Abstract

Fmlns belong to the Formin family, catalysts of linear Actin polymerization with mostly unknown roles in vivo. In cell culture Fmnls are involved in cell migration and adhesion and the formation of different types of protrusions including filopodia and blebs, suggesting important roles during development. Moreover, Fmnls can act downstream of Rac and Cdc42, mediators of cytoskeletal changes as targets of important pathways required for shaping tissues. The zebrafish genome encodes five Fmnls. Here we report their tissue specific expression patterns during early development and pharyngula stages. The fmnls show overlapping and distinct expression patterns, which suggest that they could regulate similar processes during development, but may also have independent functions. In particular, we find a strong maternal contribution of all fmnls, but distinct expression patterns in the developing brain eye, ear, heart and vascular system.

Keywords: Actin, vascular system, visual system, otic vesicles, brain

1-Results and discussion

During embryogenesis, tissues are shaped by complex cellular interactions and movements to ensure organ primordia are properly specified and positioned (1). The underlying complex movement of tissues requires precise coordination of signals with individual cell behaviors in part through modulation of the Actin cytoskeleton. Actin nucleation is a key event in the assembly of long filaments, which are required for many cellular activities including cell division, migration, and polarization (2). Formins are important catalysts of linear Actin polymerization (3). However, the developmental contributions of individual members of this large protein family are not well understood since only a few Formins have been examined.

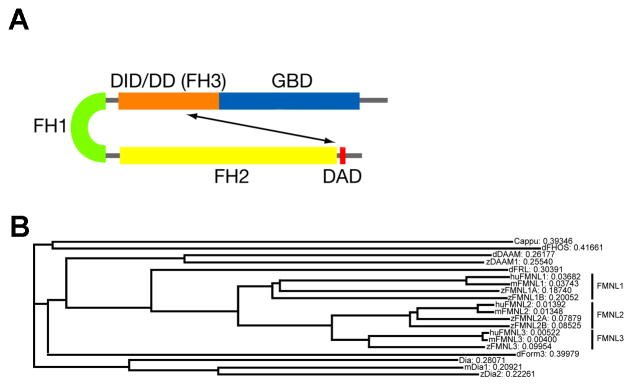

The Formins are subdivided into seven subfamilies that include the founding member, Cappucino, which is crucial for anteroposterior and dorsoventral patterning in Drosophila (4). Other well known members include Diaphanous and the Disheveled-associated activators of morphogenesis (DAAM), the latter of which function as components of the non-canonical Wnt/Fz-Planar Cell Polarity (Wnt/PCP) pathway, a major regulator of polarized cell behaviors required for cell migration during morphogenesis (5). All Formins share key structural domains (2, 6) (Fig. 1A), including a FH1 (a Formin homology domain 1 that binds profilin often in complexes with Actin monomers) and the catalytic FH2 domain. Diaphanous related formins (Drf) also contain a Rho-family GTPase binding domain (GBD), a Diaphanous inhibitory domain/Dimerization domain (DID/DD, a.k.a. FH3 domain) and a C-terminal Diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD). The activation mechanism for Formins is not well understood; often, Drfs are auto-inhibited upon binding of the DAD domain to the DID domain (Fig. 1A) (6–8), until the proteins are activated by GTPase binding or phosphorylation of the DAD domain. Formin homo and heterodimers are thought to represent the active form of these proteins (2) as either mediators of Actin nucleation or extension.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic of the protein domains of a typical Fmnl. B) Phylogenetic relationship between the FH2 domain of individual Fmnls in human, mouse, zebrafish and fly as well as selected other formins. The length of the branches represents the degree of change in FH2 domain sequence. DAD: Diaphanous autoregulatory domain; DID/DD: Diaphanous inhibitory domain/Dimerization domain; FH: Formin homology domain; GBD: GTPase binding domain.

A less known Formin subfamily is the Formin-related in Leukocytes (Frl in Drosophila and originally in mice, now more commonly known as Fmnl in vertebrates), which control actin nucleation or polymerization via Rac or Cdc42 regulated mechanisms (9–11). While Drosophila has one frl gene, mammals have three and zebrafish have five. Although Fmnls are composed of the same functional domains as the other Formins, our knowledge of how they contribute to early development remains limited to a recent study reporting a role for Fmnl3 in trunk angiogenesis in zebrafish (12). However, the extent to which individual Fmnls have cell type specific functions or are redundant remains to be determined. To determine whether individual zebrafish fmnls (1a, 1b, 2a, 2b and 3) show temporal or tissue specific expression patterns during early development and morphogenesis, we examined their expression profiles by RT-PCR and in situ hybridization.

Our detailed expression studies will guide future functional work toward understanding the function of Fmnls during development. These studies reveal that fmnls show overlapping expression patterns during early development except fmnl2a (Fig. 3), which becomes distinct from late gastrulation onwards. At later stages, the fmnls are all expressed in the visual, otic and vascular systems, but cell type specific patterns are also apparent (Fig. 4 and 5). For example fmnl1b is detected in the lens, fmnl2a in the central part of the retina, and fmnl3 in the cristae of the otic vesicles (Fig. 4).

