Abstract

More than a decade ago, the purification of the form of the RNA polymerase II (PolII) engaged in elongation led to the discovery of an associated, multi-subunit (Elp1-6) complex named “Elongator” by the Svejstrup lab. Although further evidence supported the original notion that Elongator is involved in transcription, Elongator lacked some of the expected features for a regulator of the elongating PolII. The discovery by the Byström lab, based on genetic dissection, that Elongator is pivotal for tRNA modifications, and that all the reported phenotypes of Elongator mutants are suppressed by the overexpression of two tRNAs added to the confusion. The increasing range of both potential substrates and biological processes regulated by Elongator in higher eukaryotes indicates that the major challenge of the field is to determine the biologically relevant function of Elongator. Our recent proteome-wide study in fission yeast supports a coordinated codon-dependent regulation of translation by Elongator. Here we provide additional analyses extending this hypothesis to budding yeast and worm.

Keywords: translation, codon, elongator, tubulin, proteome

Elongator, an RNA Polymerase II-Associated Histone Acetyltransferase … and More

While most DNA-binding proteins will dissociate from DNA at about 300 nM salt concentration, the elongating yeast RNA polymerase II is stable at much higher concentrations. This feature constituted the basis of Elongator isolation. Purified Elongator from yeast or human cells acetylates histone H3 primarily, and the inactivation of Elongator results in a decreased acetylation in vivo.1-3 Also, a marked synthetic growth defect is observed when mutants in Elongator and Gcn5, the SAGA-associated histone acetyltransferase, are combined, which is correlated with a decrease in acetylation and transcription.4 Therefore, an extensive biochemical dissection, together with a simple but convincing phenotypic analysis, provided a wealth of support for a model where Elongator regulates transcription through associated histone acetylation.

Based on the above model, Elongator was expected to be chromatin-associated and mainly nuclear, but both predictions turned out incorrect: Elongator could not coimmunoiprecipitate chromatin, and the complex was shown to be mainly cytoplasmic by the Young lab.5 The failure to ChIP Elongator was nuanced by a subsequent study showing it had a more pronounced affinity for RNA than DNA and indeed was associated with the nascent RNA emanating from PolII.6 The subcellular localization was rather supportive of a second distinct function reported for Elongator in the polarized transport of vesicles during exocytosis.7

The discovery that the ELP1-ELP6 genes were required for an early step in the synthesis of the 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl (mcm5) modifications of the position 5 in the wobble uridines of tRNAs and the direct association of Elongator with the tRNA susceptible to formation of these modifications supported yet an additional function for the complex.8 In addition, it also provided an alternative explanation for the much greater affinity of Elongator for RNA rather than DNA (see above).

Familial dysautonomia (FD) is a disease of the autonomic and sensory nervous system resulting from mutations in Elongator. Target genes were identified using RNA interference (RNAi) and fibroblasts from FD patients. These genes displayed histone H3 hypoacetylation and progressively lower RNAPII density through the coding region in FD cells.9 Several target genes encode proteins implicated in cell motility. It was suggested that defects in tubulin acetylation and impairment in microtubule-based trafficking was the underlying cause of the disease.10 A subsequent study supported this hypothesis by showing that a defect in the migration of cortical neurons and a reduction in the acetylation of α-tubulin are hallmarks of Elongator inactivation.11

Next, Elongator was linked to yet another pathway, when a short-interfering, RNA-mediated knockdown in mouse zygotes identified Elp3 as a required factor for paternal DNA demethylation.12

Altogether, this amazingly dispersed set of functions and substrates led to the intriguing, and somewhat unlikely, suggestion that Elongator is a multitasking complex controlling a broad range of processes through acetylation of various substrates.

Elevated Levels of Two tRNAs Bypass All the In Vivo Requirements of Elongator in Transcription and Exocytocis

A report by the Byström team in 2006 demonstrated that the overexpression of tRNALysUUU, (a lysine tRNA whose anticodon is UUU) and tRNAGluUUC (a glutamine tRNA whose anticodon is UUG) was sufficient to suppress all the phenotypes resulting from Elongator inactivation in yeast but not the tRNA modification defect itself.13 This work is remarkable both because of the simplicity of the experiment and its unusual reach.

