Abstract

Cbl-associated protein (CAP) localizes to focal adhesions and associates with numerous cytoskeletal proteins; however, its physiological roles remain unknown. Here, we demonstrate that Drosophila CAP regulates the organization of two actin-rich structures in Drosophila: muscle attachment sites (MASs), which connect somatic muscles to the body wall; and scolopale cells, which form an integral component of the fly chordotonal organs and mediate mechanosensation. Drosophila CAP mutants exhibit aberrant junctional invaginations and perturbation of the cytoskeletal organization at the MAS. CAP depletion also results in collapse of scolopale cells within chordotonal organs, leading to deficits in larval vibration sensation and adult hearing. We investigate the roles of different CAP protein domains in its recruitment to, and function at, various muscle subcellular compartments. Depletion of the CAP-interacting protein Vinculin results in a marked reduction in CAP levels at MASs, and vinculin mutants partially phenocopy Drosophila CAP mutants. These results show that CAP regulates junctional membrane and cytoskeletal organization at the membrane-cytoskeletal interface of stretch-sensitive structures, and they implicate integrin signaling through a CAP/Vinculin protein complex in stretch-sensitive organ assembly and function.

Keywords: CAP, Integrin, Vinculin, Muscle attachment site, Chordotonal organ, Drosophila

INTRODUCTION

Interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) are crucial for many biological processes. These include cell migration, directed process outgrowth, basement membrane-mediated support of tissues and maintenance of cell shape (Bökel and Brown, 2002; Hogg et al., 2011; Nakamoto et al., 2004; Watt and Fujiwara, 2011). Communication between cells and ECM proteins often occurs through the action of α/β-integrin heterodimers, a receptor complex that forms adhesive contacts, including focal adhesions, hemiadherens junctions, costameres and myotendinous junctions (Bökel and Brown, 2002). In response to extracellular forces, focal adhesions undergo structural changes and initiate signaling events that allow adaptation to tensile stress (Geiger et al., 2009). Vinculin is thought to be the primary force sensor in the integrin complex, mediating homeostatic adaptation to external forces (Carisey and Ballestrem, 2011; Grashoff et al., 2010; Hytönen and Vogel, 2008).

Vinculin-binding partners include proteins belonging to the CAP (Cbl-associated protein) protein family (Kioka et al., 1999). However, the physiological significance of this association is unknown. Mammalian CAP proteins are components of focal adhesions in cell culture (Kioka et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2006). In myocytes, CAP localizes to integrin-containing complexes called costameres that anchor sarcomeres to muscle cell membranes (Zhang et al., 2007). There are three mammalian CAP protein family members: CAP, Vinexin and ArgBP2 (Kioka et al., 2002). CAP associates in vitro with many proteins, including the cytoskeletal regulators Paxillin, Afadin and Filamin, vesicle trafficking regulators such as Dynamin and Cbl, and the lipid raft protein Flotillin (Chiang et al., 2001; Mandai et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007). In vitro studies demonstrate that CAP regulates the reassembly of focal adhesions following nocodazole dissolution (Zhang et al., 2006). However, despite extensive studies on CAP (Kioka, 2002; Zhang et al., 2006), little is known about its functions in vivo. Cap (Sorbs1) mutant mice are defective in fat metabolism, and targeted deletion of the vinexin gene results in wound-healing defects (Kioka et al., 2010; Lesniewski et al., 2007). Drosophila CAP binds to axin and is implicated in glucose metabolism (Yamazaki and Nusse, 2002; Yamazaki and Yanagawa, 2003). Analysis of CAP function in mammals is complicated by potential functional redundancy of the three related CAP proteins. Therefore, we have examined the function of Drosophila CAP, the single CAP family member in Drosophila, in vivo.

The Drosophila muscle attachment site (MAS) is an excellent system for studying integrin signaling. Somatic muscles in each segment of the fly embryo and larva are connected to the body wall through integrin-mediated hemiadherens junctions (Brown, 2000). Somatic muscles in flies lacking integrins lose their connection to the body wall (Brown et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2002; Clark et al., 2003; Zervas et al., 2001). Surprisingly, flies lacking Vinculin, a major component of cytosolic integrin signaling complexes, are viable and show no muscle defects (Alatortsev et al., 1997). Thus, unlike its mammalian counterpart, Drosophila Vinculin is apparently dispensable for the initial assembly of integrin-mediated adhesion complexes at somatic MASs.

The fly MAS is structurally analogous to the fly chordotonal organ. These organs transduce sensations from various stimuli, including vibration, sound, gravity, airflow and body wall movements (Caldwell and Eberl, 2002; Kamikouchi et al., 2009; Kernan, 2007; Yack, 2004; Yorozu et al., 2009). The chordotonal organ is composed of individual subunits called scolopidia, each containing six cell types: neuron, scolopale, cap, ligament, cap attachment and ligament attachment cells (Todi et al., 2004). Chordotonal neurons are monodendritic, and their dendrites are located in the scolopale space, a lymph-filled extracellular space completely enveloped by the scolopale cell (Todi et al., 2004). Within the scolopale cell, a cage composed of actin bars, called scolopale rods, facilitates scolopale cell envelopment of the scolopale space (Carlson et al., 1997; Todi et al., 2004). Thus, like the MAS, the actin cytoskeleton plays a specialized role in defining chordotonal organ morphology. Similarities between MASs and chordotonal organs include the requirement during development in both tendon and cap cells for the transcription factor Stripe (Inbal et al., 2004). Furthermore, both of these cell types maintain structural integrity under force and so are likely to share common molecular components dedicated to this function.

Here, we show that the Drosophila CAP protein is selectively localized to both muscle attachment sites and chordotonal organs. In Drosophila CAP mutants we observe morphological defects that are indicative of actin disorganization in both larval MASs and the scolopale cells of Johnston's organ in the adult. The morphological defects in scolopale cells result in vibration sensation defects in larvae and hearing deficits in adults. We also find that, like its mammalian homologues, Drosophila CAP interacts with Vinculin both in vitro and in vivo. These results reveal novel CAP functions required for actin-mediated organization of cellular morphology, lending insight into how CAP mediates muscle and sensory organ development and function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila genetics

Drosophila CAP deletion mutants were generated by imprecise excision of the P-element CAPCA06924 inserted in the intron proximal to the SH3 domain-coding exons. We generated multiple excisions, two deleting the first two SH3 domain-coding exons. These deletions are dCAP49e and dCAP42b, and delete 2.9 kb (genomic region 2R:6,190,378-6,193,350) and 2.7 kb (genomic region 2R:6,190,378-6,193,141), respectively, downstream of the CAPCA06924 P-element. A precise excision we generated called CAP49a was used as wild-type control. CAPCA06924,mys1, rhea1, flotillin-2KG00210 and tensin mutant by1 were from the Bloomington Stock Center; zasp9 and zasp56 mutants were a gift from Frieder Schock (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). Cheerio and paxillin RNAi lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Research Center.

Drosophila CAP miRNA constructs target the sequences CAGCTATGTTGAGATTGTCAGT and TTCAATACGCTGACGCAAAATG in the CAP-E transcripts encoding the C-terminal CAP SH3 domains. These constructs were generated as described previously (Chen et al., 2007). The stem-loop backbone and surrounding sequences were unaltered, and the Drosophila Mir6.1 gene-targeting miRNA sequence was replaced with the 22 bp complementary to the CAP transcript. Two mRNA constructs targeting distinct CAP sequences were inserted in tandem into the pUAST vector and used to generate transgenic flies.

Drosophila CAP antibody

The Drosophila CAP short isoform (CAP-E), which encodes the three SH3 domains, was cloned into the pGEX4T-1 vector to generate a GST fusion protein. Purified GST-CAP-E was injected into rabbits for polyclonal antibody production. GST-CAP-E-bound Affigel beads were used to affinity-purify CAP-specific antibodies.

Immunostaining and microscopy

Drosophila embryos were processed for immunostaining as described previously (Patel, 1994). For most experiments, fixation used 4% paraformaldehyde. For examination of larval muscle attachment sites, fillet preparations of wandering third instar larvae were prepared in PBS, as described previously (Brent et al., 2009). For Johnston's organ staining, adult heads with the proboscis removed were fixed in 4% PFA for 90 minutes at 4°C. After three washes with PBS, heads were incubated in 12% sucrose overnight and subsequently frozen in OCT. Cross-sections (20 μm) were cut using a cryostat. The following antibodies were used: anti-βPS integrin at 1:100 (DSHB), 22C10 at 1:200 (DSHB), 21A6 at 1:200 (DSHB), rabbit anti-85e-tubulin at 1:20 [a gift from T. C. Kaufman (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA) and A. Salzberg (Rappaport Institute, Haifa, Israel)], rabbit anti-CAP at 1:1000 (our antibody), rabbit anti-Zasp at 1:1000 (a gift from F. Schock), rabbit anti-pinch at 1:500 (a gift from M. C. Beckerle, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), anti-thrombospondin at 1:400 (a gift from T. Volk, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel), mouse anti-tiggrin at 1:200 (a gift from L. Fessler, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Electron microscopy

Drosophila third instar larval fillets from dCAP49e mutants and controls were processed as described with minor variations (Ramachandran and Budnik, 2010). Larval fillets were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in cacodylate buffer at 4°C overnight, stained first with 2% osmium tetroxide at 4°C for 1 hour and then with 2% uranyl acetate for 30 minutes. Samples were dehydrated by incubating with increasing concentrations of ethanol and equilibrated in varying concentrations of propylene oxide and Epon resin. Larval fillets were pinned to embedding molds using insect pins and embedded in Epon resin. Horizontal ultrathin sections of the larval fillet were cut using an ultramicrotome. Sections were subsequently stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate; TEM was performed using a Hitachi H-7000 transmission electron microscope. Ultrastructural analysis of Johnston's organs was performed as described previously (Todi et al., 2005).

