Inflammation is a complex biological response, protecting the host and promoting homeostasis following mechanical, chemical or microbial insults. Epithelia are strategically located at the interface between the external and internal milieu where, collectively, their ability to establish a specialized and dynamic cytoarchitecture, to express an impressive array of relevant receptors and their associated signal transduction pathways, and to signal to resident and migrant cellular effectors of inflammation and immunity allows them to actively participate in the inception and subsequent regulation of inflammatory and immune responses (Segre, 2006; Swamy et al., 2010). The pace of progress in identifying new effectors and mechanisms in epithelial-based immunity has been fast and furious in recent years (Nestle et al., 2009; Swamy et al., 2010) in part as a result of a growing effort to understand the pathophysiology of relevant diseases and to foster the development of novel therapeutic strategies. In this issue, Roth et al. present evidence that adds to the emerging role for keratin cytoskeletal proteins in the regulation of epidermal immunity and skin barrier function (see this issue of J. Cell. Sci., Roth et al. 5269-5279).

Keratins belong to the large family of intermediate filament (IF)-forming proteins. Two distinct subtypes of keratin, the acidic type I (n = 28) and basic type II (n = 26) keratins (Schweizer et al., 2006), assemble in a pairwise and obligatory fashion to form 10-nm-wide filaments. Keratin filaments are typically organized into intricate networks integrated at sites of cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion, as well as at the surface of the nucleus in epithelial cells (Coulombe and Lee, 2012). The differentiation-related and context-dependent regulation of keratin genes and proteins in epithelia is an evolutionarily conserved, defining property of these unique cytoskeletal elements. Genetic and biochemical evidence supports two main roles for keratins and other IF proteins: first, a general and context-independent role of providing mechanical support, the abrogation of which leads to fragile cells and accounts for a broad range of diseases and, second, the regulation of basic metabolic processes (e.g. cell survival, growth and death) in a context-specific manner that reflects interactions between IF proteins and key effectors of signaling pathways (Coulombe and Lee, 2012; Omary et al., 2004). The perturbation of such non-mechanical functions is likely to have a significant role in the modification of pathogenic traits in several types of human disease.

Roth et al. provide evidence for a new and unanticipated role of keratin 1 (Krt1) – the main differentiation-specific type II keratin expressed in the epidermis – in regulating innate immunity in the skin (Roth et al., 2012). Similar to mice that lack Krt10 –the type I partner of Krt1 (Reichelt and Magin, 2002) – Krt1-null mice do not show obvious signs of cell fragility in the suprabasal, differentiating layers of epidermis. However, unlike mice that are deficient in Krt10, Krt1-null mice exhibit a spectacular inflammatory disease phenotype with skin-specific and systemic components, further substantiating the now solid trend that the two members of a keratin filament can have distinct biological roles. Although the epidermis of newborn Krt1-null mice is intact and appears histologically normal at birth, the inside–out barrier function is grossly defective with a severe reduction of intact cornified envelopes, reflecting aberrant terminal differentiation and leading to completely penetrant neonatal lethality. Unexpectedly, the skin of unchallenged Krt1-null mice exhibits a perinatal upregulation of numerous pro-inflammatory and innate immunity-associated cytokine mRNA transcripts compared with normal skin. Additionally, the serum levels of the IL-1 superfamily proinflammatory cytokine Il-18 are significantly upregulated in Krt1-null mice, suggesting a role for Krt1 in regulating both local and systemic inflammation. The mortality and diminution of cornified envelopes associated with the Krt1-null phenotype can both be rescued, in part, by pharmacologically or genetically blunting the expression of IL-18. Roth et al. go on to show that Krt1 participates in the regulation of IL-18 production and release in a keratinocyte-specific and inflammasome-dependent manner (Fig. 1).

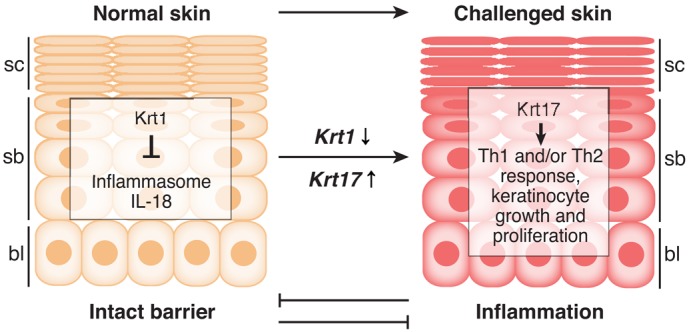

Fig. 1.

