Abstract

Quality of life (QOL) is a multidimensional construct that includes physical, psychological, and relationship well-being. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies published between 1980 and 2012 of interventions conducted with both cancer patients and their partners that were aimed at improving QOL. Using bibliographic software and manual review, two independent raters reviewed 752 articles with a systematic process for reconciling disagreement, yielding 23 articles for systematic review and 20 for meta-analysis. Most studies were conducted in breast and prostate cancer populations. Study participants (N=2645) were primarily middle-aged (Mean = 55 years old) and white (84%). For patients, the weighted average effect size (g) across studies was 0.25 (95% CI = 0.12-0.32) for psychological outcomes (17 studies), 0.31 (95% CI = 0.11-0.50) for physical outcomes (12 studies), and 0.28 (95% CI = 0.14-0.43) for relationship outcomes (10 studies). For partners, the weighted average effect size was 0.21 (95% CI = 0.08-0.34) for psychological outcomes (12 studies), and 0.24 (95% CI = 0.6 - 0.43) for relationship outcomes (7 studies). Therefore, couple-based interventions had small but beneficial effects in terms of improving multiple aspects of QOL for both patients and their partners. Questions remain regarding when such interventions should be delivered and for how long. Identifying theoretically based mediators and key features that distinguish couple-based from patient-only interventions may help to strengthen their effects on patient and partner QOL.

Keywords: couples, interventions, meta-analysis, cancer, quality of life, randomized-control trial, systematic review, distress, relationship satisfaction, behavior

Introduction

In the cancer literature, social relationships are among the most-studied contributing factor to QOL [1]. Among these relationships, the patient's relationship with his/her spouse or significant other (hereafter referred to as “partner”) is considered paramount as cancer patients identify their partners as their most important sources of support [2]. The diagnosis and treatment of cancer, however, can affect every aspect of both the patients' and their partners' QOL. Patients must cope with the role changes and distress brought about by the physical side effects and increased functional disability associated with their disease and treatment. Their partners must not only confront the potential loss of a life partner (the patient), but also become adept at providing instrumental and emotional support during a time when they themselves are under extreme stress. Coping with cancer treatment can also challenge a couple's established communication patterns, roles, and responsibilities [3; 4]. Thus, it is not surprising that some couples report that the cancer experience brought them closer together, whereas others report experiencing significant adjustment and communication difficulties that may result in feelings of decreased intimacy and greater interpersonal conflict [5; 6].

Traditional approaches for addressing QOL after a cancer diagnosis have focused on either the patient or the patient's partner. However, both members of the couple and their relationship are profoundly affected by the cancer experience. Thus, coping with cancer has been characterized as a dyadic affair [7-9], and a burgeoning literature involving couple-based interventions has emerged over the past 2 decades. Little is currently known regarding the efficacy of couple-based interventions and there is a need for a critical analysis of these interventions to determine whether they can improve both patient and partner QOL. Although there have been several notable reviews in this area [1; 9-14], none have evaluated the efficacy of couple-based interventions on multiple aspects of QOL for both patients and their partners. Thus, the conclusions that can be drawn from existing reviews regarding the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for improving QOL in couples coping with cancer are limited.

To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies that aimed to improve the QOL of cancer patients and their partners. Because QOL is a multidimensional construct that encompasses physical, psychological, and social (interpersonal) well-being [15-18], and because our focus was specifically on couples, studies that examined physical, psychological, or relationship outcomes were included in our review. Our primary aims were to 1) synthesize the findings of existing couple-based interventions aimed at improving the QOL of cancer patients and their partners, 2) estimate the effects of couple-based interventions on the QOL of patients and their partners, and 3) explore the potential moderating effects of intervention characteristics (i.e., design and quality) on the direction and/or strength of the relationship between couple-based interventions and our outcomes of interest.

Methods

Search, Selection, and Review Strategies

Electronic searches were conducted to identify English language journal articles published from January 1980 to July 2012 in the PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, Web of Science, and LISTA (EBSCO) databases. The search terms were “intervention,” “cancer,” “couple,” “dyad,” “spouse,” “symptom management,” “behavioral,” “therapy,” and “psychosocial.” Our strategy was to balance sensitivity (i.e., conducting a broad search that yielded a large number of relevant papers but also many irrelevant ones) with specificity (i.e., weeding out many irrelevant papers but perhaps missing some pertinent ones) [19; 20]. Results were verified by reviewing reference lists from the publications retrieved, including relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

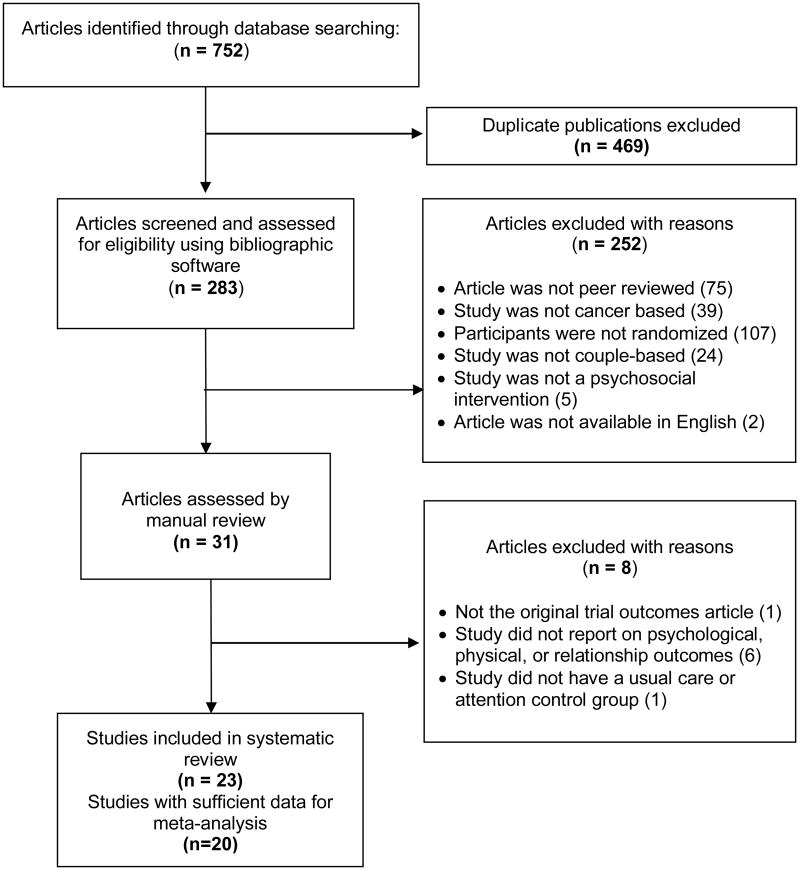

Figure 1 depicts the process used to identify and select relevant journal articles. Two raters abstracted data on intervention design, participant characteristics, theoretical basis, and key findings. Discrepancies were systematically resolved by consensus. Studies were assessed for quality using a modified 11-item version of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) coding scheme which was developed using a Delphi expert consensus technique and designed to identify studies that are generalizable, internally valid, and contain interpretable data [21]. When full text could not be located or when published articles did not present sufficient data, we contacted authors up to three times to request the required information.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Depicting the Systematic Review Process.

Meta-analysis Strategy

We employed Hedges g as the effect size (ES) statistic. Hedges g represents the difference between intervention and control group means (d) divided by their pooled standard deviation multiplied by a factor (J) that corrects for underestimation of the population standard deviation such that g = J × d [22]. By pooling variances, the effect size statistic standardizes outcomes across studies and facilitates comparison among disparate outcome measures. Each study effect size was weighted by its inverse variance weight in calculating mean effect sizes. All effect size calculations employed a random effects estimation model. By incorporating between-study variance, this facilitates generalizability of effect size estimates beyond a given set of studies. In meta-analysis the sample size consists of the number of studies, represented by k, in contrast to N, the number of participants in each study.

