Abstract

Objectives

Both peer and parental influences have been associated with the use of addictive substances in adolescence. We evaluated the relationship between the parenting style of an adolescent’s peers’ parents and an adolescent’s substance use.

Design

Longitudinal survey

Setting

Adolescents across the United States were interviewed at school and at home

Participants

Nationally representative sample of adolescents in the United States

Main Exposure

Authoritative versus neglectful parenting style of adolescent’s parents and adolescent’s friends parents; adolescent substance use

Main Outcome Measures

Adolescent alcohol abuse, smoking, marijuana use, and binge drinking

Results

If an adolescent has a friend whose mother is authoritative, that adolescent is 40% (95% CI 12%–58%) less likely to drink to the point of drunkenness, 38% (95% CI 5%–59%) less likely to binge drink, 39% (95% CI 12%–58%) less likely to smoke cigarettes, and 43% (95% CI 1%–67%) less likely to use marijuana than an adolescent whose friend’s mother is neglectful, controlling for the parenting style of the adolescent’s own mother, school level fixed effects, and demographics. These results are only partially mediated by peer substance use.

Conclusion

Social network influences may extend beyond the homogeneous dimensions of own-peer or own-parent to include extra-dyadic influences of the wider network. The value of parenting interventions should be re-assessed to take into account these spillover effects in the greater network.

Keywords: alcohol, smoking, marijuana, peer, social networks, parenting

Background and significance

Research on adolescent and adult social networks has focused on the impact of peers on risk behaviors involving drugs, tobacco, and alcohol use1–8. Networks may influence individual substance use behavior via the prevalence of substance use within the network as well as the interpersonal dynamics among network members9,10. These effects may have serious consequences; for example, the probability of a future overdose is related to both the number of members of an individual’s social network using drugs and the degree of conflict within that network11.

At the same time, there is evidence that parents may influence adolescents via their style of parenting12–14. The parenting styles framework encompasses four distinct parenting categories that are derived from two dimensions of interaction: (1) parental control (how much a parent intervenes in their adolescent child’s life) and (2) parental warmth (how much positive affect a parent shows for their adolescent). Authoritative parents are warm and communicative, but they also exert appropriate control. Neglectful parents exhibit neither warmth nor control. Authoritarian parents exert control while lacking warmth, while permissive parents show warmth but do not exert control. Studies of these four parenting styles suggest that the authoritative parenting style is optimal, with long-term benefits including academic success, positive peer relationships, minimal delinquent behavior, risk avoidance, and positive psycho-social adjustment, including higher levels of psychological well-being14–20. Adolescents with authoritative parents are also less likely to have delinquent peer networks21.

Here, we explore the possibility that parenting matters not only because of the direct and proximal effect of parent on child, but also because of the indirect and more distal relationship between a parent and their adolescent child’s friends. In other words, do the benefits of good parenting spill over, spreading from person to person and affecting multiple adolescents in a network? This question has implications both for how parents supervise the social networks of their adolescent children, as well as for how policy makers view the potential benefits of parenting education and interventions. In a previous cross-sectional study by Fletcher and colleagues, network authoritativeness (an average of the degree to which the parents of an adolescents’ peers used authoritative parenting) was correlated with a decreased propensity towards delinquency, lower levels of substance abuse, and greater psychosocial competence22. To investigate this question more thoroughly using longitudinal analyses and complete network data, we use the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health ), a source of data that contains information about adolescent social networks, their parents’ styles of parenting, and self-reported measures of substance abuse. Using longitudinal dyadic network regression models, we measure the association between an adolescent’s behavior and their friend’s behavior, their mother’s parenting style, and their friend’s mother’s parenting style.

Data

Add Health is a nationally representative study that explores multiple facets of adolescent well-being. Four waves of the Add Health study have been completed: Wave I was conducted in 1994–1995 and included adolescents who were then in grades 7th through 12th grade, Wave II in 1996, Wave III in 2001–2002, and Wave IV in 2007–2008. In Wave I of the Add Health study, researchers collected an “in-school” sample of 90,118 adolescents chosen from a nationally-representative sample of 142 schools.

As part of the survey, these students named up to 5 male and 5 female friends who were later identified from school-wide rosters to generate information about each school’s complete social network. A subset of this group was then chosen for in-depth follow-up in subsequent waves. This “in-home” sample was administered longer questionnaires about their social networks, health behaviors, family dynamics, and emotional/developmental outcomes. We drew our information about parenting and adolescent substance abuse from the Wave I and II in-home datasets.

Adolescent-friend dyads were included in each analysis only if the observations for both individuals included data on all measures of interest, and if the pair indicated that they were friends for both Wave I and Wave II. Furthermore, adolescents who indicated that they were siblings, either full or half were removed from the sample. Questions on maternal warmth were not asked of individuals for whom no one was acting in the role of mother (which could include non-biological mothers such as aunts or grandmothers). Table 1 provides summary statistics for the sample populations. Adolescents in our sample, compared to those in the complete AddHealth Wave II sample, were less likely to be black (13% vs. 23%), slightly less like to be Hispanic (13% vs. 17%), similar in likelihood to be Asian (8% vs. 7.4%), came from marginally less wealthy households (mean income 46,000 vs. 48.670) but had similar levels of parental education (mean value 5.62 vs. 5.45).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics

| N (Respondent)=1386 N (Friend)=1404 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Wave I Value | Wave II value | |