Krt1 and Krt17 regulate epidermal immunity in a distinct and context-dependent manner. Normal epidermis expresses Krt1 in the differentiating suprabasal layers, where it contributes to skin barrier homeostasis, in part by preventing the activation of the inflammasome and the processing of IL-18 (Roth et al., 2012). Upon an acute or chronic challenge to the epidermal barrier (e.g. injury, environmental irritants or cancer), several genes, including Krt17, are robustly induced in basal and suprabasal keratinocytes at the expense of Krt1 (and other differentiation-specific genes). Krt17 actively modulates intracellular signaling pathways to stimulate protein synthesis (Kim et al., 2006) and to also polarize the inflammatory response towards Th1 and/or Th17 (DePianto et al., 2010), thereby promoting keratinocyte growth and proliferation. Inflammation and normal barrier function thus can antagonize one another. bl, basal layer; sb, suprabasal layers; sc, stratum corneum (barrier proper).

Despite the lack of cell lysis, the compromised epidermal barrier and occasional presence of skin lesions in Krt1-null mice is reminiscent of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (a disorder also known as bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma), which arises in individuals who carry single, dominant-acting missense alleles in KRT1 or KRT10 (Omary et al., 2004). In addition, the authors draw parallels between the pro-inflammatory transcription profile observed in Krt1-null epidermis and that seen in atopic dermatitis (eczema) or psoriatic human skin, which both are characterized by a reduced expression of KRT1 and the concomitant upregulation of the wound-inducible keratins KRT6, KRT16 and KRT17 (Freedberg et al., 2001; Segre, 2006).

The study by Roth et al. in this issue adds significantly to a growing body of evidence highlighting a role in immunomodulation for select keratins in various epithelial contexts. In the simple epithelial lining of the mouse gut, for instance, loss of Krt8 causes hyperplasia and colitis with increased T-cell recruitment to the colon and upregulation of T-helper (Th) 2 cytokines (Habtezion et al., 2005). Targeted deletion of Krt5 in mouse leads to acute epidermal fragility along with massive, lethal skin blistering immediately after birth. This phenotype is remarkably similar to what occurs in epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), a genetic disorder that results from function-abrogating mutations in either KRT5 or its partner KRT14 (Coulombe and Lee, 2012). Prior to birth, the skin of late-stage mouse Krt5-null embryos is mechanically sound in utero, but already shows elevated expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines Il-6 and Il-1β (Lu et al., 2007) and Ccl2 and Ccl20, correlating with an increased density of antigen-presenting Langerhans dendritic cells in their epidermis (Roth et al., 2009). Coincidentally, individuals that suffer from EBS as a result of mutations at the KRT5 locus show an increased density of Langerhans cells in the epidermis, a phenomenon that is not seen in EBS cases that are associated with KRT14 mutations or in Krt14-null mice (Roth et al., 2009). Finally, the genetic loss of Krt17 results in a delay in the inception of basaloid tumors in Gli2 transgenic mouse skin, which correlates with reduced tumor keratinocyte proliferation and a global cytokine switch, from what should be a Th1- and/or Th17-dominated to a Th2-dominated immune profile, in skin tumors (DePianto et al., 2010) (Fig. 1). In particular, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Cxcl5, Cxcl9 and Cxcl11, which are produced by and mitogenic for keratinocytes and are otherwise known to have a role in the pathogenesis of basal cell carcinoma in humans (Lo et al., 2010), exhibit a Krt17-dependent and keratinocyte-autonomous regulation in mouse skin keratinocytes (DePianto et al., 2010).

Further validation for the role of select keratin proteins in the regulation of skin barrier function and inflammation originated from a systems genetics analysis of cancer susceptibility in mouse skin. Quigley et al. (Quigley et al., 2009) found that Krt1, Krt6b (which is co-regulated with Krt17 in several settings), the obscure Krt78 and, to a lesser extent, Krt6a and Krt16, are all part of a gene and linkage network that integrates barrier function, inflammation and susceptibility to two-step chemical carcinogenesis in mouse (of note, glabrous skin of Krt16-null mice exhibit a compromised barrier function with minimal cell lysis) (Lessard and Coulombe, 2012). The absence of Krt5 and Krt17 from this ‘barrier–inflammation–cancer’ network is likely to be a reflection of their strong constitutive expression in skin tissue sites that have been analyzed in the study by Quigley and colleagues (Quigley et al., 2009). Additional members of this network, including S100a8 and Defb3, are also markedly upregulated in Krt1-null skin.