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed following suggestions by Hagedoorn and colleagues [9], who recommend evaluating the degree of heterogeneity, identifying studies that contribute to statistical heterogeneity, and conducting a sensitivity analyses with and without these studies being included. Following this advice, we calculated the heterogeneity I2 statistic, which represents the approximate proportion of total variability (0-100%) in point estimates that can be attributed to systematic differences across studies (larger percentages reflect greater heterogeneity). An I2 value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity; values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond with “low”, “moderate,” and “high” levels of heterogeneity, respectively [23].

Outliers within each outcome category were examined for possible correction using methods suggested by Viechtbauer and Cheung [24]. In cases where outliers were identified, we re-ran the analyses – first, with the outlying studies excluded, and again by retaining the outlying studies and Winsorizing their results. Winsorizing is a method that has been advocated for use in meta-analysis [25] and involves coding extreme values back to the next highest value in their respective categories in order to reduce the effect of possibly spurious outliers. Results obtained using both methods for handling outliers were compared and the implications of dropping the outliers versus retaining them with Winsorized results were carefully evaluated.

Our focus on psychological, physical, and relationship outcomes was necessarily broad given the state of the couples' literature in cancer and our interest in examining the effects of couple-based interventions on multiple aspects of patient and partner QOL. Even though most studies articulated whether psychological, relationship, or physical outcomes were the primary target of the intervention, they often assessed these outcomes with multiple measures. Given this and the desire to minimize heterogeneity wherever possible, we prioritized outcomes and measures that were the most frequently reported across studies in each category followed by those that were reported less frequently. For example, for psychological outcomes, general psychological distress (e.g., depression and anxiety symptoms) was the most frequently reported outcome so we prioritized it over assessments of depression alone, cancer-specific distress, and mental well-being. Psychological, physical, and relationship outcomes for patients and partners were examined separately. When studies reported outcomes at more than one follow-up time point, the assessment closest in time to completion of the intervention was used to calculate the ES.

Moderator analysis

Because moderators are often not randomized in the studies being analyzed, moderator analyses conducted in meta-analyses can best be used to shed light on possible trends and directions for future randomized studies. Here, moderator analyses were limited to instances in which groups were represented by at least three studies and were chosen based on factors that have been highlighted in the cancer literature as having the potential to influence how interventions impact patient and/or partner outcomes [1; 26-29]. Moderators related to study design included 1) whether the partner played a supportive role (i.e., the intervention focused primarily on the patient and what that the partner could do to help and support the patient) or the study actively involved the partner (i.e., the intervention addressed both partners' concerns and taught relationship skills to facilitate adaptive coping in both partners), 2) whether the intervention taught spousal communication skills, 3) whether the interventionist was a nurse or person with a mental health background, 4) whether the outcome category being examined was a primary or secondary target of the intervention, and 5) intervention dose (defined as the cumulative number of intervention sessions). Moderators related to study quality were assessed with the modified PEDro scale [21]. All moderators were categorical and examined using a mixed effects approach in which within-group effects were estimated using random effects and between-group differences were estimated with a fixed effects model. Within and between groups heterogeneity were examined using the Q statistic, which is distributed as a chi-square and compares between and within-study variability [30].

Sources of bias

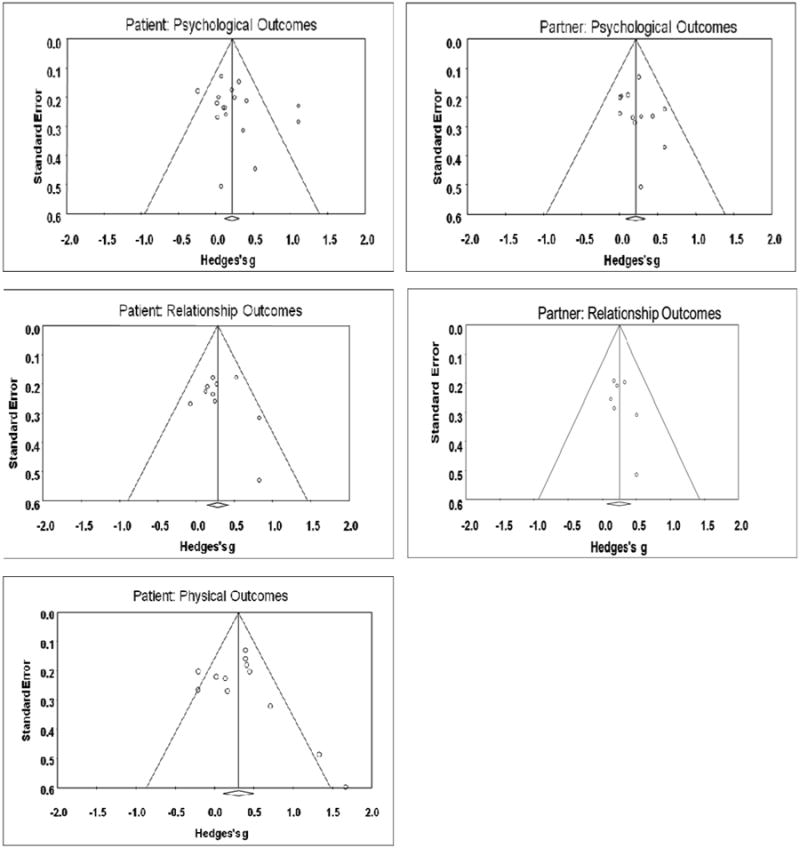

Mean effects for each category were assessed for degree of publication bias (i.e., the over-representation of small studies with positive effects) using two techniques: examination of the funnel plot and trim and fill. The funnel plot graphs the effect size of each study by its respective standard error. If points are distributed equally between positive and negative effects, bias is lacking; variability is expected to be greater near the bottom of the chart among smaller studies. Trim and fill assesses the symmetry of the funnel plot under the assumption that when publication bias exists, a disproportionate number of studies will fall to the bottom right of the plot [31]. To examine stability of the overall effect, we calculated the fail-safe N which determines the number of studies with a null effect size needed to reduce the overall effect to non-significance. We used the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package to conduct all statistical analyses [30].

Systematic Review Results

Participant and design characteristics of the 23 studies included in the systematic review are summarized in Table 1 and are described in detail in Table 2. Overall, most studies focused on breast or prostate cancer in couples coping with early stage disease and varied in terms of number of sessions, session length, number and length of follow-ups, and mode of delivery. In addition, most studies did not specify how theory was used in the development of intervention materials or examine mediators of intervention effects.

Table 1. Participant and Design Characteristics of Studies in the Systematic Review (k = 23).

| Mean±SD | Number (%) of Studies | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Cancer Type | ||

| Breast | 7(30) | |

| Prostate | 7(30) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 1(5) | |

| Lung | 1(5) | |

| Mixed | 7(30) | |

| Sample Size | 115.00±77.28 | |

| Participant Age | 54.91±6.48 | |

| Percent Non-white* | 16.03%±9.32% | |

| Refusal Rate | 46.76%±26.46% | |

| Attrition Rate | 23.55%±11.73% | |

| Type of Control Group | ||

| Usual Care | 12(52) | |

| Attention Control | 6(26) | |

| Wait-list Control | 2(9) | |

| Psychosocial Services | 3(13) | |

| Interventionist | ||

| Mental Health Background | 14(61) | |

| Nurse | 9(39) | |

| Role of Partner | ||

| Supportive | 12(52) | |

| Active | 11(48) | |

| Communication Addressed | ||

| Yes | 16(70) | |

| No | 7(30) | |

Table 2. Systematic Review of Randomized Psychosocial Interventions Involving Couples Coping with Cancer (k = 23).

| Sample Demographics | Refusal rate, Follow-up, and Attrition | Theoretical Model, Therapy Type, and Intervention Delivery/dosage | Intervention and Control Group Content | Main Findings for Patients and Partners | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Badger, 2007[36] |

N: 96 breast cancer patients and partners (63% spouses; 14% significant others) Mean age: 53 |