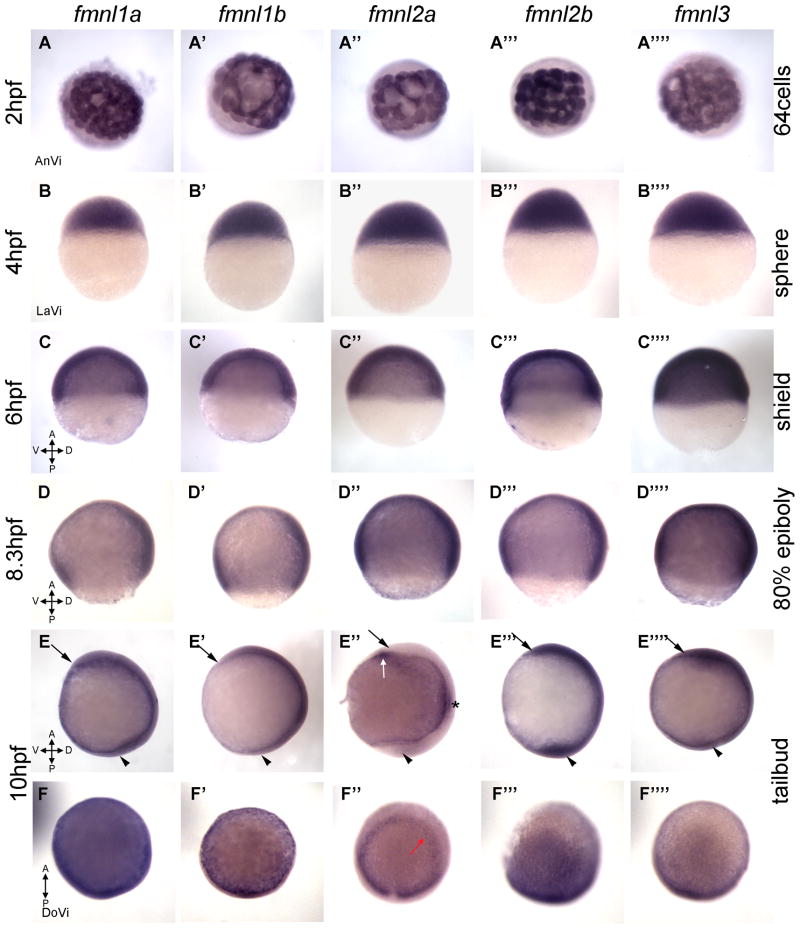

Figure 3.

Expression of fmnl transcripts in blastula and gastrula. (A–B) fmnls are maternally provided (1–4 hpf) and (C–F) expression persists during gastrulation (5–10 hpf). (E,F) Tailbud stage (Tb). The head is indicated by an arrow and the tailbud by an arrowhead. fmnl2a is robustly expressed in the otic vesicle primordia (asterisk in E″), the neuroectoderm border (red arrow in F″) and in the hatching gland (white arrow in 3E″). A: anterior; AnVi: anterior view; D: dorsal; DoVi: dorsal view; LaVi: lateral view; P: posterior; V: ventral.

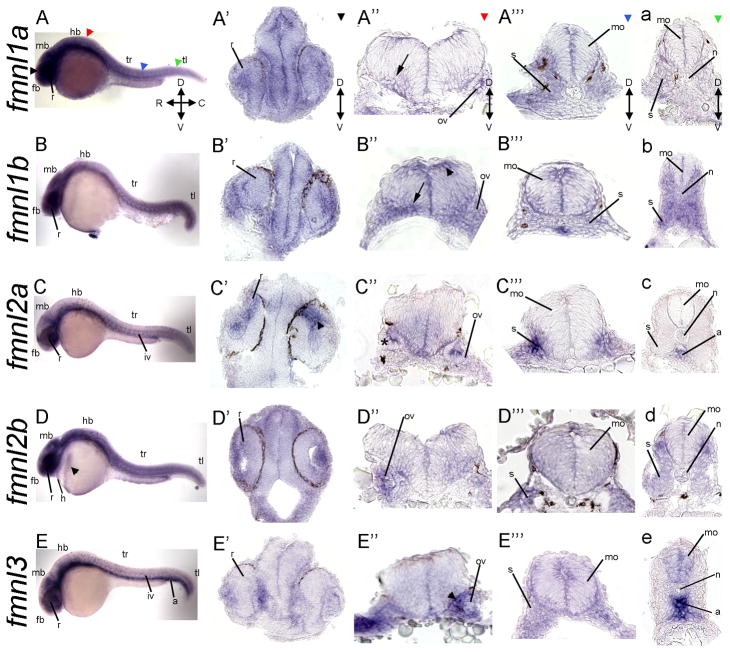

Figure 4.

Expression of fmnls at 24 hpf reveals overlapping and distinct patterns. A–E) Whole mount lateral views. Colored triangles indicate level of cross sections: black indicates forebrain (fb; A′–E′), red the level of the hindbrain (hb; A″–E″), blue the sections through the trunk (tr; A‴–E‴), and green the sections through the tail (tl; a–e). fmnl1a and fmnl1b are expressed in the ventral hindbrain in a fibrous-like pattern (arrows in A″ and B″). fmnl1b is expressed in the dorsal hindbrain (arrowhead in B″); fmnl2a in the dorsal retina (r) (arrowhead in C′), otic vesicle (ov) (asterisk in C″) and somites; fmnl2b in the hatching gland (arrowhead in D), the heart (h) and the lens and fmnl3 in the aorta (a), the ov (arrowhead in E″) and somites (s). Orientation is conserved for all the whole mount and section images. C: caudal; D: dorsal; mb: midbrain; mo: medulla oblongata; n: notochord; iv: intersomitic vessels; R: rostral; V: ventral.

