Abstract

Past examinations of the impact of chronic illness on identity have focused primarily on positive adaptation, i.e., benefit finding or posttraumatic growth. Given that associations between these constructs and psychosocial wellbeing are equivocal, greater investigation is needed into interactions among perceived positive and negative identity changes pursuant to illness. A cross-sectional study was conducted between 2006 and 2007 with an ethnically diverse sample of 129 HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Participants completed a brief quantitative survey, including a new measure, the Impact on Self-Concept Scale (ISCS), as well as gay-related stigma, quality of life, and regulatory focus. Factor analysis supported the existence of two ISCS subscales: self-growth and self-loss. Both subscales demonstrated strong internal consistency and were modestly and positively correlated. Preliminary assessment of construct validity indicated distinct patterns of association, with self-loss being more strongly associated with stigma and quality of life than self-growth. In multivariate models, associations between self-loss and both quality of life and regulatory focus were moderated by self-growth. The ISCS demonstrated preliminary reliability and validity in this sample. Findings suggest that self-growth and self-loss are meaningfully distinct constructs that may interact to produce important implications for understanding the experience of chronic illness.

Keywords: HIV, Self-Concept, Posttraumatic Growth, Stigma, Quality of Life, Gay and Bisexual Men

INTRODUCTION

Research on adjustment to chronic illness indicates that many individuals report experiencing positive personal changes following diagnosis or over the course of treatment. Among the various terms that have been used for this phenomenon, posttraumatic growth describes a process through which individuals experience a positive transformation as a direct result of their struggle with adversity (1). Posttraumatic growth has been associated with better psychosocial well-being and lower affective distress across a host of chronic illnesses, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and HIV (2-8).

The underlying premise of posttraumatic growth is that the experience of adversity can alter one’s view of self and the world, generating psychological distress. However, through evaluating these experiences, a new sense of meaning and self-worth can emerge (9). Meaning making can be accompanied by periods of distress, as individuals accommodate to adverse circumstances into their understanding of themselves and the world, and set new life goals and priorities (10). Within the posttraumatic growth literature, three common categories of growth outcomes have been identified: relationship enhancement (i.e., increased valuation of friends and family, increased intimacy in personal relationships), change in life philosophy (i.e., greater appreciation of life, altered sense of priorities, enhanced spiritual beliefs), and changes in views of the self (i.e., greater sense of wisdom, strength or resiliency, recognition of new possibilities or paths for life) (11, 12). Across a range of illnesses, a large percentage of patients – anywhere from 59 to 83 percent – report growth experiences (13, 14).

Although these growth experiences have been described in positive terms, evidence regarding the association between posttraumatic growth and psychosocial wellbeing or physical health is equivocal. Some studies have demonstrated a positive association between growth and wellbeing in both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs (3, 7, 8, 13, 15, 16), while others find a positive association between growth and psychological distress (17, 18), and still others find no evidence of a significant association either cross-sectionally (2, 19, 20) or longitudinally (3, 14). In one meta-analysis that surveyed studies of multiple chronic illnesses and other stressful life events, growth was associated with more positive affect and less depression, but was unrelated to anxiety, distress, quality of life, or subjective health (21). Researchers have noted that these inconsistencies do not appear to be due to differences in measurement since each measure has resulted in both significant and non-significant findings (22).

Several theories have been put forth to explain these equivocal findings. Some evidence suggests a curvilinear relation between growth and health outcomes, such that individuals at both the high and low end of perceived growth report the best psychological health over time (23). Evidence also suggests that demographic factors, including age, gender and race/ethnicity, time since diagnosis, or symptom severity may moderate the association between posttraumatic growth and wellbeing (21, 22, 24). Additional research has suggested that posttraumatic growth is an outcome in and of itself, acting as an independent dimension of wellbeing that need not be correlated with other measures of health or distress (25). Others have suggested that posttraumatic growth may serve as a stress-buffer in the face of affective distress for individuals living with chronic illness (10, 26). Of the few studies that have examined the potential stress moderating role of growth perceptions, Siegel & Schrimshaw (22) found growth to have a moderating effect on the distress and well-being for women living with HIV/AIDS. Moreover, among the women who reported few benefits of their illness, high levels of physical symptoms were associated with greater psychological distress than among women who reported greater benefits of illness, suggesting that growth may serve as a protective psychosocial resource in the face of adversity.

Another explanation for these contradictory findings challenges the framing of growth studies in their focus almost exclusively on positive changes following adversity (24, 27). In addition to concerns about potential response bias which might blur significant associations, some researchers argue that perceived growth following trauma will have beneficial effects only on those who also acknowledge its costs (28). There is some evidence that perceived benefits associated with adversity are more strongly associated with psychosocial wellbeing and resources for those who report mixed accounts that include both positive and negative effects of a given event (27, 29).

