Abstract

Our previous study demonstrated that increased Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel activity played a key role in the normal adaptation of reduced myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnancy. The present study tested the hypothesis that chronic hypoxia during gestation inhibits pregnancy-induced upregulation of BKCa channel function in uterine arteries. Resistance-sized uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant and near-term pregnant sheep maintained at sea level (≈300 m) or exposed to high-altitude (3801 m) hypoxia for 110 days. Hypoxia during gestation significantly inhibited pregnancy-induced upregulation of BKCa channel activity and suppressed BKCa channel current density in pregnant uterine arteries. This was mediated by a selective downregulation of BKCa channel β1 subunit in the uterine arteries. In accordance, hypoxia abrogated the role of the BKCa channel in regulating pressure-induced myogenic tone of uterine arteries that was significantly elevated in pregnant animals acclimatized to chronic hypoxia. In addition, hypoxia abolished the steroid hormone-mediated increase in the β1 subunit and BKCa channel current density observed in nonpregnant uterine arteries. Although the activation of protein kinase C inhibited BKCa channel current density in pregnant uterine arteries of normoxic sheep, this effect was ablated in the hypoxic animals. The results demonstrate that selectively targeting BKCa channel β1 subunit plays a critical role in the maladaption of uteroplacental circulation caused by chronic hypoxia, which contributes to the increased incidence of preeclampsia and fetal intrauterine growth restriction associated with gestational hypoxia.

Keywords: hypoxia, uterine artery, pregnancy, BKCa channel, myogenic tone, steroids

Uterine blood flow increases >30-fold in human and sheep during gestation to ensure the optimal growth and development of the fetus. Hemodynamic changes in the uterine circulation are mainly achieved through the remodeling of uterine vasculature,1 enhanced vasodilator response,2–5 blunted vasoconstrictor response,6–8 and reduced pressure-dependent myogenic reactivity.9–12 Hypoxia during gestation constitutes a major insult to maternal cardiovascular homeostasis, and the adaptive changes in uterine circulation are complicated by high-altitude chronic hypoxia that inhibited the pregnancy-induced reduction of myogenic tone of uterine arteries.13 Consequently, chronic hypoxia attenuated pregnancy-induced increase in uterine blood flow.14,15 Hypoxia-induced aberration of uterine circulation in pregnancy is believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of many pregnancy complications. Reduced uterine blood flow and inadequate perfusion of the placenta have been attributed to the increased incidence of preeclampsia and fetal intrauterine growth restriction.15–20

The large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel is abundantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. The BKCa channel is a tetramer formed by pore-forming α subunits along with accessory β1 subunits; and the channel complex is activated by membrane depolarization and/or an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Opening of the channel allows K+ efflux across the plasma membrane leading to hyperpolarization, whereas closure of the channel causes depolarization. Therefore, the activity of the BKCa channel is critical in determining the membrane potential of vascular smooth muscle cells and, hence, vascular tone.21 Participation of the BKCa channel in the regulation of vascular tone is evidenced by the development of myogenic contraction and elevated blood pressure attributed to pharmacological blockade of the channel and targeted deletion of BKCa channel genes.22–25 Previous studies have suggested that the BKCa channel is involved in the regulation of uterine circulation and the increase in uterine blood flow during pregnancy.26–28 We have demonstrated recently that blockade of the BKCa channel with tetraethylammonium abolishes the pregnancy-induced attenuation of myogenic tone of uterine arteries and that upregulated expression of the BKCa channel β1 subunit and subsequently heightened BKCa channel activity are responsible for the attenuated myogenic tone of the uterine artery during pregnancy.12 Thus, pregnancy-mediated upregulation of BKCa channel function plays a key role in the adaptation of uterine vascular hemodynamics during pregnancy.

The BKCa channel in vascular smooth muscle cells is a major effector in response to hypoxia. Vascular responses to both acute and chronic hypoxia involve altered BKCa channel activity and/or expression in various vascular beds.29–31 Because of the crucial role of the BKCa channel in pregnancy-mediated adaptation of uterine arterial myogenic tone and the negative impacts on both uterine blood flow and myogenic tone exerted by chronic hypoxia and pharmacological blockade of the BKCa channel, we hypothesized that chronic hypoxia during gestation adversely affects the uterine circulation via downregulating BKCa channel function in uterine arterial smooth muscle cells. Given that sex steroid hormones play a pivotal role in upregulating the β1 subunit and increasing the BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries during pregnancy,12 we further tested the hypothesis that chronic hypoxia inhibits steroid hormone-mediated upregulation of the β1 subunit and BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Preparation and Treatment

Uterine arteries were harvested from nonpregnant and near-term pregnant (≈140 days’ gestation) sheep maintained at sea level (≈300 m) or exposed to high-altitude (3801 m) hypoxia for 110 days.32 Animals were anesthetized with thiamylal (10 mg/kg, IV) followed by inhalation of 1.5% to 2.0% halothane. An incision was made in the abdomen and the uterus exposed. The resistance-sized uterine arteries (≈150 µm in diameter) were isolated and removed without stretching and placed into a modified Krebs solution. For hormonal treatment, arteries from nonpregnant sheep were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal-stripped FBS for 48 hours at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator with 20.5% O2 for tissues from normoxic animals and 10.5% O2 for tissues from hypoxic animals, in the absence or presence of 17β-estradiol (0.3 nmol/L; Sigma) and progesterone (100.0 nmol/L; Sigma), as reported previously.12,32,33 The concentrations of 17β-estradiol and progesterone chosen are physiologically relevant, as observed in ovine pregnancy,34 which have been shown to exhibit direct genomic effects on BKCa channel function and pressure-dependent myogenic tone in the uterine artery.12,32,33 All of the procedures and protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee and followed the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Measurement of BKCa Channel Current

Arterial smooth muscle cells were enzymatically dissociated from resistance-sized uterine arteries, and whole-cell K+ currents were recorded using an EPC 10 patch-clamp amplifier with Patchmaster software (HEKA, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) at room temperature, as described previously.12 Briefly, cell suspension drops were placed in a recording chamber, and adherent cells were continuously superfused with HEPES-buffered physiological salt solution containing (in mmol/L): 140.0 NaCl, 5.0 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10.0 HEPES, and 10.0 glucose (pH 7.4). Only relaxed and spindle-shaped myocytes were used for recording. Micropipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass and had resistances of 2 to 5 mol/LΩ when filled with the pipette solution containing (in mmol/L) 140.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 5.0 Na2ATP, 5.0 EGTA, and 10.0 HEPES (pH 7.2). CaCl2 was added to bring free Ca2+ concentrations to 100.0 nmol/L, as determined using WinMAXC software (Chris Patton, Stanford University). Cells were held at −50 mV, and whole-cell K+ currents were evoked by voltage steps from −60 mV to +80 mV by stepwise 10-mV depolarizing pulses (350-ms duration, 10-s intervals). The K+ currents were normalized to cell capacitance and were expressed as picoampere per picofarad (pA/pF). The BKCa channel current was determined as the difference between the whole-cell K+ current in the absence of iberoitoxin (IBTX; Sigma) or tetraethylammonium (TEA; Sigma) and that in the presence of IBTX or TEA.12

