditioning in which adenosine can produce a protective effect with a “memory” that confers ischemia resistance on the cardiac myocyte long after adenosine or adenosine agonist has been removed.

A. Acute Cardioprotective Effect of Adenosine

In this type of cardioprotection, activation of adenosine receptor during acute ischemia can produce a potent anti-ischemic effect. The advantage of this type of cardioprotection is that activation of adenosine receptor in the ischemic cardiac myocyte can delay or prevent myocyte death and thus produce a beneficial effect even after ischemia has begun. Recent studies show that either A1 or A3 receptor can mediate such an acute cardioprotective effect [19]. It is not unexpected that the first identified and the most well- characterized adenosine receptor in the myocardium, the adenosine A1 receptor, is capable of mediating such protection. However, the finding that activation of the adenosine A3 receptor can exert an acute cardioprotective effect during ischemia is novel and suggests that the adenosine A3 receptor is also an important mediator of the protective action of adenosine in the heart.

B. Adenosine and Ischemic Preconditioning

The original observations of ischaemic preconditioning were made in animals. As described before, Murry et al. [53] observed that repetitive short periods of ischaemia rendered the myocardium of dogs less susceptible to a subsequent prolonged and otherwise lethal episode of ischaemia. This seminal observation provoked studies proving that ischaemic preconditioning can limit infarct size in dogs [54–56], pigs [57], rabbits [58, 59], and rats [60].

Evidence for such protective preconditioning also exists in humans (61–63). Adenosine plays a key role in triggering and mediating the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning in most animal species including humans [53, 64–66, 61, 54, 67, 62, 68–71, 63, 72], Studies of adult human and rabbit ventricular myocytes and cultured neonatal rat and embryonic chick cardiac myocytes provided important insights by indicating that the cardioprotective mechanism of preconditioning is exerted, at least in part, at the level of and by the cardiac myocytes in the intact heart [73–75].

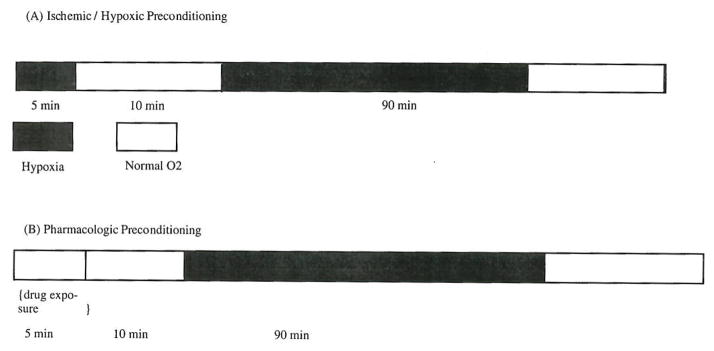

Using a cardiac myocyte model of simulated ischemia and ischemic preconditioning (Fig. 3), Liang et al [3] provided the first direct evidence that the cardiac myocyte expresses functional adenosine A3 receptors and that the A3 receptor can mediate the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning. Thus, in addition to the A1 receptor, the A3 receptor is also capable of mediating preconditioning. These data raised the question of why cardiac myocytes have two adenosine receptor subtypes that appear to mediate similar cardioprotective functions. The most recent evidence suggests that, on the contrary, the adenosine A3 receptor serves a different cardioprotective function as compared to the A1 receptor [14]. While activation of both A1 and A3 receptors can mimic the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning, the A3 receptor can mediate a more sustained cardioprotective effect, as manifested by a more prolonged duration of its preconditioning-mimicking effect.

Fig. 3.

Preconditioning Protocol. The protocol has been used in most of the experimental studies on ischemic preconditioning. The preconditioning studies carried out in patients undergoing PTCA also employed a similar protocol.