Loss is explicitly recognized in the literature on posttraumatic growth, which acknowledges that the negative nature of the event and its sequelae are still viewed as undesirable, even if positive change has resulted from them (12). However, much of the literature assumes that growth and other benefits stem directly from losses, suggesting that loss lies on the opposite end of the growth spectrum and may be diminished to the extent that true growth is achieved. In contrast, research on the purported independence of positive and negative affective systems (30-33) suggests that perceptions of growth and loss following adversity may be orthogonal constructs, operating independently and in interaction in their influence on wellbeing. The literature on chronic illness and identity contains themes of loss, negative experiences of living with a disease, and its acceptance and denial (34, 35). Among the three domains of growth outcomes that we reviewed previously, changes in views of the self appears to be the one most amenable to simultaneous perceptions of both growth and loss (36, 37). Previous examination of self-related cognitions among individuals living with chronic illness lend credence to the distinction between positive and negative impacts of illness on identity and suggest that these factors are differentially associated with both physical and mental health outcomes (4). In a sample of HIV-positive women, Updegraff and colleagues (7) found that positive and negative changes resulting from illness were inversely correlated such that those who reported greater benefits from being HIV-positive reported fewer losses due to HIV. However, the authors found that there was less self-reported depression among those women who reported exclusively positive changes resulting from HIV when compared to those who reported only negative changes or those who reported both negative and positive changes. These reports are consistent with research that illustrates that between 59% and 83% of HIV-positive individuals report positive changes since diagnosis (6, 13), but it is also worth noting that the majority of women in this sample endorsed both positive and negative changes as a result of HIV. Similarly, posttraumatic growth has been shown to interact with negative components of illness to predict psychological wellbeing (22) and physical health indicators, such as viral load (38). Taken together, these findings suggest that growth and loss may be independent and meaningful constructs for examining adaptation processes among individuals living with HIV.

The present study describes the development and pilot testing of a new measure, called the Impact on Self Concept Scale (ISCS). Building upon previous mixed-methods approaches to examining positive and negative HIV-related identity changes (7), we sought to develop a quantitative measure that would capture both self-growth and self-loss simultaneously. The aims of the study were twofold. First, we sought to examine preliminary evidence of the scale’s structure and internal consistency based on a diverse sample of gay and bisexual men living with HIV. The ISCS was designed to include both positive and negative aspects of the impact of illness on identity. Based on previous research (7, 22), we expected that the items would emerge as distinct subscales rather than as opposite ends of a single construct and we sought to explore the extent to which these subscales might be associated with each other.

Our second aim was to examine preliminary validity by exploring the scale’s association with three other relevant measures. First, we examined perceived quality of life. The literature on posttraumatic growth consistently finds strong and positive associations between growth and perceived positive mental health outcomes, including quality of life (14, 18, 21). We hypothesized that quality of life would be positively correlated with the positive, self-growth ISCS subscale, and would be negatively correlated with negative, self-loss subscale. Second, we examined gay-related stigma. Gay-related stigma has important implications for identity for many gay and bisexual men, and has been associated with negative psychological and physical health, independent of HIV infection (39, 40). However, research on HIV-positive gay and bisexual men suggests that gay-stigma is often exacerbated among infected individuals, because of the extent to which the disease is associated with negative attitudes toward homosexuality (41, 42). As such, this measure was included as preliminary evidence of discriminant validity, to assess the extent to which the ISCS measures aspects of identity more specific to HIV infection itself. We hypothesized that the negative ISCS subscale would be modestly positively correlated with gay stigma, but that the correlation between the ISCS and quality of life would be of greater magnitude than the correlation between quality of life and gay stigma. Finally, we examined regulatory focus. Regulatory focus refers to an individual’s self-regulation strategies that are used to guide him or her in pursuit of specific goals. Promotion-focus refers to self-regulatory strategies that emphasize pursuit of gains, while prevention-focus refers to strategies that emphasize the avoidance of losses (43). As such, we hypothesized that a promotion focus would be associated with the positive ISCS subscale, and that prevention focus would be associated with the negative ISCS subscale.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

The analyses for this paper were conducted as a secondary data analysis of the Sex and Love Survey version 8.0, within which we were able to include a version of the newly developed ISCS measure for pilot testing of its psychometric properties. Participants were 129 ethnically diverse HIV-positive men surveyed at a series of gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) community events in New York City (NYC) in the fall of 2006 and the spring of 2007. Each event lasted two to three days – one of these events was a large, sex-themed event that includes booths advertising sexual websites, selling pornography and sex toys, and hosting various types of performances and the second is a large, more generally-themed LGBT event that includes booths for community-based organizations, political groups, commercial advertisements (e.g., cruises and other forms of travel), and a variety of other LGBT-oriented groups and businesses. Both events charge a small free for general admission. Participants were recruited using an adaptation of a cross-sectional, brief-intercept sampling method (44), as part of the Sex and Love Study. These methods have been utilized previously by the research team (e.g., 45, 46) as well as other researchers (e.g., 47, 48, 49), and research suggests they produce results comparable to more rigorous methods, such as time-space sampling (50).

At each community event, the research team hosted a booth and research staff approached attendees and offered them the opportunity to participate. Participants were eligible for the survey if they were male, at least 18 years of age, and reported sex with other men. Consistent with rates from previous studies (44), a high percentage of individuals approached (83%) agreed to participate. Participants completed a 10-15 minute paper and pencil survey and received a free movie pass as an incentive. To enhance confidentiality, participants were given a clipboard with the survey so that they could step away from the booth and complete it in privacy. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hunter College of the City University of New York. Of the 818 men who completed the survey, 133 men reported being HIV-positive. Of those, 4 had missing data on the Impact on Self-Concept Scale, leaving an analytic sample of 129 men.

