Abstract

Cell type–specific gene expression in humans involves complex interactions between regulatory factors and DNA at enhancers and promoters. Mapping studies for expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), transcription factors (TFs) and chromatin markers have become widely used tools for identifying gene regulatory elements, but prediction of target genes remains a major challenge. Here, we integrate genome-wide data on TF-binding sites, chromatin markers and functional annotations to predict genes associated with human eQTLs. Using the random forest classifier, we found that genomic proximity plus five TF and chromatin features are able to predict >90% of target genes within 1 megabase of eQTLs. Despite being regularly used to map target genes, proximity is not a good indicator of eQTL targets for genes  150 kilobases away, but insulators, TF co-occurrence, open chromatin and functional similarities between TFs and genes are better indicators. Using all six features in the classifier achieved an area under the specificity and sensitivity curve of 0.91, much better compared with at most 0.75 for using any single feature. We hope this study will not only provide validation of eQTL-mapping studies, but also provide insight into the molecular mechanisms explaining how genetic variation can influence gene expression.

150 kilobases away, but insulators, TF co-occurrence, open chromatin and functional similarities between TFs and genes are better indicators. Using all six features in the classifier achieved an area under the specificity and sensitivity curve of 0.91, much better compared with at most 0.75 for using any single feature. We hope this study will not only provide validation of eQTL-mapping studies, but also provide insight into the molecular mechanisms explaining how genetic variation can influence gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

Regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes involves multiple transcription factors (TFs) and cofactors acting on DNA at specific genomic loci defined as regulatory elements. Given the complexity of genomes in higher organisms such as humans, the program for this process is even more difficult to decipher (1,2). The first steps toward understanding the regulatory program involve determining the target specificity of TFs that are modulated by interactions with other factors and by the local chromatin structure. Many of these interactions occur in promoter regions that are in proximity to the transcription start sites (TSS) of target genes. Yet, in recent years, experimental evidence has shown that interactions between regulatory elements and target genes can occur over long genomic distances (3–5).

The importance of distal gene regulatory elements for coordinating cell type–specific expression of their target genes has motivated whole-genome surveys of different human cell types. The ENCODE consortium is an international collaborative effort initially set up to build a comprehensive list of all functional elements in the human genome (6). Since then, the consortium has identified cis-regulatory elements (CREs) in a wide variety of cell types (7). The identification of these regulatory elements through mapping protein–DNA interactions has been greatly accelerated by the advent of high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation assays like ChIP-seq. The majority of TFs profiled by ChIP-seq have >50% of their binding sites beyond 2.5 kilobases (kb) of a TSS. By combining binding site data on multiple TFs across cell types, the relationship between TFs and genomic features can be revealed (8). However, not all TF-binding sites detected in a particular cell may localize at active regulatory elements. To detect activated elements, DNase-seq and FAIRE-seq (Formaldehyde Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) are used to map genomic regions of open chromatin. The co-localization of TF-binding sites with open chromatin sites gives more confidence to the location of regulatory elements, where most of the cell type–specific sites are typically located away from the TSS (9,10).

Despite the vast array of assays to detect regulatory elements, it remains a challenge to identify their target genes. To date, the most common approach used in computational and experimental studies of regulatory elements has been based on genomic distance. A target gene is mapped to a regulatory element if it is the nearest or if it is within a genomic distance threshold. Although it is often the case that genes in proximity to a regulatory element are targets (11–14), there are many important genes regulated by distal elements. One example is the sonic hedgehog gene (Shh), which is regulated by an enhancer located 1 megabase (Mb) upstream (15). Another example is enhancers of c-Myc found in ‘gene deserts’ located a few hundred kilobases away from the nearest gene (16). Other genomic features like the preserved co-localization of genes on chromosomes of different species, or conserved synteny, are also considered, as it reflects co-evolution between regulatory elements and target genes (17,18). However, low conserved synteny is reported between upregulated genes and enhancers detected by ChIP-seq (19). For these reasons, there remains a need for a systematic approach of predicting and validating target genes of regulatory elements.

This area of research is limited by the paucity of in vivo data describing interactions between regulatory elements, such as enhancers, and target genes. Reporter assays, which place the element in question at the promoter of a reporter gene, allow investigation of enhancer activity (20,21), but do not capture the chromatin structure, which allows distal enhancers to interact with target genes. Because of this, methods to capture chromosome conformation were developed to provide evidence of long-range physical interactions (22,23). However, genome-wide data sets of chromosome conformation have a resolution on the order of megabases, too large to screen for interactions between multiple enhancers and target genes. A more indirect approach is to use co-variation between gene expression and enhancer-associated chromatin markers to map enhancers to target genes (24). It has been suggested to use markers of histone modification, such as H3K4me1, to identify active enhancers. But because H3K4me1 occurs ubiquitously along the genome, there are still too many potential enhancers that can be mapped to a particular gene. This means that such approaches lack the specificity needed to detect direct interactions between enhancers and targets. Nevertheless, analysis of histone modification sites has identified unique chromatin signatures for distal regulatory elements (24,25). The frequent positioning of disease-related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within regulatory elements defined by chromatin markers suggests that integrative modeling of multiple chromatin features may help decipher the connection between regulatory elements and diseases (24).

Another approach for finding associations between target genes and regulatory elements relies on analyzing SNPs. The decreased cost of genome sequencing has resulted in the identification of genetic variants in different individuals and cell types. Genome-wide association studies that compared genetic variants with the occurrence of disease have implicated numerous enhancer regions (26,27). This information on genotypes can also be analyzed together with gene expression data to find associations between specific genetic variants and gene expression levels as determined through expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) studies (28–30). Numerous validated regulatory elements have been identified using eQTL data, progressing the field of functional genomics (31). Because many SNPs in linkage disequilibrium could be associated with the expression of target genes, prediction of target genes using eQTL data suffers from the same low specificity as using chromatin markers. Efforts to integrate eQTL data with other genomic features have provided better estimates of the regulatory effect on target genes (32,33). In particular, Gaffney et al. (33) have shown that TF-binding sites and chromatin markers are enriched in regions with causal eQTL SNPs. Nevertheless, there exists no systematic study of how well associations found in eQTL studies agree with results from previously mentioned studies on TF binding and chromatin structure.

Addressing this question, we looked for putative regulatory elements defined by co-localization of TF-binding, chromatin signatures and eQTL signals. Using these elements, we present a method to predict their target genes. The method uses a combination of features as predictors, including genomic proximity, TF binding, gene expression, open chromatin, Gene Ontology (GO) similarities and insulators. We evaluated the performance of the target gene predictions using eQTL data from lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL), fibroblasts and T-cells (30). Our tests showed substantially higher accuracy for predictions made using a combination of features compared with using any single feature in isolation. Our method is particularly useful for finding additional target genes when eQTL studies are underpowered to do so. In addition, the features we use describe cis-interactions between regulatory elements and target genes. This is especially useful when trying to identify genes that are directly regulated by eQTLs rather than indirectly regulated through trans-interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TF-binding sites

We obtained ChIP-Seq data on the binding sites of 29 TFs plus “insulator associated DNA-binding protein,” CTCF in the GM12878 cell line from the ENCODE consortium (Additional file 1, Supplementary Table S1). Each data set contains a signal map of ChIP DNA fragments, where the signal height is the number of overlapping fragments at each nucleotide position in the genome (UCSC hg18). ChIP-seq signals mapped to hg19 were converted to hg18 coordinates using the UCSC liftover tool. Enrichment of genomic regions for protein binding was tested against a set of input DNA control (P

). Peaks indicating regions with sufficient signal above peak-height threshold (false discovery rate

). Peaks indicating regions with sufficient signal above peak-height threshold (false discovery rate  0.05) were identified using the PeakSeq algorithm (34). After conducting a genome-wide scan for peaks, we examined tracks of putative binding sites for each of the TFs. The position of each binding site was defined by the center of each ChIP-Seq peak. Adjacent binding sites that are within 500 bp of each other were grouped to form non-overlapping regions of TF-binding sites. The boundaries of each region are defined by the left-most and right-most binding sites.

0.05) were identified using the PeakSeq algorithm (34). After conducting a genome-wide scan for peaks, we examined tracks of putative binding sites for each of the TFs. The position of each binding site was defined by the center of each ChIP-Seq peak. Adjacent binding sites that are within 500 bp of each other were grouped to form non-overlapping regions of TF-binding sites. The boundaries of each region are defined by the left-most and right-most binding sites.