Refusal rate: 17% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 1 month Attrition: 5% of patients; 11% of partners |

Theory: No explicit theory; elements of SCPM Therapy: Interpersonal counseling, education Delivery/dosage: 6 weekly calls for patients; 3 separate calls for partners delivered by nurses. |

CI: Cancer education and communication skills training SI: Couples' exercise protocol Attention control: patients and partners received pamphlets about breast cancer and separate telephone calls |

Patients and partners in the CI and second intervention arm experienced decreased anxiety relative to controls. |

| Baucom, 2009[46] |

N: 14 breast cancer patients and spouses Mean age: Not specified |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: Post-intervention, 12 months Attrition: NS |

Theory: No explicit theory; elements of dyadic coping Therapy: CBT, BMT Delivery/dosage: 6 75-minute biweekly in-person sessions delivered by psychology doctoral students |

CI: Communication training, problem-solving, sexual counseling Control: UMC |

Patients and partners in the CI arm experienced improved psychological and relationship functioning compared to controls. Patients in the CI arm also reported fewer medical symptoms at follow-up. |

| Budin, 2008[37] |

N: 249 breast cancer patients and partners (60% spouses/significant others) Mean age: 52 |

Refusal rate: 51% Follow-up: Post-surgery, adjuvant therapy, and ongoing recovery Attrition: 29% |

Theory: Stress and coping theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: Combination of 4 in-person and telephone sessions delivered to patients and partners separately by nurses |

CI: Counseling to facilitate coping, behavior change, and communication SI: Disease-management education and telephone counseling for patients and partners separately TI: Disease-management education for patients and partners separately Attention control: Disease- management education |

Patients in the CI arm experienced improvements in psychological well-being from post-surgery to the adjuvant therapy phase; however, this was followed by a decrease in well-being. For partners, no significant differences were found. |

| Campbell, 2004[42] |

N: 40 African-American prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 60 |

Refusal rate: 71% Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: 25% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: Education, CBT Delivery/dosage: 6 1-hour weekly calls with a trained, African-American doctoral-level psychologist via speakerphone |

CI: Patients and partners were provided information about prostate cancer and possible long-term side effects, problem solving skills, cognitive and behavioral coping skills training Control: UMC |

Patients in the CI arm reported improved disease-specific QOL. Partners in the CI arm reported modest improvements in depressive symptoms and fatigue. |

| Canada, 2005[41]* |

N: 84 prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 61 |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: 3 and 6 months Attrition: 39% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: Education, skills-training, and CBT Delivery/dosage: 4 in-person weekly sessions delivered by psychologists or counselors |

CI: Education, training to improve sexual communication and expression of feelings, cognitive-behavioral techniques to address negative beliefs about cancer and sexuality Control: Same as above but for patients only |

Patients in the CI arm demonstrated improvement in distress and patients and partners demonstrated improvement in sexual function at the 3 month follow-up. |

| Christensen, 1983[32]* |

N: 20 breast cancer patients and spouses Mean age: 40 |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: NS |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: Education, BMT Delivery/dosage: 4 in-person weekly sessions delivered by psychologists |

CI: Counseling focused on communication and problem-solving skills, and body image/sexuality Control: UMC |

The CI arm resulted in modest decreases in emotional discomfort for both partners and patients, reduced depression in patients, and increased sexual satisfaction for both partners and patients. |

| Giesler, 2005[33] |

N: 99 prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 64 |

Refusal rate: 68% Follow-up: 4, 7, and 12 months Attrition: 14% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: Education and skills training Delivery/dosage: 6 monthly sessions (2 in person, 4 telephone) delivered by nurses |

CI: Tailored couples education, support, and problem-solving Control: UMC |

Patients in the CI arm reported better sexual function, fewer sexual limitations, and less cancer worry. No outcomes were reported for partners. |

| Heinrichs, 2011[38] |

N: 72 breast or gynecological cancer patients and partners Mean age: 52 |

Refusal rate: 58% Follow-up: Post-intervention, and 6 and 12 months later Attrition: 31% (45% in control group and 17% in CI group) |

Framework: Dyadic coping Therapy: Cognitive behavior couples therapy Delivery/dosage: 4 biweekly 2-hour in-person sessions delivered by therapists in the patient's home |

CI: Communication skills and dyadic coping training Attention Control: One 2-hour cancer education session for couples |

Patients in the CI arm experienced larger reductions in fear of progression, and both patients and partners in the CI arm reported less avoidance in dealing with the cancer, more posttraumatic growth, and better relationship skills relative to those in the attention control arm. |

| Kalaitzi, 2007[35] |

N: 40 breast cancer patients and partners Mean age: 52 |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: NS |

Framework: No explicit theory Therapy: Education, cognitive behavior couples therapy, sexual therapy Delivery/dosage: 6 biweekly in-person sessions delivered by therapists |

CI: Education, communication training, and sexual counseling Control: UMC |

Patients in the CI arm experienced less depression and anxiety, greater satisfaction with their relationship, and greater orgasm frequency. No outcomes were reported for partners. |

| Kayser, 2010[39] |

N: 63 breast cancer patients and partners Mean age: 46 |

Refusal rate: 82% Follow-up: 6 and 12 months Attrition: 25% |

Theory: No explicit theory, Elements of dyadic coping Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 9 biweekly 1-hour in-person sessions over 5 months delivered by social workers |

CI: Couples coping and communication skills training, addressing impact of cancer on daily life, enhancing intimacy and sexual functioning Control: Standard social work services |

Patients and partners in the CI arm reported improvements in psychosocial adjustment over time relative to controls. |

| Keefe, 2005[52] |

N: 78 mixed cancer patients with advanced disease and partners (76% spouses) Mean age: 59 |

Refusal rate: 53% Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: 28% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 3 in-person sessions in patient's home delivered over 1-2 weeks by nurses |

CI: Education about cancer pain and management, pain coping strategies training, and how to help the patient acquire and maintain coping skills Control: UMC |

The CI arm did not have a significant impact on patients' QOL. Partners enrolled in the intervention reported modest improvements in their levels of caregiver strain compared with partners in the control arm. |

| Kuijer, 2004[51] |

N: 59 mixed cancer patients and partners Mean age: 50 |

Refusal rate: 3% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 3 months Attrition: 34% |

Theory: Equity theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 5 90-minute biweekly in-person sessions delivered by psychologists |

CI: Improving the exchange of social support and restoring equity Wait-list control: UMC |

Patients in the CI arm reported lower levels of psychological distress relative to controls. Patients and partners in the CI arm also reported better relationship quality post-intervention relative to controls. |

| Manne, 2005[47] |

N: 238 breast cancer patients and spouses Mean age: 49 |

Refusal rate: 67% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 months Attrition: 32% |

Theory: No explicit theory; Elements of the SCPM Therapy: CBT and BMT Delivery/dosage: 6 90-minute sessions delivered weekly in a group by therapists |

CI: Stress management, problem solving as a team, respecting coping differences, enhancing support exchanges and communication skills, anticipating changes in the couple's relationship after cancer Control: UMC |

Compared to controls, patients in the CI arm reported greater reductions in symptoms of depression post-intervention and at the 6-month follow-up. Patients who had higher levels of physical impairment before the intervention benefited more from the intervention than those with lower levels of physical impairment. No outcomes were reported for partners. |

| Manne, 2011[44] |

N: 71 prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 58 |

Refusal rate: 79% Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: 8% patients; 15% partners |

Theory: Intimacy theory Therapy: CBT and BMT Delivery/dosage: 6 90-minute in-person sessions delivered weekly by therapists |

CI: Communication skills training to improve support exchanges and enhance emotional intimacy Control: Standard psychosocial care (patient consultation with a social worker) |

Patients with higher levels of pretreatment cancer concerns reported significant reductions in concerns post-treatment. Partners who had higher cancer-specific distress, lower marital satisfaction, less marital intimacy, and poorer communication at baseline, reported significant improvements in these outcomes post-treatment. |

| McCorkle, 2007[43] |

N: 107 prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 58 |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: 1,3, and 6 months Attrition: 15% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 16 in-person and telephone sessions delivered by nurses over 8 weeks |