Immunopurification

For each immunopurification experiment, 1.5 g of Drosophila embryos and 100 μg of Drosophila CAP antibody were used. Immunopurification was performed as described previously (Bharadwaj et al., 2004). The protein bands specific to wild-type lysates were excised, pooled, subjected to trypsin digestion and used for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis (Johns Hopkins Medical School Mass Spectrometry facility).

Vibration sensation assay

The vibration sensation assay was performed as described previously (Swierczek et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011). Approximately 96-hour-old third instar larvae of the specified genotypes were selected using GFP-balancer chromosomes. Larvae were placed on an agar plate lying directly over a speaker that provides pulses of vibration stimuli. Larvae were subjected to eight 1000 Hz, 1 V 1-second pulses followed by a 30-second pulse. Using the Multi-Worm Tracker (MWT) and choreography software (Swierczek et al., 2011), the behavior of the entire larval population (n=~100) on the dish was simultaneously tracked and analyzed. The hunch response was assessed by measuring the average mean midline body length of the entire larval population before and after vibration stimuli.

Auditory nerve electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recording of sound-evoked potentials (SEPs) was performed as described previously (Eberl et al., 2000; Eberl and Kernan, 2011).

RESULTS

Drosophila CAP genomic organization and CAP mutant generation

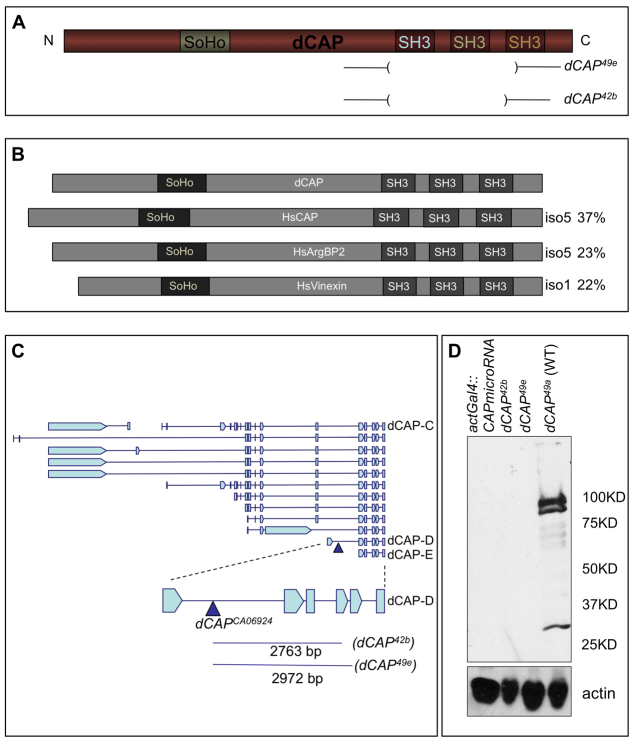

Drosophila CAP is the only member of the CAP gene family in Drosophila. Like its mammalian counterparts, Drosophila CAP possesses three C-terminal SH3 domains and an N-terminal SoHo (sorbin homology) domain (Fig. 1A). There are three mammalian CAP proteins: CAP, vinexin and ArgBP2. Drosophila CAP shows the highest amino acid sequence similarity to mammalian CAP (Fig. 1B) (Yamazaki and Nusse, 2002). Genomic DNA sequence, northern blot and western blot analyses reveal that there are multiple CAP isoforms in Drosophila, similar to mammalian CAPs (Fig. 1C) (Yamazaki and Nusse, 2002). The only coding region shared by all predicted Drosophila CAP protein isoforms is at the C terminus and encodes the SH3 domains. Through imprecise excision of a P transposable element (CAPCA06924), we generated two deletions, dCAP42b and dCAP49e, that remove the first two of the three conserved SH3 domains, and also a precise excision, dCAP49a, that serves as a control (Fig. 1A,C). Drosophila CAP mutants are viable and fertile. Western blot analysis of Drosophila embryonic and adult whole-body lysates using a CAP polyclonal antibody we raised against the Drosophila CAP C-terminal SH3 domains reveals multiple protein isoforms in wild-type flies that probably correspond to different Drosophila CAP isoforms; these bands are absent in dCAP42b and dCAP49e whole-body lysates (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Drosophila CAP protein domain organization, CAP genomic organization and generation of CAP loss-of-function mutants. (A) Domain organization of CAP protein domains, with CAP mutants shown below protein domain schematic. (B) Sequence alignment of CAP and its mammalian homologs. (C) Schematic of predicted CAP cDNA transcripts and CAP deletion mutants. The P-element CAPCA06924 (blue triangles) was used to generate two CAP deletion mutants: CAP42b and dCAP49e; the precise excision dCAP49a was used as a wild-type control. An enlarged image of isoform CAP-D is shown: blue lines indicate the extent of each deletion. (D) Whole-body lysates from adult flies of indicated genotypes were immunoblotted with anti-CAP (upper panel) and anti-actin (lower panel).

The imprecise CAP excision mutants dCAP49e and dCAP42b likely result in complete loss of CAP protein, but there remains the possibility that the N-terminal region of CAP might be generated in these mutants. Therefore, we also used a miRNA-mediated knock-down strategy to assess CAP loss-of-function (Chen et al., 2007). We generated transgenic fly lines harboring a construct containing two miRNAs, in tandem, that targeted two distinct C-terminal CAP sequences in the open reading frame, a region conserved in all predicted CAP miRNA products (Fig. 1C). Western blot analysis of adult whole fly body lysates from flies expressing the CAP tandem miRNAs under control of an actin-Gal4 driver did not detect any CAP protein (Fig. 1D). Functional miRNAs targeting any site in a mRNA result in degradation, or blockade of translation, of the entire mRNA (Du and Zamore, 2007); flies ubiquitously expressing these miRNAs probably lack all N-terminal CAP protein.

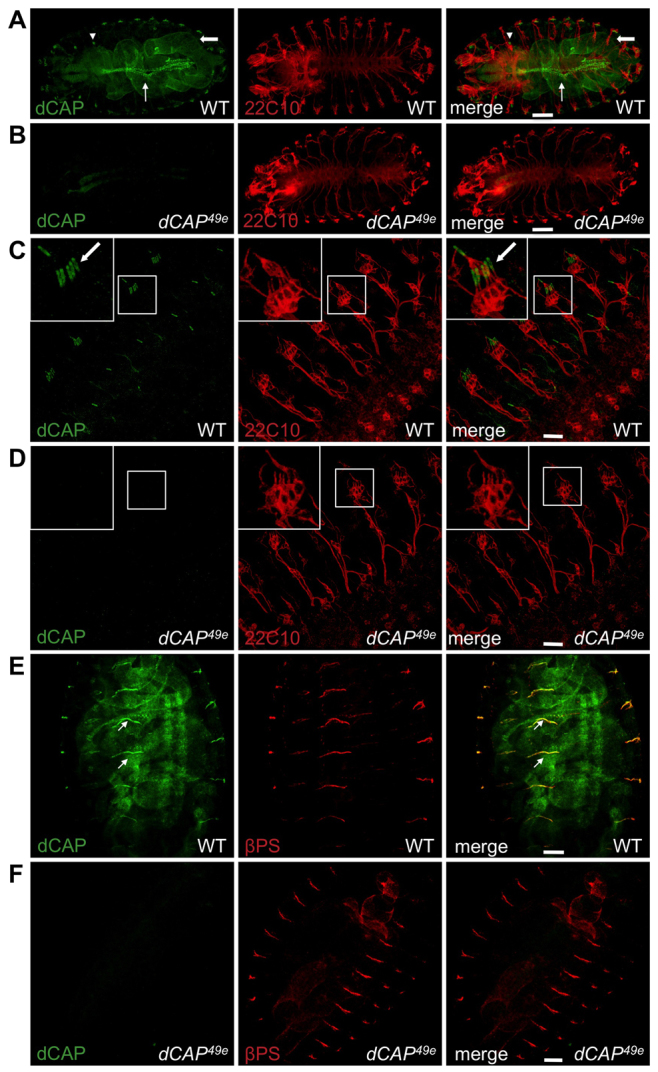

CAP localizes to muscle attachment sites and chordotonal organ scolopale cells

We next analyzed CAP protein expression throughout development using our CAP polyclonal antibody, which most probably recognizes all predicted Drosophila CAP isoforms. In stage 16 embryos, CAP is expressed predominantly in chordotonal sensory organs, somatic muscles, the dorsal vessel (the Drosophila heart) and the gut (Fig. 2A,C,E). CAP immunostaining is specific for endogenous CAP protein as dCAP49e mutants, which lack the genomic region encoding the CAP SH3 domains, exhibit no CAP protein (Fig. 2B,D,F). In somatic muscles, CAP colocalizes with the βPS integrin subunit at muscle attachment sites (MASs) (Fig. 2E). In third instar larvae, CAP protein expression persists at MASs and also at Z-lines of somatic muscles, although Z-line expression is lower in comparison with MAS expression (see below: Fig. 5A; supplementary material Fig. S1C).