Chromatin marker data

A multivariate hidden Markov model was applied to the combinatorial patterns of nine histone modification markers to distinguish 15 chromatin states (24). The states were learned de novo on the basis of the patterns of chromatin marks and their spatial relationships in the GM12878 genome. Six broad classes of chromatin states were defined as promoter, enhancer, insulator, transcribed, repressed and inactive states. Within each class, active, weak and poised promoters (states 1–3) differ in expression level; strong and weak candidate enhancers (states 4–7) differ in expression of proximal genes; strongly and weakly transcribed regions (states 9–11) also differ in their positional enrichments along transcripts; and repressed, heterochromic and repetitive states (states 13–15) are enriched in H3K9me3. Regions with state annotations vary in length from 500 bp on average for promoter and enhancer states to 10 kb on average for inactive states. Open chromatin sites in GM12878 cell lines were profiled using FAIRE, and the data were downloaded from ENCODE. Enrichment of sequence fragments from FAIRE was identified using a feature density estimator, F-Seq (35). For each enriched region, the maximum F-Seq density signal value has been calculated, and P-values for peaks were determined by fitting the data to a gamma distribution. A P-value threshold of 0.01 was considered to be significant.

Gene expression data

The gene expression profiles of 38 distinct populations of human hematopoietic cells were downloaded from the Broad Institute DMap Project (36). Quantile normalization was applied across expression arrays, and the log expression intensities for each gene was mean centered. Probe sets were mapped to a gene’s TSS via transcript identifiers and probe set annotations provided by the Ensembl database (release 54). For cases where there were more than one probe set mapping to a gene’s TSS, we filtered for the probe set with the highest variance in log intensity values across cell samples. In total, 8968 genes were profiled in the data set.

eQTL data

Gene expression profiling and association testing with genetic variants was performed on primary fibroblasts, LCLs (Epstein–Barr virus–immortalized B cells) and T-cells from umbilical cords of 75 individuals of Western European origin (30). Dimas et al. (30) conducted association testing between genotypes and gene expression values using the Spearman rank correlation on all SNPs within a 2-Mb window centered on the TSS of each gene. After filtering for significance at the 0.001 threshold, there are 427, 442 and 430 genes with significant cis associations in fibroblasts, LCLs and T-cells, respectively. We extended the list of associated eQTL SNPs based on linkage disequilibrium with SNPs in CEU HapMap panels detected from the low-coverage sequencing pilot (Pilot 1) of the 1000 Genomes Project. The SNAP tool was used to find the additional SNPs that are above the correlation coefficient  threshold of 0.8 (37).

threshold of 0.8 (37).

Identifying candidate regulatory elements

Regions with chromatin state annotation were mapped to non-overlapping regions of TF-binding sites if they share any base pair. If two different chromatin state regions overlap with one TF-binding region, the chromatin state with the greater number of overlapping base pairs is mapped. All regions with co-localization of TF-binding sites and having chromatin state annotations were referred to as CREs (Supplementary Figure S1). The boundary of a CRE is defined by the left-most and right-most centers of TF binding peaks in a non-overlapping region. Because the width of a TF’s binding signal peak is estimated to be 200 bp, we assumed an eQTL SNP is likely to affect TF binding if it is within 100 bp from the center of the signal peak. We filtered for CREs with eQTL SNPs within 100 bases from the CREs’ boundaries, and used those to test for target gene prediction. CREs can be linked to multiple target genes if the co-localized eQTL SNPs are associated with different genes.

Genomic distances between regulatory element and target gene

For each gene within 1 Mb from the center of each CRE, we calculated the genomic distance between the gene’s TSS and the nearest associated eQTL SNP in the CRE. The positions of gene TSS are the same as those used in the mapping microarray probe sets to genes.

Modeling gene co-expression

We used a generalized additive model (GAM) to describe the relationship between potential target genes and the expression of TFs that occupy CREs (38). The GAM implementation in the R package ‘mgcv’ provides the option of smoothing spline functions for each predictor term, which gave us the flexibility of incorporating non-linear relationships between TFs and genes. For each gene–CRE pair, we considered a model with one or more additive functions:

|

(1) |

where  is the expected log expression of the target gene in cell type

is the expected log expression of the target gene in cell type  ,

,  is the mean expression set to zero,

is the mean expression set to zero,  is the log expression of TF

is the log expression of TF  in cell type

in cell type  ,

,  is the number of TFs in the CRE and

is the number of TFs in the CRE and  is a spline function, where the degree of smoothing is chosen by cross-validation in the mgcv package. As opposed to using linear predictors, the estimated non-parametric function can reveal non-linearities in the effect of TF on target gene. In this model, we also allow for second-order interactions where

is a spline function, where the degree of smoothing is chosen by cross-validation in the mgcv package. As opposed to using linear predictors, the estimated non-parametric function can reveal non-linearities in the effect of TF on target gene. In this model, we also allow for second-order interactions where  is a set of unknown partial bidimensional smoothing functions.

is a set of unknown partial bidimensional smoothing functions.

We modeled gene co-expression for every gene within 1 Mb of each CRE. For each CRE–gene pair, we inferred the parameters  ,

,  and

and  for the aforementioned equation using the expression profiles

for the aforementioned equation using the expression profiles  of the co-localized TFs

of the co-localized TFs  and

and  of the gene across samples

of the gene across samples  from the training set

from the training set  . We then predicted gene expression across the samples

. We then predicted gene expression across the samples  in the test set

in the test set  using the TF expression

using the TF expression  in those samples as predictors. The prediction step gave us a predicted gene expression value

in those samples as predictors. The prediction step gave us a predicted gene expression value  for each target gene in a sample

for each target gene in a sample  . The prediction accuracy was then measured by calculating the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient (denoted by

. The prediction accuracy was then measured by calculating the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient (denoted by  ) between the predicted expression

) between the predicted expression  and the observed expression

and the observed expression  for all samples in

for all samples in  . We also calculated the adjusted

. We also calculated the adjusted  for the model to estimate the proportion of gene expression variation in the training set

for the model to estimate the proportion of gene expression variation in the training set  explained by TF expression, while taking into account the number of predictors. The closer the

explained by TF expression, while taking into account the number of predictors. The closer the  is to 1, the better the model fit to the data. Whenever the regression line fits worse than the horizontal mean line,

is to 1, the better the model fit to the data. Whenever the regression line fits worse than the horizontal mean line,  is negative. This can easily happen for non-linear regressions. Five-fold cross-validation was performed to assess how well predictions would generalize to new sample data sets. The

is negative. This can easily happen for non-linear regressions. Five-fold cross-validation was performed to assess how well predictions would generalize to new sample data sets. The  and

and  values reported were averaged over the cross-validations. We used the

values reported were averaged over the cross-validations. We used the  value as a feature in the prediction of eQTL targets.

value as a feature in the prediction of eQTL targets.

TF co-occurrence

When we examined the non-overlapping regions of TF-binding sites, we counted the different pairs of TFs co-localized to the same region. The co-occurrence between pairs of TFs  and

and  is measured by the log-odds score of the observed number of regions containing the binding site pairs

is measured by the log-odds score of the observed number of regions containing the binding site pairs  over the expected number

over the expected number  .

.

| (2) |

To estimate the expected number of pairs, we repeatedly permuted ( ) the TF labels for each TF-binding site and then recounted the pairs of TFs. The average number of pairs from all recounts after permutations is the expected number of pairs.

) the TF labels for each TF-binding site and then recounted the pairs of TFs. The average number of pairs from all recounts after permutations is the expected number of pairs.

|

(3) |

We use the co-occurrence score for different pairs of TFs to measure the co-occurrence between TFs binding in a CRE and TFs binding to the promoter region (±1 kb from TSS) of a gene. Calculating the overall co-occurrence score between the two sets of TFs,  and

and  , is analogous to maximum weighted matching for bipartite graphs. If we define an indicator variable

, is analogous to maximum weighted matching for bipartite graphs. If we define an indicator variable  for each edge between a TF

for each edge between a TF  and a TF

and a TF  , the weights are the co-occurrence score for TF pairs

, the weights are the co-occurrence score for TF pairs  .

.

| (4) |

This sum is used as a feature for classifying whether the gene is a target or non-target. Genes without any TF-binding sites in the promoter region is assigned the minimum overall score recorded for genes with TF-binding sites.

Regions of open chromatin

Identified FAIRE peaks were mapped to a gene’s promoter if the center of the FAIRE peak is within 1 kb of the gene’s TSS. The FAIRE signal value was used as a feature for eQTL target prediction. A higher signal indicated that chromatin is open in the promoter region and the gene is more likely to be a target. Genes without a detected FAIRE peak at the promoter region were assigned a signal value of 0.

GO similarity

The information content (IC) of a GO term  is defined by

is defined by  , where

, where  is the probability of GO term

is the probability of GO term  occurring. The GO database provides an association table mapping genes to GO terms. We compute

occurring. The GO database provides an association table mapping genes to GO terms. We compute  as the number of genes annotated by GO term t divided by the total number of annotated genes. The pairwise similarity between GO terms

as the number of genes annotated by GO term t divided by the total number of annotated genes. The pairwise similarity between GO terms  and

and  was calculated as the IC of their most informative common ancestor from the set of all common ancestors

was calculated as the IC of their most informative common ancestor from the set of all common ancestors  .