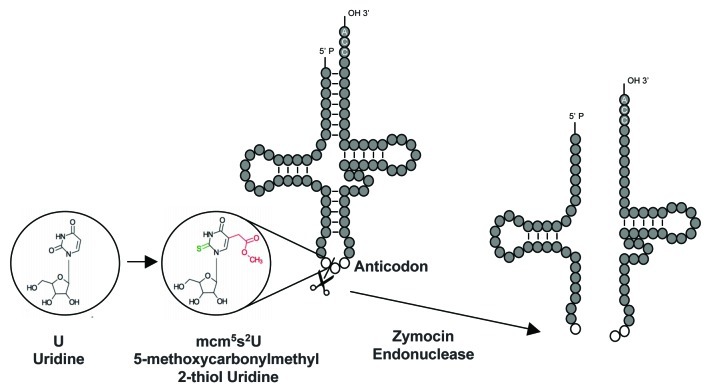

tRNAs from all organisms contain modified nucleosides, and a uridine present in the wobble position (U34) is almost universally modified.14-16 Particularly, the tRNALysUUU, tRNAGluUUC and tRNAGlnUUG, are doubly modified with the addition of a thiol (s2) at the 2-carbon and a methoxy-carbonyl-methyl group (mcm5) at the 5-carbon on the uridine (Fig. 1). The complex double-modification (mcm5s2U34) is required to offset the translational inefficiency of the AA-ending codons.17-19 The complete thiolation pathway is described,20-22 and as mentioned above, the Elongator complex is pivotal for the synthesis of the mcm5 moiety, although the pathway is not elucidated. The involvement of Elongator in tRNA modification is also supported by the originally puzzling resistance of any Elongator mutant to the Zymocin toxin (Fig. 1). The discovery that Zymocin cleaves tRNAs only when they bear the double mcm5s2 modification provided a very convincing molecular explanation for the resistance.8,23

Figure 1. Wobble uridines bearing the double-modification mcm5s2 are recognized by the Zymocin endonuclease. tRNAs reading codons belonging to split codon boxes, which include the tRNALysUUU, tRNAGluUUC and tRNAGlnUUG, are thiolated (s2) at the 2-carbon and contain a methoxy-carbonyl-methyl modification (mcm5) at the 5-carbon on the uridine. The double modification is a prerequisite for the action of the zymocin endonuclease that cleaves the anticodon loop. The action of the zymocin is indicated by a scissor, and the target uridine (unmodified or modified) is highlighted.

Another important aspect of the Esberg et al. work is the fact that all the phenotypes described for the budding yeast elongator mutant can be reconstituted by inactivation of ncs2, a gene implicated in the thiolation (s2) of tRNAs. The fact that Ncs2 affects tRNA modification by an Elongator-independent mechanism and yet both ncs2 and elp mutants display identical phenotypes that can also be suppressed by the increased level of tRNALysUUU and tRNAGluUUC is a strong genetic argument supporting that the prevalent role of Elongator is in tRNA modification.

The recent report of the crystal structure of the yeast subcomplex of Elongator proteins 4, 5 and 6 showed that each subunits adopt almost identical RecA folds to form a heterohexameric ring-like structure resembling the hexameric RecA-like ATPases. This study also demonstrated the specific binding of the hexameric Elp456 subcomplex to tRNAs in a manner regulated by ATP, supporting a role of Elongator in tRNA modification.24

Contrary to a transcription defect that can be easily assessed by high-throughput technologies, the emerging question of Elongator targets, affected at the translation level, is far from trivial. Recently, our lab used an original proteome-wide approach based on reverse protein arrays to address this question in the fission yeast. This work revealed that the inactivation of elp3 (encoding a subunit of Elongator) or ctu1 (encoding the tRNA wobble uridine thiolase) similarly affected the fission yeast proteome. The study also revealed that a codon-dependent control of gene expression, mostly through an increased usage of the lysine AAA codon, applies to groups of functionally related genes rather than single genes.25-27 To us, this aspect is essential, as the coordinated expression of functionally related groups of genes is an universal feature of living cells.

Four recently published papers allowed us to further test the possibility of tRNA modification-dependent coordination of gene expression.

