Abstract

Implants that serve simultaneously as an osteoconductive matrix and as a device for local growth factor delivery may be required for optimal bone regeneration in some applications. In the present study, hollow hydroxyapatite (HA) microspheres (106–150 μm) in the form of three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds or individual (loose) microspheres were created using a glass conversion process. The capacity of the implants, with or without transforming growth factor- 1 (TGF- 1), to regenerate bone in a rat calvarial defect model was compared. The 3D scaffolds supported the proliferation and alkaline phosphatase activity of osteogenic MLO-A5 cells in vitro, showing their cytocompatibility. Release of TGF- 1 from the 3D scaffolds into phosphate-buffered saline ceased after 2–3 days when 30% of the growth factor was released. Bone regeneration in the 3D scaffolds and the individual microspheres increased with time from 6 to 12 weeks, but it was significantly higher (23%) in the individual microspheres than in the 3D scaffolds (15%) after 12 weeks. Loading with TGF-β1 (5 μg/defect) enhanced bone regeneration in the 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres after 6 weeks, but had little effect after 12 weeks. 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres with larger HA diameter (150–250 μm) showed better ability to regenerate bone. Based on these results, implants composed of hollow HA microspheres show promising potential as an osteoconductive matrix for local growth factor delivery in bone regeneration.

Keywords: bone regeneration, hollow hydroxyapatite microspheres, scaffolds, rat calvarial defect model, transforming growth factor- 1

1. Introduction

Bone repair is a complex cascade of biological events controlled by numerous cytokines and growth factors that provide signals at local injury sites, allowing progenitors and inflammatory cells to migrate and trigger healing processes. Implants that serve simultaneously as an osteoconductive matrix and as a device for local growth factor delivery may be required for optimal bone regeneration in some applications. The success of this strategy is highly dependent on the properties of the scaffold material (such as biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, and degradation rate) and on the scaffold architecture (such as porosity, pore size, and surface morphology).

Calcium phosphates such as hydroxyapatite (HA), Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, and beta-tricalcium phosphate ( -TCP), Ca3(PO4)2, composed of the same ions as the main mineral constituent of bone, are attractive implant materials for bone regeneration because they are biocompatible, osteoconductive, and produce no systemic toxicity or immunological reactions [1–4,]. These calcium phosphates also have a high affinity for proteins, such as the growth factors bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and transforming growth factor- (TGF- ) [5] which are known to stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [6]. Consequently, they can provide attractive carrier materials for growth factors and stem cells without a surface chemical modification that is sometimes required for polymers [7].

Synthetic HA has been prepared using a variety of methods, such as precipitation from solution [8], hydrothermal deposition [9], hydrolysis [10], mechanochemical synthesis [8], and sol–gel techniques [11]. Commonly, synthetic HA implants are formed by first preparing nano- or micro-sized HA particles and then forming them into the desired morphologies or architectures. HA in the form of porous scaffolds, substrates, or granules has been widely researched and used for biomedical applications, such as periodontal, oral, and maxillofacial surgery, and skeletal reconstruction [12]. When used as a carrier for growth factor delivery, the growth factor is commonly adsorbed or attached to the surface of the porous HA material [1–3, 13]. Consequently, the use of HA carriers with higher surface area could provide an advantage if the delivery of high doses of growth factors is required.

As a device for growth factor delivery, hollow HA microspheres with a mesoporous, high surface area shell wall can potentially provide greater capacity for more sustained release because the growth factor can be incorporated in the mesoporous shell as well as within the hollow core. While release of the growth factor from the shell could presumably be controlled by desorption, release of the growth factor from the hollow core could be controlled by diffusion through the mesoporous shell, which provides an additional mechanism for more sustained release.

Hollow HA microspheres with high surface area (>100 m2/g) and a mesoporous shell wall have been prepared by a glass conversion process, in which borate glass microspheres are converted in an aqueous phosphate solution near room temperature [14–16]. Hollow HA spheres of small diameter (~500 nm) have been prepared by a solution-based method [17], in which calcium and phosphate ions were reacted in a solution and aged at 60°C or 100°C for 1–7 days. Hollow HA spheres of larger diameter (1.5–2 mm) have been prepared by coating chitin microspheres with a composite layer of chitin and HA, followed by thermal decomposition of the chitin and sintering of the porous HA shell [18]. In our previous work, hollow HA microspheres (diameter in the range 106–250 m) were prepared by a glass conversion process described above, and their microstructures were characterized in detail [19]. In subsequent work, the ability of the hollow HA microspheres to serve as a device for controlled delivery of a model protein (bovine serum albumin) was evaluated [20].

The objective of the present work was to evaluate the ability of implants composed of hollow hydroxyapatite (HA) microspheres with a mesoporous shell wall to regenerate bone in a rat calvarial defect model, a widely used assay to evaluate bone regeneration in an osseous defect. Implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (106–150 m) thermally bonded into a porous three-dimensional (3D) construct, or individual hollow HA microspheres were evaluated after implantation for 6 and 12 weeks. The effects of loading the implants with TGF- 1 and larger HA microspheres size of the implants on bone regeneration were studied.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Fabrication of constructs composed of hollow HA microspheres

Two groups of implants were prepared and evaluated in the present work. One group consisted of porous scaffolds in which hollow HA microspheres were bonded at their contact points into a 3D network, while the other group was composed of the individual (loose) hollow HA microspheres. The 3D scaffolds were prepared by thermally bonding solid borate glass microspheres into a porous network, reacting the construct in an aqueous phosphate solution to convert the glass microspheres into hollow HA microspheres, and finally thermally treating the converted construct to improve its strength. The individual HA microspheres were prepared using the same process but without thermally bonding the starting glass microspheres.