.

| (5) |

We then searched the GO database to find GO terms  mapped to the gene

mapped to the gene  within 1 Mb of a CRE, and GO terms

within 1 Mb of a CRE, and GO terms  mapped to the gene

mapped to the gene  encoding a TF that binds to the CRE. As previously proposed (39), we assigned each GO term

encoding a TF that binds to the CRE. As previously proposed (39), we assigned each GO term  occurring in gene

occurring in gene  to its best matching partner

to its best matching partner  in gene

in gene  to calculate the GO similarity measure

to calculate the GO similarity measure  .

.

| (6) |

When the TF and the target gene have an unequal number of GO terms, multiple terms in gene  can be assigned to one term from TF

can be assigned to one term from TF  , and the result may be different for

, and the result may be different for  . Therefore, we take

. Therefore, we take  as the symmetric version of GO similarity. For CREs with multiple TFs, the average similarity between the gene and TFs was used for target prediction.

as the symmetric version of GO similarity. For CREs with multiple TFs, the average similarity between the gene and TFs was used for target prediction.

Insulators as enhancer-blocking elements

We used CTCF-binding sites as markers for the position of insulators that prevent interaction between a CRE and a gene. For each gene, we examined the genomic region in between the TSS and the nearest TF-binding site of a CRE. The CTCF binding peaks were called from the GM12878 ChIP-Seq data provided by ENCODE, and we averaged the signal values across all peaks within the region. If no CTCF binding peaks were found, the signal value was set to zero. The average signal value was used as a feature for target gene prediction.

Prediction of target genes

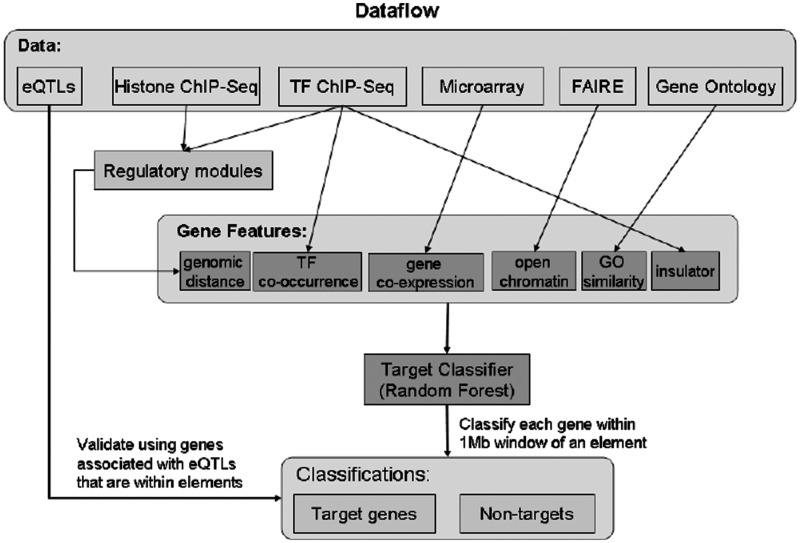

For each gene whose TSS is 1 Mb upstream or downstream from either side of a CRE, we predicted whether that gene is a target of a eQTL SNP within the CRE. Some or all the features used for prediction were combined by a random forest classifier to decide whether a single gene is a target of an eQTL SNP (Figure 1). We used the implementation of random forests in the R package ‘randomForest’ (version 4.6-6) and trained a random forest of 500 randomly generated decision trees. At each node of a decision tree, the classifier splits the data using a randomly chosen subset of  features, where

features, where  is the total number of features given to the classifier. The classifier uses the Gini index to determine the best split at each node. The classifier learns to classify each gene as either ‘target’ or ‘non-target’ and outputs the ratio of trees voting ‘target’ for each gene. The same cutoff ratio

is the total number of features given to the classifier. The classifier uses the Gini index to determine the best split at each node. The classifier learns to classify each gene as either ‘target’ or ‘non-target’ and outputs the ratio of trees voting ‘target’ for each gene. The same cutoff ratio  was applied to all genes when making final predictions. Implementation of random forest classifier for eQTL target prediction can be found at http://sysbio.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/eqtlPredictor.

was applied to all genes when making final predictions. Implementation of random forest classifier for eQTL target prediction can be found at http://sysbio.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/eqtlPredictor.

Figure 1.

An ensemble framework based on random forests that integrates diverse data sets in the context of TF and chromatin features. After pre-processing the data, we identified CREs using TF binding and histone modification data. The classifier combined models based on six features of gene, TF and chromatin structure to make predictions of whether genes 1 Mb upstream and downstream of each CRE are targets or non-targets. The binary classification is validated by genes associated with eQTLs that are within the CREs.

Evaluating prediction performance

To evaluate the classification of genes using a specified cutoff  , we calculated three performance statistics:

, we calculated three performance statistics:

|

Sensitivity, also known as recall, indicates the proportion of target genes that are predicted correctly, and precision denotes the probability that a prediction for a target gene is correct. Because both sensitivity and precision only evaluate classification of target genes, we also assess specificity, which measures the proportion of non-targets that are predicted correctly. To evaluate the overall performance of each classifier for various  values, we used the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, AUC, as the probability that a classifier will assign a higher target probability score to a randomly chosen target gene than to a randomly chosen non-target gene. Alternatively, the F measure combines precision and recall by representing the harmonic mean of the two measures:

values, we used the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, AUC, as the probability that a classifier will assign a higher target probability score to a randomly chosen target gene than to a randomly chosen non-target gene. Alternatively, the F measure combines precision and recall by representing the harmonic mean of the two measures:

To control for overfitting and test the classifier on new data, we partitioned the CREs into 10 subsets. Of the 10 subsets, 9 were used for training, and the remaining was used for testing. The cross-validation process was repeated 10 times, where each of the 10 subsets was used only once for testing. The values presented for sensitivity, specificity, precision and AUC are the means over the 10-fold cross-validations. Only for the case of predicting eQTL targets in fibroblasts and T-cells did we not cross-validate, as we trained only on LCL data and tested on other cell types.

RESULTS

TF and histone modifications co-localize with eQTLs

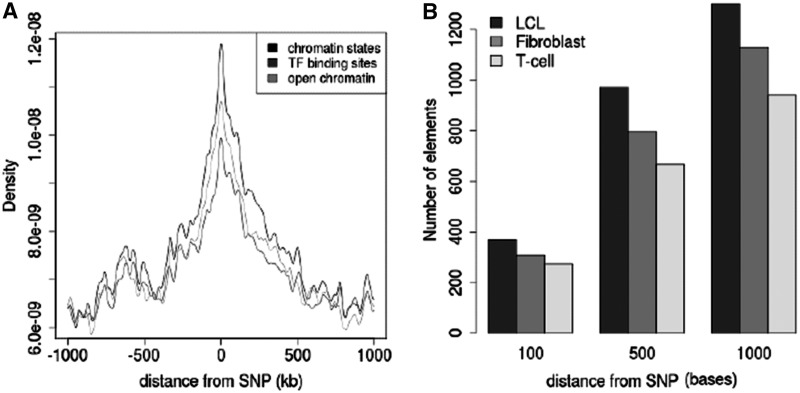

Analysis of binding sites for 29 different TFs (Additional file 1, Supplementary Table S1) from the GM12878 (lymphoblastoid) cell line revealed 221 926 non-overlapping regions with one or more distinct TF-binding sites. Of those, 221 653 regions are annotated to have distinct chromatin states as defined by histone modifications. These regions with both histone modification markers and TFs positioned near the same site, which we call candidate CREs, are quite common throughout the genome (10,25,40). However, it is unclear as to what extent eQTLs are co-localized with these regions. We examined the locations of 551 eQTL SNPs significantly associated with the expression of genes in LCL cells (30). Figure 2A shows the densities of TF-binding sites, histone modifications and open chromatin signals relative to genomic distance from the eQTL SNPs. Regions closer to eQTLs seem to have a higher occurrence of TF and chromatin marks. Since the eQTL data set was published, additional genotyping data became available through the 1000 Genomes Project (41). Therefore, we expanded the list of eQTL SNPs to 10 719 by adding proxy SNPs based on linkage disequilibrium. Analysis of CRE locations in relation to eQTL SNPs showed 1303 CREs positioned within 1000 bases of eQTL SNPs, 971 CREs within 500 bases and 369 CREs within 100 bases. Similar across all three cell types is the distribution of eQTL SNPs around CREs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of TF and chromatin features around eQTL SNPs in the LCL cell. Chromatin states, as defined by histone modification markers, also co-localize with TF-binding sites and sites of open chromatin. (B) Number of CREs detected from GM12878 data that co-localize with eQTL SNPs in three different cell types. The level of co-localization depends on the distance between the SNP and the nearest TF in the CRE.