The mean age of participants was 42.46 years (SD = 10.12, range = 18-54). A total of 47% (n = 61) of participants were White, 23% (n = 30) were Black, 25% (n = 32) were Latino, and 5% (n = 6) reported being another race/ethnicity or of multiple races. About two-thirds (68%, n = 88) had a bachelor’s degree or more education; 19% (n = 25) reported annual income less than $20,000, 46% (n = 59) reported annual income between $20,000 and $60,000, and 30% (n = 38) reported annual income over $60,000. About 41% (n = 53) reported being partnered. Almost half of participants (50%, n = 64) reported having been diagnosed with HIV more than ten years ago, 17% (n = 22) reported living with HIV for 5-9 years, 25% (n = 32) reported living with HIV for 1-4 years, and 9% (n = 11) reported having been diagnosed with HIV within the last year.

Development of the Impact on Self Concept Scale (ISCS)

Prior to pilot testing the measure in the current study, an iterative free-listing approach was used to generate scale items in consultation with researchers with expertise in the area of adaptation to chronic illness. Items were to be related to the underlying constructs by including both positive and negative dimensions of illness and identity. Initially, a total of 24 items were generated. These items were vetted by a small group of key informants, and then grouped into categories designed to be theoretically meaningful for the latent constructs of self-growth and self-loss. Following feedback on the items, they were paired down until ten items related to positive and negative aspects of impact on self-concept that each reflected a similar level of specificity in content remained (51). Participants were asked to respond to both positive (e.g. “Living with HIV has taught me that I can handle anything”) and negative (e.g., “Being HIV-positive has made me lose part of who I am”) items by indicating how often the feel similarly to each statement, using a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). The wording of all 10 items can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of a Principal-Components Factor Analysis of the 10-item Impact of HIV on Self-Concept Scale

| Item no. | Item | 2-factor solution

|

% endorsinga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 “self-loss” | Factor 2 “self-growth” | |||

| 7 | Being HIV+ limits me | 0.84 | b | 45 |

| 3 | Being HIV+ has made me lose a part of who I am | 0.83 | b | 36 |

| 9 | It’s hard to think of myself without thinking of HIV | 0.78 | b | 37 |

| 10 | HIV is too present in my life | 0.74 | b | 40 |

| 5 | I feel stigmatized by being HIV+ | 0.73 | b | 44 |

| 1 | HIV prevents me from doing things that are important to me | 0.71 | b | 31 |

| 8 | Being HIV+ affects every part of my life | 0.67 | b | 42 |

| 4 | Being HIV+ has helped me focus on the important things in life | b | 0.91 | 71 |

| 6 | Being HIV+ has taught me that I can handle anything | b | 0.84 | 65 |

| 2 | Living with HIV has helped me to grow as a person | b | 0.81 | 65 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.22 | 2.12 | ||

| % of variance | 42.20 | 21.15 | ||

| Range | 1 – 6 | 1 – 6 | ||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.88 | 0.82 | ||

Note.

Indicates the percentage of people who responded 4 (often), 5 (most of the time), or 6 (always).

Blank cells indicate factor loadings less than the absolute value of .20. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling = .82

Measures

For these analyses we chose several psychosocial variables that we felt were relevant from those measures that were also included within this brief survey. We acknowledge from the outset that there are other constructs that would be even more relevant for establishing the validity of this scale, including HIV stigma and mental health variables such as depression or anxiety. However, we believe the following variables provide preliminary evidence of this scale’s utility given the limited nature of the brief survey and we describe our rationale for the inclusion of each along with its description.

Quality of life

Participants completed the Linear Analogue Scale Assessment of Quality of Life (LASA-QL), which is a linear analogue scale in which participants are asked to rate their overall quality of life by marking an “X” along a line which is anchored by “as good as it could possibly be” and “as bad as it could possibly be” (52). The LASA-QL has been found to have good reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, and acceptability to patients (53), including HIV-positive persons (54). The LASA-QL yields a continuous quality of life score from 0 to 10 based on the number of centimeters from the left-hand anchor, with higher scores indicating more positive quality of life ratings.

A total of 53 participants accidentally skipped the single-item QOL scale. Unfortunately, the VAS-style line for this scale was located on the bottom right-hand corner of the self-report survey page, and several participants reported confusing this line with other dividing lines throughout the survey, inadvertently skipping the question. Participants with missing data on the QOL scale did not differ from those with complete data by age, education, income, relationship status, or years since HIV diagnosis. Individuals with missing data were more likely to report a White racial background compared to those with complete data. Participants who skipped the QOL item were not significantly different from those who completed it in terms of their self-growth scores. However, those who skipped the item had higher self-loss scores (M = 3.26, SD = 1.34) than those who answered it (M = 2.68, SD = 1.18), p =.01. Because mean-centering is intended to improve interpretability of the model, the self-growth and self-loss scores were re-centered for the analysis involving QOL such that they were centered on the mean for only those who provided data for the QOL variable.

Gay-related stigma

Participants completed the 10-item Personalized Gay-Related Stigma Subscale (39) to examine stigma and other social consequences gay and bisexual men have faced as a result of their sexual orientation. The scale contains items such as “I regret having told some people I’m gay/bi” and “I have lost friends by telling them I’m gay/bi” that are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Reliability in this sample was excellent (α = .91).