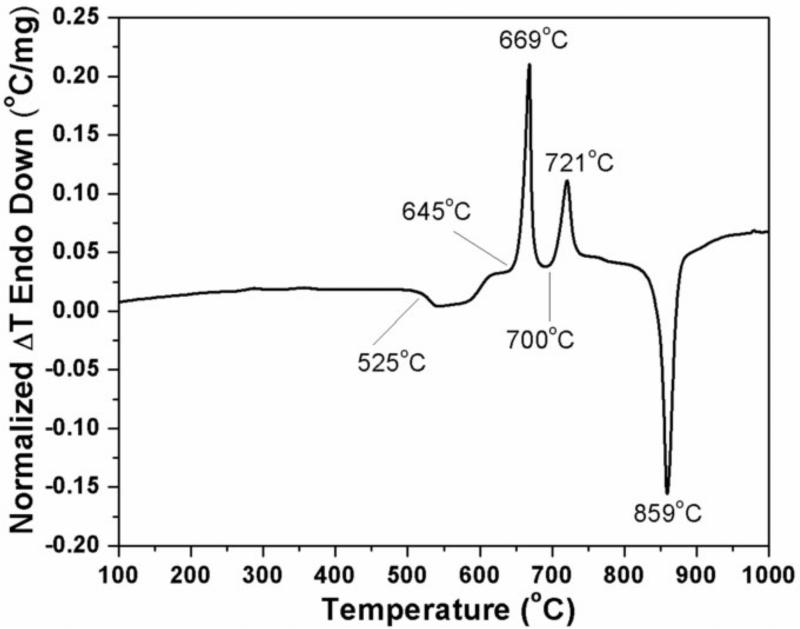

The starting borate glass (composition in wt%: 15CaO, 10.6 Li2O, 74.4 B2O3; designated CaLB3-15), was the same as that used in our previous work [19, 20]. Briefly, the glass was prepared by melting Reagent grade CaCO3, Li2CO3 and H3BO3 (Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA) in a Pt crucible at 1200°C for 45 min, and quenching the melt between cold stainless steel plates to prevent crystallization. Particles of size 106–150 m and 150–250 m were obtained by grinding the glass using a Spex mill (Model 8500, Spex SamplePrep LLC, Metuchen, N.J. USA), and sieving the particles through 140, 100, and 60 mesh stainless steel sieves. The glass particles were converted into microspheres at Mo-Sci Corp., Rolla, MO, USA, by allowing them to fall vertically through a heated tube furnace, as described in detail elsewhere [15]. Porous constructs with the shape of a cylinder (6 mm in diameter × 5 mm) for mechanical property evaluation, and with the shape of a disc (4.6 mm in diameter × 1.5 mm) for implantation, were prepared by pouring the glass microspheres into graphite molds, and sintering the system for 1 h at 560°C. The sintering conditions were selected on the basis of data for the glass transition and crystallization temperatures of the glass obtained from differential thermal analysis (DTA), coupled with trial and error. DTA (model DTA-7; Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA) was carried by heating the glass powder in air at 10°C/min to 1000°C.

3D scaffolds or individual HA microspheres were obtained by reacting the 3D glass constructs or the individual glass microspheres for 7 days in 0.02 M K2HPO4 solution (starting pH = 9.0) at 37°C. Those reaction conditions were based on our previous work [19, 20]. The converted materials were washed three times with distilled water, then twice with ethanol, dried overnight at room temperature, and heated for 5 h at 600°C to improve their strength.

2.2 Characterization of as-fabricated 3D scaffolds and individual HA microspheres

The microstructure of the surface and cross section of the 3D scaffolds and individual HA microspheres was examined using scanning electron microscopy, SEM (S4700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV and a working distance of 12 mm. Liquid extrusion porosimetry (Model LEP-100-A; Porous Materials Inc., Ithaca, NY) and the Archimedes method were used to measure the pore size distribution and the porosity, respectively, of the macropores in the 3D scaffolds. The HA microsphere shell in the 3D scaffolds had similar mesoporosity to the shell in the individual HA microspheres, which was characterized in previous work [19].

3D scaffolds (6 mm in diameter × 5 mm) composed of hollow HA microspheres (150–250 μm) were tested in compression at a rate of 0.5 mm/min in a mechanical testing machine (Model 4204, Instron Corp., High Wycombe, UK) to determine their strength. Five samples were tested, and the compressive strength was expressed as a mean ± standard deviation.

2.3 Response of cells to HA scaffolds

The cytocompatibility of the HA formed by converting the borate glass microspheres in aqueous phosphate solution was assessed by evaluating the ability of the 3D scaffolds to support the proliferation of murine MLO-A5 cells, a late osteoblast cell line developed by Bonewald and coworkers [21]. The cells, provided by Professor Lynda F. Bonewald, University of Missouri-Kansas City, were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 5% newborn calf serum (NCS) plus 100 U/ml penicillin on a collagen-coated plate (rat tail collagen type I; 0.15 mg/ml). All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 with the medium changed every 2 days.

MLO-A5 cells (30,000 cells) were seeded on disc-shaped 3D scaffolds (6 mm in diameter × 2 mm; HA microsphere diameter = 150–250 μm) and cultured in normal medium. The medium was replaced every 2 days. After incubation for 2, 4, and 6 days, the scaffolds were washed gently twice with PBS, and the cells were lysed using two freeze–thaw cycles (–80/37 °C) with 500 μl of 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Aliquots of the lysate were placed in a 96-well plate for spectrophotometric measurement of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (p-NPP) substrate as described elsewhere [22]. The values of ALP activity were normalized with respect to the total protein content obtained from the same cell lysate and expressed as nanomoles of pNP formed per microgram of protein per min. Total protein content was determined using a micro-BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnologies, Rockford, IL, USA), following the manufacturer's recommended procedure.

2.4 TGF-1 loading and release

3D scaffolds (discs) composed of hollow HA microspheres (106–150 μm) were loaded with transforming growth factor -1 (TGF- 1) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and used to study the release profile of TGF-β1 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Each scaffold (10 mg) was placed on a Teflon sheet and 20 μl of 1% solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) was dropped on the scaffold. The system was dried overnight to produce a BSA coating on the pore surface of the scaffold. The BSA-coated scaffold was loaded with TGF- 1 by dropping 10 μl of TGF-β1 solution (concentration = 5 ng per μl of solution) on the scaffold and applying a small vacuum to the system to replace the air in the HA microspheres with the TGF- 1 solution. After drying, the TGF-loaded scaffold was placed in PBS (2 scaffolds in 2 ml PBS). The samples were incubated while shaking at 37°C and at selected times (10 h, 1 d, 2 d, 3 d, 5 d, 7 d), 50 μl of the PBS was removed for testing. Control samples containing a known amount of TGF-β1 in a PBS buffer were also incubated at 37°C. The amount of TGF-β1 present in the release buffer was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (PeproTech). The concentrations of the unknown samples were quantified relative to a TGF-β1 standard curve run on the same plate.

2.5 Animals and surgery

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Missouri University of Science and Technology Animal Care and Use Committee, in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1985). The rat calvarial defect model was used in this study because it is a standard inexpensive assay for evaluating new bone formation in an osseous defect [23]. Thirty Sprague Dawley rats (3 months old; 350 ± 30g) were housed in the animal care facility and acclimated to diet, water, and housing. The rats were anesthetized with an intramuscularly injected mixture of ketamine and xylazine (0.15 μl per 100 g). The surgical area was shaved, scrubbed with 70% ethanol, and then draped. With sterile instruments and aseptic technique, a cranial skin incision was sharply made in an anterior to posterior direction along the midline. The subcutaneous tissue, musculature and periosteum were dissected and reflected to expose the calvarium. Bilateral full-thickness defects 4.6 mm in diameter were created in the central area of each parietal bone using a 4.6 mm outer diameter trephine attached to an electric drill. The sites were constantly irrigated with sterile PBS to prevent overheating of the bone margins and to remove the bone debris.

The calvarial defects were implanted with 6 groups composed of hollow HA microspheres:

3D scaffolds (4.6 mm in diameter × 1.5 mm) composed of 106–150 m microspheres;

individual microspheres (106–150 m);

3D scaffolds composed of 106–150 m microspheres loaded with TGF- 1 (5 g/defect);

individual microspheres (106–150 m) loaded with TGF- 1 (5 g/defect);

3D scaffolds composed of 150–250 m microspheres;

individual microspheres (150–250 m)

The 3D scaffolds were loaded with TGF- 1 using the method described previously. Loading the individual HA microspheres was performed by weighing out the required mass of microspheres (equal to the mass of a 3D scaffold), placing the microspheres in a centrifuge tube, and coating the pore surface by dropping the BSA solution onto the microspheres, using the same volume of BSA solution used for the 3D scaffolds. After drying, 10 μl of the TGF- 1 solution (the same volume used for each scaffold) was dropped onto the microspheres and a small vacuum was applied to the system to replace the air in the HA microspheres with the TGF- 1 solution.