Gene co-expression is a weak predictor of distal genes

Reconstruction of gene regulatory networks often made the assumption that the regulatory potential of a TF on a gene decreases the further away it is from the gene (42,43). Network edges were inferred using the expression of TFs to find associations with the expression of target genes, which we refer to as co-expression. Therefore, we examined the expression of 29 TFs binding to CREs to see whether this assumption holds and to see whether there is potential in predicting target genes based on co-expression. The expression profiles of TFs across 38 distinct hematopeitic cell types were compared with the expression profiles of potential target genes near CREs. Regression analysis was used to fit TF expression to target gene expression, and then the expressions of target genes were predicted for different conditions. We applied GAMs to the gene expression data, as it is well suited for describing non-linear relationships between the expression profiles of TFs and target genes (44).

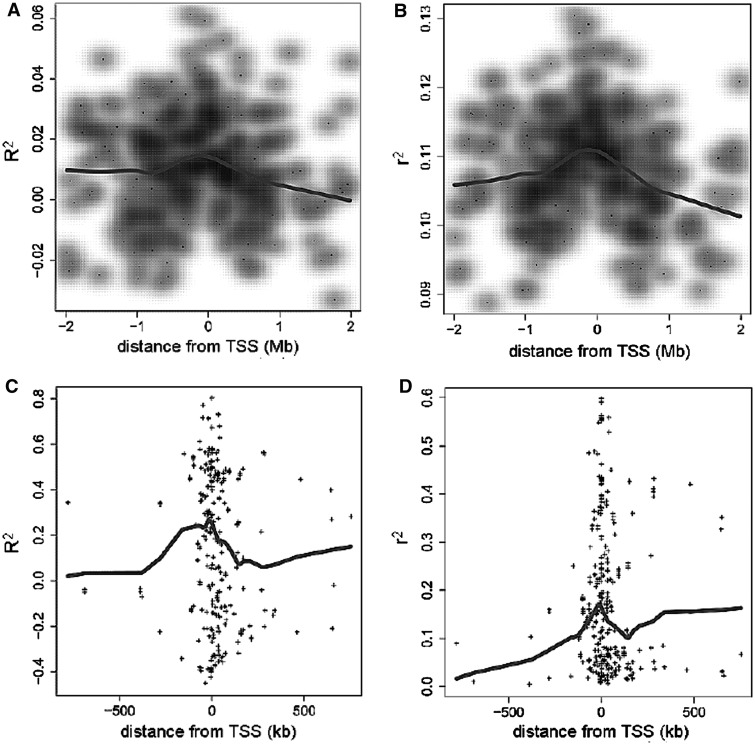

We examined the model fit for each CRE–target gene pair to see how the proportion of expression explained by TFs varies according to the distance between the CRE and the gene’s TSS. In Figure 3, we show that the average proportion of gene expression explained by our regression models, as measured by the  statistic, decreases as we considered CREs positioned further from the TSS. However, we could not detect any significant difference in model fit for CREs within 150 kb of the TSS compared with more distal CREs. For CREs containing eQTL SNPs, the

statistic, decreases as we considered CREs positioned further from the TSS. However, we could not detect any significant difference in model fit for CREs within 150 kb of the TSS compared with more distal CREs. For CREs containing eQTL SNPs, the  statistic also does not differ significantly depending on distance between the CRE and the eQTL’s target gene. Another way to assess co-expression is to assess how well the expression of TFs predicts the expression of target genes. The square of the Pearson correlation between observed and predicted expression also does not seem to be strongly affected by genomic distance. However, a look at expression prediction at a higher resolution (Supplementary Figure S3) reveals that models generated from CREs, which lie within 1 kb of the TSS, explain significantly more expression variation (P < 2.2 × 10−16) than more distal CREs that are beyond 1 kb. The average

statistic also does not differ significantly depending on distance between the CRE and the eQTL’s target gene. Another way to assess co-expression is to assess how well the expression of TFs predicts the expression of target genes. The square of the Pearson correlation between observed and predicted expression also does not seem to be strongly affected by genomic distance. However, a look at expression prediction at a higher resolution (Supplementary Figure S3) reveals that models generated from CREs, which lie within 1 kb of the TSS, explain significantly more expression variation (P < 2.2 × 10−16) than more distal CREs that are beyond 1 kb. The average  for models using CREs that lie within the 1 kb promoter region of target genes is 0.221. Beyond 1 kb, the expression prediction models that are generated from the distal CREs have an average

for models using CREs that lie within the 1 kb promoter region of target genes is 0.221. Beyond 1 kb, the expression prediction models that are generated from the distal CREs have an average  of 0.179. Another interesting feature is that there is also a significant drop in prediction accuracy (P

of 0.179. Another interesting feature is that there is also a significant drop in prediction accuracy (P

) beyond 1 kb even if the CRE is the closest CRE to a target gene (Supplementary Figure S3). Overall, the accuracy of the expression prediction models does not improve even if we choose only the closest CREs. This suggests that sometimes more distal CREs may control gene expression over regulatory elements that are positioned closer to the gene. Consideration of the chromatin structure might clarify the relationship of CREs and regulated genes further.

) beyond 1 kb even if the CRE is the closest CRE to a target gene (Supplementary Figure S3). Overall, the accuracy of the expression prediction models does not improve even if we choose only the closest CREs. This suggests that sometimes more distal CREs may control gene expression over regulatory elements that are positioned closer to the gene. Consideration of the chromatin structure might clarify the relationship of CREs and regulated genes further.

Figure 3.

(A and B)  and

and  of regression models describing co-expression between TFs and all genes relative to distance between CREs and TSS. Hazes indicate a higher density of CREs. (C and D)

of regression models describing co-expression between TFs and all genes relative to distance between CREs and TSS. Hazes indicate a higher density of CREs. (C and D)  and

and  of regression models describing co-expression between TFs and target genes for only CREs with an eQTL SNP. Lines show vertical averaging of the statistics.

of regression models describing co-expression between TFs and target genes for only CREs with an eQTL SNP. Lines show vertical averaging of the statistics.

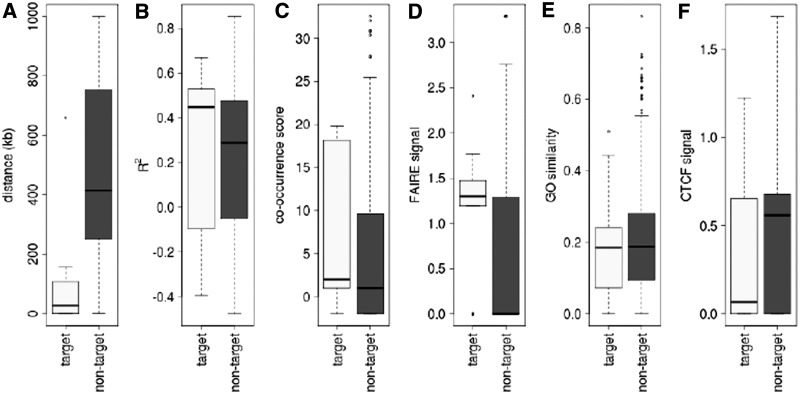

Other weak predictors may help distinguish target genes

Because we believed that gene co-expression is a weak predictor of target genes, we explored other features of genes, which may predict targets better. For each of the 369 CREs that contain eQTL SNPs, we examined all genes within 1 Mb. A gene is considered a target of a CRE if it is significantly associated (P

) with the eQTL SNP located within the CRE. All other genes were classified as non-targets. We identified 20 CREs that are associated with two different target genes, while the rest are each associated with a single target gene. A total of 3638 genes were classified as non-targets, but they are not evenly distributed across CREs, as some CREs are located in gene deserts (Supplementary Figure S4).

) with the eQTL SNP located within the CRE. All other genes were classified as non-targets. We identified 20 CREs that are associated with two different target genes, while the rest are each associated with a single target gene. A total of 3638 genes were classified as non-targets, but they are not evenly distributed across CREs, as some CREs are located in gene deserts (Supplementary Figure S4).

CREs, such as enhancers, can interact with gene promoters by bringing activator proteins to the promoter (3,5); therefore, the likelihood of co-occurrence between TFs bound to the enhancer and TFs bound to the promoter may help determine regulatory potential. We used the ChIP-seq data from the GM12878 cell line to calculate the co-occurrence score for TFs bound at the promoters of each gene, and hypothesized that this feature may help identify genes targeted for regulation. Another feature of gene promoters that may help determine regulatory activity is the presence of open chromatin (9,45). Signal from the FAIRE assay on GM12878 is used to measure open chromatin at each gene’s promoter region. It has been shown that functional similarities between p300 factors and target genes are greater for upregulated genes (19). Therefore, for each of the TFs bound to a CRE, we measured the amount of overlap their GO annotations have with those of target and non-target genes. It has also been shown that CTCF insulator sites block enhancers from interacting with gene promoters (46,47); therefore, we tested to see whether there are more CTCF markers located between CREs and non-target genes than between CREs and targets.