CI: Symptom-management education, communication training, and sexual counseling Control: UMC |

The CI arm had a modest positive effect on patients' sexual function and marital interaction over time; however, patients in the CI arm reported greater distress over time. Similar findings were reported for partners. |

| McLean, 2011[53] |

N: 42 mixed cancer patients and spouses where the patient had metastatic disease and at least one partner reported marital distress Mean age: 50 |

Refusal rate: 7% Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: 10% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: EFT Delivery/dosage: 8 one hour in-person weekly sessions delivered by a psychologist |

CI: Communication training, controlling physical symptoms, dealing with physical changes and functional decline, end-of-life decision making, spending time in a meaningful way and life review, dealing with role changes and existential issues Control: Standard psychosocial care provided by the Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care Program delivered by either a social worker, psychologist, or psychiatrist |

Patients and partners in the CI arm experienced significant improvements in marital functioning and patients reported significant improvements in caregiver empathic care compared to those in the control arm. |

| Mishel, 2002[34] |

N: 252 prostate cancer patients and partners Mean age: 64 |

Refusal rate: 33% Follow-up: 4 and 7 months Attrition: 5% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 8 weekly calls delivered by nurses to patients and partners separately |

CI: Tailored couples education, cognitive reframing, problem solving, and patient-provider communication training SI: Education, cognitive reframing, problem solving, and patient-provider communication training for the patient Control: UMC |

Both the CI and second intervention arms were effective in reducing patient uncertainty and incontinence relative to the control arm. No outcomes were reported for partners. |

| Nezu, 2003[49] |

N: 150 mixed cancer patients and family members (95% spouses) Mean age: 47 |

Refusal rate: NS Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 and 12 months Attrition: 12% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: CBT Delivery/dosage: 10 90-minute weekly in-person sessions delivered by psychology graduate students and social workers |

CI: Couples problem-solving training SI: Problem-solving therapy for patients Wait-list control: UMC |

Patients in both the CI and second intervention arms reported less negative mood, depression, cancer-related problems, psychiatric symptoms, and distress than patients in the control arm. No outcomes were reported for partners. |

| Northouse, 2007[45] |

N: 235 prostate cancer patients and spouses Mean age: 61 |

Refusal rate: 33% Follow-up: 4, 8, and 12 months Attrition: 17% |

Theory: Individual Stress and Coping Theory Therapy: CBT, BMT Delivery/dosage: 5 biweekly sessions (3 90-minute home visits and 2 30-minute calls) delivered by trained masters-level nurses over four months |

CI: Tailored education, enhancement of couples communication and support, coping effectiveness, uncertainty reduction, symptom management, family involvement, and optimism Control: UMC |

No significant differences between the CI and control arms were noted for patients. Spouses in the CI arm reported better QOL, less distress, and better communication with the patient. |

| Porter, 2009[50] |

N: 130 gastrointestinal cancer patients and partners Mean age: 59 |

Refusal rate: 75% Follow-up: Post-intervention Attrition: 21% |

Theory: No explicit theory; elements of the SCPM Therapy: CBT, BMT Delivery/dosage: 4 in-person sessions ranging from 45-75 minutes delivered by trained social workers and psychologists |

CI: Strategies to facilitate patient disclosures about their cancer-related concerns Attention control: Education, suggestions for communicating with providers, resources for health information, and suggestions for maintaining QOL |

Patients who had higher pre-treatment levels of holding back cancer-related concerns and who were in the CI arm evidenced post-treatment improvements in relationship quality and intimacy relative to those in the control arm. |

| Porter, 2011[59]* |

N: 233 lung cancer patients and caregivers (76% spouses) Mean age: 62 |

Refusal rate: 40% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 4 months Attrition: 40% |

Theory: No explicit theory; elements of the SCPM Therapy: CBT, BMT Delivery/dosage: 14 45-minute sessions over the telephone with trained nurses via speakerphone |

CI: Individual coping skills training, communication skills training, smoking cessation counseling, caregiver concerns, maintenance strategies Attention control: Medical information |

Patients in the CI and attention control arms showed improvements in pain, depression, QOL, and self-efficacy. Caregivers in both arms showed improvements in anxiety and self-efficacy. |

| Scott, 2004[40] |

N: 94 breast or gynecological cancer patients and spouses Mean age: 52 |

Refusal rate: 6% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 6 and 12 months Attrition: 21% patients; 30% partners |

Theory: No explicit theory; elements of the SCPM Therapy: CBT, BMT Delivery/dosage: 4 120-minute sessions in patients' homes and 2 30-minute calls delivered by psychologists |

CI: Medical information, communication skills training, social-support training, sexual counseling, discussion of existential concerns, individual coping skills training SI: Medical Information, coping skills training, and supportive counseling for patients Attention control: Medical information |

Compared with the second intervention and control arms, the CI arm increased patients' and partners' perceptions of the couples' supportive communication, decreased patients' distress, and improved patients' intimacy with their partners. |

| Ward, 2009[48] |

N: 161 mixed cancer patients and partners Mean age: 57 |

Refusal rate: 52% Follow-up: Post-intervention, 5 and 9 weeks Attrition: 32% |

Theory: No explicit theory Therapy: Education Delivery/dosage: One in-person session lasting 20- 80 minutes and follow-up calls delivered by nurses |

CI: Beliefs about cancer pain, barriers, pain medication, attitudes, coping and pain management plan SI: Same as couples' intervention arm except only patient received the intervention Control: UMC |

Patients in both intervention arms reported significant decreases in attitudinal barriers relative to controls. No significant differences were found for partners. |

Note: NS=Not specified; SCPM=Social Cognitive Processing Model; CBT=Cognitive-behavioral therapy; BMT=Behavioral Marital Therapy; UMC – patient received usual medical care; CI =Couples Intervention Arm; SI = Second Intervention Arm; TI = Third Intervention Arm; Studies marked with an * were included in the systematic review but not in the meta-analysis.

Participant Characteristics

Participants' (both patients and partners) were predominately white (83.97%). Their mean age was 55 years (range of mean age=40 [32] to 64 years [33; 34]). For those studies that focused exclusively on female [32; 35-40] or male cancers [33; 34; 41-45], the mean age for female patients was 49.84 (SD=9.66) and the mean age for male patients was 62.09 (SD=8.18). The total number of couples enrolled was 2645 but varied considerably by study, from 14 [46] to 252 [34]. Nine studies had sample sizes ≥ 100 [34; 37; 43; 45; 47-50]. Of the 17 studies that provided information on recruitment, the mean refusal rate was 47% (range=3%[51] to 82%[39]). At final follow-up, the mean attrition rate was 24% (range=5%[34] to 39%[41]). With the exception of two studies [52; 53], the target of most interventions was couples coping with non-metastatic disease.

Design Characteristics

Eleven studies [32-35; 41-43; 48; 49; 52; 53] had no explicit or implied theoretical framework. Individual stress and coping models, which grounded two studies [45; 54], view social support as a form of coping assistance [55] and posit that person-, social-, and illness-related factors influence how people appraise and cope with an illness. Resource theories (e.g., social cognitive processing model [56], equity theory[57]), which grounded or had elements present in six studies [40; 47; 50; 51; 58; 59], view the partner and relationship as resources patients can draw upon for assistance during difficult life events. Finally, dyadic models (e.g., communal [7] or dyadic coping[38; 60], intimacy theory[1]) which grounded four studies [38; 44; 46; 61], focus on joint problem-solving, coordinating everyday demands, and approaching cancer together as a team.