The rat calvarial defects were randomly implanted with 5 implants per group, but mixing of implants with or without TGF- 1 in the same animal was avoided. Defects left empty served as negative controls. 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres (106–150 μm) (6 and 12 weeks), empty defects (6 and 12 weeks), plus the 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres (150–250 μm) (12 weeks) were assigned randomly to 20 rats. The 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres (106–150 μm) loaded with TGF- 1 (6 and 12 weeks) were assigned randomly to 10 rats. Each animal received an intramuscular injection of ~200 μl penicillin and ~200 μl buprenorphine post-surgery. The animals were monitored daily for condition of the surgical wound, food intake, activity and clinical signs of infection. After 6 or 12 weeks, the animals were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation, and the calvarial defect sites with surrounding bone and soft tissue were harvested. Those implantation times were chosen based on our previous work that showed adequate new bone formation in bioactive glass scaffolds implanted in rat calvarial defect for 12 weeks [24].

2.6 Histology

The calvarial samples consisting of the defect sites with surrounding bone and soft tissue were washed with PBS and fixed in 10% formalin solution for 5 days. The fixed tissue samples were each cut into two parts; half of each sample was for paraffin embedding and the other half for methyl methacrylate embedding. The samples for paraffin sections were decalcified for 4 weeks in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (14 wt%) under mild agitation on a rocking plate. After the samples were dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in paraffin using standard histological techniques, 5 μm thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The undecalcified samples were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol solutions, and embedded in methyl methacrylate. Sections were ground to a thickness of 30–40μm using a micro grinding system (EXAKT 400CS, Norderstedt, Germany), and stained using the von Kossa technique to observe mineralization.

2.7 Histomorphometric analysis

Stained sections were examined in a transmitted light microscope (Model BX51; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) fitted with a digital color camera (Model DP71; Olympus). Images were analyzed on a computer using the Image J software (Image J 1.44, National Institutes of Health, USA). Sections stained with H&E were used to analyze the percentage of new bone formed within the defect. The newly formed bone was identified by outlining the edge of the defect, with the presence of original and new bone being identified by lamellar and woven bone, respectively. The total defect area was measured from one edge of the old calvarial bone, including the entire implant and tissue within it, to the other edge of the old bone. The newly formed bone within this area was then outlined and measured; the amount of new bone was expressed as a percentage of the total defect area.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Cell culture and TGF-β1 release experiments (n = 3) were run in triplicate, and the data are presented as a mean ± standard deviation (sd). Measurements (n = 5) of percentage new bone formed in the implants are expressed as a mean ± sd. Analysis for differences between groups was performed using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA by ranks; differences were considered significant for p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Microstructure and properties of implants

The DTA pattern (Fig. 1) of the starting borate glass used to prepare the HA implants showed an onset of glass transition at 525°C, and two crystallization events with onset temperatures of 645°C and 700°C, respectively. Since one objective of the scaffold fabrication process was to bond the glass spheres into a 3D network by viscous flow sintering without crystallizing the glass, the DTA pattern indicated a sintering temperature in the range 525–645°C. Experiments showed that sintering for 1 h at 560°C provided adequate 3D scaffold strength for subsequent use without measurable crystallization of the glass; consequently, those sintering conditions were used to prepare 3D constructs of the glass microspheres.

Fig. 1.

DTA pattern of borate (CaLB3-15) glass microspheres used for the creation of 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres and individual HA microspheres by the glass conversion process.

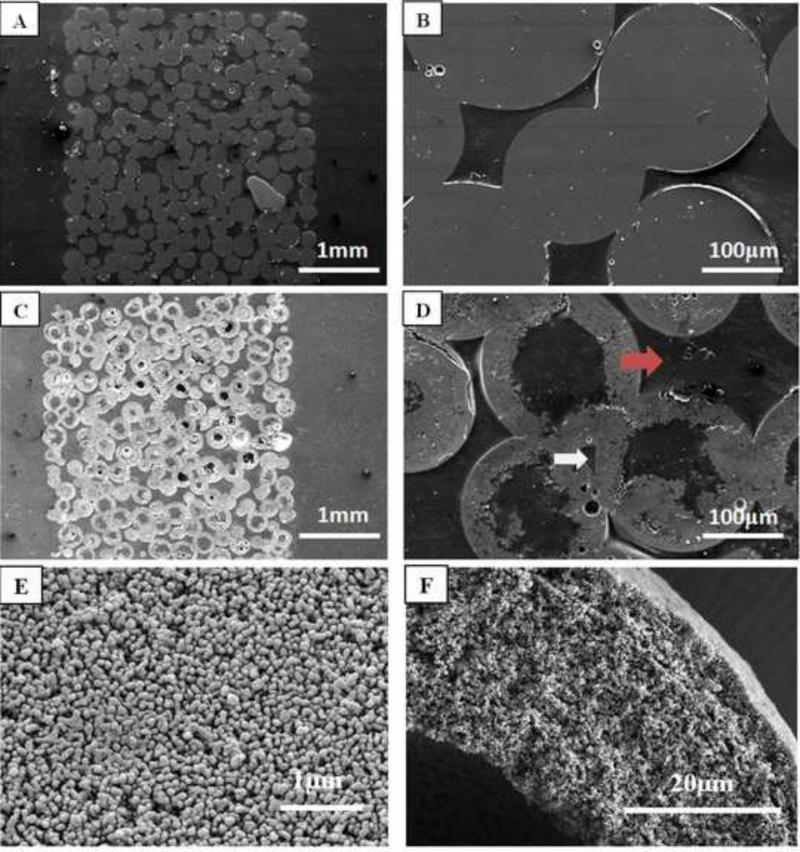

Figure 2 shows SEM images of a 3D construct composed of thermally-bonded borate glass microspheres (Fig. 2a, b) and a 3D scaffold composed of hollow HA microspheres (150–250 μm) formed by converting the glass construct in K2HPO4 solution (Fig. 2c, d). The conversion of the glass microspheres to HA was pseudomorphic, with little change in the external dimensions of the glass microspheres (or the 3D construct), and the HA microspheres remained bonded together in a 3D network. The cross section confirmed that the HA microspheres in the 3D scaffolds were hollow. (Because each HA microsphere is sectioned at a different depth along its diameter, the hollow core diameter can vary in the planar section). The individual hollow HA microspheres were similar to those prepared and characterized in detail in our previous work [19, 20]. High magnification SEM showed no observable differences in microstructure between the individual HA microspheres and the HA microspheres in the 3D scaffolds (Fig. 2e, f). The ratio of the hollow core diameter to the external diameter of the HA microspheres was 0.61 ± 0.03. The shell of the hollow HA microspheres was 60% porous, with pores of average size = 10 nm (measured using nitrogen adsorption).