In Figure 4, we compare target and non-target genes in terms of these four features in addition to genomic distance and gene co-expression. Besides genomic distance, we do not see an obvious difference between target and non-target genes based on the features. Nevertheless, we do detect a significantly higher average co-occurrence score and open chromatin signal for target genes (t-test P < 1 × 10−2). There is also a significantly lower signal for CTCF markers between target genes and CREs (t-test P < 1 × 10−6). It is unlikely that each feature by itself would accurately predict target genes, but the slight difference between the two classes of genes can be exploited if we can combine the features to increase their predictive power.

Figure 4.

Features of genes located within 1 Mb of CREs that contain eQTLs. In total, 389 genes are classified as targets of CREs, because they are associated with eQTLs in the CREs. The other 3638 genes are classified as non-targets. We examined six features of genes to see how well they discriminate between targets and non-targets of eQTLs. T-test was used to assess differences between target and non-target genes based on (A) genomic distance between genes and CREs (P < 1 × 10−15), (B) gene co-expression (P = 0.825), (C) TF co-occurrence (target genes have a higher TF co-occurrence score compared with non-targets; P = 8.57 × 10−3), (D) open chromatin signal at the promoter (P = 5.05 × 10−5), (E) TF–gene GO functional similarity (P

) and (F) insulator signal between eQTL and gene (P = 9.83 × 10−7).

) and (F) insulator signal between eQTL and gene (P = 9.83 × 10−7).

Integration of TF and chromatin features accurately predict target genes

Recent advances in ‘ensemble learning’, methods that generate many classifiers and aggregate their results, have resulted in better predictive models. One of these new approaches proposed by Leo Breiman is called random forests (48). The random forests algorithm generates a collection of decision trees, where the node in each tree is split using the best split among a subset of predictors randomly chosen at that node. Each fully grown tree will have a classification for every gene as either target or non-target. The probability of a gene being a target is the ratio of trees that classified the gene as a target. The final prediction of a gene’s class depends on the cutoff we choose for this probability, which we refer to as the target probability cutoff  . The ROC curves allow us to visualize the different sensitivity and specificity measurements achieved at various cutoffs.

. The ROC curves allow us to visualize the different sensitivity and specificity measurements achieved at various cutoffs.

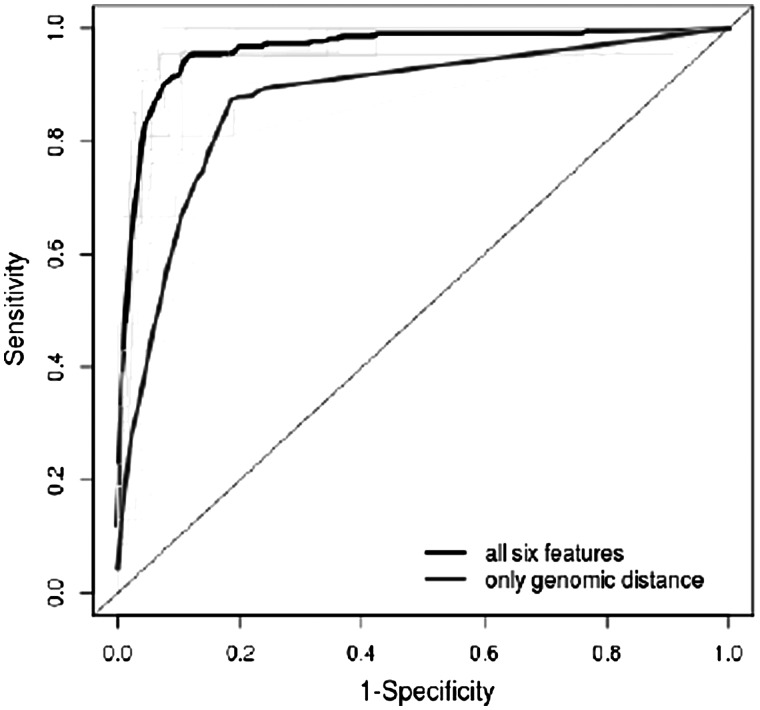

We evaluated prediction of target genes using random forests for 369 CREs that contain eQTL SNPs. The method classified each gene within 1 Mb of a CRE as a target or non-target based on the genomic distance plus five TF and chromatin features that describe the relationship between the gene and the CRE. We compared the predicted target genes with the list of genes associated with eQTL SNPs that are within the CREs. The specificity and sensitivity of the predictions are shown in Figure 5. For  , the classifier achieves 70% sensitivity, 97% specificity and 69% precision for its predictions. Decreasing

, the classifier achieves 70% sensitivity, 97% specificity and 69% precision for its predictions. Decreasing  will allow the classifier to achieve >90% sensitivity while still maintaining 90% specificity. Another measure of prediction performance, which can be used to compare classifiers, is the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The classifier that used all six of the features achieved an AUC of 0.96, while the classifier that used only the genomic distance feature achieved an AUC of 0.90. This may seem like a small decrease in performance for the classifier using only genomic distance, but at

will allow the classifier to achieve >90% sensitivity while still maintaining 90% specificity. Another measure of prediction performance, which can be used to compare classifiers, is the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The classifier that used all six of the features achieved an AUC of 0.96, while the classifier that used only the genomic distance feature achieved an AUC of 0.90. This may seem like a small decrease in performance for the classifier using only genomic distance, but at  , it achieves only 52% sensitivity and 43% precision. The specificity remains high at 93%, as there are many more genes that are non-targets than genes that are targets.

, it achieves only 52% sensitivity and 43% precision. The specificity remains high at 93%, as there are many more genes that are non-targets than genes that are targets.

Figure 5.

Performance of the random forest classifier for predicting target genes of CREs. The average ROC curve for predictions using all six features is higher compared to the ROC curve for predictions using only genomic distance. The ROC curve for each fold of the cross-validation (grey and pale green) is shown. This is also compared with the random prediction of target genes (diagonal line).

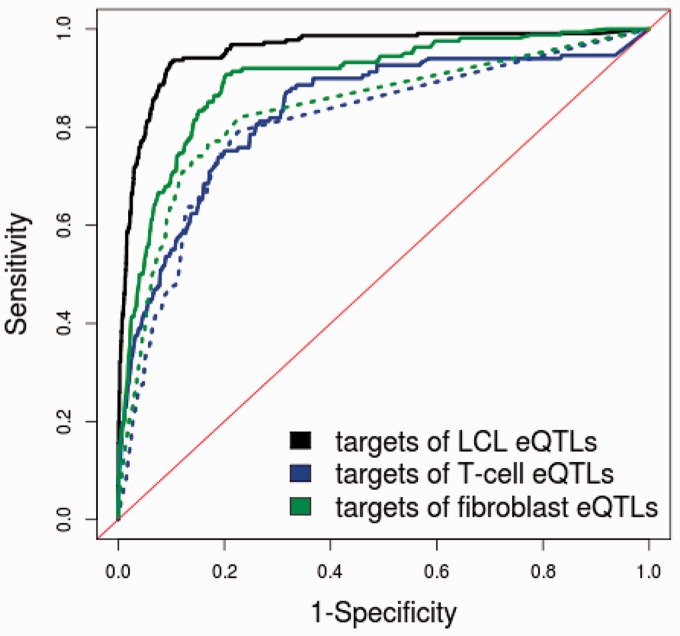

Prediction of eQTL targets in other cell types

To test whether the target gene classifier might be applicable in other cell types, we analyzed eQTL data from T-cells and fibroblasts (30). In total, 9053 eQTL SNPs were identified in the fibroblast cells, and 307 of the CREs identified using ChIP-Seq data from the GM12878 cell were found to co-localize within 100 bases of the eQTL SNPs. Similarly, 8464 eQTL SNPs were identified in T-cells, and 273 CREs were found to co-localize with eQTL SNPs. We trained the classifiers using the LCL data set of 369 CREs and eQTL SNPs, and then predicted target genes of the 307 eQTL SNPs in fibroblasts and 273 eQTL SNPs in T-cells. Forty-three CREs are common between fibroblasts and LCLs, 33 CREs are common between T-cells and LCLs and 14 CREs are common to all three cell types. The classifiers performed less accurately for T-cells (AUC = 0.83) and fibroblasts (AUC = 0.90) compared with the prediction of LCL eQTL targets (Figure 6). This was expected given that the TF and chromatin features were identified using only data from GM12878, a LCL. Despite this, the prediction of fibroblast and T-cell eQTL targets using only genomic distance still had a lower AUC (0.83 and 0.80, respectively) than prediction using all six features. The decrease in prediction accuracy for target genes in fibroblasts and T-cells may be due to the LCL eQTL data used to train the classifier. As shown in Supplementary Figure S10, when we trained the classifier on cell type–specific eQTL data, prediction accuracy improved for T-cells (AUC = 0.95) and fibroblasts (AUC = 0.91).