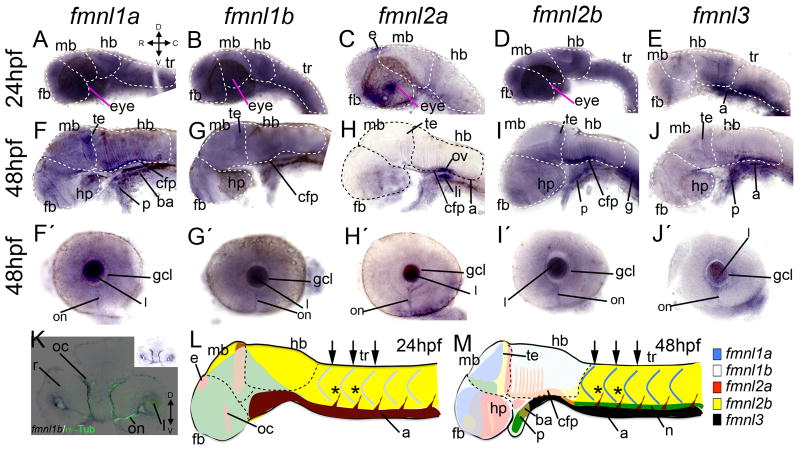

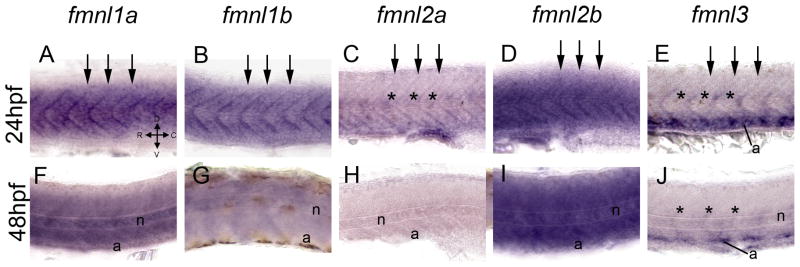

Figure 5.

Expression of fmnls in the trunk of larvae at 24 (A–E) and 48 (F–J) hpf. At 24 hpf fmnls were robust in the myotome boundaries (arrows) and fmnl2a and 3 were also expressed in the intersomitic vessels (asterisks) and fmnl3 in the aorta (a) (E). At 48 hpf fmnl1a, 1b and 2b were robust in the notochord (n) (F, G, I) and fmnl3 is still present in the aorta and the intersomitic vessels (asterisks in J).

1.1 Zebrafish fmnls and their phylogenetic relationships with other formins

As mentioned, flies possess a single frl (13), mammals have three distinct fmnls (14) and zebrafish have five fmnl genes. To clarify the relationship between individual Formins of human, mouse, fly and fish, we have compared the protein sequence of the FH2 domain, which is the defining domain of the Formin superfamily (6). Fmnls of each species are phylogenetically related and cluster together in the phylogram as a single subbranch that includes Drosophila frl, but no ‘non-Fmnl’ Formins (Fig. 1B), such as Cappuccino, Diaphanous, or DAAM. A similar relationship was observed when we compared the full coding sequence (data not shown).

As zebrafish fmnls have received different names depending on whether the human (fmnl) or early mouse (frl) nomenclature was used, we have summarized the accession numbers and the names of fmnls in humans, mice, and zebrafish in Table 1. Based on sequence comparison and phylogenetic analyses zebrafish have a single fml3 gene and duplicated fmnl1 and fmnl2 genes, (Table 1, Fig 1B, Zebrafish Genome Project Assembly ZV7, Wellcome trust Sanger Institute).

Table 1.

Summary of zebrafish fmnls and their homologs in human and mouse. In flies there is only one Frl.

| Zebrafish name | Zebrafish Chromosome | Other names | Zebrafish Ensembl ID | Human name | Human Ensembl ID | Mouse name | Mouse Ensembl ID | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmnl1a | 3 | zFrl1B/Fmnl 1 (1 of 2) | ENSDARG00000055713 | Fmnl1 | ENSG00000184922 | Fmnl1 | ENSMUSG00000055805 | (14, 24) |

| Fmnl1b | 24 | zFrl1A/Fmnl 1 (2 of 2) | ENSDARG00000075519 | |||||

| Fmnl2a | 9 | zFrl3 | ENSDARG00000012586 | Fmnl2 | ENSG00000157827 | Fmnl2 | ENSMUSG00000036053 | (10, 14) |

| Fmnl2b | 6 | ENSDARG00000075041 | ||||||

| Fmnl3 | 23 | zFrl2 | ENSDARG00000004372 | Fmnl3 | ENSG00000161791 | Fmnl3 | ENSMUSG00000023008 | (11, 12, 14, 23) |