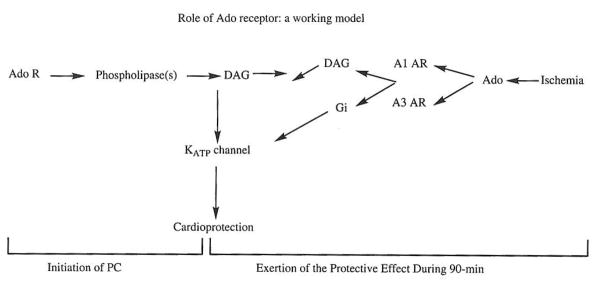

IV. SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION MECHANISM LEADING FROM ADENOSINE RECEPTOR ACTIVATION TO CARDIOPROTECTION: A WORKING MODEL

To facilitate the determination of the signalling mechanism(s) underlying the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning, the process of preconditioning can be divided into two phases (Fig. 4). The first phase is the trigger or initiation, which occurs during the first episode of ischemia that is brief in duration. The second phase is the actual exertion of protection during the subsequent, second episode of ischemia that is prolonged and that is responsible for the injury to the cardiac myocyte. The second phase is also known as the maintenance phase of ischemic preconditioning. The release of adenosine and the subsequent activation of adenosine receptors are responsible for both initiating and exerting the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning. Although much more work is needed, accumulating evidence is emerging to support a role of phospholipase C or D, protein kinase C, and ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP channel) in either the initiation and/or the maintenance phase of the ischemic preconditioning. The exact sequence of signalling events and the relationship between these post-receptor signalling molecules during both phases of preconditioning remain to be elucidated. Investigation of these signalling mechanisms should lead to the identification of new potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of patients with ischemic heart disease.

Fig. 4.

A working model for the sequence of signaling events leading to the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning. In this model, the preconditioning process is divided into two phases, the initiation phase during which the process is triggered, and the maintenance phase during which the actual cardioprotection is exerted. The roles of adenosine receptor, phospholipases, diacylglycerol, protein kinase C and KATP channel are proposed.

V. POTENTIAL CLINICAL USEFULNESS OF ADENOSINE ANALOGS

A. Clinical Evidence for Ischemic Preconditioning: Patient-oriented Investigations

1. In vitro Study on Human Cardiac Myocyte

Studies that provided the most direct evidence that preconditioning exists in humans ranged from in vitro experiments performed in cultured human cardiac ventricular myocytes [74] to various in vivo investigations in patients with known ischemic heart disease. In the in vitro study, human ventricular myocytes subjected to brief periods of ischaemia before 90 minutes of sustained ischaemia showed improved survival, compared to myocytes exposed to the 90-minute sustained ischaemia alone.

2. Investigation in patients undergoing CABG

An example of clinical investigation which has implications for clinical practice, a study published in the Lancet in 1993 [76] described a preconditioning protocol in 14 patients undergoing cardio-pulmonary bypass. In this clinical protocol for preconditioning, 7 patients were subjected to two 3-minute periods of cross-clamping interspersed with 2 minutes of reperfusion before they were subjected to 10 minutes of cross-clamping for distal aorto-coronary anastomoses during coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The patients who received the two 3-minute periods of initial cross-clamping before the subsequent 10-minute cross clamping had significantly higher levels of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – as assessed by analysis of myocardial biopsy specimens – than those who were subjected to the 10-minute cross-clamping alone.

3. Studies on Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction

That ischaemic preconditioning might play an important role in humans became even more apparent after an interesting series of retrospective observations was made with regard to the effect of preinfarct angina on the outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI). In a study of 153 patients with their first Q-wave anterior wall acute MI, 100 had angina while 53 had no antecedent symptoms [77], The presence of angina before acute MI was associated with a lower incidence of sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, cardiac rupture, lower in-hospital mortality, as well as lower peak creatine kinase (CK) than in patients without antecedent angina. No significant difference in collateral circulation was found between the two groups.

In the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 4 trial [78], 218 patients with acute MI and history of any prior angina experienced less in-hospital death, severe congestive heart failure (CHF) or shock than 198 patients with acute MI without prior angina. In addition, patients with any history of angina had smaller CK elevations and were less likely to develop Q-waves on their electrocardiograms (ECGs). Interestingly, this effect was again not dependent on angiographically detectable coronary collaterals, suggesting that the benefit of pre-infarct angina was indeed due to ischaemic preconditioning.