| Drunk in last year, Respondent % | 26 | 29 |

| Drunk in last year, Friend % | 29 | 31 |

| Cigarette in last month, Respondent % | 24 | 32 |

| Cigarette in last month, Friend % | 37 | 35 |

| Marijuana use in last month, Respondent % | 11 | 13 |

| Marijuana use in last month, Friend% | 14 | 16 |

| Binge drinking in last year, Respondent% | 26 | 30 |

| Binge drinking in last year, Friend% | 28 | 31 |

| Neglectful parenting, Respondent% | 24 | 28 |

| Neglectful parenting, Friend% | 25 | 33 |

| Permissive parenting, Respondent% | 22 | 30 |

| Permissive parenting, Friend% | 24 | 30 |

| Authoritarian parenting, Respondent% | 24 | 22 |

| Authoritarian parenting, Friend% | 23 | 18 |

| Age (Respondent), mean (SD) | 16.68 (1.48) | |

| Female% | 51 | |

| Household Income (1000s of Dollars), mean (SD) | 48.67 (40.48) | |

| Parent’s Education, mean (SD) | 5.62 (2.31) | |

| Hispanic % | 13 | |

| Black % | 13 | |

| Asian % | 8 | |

Note: Parent’s education is a 10 item scale (0 = never went to school; 1 = 8th grade or less; 2 = more than 8th grade, but did not graduate from high school; 3 = went to a business, trade, or vocational school instead of high school; 4 = high school graduate; 5 = completed a GED; 6 = went to a business, trade or vocational school after high school; 7 = went to college, but did not graduate; 8 = graduated from a college or university; 9 = professional training beyond a 4-year college or university)

Measures

Adolescents in the Add Health dataset responded to a battery of questions regarding their parent’s parenting behavior. Parental control was assessed using yes-no responses to seven questions from which we created a composite measure20, based on the average responses to all 7 questions (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.63).20 Adolescents whose parents were reported to exert below the median level of control are categorized as low control. Those above or equal to the median are categorized as high control. Maternal warmth was assessed using responses to five questions used in prior research20. Cronbach’s alpha on the five questions was 0.85. Warmth, like control, was categorized by placing those at the median level of warmth and above in the high-warmth parenting category, and those below the median in the low-warmth parenting category. The combination of the control and warmth categories allows us to define four different parenting types20 coded as follows: Authoritative: high warmth, high control; Authoritarian: low warmth, high control; Permissive: high warmth, low control; Neglectful: low warmth, low control. While adolescent responses regarding their parents could be biased due to respondent error, Steinberg found that adolescent report was less biased than parent self-report as parents tend to err towards depicting their own behavior in the most positive light23.

In a comprehensive section on substance use, adolescents were asked a variety of detailed questions about prior and current substance use, related to alcohol use, cigarette smoking, marijuana use, and binge drinking. We coded four separate dichotomous substance abuse outcomes from questions asked in Waves I and II to represent either having engaged in the behavior or not. For more details on variable coding please see the online supplementary appendix (OSA).

To identify the networks, we treated each friendship nomination as a “directed tie” from the namer to the named friend. We called interviewed individuals “adolescents” and the people that they named “friends”. Dyadic observations were created so that each observation included data from both an adolescent and a friend at Waves I and II for adolescent-friend pairs observed in the data. Dyads in which the adolescent and their friend were not friends in both Waves I and II were removed from the dataset. Likewise, we removed all adolescent-friend pairs for which data was missing for either the adolescent, the peer, or the peer’s parent.

Controls variables included adolescent age, race (white, Hispanic, black, or Asian), and sex. We measured socioeconomic status with two separate variables: mother’s self-reported education level, and mother’s self reported household income. Because associations between peer’s behaviors could be the result of neighborhood or other contextual factors relating to geographic proximity, we included school fixed effects in all models. This effectively eliminates any spurious correlations that may arise due to between-school variation in the incidence of the dependent variables.

While the total population for the AddHealth dataset was 20,746 for Wave I and 14,738 for Wave II, our final sample was much smaller due to our strict inclusion criteria and due to missing data on some measures. Also, our measure for SES included mother’s education, a variable that was only available among a subset of observations for whom a parent survey was conducted, which served to significantly lower the total sample size. The total number of egos was 1386 while the number of dyads used in the analyses ranged from 2003 to 2066.

Human Subjects

The research was approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, San Diego.

Analyses

We conducted separate regression analyses for each substance abuse outcome. A logit form of a general estimating equation was used to analyze each model testing the behavioral outcome of the adolescent at wave 2 as a function of friend’s mother’s parenting at wave 2, controlling for friend’s mother’s parenting at wave 1, adolescent’s and friend’s behavior at wave 1, adolescent’s mother’s parenting at both waves, gender, age, SES, and school level fixed effects (see OSA). Both adolescent and friend parenting were coded as four-category variables, with neglectful parenting used as the reference category against which the other three categories are compared (for detailed methods please see OSA).

We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) procedures to account for multiple observations of the same adolescent across ego-friend pairings and we assumed an independent working correlation structure for the clusters (See Etable 5 OSA for results of alternate analysis clustering on alters). To explore possible causal pathways by which influence may occur, we also present the results of a mediation analysis in which we tested the hypothesis that friend’s mother’s parenting influences friend’s behavior, which in turn has an effect on the adolescent’s behavior. To do so, we followed the steps of testing for mediation laid out by Baron and Kenny24, using the results of a Sobel test (for details please refer to OSA) to determine significance. For significant mediators we calculate the proportion of the main effect that is mediated by dividing the indirect effect by the main effect.