Fig. 2.

Embryonic expression of CAP protein. (A-D) Wild-type (A,C) and dCAP49e (B,D) embryos stained with anti-CAP and 22C10 antibody (which labels all sensory neurons). (A,B) Wild-type embryos show CAP staining in chordotonal organs (arrowheads), dorsal vessels (thin arrows) and gut (thick arrows); this staining is absent in CAP mutants. (C,D) Higher magnification image of CAP localization in chordotonal organ scolopale cells (arrows) in wild type, but not dCAP49e,embryos. (E,F) Wild-type and dCAP49e embryos immunostained with anti-CAP and anti-βPS integrin; CAP colocalizes with βPS integrin at MASs (arrows). Scale bars: 60 μm in A,B; 20 μm in C-F.

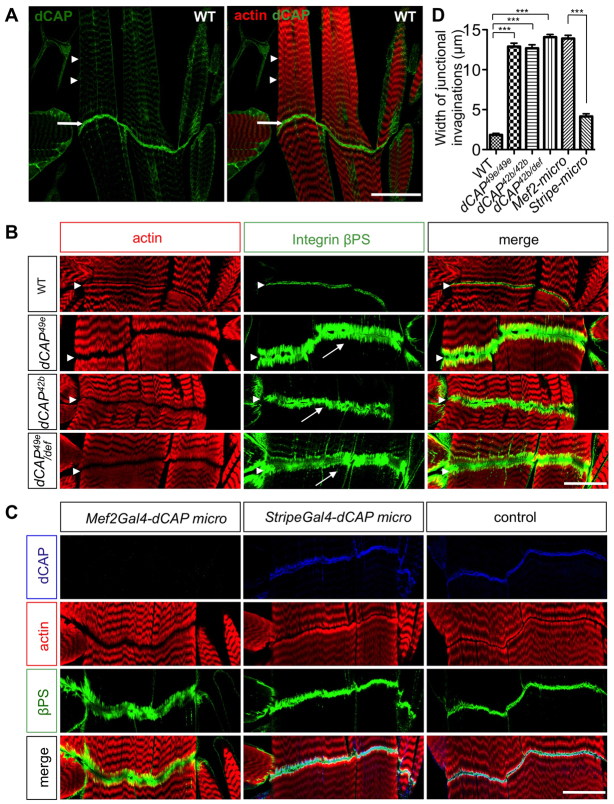

Fig. 5.

Muscle-attachment defects in CAP mutants. (A) Wild-type third instar larval fillet preparations immunostained with CAP antibody show CAP localization at the muscle Z-lines (arrowheads) and muscle-attachment sites (MASs) of muscles 6 and 7 (arrows). (B) Confocal images of larval MASs at muscles 6 and 7 stained with phalloidin and anti-βPS integrin. Arrowheads indicate MASs. Phalloidin staining reveals larger MAS gaps in CAP mutants. Numerous integrin-labeled junctional invaginations are presents in CAP mutants (arrows). (C) Larval fillets with cell-type-specific depletion of CAP, stained with indicated antibodies. (D) Quantification of MAS defects in larvae of indicated genotypes. Data are mean±s.e.m. Thirty abdominal segments (A2-A5) were analyzed for each experiment. ***P<0.005. Scale bars: 60 μm in A; 30 μm in B,C.

Prominent CAP localization is also found in embryonic chordotonal sensory organs, identified by the five scolopale cells of the pentascolopidial organ in each embryonic hemisegment (Fig. 2C). We immunostained wild-type and dCAP49e embryos with CAP antibodies and the 22C10 monoclonal antibody, which stains chordotonal neurons (Fujita et al., 1982). These experiments show that CAP is expressed specifically in scolopale cells, which envelop the dendrites of chordotonal neurons (Fig. 2C). In dCAP49e embryos, we observed no anti-CAP chordotonal immunostaining (Fig. 2D). In third instar larvae, CAP is also localized in chordotonal organs, predominantly within scolopale cells but also weakly in cap cells (Fig. 3A,B). The MAS, Z-disk and scolopale cell-specific localization of CAP is also recapitulated by a CAP GFP-trap transgenic line (Buszczak et al., 2007), which harbors a GFP transgene in the endogenous CAP genomic locus that expresses a CAP-GFP fusion protein (supplementary material Fig. S1B,C). Thus, in embryonic and larval developmental stages, CAP localizes to two actin-rich structures: MASs and chordotonal organ scolopale cells (Todi et al., 2004).

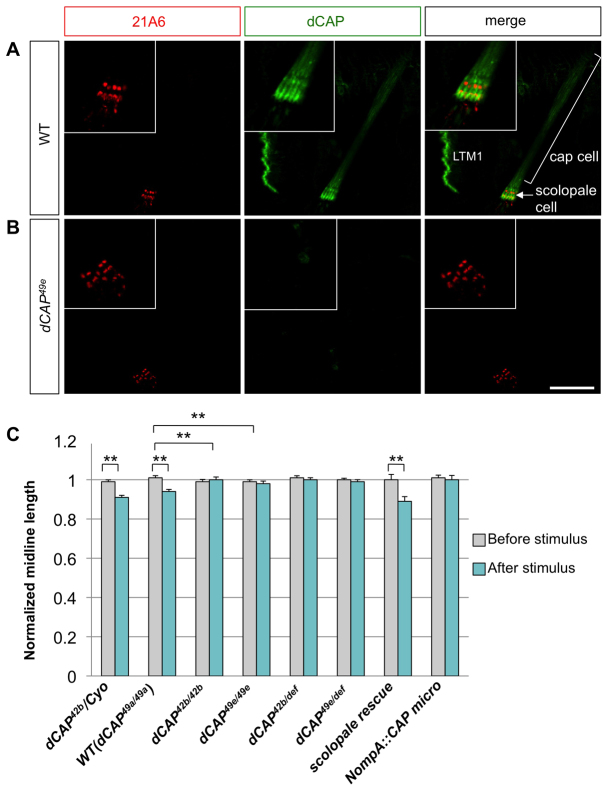

Fig. 3.

Vibration sensation defects in CAP mutants. (A,B) Wild-type and dCAP49e larvae immunostained with anti-CAP (green) and 21A6 antibody (red) (which labels Eys/Spam, an extracellular matrix protein inside the scolopale space). Anti-CAP labels scolopale cells and lateral transverse muscle (LTM1) MASs. (C) Normalized midline length of larvae of indicated genotypes before and after exposure to vibration stimuli (n=100 larvae per genotype); data are mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01. Scale bar: 30 μm.