Regulatory focus

Participants completed the Prevention/Promotion Scale (55), adapted to exclude two items relevant only to college students (i.e., those that ask specifically about “academic ambitions” and “academic failure”). The scale consists of two 8-item subscales rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (very true). The prevention focus subscale measures the extent to which people are motivated by the avoidance of negative outcomes in life, with items such as “I often think about the person I am afraid I might become in the future” and “I am more oriented towards preventing losses than I am towards achieving gains.” The promotion focus subscale has items that measure the extent to which people are motivated by the pursuit of desirable outcomes, such as “I often think about the person I would ideally like to be in the future” and “In general, I am focused on achieving positive outcomes in my life.” Reliability scores in this sample were consistent with those found in past research (promotion α = .83, prevention α = .71).

Analytic Plan

Principal components factor analysis (conducted in SPSS version 17.0) was used to examine the underlying factor structure of the ten items measuring the impact of HIV on self-concept. Because two distinct factors emerged that corresponded to hypothesized self-concept components, we conducted both orthogonal (Equamax) and oblique (Promax) rotations to examine whether the assumption of uncorrelated subscales was met or if an oblique rotation was necessary. Subscale scores were then created by averaging participants’ scores on the relevant items corresponding to the two factors identified.

Pearson’s correlations and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests were used to examine demographic differences in sub-scale scores. Bivariate correlations were then conducted to examine associations among subscale scores and the measures of quality of life, stigma, and regulatory focus. As discussed in more detail within the results section, these two subscales were weakly and positively associated with each other. Given the unexpected positive association between the two subscales and the stress-buffering associations found in prior research, we hypothesized that the two subscales might interact with each other in a meaningful way and tested this within the multivariable models. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which the two subscales and their interaction were associated with these measures. In these analyses, both subscales were mean centered and entered in the first step (56) and their interaction was entered on the second step. Significant interactions were interpreted by plotting the predicted means for each variable at ± 1 standard deviation to form the high (+1 SD) and low (-1 SD) groups.

Missing Data

One participant skipped the gay-related stigma scale on his survey, and is excluded only in analyses where gay-related stigma is a variable of interest. Within our description of the quality of life measure above we describe the issue of missing data further for that specific instrument.

RESULTS

Factor Structure and Reliability of the Impact on Self-Concept Scale

Descriptive statistics and factor loadings for each of the ten ISCS items are presented in Table 1, including eigenvalues, percentage of variance accounted for by each factor, item factor loadings for the two-factor solution with Promax rotation, and the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α) for each factor. The PCA revealed two distinct subscales, and as such we conducted a second analysis that included rotation for an enhanced factor solution. Both orthogonal (Equamax) and oblique (Promax) rotations were used (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling = .82). The two distinct factors corresponded with the conceptually based components of growth and loss. Because the two factors had a statistically significant correlation with each other, results of the oblique rotation are reported. Both factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0, and were the only plausible factors based on Cattel’s scree test. Seven items loaded onto the first factor, termed “self-loss,” which accounted for 42% of the total variance. Three items loaded onto the second factor, termed “self-growth,” which accounted for an additional 21% of the total variance.

Both factors demonstrated strong internal consistency and accounted for much of the variance in the item responses. Both scales were fairly normally distributed (skewness/SE skewness < 3 for both variables) and both scales ranged from 1 to 6. In general, growth items were more strongly endorsed than loss items, with a mean of 4.08 (SD = 1.44) compared to a mean of 2.92 (SD = 1.28), respectively. The results of the exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation suggested that the two subscales were weakly and positively associated with each other, which was contrary to what might be hypothesized intuitively but was consistent with some existing literature regarding their co-occurrence. Given the exploratory focus of these analyses, we hypothesized the possibility of a statistical interaction between the two in their effect on the psychosocial variables of interest and test for this in later analyses.

Demographic Differences Among Self-Loss and Self-Growth Scores

In order to examine demographic differences in self-loss and self-growth subscale scores, one-way ANOVAs were performed on ethnicity (White, Black, Latino, Other), age (18-29 years, 30-44 years, 45+ years), education (less than a bachelor’s degree, bachelor’s degree or more), income (less than $20k per year, $20k to $60k per year, more than $60k per year), relationship status (single, partnered), and time since HIV diagnosis (within the past year, 2-4 years ago, 5-9 years ago, more than 10 years ago). There were no statistically significant differences in self-loss or self-growth scales by any demographic variable using the standard p-value of .05 (data not shown).

Examination of the Association between ISCS Subscales and other Variables

Table 2 summarizes the correlations between the ISCS subscales and other variables of interest. Self-loss and self-growth were slightly positively correlated, r(127) = .18, p < .05, but the magnitude and sign of this correlation support their designation as discrete and co-occurring constructs rather than opposite ends of a single construct. At the bivariate level, the self-growth subscale was not significantly correlated with any of the four psychosocial indicators. The self-loss subscale was significantly positively correlated with gay-related stigma, r(126) = .50, p < .001, and prevention focus, r(127) = .34, p < .001, and was negatively correlated with quality of life, r(74) = -.23, p = .05.

Table 2.