Translational Control of Telomeric Gene Silencing and DNA Damage Response

The Stillman group reported that a budding yeast Elongator mutant partially loses silencing of telomeric genes and is sensitive to both a DNA replication inhibitor (HU, hydroxyurea) and a DNA-damage agent (MMS, methanesulfonate). They suggested that hypoacetylation of histones in the absence of Elongator affected the integrity of telomeric chromatin.28 Using an identical rationale and set up to what was described in the Esberg et al. paper, the Byström lab convincingly reported that the silencing defect and the sensitivity to drugs were a direct consequence of Elongator’s role in tRNA modification. Importantly, they showed that the expression level of the Sir4 protein, a key player in the assembly of silent chromatin at telomeres, was reduced in the Elongator mutant.29

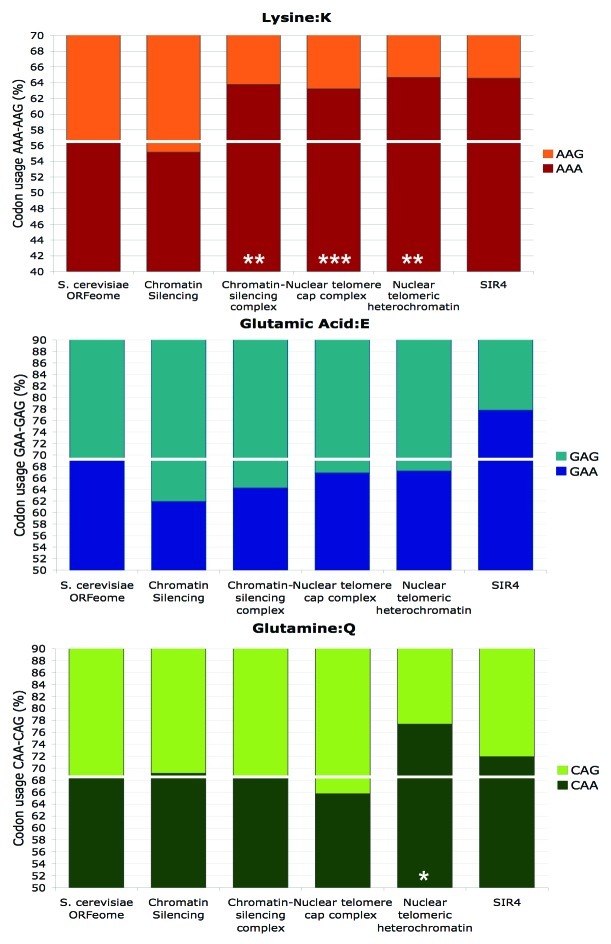

In order to test the validity of the coordinated regulation model, we have analyzed the codon content of Sir4, which revealed enrichment in the -AA codons (Fig. 2). Moreover, codon content analysis showed that the gene ontology groups encompassing telomeric gene silencing were statistically enriched for the AAA codon (Fig. 2). This behavior is very reminiscent of our observations in fission yeast, where functional groups related to the phenotypes of an Elongator mutant were also enriched for the AAA codon. A proteome-wide approach would be very informative to confirm the prediction that codon content-dependent regulation by Elongator occurs at the level of functional groups.

Figure 2. Functional groups of genes related to SIR4 and telomeric silencing are enriched in AAA lysine codon in budding yeast. Codon usage for lysine (AAA-AAG), glutamic acid (GAA-GAG) and glutamine (CAA-CAG) within the budding yeast SIR4 gene (YDR227W) and the gene ontology groups (chromatin silencing GO:0006342 n = 9; chromatin-silencing complex GO:0005677 n = 5; nuclear telomere cap complex GO:0000783 n = 9; nuclear telomeric heterochromatin GO:0005724 n = 6) it belongs to, according to the SGD (Saccharomyces Genome Database, www.yeastgenome.org). The ORFeome codon usage is indicated by the white line. Note that the y-axis, representing the codon usage of 100% of the indicated amino acids, is truncated to highlight deviations from the ORFeome codon usage. (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.)