Fig. 2.

(A,B) Cross sections of 3D construct composed borate glass microspheres (150–250μm); (C,D) cross sections of 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres (150–250 μm) formed by the glass conversion process; (E,F) SEM images of the surface and cross section, respectively, of the HA microsphere shell. Arrows in (D) indicate macropores of different sizes in the 3D scaffolds.

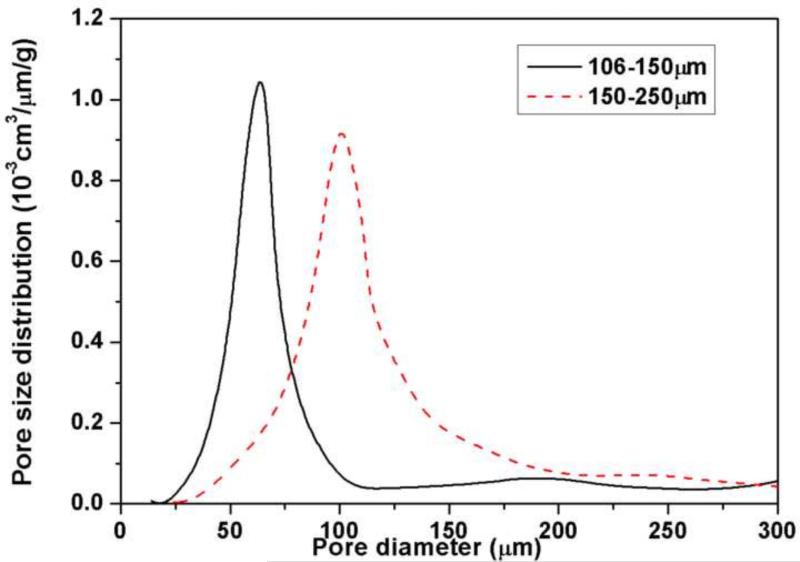

The porosity in the 3D scaffolds consisted of macropores between the HA microspheres (arrows) and mesopores in the HA shell, in addition to the porosity in the hollow core of the microspheres (Fig. 2). Macropores and mesopores are defined as pores of size >50 nm and 2–50 nm, respectively [25]. The volume of the macropores determined by the Archimedes method was 34 ± 3% for scaffolds composed of 106–150 m microspheres, and 38 ± 4% for the scaffolds composed of 150–250 m microspheres. Porosimetry showed that the macropores in the 3D scaffolds composed of 106–150 m microspheres had sizes in the range 10 to 100 m, with an average of 65 m (Fig. 3). In comparison, scaffolds composed of 150–250 m microspheres had macropore sizes in the range 30–150 m, with an average of 100 m.

Fig. 3.

Size distribution of macropores in 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres of diameter 106–150 m and 150–250 m, as determined by liquid extrusion porosimetry.

The compressive strength of the 3D scaffolds (150–250 m microspheres) was 1.6 ± 0.4 MPa. For comparison, the rupture strength of the individual hollow HA microspheres (200–250 μm), determined in previous work [19], was 17 ± 8 MPa. The characteristics of the 3D scaffolds and the individual HA microspheres are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Characteristics of HA implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (3D scaffolds and individual microspheres) used in this study.

| Implant | Microsphere diameter (μm) | Interconnected macroporosity (%) | % of macropores >100 μm | Compressive strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D scaffold | 106–150 | 34 ± 3 | 10 | |

| 150–250 | 38 ± 4 | 35 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Individual microspheres | 106–150 | |||

| 150–250 | 17 ± 8# | |||

Hollow HA microspheres:

Hollow core diameter/microsphere diameter = 0.61 ± 0.03

Porosity of shell wall = 60%

Surface area = 19 m2/g

Average pore size of shell wall = 10 nm

Rupture strength; 200–250 μm

3.2 Cytocompatibility of HA scaffolds

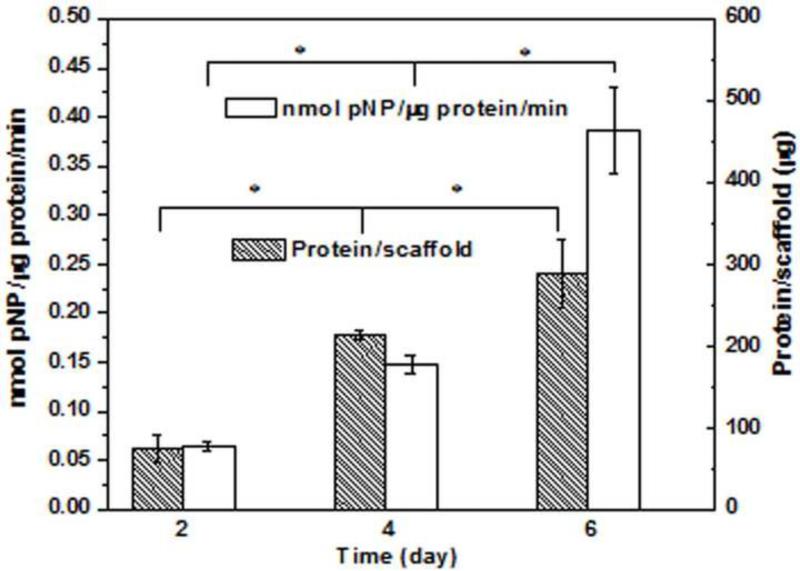

Results of the quantitative assay of total protein and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in MLO-A5 cell lysates recovered from the 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres (150–250 μm) after incubation times of 2, 4, and 6 days are shown in Fig. 4. The amount of protein recovered from the scaffolds showed an increase in cell proliferation during the 6 day incubation, a finding that complements SEM images of the cell morphology on the scaffolds (results not shown). The ALP activity increased during the 6 day incubation, which indicated that the cells were able to carry out an osteogenic function in the scaffolds. In general, the increase in cell proliferation and ALP activity during the six-day incubation confirmed the cytocompatibility of the 3D scaffolds and individual HA microspheres created in this work.

Fig. 4.

Protein amount and alkaline phosphatase activity of MLO-A5 cells cultured for 2, 4, and 6 days on 3D scaffolds (discs) composed of hollow HA microspheres (150–250 μm). Mean ± SD; n=3. (*significant difference between groups; p<0.05.)