Most interventions involved six sessions; however the number of sessions ranged from 1[48] to 16 [43], and session-length varied from 20 to 120 minutes. Seven studies had only one follow-up [32; 35; 36; 42; 44; 50; 52], eight studies [34; 39; 41; 46; 47; 51; 53; 59] had two follow-ups, and eight studies [33; 37; 38; 40; 43; 45; 48; 49] had three follow-ups. Follow-up timing ranged from post-intervention to up to 12 months later. Thirteen interventions involved in-person sessions [32; 35; 38; 39; 41; 44; 46; 47; 49-53], four were by telephone [34; 42; 58; 59], and six involved both [33; 37; 40; 43; 48; 62]. Although most in-person interventions were conducted at the care center, two were conducted in couples' homes [40; 52]. Therapeutic techniques that were employed included cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), education, interpersonal counseling, behavioral marital therapy, and emotion-focused therapy.

Partners were involved in the intervention in one of two ways. The first method, used in 12 studies [33-37; 40; 42; 48-50; 52; 59], treated the partner as an assistant or “coach” to facilitate learning and coping skills in the patient. This approach, sometimes described as “partner-assisted” [50; 63], conceptualizes the role of the partner in the intervention as being supportive of the patient [29]. Most studies that used this method required that the partner be present with the patient during all sessions, although the patient and partner received separate instruction in three studies [34; 36; 37]. The second method, used by the eleven remaining studies, sought to actively involve the partner (e.g., by focusing on how the couple functions together as a unit and addressing both partners' needs and concerns). In these studies, both patient and partner were present in the room and treated together. Even though both patients and partners participated in all the interventions, five studies reported no outcomes for partners [33-35; 49; 64].

Meta-Analysis Results

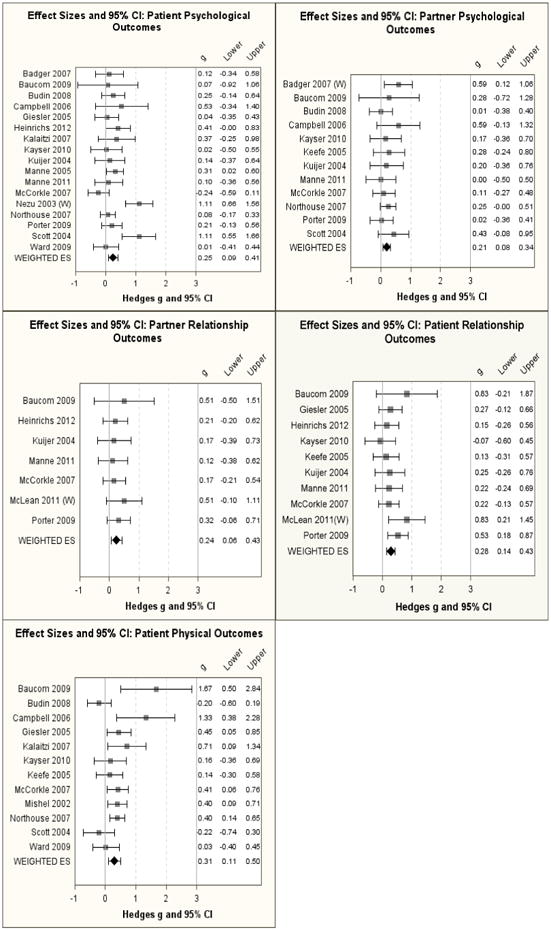

There was insufficient data reported to compute an effect size in three [32; 41; 59] of the 23 studies in our systematic review, leaving 20 studies for meta-analysis. Three studies were identified as containing results that qualified as outliers, with one [49] reporting patient psychological outcomes, one reporting [36] partner psychological outcomes, and one reporting both patient and partner relationship outcomes [53]. Table 3 details the weighted average effect size across studies as well as heterogeneity statistics for patients and partners for each of the outcomes of interest. Both the results for the analyses conducted with the outliers removed and using the Winsorized results are presented. As Table 3 shows, there was very little difference in the heterogeneity I2 statistic or effect sizes across outcomes using the two methods. Given this and the fact that two of the outlying studies had relatively large sample sizes [36; 49] and that the third focused specifically on couples where the patient was at the end-of-life [53], we opted to retain them and use Winsorized results for the outliers in subsequent analyses. Forest plots and confidence intervals for each patient and partner outcome category using the Winsorized results are shown in Figure 2. Results of analyses to detect publication bias are detailed in Table 3 and funnel plots are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3. Mean Effect Sizes for Patient and Partner QOL Outcomes for Studies with Sufficient Data for Meta-Analysis (k=20).

| Patients | Partners | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| k | Effect Size (g) | 95% CI | p-value | Heterogeneity | Fail Safe N | k | Effect Size (g) | 95% CI | p-value | Heterogeneity | Fail Safe N | |

| Outliers Were Deleted | ||||||||||||

| Psychological | 16a | .18 | .05 - .31 | .01 | Q=21.81, p=.11 I2=31.2 | 35 | 11b | .18 | .05 - .31 | .01 | Q=4.67, p=.91 I2=0.00 | 10 |

| Physical | 12 | .31 | .11 - .50 | .001 | Q=25.7, p=.01 I2=57.2 | 68 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Relationship | 9c | .25 | .11 - .40 | .001 | Q=5.6, p=.69 I2=0.00 | 15 | 6 | .22 | .03 - .41 | .02 | Q=.85, p=.97 I2=0.00 | 3 |

| Outliers Were Winsorized | ||||||||||||

| Psychological | 17d | .25 | .12-.32 | .001 | Q=37.77, p=.002 I2=57.64 | 76 | 12e | .21 | .08-.34 | .001 | Q=7.4, p=.97 I2=0.00 | 22 |

| Relationship | 10f | .28 | .14-.43 | .001 | Q=8.77, p=.46 I2=0.00 | 32 | 7f | .24 | .06-.43 | .01 | Q=1.64, p =.95 I2=0.00 | 7 |

Note: CI=Confidence Interval;

Nezu deleted;

Badger deleted;

McLean deleted;

Nezu was Winsorized;

Badger was Winsorized;

McLean was Winsorized

Figure 2. Forest Plots of Patient and Partner Effect Sizes and 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 3. Funnel Plots of Patient and Partner Outcomes.

Table 4 details moderator analyses. We were unable to conduct analyses for partner relationship outcomes due to an insufficient number of studies for comparison. In addition, no significant moderators were found for partner psychological outcomes or for patient relationship outcomes, so those results were not tabled. For psychological outcomes, interventions delivered by individuals with a mental health background evidenced significantly higher effect sizes (k = 11, g = 0.40) than those delivered by nurses (k = 6, g = 0.04), p = .01. There was also a trend (p=.09) for interventions that conceptualized the role of the partner as supportive to evidence higher effect sizes (k = 12, g = .39) than those where the role of the partner was active (k = 8, g = .12). For physical outcomes, there was a trend (p = 0.08) for interventions that addressed spousal communication to evidence higher effect sizes (k = 8, g = 0.44) than those that did not (k = 4, g = 0.11). Number of sessions was not related to either patient psychological (p=.20) or physical outcomes (p=.09).