The Case of α-Tubulin Acetylation

Acetylation of α-tubulin is a posttranslational modification found inside the microtubule lumen and required to anchor some molecular motors. The Elongator complex was shown to be a molecular determinant of tubulin acetylation and consequent radial migration of projection neurons. Moreover, an α-tubulin mutant that cannot be acetylated (K40A) recapitulated the migratory defects observed when Elongator is inactivated.11 Because a purified Elp3-enriched fraction promotes tubulin acetylation in vitro, Elongator was hypothesized to be the genuine tubulin acetylase. This possibility was later tested in the nematode C. elegans by the Byström and the Cassata labs that reached contradictory conclusions. The Byström team reported that Elongator inactivation led to a defect in salt chemotaxis learning, which was likely a consequence of a decreased expression of neuropeptide and defective accumulation of the acetylcholine neurotransmitter at the synapsis. The absence of Elongator abrogated the synthesis of the mcm5 moiety of the wobble uridine modification, resulting in translational defects. The resulting phenotypes were aggravated by the inactivation of tut-1 (the ortholog of budding yeast TUC1 and fission yeast ctu1), which encodes the wobble uridine thiolase. No reduction in α-tubulin acetylation was noted, which uncoupled the neurological defects from the proposed role of Elongator in neuronal α-tubulin acetylation.30 In contrast, the Cassata laboratory reported that the acetylatransferase activity of Elongator was required for α-tubulin acetylation, microtubule-associated vesicles dynamics and as a consequence of neuronal development.31 The reduction of α-tubulin acetylation was apparent during embryogenesis and to some extent at several larval stages, but not in the adult, which may explain the discrepancy between both studies as the Chen et al. paper only analyzed acetylated α-tubulin level in adult worms. In conclusion, both studies agreed on the fact that Elongator mutants displayed defects in neurotransmitter levels, but not on the molecular origin of this defect.