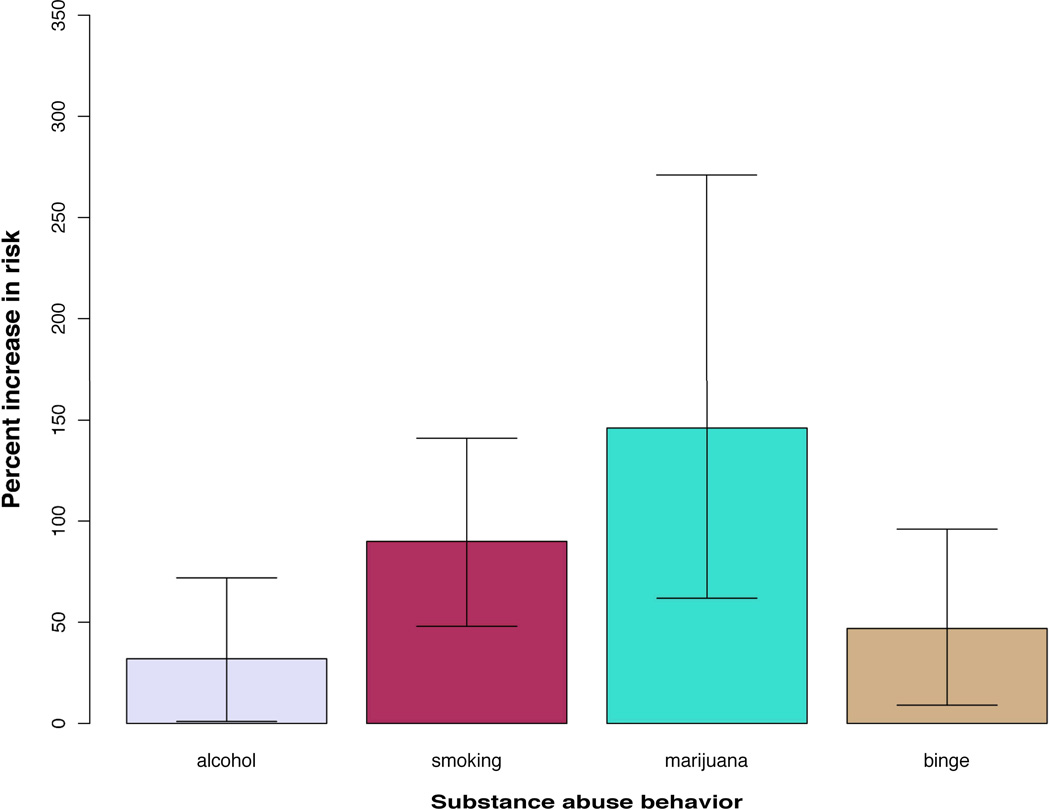

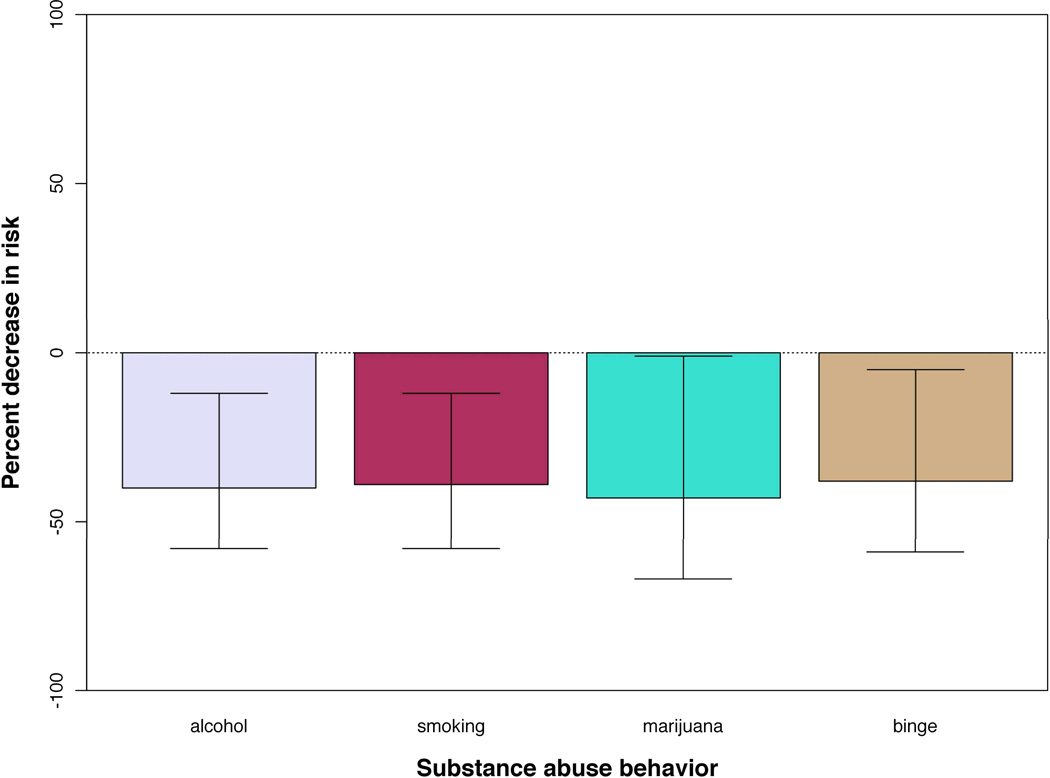

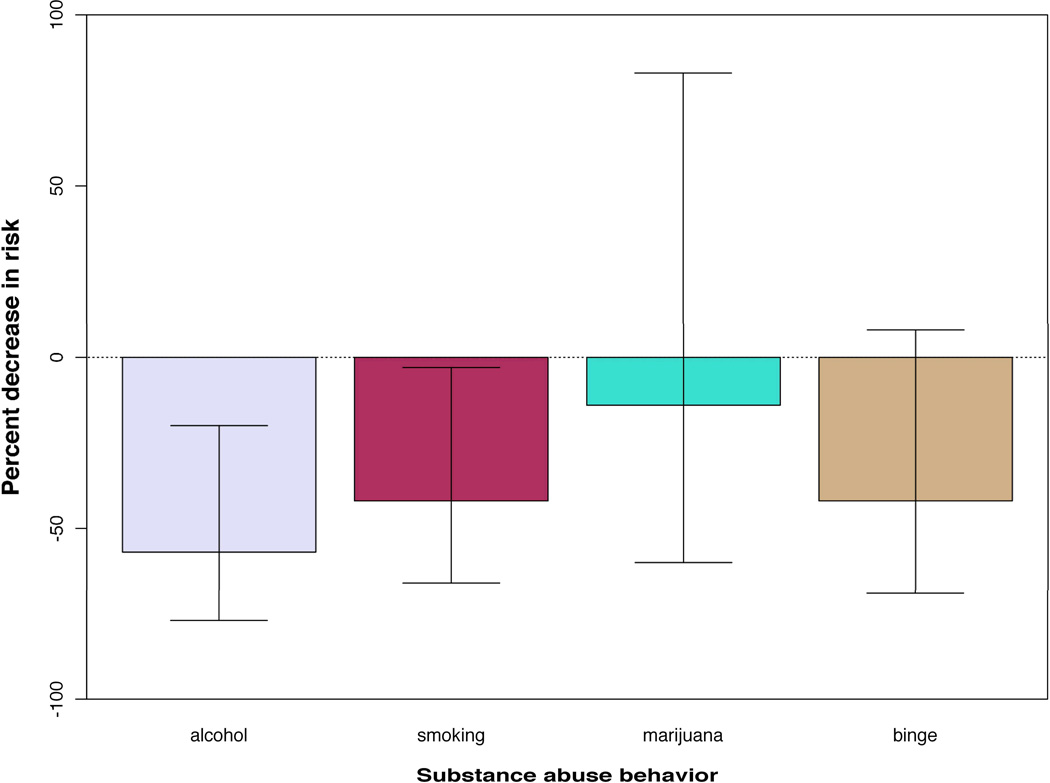

The GEE regression models in the tables presented in the main text and OSA provide parameter estimates in the form of beta coefficients, whereas the results reported in the text and in Figures 2–4 are in the form of risk ratios. The key coefficient in these models that measures the effect of influence is on the variable for friend’s mother’s Wave II parenting style. Risk ratios were calculated from predicted probabilities of substance abuse as a function of parenting style (changing it from 0 to 1) with 95 % confidence intervals estimated using 1.96 plus or minus the se and assuming all other variables are held at their means.

Figure 2.

Percent increase in risk (includes 95% CI) of abusing alcohol, smoking, using marijuana, and binge drinking for an adolescent whose peer engages in the same behavior. All probabilities are estimated controlling for respondent age, gender, race, mother’s education, mother’s income, Wave I substance abuse, parent’s Wave I and Wave II parenting style, friend’s Wave I substance abuse, friend’s parent’s Wave I and Wave II parenting style, plus school level fixed effects.

Figure 4.

Percent decrease in risk (includes 95% CI) of abusing alcohol, smoking, using marijuana or binge drinking for adolescents whose peers’ parents are authoritative versus adolescents whose peers’ parents are neglectful. All probabilities are estimated controlling for respondent age, gender, race, mother’s education, mother’s income, Wave I substance abuse, parent’s Wave I and Wave II parenting style, friend’s Wave I substance abuse, friend’s parent’s Wave I parenting style, plus school level fixed effects.