Measurement of Myogenic Tone

Pressure-dependent myogenic tone of resistance-sized uterine arteries was measured as described previously.12,32,33 Briefly, the arterial segments were mounted and pressurized in an organ chamber (Living Systems Instruments, Burlington, VT). The intraluminal pressure was controlled by a servo-system to set transmural pressures, and arterial diameter was recorded using the SoftEdge Acquisition Subsystem (IonOptix LLC, Milton, MA). After the equilibration period, the intraluminal pressure was increased in a stepwise manner from 10 to 100 mmHg in 10-mmHg increments, and each pressure was maintained for 5 minutes to allow vessel diameter to stabilize before the measurement. The passive pressure-diameter relationship was conducted in Ca2+-free PSS containing 3.0 mmol/L of EGTA to determine the maximum passive diameter. The following formula was used to calculate the percentage of myogenic tone at each pressure step: %myogenic tone = (D1 − D2)/D1 × 100, where D1 is the passive diameter in Ca2+-free PSS (0 Ca2+ with 3.0 mmol/L of EGTA), and D2 is the active diameter with normal PSS in the presence of extracellular Ca2+.

Western Immunoblotting

Protein abundance of the BKCa channel α subunit and β1 subunit was measured in freshly isolated uterine arteries and in arteries after ex vivo hormonal treatment, as described previously.12 Briefly, tissues were homogenized in a lysis buffer followed by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10000g, and the supernatants were collected. Samples with equal proteins were loaded onto 7.5% polyacrylamide gel with 0.1% SDS and were separated by electrophoresis at 100 V for 2 hours. Proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking nonspecific binding sites by dry milk, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against BKCa channel α and β1 subunits (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After washing, membranes were incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies. Proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and blots were exposed to Hyperfilm. Results were quantified with the Kodak electrophoresis documentation and analysis system and Kodak ID image analysis software. The target protein abundance was normalized to the abundance of β-actin as a protein loading control.

Data Analysis

Results were expressed as mean±SEM obtained from the number of experimental animals given. Differences were evaluated for statistical significance (P<0.05) by ANOVA or t test, where appropriate.

Results

Chronic Hypoxia Inhibits Pregnancy-Induced Upregulation of BKCa Channel Activity in Uterine Arteries