Figure 6.

Comparison of prediction performance for targets of eQTLs in different cell types. For prediction of fibroblast and T-cell targets, we also trained the classifiers on LCL eQTLs and used features generated from GM12878 ChIP-seq and FAIRE data. Because LCL data were used to train the model, it is not surprising to see that the prediction of targets for LCLs achieved a better ROC curve. The performance of predictions using all six features (solid lines) is compared with the performance of predictions using only genomic distance (dotted line).

We further compared the associations between CREs and target genes in T-cells with chromatin interactions detected by the ChIA-PET assay. CREs that overlap with H3K4me2 regions were identified in CD4+ T-cells. Chromatin interactions detected between these regions and gene promoters were compared with the location of target genes predicted for the CREs (49). Of the 33 CREs that were profiled by ChIA-PET, chromatin interactions are found between 10 CREs and their predicted target genes (Supplementary Table S2). This evidence suggests that our method predicts eQTL–target relationships that are cis-regulatory and may be mediated by chromatin structure.

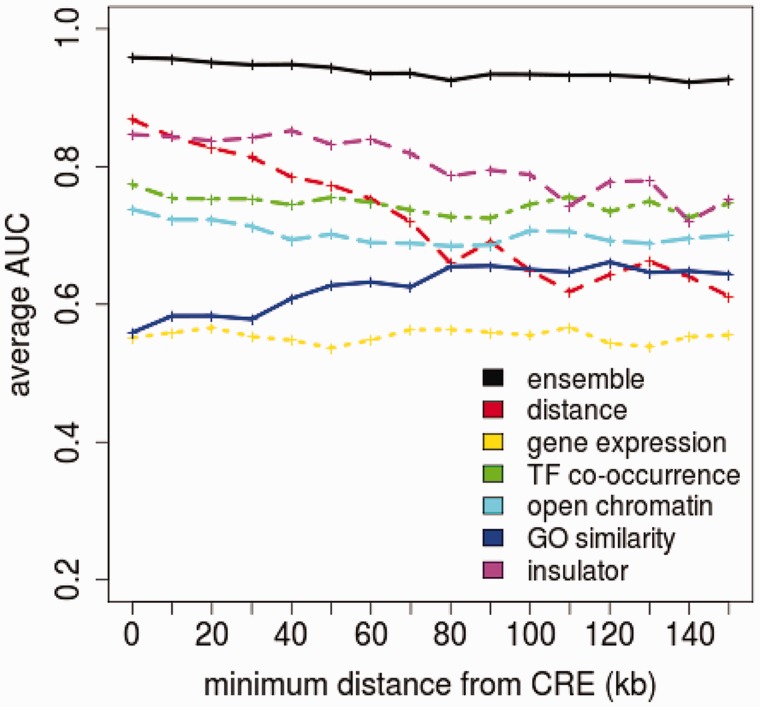

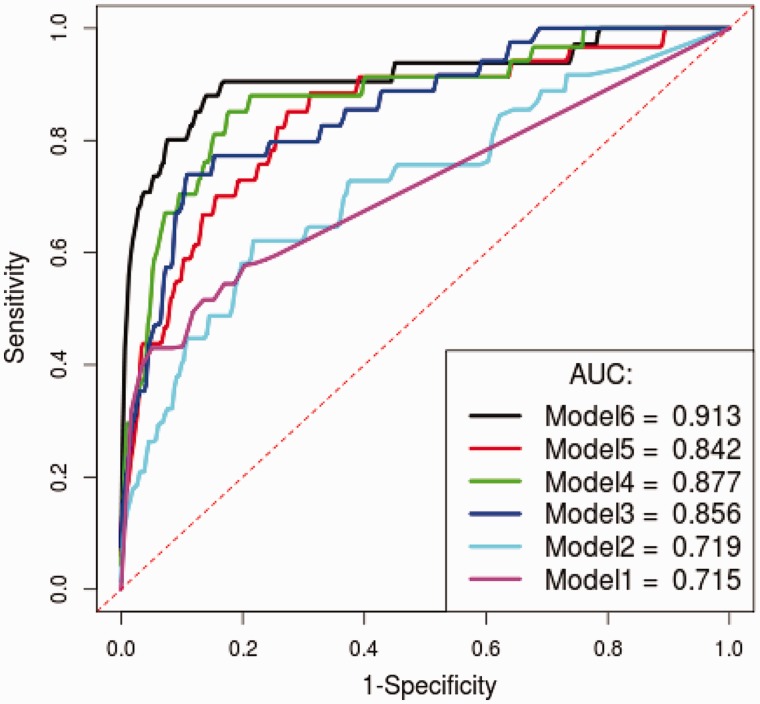

Accuracy of target prediction is robust for distal genes

Combining genomic distance with five TF and chromatin features helped our random forest classifiers achieve a moderate increase in performance compared with using genomic distance alone. As shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S2, the majority of target genes are located in proximity to CREs, whereas non-targets are more uniformly distributed across the genome. This characteristic of target genes allows the classifier to achieve high accuracy using genomic distance alone. The real challenge as mentioned earlier is to accurately predict the few target genes that are distal from CREs and eQTLs. The performance of our random forest classifier using all six features remains high (AUC  ), even for classifying genes located at least 150 kb away from a CRE (Figure 7). In contrast, classification of these distal genes using only genomic distance or any other feature alone achieves an AUC of no greater than 0.75. As shown in Figure 7, the performance of genomic distance as a predictor also drops more than any other predictor for distal genes. At a distance of >150 kb, the presence of insulator markers between the gene and CRE seems to accurately distinguish target genes from non-targets. The feature is able to predict 58% of distal target genes while maintaining >80% specificity (Figure 8). With additional features, we are able to further increase sensitivity without sacrificing much specificity. However, adding the gene co-expression feature actually decreased the performance of a classifier already using four features. This supports the argument that gene co-expression is a weak predictor of target genes.

), even for classifying genes located at least 150 kb away from a CRE (Figure 7). In contrast, classification of these distal genes using only genomic distance or any other feature alone achieves an AUC of no greater than 0.75. As shown in Figure 7, the performance of genomic distance as a predictor also drops more than any other predictor for distal genes. At a distance of >150 kb, the presence of insulator markers between the gene and CRE seems to accurately distinguish target genes from non-targets. The feature is able to predict 58% of distal target genes while maintaining >80% specificity (Figure 8). With additional features, we are able to further increase sensitivity without sacrificing much specificity. However, adding the gene co-expression feature actually decreased the performance of a classifier already using four features. This supports the argument that gene co-expression is a weak predictor of target genes.

Figure 7.

Performance of random forests at classifying genes of a minimum distance away from the CRE. The performance of using all six features (ensemble) is compared with classifiers using only single features.

Figure 8.

Different subgroups of features were tested using the random forest classifier. Distal target genes ( 150 kb from CREs) are predicted using classifiers with increasing number of features: insulators (Model1), insulators + GO similarity (Model2), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin (Model3), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence (Model4), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence + gene co-expression (Model5) and insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence + gene co-expression + genomic distance (Model6).

150 kb from CREs) are predicted using classifiers with increasing number of features: insulators (Model1), insulators + GO similarity (Model2), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin (Model3), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence (Model4), insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence + gene co-expression (Model5) and insulators + GO similarity + open chromatin + TF co-occurrence + gene co-expression + genomic distance (Model6).

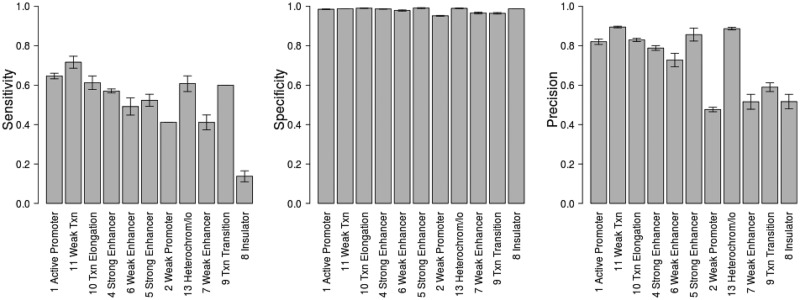

Chromatin state of regulatory elements affects prediction of eQTL targets

At the beginning of our analysis, we noted that CREs may have different functionalities as independently classified by the chromatin signatures at those regions (24). The CREs can therefore be divided into groups based on their chromatin state annotation. Regions of the GM12878 genome classified as strong enhancer or active promoter elements had chromatin markers associated with high levels of gene transcription. The promoter elements were also confirmed by the enrichment of RNAPII-binding sites, and luciferase reporter assays were used to validate the functionality of predicted enhancers. We examined the performance of target gene prediction for each chromatin state group using  . As expected, target prediction for CREs annotated as strong enhancers or active promoters had high sensitivity, specificity and precision (Figure 9). Also as expected, the classifier failed to recall or precisely predict many of the target genes of weak promoters, weak enhancers and insulators. The performance of classifiers seems to reflect the chromatin state predictions of likely and unlikely regulatory elements. Yet, CREs annotated as inactive states of heterochromatin have relatively high target prediction accuracy. The heterochromatin regions, which are characterized by low chromatin marker signal, have been previously found to be associated with a subset of transcribed genes (50). It would be interesting to further investigate the regulatory effect that TF binding has on regions thought to be inactive.