Results

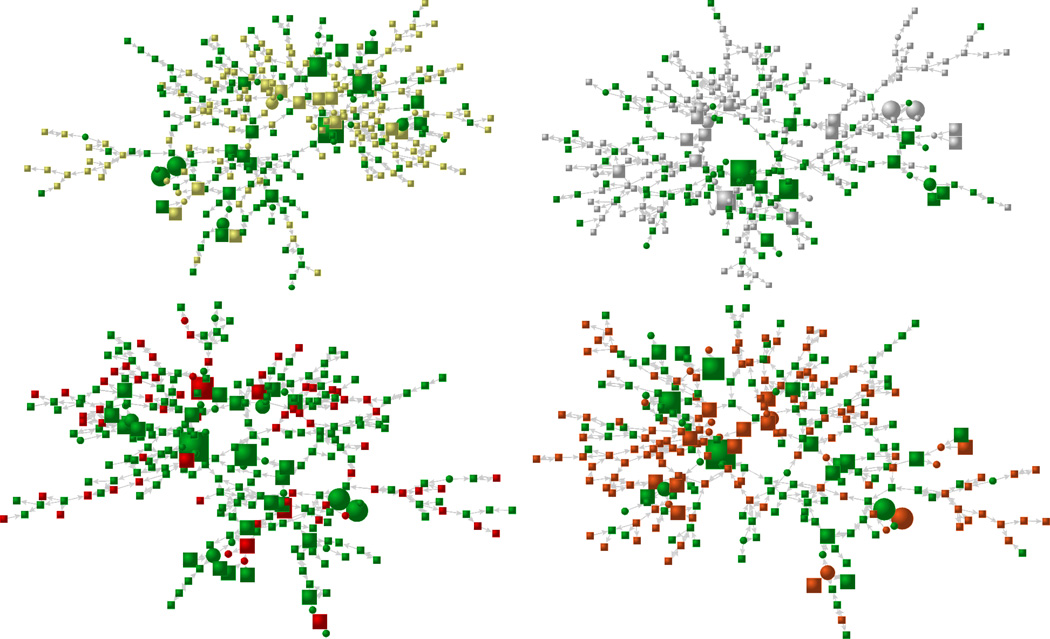

In Figure 1, we show social network graphs that include parenting styles and substance abuse behaviors. These figures illustrate that behavior tends to cluster in the social network, and that adolescents who do not engage in substance abuse are often connected to authoritative parents via their friends, even if their own parents are not authoritative (as evidenced by the large green squares in the figure).

Figure 1.

Illustrative network maps of one school in Add Health (N=304). Each node represents an adolescent and each arrow between them a friendship nomination. Node color indicates substance use behavior, yellow for drinking alcohol (upper left), gray for smoking tobacco (upper right), red for smoking marijuana (lower left), and orange for binge drinking (lower right). Green nodes indicate adolescents who do not engage in the substance abuse behavior shown in that panel. Circle nodes are adolescents with an authoritative parent, and square nodes are those with some other type (neglectful, authoritarian, or permissive). The size of each node is proportional to the number of friend’s parents who are authoritative. These figures show that behavior tends to cluster in the social network, and adolescents who do not engage in substance abuse are often connected to authoritative parents via their friends, even if their own parents are not authoritative (indicated by large green squares).

Statistically, we first studied the relationship between an adolescent’s behavior and their friend’s behavior, controlling for the parenting style of the adolescent’s parent and the adolescent’s friend’s parent, plus fixed effects and demographics (figure 2). The behavior of an adolescent’s friend is significantly associated with the behavior of the adolescent, such that having a friend who drinks to the point of drunkenness increases the probability of the adolescent doing the same by 32% (95% C.I. 1%–72%), having a friend who is a smoker increases the probability of the adolescent smoking by 90% (95% C.I. 48%–141%), having a friend who smokes marijuana increases the probability of an adolescent smoking marijuana by 146% (95% C.I. 62%–271%), and having a friend who is a binge drinker increases the probability of adolescent binge drinking by 47% (95% C.I. 9%–96%). (These estimates are net of the baselines behavior of both parties.) Etables 1–4 (OSA) show the results of all the analyses for all 4 outcomes, where the beta coefficient on the row for friends Wave II substance abuse shows the relevant result.

We then looked at the direct effects of an adolescent’s mother’s parenting style on the adolescent’s behavior, controlling for the adolescent’s friend’s mother’s parenting style (figure 3). If an adolescent has an authoritative parent, the probability of drinking to the point of drunkenness is reduced by 57% (95% C.I. 20%–77%) and the probability of smoking is reduced by 43% (95% C.I. 3%–66%). These results are presented in Table 3 for variable “Own mother authoritarian Wave II” for all 4 outcomes.

Figure 3.

Percent decrease in risk (includes 95% CI) of abusing alcohol, smoking, using marijuana or binge drinking for adolescents whose parents are authoritative versus adolescents who parents are neglectful. All probabilities are estimated controlling for respondent age, gender, race, mother’s education, mother’s income, Wave I substance abuse, parent’s Wave I parenting style, friend’s Wave I substance abuse, friend’s parent’s Wave I and Wave II parenting style, plus school level fixed effects.

Table 3.

Multivariate association between friend's mother's parenting styleand adolescent risk behavior*

| Binge drinking in last yeara N=2056 |

Smoked in last monthb N=2033 |

Was drunk in last yearc N=2061 |

Used marijuana in last monthd N=2003 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% C.I. | P value | RR | 95% C.I. | P value | RR | 95% C.I. | P value | RR | 95% C.I.. | P value | |

| Friend mother permissive Wave II | 0.82 | (0.6–1.11) | 0.20 | 0.87 | (0.66–1.14) | 0.31 | 0.8 | (0.58–1.09) | 0.52 | 0.87 | (0.59–1.3) | 0.51 |

| Friend mother authoritarian Wave II | 0.66 | (0.46–0.94) | 0.02 | 0.84 | (0.61–1.16) | 0.29 | 0.82 | (0.56–1.19) | 0.16 | 1.12 | (0.72–1.72) | 0.62 |

| Friend mother authoritative Wave II | 0.62 | (0.41–0.95) | 0.03 | 0.61 | (0.42–0.88) | 0.01 | 0.6 | (0.41–0.89) | 0.30 | 0.57 | (0.33–0.99) | 0.05 |