1.2 fmnls show dynamic expression patterns during zebrafish development

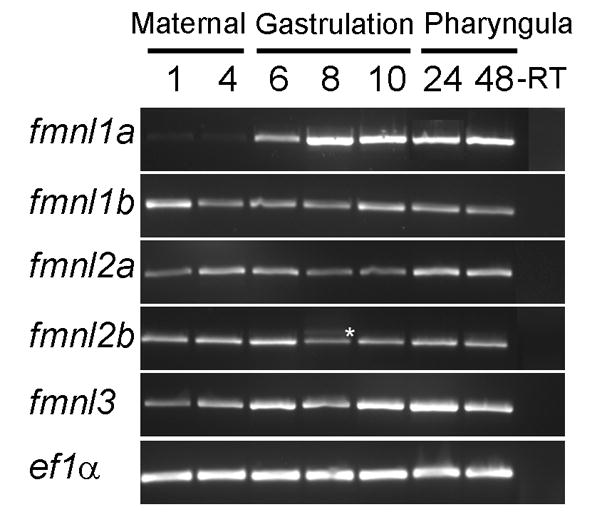

To determine if the five zebrafish fmnls show distinct temporal expression profiles, we used RT-PCR to examine their expression during embryogenesis. The fmnl mRNAs were detected at all stages examined albeit with variable abundance (Fig. 2). Specifically, fmnl1a was maternally expressed and became more abundant in early and late gastrulae (6 and 10 hours postfertilization, hpf), while fmnl1b showed substantial maternal expression, which persisted with a lower abundance thereafter. fmnl2a was expressed maternally and in early gastrulae and was more abundant later in morphogenesis, while fmnl2b expression was highly expressed during maternal stages and persisted throughout gastrulation and larval stages. Intriguingly, at mid-gastrula (8 hpf) a second splice variant of fmnl2b was detected. This variant of fmnl2b includes an additional exon in between exon 11 and exon 12 that was not amplified from no-RT controls (Fig. 2; see sequence in methods). fmnl3 was expressed in blastulae (1 and 4 hpf) when only maternal transcripts are present and became more abundant in late gastrulae and larvae (10, 24, 48 hpf).

Figure 2.

Temporal analysis of zebrafish fmnls using RT-PCR.* indicates alternative splice variant of fmnl2b detected in mid-gastrula stage embryos. This variant includes an additional exon between exons 11 and 12.

Several functions have been attributed to Fmnls such as cell migration and cell adhesion (15), important phenomena during early development. Our results suggest that all zebrafish fmnls are expressed throughout early development and morphogenesis. Although temporal analysis alone did not reveal or exclude distinct functions of fmnls, they could be divided based on peaks in their expression profiles: fmnl1b is uniformly abundant, fmnl2b appears most abundant during maternal stages and pharyngula stages, fmnl1a is low at maternal stages, is more abundant in gastrula, and thereafter is highly expressed through pharyngula stages. fmnl2a and fmnl3 are maternally expressed and appear most abundant during pharyngula stages of morphogenesis.

1.3 fmnls are ubiquitously expressed during early development and gastrulation

Our RT-PCR analysis indicates that the fmnls are expressed throughout embryogenesis. However, some Formin family members are known to be expressed in a discrete subset of tissues, such as FMN, which is expressed in the developing nervous system and kidneys of mammals (15–17) and in the oocytes of Drosophila (4). To investigate whether zebrafish fmnls also show tissue specific expression patterns we generated ribo-probes and analyzed the distribution of fmnl mRNAs at several developmental stages. All fmnls were maternally provided and showed similar ubiquitous patterns at stages when the zebrafish embryo undergoes extensive actin remodeling and rapid cell divisions (Fig. 3A,B). Another Formin, Dia, has been shown to contribute to mitosis through Actin dependent (18) and independent (19) mechanisms. During late blastula and early gastrulation (6–10hpf; Fig. 3C–F), fmnls remained ubiquitously expressed during stages when cell adhesion and coordinated polarized cell behaviors contribute to organization of the embryonic body plan (20, 21). The first detectable difference between expression patterns of the individual fmnls was observed at tailbud stage when fmnl2a expression becomes prominent in the otic primordium (asterisks in Fig. 3E″), in the neuroectoderm border (red arrow in the dorsal view in Fig. 3F″) in a pattern reminiscent of dlx3 expression, and in the hatching gland (white arrow in Fig. 3E″). This unique expression pattern might reflect a more significant role for fmnl2a in these tissues of the late gastrulae.

The robust expression of fmnls during gastrulation is consistent with putative roles for Fmnls in regulating cell migration in vivo. For example, The balance between Actin-based protrusions (e.g. filopodia) and other protrusions (e.g. blebs) is important for proper gastrulation and when disrupted leads to cell migration defects (22). Consistent with this notion, Fmnl3 has been described to be involved in the formation of filopodia (23), Fmnl1 has been implicated in polarized membrane blebbing (24), and Fmnl2 has been shown to drive Actin-based protrusions downstream of Cdc42 in cell culture (10). Although the fmnl RNAs are widely expressed, we cannot exclude the possibility that individual Fmnls proteins show more restricted localization or activation to fulfill tissue specific functions.