Table 4. Moderator Analyses for Patient Psychological and Physical Outcomesa.

| Intervention Characteristics | Patient Psychological Outcomes | Patient Physical Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | p-value | B | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Number of sessions | -.02 | -.05-.01 | .20 | .03 | -.01-.06 | .09 | |||

| Level | k | Effect Size (g) | 95% CI | p-value | k | Effect Size (g) | 95% CI | p-value | |

| The outcome measured was primary/secondary | Primary | 13 | .31 | .09-.52 | .11 | 8 | .28 | .04-.53 | .73 |

| Secondary | 4 | .21 | -.10-.26 | 4 | .36 | -.02-.75 | |||

| Spousal communication was addressed in the intervention | No | 5 | .33 | -.06-.71 | .59 | 4 | .11 | -.16-.38 | .08 |

| Yes | 12 | .21 | .04-.38 | 8 | .44 | .18-.70 | |||

| The role of the partner in the intervention was active/supportive | Active | 8 | .12 | -.03-.27 | .09 | 4 | .43 | .13-.72 | .36 |

| Supportive | 9 | .39 | .12-.67 | 8 | .24 | -.02-.51 | |||

| The intervention was delivered by a mental health professional (MHP) or nurse | MHP | 11 | .40 | .18-.62 | .01 | 5 | .60 | -.01 – 1.21 | .29 |

| Nurse | 6 | .04 | -.11-.18 | 7 | .26 | .08 – .43 | |||

| Select Modified PEDro Criteria | |||||||||

| 3. The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators | No | 5 | .33 | -.06-.72 | .62 | 5 | .30 | -.06-.66 | .93 |

| Yes | 12 | .22 | .04-.40 | 7 | .32 | .06-.58 | |||

| 6. All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated, or data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by “intention to treat” | No | 5 | .02 | -.16-.19 | .02 | 4 | .42 | .17-.68 | .35 |

| Yes | 12 | .34 | .14-.53 | 8 | .24 | -.03-.51 | |||

| 9. The study had an adequate treatment fidelity protocol, including manualized treatment | No | 5 | .07 | -.14-.28 | .10 | 3 | .44 | .22-.66 | .29 |

| Yes | 12 | .32 | .11-.53 | 9 | .25 | -.01-.52 | |||

| 10. The study had an adequate treatment fidelity protocol, including monitoring of treatment implementation | No | 4 | .00 | -.24-.24 | .04 | 4 | .44 | .25-.63 | .24 |

| Yes | 13 | .32 | .13-.50 | 8 | .23 | -.07-.53 | |||

Winsorized means used for all moderator analyses

Quality of Studies

A review of findings using the modified PEDro scale revealed that all 23 studies included in the systematic review specified eligibility criteria, randomly allocated participants to groups, obtained measures of at least one key outcome from more than 85% of the original participants, reported results of between-group comparisons for at least one key outcome, and provided both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome. Four studies (17%) blinded assessors [33; 46; 50; 59]; 14(61%) reported manualized treatment [33; 37-40; 42; 44-49; 52; 59], 15(65%) monitored treatment implementation [36-40; 42; 44-50; 52; 63], and 14(61%) had treatment and control groups that were similar at baseline [35-37; 39; 42-45; 47; 49-52; 63].

As Table 4 shows, PEDro criteria with sufficient variability (20-80% of studies) were examined as potential moderators of intervention effects for patients and partners for each of the study outcomes. Of the 20 studies that were meta-analyzed, those where all subjects received the treatment or control as allocated or data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by “intention to treat” [33-38; 40; 44; 46-50; 52] showed a significantly (p = 0.02) larger effect for patient psychological outcomes (k = 12, g = 0.34) compared to those that did not (k = 5, g = 0.02). Studies that monitored treatment implementation [33; 36-40; 42; 44-48; 50; 52] showed significantly larger effect sizes (p = .04) for patient psychological outcomes (k = 13, g = .32) compared to those that did not (k = 4, g = 0), and there was a trend (p=.10) for studies with manualized treatment to show larger effect sizes (k = 12, g=.32) relative to those that did not (k = 5, g=.07).

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis to systematically evaluate the efficacy of RCTs involving couples to improve patient and partner QOL. Strengths include the examination of multiple QOL outcomes for both patients and partners and the assessment of moderators that have been identified as having potential clinical relevance. Findings suggest that couple-based interventions hold promise for improving multiple aspects of both patient and partner QOL.

While the primary take-away point of this meta-analysis is not the findings of the moderator analyses per se, but rather whether couple-based interventions affect multiple QOL outcomes for patients and their partners, it is interesting that few of the factors that we examined moderated the effects of couple-based interventions on QOL. This may be partially attributed to low power related to within-group heterogeneity. We did, however, find significant differences in psychological outcomes depending on the background of the provider. While these findings suggest that greater integration of mental-health providers as part of the intervention team may be warranted when improvement in psychological outcomes are sought, they should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, the mental health background category was heterogeneous and consisted of social workers, psychology graduate students, clinical psychologists, and masters level counselors and therapists. Thus, without examining factors such as educational preparation or years in practice, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions. We urge investigators to provide more detailed information on the training and background of interventionists so that future meta-analyses can more thoroughly investigate this issue.

Moderator analyses examining the PEDro quality criteria showed that participants who received the treatment or control as allocated and that monitored treatment implementation had better psychological outcomes than those who did not. One reason why no other significant differences among studies were found is that the PEDro coding scheme only accounts for the presence or absence of the quality factors - not the extent to which they were implemented. Study participants were also not originally randomized into any of the moderator categories examined across studies. Thus, our estimates are only suggestions of design factors that may influence treatment effects and need to be tested in future RCTs.

Additional variables may be worthy of future examination as moderators of intervention effects. For example, three interventions [44; 50; 64] only benefited a subset of couples – specifically, those who had poorer functioning relationships, greater cancer-related distress, or poor communication skills at the outset. Research is needed to determine whether there are profiles of at-risk couples who may benefit from such interventions, and whether it is necessary to screen for marital and/or psychological distress in both the patient and partner (or just the patient). On a related note, we did not examine gender as a potential moderator of intervention effects. Although there is evidence to suggest that gender differences in distress exist [9], most of the RCTs that were reviewed focused on single-gender cancers (e.g., prostate), confounding the possible effects of gender and social role. Finally, most studies involved couples where the patient was newly diagnosed and had early-stage disease; the longest follow-up was 12 months. Thus, it is unclear how the length of treatment or timing of intervention may have affected outcomes or whether booster sessions were needed to maintain the impact of intervention.

Overall, this review highlights methodological limitations in the couples' intervention literature. Often, researchers did not articulate a theoretical model. Few examined the mechanisms by which interventions affected outcomes, so there are questions as to whether the theoretical basis of the intervention was as hypothesized. Most studies had small sample sizes and thus were underpowered to examine changes in the multiple outcomes that were measured. Some did not include information on refusal or attrition rates, suggesting reporting standards could improve.

Although high levels of recruitment are important in order to bolster generalizability and to provide services to the widest range of couples possible, refusal rates in the studies we reviewed varied widely from 3-82%. One way to view these refusal rates is to consider them in the larger context of enrollment clinical trials, where only 5-30% of adult cancer patients participate [65; 66]. Documented barriers such as distance from the trial center, fear of randomization, and perceived burden of trial participation are only compounded when recruiting for couple-based studies because both members of the couple need to agree to participate. While detailed descriptions of the barriers to enrolling couples were not routinely provided in the studies we reviewed, those that did provide this information cited intervention timing or scheduling issues (i.e., patients said they were too busy or overwhelmed to participate) and age (i.e., younger couples are more likely to enroll than older couples) as key factors [45; 47]. Additional barriers may include timing and location of recruitment, and limited physician involvement in the recruitment process [67]. Incorporating strategies to reduce burden in couples' protocols such as approaching couples at routine clinic visits instead of at the time of diagnosis, scheduling study-related appointments with medical appointments, decreasing the number of sessions or assessments, and conducting sessions by phone, the internet, or in patients' homes may help to bolster enrollment. Likewise, enlisting physicians or clinic staff to introduce the study and reinforce the perception that it is an important part of the patient's overall medical care may also be helpful [67].

One quarter of the studies that we reviewed did not report outcomes for partners and this is likely because these studies leveraged the partner and/or the couples' relationship primarily to improve the well-being of the patient. At the same time, studies that reported outcomes for patients and partners often demonstrated unequal effectiveness for both. Indeed, a lack of patient improvement could be explained by negative but unexamined effects on the partner or the possibility that patients and partners respond to intervention at different rates. Future studies should include both partners and ensure that the couple is the unit of analysis throughout the research process. This dyadic perspective should be reflected when researchers are conceptualizing their research questions, choosing a study design, selecting measures, and analyzing their data. Indeed, most studies analyzed the data that they obtained from patients and partners separately. This does not clearly indicate whether the relationship between a predictor and outcome differs significantly between patients and partners, and points to the need for the use of more sophisticated dyadic data analytic methods [68].