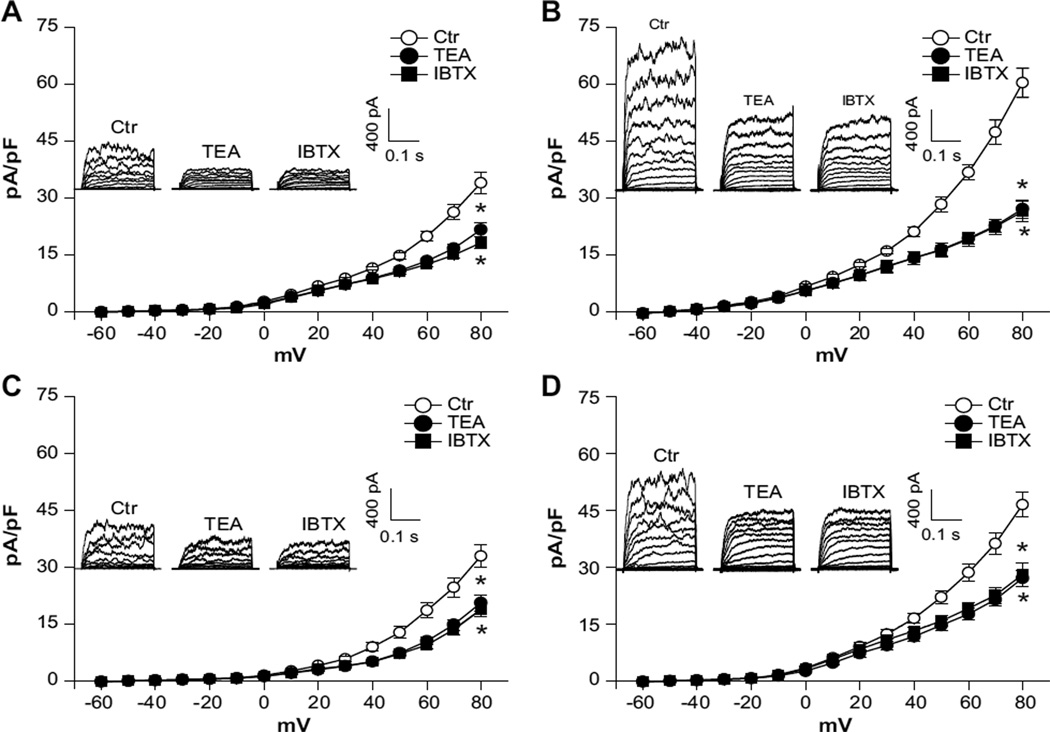

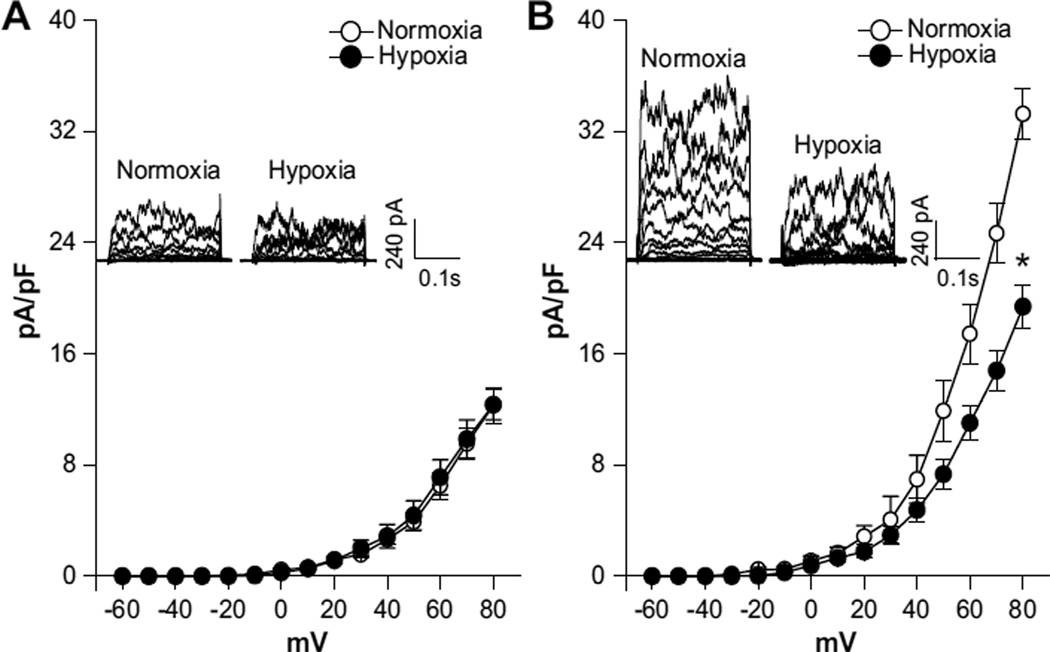

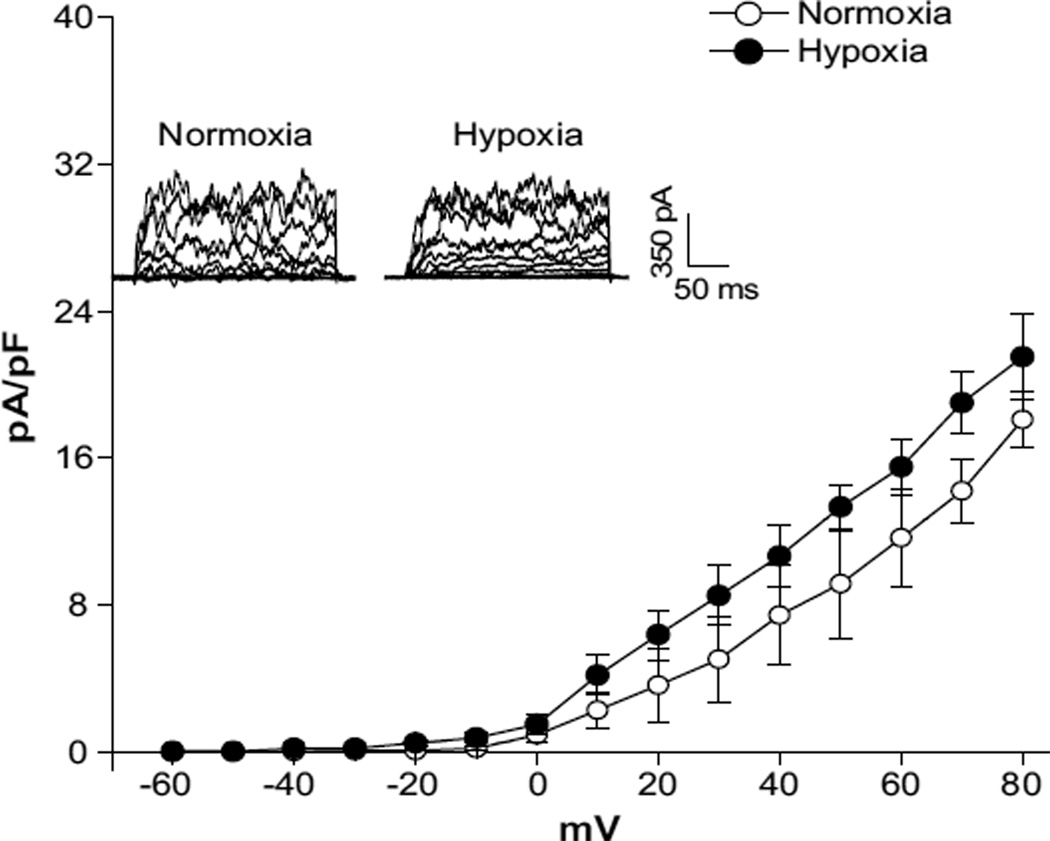

In both normoxic and hypoxic animals, the whole-cell K+ current densities in uterine arterial myocytes in the voltage range of −60 mV to +80 mV were significantly higher in pregnant animals (at +80 mV: normoxia, 60.3±2.7 pA/pF; hypoxia, 46.5±3.3 pA/pF) than in nonpregnant animals (at +80 mV: normoxia, 33.9±2.7 pA/pF; hypoxia, 32.9±3.0 pA/pF; P<0.05; Figure 1). In normoxic animals, pregnancy resulted in an ≈78% increase in the whole-cell K+ current density at +80 mV in uterine arterial myocytes (Figure 1A and 1B). However, this enhancement was significantly blunted by chronic hypoxia, and pregnancy only produced an ≈41% increase in the current density in uterine arterial myocytes in animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia (Figure 1C and 1D). In accordance, chronic hypoxia caused an ≈22% decrease in the whole-cell K+ current density in pregnant uterine arteries (P<0.05) but had no significant effect on the current density in nonpregnant uterine arteries. Whole-cell K+ currents were sensitive to blockade by BKCa channel inhibitors TEA (1.0 mmol/L) or IBTX (100.0 nmol/L). Both TEA and IBTX produced similar inhibition of the K+ currents in uterine arterial myocytes (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 2A, BKCa current densities, determined as the differences of whole-cell K+ currents in the absence or presence of TEA in the voltage range of −60 mV to +80 mV, in nonpregnant uterine arterial myocytes were not altered by chronic hypoxia. In contrast, chronic hypoxia significantly suppressed BKCa current densities in pregnant uterine arterial myocytes and decreased the current density at +80 mV from 33.3±1.8 pA/pF in normoxic animals to 19.4±1.5 pA/pF in hypoxic animals (P<0.05; Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained when the BKCa current density was determined with IBTX (data not shown). Moreover, pregnancy induced ≈1.7-fold and ≈0.6-fold increases in the BKCa current density at +80 mV in the myocytes from normoxic and hypoxic animals, respectively, suggesting that chronic hypoxia during gestation impaired pregnancy-induced upregulation of BKCa channel activity in uterine arterial smooth muscle cells.

Figure 1.

Chronic hypoxia decreases whole-cell K+ currents in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep. Arterial myocytes were freshly isolated from uterine arteries of normoxic and hypoxic sheep. Whole-cell K+ currents were recorded in the absence or presence of tetraethylammonium (TEA; 1.0 mmol/L) or iberoitoxin (IBTX; 100.0 nmol/L). A, Normoxic nonpregnant animals. B, Normoxic pregnant animals. C, Hypoxic nonpregnant animals. D, Hypoxic pregnant animals. Data are mean±SEM of 7 to 10 cells from 5 to 8 animals of each group. *P<0.05 vs control (Ctr). ○, ctr; ●, TEA; ■, IBTX.

Figure 2.