1.4 Overlapping and distinct expression patterns of fmnls during pharyngula stages

Morphogenesis of the embryonic body plan and organ primordia continues after gastrulation; therefore, we conducted whole mount in situ staining to investigate whether zebrafish fmnls show distinct expression patterns during pharyngula stages (24 and 48 hpf). Although fmnl1a, 1b, 2b were more widely expressed, all fmlns partially overlapped in their expression patterns (Fig. 4–E; Fig. 7L, M). At 24 hpf, all the fmnls were more prominently expressed in anterior regions of the embryo. Specifically, common domains of enhanced expression included the vitreal region of the retina (Fig 4A–E and A′–E′), which gives rise to the ganglion cell layer at later stages, and the lens, except for fmnl3 (Fig. 7A–D). Furthermore, some fmnls showed distinct expression patterns within the retina. fmnl2a expression was more pronounced in the dorsal region of the retina compared to the vitreal region (arrowhead in Fig. 4C′). Within the forebrain, fmnl2a was robust in the epiphysis (Fig. 7C). All the fmnls were enriched in a fibrous-like pattern within the cephalic floor plate of the hindbrain (Fig. 4A′–E), but fmnl1b was also highly expressed in the dorsal hindbrain (arrowhead in Fig. 4B″). At this early pharyngula stage, consistent with chicken FMN1 expression (25), fmnl1a, fmnl2a, fmnl2b, and fmnl3 were strongly expressed in distinct regions of the otic vesicle (asterisk in Fig. 4C″, arrowhead in Fig. 4E″). Tissue specific expression of fmnl2a and fmnl3 within the retina and the otic vesicles is consistent with the possibility that fmnls differentially contribute to certain processes, including lens and otic vesicle development.

Figure 7.

Expression of fmnls in the anterior part of the larvae. At 24 hpf, fmnl1a, 1b and 2b are widely expressed (A, B, D). fmnl2a is robust in the eye and in the epiphysis (e) (C). fmnl3 show enhanced expression in the posterior part of the hindbrain (hb) an in the aorta (a) (E). At 48 hpf, fmnl1a, 1b and 2b are enhanced in the posterior part of the midbrain (mb) and the floor pate (fp) of the hb. fmnl2a and 3 are also expressed in the floor plate. fmnl1a, 2b and 3 are expressed in the heart (F, G, J) and all fmnls are expressed in the optic nerve (on) (F′–J′), this staining colocalized with α-Tubulin (K for fmnl1b). In L and M, a summary of the expression pattern of all fmnls is shown (not all the domains are represented). C: caudal; D: dorsal; fb: forebrain; h: heart; hp; hypothalamus; l: lens; R: rostral; r: retina; oc: optic commissure; tr: trunk; V: ventral.

fmnls were detected within the trunk and the tail regions of the embryo (Fig. 4A‴–E‴ and a–e) with fmnl1a, fmnl2a and 3 displaying more pronounced expression in more rostral regions (Fig. 4A‴, 4C‴ and 4E‴) and fmnl1b, and 2b more robust in caudal somites (Fig. 4b, 4d). All fmnls were robust along the myotome boundaries (arrows in Fig. 5A–E). fmnl2b was also abundant in the hatching gland (arrowhead in Fig. 4D), and also is present in the heart. Expression of fmnl2a and 3 was robust in the intersegmental vessels (asterisks in Fig. 5C, E), in the ventral aorta (Fig. 4c, e and 5E) and fmnl3 in other vessels within the head of the embryo (Fig. 7E). Consistent with the expression pattern of fmnl3, we and others have observed a role for fmnl3 in zebrafish angiogenesis via morpholino mediated interference (12) (and A.S-L., A.J. and F.L.M. unpublished). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the other fmnls will also have nonredundant tissue specific requirements. For example, fmnl2b might play a specific role in heart development like the closely related Formin, DAAM1, which modulates cytoskeletal function in cardiomyocytes of the mouse via a RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42 dependent mechanism (26).

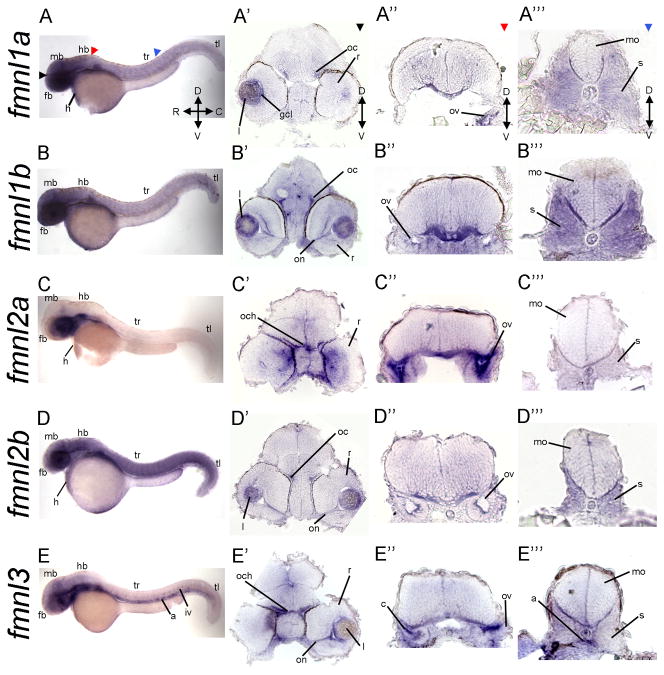

At 48 hpf, fmnl expression patterns become more refined, particularly within the brain (Fig. 7M). fmnl1a, 1b and 2b remain widely expressed with strong expression in the head (Fig. 6A, B and D; Fig. 7F, G and I). While all are expressed in the optic nerve of the retina (Fig. 7F′–J′), fmnl1b and fmnl3 appear more robustly expressed there (Fig. 6B′ and E′), which might reflect a role in axon pathfinding or outgrowth. In support of this notion, fmnl1b colocalizes with α–Tubulin (Fig. 7K). fmnl expression in the visual system is not limited to the optic nerve, as fmnls are also expressed in the optic commissures (fmnl1a, 1b and 2b; Fig. 6A′–C′), the optic chiasm (fmnl2a; Fig. 6C′ and fmnl3; Fig. 6E′) or the ganglion cell layer (fmnl1a; Fig. 7F′ and fmnl3; Fig. 7J′). Interestingly, fmnl2a was distinctly expressed within the central part of the outer most layer of the retina (Fig. 6C′), the region undergoing cell differentiation at this stage. fmnls are also very robust in the optic tectum (Fig. 7F, G, I, J). These patterns are consistent with potential dedicated functions of fmnls to specific aspects of visual development, including retinal and tectum differentiation.