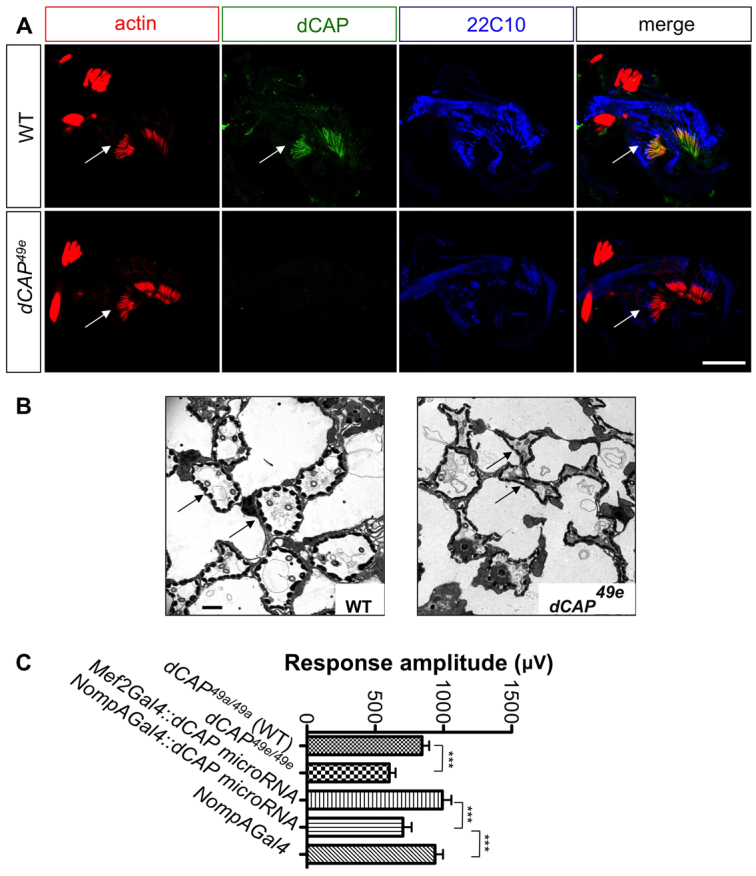

CAP is required for larval chordotonal organ function

We next performed a recently described behavioral assay that provides a sensitive readout of chordotonal organ-mediated locomotor response to vibration (Swierczek et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011). Fly chordotonal organs are mechanosensory organs that mediate proprioception in larvae and transduction of acoustic signals in adults (Caldwell et al., 2003; Eberl, 1999). Wild-type third instar larvae exhibit a characteristic biphasic vibration response. Larvae first display a fast startle response to vibration by hunching their bodies, followed by a second, relatively slower, head-turning response. These responses are largely dependent on the chordotonal sensory neurons and can be precisely quantified (Wu et al., 2011). The ‘hunch’ response to vibration is quantified by measuring the average larval body length reduction. The mean normalized larval body length is measured over the larval midline before and after a stimulus: for control dCAP49a (precise excision) larvae, this was 1.01±0.11 (before) and 0.94±0.1 (after); for dCAP42b heterozygotes, it was 0.99±0.07 (before) and 0.91±0.07 (after) (n=100 larvae for each genotype) (Fig. 3C). Thus, wild-type larvae show a significant (P<0.01) reduction in mean normalized body length in response to vibration. By contrast, dCAP49e and dCAP42b mutant larvae do not exhibit a significant hunching response to vibration (Fig. 3C). The mean normalized midline body length before and after stimuli for dCAP49e was 0.99±0.08 (before) and 0.98±0.1 (after); and for dCAP42b mutants it was 0.99±0.08 (before) and 1±0.09 (after) (n=100 larvae per genotype). This same phenotype was also observed when dCAP42b or dCAP49e alleles were placed in trans to a large chromosomal deficiency spanning the entire CAP locus (Fig. 3C). Scolopale cell-specific expression of CAP rescues this vibration-sensation defect observed in CAP mutants, and scolopale cell depletion of CAP by driving CAP miRNA using the NompA-Gal4 driver (Chung et al., 2001) phenocopies CAP mutants (Fig. 3C).

CAP is also enriched at the cap cell attachment site to the ectoderm (but not in ligament cells) (supplementary material Fig. S2A-B″). Integrin is also enriched at these sites. We examined βPS integrin localization in cap cells of dCAP49e mutants, and in dCAP49e mutants integrin localization in cap cells and the overall morphology of chordotonal organs, revealed by anti-85e-tubulin labeling, is apparently normal (supplementary material Fig. S2C-D″). These results suggest chordotonal defects observed in dCAP49e mutants arise primarily from the lack of scolopale cell CAP.

Structural and functional Johnston's organ defects in adult CAP mutants

We next examined a distinct chordotonal organ class: the adult Johnston's organ. The Johnston's organ resides in the second antennal segment and is composed of ~250 scolopidia (Todi et al., 2004). Johnston's organ scolopidia and larval chordotonal organs show remarkable morphological similarities. Several proteins, including Atonal and Beethoven, serve specialized functions in both of these organs (Caldwell et al., 2003; Todi et al., 2004). CAP is strongly expressed in wild-type Johnston's organs but not in dCAP49e mutants (Fig. 4A). Immunostaining with phalloidin, which illuminates Johnston's organ scolopale rods (Todi et al., 2004), and with the 22C10 mAb, which labels sensory neurons, reveals CAP in Johnston's organ scolopale cells, similar to our observations in embryonic chordotonal organs (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Audition defects in CAP mutants. (A) Antennal sections at the level of Johnston's organ from wild type and dCAP49e mutants immunostained with phalloidin (red), anti-CAP (green) and 22C10 antibody (blue). CAP colocalizes with phalloidin, which stains actin rods in scolopale cells (arrows). (B) Electron microscopic images of ultrathin sections from wild-type and dCAP49e Johnston's organs. CAP mutants show dysmorphic and collapsed scolopale cells (arrows). (C) Sound-evoked potentials recorded from the auditory nerves of adult flies. dCAP49e mutants (n=27 animals) and flies lacking CAP specifically in scolopale cells (n=21 animals) show a reduction in amplitude of response to sound when compared with controls (t-test: ***P<0.005). Data are mean±s.e.m. Scale bars: 30 μm in A; 1 μm in B.

Electrophysiological analyses to detect auditory responses were performed by recording from the auditory nerve following a mating song stimulus (Eberl et al., 2000; Eberl and Kernan, 2011). The electrophysiological response to mating songs was significantly diminished in dCAP49e mutants. The average response amplitude for dCAP49a (precise excision control) was 843±52 μV, compared with 603±46 μV in CAP mutants (n=27 animals per genotype) (Fig. 4C). We next depleted CAP from all scolopale cells in adult flies by expressing CAP miRNA under the control of the NompA-Gal4 driver (Chung et al., 2001). This resulted in a significant reduction in response amplitude: 703±63 μV, compared with 991±65 μV when the same CAP miRNA is driven in muscles (n=21 animals for each genotype).

We next examined larval chordotonal and adult Johnston's organ morphologies using several markers, including the 21A6 mAb (described above), NompA-GFP (which labels the extracellular matrix in the scolopale space, called the dendritic cap) (Chung et al., 2001), and anti-neurexin (which labels cell junctions between scolopale cells and also those between scolopale and CAP cells) (Baumgartner et al., 1996). None of these markers revealed obvious abnormalities in CAP mutant embryos or larvae (supplementary material Fig. S3A; data not shown). However, ultrastructural transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of Johnston's organ revealed that CAP mutant scolopale cells are dysmorphic and appear collapsed and ruptured (Fig. 4B). This is in sharp contrast to wild-type Johnston's organs, in which scolopale cells appear circular in cross-section, are of equal size and show fairly regular spacing (Fig. 4B). This morphological defect is consistent with CAP maintaining cytoskeletal structural integrity. In addition, sensory neurons in CAP mutant Johnston's organs often show accumulation of vacuolar structures (supplementary material Fig. S3B). As CAP localizes predominantly to scolopale cells, these defects are probably secondary to scolopale cell morphological defects and may result from partial disruption of the lymph environment surrounding sensory neuron dendrites in the Johnston's organ. Taken together, these data show that CAP mutants exhibit functional and morphological Johnston's organ deficits; the highly localized expression of CAP in scolopale cells, both in Johnston's organ and the larval chordotonal organ, implicates CAP in the regulation and/or maintenance of scolopale cell membrane morphology.

CAP mutants exhibit morphological defects at somatic body wall muscle attachment sites

As CAP is robustly localized to embryonic and larval muscle attachment sites (MASs), we next examined the morphology of MASs in CAP mutants. As shown by immunostaining for βPS integrin (an integral component of the MAS) and also for actin, stage 16 embryonic MASs in CAP mutants appear normal (Fig. 2F; data not shown). However, in third instar larvae, we find significant morphological abnormalities in CAP mutants. Filleted preparations of dCAP49e third instar larvae were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to determine MAS actin localization. In wild-type larvae, the somatic body wall MAS is bounded on either side by a smooth band of actin (Fig. 5B). Phalloidin staining also reveals that adjacent muscles are apposed to one another with a small gap, of uniform width over its entire length, separating adjacent body wall muscles. By contrast, actin organization at the MAS in CAP mutant larvae is severely disrupted, resulting in a jagged boundary at the gap where the MAS is located (Fig. 5B); this is in stark contrast to the smooth boundaries at this gap observed in wild-type larvae. Furthermore, we observed a significantly enlarged gap between actin filaments from adjacent muscles at most MASs in these mutants (Fig. 5B). We examined MAS morphology between lateral-ventral somatic muscles 6 and 7 in abdominal segments (A2-A5). For each genotype, 30 hemisegments from five to seven larvae were scored, revealing that this phenotype is fully penetrant in both dCAP49e and dCAP42b mutants.

At wild-type MASs, integrin subunits are localized to a smooth, compact band lining the narrow gap between muscles of adjacent segments (Fig. 5B). However, in CAP mutants this band of integrin staining is much broader and includes numerous invaginations into adjacent muscles (Fig. 5B). The average length of the integrin-positive invaginations into the muscles adjacent to the MAS in wild-type larvae is 2±0.18 μM; in dCAP49e mutants it is dramatically increased to 13±0.42 μM (n=30 hemisegments per genotype) (Fig. 5D). The penetrance and expressivity of this phenotype were not enhanced when the dCAP49e allele was placed in trans to a deficiency spanning the entire CAP genomic region, indicating that dCAP49e is either a null, or a very strong loss-of-function, allele (Fig. 5D). In addition, MASs in CAP mutants show partial detachments in ~25% of larval hemisegments, a phenotype suggesting partial disruption of integrin function.