Chronic hypoxia suppresses Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) current density in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep. Arterial myocytes were freshly isolated from uterine arteries of normoxic and hypoxic sheep. BKCa current density was determined in the presence of tetraethylammonium (TEA; 1.0 mmol/L). A, Nonpregnant animals. B, Pregnant animals. Data are mean±SEM of 7 to 10 cells from 5 to 8 animals of each group. *P<0.05 vs normoxia. ○, normoxia; ●, hypoxia.

Chronic Hypoxia Abrogates the Role of the BKCa Channel in Regulating Pressure-Dependent Myogenic Tone of Uterine Arteries

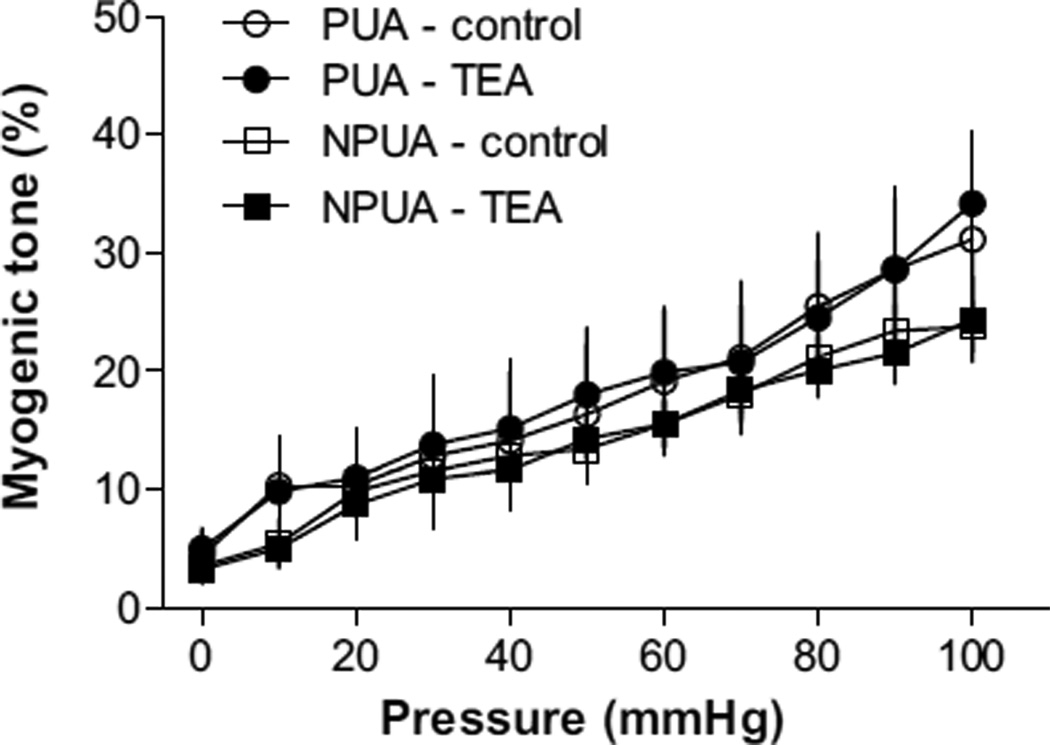

The functional impact of diminished BKCa channel activity in uterine arterial vascular tone was determined by measuring pressure-dependent myogenic responses of resistance-sized uterine arteries in the absence or presence of the BKCa channel inhibitor TEA in hypoxic animals. In response to stepwise increases of intraluminal pressure, myogenic tone developed in both nonpregnant and pregnant uterine arteries (Figure 3). In contrast with the previous finding in normoxic animals in which the pressure-dependent myogenic tone of the uterine artery was significantly diminished in pregnant sheep as compared with that in nonpregnant animals,33 in animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia, the myogenic tone of uterine arteries was significantly increased in pregnant sheep, and there was no significant difference in the myogenic tone of the uterine artery between hypoxic pregnant and nonpregnant animals (Figure 3). We have demonstrated recently that the diminished myogenic tone of pregnant uterine arteries in normoxic sheep is primarily mediated by enhanced BKCa channel activity, and channel blockade by TEA increases myogenic tone and abolishes the difference in myogenic tone of uterine arteries between pregnant and nonpregnant animals.12 In the hypoxic animals, TEA failed to increase uterine arterial myogenic tone (Figure 3), indicating a loss of regulation of uterine vascular tone by the BKCa channel that contributes to the heightened myogenic reactivity observed in pregnant animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia.

Figure 3.

Tetraethylammonium (TEA) has no effects on myogenic tone in uterine arteries of hypoxic animals. Uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant (NPUA) and pregnant (PUA) hypoxic sheep. Pressure-dependent myogenic tone was determined in the absence or presence of TEA (1.0 mmol/L). Data are mean±SEM of tissues from 5 to 6 animals of each group. ○, PUA-control; ●, PUA-TEA; □, NPUA-control; ■, NPUA-TEA.

Chronic Hypoxia Abolishes Steroid Hormone-Induced Upregulation of BKCa Channel Activity in Uterine Arteries