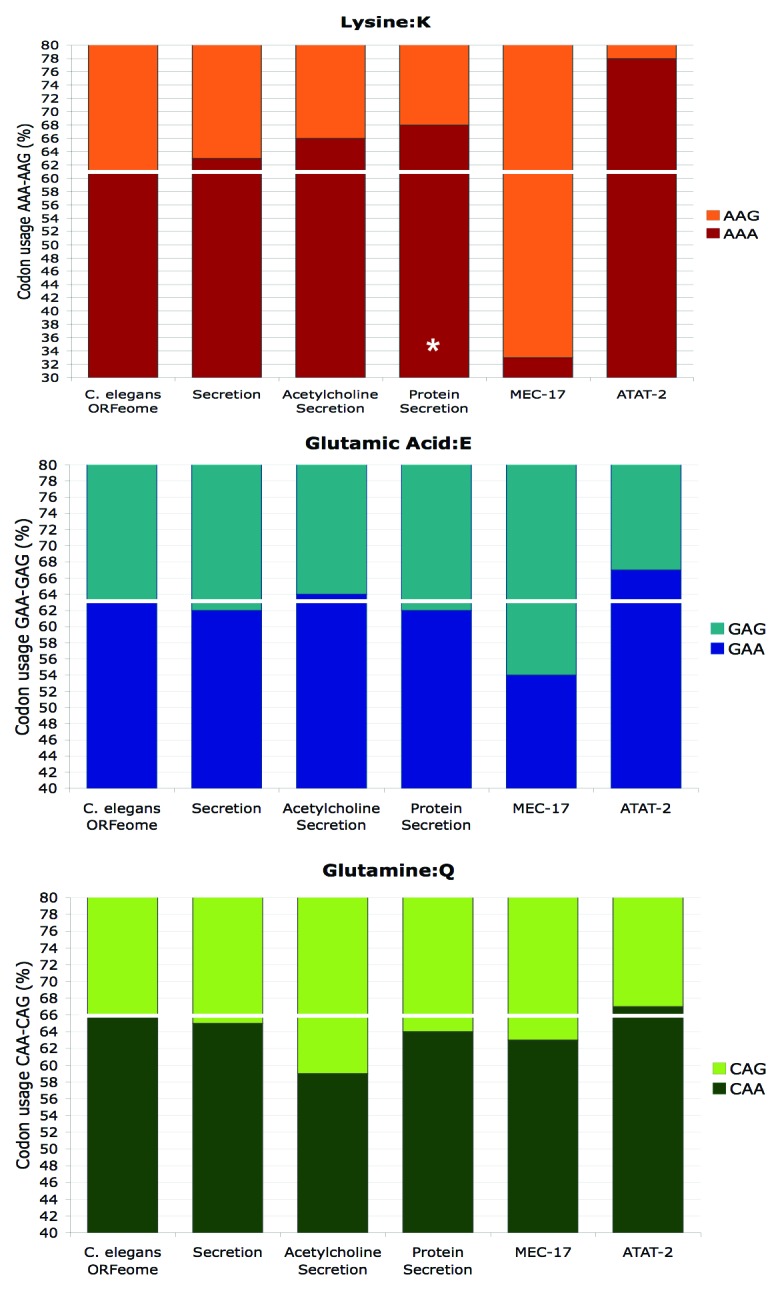

An important step in resolving this issue was the identification by two research groups of Mec-17 as the genuine α-tubulin acetyltransferase in the nematode, Tetrahymena, zebrafish and mammalian cells.32,33 The converging set of evidences that was recently strengthened34,35 strongly supports that Elongator is not a direct tubulin acetytransferase in these model species. In C. elegans, the mec-17 gene exists together with the atat-2 paralog, and it was concluded that they redundantly function in acetylating the lysine 40 in α-tubulin (encoded by mec-12). Although in the double-mutant acetylated α-tubulin is indeed not detectable, both of the single mutants show a reduced level when analyzed on a synchronized population, which argues against a full redundancy.33 We analyzed the codon content of the two paralogs and found a strong opposite bias for the lysine codon usage between mec-17 (33% AAA/67% AAG) and atat-2 (78% AAA/22% AAG) while the average lysine codon usage is 61% AAA/39% AAG in C. elegans (Fig. 3). Based on this unexpected finding, we speculate that Elongator may regulate the expression level of Atat-2 through its elevated AAA codon content and tRNA modification. A developmental regulation of this process would explain why Elongator mutants display an α-tubulin acetylation defect only at an early stage and not in the adulthood. Another striking feature of our codon content analysis is that the C. elegans functional category encompassing acetylcholine secretion also shows an enrichment for the AAA condon, again suggesting a coordinated regulation of gene expression. Further experimental work is needed to explore these possibilities.

Figure 3. The C. elegans mec-17 and ata-2 tubulin acetyltransferase coding regions have opposite strongly skewed AAA codon usage. Codon usage for lysine (AAA-AAG), glutamic acid (GAA-GAG) and glutamine (CAA-CAG) within the C. elegans atat-2 (W06B11.1) and mec17 (F57H12.7) genes and the Gene Ontology groups related to protein secretion (secretion GO:0046903 n = 91; acetylcholine secretion GO:0014055 n = 5; protein secretion GO:0009306 n = 17). The ORFeome codon usage is indicated by the white line. Note that the y-axis, representing the codon usage of 100% of the indicated amino acids, is truncated to highlight deviations from the ORFeome codon usage. (* p < 0.05.)

Considering the reported requirement of Elongator in neurological processes in higher eucaryotes, the α-tubulin acetyltransferase could be the first conserved target under translational control by Elongator. There is no convincing evidence of α-tubulin aceltylation in yeast.36-38 An ortholog of the mec-17 gene is not found in either the S. cerevisiae or the S. pombe genome, and the target lysine is conserved in S. cerevisiae but not in S. pombe (data not shown).

Conclusion and Future Directions

The Elongator complex provides a remarkable synthesis of all the difficulties and traps in the identification of the biologically relevant role and the molecular function of a protein or a complex. It is uncertain whether the complex in metazoans functions directly in a broad variety of processes or rather acts though a small number, or even a single target, which reverberates on pleiotropic effects. The availability of the TUC1/ctu1 thiolase mutant that affects the second moiety of the mcm5s2 modification independently of Elongator constitutes a powerful lever to test the relevance of tRNA modification in any new phenotype attributed to Elongator.

Extensive work in budding yeast and fission yeast strongly support that Elongator is primarily implicated in tRNA modifications in these two species, which underlies a new mechanism that fundamentally contributes to gene expression regulation.