The MAS is composed of two different cell types: multinucleated muscle fibers and tendon cells that connect the muscle fiber to the body wall (Brown, 2000). To determine which of these cell types require CAP function, we selectively depleted CAP by driving expression of the CAP tandem miRNAs transgene in muscle cells using the Mef2-Gal4 driver (Ranganayakulu et al., 1996), or in tendon cells using the stripe-Gal4 driver (Dorfman et al., 2002). Strikingly, CAP MAS localization was almost completely abolished when CAP miRNAs were expressed under control of Mef2-Gal4, whereas CAP localization was unaltered when CAP miRNAs were driven by stripe-Gal4 (Fig. 5C). Therefore most, if not all, MAS CAP protein is derived from muscles in third instar larvae. miRNA-mediated muscle-specific depletion of CAP phenocopies all attributes of the dCAP49e phenotype, both qualitatively and quantitatively, providing further evidence that CAP function in muscles is required for MAS cytoskeletal organization (Fig. 5C,D). Selective removal of CAP in tendon cells did not result in actin organization defects, but it did result in a somewhat broader integrin distribution. However, this phenotype is mild compared with muscle-specific depletion of CAP, or with CAP mutants (Fig. 5B-D). We speculate that the mild integrin localization defects we observed using stripe-Gal4 driven CAP miRNA arise from loss of CAP function in tendon cells at earlier stages of development. Importantly, we do not observe leaky expression of stripe-Gal4 in muscle cells (data not shown). We also examined dCAP49e mutant MASs in lateral transverse muscles. Unlike longitudinal muscles, which are attached both to tendon cells and to the muscles in the next segment, lateral transverse muscles are attached to the body wall only through tendon cells. Lateral transverse MASs appear normal in dCAP49e mutants (supplementary material Fig. S4A), suggesting that CAP is essential for the assembly of muscle-muscle junctions but is dispensable for muscle-tendon cell junctions.

CAP mutants also exhibit two additional defects. First, near the muscle cell surface, aberrant muscle structure (supplementary material Fig. S4B, arrow), with Z-lines oriented perpendicular to the MAS (as opposed to the horizontally aligned Z-lines observed in control animals), is observed in ~30% of dCAP49e larvae (n=30) (supplementary material Fig. S4B). Second, close to the muscle membrane, the parallel arrangement of actomyosin filaments is disrupted (arrowhead) in ~15% of CAP mutants (n=30) (supplementary material Fig. S4B, arrowhead). Lateral adhesions between muscles are normal in CAP mutants. Taken together, these data show that CAP, unlike certain integrin signaling components, is dispensable for initial assembly of the MAS but is required for MAS development and maybe also maintenance later in development.

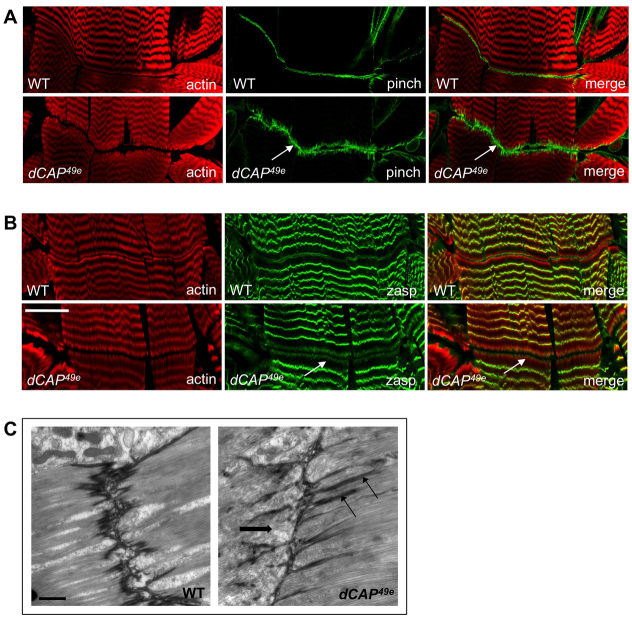

Altered distribution of integrin signaling components at the MAS in CAP mutants

Mammalian CAP proteins are implicated in integrin signaling (Kioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006), so we next investigated whether CAP functions to assemble integrin signaling complex components. We examined the distribution of MAS extracellular matrix proteins tiggrin and thrombospondin (Bunch et al., 1998; Subramanian et al., 2007), integrin subunits and the integrin signaling proteins pinch, Ilk and zasp (Geiger and Yamada, 2011; Jani and Schöck, 2007) at the CAP mutant MAS (Fig. 6A,B; supplementary material Fig. S5; and data not shown). We observed no difference in the levels or colocalization of these proteins at MASs in CAP mutants. However, each of these integrin-associated proteins displays the aberrant, broad, MAS distribution accompanied by numerous aberrant invaginations into adjacent muscles that we observe for βPS integrin expression in CAP mutants and CAP miRNA knock-down larvae (Fig. 6A,B; supplementary material Fig. S5; and data not shown).

Fig. 6.

MASs in CAP mutant larvae exhibit altered distribution of integrin signaling components. (A) Wild-type and dCAP49e larvae stained with anti-Pinch and phalloidin. (B) Wild-type and dCAP49e larvae stained with anti-Zasp; both Pinch and Zasp show a broader distribution in CAP mutants compared with the control animals (arrows in A,B). (C) Electron microscopic images of muscle-attachment sites from wild-type and dCAP49e 3rd instar larvae reveal larger junctional invaginations in the dCAP49e animals (arrows) and also myofilament disorganization (thick arrow). Scale bars: 30 μm in A,B; 2 μm in C.

To better characterize the ectopic CAP mutant MAS junctional invaginations revealed by anti-βPS integrin immunostaining, we examined MAS ultrastructure in wild-type and CAP mutant third instar larvae using TEM. We found that close to the muscle cell membrane, myofilaments at MASs are disorganized in CAP mutants (Fig. 6C, thick arrow). Furthermore, we observe numerous junctional invaginations in CAP mutant animals that are larger than those seen in wild-type larvae (Fig. 6C). This is commensurate with our light-level observations of MASs in CAP mutants (Fig. 5B). The presence of these significantly enlarged membranous infoldings, and also the cytoskeletal defects observed in our ultrastructural analysis, suggests that CAP regulates cytoskeletal organization and affects muscle membrane morphology at MASs.

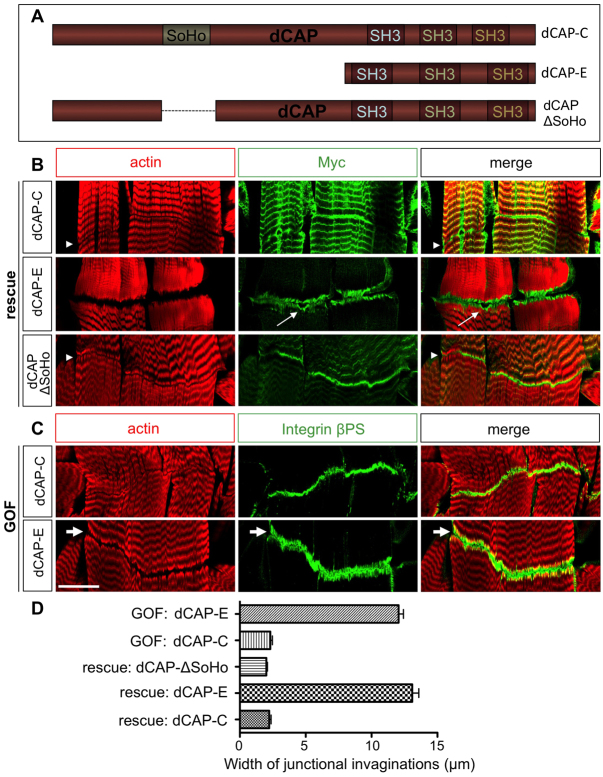

Distinct functions of CAP isoforms at larval MASs

CAP protein isoforms are observed from insects to mammals (Kioka et al., 2002). Therefore, we next assessed different CAP isoforms for rescue of CAP mutant MAS defects using cell-type-specific expression in vivo. We assessed rescue ability of a CAP isoform called CAP-C, which includes all CAP protein domains, and also the smaller CAP isoform, CAP-E, which includes only the C-terminal SH3 domains (Fig. 7A). In our immunoblotting experiments, the presence of 100 kDa and 30 kDa bands, which are close to the expected sizes of CAP isoforms C and E, respectively, suggests that these isoforms are found in vivo (Fig. 1D). When expressed in muscles using the Mef2-Gal4 driver, myc-tagged CAP-C fully rescues the MAS defects observed in CAP mutants (Fig. 7B,D). However, there are differences in the distribution of the Mef2-Gal4-driven CAP-C isoform and endogenous CAP protein. The CAP-C isoform is localized evenly to both Z-lines and MASs, whereas endogenous CAP protein shows preferential targeting to MASs (compare Fig. 7B and Fig. 5A). The CAP-E isoform possesses only the three CAP SH3 domains and no additional CAP N-terminal domains, and it does not rescue the CAP MAS phenotype (Fig. 7A,B,D). Interestingly, this isoform is localized predominantly to MASs and not to the Z-lines (Fig. 7B). Therefore, regions of N-terminal CAP are required for targeting CAP protein to Z-lines, whereas the CAP C-terminal SH3 domains are sufficient for targeting to the MAS. Furthermore, though the N-terminal CAP protein motifs are dispensable for targeting to the MAS, these motifs are required for CAP function at MAS, given the inability of the CAP-E isoform to rescue CAP mutants. We also observed that a CAP isoform lacking the conserved SoHo domain is able to rescue the CAP MAS phenotype (Fig. 7B,D). Therefore, the SoHo domain is not required for CAP function at the MAS.

Fig. 7.