Sample Means, SDs, and Pearson Correlation Coefficients Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Growth scale | -- | |||||

| 2. Loss scale | 0.18* | -- | ||||

| 3. Stigma | -0.06 | 0.50*** | -- | |||

| 4. Promotion | 0.17 | -0.11 | -0.15 | -- | ||

| 5. Prevention | 0.00 | 0.34*** | 0.27** | 0.28*** | -- | |

| 6. Quality of Life | 0.11 | -0.23* | 0.00 | 0.09 | -0.29** | -- |

|

| ||||||

| M | 4.06 | 2.92 | 18.50 | 31.74 | 24.92 | 7.57 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.28 | 7.42 | 5.86 | 5.74 | 1.98 |

Note.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the main and two-way interaction effects of self-loss and self-growth on the four psychosocial indicators of interest – gay-related stigma, overall quality of life, promotion focus, and prevention focus. The results of these regression models are shown in Table 3. In the model predicting gay-related stigma, the two ISCS subscales accounted for 28% of the variance. Self-growth was significantly negatively associated with gay-related stigma and self-loss was significantly positively associated with gay-related stigma. It is important to note that there was no association between self-growth and gay-related stigma at the bivariate level, but that this association emerged when self-loss was considered simultaneously. There was no evidence of an interaction effect.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses of the Association between Self-Growth, Self-Loss, and Psychosocial Indicators

| Predictors | Stigma | Quality of Life | Promotion | Prevention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | |

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | 0.28*** | 0.07 | 0.05* | 0.12*** | ||||

| Self-Growth | -0.16* | 0.12 | 0.19* | -0.06 | ||||

| Self-Loss | 0.53*** | -0.23** | -0.14 | 0.35*** | ||||

| Step 2 | 0.00 | 0.05* | 0.01 | 0.03* | ||||

| Growth × Loss | -0.02 | 0.24* | 0.11 | 0.19* | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total R2 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.15 | ||||

| Total F | 15.83*** | 3.07* | 2.52 | 7.19*** | ||||

| df | 1, 124 | 1, 72 | 1, 125 | 1, 125 | ||||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Note: See methods section for a description of missing data.

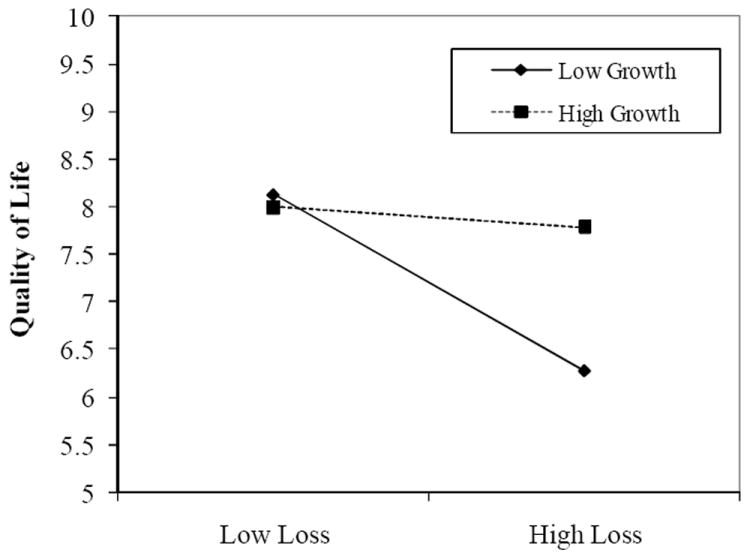

In the model predicting quality of life, the subscales accounted for 7% of the variance in the first step and their interaction term accounted for an additional 4% of variance in the second step. Self-loss was significantly and negatively associated with quality of life as a main effect, but the coefficient for self-growth main effect was not significant. The interaction term is depicted in Figure 1. Individuals who reported low levels of self-loss reported relatively high quality of life, regardless of their self-growth scores. However, for individuals who reported high levels of self-loss, those who reported low levels of self-growth reported significantly lower quality of life scores compared to those who reported high levels of self-growth.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Self-Loss and Self-Growth in Predicting Quality of Life Ratings (n = 76).

In the model predicting promotion focus, the two subscales accounted for 6% of the variance, and their interaction was not significant. Only the coefficient for self-growth was significantly positively associated with promotion focus. Again, it is important to note that there was no association between self-growth and promotion focus at the bivariate level, but that this association emerged when self-loss was entered simultaneously into the model.

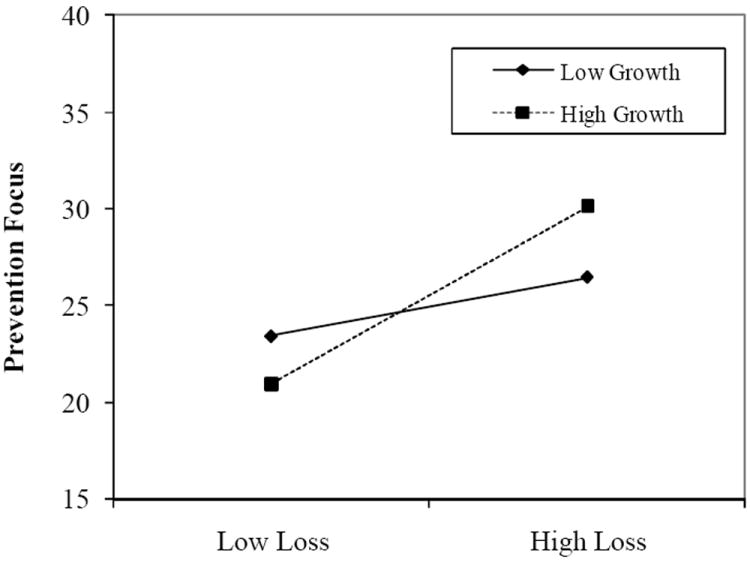

In the model predicting prevention focus, the subscales accounted for 12% of the variance, and their interaction term accounted for an additional 3% of the variance in the second step. Self-loss was significantly and positively associated with prevention focus as a main effect, but the coefficient for self-growth was not significant on its own. The interaction is depicted in Figure 2. In this analysis, individuals with low self-growth scores reported similar levels of prevention focus, regardless of their self-loss scores. However, for individuals with high self-growth scores, those who reported high self-loss were more prevention focused than those who reported low self-loss.