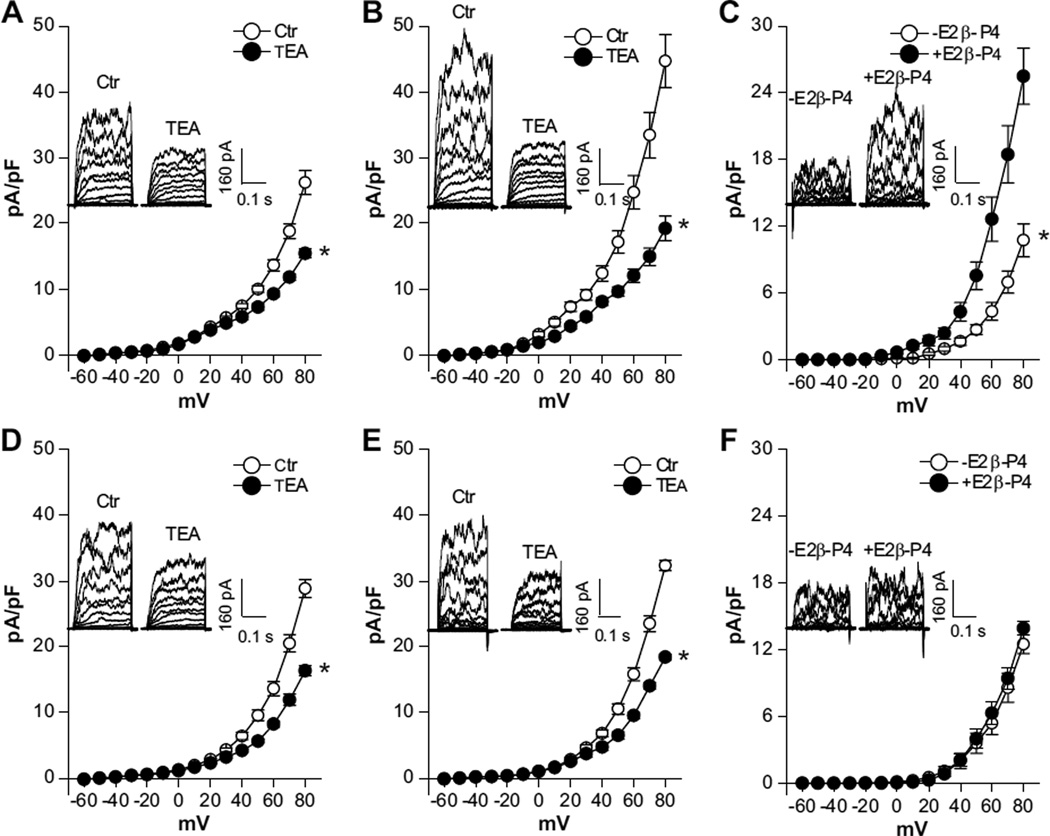

We showed recently that pregnancy-induced upregulation of BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries was largely mediated by the action of 17β-estradiol and progesterone.12 To determine the effects of chronic hypoxia on the steroid hormone-mediated enhancement of BKCa channel activity, uterine arteries isolated from normoxic and hypoxic nonpregnant sheep were treated ex vivo with 17β-estradiol (0.3 nmol/L) and progesterone (100.0 nmol/L) under 20.5% O2 and 10.5% O2, respectively, for 48 hours. The regulation of BKCa channel activity by steroid hormones is illustrated in Figure 4. In a way similar to the effect of pregnancy, the ex vivo hormonal treatment of uterine arteries from normoxic nonpregnant sheep significantly increased whole-cell K+ density at +80 mV in uterine arterial myocytes from 26.2±1.8 pA/pF (Figure 4A) to 44.7±4.0 pA/pF (Figure 4B; P<0.05). Accordingly, the hormonal treatment resulted in significant increases in BKCa current densities (at +80 mV: 25.5±2.5 pA/pF versus 10.7±1.5 pA/pF; P<0.05; Figure 4C). In contrast, the hormonal treatment of uterine arteries from nonpregnant animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia had no significant effect on whole-cell K+ current densities (at +80 mV: 28.9±1.4 pA/pF in control myocytes versus 32.3±0.8 pA/pF in hormone-treated myocytes; P>0.05; Figure 4D and 4E) or BKCa current densities (at +80 mV: 12.5±0.8 pA/pF in control myocytes versus 13.9±0.6 pA/pF in hormone-treated myocytes; P>0.05; Figure 4F) in uterine arterial myocytes.

Figure 4.

Chronic hypoxia inhibits steroid hormone-induced upregulation of Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel activity in uterine arteries. Uterine arteries were isolated from nonpregnant sheep and were treated ex vivo with 17β-estradiol (E2β; 0.3 nmol/L) plus progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L) under 20.5% O2 and 10.5% O2, respectively, for 48 hours. Arterial myocytes were then isolated and whole-cell K+ currents were recorded in the absence or presence of tetraethylammonium (TEA; 1.0 mmol/L). A, Whole-cell K+ currents in myocytes of normoxic animals without hormonal treatment. *P<0.05 vs control (Ctr). B, Whole-cell K+ currents in myocytes of normoxic animals with hormonal treatment. *P<0.05 vs control (Ctr). C, BKCa current density in myocytes of normoxic animals without and with hormonal treatment. *P<0.05, +E2β/P4 vs −E2β/P4. D, Whole-cell K+ currents in myocytes of hypoxic animals without hormonal treatment. *P<0.05 vs control (Ctr). E, Whole-cell K+ currents in myocytes of hypoxic animals with hormonal treatment. *P<0.05 vs control (Ctr). F, BKCa current density in myocytes of hypoxic animals without and with hormonal treatment. Data are mean±SEM of 8 to 10 cells from 6 animals of each group. A, B, D, and E, ○, ctr; ●, TEA. C and F, ○, −E2β-P4;●, +E2β-P4.

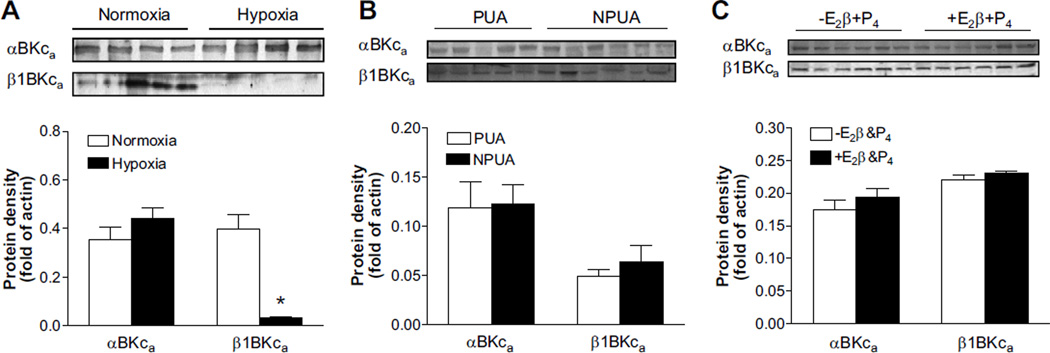

Chronic Hypoxia Inhibits Pregnancy- and Hormone-Induced Upregulation of the BKCa Channel β1 Subunit in Uterine Arteries

The impacts of chronic hypoxia on molecular expression of BKCa channels in uterine arteries were determined with Western immunoblotting analysis. Chronic hypoxia had no significant effects on protein abundance of either BKCa channel α or β subunits in uterine arteries of nonpregnant sheep (data not shown). In pregnant sheep exposed to long-term high altitude hypoxia, uterine arterial BKCa channel α subunit protein abundance was not changed, but BKCa channel β1 subunit protein abundance was significantly decreased (Figure 5A). In contrast to the previous finding in normoxic sheep in which pregnancy upregulated the β1 subunit in uterine arteries,12 pregnancy had no significant effects on either α or β subunit protein abundance in animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia (Figure 5B). Similarly, ex vivo hormonal treatment of uterine arteries from nonpregnant sheep exposed to long-term high-altitude hypoxia failed to modify protein abundance of the BKCa channel α and β1 subunits (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Chronic hypoxia inhibits pregnancy- and steroid hormone-induced upregulation of Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel β1 subunit in uterine arteries. Protein abundance of BKCa channel α (αBKCa) and β1 (α1BKCa) subunits was determined by Western blot analyses. A, Freshly isolated uterine arteries of pregnant sheep in normoxic and hypoxic animals. *P<0.05 vs normoxia. B, Freshly isolated uterine arteries from nonpregnant (NPUA) and pregnant (PUA) sheep of hypoxic animals. C, Uterine arteries from nonpregnant sheep of hypoxic animals were treated ex vivo with 17β-estradiol (E2β; 0.3 nmol/L) plus progesterone (P4; 100.0 nmol/L) under 10.5% O2 for 48 hours. Data are mean±SEM of tissues from 5 to 6 animals of each group. A, □, normoxia; ■, hypoxia. B, □, PUA; ■, NPUA. C, □, −E2β&P4; ■, +E2β&P4.