A similar study on 25 patients with their first anterior MI treated with thrombolysis [79] confirmed that patients with new-onset prodromal angina showed significantly lower CK-MB elevations and eventually suffered smaller infarcts (as assessed by the size of hypokinesis) than patients without prodromal angina. Again, no evidence of increased collateral circulation in patients with prodromal angina was found, further supporting the hypothesis of ischaemic preconditioning being directly responsible for the beneficial effect seen. The later TIMI 9 study [80] demonstrated a critical time dependency for the beneficial effect of pre-infarct angina. During a 30-day follow-up after MI, patients who had angina less than 24 hours before MI had lower mortality, less CHF, and a lower incidence of shock or recurrent MI than patients without angina or with angina more than 48 hours before MI or never had angina before. This observation correlated well with the previous studies on animals showing a clear time-limit (window) for ischaemic preconditioning.

4. Ischemic Preconditioning and Patients Undergoing PTCA

In parallel to the retrospective studies showing the effect of angina on the outcome of subsequent MI, several prospective studies demonstrated the importance of ischaemic preconditioning in humans and the possibilities for future therapeutic interventions. Initial studies involved intracoronary balloon inflations, which were used to elicit the cardioprotective effect. In one of the earliest studies, repeated coronary artery occlusions during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) were performed [61]. It was observed that during the second of two periods of occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, patients experienced less anginal discomfort, and there was less ST segment shift, lower mean pulmonary artery pressure and less lactate production.

A subsequent study [62] demonstrated that during five successive balloon inflations within the LAD, there was a reduction of angina, ST-segment deviation, left ventricular (LV) filling pressure and impairment of LV ejection fraction. This study differed from previous ones by also demonstrating enhancement of recruitable collateral circulation in 10 of 17 patients during successive balloon inflations.

Recent research has introduced the concept of “pharmacological preconditioning” with the use of substances, e.g., adenosine, called “preconditioning mimetics” – to achieve the same cardioprotective effect but without the hazards of temporary coronary occlusion. The concept of preconditioning mimetics is based on the rationale that activation of adenosine receptor by the adenosine released during myocardial ischemia is responsible for initiating the preconditioning elicited during the first balloon inflation. Thus, one can mimic the salutary effect of the balloon inflation- induced preconditioning by giving an adenosine receptor agonist directly before any balloon inflation.

The success of such preconditioning mimetics was demonstrated in a study in which 15 patients received a 10-minute intracoronary infusion of adenosine [81] before the first PTCA balloon inflation. In patients who received adenosine, the subsequent 3 consecutive intracoronary balloon inflations produced smaller ST-segment shifts, compared to control patients who received only normal saline prior to PTCA. In addition, in control patients, the ST-segment shift in the intracoronary ECG was significantly greater during the first inflation than during the second and third inflations, consistent with ischaemic preconditioning. On the other hand, in the adenosine-treated patients, there was no differences in the ST-segment shifts during the three inflations. Even more importantly, the reduction in the ST-segment shift afforded by adenosine was greater than that afforded by ischaemic preconditioning.

Since protective effect of adenosine is a receptor-mediated phenomenon, it can be blocked by adenosine receptor antagonists (e.g., bamiphylline, aminophylline). In one study [82], bamiphylline - a selective antagonist of A1 adenosine receptors - abolished the effect of adenosine on ST-segment shifts during PTCA. In another study [83], aminophylline, a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, inhibited ischaemic preconditioning – as assessed by analysis of the intracoronary ST-segment changes during angioplasty.

B. Ischaemic Preconditioning: Bridging Basic Research and Clinical Practice

Studies on ischaemic preconditioning have followed an established pattern of scientific discoveries; original observations made in a living organism are followed by in vitro studies attempting to elucidate the mechanisms of the observed phenomena. Once the mechanism is known, or at least a plausible hypothesis is postulated, clinical tests and trials follow, eventually bringing a new modality of medical treatment.