Most studies included white participants, ignoring the possibility that race and culture may influence the importance of the couple relationship in patient adaptation. Study demographics also likely reflect who has access and ability to attend intervention programs and may have excluded patients who lived far away from their care center, had transportation problems, or had physical limitations that made travel difficult. Creating interventions that can be easily and widely disseminated is critical to advancing this field and providing equal access. Emerging communication technologies (e.g., internet, mobile health technologies, social media) may allow for widespread dissemination. More research is needed to determine couples' intervention preferences, whether factors such as advanced disease status, age, or comfort with technology affect receptivity and uptake, and whether such interventions are feasible and cost-effective.

While our findings support the efficacy of couples-based interventions, effect sizes ranged from 0.21 to 0.31. Put in context, the modal effect size for psychological and behavioral interventions ranges from 0.30-0.50 [25]; thus, the effect sizes reported here fell on the lower end of this continuum. This may be partially attributed to the varied or absent theoretical bases, the varied intervention approaches used, and the diversity in outcomes reported. One of the strengths of meta-analysis is that it provides the ability to combine the results of what are often underpowered studies to arrive at a more reliable estimate of effect size [22]. It is particularly appropriate for examining trends as sample sizes in couple-based intervention studies tend to be small, thus confounding clinical and statistical significance. Indeed, our forest plots showed that few individual studies excluded zero from the confidence intervals, but in aggregate they yielded a significant effect size. This means that a number of studies did not result in statistically significant outcomes but when combined resulted in a significant effect size – a common finding that underscores the rationale for conducting meta-analysis. Lack of significant results in individual studies may be attributed to some participants having very little distress, physical symptoms, or relationship problems to begin with or that some studies did not use stringent screening criteria prior to enrolling participants. More work is also needed to clarify the definition of clinically meaningful changes in the outcomes examined as even small effect sizes can still be clinically significant and important.

Overall, several patterns emerged from this meta-analysis that we hope will guide future research. For example, while some interventions addressed cancer-specific issues, content was modified from marital therapy interventions developed for healthy populations or from existing CBT interventions developed for individuals coping with cancer. The standard dose of CBT is 8-12 sessions; however, most couple-based interventions were comparatively brief, comprising ≤ six sessions. This is likely reflective of the difficulty of recruiting and retaining patients undergoing active treatment. Although intervention dosage (number of sessions) was not found to be a significant moderator of effects, more research is needed to determine if there is an optimum intervention dosage for couple intervention studies and whether this varies based on type of outcome. It also remains unclear whether it is appropriate to modify individual-based interventions for use with couples and whether it is feasible or even necessary to address long-standing issues in the dyad in order to affect change in illness-specific outcomes (e.g., symptom management, caregiving).

Baucom and colleagues have argued that couple-based interventions may be best applied in different ways, depending on the presenting difficulties and issues confronted by the couple [29]. For example, if a couple is dissatisfied, the treatment focus should be to intervene on the relationship, and couple therapy techniques would be indicated. However, in non-distressed couples it may be more appropriate for interventions to prepare cancer patients and their partners for the medical and psychosocial challenges they will face, educate them about things they can do to manage cancer- and treatment-related side effects, and provide skills training to create a supportive context where the couple can discuss and address these challenges together. The best way to involve the partner in such interventions remains an empirical question. Indeed, almost half of the interventions that we reviewed conceptualized the partner's role as supportive and half sought to actively involve the partner. Although there was a trend (p=.10) for interventions that conceptualized the role of the partner as supportive to evidence greater effect sizes for patient psychological outcomes than those that conceptualized the role of the partner as active, neither approach yielded significantly better results for partner psychological outcomes, patient physical outcomes, and patient or partner relationship outcomes. Future research efforts may thus benefit from determining whether there are particular patient (e.g., type or stage of cancer, degree of functional disability/amount of caregiving required), partner (e.g., perceived disruption of the patient's illness, competing demands), and couple factors (e.g., length of relationship, whether or not the illness has a lasting effect on the couples' sexual intimacy), that might influence when it is more appropriate to conceptualize the partner's role as either supportive or active.

Choice of control group is also an important consideration for future couple-based intervention research. Although most studies compared a couple-based intervention to a usual care condition, it is unclear what “usual care” entailed and whether it differed from one medical center to the next. Moreover, only four studies [34; 40; 48; 49] compared a couples arm to a patient-only arm and only one [40] found significant differences between the two. Perhaps the couples arm was not sufficiently different from the patient-only arm in the other three studies. Identifying the “active-ingredients” of couple-based interventions, what makes them unique (beyond the inclusion of the partner), and if/how they provide added-value (beyond the value of focusing exclusively on the patient) requires further investigation if this field is to grow and move forward.

Although psychological outcomes were the focus of most interventions, the largest effect size found for patients (g = 0.31) was for physical outcomes and there was a trend (p<0.08) for interventions addressing communication to improve patient physical outcomes relative to those that did not. These findings are preliminary and in need of further corroboration as the couples' intervention literature expands and more researchers include physical outcomes as part of their assessment batteries. It is possible that teaching communication skills may facilitate the coordination of care between patients and their partners and help them to set realistic care goals and expectations.

None of the studies that we reviewed addressed cost issues, even though there is a need for studies that evaluate the cost-effectiveness of couple-based interventions as well as the relative cost-effectiveness of different modes of administration (i.e., in person, over the phone, internet). Similarly, no studies targeted lifestyle behavioral changes even though partners can engage in unhealthy behaviors (e.g., smoking) that can interfere with patient adherence to medical recommendations after a cancer diagnosis. Partners who model healthy behaviors for one another, acknowledge each other's successes, provide constructive feedback, and work together to overcome barriers may benefit in terms of increased self-efficacy and lasting behavioral change.

Overall, this review had a number of strengths. First, we included clear inclusion/exclusion criteria and used two independent coders. Second, we employed recommended meta-analytic techniques to account for heterogeneity and outliers. Third, we included carefully planned moderator analysis to allow for the identification of systematic differences among studies. Fourth, we examined quality of studies as a moderator of effect size. This review also had some limitations. We did not include unpublished studies. We thought that published, peer-reviewed studies would yield the strongest conclusions regarding treatment efficacy; however, we acknowledge that population effect sizes may be overestimated given the lack of publication of null findings. Moreover, while we examined three important QOL outcomes, couple-based interventions may have significant effects on other important variables that were not examined such as coping, caregiver burden, and the management of side effects (e.g., pain) as suggested by other published reviews in the caregiving [28] and chronic illness literatures [14].

In conclusion, couple-based interventions have beneficial effects on multiple aspects of QOL for both patients and their partners. Efforts are needed to strengthen future studies both conceptually and methodologically and to determine whether couple-based interventions can be integrated into clinical cancer care. We recognize that given the diversity of outcomes and intervention strategies, it may be difficult for clinicians to discern “best practice” recommendations based on this review. Indeed, the couples' intervention literature in cancer reflects the broader psychosocial intervention literature in terms of diversity in content (e.g., education, skills-training), format (e.g., in-person, over the phone) and characteristics (e.g., number and length of sessions and follow-up assessments). As Czaja and colleagues [69] have noted, the decomposition of psychosocial interventions for the purpose of identifying effective components is an important goal for the field of psycho-oncology. However the vast majority of couple-based interventions in cancer have only been published in the last decade and this young literature is not yet at that stage. By reviewing the current state of the literature on couple-based interventions in cancer and proposing future directions, we hope that this analysis will suggest ideas for future research that yields conceptual and methodological advances to bolster the efficacy of this promising treatment approach.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marisol Temech, who conducted the search and assisted with coding, and James Coyne who provided feedback on an earlier draft.

This research was supported by a career development award from the National Cancer Institute K07CA124668 (Hoda Badr, PhD, Principal Investigator) and a pilot grant awarded to Dr. Badr under P30 AG028741 (Albert Siu, MD, Principal Investigator).