Chronic Hypoxia Suppresses Protein Kinase C–Mediated Inhibition of BKCa Channel Activity in Uterine Arteries of Pregnant Animals

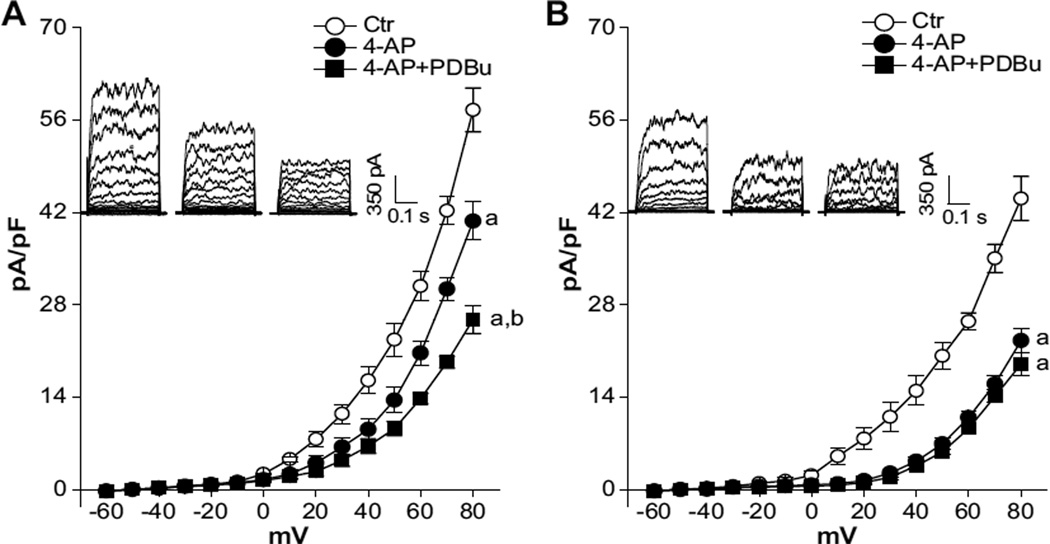

Given that the BKCa channel presents a functional link in pregnancy-mediated downregulation of protein kinase C (PKC) and myogenic tone of uterine arteries,12 the effect of chronic hypoxia on PKC-mediated modulation of BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep was assessed. To determine the effect of PKC on BKCa channel activity, we selectively blocked the K+ current mediated by voltage-gated K+ channels (KV) with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)35 and examined the effect of phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) on the 4-AP–insensitive component of whole-cell K+ currents (ie, BKCa component). As predicted, the application of 4-AP inhibited whole-cell K+ currents in uterine arterial myocytes. However, the resultant KV current densities determined as the differences of whole-cell K+ currents in the absence or presence of 4-AP in the voltage range of −60 mV to +80 mV were not significantly different between normoxic and hypoxic animals (Figure 6). As shown in Figure 7A, PKC activation by PDBu in the presence of 4-AP significantly inhibited the BKCa channel activity and decreased the current density at +80 mV from 40.7±2.9 to 26.8±1.5 pA/pF (P<0.05) in uterine arterial myocytes from normoxic sheep. In pregnant sheep acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia, the BKCa component was significantly decreased from 40.7±2.9 to 22.6±1.8 pA/pF at +80 mV (P<0.05; Figure 7A and 7B). In contrast to the finding in normoxic sheep, PDBu did not reduce BKCa currents in hypoxic animals at +80 mV (22.6±1.8 versus 19.0±1.7 pA/pF; P>0.05; Figure 7B).

Figure 6.

Chronic hypoxia has no effects on voltage-gated K+ (KV) channel activity in uterine arteries. Arterial myocytes were freshly isolated from uterine arteries of pregnant sheep in normoxic and hypoxic animals. Whole-cell K+ currents were recorded in the absence or presence of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 5.0 mmol/L). KV current density was determined as the fraction of the whole-cell K+ currents blocked by 4-AP. Data are mean±SEM of 5 cells from 5 animals of each group. ○, normoxia; ●, hypoxia.

Figure 7.

Chronic hypoxia diminishes protein kinase C (PKC)-mediated modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel in uterine arteries. Arterial myocytes were freshly isolated from uterine arteries of pregnant sheep in normoxic (A) and hypoxic (B) animals. Whole-cell K+ currents were recorded in the absence or presence of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 5.0 mmol/L) and 4-AP plus phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu; 1.0 µmol/L), respectively. Data are mean±SEM of 5 cells from 5 animals of each group. a, P<0.05 vs control (Ctr); b, P<0.05 vs 4-AP. ○, ctr; ●, 4-AP; ■, 4-AP+PDBu.

Discussion

In the present study we present evidence to support the hypothesis that chronic hypoxia increases myogenic tone of uterine arteries of pregnant sheep via inhibiting BKCa channel function in uterine arterial vascular smooth muscle cells. It has been demonstrated previously that decreased myogenic tone in the uterine artery plays a key role in increased uterine blood flow during pregnancy.9–12,33 The attenuated myogenic tone is largely accommodated by increased BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries of pregnant animals.12 However, the normal adaptation of uterine hemodynamics during pregnancy is complicated by exposure to high-altitude chronic hypoxia, manifested by increased myogenic tone of the uterine artery and reduced uterine blood flow.13,15,16,32,36 Chronic hypoxia also targets other vascular beds; and an increased myogenic tone was observed in small pulmonary arteries from chronically hypoxic rats.37,38 BKCa channel opening causes membrane hyperpolarization and opposes myogenic contraction.21 Reduced BKCa channel activity, therefore, provides a mechanism that increases vascular contraction. The present finding that TEA failed to alter myogenic tone of uterine arteries from pregnant animals exposed to chronic hypoxia suggests a loss of the regulatory role of the BKCa channel in myogenic reactivity. Consistent with this finding, the BKCa current density in uterine arteries was decreased by ≈44% in pregnant animals, and the normal pregnancy-induced upregulation of BKCa channel activity was diminished in animals acclimatized to long-term high altitude hypoxia. Overall, these findings suggest that the regulation of uterine arterial myogenic tone by the BKCa channel in pregnant animals is inhibited by chronic hypoxia during gestation.