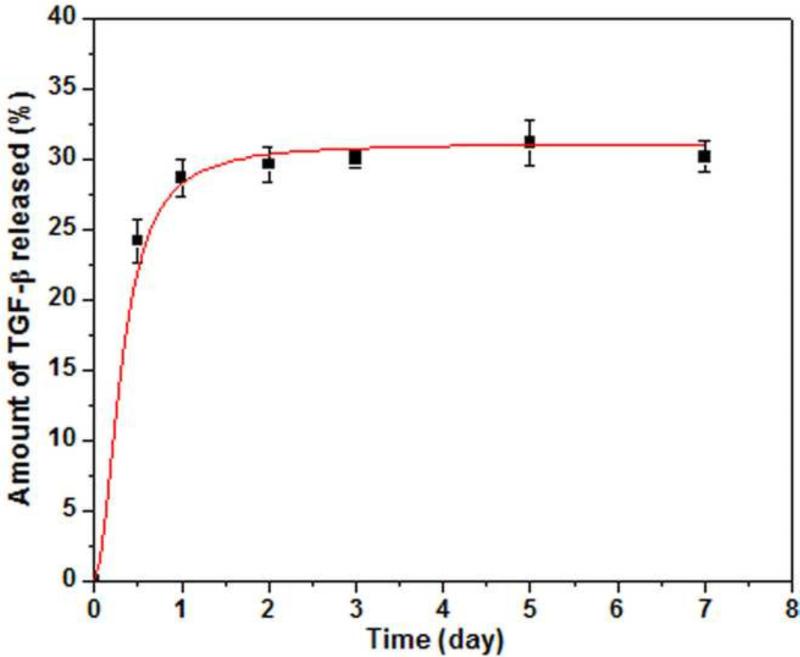

3.4 Release of TGF-β1 from hollow HA microspheres

Figure 5 shows the release profile of TGF-β1 from the 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres (106–150 m) into PBS. The release was initially rapid, with 25% of the TGF- 1 initially loaded into the scaffold released during the first 12 hours. This initial burst release was followed a slower release rate over the next 2 days, after which the release almost ceased. After 7 days, the total amount of TGF-β1 released into the PBS was 30% of the original amount loaded into the microspheres. The release of TGF- 1 from the individual HA microspheres was not measured. However, since the method of loading the individual microspheres with TGF- 1 was similar to that for the 3D scaffolds, the release profile is not expected to be very different for the two systems.

Fig. 5.

Amount of TGF-β1 released from 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres (diameter = 106–150μm) into PBS as a function of time.

3.5 Bone regeneration

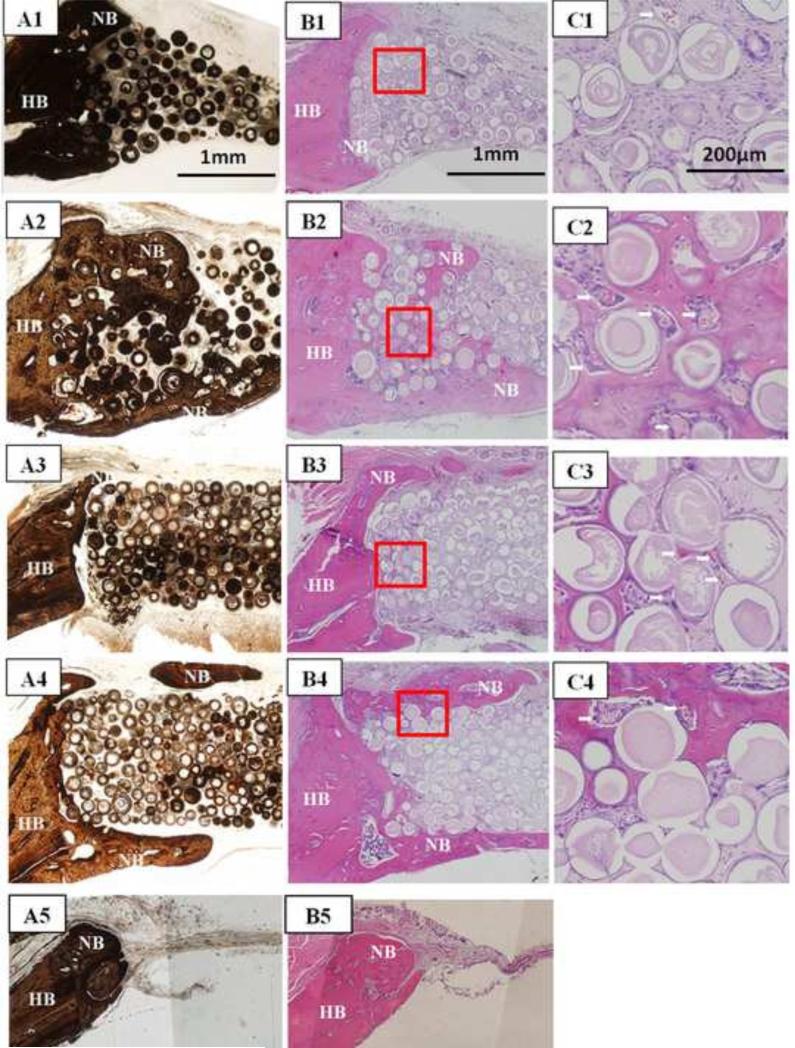

H&E and von Kossa stained sections of HA implants composed of 3D scaffolds and individual HA microspheres without TGF- 1, and for those two groups of implants loaded with TGF– 1 (5μg/defect) are shown in Fig. 6. The implantation time in rat calvarial defects was 6 weeks, and the implants were composed of 106–150 m microspheres. For both groups of implants without TGF-β1, bone regeneration was limited mainly to the edges of the implants, with some bone bridging along the top and bottom of the implants (Fig. 6A1–C1; A3–C3). The majority of the defect was filled with fibrous connective tissue (light blue in H&E stained sections). Total bone regeneration in the individual microspheres (12%) was significantly higher than in the 3D scaffolds (3%) (Fig. 7).

Fig 6.

Von Kossa stained sections (A1–A4) and H&E stained sections (B1–C4) of implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (106–150 m) after 6 weeks in rat calvarial defects: individual HA microspheres without TGF- 1 (A1–C1) and with TGF- 1 (A2–C2); 3D scaffolds without TGF- 1 (A3–C3) and with TGF- 1 (A4–C4); von Kossa and H&E stained sections of the empty defects (A5, B5) are shown for comparison. Arrows in C1–C4 indicate blood vessels.

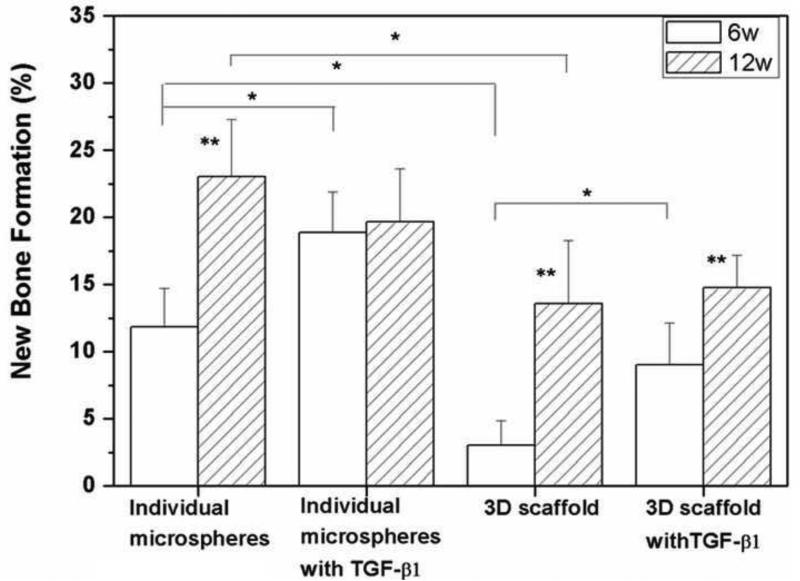

Fig. 7.