References

- 1.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pistrang N, Barker C. The partner relationship in psychological response to breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:789–797. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00136-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson L, Bultz B, Speca M, St, Pierre M. Partners of cancer patients: Part 1. Impact, adjustment, and coping across the illness trajectory. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;18:39–57. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manne S, Badr H. Social relationships and cancer. In: Davila J, Sullivan K, editors. Support processes in intimate relationships. Oxford Press; 2010. pp. 240–264. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baider L, Kaufman B, Peretz T, Manor O, Ever-Hadani P, Kaplan De-Nour A. Mutuality of fate: Adaptation and psychological distress in cancer patients and their partners. In: Baider L, Cooper C, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer in the family. Chichester: Wiley; 1996. pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ell K, Nishimoto R, Mantell J, Hamovitch M. Longitudinal analysis of psychological adaptation among family members of patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:429. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(88)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(S11):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks H, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(1):1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott JL, Kayser K. A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer Journal. 2009;15(1):48–56. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean LM, Jones JM. A review of distress and its management in couples facing end-of-life cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(7):603–616. doi: 10.1002/pon.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baik OM, Adams KB. Improving the well being of couples facing cancer: A review of couples based psychosocial interventions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2010:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regan T, Lambert S, Girgis A, Kelly B, Kayser K, Turner J. Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? A systematic review. Bmc Cancer. 2012;12(1):279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi EM. Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 2010:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers SN, Ahad SA, Murphy AP. A structured review and theme analysis of papers published on ‘quality of life’ in head and neck cancer: 2000-2005. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(9):843–868. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measuring healthy days: Population assessment of health-related quality of life. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padilla GV, Ferrell B, Grant MM, Rhiner M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nursing. 1990;13(2):108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cella DF. Quality of life: Concepts and definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994;9(3):186–192. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutherland SE, Matthews DC. Conducting systematic reviews and creating clinical practice guidelines in dentistry: Lessons learned. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2004;135(6):747. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: A review of the current state of the science. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;62(3):251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhagen A, De Vet H, De Bie R, et al. The delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borenstein M, Hedges LV. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins J, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods. 2010;1(2):112–125. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Vol. 49. Sage Publications, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorin S, Krebs P, Badr H, Janke E, Jim HS, Spring B, Mohr D, Jacobsen P. A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):539–547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coyne JC, Thombs BD, Hagedoorn M. Ain't necessarily so: Review and critique of recent meta-analyses of behavioral medicine interventions in health psychology. Health Psychol. 2010;29(2):107. doi: 10.1037/a0017633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baucom DH, Kirby JS, Kelly JT. Couple-based interventions to assist partners with psychological and medical problems. In: Hahlweg K, Grawe M, Baucom DH, editors. Enhancing couples: The shape of couple therapy to come. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2009. pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comprehensive meta-analysis Book Comprehensive meta-analysis. City: Biostat; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen DN. Postmastectomy couple counseling: An outcome study of a structured treatment protocol. J Sex Marital Ther. 1983;9(4):266–275. doi: 10.1080/00926238308410913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, Rawl S, Monahan P, Burns D, Azzouz F, Reuille KM, Weinrich S, Koch M. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(4):752–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Jr, Robertson C, Mohler J. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: Nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94(6):1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalaitzi C, Papadopoulos VP, Michas K, Vlasis K, Skandalakis P, Filippou D. Combined brief psychosexual intervention after mastectomy: Effects on sexuality, body image, and psychological well-being. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96(3):235–240. doi: 10.1002/jso.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, Meek P, Lopez AM. Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nurs Res. 2007;56(1):44. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Budin WC, Hoskins CN, Haber J, Sherman DW, Maislin G, Cater JR, Cartwright-Alcarese F, Kowalski MO, McSherry CB, Fuerbach R. Breast cancer: Education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: A randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2008;57(3):199. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319496.67369.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinrichs N, Zimmermann T, Huber B, Herschbach P, Russell DW, Baucom DH. Cancer distress reduction with a couple-based skills training: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2011:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kayser K, Feldman BN, Borstelmann NA, Daniels AA. Effects of a randomized couple-based intervention on quality of life of breast cancer patients and their partners. Soc Work Res. 2010;34(1):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott J, Halford W, Ward B. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1122. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canada A, Neese L, Sui D, Schover L. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. J Urol. 2006;175(5):1825–1825. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, McKee DC, Edwards CL, Herman SH, Johnson LE, Colvin OM, McBride CM, Donattuci CF. Prostate cancer in african americans: Relationship of patient and partner self-efficacy to quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(5):433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCorkle R, Siefert M, Dowd M, Robinson J, Pickett M. Effects of advanced practice nursing on patient and spouse depressive symptoms, sexual function, and marital interaction after radical prostatectomy. Urol Nurs. 2007;27:65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manne SL, Nelson CJ, Kissane DW, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: A pilot study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, Montie JE, Sandler HM, Forman JD, Hussain M, Pienta KJ, Smith DC, Kershaw T. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, Fredman SJ, Stanton SE, Scott JL, Halford KW, Keefe FJ. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manne SL, Winkel G, Grana G, Ross S, Ostroff JS, Fox K, Miller E, Frazier T. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward SE, Serlin RC, Donovan HS, Ameringer SW, Hughes S, Pe-Romashko K, Wang KK. A randomized trial of a representational intervention for cancer pain: Does targeting the dyad make a difference? Health Psychol. 2009;28(5):588–597. doi: 10.1037/a0015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project genesis: Assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):1036. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, Hurwitz H, Moser B, Patterson E, Kim HJ. Partner assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(S18):4326–4338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuijer RG, Buunk BP, Majella De Jong G, Ybema JF, Sanderman R. Effects of a brief intervention program for patients with cancer and their partners on feelings of inequity, relationship quality, and psychological distress. Psychooncology. 2004;13:321–334. doi: 10.1002/pon.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, Dalton J, Baucom D, Pope MS, Knowles V, McKinstry E, Furstenberg C, Syrjala K. Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: A preliminary study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(3):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLean LM, Walton T, Rodin G, Esplen MJ, Jones JM. A couple-based intervention for patients and caregivers facing end-stage cancer: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Budin W, Hoskins C, Haber J, Sherman D, Maislin G, Cater J, Cartwright-Alcarese F, Kowalski M, McSherry C, Fuerbach R, Shukla S. Breast cancer: Education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: A randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2008;57(3):199–213. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319496.67369.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thoits PA. Social support as coping assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:416–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lepore SJ, Revenson TA. Social constraints on disclosure and adjustment to cancer. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007;1(1):313–333. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walster E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Badger T, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E. A case study of telephone interpersonal counseling for women with breast cancer and their partners. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(5):997–1003. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.997-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, Baucom DH, McBride CM, McKee DC, Sutton L, Carson K, Knowles V, Rumble M. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for lung cancer: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping - a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology. 1997;47:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kayser K. Enhancing dyadic coping during a time of crisis: A theory-based intervention with breast cancer patients and their partners. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. The psychology of couples and illness. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Northouse L, Mood D, Schafenacker A, Montie J, Sandler H, Forman J, Hussain M, Plienta K, Smith DAF, Kershaw T. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porter LS, Baucom DH, Keefe FJ, Patterson ES. Reactions to a partner-assisted emotional disclosure intervention: Direct observation and self-report of patient and partner communication. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G, Miller E, Ross S, Frazier T. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldigé CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):830–835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, Kwan K, Tanaka M, Lau DHM, Wun T, Welborn J, Meyers FJ, Christensen S. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fredman SJ, Baucom DH, Gremore TM, Castellani AM, Kallman TA, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Claire Dees E, Klauber-Demore N, Peppercorn J, Carey LA. Quantifying the recruitment challenges with couple-based interventions for cancer: Applications to early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(6):667–673. doi: 10.1002/pon.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kenny D, Kashy DA, Cook D. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]