Our recent study in sheep revealed that the increased BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries during pregnancy was primarily mediated by the actions of sex steroid hormones 17β-estradiol and progesterone.12 Specifically, molecular expression of the BKCa channel β1 subunit and BKCa channel activity were upregulated in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep, which was mimicked by ex vivo steroid hormonal treatment of uterine arteries from nonpregnant animals. In contrast to these findings, the present study demonstrated that chronic hypoxia impeded pregnancy-associated and steroid-induced upregulation of BKCa channel β1 subunit expression and BKCa channel activity in the uterine artery. Accordingly, the abundance of the BKCa channel β1 subunit was significantly decreased in uterine arteries of pregnant animals acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia as compared with normoxic animals. Thus, chronic hypoxia during gestation selectively downregulates the BKCa channel β1 subunit in uterine arteries of pregnant animals. Not surprisingly, chronic hypoxia also selectively downregulates the BKCa channel β1 subunit in other vascular beds, such as pulmonary arteries29 and aortas,30 as well as cultured vascular smooth muscle cells.30 Hence, the BKCa channel in vascular smooth muscle cells constitutes a major effector of decreasing Po2, and chronic hypoxia selectively targets the BKCa channel β1 subunit. In agreement with our finding that the regulation of uterine arterial myogenic tone by the BKCa channel was ablated in pregnant sheep exposed to chronic hypoxia, Navarro-Antolin et al30 also observed the attenuated vasodilator response mediated by the BKCa channel in the aorta from hypoxic rats. These observations support the notion that blunted molecular and functional expressions of the BKCa channel in vascular smooth muscle cells from hypoxic animals contribute to enhanced vascular tone.

The BKCa channel β1 subunit is ubiquitously expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells.23 The association of the β1 subunit with the pore-forming α subunit significantly increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel complex.39,40 In accordance, deletion of the BKCa channel β1 subunit gene dramatically decreased BKCa channel Ca2+ sensitivity in vascular smooth muscle cells.23 Changes in the stoichiometry of α and β1 subunits have been implicated in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions. BKCa channel activity was enhanced because of the upregulation of the β1 subunit in the mesenteric artery after hemorrhagic shock41 and in the uterine artery during pregnancy.12 On the other hand, depressed BKCa channel activity that resulted from the downregulation of the β1 subunit was demonstrated in the cerebral artery of hypertensive animals.42,43 In the present study, we demonstrated that chronic hypoxia during gestation selectively ablated the pregnancy-induced upregulation of the BKCa channel β1 subunit without affecting the α subunit protein abundance in uterine arteries of pregnant animals. The decreased β1:α subunit stoichiometry in uterine arteries of pregnant animals exposed to chronic hypoxia thus impedes BKCa channel activation, leading to membrane depolarization and increased vascular tone. These findings of molecular and electrophysiological impacts of chronic hypoxia are consistent with the results of functional studies showing increased vascular tone of uterine arteries from pregnant sheep acclimatized to long-term high-altitude hypoxia. Thus, the present study provides a novel mechanism of aberrant BKCa channel activity in reduced uterine blood flow caused by chronic hypoxia during gestation. In contrast to the BKCa channel, the KV channel current density in the uterine artery of pregnant sheep was not significantly different between hypoxic and normoxic animals, indicating minimal role of KV channels in the chronic hypoxia-induced alteration of uterine vascular tone. However, this lack of an effect of chronic hypoxia on KV responses in uterine arteries is not ubiquitous to all vascular smooth muscle. Unlike the uterine artery, chronic hypoxia caused a decrease in the activity of the KV channel in pulmonary arteries,44 suggesting the heterogeneity of tissue response to chronic hypoxia.

Our previous study demonstrated that 17β-estradiol alone was sufficient to upregulate the expression of the BKCa channel β1 subunit in the uterine artery.12 Hence, the downregulation of the BKCa channel β1 subunit in uterine arteries of pregnant animals exposed to high-altitude chronic hypoxia could be a result of decreased 17β-estradiol in the maternal circulation. However, this is unlikely, because maternal plasma 17β-estradiol levels in sheep were not altered by chronic hypoxia.32 Estrogen receptor-α is the predominant estrogen receptor in the uterine artery.32 Thus, the genomic effect of the steroid hormone in upregulating the BKCa channel is likely mediated through the interaction between 17β-estradiol and estrogen receptor-α. Hypoxia has profound impacts on gene expression and protein synthesis.45,46 Chronic hypoxia during gestation downregulates estrogen receptor-α expression in uterine arteries.32 Consequently, suppressed BKCa channel β1 subunit expression in uterine arteries could be attributed to reduced expression of estrogen receptor-α. Accordingly, chronic hypoxia suppressed pregnancy- and steroid hormone-mediated attenuation of uterine arterial myogenic tone.32

Consistent with the previous studies showing that BKCa channel activity was inhibited by PKC in vascular smooth muscle cells,47–50 the present study demonstrated that PDBu significantly decreased the 4-AP–insensitive component of whole-cell K+ currents, that is, the BKCa current in uterine arteries of pregnant animals. This finding, combined with our previous results that the activation of PKC by PDBu produced the same increase in pressure-dependent myogenic tone of uterine arteries in pregnant animals as the inhibition of BKCa channel by TEA,12 provides evidence that PKC-mediated inhibition of BKCa channel activity is functionally coupled to myogenic tone of uterine arteries. Given that the PKC activity in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep was enhanced by chronic hypoxia,13 we reasoned that activation of PKC may exert greater inhibition on BKCa channel activity in the uterine arteries of pregnant animals exposed to high-altitude hypoxia. Surprisingly, our data suggest that PKC-mediated inhibition of BKCa activity in uterine arteries of pregnant animals was diminished by chronic hypoxia. Although this may be because of a loss of the regulatory role of PKC on the BKCa channel, the significantly decreased BKCa channel activity in the uterine arteries caused by chronic hypoxia during gestation may also contribute to the diminished effect of PDBu. Similar findings have been reported in pulmonary arteries, showing that chronic hypoxia inhibits the KV channel activity and diminishes the PKC-mediated inhibition of the KV channel.44,51,52 It should be noted, however, that the KV channel activity in uterine arteries does not appear to be modulated by PKC, because PDBu had no effect on TEA-insensitive K+ currents, that is, KV current density in uterine arterial myocytes from both nonpregnant and pregnant animals.12

Perspectives

Chronic hypoxia during gestation has profound adverse effects on the normal adaptation of uteroplacental circulation to pregnancy and increases the incidence of preeclampsia and fetal intrauterine growth restriction.14–17,36,53,54 Studies in a variety of animal models have demonstrated a critical link between reductions in uteroplacental blood flow with prolonged uteroplacental ischemia and a hypertension state that closely resembles preeclampsia in women.55,56 BKCa channels play a key role in regulating the uterine circulation during pregnancy.12,26–28 The present study provides evidence of a novel mechanism of aberrant BKCa channel function in abnormal uteroplacental circulation caused by chronic hypoxia during gestation and, hence, improves our understanding of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Further studies on the regulation of BKCa channel transcription, translation, and trafficking should provide more insights into mechanisms at the molecular level.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Chronic hypoxia during gestation selectively inhibits the BKCa channel activity in uterine arteries.