Muscle-specific expression of CAP rescues MAS defects in CAP mutants. (A) Domain organization of different CAP protein isoforms. (B) Myc-tagged versions of CAP isoforms were expressed using the Mef2-Gal4 driver in a dCAP49e homozygous background; larval fillets were stained with phalloidin and anti-Myc. Muscle-specific expression of the large, but not the small, isoform rescues the CAP phenotype (arrowheads). The short CAP-E CAP isoform localizes to MASs, but not to the Z-lines (arrows). (C) Wild-type larvae overexpressing CAP-E or the full-length CAP-C isoforms were immunostained with phalloidin and anti-βPS integrin, revealing MAS defects similar to CAP mutants following CAP-E, but not CAP-C, overexpression (arrows). n=30 hemisegments. (D) Quantification of MAS defects in larvae. Data are mean±s.e.m. Scale bars: 30 μm.

Muscle-specific overexpression of full-length CAP-C, or the CAP-C isoform lacking the SoHo domain, did not result in MAS defects, either at embryonic or third instar larval stages (Fig. 7C,D; data not shown). However, overexpression of the short CAP isoform (CAP-E), which includes only the C-terminal SH3 domains, did lead to defects in actin organization and integrin distribution at MASs that were very similar to those observed in CAP mutants (Fig. 7C,D). Though these CAP-E gain-of-function defects are not enhanced by removal of one copy of CAP (supplementary material Fig. S6), co-expression of full-length CAP-C and also CAP-E suppresses these defects (supplementary material Fig. S6). Therefore, the short CAP isoform acts in vivo in a dominant-negative fashion, probably through sequestration of CAP-associated proteins, thereby inhibiting endogenous CAP function.

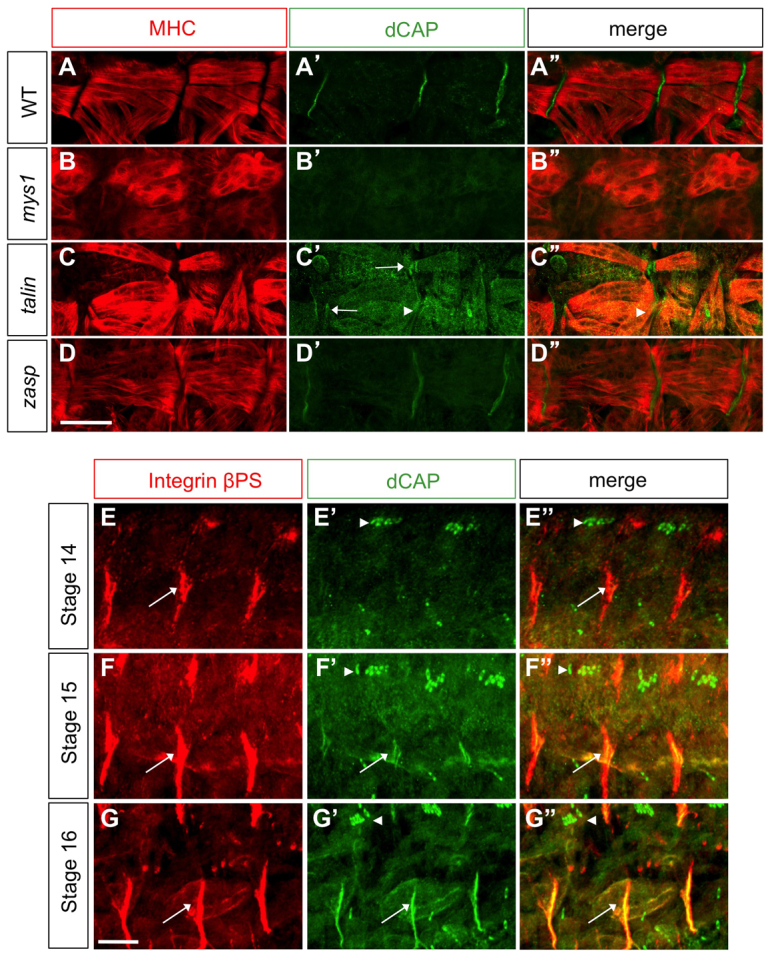

Integrin and Talin are required for CAP recruitment to the embryonic MAS

To examine CAP recruitment, or stabilization, at the larval MAS, we examined its localization in embryos lacking integrin-signaling pathway components. Wild-type embryos show robust CAP localization at MASs (Fig. 2E; Fig. 8A′). βPS integrin mutants (mys1) exhibit the classic myospheroid phenotype (Brown et al., 2000). MAS CAP localization is missing in mys1 mutants (Fig. 8B-B″). This is also consistent with integrin recruitment to MASs prior to CAP recruitment, whereas CAP recruitment to scolopale cells (arrowheads) is independent of integrins (Fig. 8E-G″). In stage 14 embryos, integrin is expressed at the MAS but CAP is not. At stage 15, CAP expression is observed in regions of the MAS, whereas, at stage 16, CAP expression completely colocalizes with βPS integrin (Fig. 8E-G″).

Fig. 8.

Integrin and Talin requirements for CAP localization at MASs. (A-A″) Wild-type, (B-B″) β-PS integrin, (C-C″) talin and (D-D″) Zasp mutant embryos immunostained with anti-CAP and anti-MHC. CAP localization at MASs is absent in β-PS integrin (mys1) mutants and is reduced (arrowheads) in talin mutants, which also show MAS splitting (arrow). (E-G″) Wild-type embryos of various stages stained with βPS integrin and CAP antibodies to label MASs (arrows) and scolopale cells (arrowheads). Scale bars: 10 μm.

CAP localization in talin mutants (rhea1) (Brown et al., 2002) reveals a dramatic decrease in CAP MAS levels, though a low level of CAP expression is still detectable at MASs in these mutants. These mutants often show MAS splitting, observable by CAP localization in two bands, not one (Fig. 8C′, white arrows). This may reflect partial detachment of muscles from the body wall. We also examined CAP localization in embryos lacking zasp, which is implicated in integrin signaling (Jani and Schöck, 2007), and we find that CAP MAS localization is unperturbed, both at stage 16 and 17 (Fig. 8D). Thus, both integrin and Talin are required for proper localization of CAP at the embryonic MASs, suggesting CAP signals downstream of integrins at the MAS.

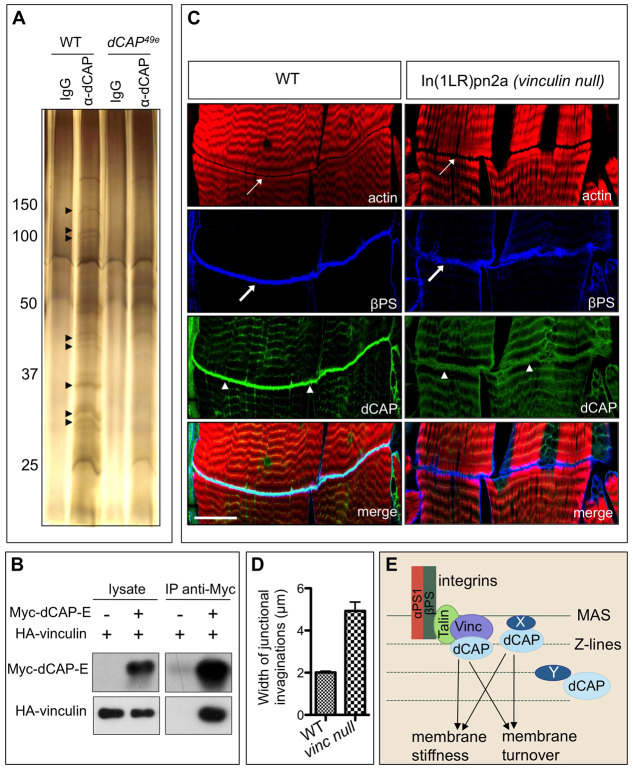

Depletion of Vinculin results in MAS defects and disruption of CAP MAS localization

There are several known CAP-interacting proteins, including Flotillin, Tensin, Filamin and Paxillin (Kioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007). We used null mutants or RNAi-mediated knockdown to determine whether any of these proteins phenocopy CAP mutants; however, none did (supplementary material Fig. S7A). We then sought to identify proteins required for CAP function, immunopurifying endogenous CAP from wild-type and CAP Drosophila embryo lysates using our CAP polyclonal antibody. We isolated protein bands present in wild-type, but not the CAP mutant, immunoprecipitates (Fig. 9A). These bands were pooled and sequenced using MALDI TOF mass spectrometry. The most enriched protein in CAP immunoprecipitates (aside from CAP itself), as indicated by the number of peptides corresponding to any particular protein, was Vinculin. We also identified Talin as a CAP-interacting protein. The other proteins identified in CAP immunoprecipitates were 5-oxo-prolinase, Nervous wreck, 14-3-3ε and histone H2A.

Fig. 9.

CAP interacts with Vinculin, and Vinculin depletion partially phenocopies CAP mutants. (A) Silver-stained PAGE showing anti-CAP immunoprecipitates from wild-type and CAP embryonic lysates. Arrowheads indicate bands specific to wild-type lysates. (B) Myc-tagged CAP-E immunoprecipitates HA-tagged Vinculin when co-expressed in S2R+ cells. (C) vinculin mutants show a reduction in CAP levels at the MASs (arrowheads). MASs in vinculin mutant larvae show aberrant cytoskeletal organization (top panels, thin arrows), and increased βPS integrin-labeled junctional infoldings at MASs (blue, thick arrows). (D) Quantification of MAS defects in larvae. Data are mean±s.e.m. (E) Schematic of CAP function and recruitment of key signaling molecules. Scale bar: 30 μm.