Figure 6.

Expression of fmnls at 48 hpf reveals more distinct patterns than at earlier stages. A–E) Lateral views of whole-mount embryos. Colored triangles indicate level of cross sections: black indicates forebrain (fb; A′–E′), red the level of the hindbrain (hb; A″–E″), and blue the sections through the trunk (tr; A‴–E‴). Colored arrowheads indicate the level cross sections in A′–E′) black arrows indicate forebrain (fb), A″–E″) at the level of the hindbrain (hb) red arrowhead and A‴–E‴) blue arrowhead indicating sections through the trunk (tr). fmnl1a, 1b and 2a are enriched in the head (A, B, D). fmnl1a and 1b are robust in somites (A‴ and B‴). fmnl1b, 2b and 3 are highly expressed in the visual system including the optic commissure (oc), optic nerve (on) and lens (l) (B′, D′, E′). fmnl2a is expressed in the medial region of the retina (C′). Within the otic vesicle (ov), fmnl2a is broadly expressed (C″), while (E″) fmnl3 has more prominent expression in the cristae (c). a: aorta; C: caudal; gcl: ganglion cell layer; D: dorsal; mb: midbrain; mo: medulla oblongata; n: notochord; och: optic chiasm r: retina iv: intersomitic vessels; R: rostral; r: retina; tl: tail; V: ventral.

In the posterior brain of the pharyngula, we observed common domains of expression within the basal plate of the hindbrain and the otic vesicle (Fig 6A″–E″ and Fig 7F–J). However, as within the eye, fmnl expression within the otic vesicle was not completely overlapping. For example, fmnl2a was most prominently expressed within the otic vesicle (Fig. 6C″; Fig. 7H) while fmnl3 was more robust in the cristae (Fig. 6E″), actin-rich structures within the developing ear (27). Other structures in the anterior part of the embryos that also present fmnls expression are the branchial arches (fmnl1a; Fig. 7F), the pharynx (fmnl1a; Fig. 7F; fmnl2b; Fig. 7I and Fmnl3; Fig. 7J), the liver (fmnl2a; Fig. 7H), and the gut (fmnl3; Fig. 7J).

In the trunk only fmnl1a, 1b, 2b and 3 (Fig. 5F, G, I, J; Fig. 6A‴, B‴, D‴, E‴), but not fmnl2a (Fig. 5H and Fig. 6C and C‴) were expressed, although fmnl2b expression pattern was very diffuse (Fig. 5I) fmnl3 was also detected in the aorta and the vascular system of the head (Fig. 6E and 6E‴ and Fig 7J). fmnl1a and 2b were also expressed in the heart (Fig. 6). At this stage, among the fmnls, fmnl1b was most prominent in the somites (Fig. 6B‴).

Our expression analysis and the recent report demonstrating an endothelial cell development defect in fmnl3 morphants (12) suggest that the zebrafish fmnls play an important role during vertebrate development. Moreover, the overlapping and distinct expression patterns throughout development described here point to redundant as well as specific functions of the different fmnls. Future work is required to elucidate the extent of this redundancy and the individual contributions of each Fmnl to the development of structures such as the otic and optic vesicles, the optic nerve projections, the optic commissures, and the developing brain, heart, and vascular system.

2-Experimental Procedures

2.1-Animals

AB strain zebrafish embryos were generated by natural pair-wise mating. They were staged and reared according to standard procedures (28). Specimens were anaesthetized with ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanosulphonate salt (Sigma, St Louis, MO) before they were fixed in paraformaldehyde 4%. The stages used were: maternal stages (2, 4 hpf), gastrulation (6, 8, 10 hpf) and pharyngula (24, 48 hpf).

All procedures and experimental protocols were in accordance to NIH guidelines and approved by the Einstein IACUC under protocol #20100509.

2.2-Phylogram

FASTA protein sequences corresponding to the FH2 domain were obtained from Genbank or the Ensembl website (www.ensembl.org) and analyzed using the Satchmo online software provided by the University of Berkely (http://phylogenomics.berkeley.edu/q/satchmo (30)). Accession or ID numbers are as follows: Capu: NP_722950; dFhos: NP_729410; dDAAM: AAF45601; zDAAM1: XP_707353; dFrl: NP_001137948 (CG32138); huFMNL1: NP_005883; mFmnl1: NP_001071166; zFmnl1a: XP_685133; zFmnl1b: XP_001336442; huFMNL2: NP_443137; mFmnl2: XP_288949; zFmnl2a: XP_001345195; zFmnl2b: XP_002662354; huFMNL3: EAW58086; mFmnl3: XP_128263; zFmnl3: XP_001920583; dFrom3 (Inf): BAC76439; dDia: T13170; mDia1: NP_031884; zDia2:XP_683813.