Figure 2.

Interaction between Self-Loss and Self-Growth in Predicting scores on Prevention Focus (n = 129)

DISCUSSION

The Impact on Self-Concept Scale (ISCS), designed for this study to be a measure of an individual’s perception of HIV to their sense of self, demonstrated good psychometric properties in this sample of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Factor analysis supported the existence of two meaningfully distinct subscales that we termed self-growth and self-loss. At the level of face validity, the self-growth factor appears similar to past research on benefit finding or posttraumatic growth, and we confirmed the presence of a second factor that specifically assessed feelings of self-loss. We found that participants endorsed experiences of self-growth more strongly than those of self-loss and found evidence for a relatively small yet positive association between the two constructs, suggesting the two co-occur within individuals. In light of these findings and given previous research on the stress-buffering effects of posttraumatic growth, we tested an interaction between the two subscales and found preliminary evidence that self-loss appears to interact with self-growth to influence psychosocial wellbeing in this sample. The distinctiveness of these two identity-related processes may have important implications for understanding the experience of chronic illness.

There were no demographic differences in self-growth or self-loss scores, but each subscale was associated with different psychosocial indicators, providing preliminary evidence of discriminant validity. In addition, the associations between each subscale and psychosocial variables of interest became particularly relevant in the context of the other, and there was evidence that self-growth moderated the effect of self-loss on certain indicators.

Gay-related stigma was only associated with self-loss at the bivariate level, but was positively associated with loss and negatively associated with self-growth in the multivariable model. These findings may make intuitive sense, but it is important to note that the stigma assessed in this study was gay-related stigma, not HIV-related stigma. There has been considerable research conducted on the impact of HIV-stigma on the lives of HIV-positive individuals (57, 58), but less research exists on the impact of gay-related stigma on the ways in which HIV-positive gay and bisexual men experience their illness and its impact on their identity (59). Similarly, there has been scant research on the association between HIV stigma and benefit finding or post-traumatic growth. In one study, stigma and growth were conceptualized as two opposite ends of a spectrum of disclosure experiences for HIV-positive women; while some women experienced some rejection, stigma and isolation, others reported that their relationships with other became closer as a result of HIV/AIDS (6). Findings from the present study suggest the importance of exploring not only HIV-stigma, but also the role of gay stigma in adjustment to chronic illness for HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Given the historical conflation of gay and HIV stigma (60), these findings may also illustrate how experiences of stigma may be associated with identity-related constructs such as self-loss even when the domain of the stigma is not specific to the identity of interest. Alternatively, given the potential co-occurrence of gay and HIV-related stigmas, it is possible that gay stigma may serve as a proxy for HIV-related stigma in some cases.

Quality of life was significantly negatively associated with self-loss, but this association was moderated by perceptions of self-growth. These findings may partially explain some of the equivocal findings in the literature on benefit-finding or post-traumatic growth (24), suggesting that posttraumatic growth may serve as a stress-buffer in the face of affective distress for individuals living with chronic illness (10, 26). In contrast with previous studies (22), we found that self-growth in our sample was a relevant buffer only for individuals who also reported high levels of self-loss. Thus, it is possible that studies examining posttraumatic growth or benefit finding without exploring constructs associated with self-loss may be obscuring significant associations that occur for some but not all individuals. In their description of the concept of posttraumatic growth, Tedeschi and Calhoun (12) argue that an event must be significant enough to cause disruption in core beliefs or assumptions about the self to initiate the cognitive processing necessary for growth. Although our data suggest that individuals may report self-growth even in the absence of perceived self-loss, these findings are consistent with the assertion that self-growth impacts quality of life only for those individuals who are experiencing self-loss. These data suggest the importance of adding measures of self-loss to future investigations of the impact of posttraumatic growth on quality of life for individuals living with chronic illness. The presence of an interaction between growth and loss on quality of life also provides unexpected yet meaningful evidence of construct validity and the importance of examining the two constructs together.

The associations between growth and loss subscales and regulatory focus may provide some insight into the psychological antecedents or consequences of these processes. It was expected that self-growth would be positively associated with promotion focus (i.e., motivation to attain desirable outcomes) and self-loss would be positively associated with a prevention focus (i.e., motivation to avoid undesirable outcomes) as evidence of construct validity. Interestingly, the association between self-growth and promotion focus became significant only when adjusting for self-loss, and the association between self-loss and prevention focus was moderated by self-growth. Because these are correlational data, it is impossible to determine whether pre-existing regulatory focus shapes the experience of the impact of illness on identity, or whether this experience influences regulatory focus. It is important to note, however, that the regulatory focus measure is general, and does not ask specifically about illness-related motivation, suggesting that it is examining a personality trait rather than an idiosyncratic response to a particular stressor. Recent explorations of adaptation to negative life events have called for increased integration of literature on coping and self-regulation (61). Further research is needed into the association between identity processes and regulatory focus, and into their implications for behavioral and mental health outcomes.