. As expected, target prediction for CREs annotated as strong enhancers or active promoters had high sensitivity, specificity and precision (Figure 9). Also as expected, the classifier failed to recall or precisely predict many of the target genes of weak promoters, weak enhancers and insulators. The performance of classifiers seems to reflect the chromatin state predictions of likely and unlikely regulatory elements. Yet, CREs annotated as inactive states of heterochromatin have relatively high target prediction accuracy. The heterochromatin regions, which are characterized by low chromatin marker signal, have been previously found to be associated with a subset of transcribed genes (50). It would be interesting to further investigate the regulatory effect that TF binding has on regions thought to be inactive.

Figure 9.

CREs have distinct chromatin states based on the histone modification patterns in those regions of the genome. We grouped CREs based on their chromatin state, and examined the performance of predicting eQTL target genes for each group. Genes predicted by random forest at greater than  were classified as targets. Mean values and standard errors after 10-fold cross-validation are shown.

were classified as targets. Mean values and standard errors after 10-fold cross-validation are shown.

Prediction of long-range intra-chromosomal interactions

For longer-range interactions between eQTLs and target genes, the structure of chromosomes may play a role. Regulatory elements may directly interact with distal target genes if the chromosome conformation is such that distant genomic regions are in contact. To identify intra-chromosomal interactions between CREs and predicted target genes in LCLs, we analyzed a HiC data set in the GM06690 cell line (23). In the HiC assay, intra-chromosomal interactions between two loci are estimated by the number of ligation products containing the two loci. A significantly higher (P < 2.2 × 10−16) number of ligation products have loci containing CREs and target genes compared with non-targets (Supplementary Figure S7). Target genes that were predicted by the classifier, but not associated with a eQTL SNP, also had significantly higher (P = 7.23 × 10−7) signal for intra-chromosomal interaction. We further examined how the features used in the random forest classifier relate to the frequency of intra-chromosomal interactions. For each CRE, we examined all genes in the same chromosome and compared their features with the interaction frequency between loci containing the CRE and the genes (Supplementary Figure S8). A total of 143 498 CRE–gene interactions were examined. There seems to be higher interaction frequency when there is higher gene co-expression, TF co-occurrence, open chromatin and insulators between CRE and gene. The relationships are weak, as genic regions only cover a small portion of each chromosome. Also because each ligation product covers approximately 100 kb, the assay does not have good resolution to detect interactions for specific genes. Despite this, we predicted intra-chromosomal interactions using the six CRE–gene features and the random forest classifier trained on HiC data. The predicted interaction frequencies across 10 cross-validations for all CRE-gene pairs achieved an average  of 0.78 when compared with observed interaction frequencies (Supplementary Figure S9). This shows that the features can help predict not only statistical associations between genes and eQTLs but also direct interactions between genomic loci.

of 0.78 when compared with observed interaction frequencies (Supplementary Figure S9). This shows that the features can help predict not only statistical associations between genes and eQTLs but also direct interactions between genomic loci.

DISCUSSION

The influx in data on gene regulators has enabled researchers to identify regulatory elements by examining histone modification markers and TF-binding hot spots (25,40). Previous studies have also shown that detection of co-localization sites between chromatin features and genetic variants in humans is useful for identifying regulatory elements (24,51). They postulated that the SNPs that influence gene expression may also affect the local chromatin structure. For instance, Degner et al. (51) defined dsQTLs as loci with SNPs significantly correlated with DNase I sensitivity sites. Fifty-five percent of the detected dsQTLs are also eQTLs in LCLs, suggesting that genetic variation may influence both chromatin accessibility and phenotypic variation. The enrichment of TF-binding sites in those dsQTLs suggested possible mechanisms for the elements to act as repressors or enhancers (51), whereas the presence of CTCF insulator elements between the dsQTL and the gene’s TSS was observed to reduce the probability that a dsQTL is an eQTL. This is consistent with observations that CTCF insulators block interactions between regulatory elements and genes (46,47). The analysis of dsQTL and eQTL interactions with genes was restricted to only the closest genes, and knowledge about long-range interactions is still limited.

Because the majority of identified interactions with eQTLs are with nearby genes, most studies ignore long-range interactions. Gene regulatory networks based on co-expression could be used to identify relationships between the TFs bound to eQTL regions and target genes, but inference of the networks is difficult for combinatorial regulation involving many TFs (52). Rdelsperger et al. (19) suggested using evidence of protein–protein interactions between enhancer TFs and TFs binding to the gene’s promoter to identify targets. We considered including protein–protein interactions as a feature, but 11 of the 29 TFs that were profiled did not have any experimental evidence of physical interactions according to the STRING database (53). Instead, we used functional similarity and co-occurrence of TFs as proxies for physical interaction. Detection of shared functional similarity through GO terms is able to recover as much as 88% of known protein–protein interactions across multiple species and identify novel interactions in humans (54,55). Although co-occurrence of TFs has been shown to be a good predictor of protein–protein interactions in yeast (56), until now, there was not enough data on TF-binding sites in humans to exploit this feature.

We are able to use the random forest classifier to integrate the different TF and chromatin features without introducing a complex parametric model. Using multiple features not only allows us to predict 70% of the genes associated with genetic variants, but also we have the possibility of identifying novel gene regulatory interactions. This is especially useful when most eQTL data in human LCLs are underpowered for identifying the genetic pathways involved in complex traits (57). For the purposes of this study, we only examined CREs co-localized with eQTLs, but there are thousands of other CREs without eQTLs that can associated with genes using our classifier. It is also important to note that the CRE–target gene associations provided by the eQTL data are based on correlations and may describe some indirect regulatory interactions (58). The random forest classifier, which is trained on eQTL data, may not be predicting only direct targets of CREs, but it also does help identify TF and chromatin signals that link non-coding SNPs to nearby genes. Without better experimental evidence of direct regulatory relationships, we are limited when validating our predictions. Our hope is that new experimental approaches, such as chromatin interaction analysis by paired-end tag sequencing (ChIA-PET), can one day be conducted in a high-throughput manner to validate interactions between promoters and enhancers (49). Our results also show that the quality of these features for inference is limited by cell specificity. This represents a limitation in our method, where features detected in the GM12878 cell type were not as useful for predicting target genes of eQTLs in fibroblasts and T-cells. The dynamic nature of TF occupancy results in dramatically different TF-binding site profiles detected across different cell types (7,59), and in turn causes differential gene expression.

For each gene, the random forest classifier outputs the ratio of trees in the forest voting for the target classification. This ratio could represent a prioritized list of candidate CRE–target gene interactions to be validated experimentally. Alternatively, we could predict a target by selecting the gene within 1 Mb of a CRE that has the highest ratio. This would make target gene predictions more precise, but we would also have to make the assumption that each element can only regulate one target gene. Making such a strong assumption would hinder the possibility of discovering novel targets. To gain further insight into gene regulatory mechanisms, we could examine the measures for variable importance returned by the classifier (48). However, correlations between TF-binding sites and chromatin markers mean that multicollinearity exists in models combining multiple features (43). This does not reduce the predictive power of the random forest classifier, but makes it difficult to evaluate the contribution of individual features toward the prediction of target genes. To account for correlations between predictor variable when assessing their relative importance, we can permute the values of each feature in the random forests while conditioning on the other features (60). When we did this, we found that the genomic distance feature has the highest conditional importance score, which is consistent with empirical results showing that it is the best predictor of gene–eQTL associations. The ranking of features based on importance scores, shown in Supplementary Figure S5, further suggests that the insulator, TF co-occurrence and GO similarity have some impact on the prediction of target genes, especially for those that are distal (Figure 7). Finding a reduced model based on these features may allow us to identify specific factors influencing long-range regulatory interactions. This will be especially important when more experimental data sets become publicly available, increasing the number of features to consider for integrative analysis.

In summary, we have examined TF and chromatin features that co-localize along the genome. Specifically, we proposed using genomic distance, gene co-expression, open chromatin, TF co-occurrence, GO similarity and insulator marks as possible features for predicting genes associated with eQTLs. Although all the features are weak predictors for distal genes, we have shown that an ensemble of these features can significantly improve eQTL target prediction. It is, however, crucial for these features to be obtained from the same cell population, owing to the cell type specificity of these features. Through this approach, we can propose mechanistic explanations for how genetic variants influence target genes through chromatin state and TF binding dynamics.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Figures 1–10 and Supplementary Dataset 1.