2.3-RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA synthesis was carried out by reverse transcription using the Applied SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer instructions.

The concentration of cDNA was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm with a Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer and the PCR was performed using the Gotaq Hot Start Polymerase (Promega). The following primers were used:

| fmnl1a | CAGATCCAGGCCTATTTGGA | TCCAGGCTTCCAGAGACTGT |

| fmnl1b | AGAGCGTCCTCATCCTCAAA | CACGAGTGCTGCTTTATCCA |

| fmnl2a | CCAGGACTAAGGCTCTGGTG | CAGAGCTCCGACATCAAACA |

| fmnl2b | CGAGATCATCCTTGCTGCT | TTTTGGTCTCTGCGTCCTCT |

| fmnl3 | CCCCCAAAACTGACCCTAAT | GAATGGACGTCAATGGAAGG |

| EF1α | CTGGTTCAAGGGATGGAAGA | CACACGACCCACAGGTACAG |

PCR products were amplified using an Eppendorf mastercycler epgradient machine, with the following conditions: 2 minutes at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C and 30 seconds at 57°C and 1 minute at 72°C and a final extension of 10 minutes at 72°C. Samples without reverse transcriptase were used as negative controls.

The sequence of the alternative splice variant of fmnl2b: Exon11:GTGGCGTGCATGCAGTTCATCAATATTGTGGTGCA CTCGGTGGAGGACATGAATTTCAGAGTTCACCTTCAGTATGACTTCACCAAAC TCTCTCTGGACGACTATTTGGAG-Exon11a:GTATTAACTTTTTCAAAGTATCTT GCATTCACGCTCCCTCAGAAACTCACTTCCCTGGGGTTTGTGTTTTGTCCGCA G)-Exon12:AGGCTGAAGCATACGGAGAGCGATAAACTCAAAGTGCAGATCC…

2.4-In situ hybridization and histology

In situ hybridization was performed according to established protocols (29). Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were synthesized using a DIG labeling kit (Roche) using the PCR fragments after subcloning into pSCA (Agilent). For Anti-sense probes, plasmid cDNA were linearized using XhoI for fmnl1b, 2a, 2b and 3 and with NotI for fmnl1a and the ribo-probe was synthesized using T7 polymerase. For sense (control) probes, plasmid cDNA were linearized using AscI for fmnl1a, 2a and 3, with HindIII for fmnl2b and with KpnI for fmnl1b and the ribo-probe was synthesized using Sp6 polymerase for fmnl1a, 2a and 3, T7 polymerase for fmnl2b and T3 polymerase for fmnl1b. Probes were detected with anti-DIG-AP antibody (1:5000, Roche) and BM purple substrate (Roche). For all the stages whole-mount ISH was carried out. Histological sections were obtained for a subset of the 24 and 48 hpf embryos.

Sense probes were used as negative controls and no staining were observed (data not shown).

Coronal cryosections were obtained as previously described (30). Briefly: 24 hpf and 48 hpf old embryos were cryoprotected in 15% sucrose in PBS for 12 hours at 4°C and then in 30% sucrose at room temperature during 2 hours. Embryos were embedded in OCT and 18μm sections were obtained using a Leica cryostat.

2.4-Immunohistochemistry

α-acetylated Tubulin (Sigma T6793) staining was performed on sections after the in situ hybridization as previously described (31) and using an Alexa-488 secondary antibody.

2.4-Image analysis

Whole-mount embryos were examined under a Olympus SZ61 microscope with an Olympus America camera. Digital images were taken using Picture Frame software. Cryosections were analyzed on a Axioskop2 plus (Zeiss) with a AxioCam MRc camera (Zeiss) and images were acquired using the Carl Zeiss AxioVision Rel. 4.6 software. Sharpness, contrast, and brightness were adjusted to reflect the appearance seen through the microscope. For final adjustments Adobe® Photoshop® CS3 extended Adobe® Illustrator® CS3 were used.

Highlights.

Phylogenetic relationships between Fmnl Formins, conserved catalysts of linear actin

Fmnls are maternally provided and widely expressed in early zebrafish embryos

Histological analysis of zebrafish fmnls shows distinct and common expression domains