Percent new bone formation in 3D scaffolds and individual HA microspheres (106–150 m) after 6 and 12 weeks in rat calvarial defects. (Mean ± sd; n=5. *significant difference between groups; **significant increase compared to six-week value for the same group; p<0.05).

Bone regeneration was significantly enhanced in both implant groups loaded with TGF- 1 after the six-week implantation (Fig. 6A2–C2; A4–C4); bone regeneration increased from 3% to 9% in the 3D scaffolds and from 12% to 19% in the individual microspheres (Fig. 7). For both groups, new bone formation was observed at the edges, with bone bridging along the top and bottom of the implants, as well as within the implants. In the 3D scaffolds, most new bone formed along the top and bottom of the implants, with a smaller amount of new bone infiltrating the edges of the implant. In comparison, for the individual microspheres, most new bone formed within the implant, and new bone infiltrated 1–2 mm into the edges of the implant. Some of the individual HA microspheres were surrounded by newly formed bone, and they were tightly connected with new bone (Fig. 6C2). Blood vessels were observed in the tissue between the HA microspheres (Fig. 6C2, C4; arrows). H&E and von Kossa stained sections of empty defects after implantation for 6 weeks are shown in Fig. 6A5, B5. The defect was almost filled with soft connective tissue, and bone regeneration was observed only at the edge of the defects along the native dura mater.

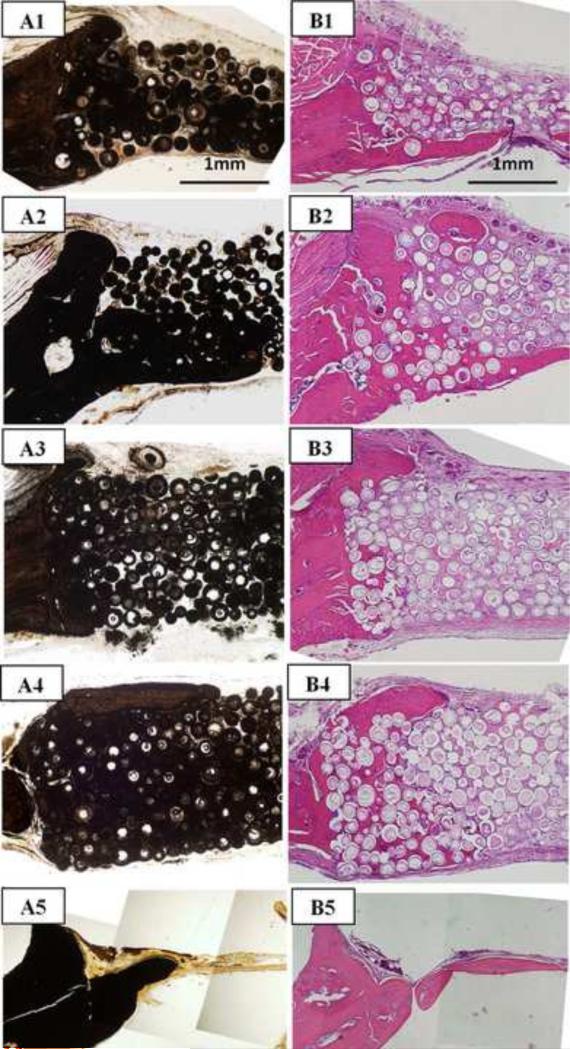

Bone regeneration increased significantly in both groups of implants (without TGF– 1) as the implantation time increased from 6 to 12 weeks (Fig. 8A1, B1; A3, B3). New bone infiltrated the implants from the edges and also formed on the dural (bottom) side of the implants. Increase in the implantation time from 6 to 12 weeks resulted in an increase in bone regeneration, from 3 to 13% for the 3D scaffolds and from 12% to 23% for the individual microspheres (see Fig. 7). Twelve weeks postimplantation, the percent new bone formed in each implant group loaded with TGF- 1 was not significantly different from that in the same implant group without TGF-β1. New bone formation in the empty defects (Fig. 8A5, B5) was limited to ~1mm from the edge of the defect, and the thickness of the new bone in the stained section was only 200 μm.

Fig. 8.

(Left) von Kossa and (right) H&E stained sections of implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (106–150 m) after 12 weeks in rat calvarial defects: individual hollow HA microspheres without TGF- 1 (A1,B1) and with TGF- 1 (A2, B2); 3D scaffolds without TGF- 1 (A3,B3) and with TGF- 1 (A4,B4); stained sections of the empty defects are shown for comparison (A5,B5).

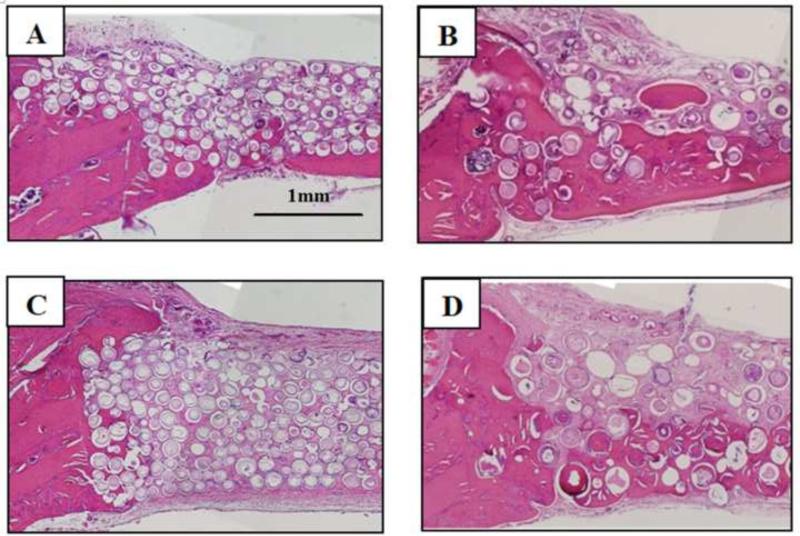

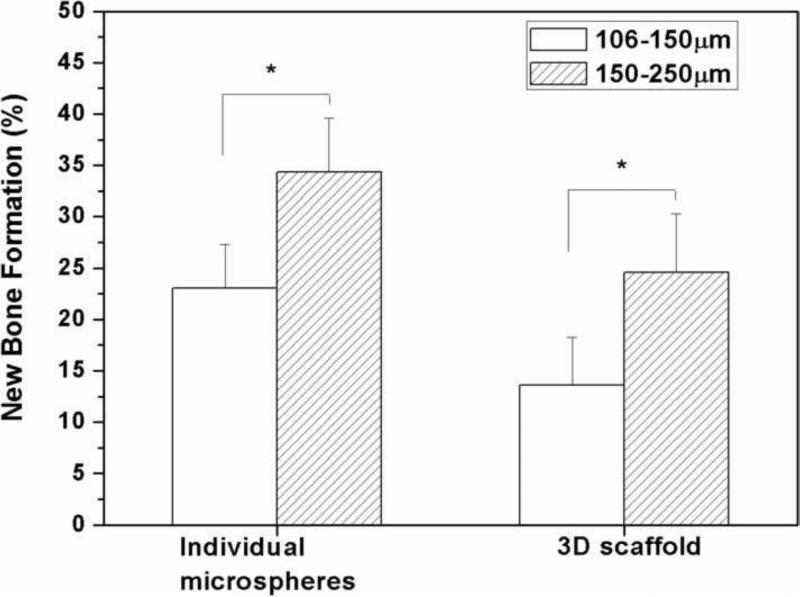

Bone regeneration in the 3D scaffolds and individual microspheres without TGF-β1 increased significantly as the diameter of the HA microspheres was increased from 106–150 m to 150–250 m (Fig. 9, 10). Twelve weeks postimplantation, bone regeneration increased from 15% to 25% in the 3D scaffolds and from 23% to 35% in the individual microspheres as the HA microsphere size was increased. Bone growth was enhanced at the edges and on the dural side of both groups of implants (Fig. 9B, D).