Although adenosine was used to successfully induce a preconditioning-like effect, there are a number of limitations which restrict the utility in a number of situations. Because of the extraordinary short life of adenosine (<10 seconds), adenosine needs to be administered as a continuous infusion in order to ensure a consistent occupancy and activation of the adenosine receptor. Adenosine can activate all four adenosine receptors; activation of the A2A receptor can be potentially deleterious and counteract the myocyte protective effect mediated by A1 or A3 receptor. Activation of the A1 receptor by adenosine may produce bradycardia or atrioventricular conduction block, especially if it is administered in the right coronary artery or the left-dominant circumflex artery. Adenosine itself is not orally available and can only be administered as an intravenous or intracoronary drug. Its availability to the cardiac adenosine receptor is limited by the extremely effective uptake system in the circulating blood cells and the endothelium. In this context, receptor-selective agents should prove to be superior to adenosine itself.

C. Potential Clinical Conditions Under which Pharmacological Preconditioning Agents May be Beneficial

unstable or stable angina – where administration of preconditioning mimetics could potentially reduce future infarct size or perhaps even prevent infarction altogether,

acute MI / reperfusion – on-going studies (e.g. HALT-MI) are examining the hypothesis that pharmacological preconditioning with adenosine receptor agonists could prevent/decrease the size of MI and extent of reperfusion injury,

PTCA – where the use of preconditioning mimetics could decrease/prevent CK leak, decrease potential myocardial injury and ultimately improve outcomes,

heart surgery (traditional CABG or “minimally invasive” procedures, like MIDCAB) – where preconditioning mimetics could minimize the ischaemic insult to the myocardium,

heart transplantation – where preconditioning mimetics could protect the donor heart peri-operatively, improve its future functioning and perhaps reduce the incidence of coronary artery disease in the transplanted heart.

The results of the above mentioned retrospective and prospective clinical observations on myocardial preconditioning (whether ischaemic or pharmacological) provide the initial encouraging clues to treat patients with ischemic heart disease. More studies in patients with ischemic heart disease are required before preconditioning can be applied routinely in clinical practice. Of particular interest would be tests on pharmacological preconditioning involving various preconditioning mimetics, like the already mentioned adenosine, KATP channel openers and/or other mediators postulated to be involved in the molecular mechanism of preconditioning. These agents could prove safer and easier to administer than intracoronary balloon inflations (ischaemic preconditioning). More importantly, these potentially novel pharmacologically preconditioning agents can be administered under clinical conditions in which balloon inflation is not part of the therapeutic procedure. Potential clinical situations during which these agents may be beneficial are discussed below.