FUNDING

European Commission Marie Curie Actions FP7 (to D.W. and L.W.); British Heart Foundation (to A.R.); NIHR Programme (to A.R.); Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada Postgraduate Scholarship (to D.W.). Funding for open access charge: Medical Research Council.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the ENCODE consortium for making their data freely available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Segal E, Widom J. From DNA sequence to transcriptional behaviour: a quantitative approach. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:443–456. doi: 10.1038/nrg2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine M, Davidson EH. Gene regulatory networks for development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4936–4942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408031102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenborn JR, Dorschner MO, Sekimata M, Santer DM, Shnyreva M, Fitzpatrick DR, Stamatoyonnapoulos JA, Wilson CB. Comprehensive epigenetic profiling identifies multiple distal regulatory elements directing transcription of the gene encoding interferon-γ. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:732–742. doi: 10.1038/ni1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon H, Boss JM. PU.1 binds to a distal regulatory element that is necessary for B cell-specific expression of CIITA. J. Immunol. 2010;184:5018–5028. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolis IK, McKay DJ, Mantouvalou E, Lomvardas S, Merika M, Thanos D. Transcription factors mediate long-range enhancerpromoter interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20222–20227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902454106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consortium TEP. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consortium TEP. A user’s guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee B, Bhinge AA, Battenhouse A, McDaniell RM, Liu Z, Song L, Ni Y, Birney E, Lieb JD, Furey TS, et al. Cell-type specific and combinatorial usage of diverse transcription factors revealed by genome-wide binding studies in multiple human cells. Genome Res. 2012;22:9–24. doi: 10.1101/gr.127597.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song L, Zhang Z, Grasfeder LL, Boyle AP, Giresi PG, Lee B, Sheffield NC, Grf S, Huss M, Keefe D, et al. Open chromatin defined by DNaseI and FAIRE identifies regulatory elements that shape cell-type identity. Genome Res. 2011;21:1757–1767. doi: 10.1101/gr.121541.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rye M, Strom P, Hndstad T, Drabls F. Clustered ChIP-Seq-defined transcription factor binding sites and histone modifications map distinct classes of regulatory elements. BMC Biol. 2011;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narlikar L, Sakabe NJ, Blanski AA, Arimura FE, Westlund JM, Nobrega MA, Ovcharenko I. Genome-wide discovery of human heart enhancers. Genome Res. 2010;20:381–392. doi: 10.1101/gr.098657.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Y, Yao Z, Sarkar D, Lawrence M, Sanchez GJ, Parker MH, MacQuarrie KL, Davison J, Morgan MT, Ruzzo WL, et al. Genome-wide MyoD binding in skeletal muscle cells: a potential for broad cellular reprogramming. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Q, Bardet AF, Patton B, Purvis J, Johnston J, Paulson A, Gogol M, Stark A, Zeitlinger J. High conservation of transcription factor binding and evidence for combinatorial regulation across six Drosophila species. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:414–420. doi: 10.1038/ng.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh Y, Wu Q, Chew J, Vega VB, Zhang W, Chen X, Bourque G, George J, Leong B, Liu J, et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagai T, Amano T, Tamura M, Mizushina Y, Sumiyama K, Shiroishi T. A cluster of three long-range enhancers directs regional Shh expression in the epithelial linings. Development. 2009;136:1665–1674. doi: 10.1242/dev.032714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotelo J, Esposito D, Duhagon MA, Banfield K, Mehalko J, Liao H, Stephens RM, Harris TJR, Munroe DJ, Wu X. Long-range enhancers on 8q24 regulate C-Myc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:3001–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906067107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahituv N, Prabhakar S, Poulin F, Rubin EM, Couronne O. Mapping cis-regulatory domains in the human genome using multi-species conservation of synteny. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:3057–3063. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kikuta H, Laplante M, Navratilova P, Komisarczuk AZ, Engstrm PG, Fredman D, Akalin A, Caccamo M, Sealy I, Howe K, et al. Genomic regulatory blocks encompass multiple neighboring genes and maintain conserved synteny in vertebrates. Genome Res. 2007;17:545–555. doi: 10.1101/gr.6086307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rdelsperger C, Guo G, Kolanczyk M, Pletschacher A, Khler S, Bauer S, Schulz MH, Robinson PN. Integrative analysis of genomic, functional and protein interaction data predicts long-range enhancer-target gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2492–2502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He A, Kong SW, Ma Q, Pu WT. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5632–5637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visel A, Blow MJ, Li Z, Zhang T, Akiyama JA, Holt A, Plajzer-Frick I, Shoukry M, Wright C, Chen F, et al. ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature. 2009;457:854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature07730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman-Aiden E, Van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Calcar SV, Qu C, Ching KA, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, Pharoah PDP, Thompson D, Ballinger DG, Struewing JP, Morrison J, Field H, Luben R, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 2007;447:1087–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature05887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakabe NJ, Savic D, Nobrega MA. Transcriptional enhancers in development and disease. Genome Biol. 2012;13:238. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-1-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Yang X, Lum PY, Kasarskis A, Zhang B, Wang S, Suver C, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. PMID: 18462017, PMCID: PMC2365981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery SB, Sammeth M, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Lach RP, Ingle C, Nisbett J, Guigo R, Dermitzakis ET. Transcriptome genetics using second generation sequencing in a Caucasian population. Nature. 2010;464:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nature08903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimas AS, Deutsch S, Stranger BE, Montgomery SB, Borel C, Attar-Cohen H, Ingle C, Beazley C, Arcelus MG, Sekowska M, et al. Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell typedependent manner. Science. 2009;325:1246–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1174148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pastinen T. Genome-wide allele-specific analysis: insights into regulatory variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nrg2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S, Dudley AM, Drubin D, Silver PA, Krogan NJ, Pe’er D, Koller D. Learning a prior on regulatory potential from eQTL data. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaffney D, Veyrieras J, Degner JF, Pique-Regi R, Pai AA, Crawford GE, Stephens M, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Dissecting the regulatory architecture of gene expression QTLs. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozowsky J, Euskirchen G, Auerbach RK, Zhang ZD, Gibson T, Bjornson R, Carriero N, Snyder M, Gerstein MB. PeakSeq enables systematic scoring of ChIP-seq experiments relative to controls. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:66–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle AP, Guinney J, Crawford GE, Furey TS. F-Seq: a feature density estimator for high-throughput sequence tags. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2537–2538. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novershtern N, Subramanian A, Lawton LN, Mak RH, Haining WN, McConkey ME, Habib N, Yosef N, Chang CY, Shay T, et al. Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell. 2011;144:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, De Bakker PIW. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized Additive Models. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlicker A, Domingues FS, Rahnenfhrer J, Lengauer T. A new measure for functional similarity of gene products based on Gene Ontology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moorman C, Sun LV, Wang J, De Wit E, Talhout W, Ward LD, Greil F, Lu X, White KP, Bussemaker HJ, et al. Hotspots of transcription factor colocalization in the genome of drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12027–12032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bar-Joseph Z, Gerber GK, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Yoo JY, Robert F, Gordon DB, Fraenkel E, Jaakkola TS, Young RA, et al. Computational discovery of gene modules and regulatory networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1337–1342. doi: 10.1038/nbt890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouyang Z, Zhou Q, Wong WH. ChIP-Seq of transcription factors predicts absolute and differential gene expression in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21521–21526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904863106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Rendon A, Ouwehand W, Wernisch L. Transcription factor co-localization patterns affect human cell type-specific gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaulton KJ, Nammo T, Pasquali L, Simon JM, Giresi PG, Fogarty MP, Panhuis TM, Mieczkowski P, Secchi A, Bosco D, et al. A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:255–259. doi: 10.1038/ng.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuddapah S, Jothi R, Schones DE, Roh T, Cui K, Zhao K. Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 2009;19:24–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.082800.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, Zhang MQ, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chepelev I, Wei G, Wangsa D, Tang Q, Zhao K. Characterization of genome-wide enhancer-promoter interactions reveals co-expression of interacting genes and modes of higher order chromatin organization. Cell Res. 2012;22:490–503. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grewal SIS, Jia S. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:35–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Degner JF, Pai AA, Pique-Regi R, Veyrieras J, Gaffney DJ, Pickrell JK, Leon SD, Michelini K, Lewellen N, Crawford GE, et al. DNase[thinsp]I sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature. 2012;482:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marbach D, Prill RJ, Schaffter T, Mattiussi C, Floreano D, Stolovitzky G. Revealing strengths and weaknesses of methods for gene network inference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6286–6291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913357107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maetschke SR, Simonsen M, Davis MJ, Ragan MA. Gene ontology-driven inference of proteinprotein interactions using inducers. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:69–75. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He M, Wang Y, Li W. PPI finder: a mining tool for human protein-protein interactions. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manke T, Bringas R, Vingron M. Correlating protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction networks. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]