Fig. 9.

H&E stained sections of implants composed of hollow HA microspheres with two different microsphere diameter after implantation for 12 weeks in rat calvarial defects: individual microspheres of diameter 106–150 μm (A) and 150–250 μm (B); 3D scaffold composed of microspheres of diameter 106–150 μm (C) and 150–250 μm (D).

Fig. 10.

Percent new bone formation in implants composed of hollow HA microspheres of diameter 106–150 m or 150–250 m after 12 weeks in rat calvarial defects. (Mean ± sd; n=5. *significant difference between groups; p<0.05).

4. Discussion

The results indicate that porous 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres with a mesoporous shell wall or the individual (loose) HA microspheres themselves can provide a promising matrix for bone regeneration. In addition to being biocompatible, the 3D scaffolds or individual microspheres can simultaneously provide the combined function of an osteoconductive matrix and a device for local growth factor delivery.

Three-dimensional scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres or individual hollow HA microspheres were created using a glass conversion technique [16], resulting in a unique combination of characteristics that cannot be readily achieved by known methods. By thermally bonding solid borate glass microspheres into the desired macroporous architecture and 3D geometry, the glass constructs were converted into 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres with the same external geometry and macroporosity as the original glass construct (Fig. 2). In addition to a matrix of interconnected macropores to support bone ingrowth and integration, the 3D scaffolds consisted of high surface area, nanostructured HA known to be favorable for protein adsorption, osteogenic cell differentiation, and nutrient transport [26, 27]. The hollow core combined with the high surface area, mesoporous shell of the HA microspheres provided features for growth factor loading and release. Except for the absence of a well-defined 3D geometry, individual hollow HA microspheres provided the benefits of the 3D scaffolds in addition to the potential benefit of implantation into irregular-shaped defects.

The percent new bone formed in HA implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (3D scaffolds and individual microspheres) with or without TGF- 1 implanted in rat calvarial defect for 6 or 12 weeks are summarized in Table II. When implanted in rat calvarial defects, the 3D scaffold maintained its structural integrity throughout the twelve-week implantation period (Fig. 8B2, B4), indicating its ability to maintain the shape of the defect. The individual HA microspheres were also well contained in the defect sites, but migration or loss of microspheres from the defect site was apparent. H&E stained sections (Fig. 6) showed significant cellular infiltration throughout all the implants, as well as significant extracellular matrix formation, indicating good scaffolding properties of the implants. However, new bone formation (NB) in the defects was observed mainly at the edge of the implants adjacent to the host bone (HB) and at the bottom (dural) side of the implants (Fig. 6). This pattern of bone regeneration presumably resulted from contact of the edge of the implant with the host bone, making this area easily accessible to osteogenic cells and blood supply, and from contact of the bottom of the implant with the dura mater which also contains osteogenic cells.

Table II.

Summary of percent new bone formed in HA implants composed of hollow HA microspheres (3D scaffolds and individual microspheres) with or without TGF- 1 implanted in rat calvarial defects for 6 or 12 weeks.

| Implant | Microsphere diameter (μm) | TGF- 1 loading/defect | % new bone formed |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | 12 weeks | |||

| 3D scaffold | 106–150 | – | 3 ± 2 | 13 ± 5 |

| 106–150 | 5μg | 9 ± 4 | 15 ± 3 | |

| 150–250 | – | 25 ± 4 | ||

| Individual microspheres | 106–150 | – | 12 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 |

| 106–150 | 5μg | 19 ± 3 | 19 ± 4 | |

| 150–250 | – | 35 ± 5 | ||

When implanted in rat calvarial defects for 6 or 12 weeks, the individual HA microspheres had a greater capacity to support bone regeneration than the 3D scaffolds composed of HA microspheres with the same diameter; this trend was independent of the HA microsphere diameters used in this work (106–150 m or 150–250 m) (Fig. 7, 10). The lower bone formation in the 3D scaffolds was presumably limited by the pore size and pore interconnectivity of the scaffold which contained a large fraction of pores smaller than 100 μm (particularly for the 3D scaffold composed of 106–150 m microspheres) (Fig. 3; Table I). In the literature, a pore size of 100 μm has been considered to be the minimum requirement for supporting tissue ingrowth [28] but pores of size >300 μm may be required for enhanced bone ingrowth and formation of capillaries [29]. Enlarging the macropore size of the 3D scaffold, by using microspheres of larger diameter or pore-forming (porogen) particles, might be necessary to better support bone regeneration. In comparison, implants composed of individual HA microspheres showed a greater capacity to support bone regeneration, which might be attributed to the ease with which the microspheres could adjust their positions in response to a stress, thereby enabling changes in the pore sizes to accommodate cell infiltration.

TGF- 1 was selected as the growth factor in this study because it has been reported to promote bone growth when delivered locally or administered systematically [30, 31], in addition to our previous experience in assaying TGF-β1. Our results showed that loading the implants with TGF- 1 significantly enhanced bone regeneration at 6 weeks (Fig. 7), which is consistent with the observations of those studies. The enhancement of bone regeneration by TGF- 1 loading was observed for both the 3D scaffolds and the individual HA microspheres.

The percent new bone continued to increase significantly with time in all groups except for the individual HA microspheres loaded with TGF-β1. However, the difference in bone regeneration between corresponding groups with or without TGF-β1 loading became insignificant 12 weeks postimplantation (Fig. 7). This might be due to the non-optimized release profile of TGF-β1 from the HA microspheres. The in vitro results (Fig. 5) showed a significant burst release of TGF– 1 in the first 12 hours, and 30% of the TGF- 1 initially loaded in the microspheres was released within 2 days. Thereafter, the release of TGF-β1 almost ceased, although ~70% of the initial TGF-β1 was still retained by the implants. HA is known for its high affinity for various proteins [32], and the release of adsorbed proteins is often dependent on the resorption of HA in vivo [33, 34]. In the present work, measureable resorption of HA was not observed within the twelve-week implantation period. It is therefore likely that TGF-β1 was not continuously released into the bone defect, which could account for the absence of a significant difference in bone regeneration after 12 weeks.