References

- 1.Linden J, Jacobson KA. In: Cardiovascular Biology of Purines. Burnstock Geoffrey, Dobson James G, Liang Bruce T, Linden Joel., editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 1998. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiles GL. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathern GP, Headrick JP, Liang BT. In: Cardiovascular Biology of Purines. Burnstock Geoffrey, Dobson James G, Liang Bruce T, Linden Joel., editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 1998. pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang BT. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 1992;2:100. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(92)90014-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons M, Musikabhumma P, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. Circ (suppl) 1998;98:2196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein B, Kiehn J, Neumann J. In: Cardiovascular Biology of Purines. Burnstock Geoffrey, Dobson James G, Liang Bruce T, Linden Joel., editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht/Boston/London: 1998. pp. 108–125. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auchampach JA, Jin X, Wan TC, Caughey GH, Linden J. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:846. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson KA, von Lubitz DKJE, Daly JW, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptor ligands: differences with acute chronic treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:108. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fozard JR, Pfannkuche HJ, Schuurman HJ. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;298:293. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00822-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwabe U, Trost T. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1980;313:179. doi: 10.1007/BF00505731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracey WR, Magee W, Masamune H, Kennedy SP, Knight DR, Buchholz RA, Hill RJ. Cardiovascular Research. 1997;33:410. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Pliysiol Reviews. 1990;70:761. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klotz KN, Lohse MJ, Schwabe U, Cristalli G, Vittori S. Grifantini M2-Chloro-N6-[3H]cyclopentyladenosine ([3H]CCPA)--a high affinity agonist radioligand for A1 adenosine receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1989;340:679. doi: 10.1007/BF00717744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang BT, Jacobson KA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Lubitz DKJE, Paul IA, Carter M, Jacobson KA. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249:265. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90521-i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snowdy S, Liang HX, Blackburn B, Lum R, Nelson M, Wang L, Pfister J, Sharma BP, Wolff A, Belardinelli L. Brit J Pharmacol. 1999;126:137. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson KA, Ukena D, Padgett W, Kirk KL, Daly JW. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:1697. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Belardinelli L, Jacobson KA, Otero DH, Baker SP. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:491. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stambaugh K, Jiang J-L, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Lubitz DKJE, Lin R-C, Bischofberger N, Beenhakker M, Boyd M, Lipartowska R, Jacobson KA. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999b;369:313. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji XD, Jacobson KA. Drug Design Discovery. 1999;16:89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guay-Broder C, Jacobson KA, Barnoy S, Cabantchik I, Guggino WB, Zeitlin PL, Turner RJ, Vergara L, Eidelman O, Pollard HB. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9079. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfister JR, Belardinelli L, Lee G, Lum RT, Milner P, Stanley WC, Linden J, Baker SP, Schreiner G. J Med Chem. 1997;40:1773. doi: 10.1021/jm970013w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin PL, Wysocki RJ, Barrett RJ, May JM, Linden J. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji X-D, Stiles GL, van Galen PJM, Jacobson KAJ. Receptor Res. 1992;12:149. doi: 10.3109/10799899209074789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchison AJ, Webb RL, Oei HH, Ghai GR, Zimmerman MB, Williams M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hide I, Padgett WL, Jacobson KA, Daly JW. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikodijevic O, Daly JW, Jacobson KA. FEBS Letters. 1990;261:67. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Hutchison AJ, Williams M, Stiles GL. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe RT, Skolnick P, Jacobson KA. J Fluoresc. 1992;2:217. doi: 10.1007/BF00865279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cristalli G, Camaioni E, Vittori S, Volpini R, Borea PA, Conti A, Dionisotti S, Ongini E, Monopoli A. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1462. doi: 10.1021/jm00009a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zocchi C, Ongini E, Conti A, Monopoli A, Negretti A, Baraldi PG, Dionisotti S. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poucher SM, Keddie JR, Singh P, Stoggall SM, Caulkett PWR, Jones G, Collis MG. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dionisotti S, Ferrara S, Molta C, Zocchi C, Ongini E. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada J, Suzuki F, Nonaka H, Ishii A, Ichikawa S. J Med Chem. 1992;35:2342–2345. doi: 10.1021/jm00090a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallo-Rodriguez C, Ji X-D, Melman N, Siegman BD, Sanders LH, Orlina J, Fischer B, Pu Q-L, Olah ME, van Galen PJM, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 1994:37. doi: 10.1021/jm00031a014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson KA. TIPS. 1998;19:184. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Lubitz DKJE, Lin R-C, Boyd M, Bischofberger N, Jacobson KA. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999a;367:157. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:978. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim HO, Ji XD, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3614. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson KA, Park KS, Jiang J-l, Kim Y-C, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Ji XD. Pharmacological characterization of novel A3 adenosine receptor-selective antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1157. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali H, Choi OH, Fraundorfer PF, Yamada K, Gonzaga HMS, Beaven M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunwiddie TV, Diao L, Kim HO, Jiang J-L, Jacobson KA. J Neurosci. 1997;17:607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohno Y, Sei Y, Koshiba M, Kim HO, Jacobson KA. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;221:849. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbracchio MP, Rainaldi G, Giammarioli AM, Ceruti S, Brambilla R, Cattabeni F, Barbieri D, Franceschi C, Jacobson KA, Malorni W. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997:241. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker BA, Jacobson MA, Knight DA, Salvatore CA, Weir T, Ahou D, Bai TR. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:531. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowlin TL, Borcherding DR, Edwards CK, McWhinney CD. Cell and Mol Biol. 1997;43:345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson M, Chakravarty PK, Johnson RG, Norton R. Drug Devel Res. 1996;37:131. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macek TA, Schaffhauser H, Conn PJ. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li A-H, Moro S, Melman N, Ji X-d, Jacobson KA. J Med Chem. 1998;41:3186. doi: 10.1021/jm980093j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Muijlwijk-Koezen JE, Timmerman H, Link R, Van der Goot H, Jzerman IAP. J Med Chem. 1998;41:3994. doi: 10.1021/jm980037i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Circulation. 1986;75:1124. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li G, Vasquez J, Gallagher K, Lucchesi B. Circulation. 1990;82:609. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nao B, McClanahan T, Groh M, Schott R, Gallagher K. Circulation. 1990;82(Suppl [3]):III–271. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitakaze M, Hori M, Takashima S, Sato H, Kamada T. Circulation. 1991;84(Suppl [2]):11–306. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2135. [abst] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schott RJ, Rohmann S, Braun ER, Schaper W. Circ Res. 1990;66:1133. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwamoto T, Miura T, Adachi T, et al. Circulation. 1991;83:1015. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thornton J, Stripkin S, Liu GS, et al. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1822. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.6.H1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y, Kloner R. Circulation. 1991;84(Suppl [2]):II–619. [abst] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deutsch E, Berger M, Kussmaul WG, Hirshfield JW, Herrmann HC, Laskey WK. Circ. 1990;82:2044. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cribier AL, Korsatz R, Koning P, Rath H, Gamra H, Stix G, Merchant S, Chan C, Letac B. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:578. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90011-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomai F, Crea F, Gaspardone A, Versaci F, DePaulis R, Polisca P, Chiariello L, Gioffre PA. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:846. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olafsson B, Forman MB, Puett DW, Pou A, Cates CU. Circ. 1987;76:1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Babbitt DG, Virmani R, Forman MB. Circ. 1989;80:1388. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyatt D, Ely SW, Lasley RD, Walsh R, Mainwaring R, Berne RM, Mentzer RM. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Auchampach JA, Grover GJ, Gross GJ. Cardiovas Res. 1992;26:1054. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Downey JM. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1992;2:170. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(92)90045-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ely SW, Berne RM. Circulation. 1992;85:893. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miura T, Ogawa T, Iwamoto T, Shimamoto K, Iimura O. Circ. 1992;86:979. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulz R, Rose J, Heusch G. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1341. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yao Z, Gross GJ. Circ. 1994;89:1229. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Armstrong S, Ganote CE. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1049. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.7.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ikonomidis JS, Tumiati LC, Weisel RD, Mickle DAG, Li R-K. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1285. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Webster KA, Discher DJ, Bishopric NH. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:453. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yellon DM, Alkulaif AM, Pugsley WB. Lancet. 1993;342:276. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, Asakura Y, Abe S, Meguno T, Akaishi M, Mitamura H, Handa S, Ogawa S. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:755. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kloner RA, Shook T, Przyklenk K, Davis VG, Junio L, Matthews RV, Burstein S, Gibson M, Poole WK, Cannon CP, McCabe C, Braunwald E for TIMI Investigators. Circulation. 1995;91:37. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ottani F, Galvani M, Ferrini D, Sorbello F, Limonetti P, Pantoli D, Rusticali F. Circulation. 1995;91:291. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kloner RA, Shook T, Antman EM, Cannon CP, Przyklenk K, McCabe CH, Braunwald E TIMI 9 Investigators [abst] Circulation. 1996;94(Suppl [1]):I–611. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.11.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leesar MA, Stoddard M, Ahmed M, Broadbent J, Bolli R. Circulation. 1997;95:2500. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.11.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tomai F, Crea F, Caspardone A, Versaci F, DePaulis R, Penta de Peppo A, Chiariello L, Gioffre’ PA. Circulation. 1994;90:700. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Claeys MJ, Vrints CJ, Bosmans JM, Concraads VM, Snoeck JP. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:539. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]