Vinculin interacts with all mammalian CAP proteins in vitro (Kioka, 2002; Kioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006); however, the functional significance of this interaction is unknown. We expressed HA-tagged Vinculin with, or without, Myc-CAP-E (the CAP isoform consisting only SH3 domains) in S2R+ cells and immunoprecipitated CAP with Myc antibodies. We found that immunoprecipitation of Myc-CAP-E using anti-Myc robustly co-immunoprecipitated HA-Vinculin (Fig. 9B). We next examined a chromosomal inversion (In(1LR)pn2a) that disrupts the vinculin gene (Alatortsev et al., 1997). We first assessed the significance of Vinculin-CAP interactions in audition by electrophysiological recordings from auditory nerves of wild-type and vinculin mutant flies, and did not observe any significant difference in sound evoked potentials between wild type and vinculin mutants (supplementary material Fig. S7B). This suggests that CAP functions in chordotonal organs in a Vinculin-independent manner. However, MASs in vinculin mutants show with full penetrance a marked reduction in CAP levels, though CAP Z-band localization remains unaltered (Fig. 9C). We observed similar morphological defects in In(1LR)pn2a homozygous mutants and in animals carrying this mutation over a deficiency that includes the entire vinculin gene, suggesting the phenotypic defects in In(1LR)pn2a homozygous mutants result from complete disruption of vinculin (data not shown). This suggests Vinculin plays a crucial role in the recruitment of CAP to the MAS, reminiscent of Vinculin-dependent recruitment of CAP to mammalian focal adhesions (Takahashi et al., 2005). Examination of actin staining in vinculin mutants reveals that, as in CAP mutants, the actin bands lining the MAS are serrated and flank a gap wider than that observed in wild-type animals (Fig. 9C,D). However, this gap is not as wide as in CAP mutants, and vinculin mutants show fewer βPS integrin-labeled junctional invaginations relative to CAP mutants (Fig. 9C,D). These results show that CAP and its binding partner Vinculin function together as key regulators of cytoskeletal organization and membrane morphology at the MAS.

DISCUSSION

Integrin-based adhesion complexes are crucial for cell attachment to the extracellular matrix. These complexes change their composition and architecture in response to extracellular forces, initiating downstream signaling events that regulate cytoskeletal organization (Geiger et al., 2009). Here, we have investigated the role played by the CAP protein in two stretch-sensitive structures in Drosophila: the MAS and the chordotonal organ. CAP mutants exhibit aberrant junctional invaginations at the MAS and collapse of scolopale cells in chordotonal organs. Our study highlights a crucial integrin signaling function during development: the maintenance of membrane morphology in stretch-sensitive structures.

CAP functions in somatic muscles

The morphological defects observed in CAP mutants could result from an excessive integrin signaling, or possibly accumulation of additional membranous components related to integrin signaling, in CAP mutants, owing to defects in endocytosis at the MAS. This is consistent with known interactions between CAP family members and vesicle trafficking regulators, including Dynamin and Synaptojanin, which are required for internalization of transmembrane proteins (Cestra et al., 2005; Tosoni and Cestra, 2009) (Fig. 9E). Alternatively, CAP may be required for proper organization of the actin cytoskeleton at MASs, and the aberrant membrane invaginations we observe are a secondary consequence of these cytoskeletal defects. This idea garners support from known interactions between CAP and various actin-binding proteins, including Vinculin, Paxillin, Actinin, Filamin and WAVE2 (Cestra et al., 2005; Kioka, 2002; Kioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006). A third possibility is that CAP and Vinculin are regulators of membrane stiffness at the MAS, and aberrant junctional infoldings observed in CAP and vinculin mutants derive from diminished membrane rigidity in the presence of persistent myofilament contractile forces (Fig. 9E) (Diez et al., 2011; Goldmann et al., 1998). Biophysical studies demonstrate that Vinculin-deficient mammalian cells in vitro show reduced membrane stiffness (Goldmann et al., 1998). Interestingly, the CAP protein ArgBP2 interacts with Spectrin, a protein important for cell membrane rigidity maintenance (Cestra et al., 2005). These models for CAP function at MASs, however, are not mutually exclusive. Interestingly, disruption of the ECM protein Tiggrin leads to MAS phenotypes similar to CAP. Future studies on CAP interaction with Tiggrin and other CAP-interacting proteins will shed light on mechanisms underlying CAP function. Nevertheless, we demonstrate here in vivo the importance of CAP in stretch-sensitive organ morphogenesis, and it will be interesting to determine whether this function is phylogenetically conserved.

Role of CAP in chordotonal organs

Apart from the MAS, CAP is also expressed at high levels in chordotonal organ scolopale cells, and we find that CAP mutants are defective in vibration sensation, a hallmark of chordotonal organ dysfunction. However, only the initial fast hunching response to vibration is disrupted in CAP mutant larvae. This may result from a partial loss of chordotonal function in these organs in the absence of CAP. We also observe a functional defect in the adult Johnston's organ; CAP mutant flies show diminished sound-evoked potentials. Importantly, the scolopale cells in CAP mutants appear partially collapsed. The extracellular space within the scolopale cell is lined by an actin cage, and CAP may influence the proper assembly of this actin cage or its association with the scolopale cell membrane. Ch organs are mechanosensory detectors and are constantly exposed to tensile forces. Thus, CAP apparently influences cytoskeletal integrity in two actin-rich structures: the MAS and the chordotonal organ, both of which are involved in force transduction.

CAP interaction with Vinculin

Mammalian and Drosophila CAP bind to Vinculin (Kioka, 2002; Kioka et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2006). Vinculin is required for the recruitment of the mammalian CAP protein vinexin to focal adhesions in NIH3T3 cells in vitro (Takahashi et al., 2005). Consistent with this observation, we observe a dramatic decrease in CAP levels at MASs in vinculin mutants, but residual levels of CAP protein remain. Furthermore, CAP localization at the muscle fiber Z-lines is completely unaltered in vinculin mutants. These observations indicate that Vinculin is not the sole upstream regulator of CAP localization (Fig. 9E). vinculin mutants show some of the phenotypic defects we observe in CAP mutants; however, these defects are less pronounced. Therefore, the residual CAP pool that is recruited to MASs in a Vinculin-independent manner is apparently sufficient for partial CAP function. Our assessment of CAP and Vinculin function at the larval MAS shows that these proteins are required for maintaining the integrity of junctional membranes in the face of tensile forces. CAP proteins may serve as scaffolding proteins at membrane-cytoskeleton interfaces and facilitate the assembly of protein complexes involved in cytoskeletal regulation and membrane turnover (Fig. 9E).

Mutations in the CAP-binding protein filamin cause myofibrillar myopathy (Vorgerd et al., 2005). This, in combination with our data showing a crucial role for CAP in regulation of muscle morphology, sets the stage for investigating how loss of CAP protein function might influence the etiology of myopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington and Vienna Stock Centers for reagents. We are grateful to S. Craig for comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01 NS35165 to A.L.K., R01 DC004848 and P30 DC010362 to D.F.E. and S. H. Green] and by Janelia Farm Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) funding to M.Z. M.Z. is a Fellow at the Janelia Farm HHMI; A.L.K. is an Investigator of the HHMI. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.085100/-/DC1