There are several limitations of the present study that should be considered in future research. First, we included this scale within a survey for which the primary focus was neither on the development of this new measure nor on HIV-positive issues in general. As such, this secondary data analysis was limited in the number and type of psychosocial measures that we were able to utilize for establishing its validity. Nonetheless, we believe that the available scales were relevant to the newly developed scale and provided preliminary evidence of its utility even though they may not have been as applicable as other measures. A more comprehensive psychometric assessment of the ISCS must include its association with established measures of benefit-finding or posttraumatic growth, measures that are more relevant to the study of adjustment to HIV (e.g., HIV-related stigma and mental health), and its association with HIV infection itself (e.g., years living with HIV, CD4 count, viral load). Future research is needed to identify the extent to which this new measure is related to and distinct from these other relevant constructs. Second, the sample was restricted to gay and bisexual men with HIV infection living in New York City. These data do not allow for the assessment of gender or sexual orientation differences in subscale scores, and they are specific to a particular chronic illness. Further research is needed into whether the constructs of self-growth and self-loss are applicable across populations and across illnesses. At the same time, it is important to note that the sample was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, age, income, education, and relationship status, indicating some degree of generalizability of the findings. Third, because of the placement of the VAS-style QOL scale on the paper survey, there was a large amount of missing data on that item. Future studies should more fully examine the impact of self-growth and self-loss on quality of life; however, the significant study results even with the reduced power inherent in this smaller sample lends credence to these pilot findings.

As with all cross-sectional, self-report surveys, the data prevent us from being able to establish any temporal or causal interpretations of the findings. A recent meta-analysis of research on posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals living with HIV and cancer found that time since diagnosis significantly moderated the association between posttraumatic growth and both positive and negative mental health (24). Although number of years living with HIV was not associated with measures of self-loss or self-growth in this sample, longitudinal research is needed to explore these associations over time.

Despite these limitations, this pilot study provides evidence of preliminary reliability and validity for a new measure of the impact of HIV on identity, which includes assessment of both self-growth and self-loss. The stress-buffering role of posttraumatic growth has been theorized in several studies (10, 22) and we found support for such a hypothesis with this new scale. In contrast to past research which has focused primarily on self-growth or other positive identity changes, these data suggest that self-loss is a powerful and distinct construct in adaptation to chronic illness. For many patients, perceptions of self-growth and self-loss appear to be orthogonal, and understanding both processes – and their mutually influential coexistence – may prove an important component of a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of illness or other major life events on self-concept.

The results of this study may also be of clinical importance for interventions that seek to promote adjustment among HIV-positive individuals. A number of clinical interventions promoting growth have proven effective (62, 63). However, these findings provide insight into some of the inconsistencies in the posttraumatic growth literature by elucidating the unique and meaningful experience of self-loss for HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. These findings provide preliminary support for the notion that improving perceptions of self-growth may not necessarily ameliorate perceptions of self-loss, but that a focus on growth may nonetheless buffer against the perceptions of self-loss. Expressive writing interventions promote attentional focus on aspects of a traumatic situation through cognitive restructuring to enhance understanding, meaning and proactive coping (63, 64). However, responses to interventions have been mixed, with some individuals showing improvement and others showing no change or worsened states (65). Thus, counselors utilizing disclosure techniques should be attuned to both self-growth and self-loss experiences, not only to promote self-growth, but also to acknowledge and seek to reduce experiences of loss. Future research is needed to identify the potential benefits of simultaneously focusing on feelings of self-loss and how reductions in such perceptions may also protect against the adverse psychosocial consequences of living with HIV.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Hunter College Center for HIV Educational Studies & Training (CHEST). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirchstein Individual Predoctoral Fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31-MH095622). The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeffrey Parsons, Dr. David Greenberg, the Sex and Love v. 8.0 study team, our interns and recruitment team, the Drag Initiative to Vanquish AIDS (DIVAs), and the research participants who gave their time and energy to the project.