By an unexpected twist of scientific endeavor, the name Elongator is still actually well-suited, as the complex, most likely, is critical for efficient elongation during translation of some mRNAs harboring skewed codon content.

Materials and Methods

The Gene Ontology groups were defined using the AMIGO (www.amigo.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/amigo/term_enrichment), GO-miner (www.discover.nci.nih.gov/gominer/index.jsp) and GOEAST (www.omicslab.genetics.ac.cn/GOEAST/) software toolkit according to the developer instructions.39 The Codon usage was obtained from the Codon Usage Database (www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/) and computed with the EMBOSS cusp (www.emboss.sourceforge.net/apps/cvs/emboss/apps/cusp.html). Statistical analyses were performed using a Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism 4) and the associated p values defined as: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank the GEMO laboratory for discussions. This work was supported by grants FRFC 2.4510.10, Credit aux chercheurs 1.5.013.09 and MIS F.4523.11 to D.H. F.B. is a FRIA Research Fellow. D.H. is a FNRS Research Associate.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/22689

References

- 1.Otero G, Fellows J, Li Y, de Bizemont T, Dirac AM, Gustafsson CM, et al. Elongator, a multisubunit component of a novel RNA polymerase II holoenzyme for transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 1999;3:109–18. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkler GS, Kristjuhan A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Svejstrup JQ. Elongator is a histone H3 and H4 acetyltransferase important for normal histone acetylation levels in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022042899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittschieben BO, Otero G, de Bizemont T, Fellows J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ohba R, et al. A novel histone acetyltransferase is an integral subunit of elongating RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell. 1999;4:123–8. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80194-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittschieben BO, Fellows J, Du W, Stillman DJ, Svejstrup JQ. Overlapping roles for the histone acetyltransferase activities of SAGA and elongator in vivo. EMBO J. 2000;19:3060–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pokholok DK, Hannett NM, Young RA. Exchange of RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation factors during gene expression in vivo. Mol Cell. 2002;9:799–809. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert C, Kristjuhan A, Winkler GS, Svejstrup JQ. Elongator interactions with nascent mRNA revealed by RNA immunoprecipitation. Mol Cell. 2004;14:457–64. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahl PB, Chen CZ, Collins RN. Elp1p, the yeast homolog of the FD disease syndrome protein, negatively regulates exocytosis independently of transcriptional elongation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:841–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang B, Johansson MJ, Byström AS. An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the Elongator complex. RNA. 2005;11:424–36. doi: 10.1261/rna.7247705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Close P, Hawkes N, Cornez I, Creppe C, Lambert CA, Rogister B, et al. Transcription impairment and cell migration defects in elongator-depleted cells: implication for familial dysautonomia. Mol Cell. 2006;22:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardiner J, Barton D, Marc J, Overall R. Potential role of tubulin acetylation and microtubule-based protein trafficking in familial dysautonomia. Traffic. 2007;8:1145–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creppe C, Malinouskaya L, Volvert ML, Gillard M, Close P, Malaise O, et al. Elongator controls the migration and differentiation of cortical neurons through acetylation of alpha-tubulin. Cell. 2009;136:551–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada Y, Yamagata K, Hong K, Wakayama T, Zhang Y. A role for the elongator complex in zygotic paternal genome demethylation. Nature. 2010;463:554–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esberg A, Huang B, Johansson MJ, Byström AS. Elevated levels of two tRNA species bypass the requirement for elongator complex in transcription and exocytosis. Mol Cell. 2006;24:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agris PF, Vendeix FA, Graham WD. tRNA’s wobble decoding of the genome: 40 years of modification. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Björk GR. Biosynthesis and Function of Modified Nucleosides. In: RajBhandary DSaU, ed. tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Fundtion. Washington: American Society for Microbiology, 1995:165-205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki T. Biosynthesis and function of wobble modifications. In: Grosjean H, ed. Fine-tuning of RNA functions by modification and editing. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarian C, Marszalek M, Sochacka E, Malkiewicz A, Guenther R, Miskiewicz A, et al. Modified nucleoside dependent Watson-Crick and wobble codon binding by tRNALysUUU species. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13390–5. doi: 10.1021/bi001302g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vendeix FA, Murphy FV, 4th, Cantara WA, Leszczyńska G, Gustilo EM, Sproat B, et al. Human tRNA(Lys3)(UUU) is pre-structured by natural modifications for cognate and wobble codon binding through keto-enol tautomerism. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:467–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy FV, 4th, Ramakrishnan V, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys)UUU. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1186–91. doi: 10.1038/nsmb861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewez M, Bauer F, Dieu M, Raes M, Vandenhaute J, Hermand D. The conserved Wobble uridine tRNA thiolase Ctu1-Ctu2 is required to maintain genome integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5459–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709404105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leidel S, Pedrioli PG, Bucher T, Brost R, Costanzo M, Schmidt A, et al. Ubiquitin-related modifier Urm1 acts as a sulphur carrier in thiolation of eukaryotic transfer RNA. Nature. 2009;458:228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noma A, Sakaguchi Y, Suzuki T. Mechanistic characterization of the sulfur-relay system for eukaryotic 2-thiouridine biogenesis at tRNA wobble positions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1335–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang B, Lu J, Byström AS. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for formation of the wobble nucleoside 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2008;14:2183–94. doi: 10.1261/rna.1184108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glatt S, Létoquart J, Faux C, Taylor NM, Séraphin B, Müller CW. The Elongator subcomplex Elp456 is a hexameric RecA-like ATPase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:314–20. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemau de Talancé V, Bauer F, Hermand D, Vincent SP. A simple synthesis of APM ([p-(N-acrylamino)-phenyl]mercuric chloride), a useful tool for the analysis of thiolated biomolecules. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:7265–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer F, Matsuyama A, Yoshida M, Hermand D. Determining proteome-wide expression levels using reverse protein arrays in fission yeast. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1830–5. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer F, Matsuyama A, Candiracci J, Dieu M, Scheliga JS, Wolf DA, et al. Translational control of cell division by elongator. Cell Rep. 2012;1:424–33. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Fazly AM, Zhou H, Huang S, Zhang Z, Stillman B. The elongator complex interacts with PCNA and modulates transcriptional silencing and sensitivity to DNA damage agents. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, Huang B, Eliasson M, Rydén P, Byström AS. Elongator complex influences telomeric gene silencing and DNA damage response by its role in wobble uridine tRNA modification. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Tuck S, Byström AS. Defects in tRNA modification associated with neurological and developmental dysfunctions in Caenorhabditis elegans elongator mutants. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solinger JA, Paolinelli R, Klöss H, Scorza FB, Marchesi S, Sauder U, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans Elongator complex regulates neuronal alpha-tubulin acetylation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akella JS, Wloga D, Kim J, Starostina NG, Lyons-Abbott S, Morrissette NS, et al. MEC-17 is an alpha-tubulin acetyltransferase. Nature. 2010;467:218–22. doi: 10.1038/nature09324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shida T, Cueva JG, Xu Z, Goodman MB, Nachury MV. The major alpha-tubulin K40 acetyltransferase alphaTAT1 promotes rapid ciliogenesis and efficient mechanosensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013728107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cueva JG, Hsin J, Huang KC, Goodman MB. Posttranslational acetylation of α-tubulin constrains protofilament number in native microtubules. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1066–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Topalidou I, Keller C, Kalebic N, Nguyen KC, Somhegyi H, Politi KA, et al. Genetically separable functions of the MEC-17 tubulin acetyltransferase affect microtubule organization. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1057–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fersht N, Hermand D, Hayles J, Nurse P. Cdc18/CDC6 activates the Rad3-dependent checkpoint in the fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5323–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bamps S, Westerling T, Pihlak A, Tafforeau L, Vandenhaute J, Mäkelä TP, et al. Mcs2 and a novel CAK subunit Pmh1 associate with Skp1 in fission yeast. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alfa CE, Hyams JS. Microtubules in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe contain only the tyrosinated form of alpha-tubulin. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1991;18:86–93. doi: 10.1002/cm.970180203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeeberg BR, Qin H, Narasimhan S, Sunshine M, Cao H, Kane DW, et al. High-Throughput GoMiner, an ‘industrial-strength’ integrative gene ontology tool for interpretation of multiple-microarray experiments, with application to studies of Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]