| Friend mother permissive Wave I | 1.25 | (0.87–1.81) | 0.23 | 1.17 | (0.84–1.61) | 0.34 | 1.27 | (0.89–1.81) | 0.01 | 1.01 | (0.63–1.63) | 0.96 |

| Friend mother authoritarian Wave I | 0.92 | (0.63–1.36) | 0.68 | 1.14 | (0.81–1.56) | 0.45 | 0.93 | (0.63–1.36) | 0.19 | 0.95 | (0.59–1.51) | 0.82 |

| Friend mother authoritative Wave I | 1.03 | (0.69–1.54) | 0.88 | 1.43 | (1.03–1.95) | 0.03 | 0.92 | (0.62–1.36) | 0.70 | 1.05 | (0.63–1.76) | 0.84 |

| Own mother permissive Wave II | 0.7 | (0.44–1.13) | 0.15 | 0.49 | (0.32–0.75) | 0.00 | 0.72 | (0.46–1.11) | 0.69 | 0.55 | (0.3–1) | 0.05 |

| Own mother authoritarian Wave II | 0.72 | (0.43–1.19) | 0.20 | 1.06 | (0.68–1.62) | 0.80 | 0.56 | (0.34–0.92) | 0.14 | 0.87 | (0.45–1.67) | 0.67 |

| Own mother authoritative Wave II | 0.58 | (0.31–1.08) | 0.09 | 0.58 | (0.34–0.97) | 0.04 | 0.43 | (0.23–0.8) | 0.02 | 0.86 | (0.4–1.83) | 0.69 |

| Own mother permissive Wave I | 0.89 | (0.53–1.48) | 0.65 | 0.87 | (0.54–1.37) | 0.55 | 0.88 | (0.55–1.42) | 0.01 | 1.49 | (0.75–2.97) | 0.25 |

| Own mother authoritarian Wave I | 0.62 | (0.37–1.02) | 0.06 | 0.94 | (0.6–1.44) | 0.78 | 0.84 | (0.52–1.37) | 0.61 | 1.93 | (0.96–3.89) | 0.07 |

| Own mother authoritative Wave I | 0.6 | (0.34–1.06) | 0.08 | 1.31 | (0.81–2.06) | 0.26 | 0.58 | (0.34–0.99) | 0.49 | 1.32 | (0.63–2.76) | 0.46 |

| Friend use Wave 1 | 1.7 | (1.29–2.25) | 0.00 | 1.53 | (1.17–1.97) | 0.00 | 1.81 | (1.38–2.38) | 0.04 | 2.92 | (1.94–4.38) | 0.00 |

| Own use Wave 1 | 7.53 | (5.17–10.88) | 0.00 | 6.77 | (5.33–8.27) | 0.00 | 7.33 | (5.17–10.26) | 0.00 | 11.14 | (6.5–19.08) | 0.00 |

| Deviance | 287.04 | 307.82 | 285.26 | 181.49 | ||||||||

| Null Deviance | 427.8 | 449.19 | 427.81 | 232.14 | ||||||||

reference is neglectful

Consumed 5 or more drinks in a row at one time within last year

Smoked cigarettes at least once in last month

Been drunk or high on alcohol at least once in last year.

Smoked or used marijuana at least once in last month

All models runcontrolling for respondent age, gender, race, mother’s education, mother’s incomeplus school level fixed effects.

Finally, we tested the hypothesized network effect of the mother of an adolescent’s friend (figure 4). If an adolescent has a friend whose mother is authoritative, that adolescent is 40% (95% CI 12%–58%) less likely to drink to the point of drunkenness, 38% (95% CI 5%–59%) less likely to binge drink, 39% (95% CI 12%–58%) less likely to smoke cigarettes, and 43% (95% CI 1%–67%) less likely to use marijuana than an adolescent whose friend’s mother uses authoritative parenting, controlling for the parenting style of the adolescent’s own mother, school level fixed effects, and demographics. Furthermore, if an adolescent has a friend whose mother is authoritarian, that adolescent is 46% (95% CI 6%–54%) less likely to use marijuana than an adolescent who friend’s mother is neglectful. These results are presented in Etables 1–4 (OSA) and the variable of interest is: Friend mother authoritative Wave II. Surprisingly, the strength of association with the parenting style of an adolescent’s friend’s mother is of about the same magnitude as the association with the parenting style of the adolescent’s own mother for alcohol abuse and smoking (the Wald test of differences between coefficient for own mother and friend’s mother with significance at p<=.05 was insignificant in both cases), while the association is stronger for friend’s mothers than own mother for marijuana smoking and binge drinking.

We conducted a mediation analysis (Etables 1–4 OSA) to explore whether parents may have a direct effect on their children’s friends, or if this effect is indirect, resulting from the direct effect on their own children, which then spreads through the adolescent social network. The results suggest that 7.7% of the association between friend’s mother’s authoritative parenting and an adolescent’s alcohol abuse behavior may be explained by the influence that the friend’s mother may have on the friend’s behavior which in turn may influence the adolescent’s behavior. This proportion is 8.9% for marijuana use, and 7.0% for binge drinking. The results of the mediation analysis were insignificant for smoking behavior. In all cases, the association of the friend’s mother’s parenting style with the friend’s behavior was significant, as was the association between the friend’s behavior and the adolescent’s behavior. Furthermore, as can be seen in the last three columns of each table, adding friend’s behavior to the model significantly reduced the association between the friend’s mother’s parenting and the adolescent’s behavior. Sobel tests were significant in all cases, with the exception of alcohol abuse (which at 1.80 is only slightly below the 1.96 level required for significance). Hence, in all cases, the majority of the effect of peer’s parents is direct.