Collectively, these studies open a new chapter in the rapidly evolving inventory of keratin function in skin epithelia: the regulation of inflammatory- and immune-based processes. The mechanistic relationship(s) between these various keratins and inflammation are likely to be complex. For instance, Krt1 and Krt17 have, broadly speaking, opposing roles in promoting inflammation in the epidermis, and tend to be regulated in opposite directions (with expression of Krt17 up and Krt1 down) in the context of psoriasis, non-melanoma skin cancer and related disease processes (Freedberg et al., 2001) (Fig. 1). Going forward, the mechanisms that govern the newly defined keratin-barrier–inflammation–disease axis need to be deciphered to achieve a deeper understanding of how keratins and the immune system collaborate at the biochemical, cellular and systemic levels towards the promotion of normal tissue homeostasis or of pathogenic processes.

Footnotes

Funding

Relevant efforts in the Coulombe laboratory are supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number AR044232 and CA160255]. R.H. received support from NIH training [grant number T32 CA009110].

References

- Coulombe P. A., Lee C. H. (2012). Defining keratin protein function in skin epithelia: epidermolysis bullosa simplex and its aftermath. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 763–775 10.1038/jid.2011.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePianto D., Kerns M. L., Dlugosz A. A., Coulombe P. A. (2010). Keratin 17 promotes epithelial proliferation and tumor growth by polarizing the immune response in skin. Nat. Genet. 42, 910–914 10.1038/ng.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg I. M., Tomic–Canic M., Komine M., Blumenberg M. (2001). Keratins and the keratinocyte activation cycle. J. Invest. Dermatol. 116, 633–640 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habtezion A., Toivola D. M., Butcher E. C., Omary M. B. (2005). Keratin-8-deficient mice develop chronic spontaneous Th2 colitis amenable to antibiotic treatment. J. Cell Sci. 118, 1971–1980 10.1242/jcs.02316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Wong P., Coulombe P. A. (2006). A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth. Nature 441, 362–365 10.1038/nature04659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J. C., Coulombe P. A. (2012). Keratin 16-null mice develop palmoplantar keratoderma, a hallmark feature of pachyonychia congenita and related disorders. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 1384–1391 10.1038/jid.2012.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo B. K., Yu M., Zloty D., Cowan B., Shapiro J., McElwee K. J. (2010). CXCR3/ligands are significantly involved in the tumorigenesis of basal cell carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2435–2446 10.2353/ajpath.2010.081059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Chen J., Planko L., Zigrino P., Klein–Hitpass L., Magin T. M. (2007). Induction of inflammatory cytokines by a keratin mutation and their repression by a small molecule in a mouse model for EBS. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 2781–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle F. O., Di Meglio P., Qin J. Z., Nickoloff B. J. (2009). Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 679–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary M. B., Coulombe P. A., McLean W. H. (2004). Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2087–2100 10.1056/NEJMra040319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley D. A., To M. D., Pérez–Losada J., Pelorosso F. G., Mao J. H., Nagase H., Ginzinger D. G., Balmain A. (2009). Genetic architecture of mouse skin inflammation and tumour susceptibility. Nature 458, 505–508 10.1038/nature07683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt J., Magin T. M. (2002). Hyperproliferation, induction of c-Myc and 14-3-3sigma, but no cell fragility in keratin-10-null mice. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2639–2650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth W., Reuter U., Wohlenberg C., Bruckner–Tuderman L., Magin T. M. (2009). Cytokines as genetic modifiers in K5-/- mice and in human epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Hum. Mutat. 30, 832–841 10.1002/humu.20981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth W., Kumar V., Beer H-D., Richter M., Wohlenberg C., Reuter U., Thiering S., Staratschek–Jox A., Hofmann A.Kreusch, et al. (2012). Keratin 1 maintains skin integrity and participates in an inflammatory network in skin via interleukin-18. J. Cell Sci. 1255269–5279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer J., Bowden P. E., Coulombe P. A., Langbein L., Lane E. B., Magin T. M., Maltais L., Omary M. B., Parry D. A., Rogers M. A.et al. (2006). New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J. Cell Biol. 174, 169–174 10.1083/jcb.200603161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre J. A. (2006). Epidermal barrier formation and recovery in skin disorders. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1150–1158 10.1172/JCI28521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy M., Jamora C., Havran W., Hayday A. (2010). Epithelial decision makers: in search of the ‘epimmunome’. Nat. Immunol. 11, 656–665 10.1038/ni.1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]