References

- Alatortsev V. E., Kramerova I. A., Frolov M. V., Lavrov S. A., Westphal E. D. (1997). Vinculin gene is non-essential in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 413, 197-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S., Littleton J. T., Broadie K., Bhat M. A., Harbecke R., Lengyel J. A., Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Prokop A., Bellen H. J. (1996). A Drosophila neurexin is required for septate junction and blood-nerve barrier formation and function. Cell 87, 1059-1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj R., Qi W., Yu H. (2004). Identification of two novel components of the human NDC80 kinetochore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13076-13085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bökel C., Brown N. H. (2002). Integrins in development: moving on, responding to, and sticking to the extracellular matrix. Dev. Cell 3, 311-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent J. R., Werner K. M., McCabe B. D. (2009). Drosophila larval NMJ dissection. J. Vis. Exp. 24, 1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H. (2000). Cell-cell adhesion via the ECM: integrin genetics in fly and worm. Matrix Biol. 19, 191-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H., Gregory S. L., Martin-Bermudo M. D. (2000). Integrins as mediators of morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 223, 1-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H., Gregory S. L., Rickoll W. L., Fessler L. I., Prout M., White R. A., Fristrom J. W. (2002). Talin is essential for integrin function in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 3, 569-579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch T. A., Graner M. W., Fessler L. I., Fessler J. H., Schneider K. D., Kerschen A., Choy L. P., Burgess B. W., Brower D. L. (1998). The PS2 integrin ligand tiggrin is required for proper muscle function in Drosophila. Development 125, 1679-1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M., Paterno S., Lighthouse D., Bachman J., Planck J., Owen S., Skora A. D., Nystul T. G., Ohlstein B., Allen A., et al. (2007). The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics 175, 1505-1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J. C., Eberl D. F. (2002). Towards a molecular understanding of Drosophila hearing. J. Neurobiol. 53, 172-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J. C., Miller M. M., Wing S., Soll D. R., Eberl D. F. (2003). Dynamic analysis of larval locomotion in Drosophila chordotonal organ mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 16053-16058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carisey A., Ballestrem C. (2011). Vinculin, an adapter protein in control of cell adhesion signalling. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 157-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson S. D., Hilgers S. L., Juang J. L. (1997). Ultrastructure and blood-nerve barrier of chordotonal organs in the Drosophila embryo. J. Neurocytol. 26, 377-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cestra G., Toomre D., Chang S., De Camilli P. (2005). The Abl/Arg substrate ArgBP2/nArgBP2 coordinates the function of multiple regulatory mechanisms converging on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1731-1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Huang H., Ward C. M., Su J. T., Schaeffer L. V., Guo M., Hay B. A. (2007). A synthetic maternal-effect selfish genetic element drives population replacement in Drosophila. Science 316, 597-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang S. H., Baumann C. A., Kanzaki M., Thurmond D. C., Watson R. T., Neudauer C. L., Macara I. G., Pessin J. E., Saltiel A. R. (2001). Insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation requires the CAP-dependent activation of TC10. Nature 410, 944-948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y. D., Zhu J., Han Y., Kernan M. J. (2001). nompA encodes a PNS-specific, ZP domain protein required to connect mechanosensory dendrites to sensory structures. Neuron 29, 415-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. A., McGrail M., Beckerle M. C. (2003). Analysis of PINCH function in Drosophila demonstrates its requirement in integrin-dependent cellular processes. Development 130, 2611-2621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez G., Auernheimer V., Fabry B., Goldmann W. H. (2011). Head/tail interaction of vinculin influences cell mechanical behavior. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 406, 85-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman R., Shilo B. Z., Volk T. (2002). Stripe provides cues synergizing with branchless to direct tracheal cell migration. Dev. Biol. 252, 119-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du T., Zamore P. D. (2007). Beginning to understand microRNA function. Cell Res. 17, 661-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl D. F. (1999). Feeling the vibes: chordotonal mechanisms in insect hearing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 389-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl D. F., Kernan M. J. (2011). Recording sound-evoked potentials from the Drosophila antennal nerve. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011, prot5576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl D. F., Hardy R. W., Kernan M. J. (2000). Genetically similar transduction mechanisms for touch and hearing in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 20, 5981-5988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S. C., Zipursky S. L., Benzer S., Ferrús A., Shotwell S. L. (1982). Monoclonal antibodies against the Drosophila nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 7929-7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Yamada K. M. (2011). Molecular architecture and function of matrix adhesions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B., Spatz J. P., Bershadsky A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 21-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann W. H., Galneder R., Ludwig M., Xu W., Adamson E. D., Wang N., Ezzell R. M. (1998). Differences in elasticity of vinculin-deficient F9 cells measured by magnetometry and atomic force microscopy. Exp. Cell Res. 239, 235-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grashoff C., Hoffman B. D., Brenner M. D., Zhou R., Parsons M., Yang M. T., McLean M. A., Sligar S. G., Chen C. S., Ha T., et al. (2010). Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 466, 263-266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg N., Patzak I., Willenbrock F. (2011). The insider's guide to leukocyte integrin signalling and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 416-426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hytönen V. P., Vogel V. (2008). How force might activate talin's vinculin binding sites: SMD reveals a structural mechanism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbal A., Volk T., Salzberg A. (2004). Recruitment of ectodermal attachment cells via an EGFR-dependent mechanism during the organogenesis of Drosophila proprioceptors. Dev. Cell 7, 241-250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani K., Schöck F. (2007). Zasp is required for the assembly of functional integrin adhesion sites. J. Cell Biol. 179, 1583-1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikouchi A., Inagaki H. K., Effertz T., Hendrich O., Fiala A., Göpfert M. C., Ito K. (2009). The neural basis of Drosophila gravity-sensing and hearing. Nature 458, 165-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan M. J. (2007). Mechanotransduction and auditory transduction in Drosophila. Pflugers Arch. 454, 703-720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N. (2002). [A novel adaptor protein family regulating cytoskeletal organization and signal transduction – Vinexin, CAP/ponsin, ArgBP2]. Seikagaku 74, 1356-1360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N., Sakata S., Kawauchi T., Amachi T., Akiyama S. K., Okazaki K., Yaen C., Yamada K. M., Aota S. (1999). Vinexin: a novel vinculin-binding protein with multiple SH3 domains enhances actin cytoskeletal organization. J. Cell Biol. 144, 59-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N., Ueda K., Amachi T. (2002). Vinexin, CAP/ponsin, ArgBP2: a novel adaptor protein family regulating cytoskeletal organization and signal transduction. Cell Struct. Funct. 27, 1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioka N., Ito T., Yamashita H., Uekawa N., Umemoto T., Motoyoshi S., Imai H., Takahashi K., Watanabe H., Yamada M., et al. (2010). Crucial role of vinexin for keratinocyte migration in vitro and epidermal wound healing in vivo. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 1728-1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniewski L. A., Hosch S. E., Neels J. G., de Luca C., Pashmforoush M., Lumeng C. N., Chiang S. H., Scadeng M., Saltiel A. R., Olefsky J. M. (2007). Bone marrow-specific Cap gene deletion protects against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 13, 455-462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandai K., Nakanishi H., Satoh A., Takahashi K., Satoh K., Nishioka H., Mizoguchi A., Takai Y. (1999). Ponsin/SH3P12: an l-afadin- and vinculin-binding protein localized at cell-cell and cell-matrix adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 144, 1001-1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto T., Kain K. H., Ginsberg M. H. (2004). Neurobiology: new connections between integrins and axon guidance. Curr. Biol. 14, R121-R123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. H. (1994). Imaging neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole-mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. Methods Cell Biol. 44, 445-487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran P., Budnik V. (2010). Electron microscopy of Drosophila larval neuromuscular junctions. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, doi:10.1101/pdb.prot5474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganayakulu G., Schulz R. A., Olson E. N. (1996). Wingless signaling induces nautilus expression in the ventral mesoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 176, 143-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Wayburn B., Bunch T., Volk T. (2007). Thrombospondin-mediated adhesion is essential for the formation of the myotendinous junction in Drosophila. Development 134, 1269-1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierczek N. A., Giles A. C., Rankin C. H., Kerr R. A. (2011). High-throughput behavioral analysis in C. elegans. Nat. Methods 8, 592-598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Mitsushima M., Okada N., Ito T., Aizawa S., Akahane R., Umemoto T., Ueda K., Kioka N. (2005). Role of interaction with vinculin in recruitment of vinexins to focal adhesions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336, 239-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todi S. V., Sharma Y., Eberl D. F. (2004). Anatomical and molecular design of the Drosophila antenna as a flagellar auditory organ. Microsc. Res. Tech. 63, 388-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todi S. V., Franke J. D., Kiehart D. P., Eberl D. F. (2005). Myosin VIIA defects, which underlie the Usher 1B syndrome in humans, lead to deafness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15, 862-868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosoni D., Cestra G. (2009). CAP (Cbl associated protein) regulates receptor-mediated endocytosis. FEBS Lett. 583, 293-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorgerd M., van der Ven P. F., Bruchertseifer V., Löwe T., Kley R. A., Schröder R., Lochmüller H., Himmel M., Koehler K., Fürst D. O., et al. (2005). A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin c causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 297-304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt F. M., Fujiwara H. (2011). Cell-extracellular matrix interactions in normal and diseased skin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Sweeney L. B., Ayoob J. C., Chak K., Andreone B. J., Ohyama T., Kerr R., Luo L., Zlatic M., Kolodkin A. L. (2011). A combinatorial semaphorin code instructs the initial steps of sensory circuit assembly in the Drosophila CNS. Neuron 70, 281-298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yack J. E. (2004). The structure and function of auditory chordotonal organs in insects. Microsc. Res. Tech. 63, 315-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H., Nusse R. (2002). Identification of DCAP, a drosophila homolog of a glucose transport regulatory complex. Mech. Dev. 119, 115-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H., Yanagawa S. (2003). Axin and the Axin/Arrow-binding protein DCAP mediate glucose-glycogen metabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304, 229-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorozu S., Wong A., Fischer B. J., Dankert H., Kernan M. J., Kamikouchi A., Ito K., Anderson D. J. (2009). Distinct sensory representations of wind and near-field sound in the Drosophila brain. Nature 458, 201-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas C. G., Gregory S. L., Brown N. H. (2001). Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1007-1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Liu J., Cheng A., Deyoung S. M., Chen X., Dold L. H., Saltiel A. R. (2006). CAP interacts with cytoskeletal proteins and regulates adhesion-mediated ERK activation and motility. EMBO J. 25, 5284-5293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Liu J., Cheng A., Deyoung S. M., Saltiel A. R. (2007). Identification of CAP as a costameric protein that interacts with filamin C. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4731-4740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.