We are currently studying bone regeneration in hollow HA microspheres loaded with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), which is known to be a more potent growth factor than TGF- 1 for bone regeneration. Our preliminary results have shown that when implanted in rat calvarial defects for 6 weeks, hollow HA microspheres loaded with BMP-2 (1 μg/defect) supported significantly greater bone regeneration when compared to similar HA microspheres loaded with TGF- 1 (5 μg/defect used in the present study). The results of our current work will be reported in a future publication.

5. Conclusion

Three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds composed of hollow hydroxyapatite (HA) microspheres with a mesoporous shell wall and individual hollow HA microspheres were created by a glass conversion process and evaluated for their ability to regenerate bone in rat calvarial defects. Bone regeneration increased significantly in both groups of implants with an increase in implantation time from 6 to 12 weeks. Bone regeneration was significantly higher in the implants composed of individual HA microspheres than in the 3D scaffolds after both implantation times. Loading the implants with TGF- (5 g/defect) significantly enhanced bone regeneration in both groups of implants 6 weeks postimplantation, but showed little effect in enhancing bone regeneration 12 weeks postimplantation. Increasing the HA microsphere diameter in the implants from 106–150 m to 150–250 m resulted in a significant increase in bone regeneration. Individual hollow HA microspheres or 3D scaffolds composed of hollow HA microspheres loaded with a suitable growth factor could provide promising implants for bone regeneration.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Grant # 1R15DE018251-01, and by the Center for Bone and Tissue Repair and Regeneration, Missouri S&T.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Giannoudis P, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury. 2005;36:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeGeros RZ. Properties of osteoconductive biomaterials: calcium phosphates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:81–98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucholz R. Nonallograft osteoconductive bone graft substitutes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:44–52. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Zhang L, Chen X, Yang G, Zhang L, Gao C, et al. Trace element-incorporating octacalcium phosphate porous beads via polypeptide-assisted nanocrystal self-assembly for potential applications in osteogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:1586–96. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhé P, Kroese-Deutman H, Wolke J, Spauwen P, Jansen J. Bone inductive properties of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement implants in cranial defects in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman JR, Daluiski A, Einhorn TA. The role of growth factors in the repair of bone. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2002;84:1032–44. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200206000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hing K. Bioceramic bone graft substitutes: influence of porosity and chemistry. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2005;2:184–99. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeri MR, Afshar A, Ghorbani M, Ehsani N, Sorrell CC. The wet precipitation process of hydroxyapatite. Mater Lett. 2003;57:4064–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masahiro Y, Hiroyuki S, Kengo O, Koji I. Hydrothermal synthesis of biocompatible whiskers. J Mater Sci. 1994;29:3399–402. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih WJ, Chen YF, Wang MC, Hon MH. Crystal growth and morphology of the nano-sized hydroxyapatite powders synthesized from CaHPO4.2H2O and CaCO3 by hydrolysis method. J Cryst Growth. 2004;270:211–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim IS, Kumta PN. Sol-gel synthesis and characterization of nanostructured hydroxyapatite. Mater Sci Eng B. 2004;111:232–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlovskii VP, Komlev VS, Barinov SM. Hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite-based ceramics. Inorg Mater. 2002;38:973–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schek R, Wilke E, Hollister S, Krebsbach P. Combined use of designed scaffolds and adenoviral gene therapy for skeletal tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day DE, Conzone SA. Method for preparing porous shells or gels from glass particles. 2002 Mar 19; US Patent No. 6,358,531.

- 15.Day DE, White JE, Bown RF, McMenamin KD. Transformation of borate glasses into biologically useful materials. Glass Technol. 2003;44:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conzone SD, Day DE. Preparation and properties of porous microspheres made from borate glass. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2009;88:531–42. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia W, Grandfield K, Schwenke A, Engqvist H. Synthesis and release of trace elements form hollow and porous hydroxyapatite spheres. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:305610. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/30/305610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng Q, Ming L, Jiang CX, Feng B, Qu SX, Weng J. Preparation and characterization of hydroxyapatite microspheres with hollow core and mesoporous shell. Key Eng Mater. 2006;309–311:65–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu H, Rahaman MN, Day DE. Effect of process variables on the microstructure of hollow hydroxyapatite microspheres prepared by a glass conversion process. J Am Ceram Soc. 2010;93:3116–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.03833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu H, Rahaman MN, Day DE, Brown RF. Hollow hydroxyapatite microspheres as a device for controlled delivery of proteins. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22:579–91. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato Y, Boskey A, Spevak L, Dallas M, Hori M, Bonewald LF. Establishment of an osteoid preosteocyte-like cell MLO-A5 that spontaneously mineralizes in culture. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1622–33. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barragan-Adjemian C, Nicolella D, Dusevich V, Dallas MR, Eick JD, Bonewald LF. Mechanism by which MLO-A5 late osteoblasts/early osteocytes mineralize in culture: Similarities with mineralization of lamellar bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79:340–53. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Glimcher MJ, Mah J, Zhou HY, Salih E. Expression of bone microsomal casein kinase II, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin during the repair of calvarial defects. Bone. 1998;22:621–8. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bi L, Jung S, Day D, Neidig K, Dusevich V, Eick D, Bonewald L. Evaluation of bone regeneration, angiogenesis, and hydroxyapatite conversion in critical-sized rat calvarial defects implanted with bioactive glass scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34272. in press. DOI: 10.1002/jbm.a.34272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sing KSW, Everett DH, Haul RAW, Moscou L, Pierotti RW, Rouquérol J, Siemieniewska T. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl Chem. 1985;57:603–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin T, Su C, Chang C. Stereomorphologic observation of bone tissue response to hydroxyapatite using SEM with the EDTA-KOH method. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;36:91–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199707)36:1<91::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai N, Niwa S, Sato M, Sato Y, Suwa Y, Ichihara I. Bone formation by cells from femurs cultured among three-dimensionally arranged hydroxyapatite granules. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;37:1–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199710)37:1<1::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulbert SF, Young FA, Matthews RS, Klawitter JJ, Talbert CD, Stelling FH. Potential of ceramic materials as permanently implantable skeletal prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1970;4:433–56. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820040309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Potential of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lind M, Schumacker B, Soballe K, Keller J, Melsen F, Bunger C. Transforming growth factor-β enhances fracture healing in rabbit tibiae. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:553–6. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck LS, Amento EP, Xu Y, DeGuzman L, Lee WP, Nguyen T, Gillett NA. TGF-β1 induces bone closure of skull defects: Temporal dynamics of bone formation in defects exposed to rhTGF-β1. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:753–61. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wen HB, Hippensteel EA, Li P. Protein adsorption property of a biomimetic apatite coating. Key Eng Mater. 2005;284–286:403–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piskounova S, Forsgren J, Brohede U, Engqvist H, Stromme M. In vitro characterization of bioactive titanium dioxide/hydroxyapatite surfaces functionalized with BMP-2. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;91:780–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suárez-González D, Barnhart K, Migneco F, Flanagan C, Hollister SJ, Murphy WL. Controllable mineral coatings on PCL scaffolds as carriers for growth factor release. Biomaterials. 2012;33:713–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]