Discussion

Most research on social networks focuses on social influence in direct relationships. In other words, when considering adolescent behavior, we tend to focus on their peers and parents, assuming that influence spreads only from peer to peer or from family member to family member. We have discounted less obvious social influences, or pathways that bridge more heterogeneous dimensions of an adolescent’s social network.

This study used longitudinal complete network data to show a positive correlation between the parenting practices of an adolescent’s friends’ parents, and the substance abuse outcomes of that adolescent. Our analyses demonstrate that if an adolescent has friends whose parents use “authoritative parenting”, that adolescent is less likely to abuse alcohol, smoke, use marijuana, and binge drink. Our results are consistent with previous research that shows the influence of both peers and parents on adolescent substance abuse outcomes, although in this study we find that the indirect influence of a peer’s parents may be just as important, if not more so. Furthermore, our results show that while the pathway between a friend’s parent and an adolescent is partially mediated through the behavior of the peer, this accounts for only a small proportion of the observed relationship.

A large body of literature has supported the idea that peers influence adolescent substance abuse mainly through the modeling of behavior, social norms around substance use, and overt offers to participate in the behavior25,26. However, results of a study by De Vries and colleagues27,28 challenge the peer influence paradigm, suggesting that similarity in smoking behavior among adolescents is likely a function of friendship selection, and that parental smoking behavior is both a stronger predictor of smoking adoption than peer influence as well as a significant predictor of choosing smoking peers. Both peer influence and peer selection based upon shared attributes surely occur29–33. Here, we demonstrate that a peer’s engagement in substance abuse is strongly correlated with an increased probability of the adolescent initiating that same behavior. By controlling for endogenous factors, that is the baseline behavior of both the adolescent and his/her peers, we reduce the likelihood that choosing substance-abusing peers is the driving force behind the peer effect we observe in the model.

The influence of a parent, on the other hand, has been studied from the dimension of behavioral modeling28,34 (adolescents with substance abusing parents are more likely to abuse themselves), as well as from the perspective of parenting practices. These are two distinct (though possibly interacting) pathways of influence as the parenting practices of an adolescent’s family appear to promote positive outcomes through the shaping of psychological resilience and emotional well being, rather than simply as the result of modeling specific behaviors35. These practices empower the adolescent to make beneficial choices and engage in positive behavior along a wide variety of dimensions.

The results of our mediation analysis suggest that, to some degree, the influence of the positive parenting of a friend’s mother on an adolescent may be mediated through the behavior of the friend. That is, positive parenting discourages substance abuse in adolescents, which then leads to reduced substance abuse in their friends. However, this is only part of the story. The mediation model did not account for the majority of the observed effect. This suggests that positive parenting may benefit an adolescent’s friendship network either through a buffering effect via the adolescent’s positive psychological outcomes and behaviors and/or a direct contact effect with the friends’ parent. That is, adolescents may have frequent contact with their friends’ parents and may therefore benefit directly from observing the positive parenting interactions that are taking place within those families. A second possibility is that having peers who are psychologically bolstered by good parenting benefits an adolescent through the interactions between them, independent of whether or not those peers are modeling substance abuse behaviors. A third possibility is that an adult who uses positive parenting behaviors with their own adolescent child is also able to act as an effective mentor for that child’s friends. Research on mentoring has identified ways in which unrelated adults can positively influence adolescents along many dimensions 36 partially because as these unrelated adults are external to the normal adolescent-parent conflict14, adolescents may feel freer to express needs and concerns they may not be able to express with their own parents37. Mentoring is most successful when the relationship is long-term, imbued with positive affect, and the mentor is able to offer some sort of instrumental support37,38. Positive relationships with friends’ parents may have multiple advantages consistent with this view of successful mentorship.

This study has limitations. The results may not be generalizable to all adolescents in the United States, as the final network cannot be weighted to be nationally representative. Moreover, self-report substance abuse measures may be subject to bias due to social desirability or inexact recall. However, unlike measures used in many social influence studies, the peer substance abuse measures in this study are not reported as conjecture by the adolescent, but directly reported by the friend regarding their own behavior.

Any association between adolescents’ drug use and their friends’ parents’ parenting style is based on observational data, and as such it is possible that either (1) adolescents are influenced by the neglectfulness of their friends’ parents, and this neglectfulness promotes drug use or (2) parents are influenced by their children’s friends’ drug use, which causes them to become more neglectful.. Darling and colleagues note that adolescents seek out non-parental adult role models37, suggesting that parents affect adolescents and not the other way around, but it is important to stress that the association we report here may be in part due to reciprocal influence.