Fmnls show tissue specific expression in the vascular, visual and otic systems

Acknowledgments

Research of the Marlow and Jenny labs is funded by grants NIH RO1 GM1089979 (F.L.M.) and RO1 GM088202 (A.J.) and start up funds to FLM and AJ, respectively. We thank the Einstein Cancer Center supported Histopathology resource for use of the cryotome. We thank P. Campbell and Dr. L. Feng for their valuable comments on the manuscript and Marlow and Jenny lab members for discussion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Solnica-Krezel L. Conserved patterns of cell movements during vertebrate gastrulation. Curr Biol. 2005;15(6):R213–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.016. Epub 2005/03/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. Epub 2007/03/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campellone KG, Welch MD. A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(4):237–51. doi: 10.1038/nrm2867. Epub 2010/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manseau LJ, Schupbach T. cappuccino and spire: two unique maternal-effect loci required for both the anteroposterior and dorsoventral patterns of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1989;3(9):1437–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1437. Epub 1989/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirone P, Lin S, Griesbach HL, Zhang Y, Slusarski DC, Crews CM. A role for planar cell polarity signaling in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11(4):347–60. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9116-2. Epub 2008/09/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schonichen A, Geyer M. Fifteen formins for an actin filament: a molecular view on the regulation of human formins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(2):152–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.014. Epub 2010/01/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schonichen A, Alexander M, Gasteier JE, Cuesta FE, Fackler OT, Geyer M. Biochemical characterization of the diaphanous autoregulatory interaction in the formin homology protein FHOD1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):5084–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509226200. Epub 2005/12/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y, Moseley JB, Sagot I, Poy F, Pellman D, Goode BL, et al. Crystal structures of a Formin Homology-2 domain reveal a tethered dimer architecture. Cell. 2004;116(5):711–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00210-7. Epub 2004/03/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yayoshi-Yamamoto S, Taniuchi I, Watanabe T. FRL, a novel formin-related protein, binds to Rac and regulates cell motility and survival of macrophages. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(18):6872–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6872-6881.2000. Epub 2000/08/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Block J, Breitsprecher D, Kuhn S, Winterhoff M, Kage F, Geffers R, et al. FMNL2 Drives Actin-Based Protrusion and Migration Downstream of Cdc42. Curr Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.064. Epub 2012/05/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heimsath EG, Jr, Higgs HN. The C terminus of formin FMNL3 accelerates actin polymerization and contains a WH2 domain-like sequence that binds both monomers and filament barbed ends. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(5):3087–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312207. Epub 2011/11/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hetheridge C, Scott AN, Swain RK, Copeland JW, Higgs HN, Bicknell R, et al. The formin FMNL3 is a cytoskeletal regulator of angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 6):1420–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091066. Epub 2012/01/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgs HN, Peterson KJ. Phylogenetic analysis of the formin homology 2 domain. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0565. Epub 2004/10/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoh M. Identification and characterization of human FMNL1, FMNL2 and FMNL3 genes in silico. Int J Oncol. 2003;22(5):1161–8. Epub 2003/04/10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesarone MA, DuPage AG, Goode BL. Unleashing formins to remodel the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):62–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm2816. Epub 2009/12/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F, Leder P, Martin SS. Formin-1 protein associates with microtubules through a peptide domain encoded by exon-2. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(7):1119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.12.035. Epub 2006/02/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuh M, Ellenberg J. A new model for asymmetric spindle positioning in mouse oocytes. Curr Biol. 2008;18(24):1986–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.022. Epub 2008/12/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Zhang J, Ahmad S, Rozier L, Yu H, Deng H, et al. Aurora B regulates formin mDia3 in achieving metaphase chromosome alignment. Dev Cell. 2011;20(3):342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.008. Epub 2011/03/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe S, Okawa K, Miki T, Sakamoto S, Morinaga T, Segawa K, et al. Rho and anillin-dependent control of mDia2 localization and function in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(18):3193–204. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0324. Epub 2010/07/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roszko I, Sawada A, Solnica-Krezel L. Regulation of convergence and extension movements during vertebrate gastrulation by the Wnt/PCP pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(8):986–97. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.004. Epub 2009/09/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tada M, Kai M. Noncanonical Wnt/PCP signaling during vertebrate gastrulation. Zebrafish. 2009;6(1):29–40. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0566. Epub 2009/03/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diz-Munoz A, Krieg M, Bergert M, Ibarlucea-Benitez I, Muller DJ, Paluch E, et al. Control of directed cell migration in vivo by membrane-to-cortex attachment. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(11):e1000544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000544. Epub 2010/12/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris ES, Gauvin TJ, Heimsath EG, Higgs HN. Assembly of filopodia by the formin FRL2 (FMNL3) Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67(12):755–72. doi: 10.1002/cm.20485. Epub 2010/09/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y, Eppinger E, Schuster IG, Weigand LU, Liang X, Kremmer E, et al. Formin-like 1 (FMNL1) is regulated by N-terminal myristoylation and induces polarized membrane blebbing. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(48):33409–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060699. Epub 2009/10/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de la Pompa JL, James D, Zeller R. Limb deformity proteins during avian neurulation and sense organ development. Dev Dyn. 1995;204(2):156–67. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040206. Epub 1995/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D, Hallett MA, Zhu W, Rubart M, Liu Y, Yang Z, et al. Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam1) is required for heart morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138(2):303–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.055566. Epub 2010/12/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bang PI, Sewell WF, Malicki JJ. Morphology and cell type heterogeneities of the inner ear epithelia in adult and juvenile zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Comp Neurol. 2001;438(2):173–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.1308. Epub 2001/09/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westerfield M. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; 1995. The Zebrafish Book. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kai M, Heisenberg CP, Tada M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors regulate individual cell behaviours underlying the directed migration of prechordal plate progenitor cells during zebrafish gastrulation. Development. 2008;135(18):3043–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.020396. Epub 2008/08/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerveny KL, Cavodeassi F, Turner KJ, de Jong-Curtain TA, Heath JK, Wilson SW. The zebrafish flotte lotte mutant reveals that the local retinal environment promotes the differentiation of proliferating precursors emerging from their stem cell niche. Development. 2010;137(13):2107–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.047753. Epub 2010/05/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos-Ledo A, Arenzana FJ, Porteros A, Lara J, Velasco A, Aijon J, et al. Cytoarchitectonic and neurochemical differentiation of the visual system in ethanol-induced cyclopic zebrafish larvae. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2011;33(6):686–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.06.001. Epub 2011/06/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]