References

- 1.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Future directions. In: Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG, editors. Posttraumatic growth: Positive Change in the Aftermath of Crisis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1998. pp. 215–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychology. 2001;20(3):176–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danoff-Burg S, Revenson TA. Benefit-finding among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: positive effects on interpersonal relationships. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28(1):91–103. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-2720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, Jongen PJ, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1026–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrie KJ, Buick DL, Weinman J, Booth RJ. Positive effects of illness reported by myocardial infarction and breast cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;47(6):537–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. Perceiving benefits in adversity: stress-related growth in women living with HIV/AIDS. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(10):1543–54. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Updegraff J, Taylor S, Kemeny M, Wyatt G. Positive and negative effects of HIV-infection in women with low socioeconomic resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(3):382–94. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urcuyo K, Boyers A, Carver C, Antoni M. Finding benefit in breast cancer: Relations with personality, coping, and concurrent wellbeing. Psychology & Health. 2005;20:175–92. doi: 10.1080/08870440512331317634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor SE. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist. 1983;38:1161–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran V, Wiebe DJ, Fortenberry KT, Butler CA, Berg CA. Benefit finding, affective reactions to diabetes stress, and diabetes management among early adolescents. Health Psychology. 2011;30(2):212–19. doi: 10.1037/a0022378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph S, Linley PA. Growth following adversity: theoretical perspectives and implications for clinical practice. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(8):1041–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milam J. Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34:2353–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01981.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):487–97. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carver SC, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):595–98. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(1):11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkat LP, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(4):413–19. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23(1):16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz U, Mohamed N. Turning the tide: Benefit finding after cancer surgery. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(3):653–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumalla OB. Post-traumatic growth in cancer: Reality or illusion? Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. The stress moderating role of benefit finding on psychological distress and well-being among women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(3):421–33. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lechner SC, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Phillips KM. Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):828–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Field AP. Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):436–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CL, Helgeson VS. Introduction to the special section: growth following highly stressful life events--current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):791–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMillen JC, Smith EM, Fisher RH. Perceived benefits and mental health after three types of disaster. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(5):733–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C, Wong WM, Tsang KW. Perception of benefits and costs during SARS outbreak: An 18-month prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):870–79. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Aspinwall LG. Assault on the self: Positive illusions and adjustment to threatening events. In: Strauss J, Goethals GR, editors. The Self: Interdisciplinary Approaches. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 239–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehman DR, Davis CG, Delongis A, Wortman CB, Bluck S, Mandel DR. Positive and negative life changes following bereavement and their relations to adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1993;12(1):90–112. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1993.12.1.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson D, Tellegen A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):219–35. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keyes C, Shmotkin D, Ryff C. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(6):1007–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson R, Moneta G, Richards M, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1151–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell JA, Carroll JM. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(3-30) doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charmaz K. Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1983;5(2):168–95. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charmaz K. The body, identity, and self: Adapting to impairment. Sociological Quarterly. 1994;36(657-680) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgartner LM. The incorporation of the HIV/AIDS identity into the self over time. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(7):919–31. doi: 10.1177/1049732307305881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandstrom KL. Confronting deadly disease: The drama of identity construction among gay men with AIDS. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1992;19:271–94. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milam J. Posttraumatic growth and HIV disease progression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):817–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanín JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations for sexually transmitted infections among gay men. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(4):636. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Golub SA, Walker JJ, Bamonte AJ, Parsons JT. Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety, and identification with the gay community on sexual risk and substance use. AIDS and Behavior. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0070-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner G, Brondolo E, Rabkin J. Internalized homophobia in a sample of HIV+ gay men, and its relationship to psychological distress, coping, and illness progression. Journal of Homosexuality. 1997;32(2):91–106. doi: 10.1300/J082v32n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huebner DM, Davis MC, Nemeroff CJ, Aiken LS. The impact of internalized homophobia on HIV prevention interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(3):327–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1015325303002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee AY, Gardner WL, Aaker JL. The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: The role of interdependence in regulatory focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78(6):1122–34. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller KW, Wilder LB, Stillman FA, Becker DM. The feasibility of a street-intercept survey method in an African-American community. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(4):655. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanin JE, Parsons JT. Exploring racial and ethnic differences in drug use among urban gay and bisexual men in New York City and Los Angeles. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36(2):105–23. doi: 10.2190/1G84-ENA1-UAD5-U8VJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koken JA, Parsons JT, Severino J, Bimbi DS. Exploring commercial sex encounters in an urban community sample of gay and bisexual men: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2005;17(1/2):197–213. doi: 10.1300/J056v17n01_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen JL, Kodagoda D, Lawrence AM, Kerndt PR. Rapid public health interventions in response to an outbreak of syphilis in Los Angeles. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:285–87. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gore-Felton C, Kalichman SC, Brondino MJ, Benotsch EG, Cage M, DiFonzo K. Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk among men who have sex with men: Initial test of a conceptual model. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21(4):263–70. doi: 10.1007/s10896-006-9022-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalichman SC, Simbaya L. Traditional beliefs about the cause of AIDS and AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2004;16:572–80. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halkitis P, Parsons J. Recreational drug use and HIV-risk sexual behavior among men frequenting gay social venues. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2003;14(4):19–38. doi: 10.1300/J041v14n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gough IR, Furnival CM, Schilder L, Grove W. Assessment of the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology. 1983;19(8):1161–65. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Velikova G, Stark D, Selby P. Quality of life instruments in oncology. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(11):1571–80. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ganz PA, Coscarelli Schag CA, Kahn B, Petersen L. Assessing the quality of life of HIV infected persons: Clinical and descriptive information from studies with the HOPES. Psychology & Health. 1994;9(1-2):93–110. doi: 10.1080/08870449408407462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lockwood P, Jordan CH, Kunda Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(4):854–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(6):1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chenard C. The impact of stigma on the self-care behaviors of HIV-positive gay men striving for normalcy. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2007;18(3):23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Stigma, social risk and health policy: Public attitudes towards HIV surveillance policies and the social construction of illness. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):533–40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aspinwall LG. Dealing with adversity: Self-regulation, coping, adaptation, and health. In: Schwartz ATN, editor. Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intraindividual Processes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress-management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, Collins CA, Branstetter AD. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4160–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lepore SJ, Greenberg MA, Bruno M, Smyth JM. Expressive writing and health: Self-regulation of emotion-related experience, physiology, and behaviour. In: Lepore SL, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure: How expressive writing promotes health and emotional wellbeing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:539–48. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]