Conclusion

There is a body of evidence to suggest that offering education on parenting can bolster parenting competence which in turn results in a wide variety of improved outcomes for adolescents39–41. The results of our research suggest that investments in such interventions may pay off not only through the direct connection between parent and child, but through the less obvious direction of parent to child to child’s friends, as well directly from parent to child’s friend. As a consequence, we may be undervaluing the total benefit that parenting education has on adolescent populations.42

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Bivariate association between friend's mother's parenting style (Wave II) and adolescent risk behavior*

| Binge drinking in last yeara | Smoked in last monthb | Was drunk in last yearc | Used marijuana in last monthd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | P value | RR | 95% CI | P value | RR | 95% CI | P value | RR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Friend mother permissive | 0.87 | (0.74–1.02) | 0.09 | 0.93 | (0.79–1.08) | 0.34 | 0.84 | (0.71–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.80 | (0.61–1.05) | 0.11 |

| Friend mother authoritarian | 0.65 | (0.52–0.81) | 0.00 | 0.82 | (0.67–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.7 | (0.56–0.86) | 0.00 | 0.92 | (0.68–1.24) | 0.60 |

| Friend mother authoritative | 0.49 | (0.38–0.64) | 0.00 | 0.64 | (0.5–0.79) | 0.00 | 0.46 | (0.36–0.6) | 0.00 | 0.46 | (0.31–0.68) | 0.00 |

reference is neglectful.

Consumed 5 or more drinks in a row at one time within last year n=2056

Smoked cigarettes at least once in last month n=2033

Been drunk or high on alcohol at least once in last year. n=2061

Smoked or used marijuana at least once in last month n=2003

Abbreviations

- Addhealth

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health

- OSA

Online supplementary Appendix

- GEE

generalized estimating equation

References

- 1.Burt RD, Peterson AV. Smoking cessation among high school seniors. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27(3):319–327. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan CP, Napoles-Springer A, Stewart SL, Perez-Stable EJ. Smoking acquisition among adolescents and young Latinas:: The role of socioenvironmental and personal factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(4):531–550. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen PH, White HR, Pandina RJ. Predictors of smoking cessation from adolescence into young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(4):517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21(4):349. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urberg KA, Defüirmencio fülu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Dev Psychol. 1997;33(5):834. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(21):2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenquist J, Murabito J, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152(7):426. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mednick SC, Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of sleep loss influences drug use in adolescent social networks. PloS one. 2010;5(3):e9775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyler KA. Social network characteristics and risky sexual and drug related behaviors among homeless young adults. Social Science Research. 2008;37(2):673–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mundt MP. The Impact of Peer Social Networks on Adolescent Alcohol Use Initiation. Academic Pediatrics. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latkin CA, Hua W, Tobin K. Social network correlates of self-reported non-fatal overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4(1p2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Handbook of Child Psychology. 1983;4:1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demuth S, Brown SL. Family structure, family processes, and adolescent delinquency: The significance of parental absence versus parental gender. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2004;41(1):58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg L, Elmen JD, Mounts NS. Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Dev. 1989:1424–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray MR, Steinberg L. Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. J Marriage Fam. 1999 Aug;61(3):574–587. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP. Parenting style, religiosity, peers, and adolescent heavy drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71(4):539. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Driscoll AK, Russell ST, Crockett LJ. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(2):185–209. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knoester C, Haynie DL, Stephens CM. Parenting practices and adolescents' friendship networks. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(5):1247–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher AC, Darling DE, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM. The company they keep - relation of adolescents adjustment and behavior to their friends perceptions of authoritative parenting in the social network. Dev Psychol. 1995 Mar;31(2):300–310. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM. Over time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1994;65(3):754–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator, Äìmediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):19. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance abuse. 2001;13(4):391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vries H, Candel M, Engels R, Mercken L. Challenges to the peer influence paradigm: results for 12–13 year olds from six European countries from the European Smoking Prevention Framework Approach study. Tob Control. 2006;15(2):83. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.007237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, Feighner JA. Patterns of alcohol and drug use in adolescents can be predicted by parental substance use disorders. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):792. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall JA, Valente T. Adolescent smoking networks: The effects of influence and selection on future smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3054–3059. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger JB, Valente T. Peer influences on adolescent cigarette smoking: A theoretical review of the literature. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(1):103–155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valente T. Social network influences on adolescent substance use: An introduction. Connections. 2003;25(2):11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaughan M. Predisposition and pressure: Mutual influence and adolescent drunkenness. Connections. 2003;25(2):17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social Contagion Theory: Examining Dynamic Social Networks and Human Behavior. Statistics in Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1002/sim.5408. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfistera RLASH, Wittchena HU. Maternal smoking and smoking in adolescents: a prospective community study of adolescents and their mothers. Eur Addict Res. 2003;9:120–130. doi: 10.1159/000070980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins WA, Maccoby EE, Steinberg L, Hetherington EM, Bornstein MH. Contemporary research on parenting - The case for nature and nurture. Am Psychol. 2000 Feb;55(2):218–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DuBois DL, Silverthorn N. Characteristics of natural mentoring relationships and adolescent adjustment: Evidence from a national study. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26(2):69–92. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-1832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darling N, Hamilton SF, Shaver KH. Relationships outside the family: Unrelated adults. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. 2003:349–370. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darling N, Hamilton SF, Niego S. Adolescents' relations with adults outside the family. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. An efficacious theory-based intervention for stepfamilies*. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(4):357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Woody RH. Intervening in Children's Lives: An Ecological, Family-Centered Approach to Mental Health Care. Adolescence. 2008;43(169):185. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stormshak EA, Connell AM, Véronneau MH, et al. An ecological approach to promoting early adolescent mental health and social adaptation: family-centered intervention in public middle schools. Child Dev. 2011;82(1):209–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christakis NA. Social networks and collateral health effects. BMJ. 2004;329(7459):184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7459.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.