The inhibition of BKCa channel activity by hypoxia is attributed to the loss of steroid hormone-mediated upregulation of the BKCa channel β1 subunit.

Diminished BKCa channel function accounts for heightened uterine arterial myogenic reactivity.

What Is Relevant?

Heightened uterine arterial myogenic tone leads to reductions in uteroplacental blood flow observed in pregnancy with hypoxia.

Gestational hypoxia and reduced uteroplacental perfusion are major risk factors of preeclampsia.

Dysregulation of the stoichiometric composition of BKCa channels is a common contributing factor in the pathogenesis of hypertension.

Summary

The present study demonstrates a novel mechanism of aberrant BKCa channel function in heightened uterine arterial myogenic tone and impaired uteroplacental circulation seen in pregnancy with hypoxia and thus improves the understanding of pathogenesis of preeclampsia and suggests new insights of therapeutic strategies that may be beneficial for pregnant women with preeclampsia, as well as for the treatment of hypertension in general.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD031226 (to L.Z.), HL089012 (to L.Z.), HL110125 (to L.Z.), and DA025319 (to S.Y.) and by National Science Foundation grant MRI-DBI 0923559 (to S.M.W.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Osol G, Mandala M. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:58–71. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni Y, May V, Braas K, Osol G. Pregnancy augments uteroplacental vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression and vasodilator effects. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H938–H944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson SH, Steinsland OS, Suresh MS, Lee NM. Pregnancy augments nitric oxide-dependent dilator response to acetylcholine in the human uterine artery. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1361–1367. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.5.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangula PR, Zhao H, Supowit S, Wimalawansa S, DiPette D, Yallampalli C. Pregnancy and steroid hormones enhance the vasodilation responses to CGRP in rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H284–H288. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao D, Pearce WJ, Zhang L. Pregnancy enhances endothelium-dependent relaxation of ovine uterine artery: role of NO and intracellular Ca2+ Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H183–H190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner C, Liu KZ, Thompson L, Herrig J, Chestnut D. Effect of pregnancy on endothelium and smooth muscle: their role in reduced adrenergic sensitivity. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1275–H1283. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson SH, Steinsland OS, Johnson RL, Suresh MS, Gifford A, Ehardt JS. Pregnancy-induced alterations of neurogenic constriction and dilation of human uterine artery. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1694–H1701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke CL, Davidge ST. Pregnancy-induced alterations of vascular function in mouse mesenteric and uterine arteries. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1072–1077. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandley RE, Conrad KP, McLaughlin MK. Endothelin and nitric oxide mediate reduced myogenic reactivity of small renal arteries from pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1–R7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veerareddy S, Cooke CL, Baker PN, Davidge ST. Vascular adaptations to pregnancy in mice: effects on myogenic tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2226–H2233. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00593.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao D, Buchholz JN, Zhang L. Pregnancy attenuates uterine artery pressure-dependent vascular tone: role of PKC/ERK pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2337–H2343. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01238.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu XQ, Xiao D, Zhu R, Huang X, Yang S, Wilson S, Zhang L. Pregnancy upregulates large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel activity and attenuates myogenic tone in uterine arteries. Hypertension. 2011;58:1132–1139. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang K, Xiao D, Huang X, Longo LD, Zhang L. Chronic hypoxia increases pressure-dependent myogenic tone of the uterine artery in pregnant sheep: role of ERK/PKC pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1840–H1849. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00090.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamudio S, Palmer SK, Droma T, Stamm E, Coffin C, Moore LG. Effect of altitude on uterine artery blood flow during normal pregnancy. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:7–14. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Julian CG, Galan HL, Wilson MJ, Desilva W, Cioffi-Ragan D, Schwartz J, Moore LG. Lower uterine artery blood flow and higher endothelin relative to nitric oxide metabolite levels are associated with reductions in birth weight at high altitude. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R906–R915. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00164.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zamudio S, Palmer SK, Dahms TE, Berman JC, Young DA, Moore LG. Alterations in uteroplacental blood flow precede hypertension in preeclampsia at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:15–22. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer SK, Moore LG, Young D, Cregger B, Berman JC, Zamudio S. Altered blood pressure course during normal pregnancy and increased preeclampsia at high altitude (3100 meters) in Colorado. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70611-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khalil RA, Granger JP. Vascular mechanisms of increased arterial pressure in preeclampsia: lessons from animal models. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R29–R45. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00762.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George EM, Granger JP. Mechanisms and potential therapies for preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore LG, Charles SM, Julian CG. Humans at high altitude: hypoxia and fetal growth. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;178:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill MA, Yang Y, Ella SR, Davis MJ, Braun AP. Large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa) and arteriolar myogenic signaling. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2033–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial tone by activation of calcium-dependent potassium channels. Science. 1992;256:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1373909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pluger S, Faulhaber J, Furstenau M, Lohn M, Waldschutz R, Gollasch M, Haller H, Luft FC, Ehmke H, Pongs O. Mice with disrupted BK channel β1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca2+ spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ Res. 2000;87:E53–E60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sausbier M, Arntz C, Bucurenciu I, Zhao H, Zhou XB, Sausbier U, Feil S, Kamm S, Essin K, Sailer CA, Abdullah U, Krippeit-Drews P, Feil R, Hofmann F, Knaus HG, Kenyon C, Shipston MJ, Storm JF, Neuhuber W, Korth M, Schubert R, Gollasch M, Ruth P. Elevated blood pressure linked to primary hyperaldosteronism and impaired vasodilation in BK channel-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156448.74296.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfeld CR, Cornfield DN, Roy T. Ca2+-activated K+ channels modulate basal and E2β-induced rises in uterine blood flow in ovine pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H422–H431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld CR, Roy T, DeSpain K, Cox BE. Large-conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ channels regulate basal uteroplacental blood flow in ovine pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenfeld CR, Liu XT, DeSpain K. Pregnancy modifies the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel and cGMP-dependent signaling pathway in uterine vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1878–H1887. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01185.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnet S, Savineau JP, Barillot W, Dubuis E, Vandier C, Bonnet P. Role of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels in the remission phase of pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:326–336. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro-Antolin J, Levitsky KL, Calderon E, Ordonez A, Lopez-Barneo J. Decreased expression of maxi-K+ channel β1-subunit and altered vasoregulation in hypoxia. Circulation. 2005;112:1309–1315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebremedhin D, Yamaura K, Harder DR. Role of 20-HETE in the hypoxia-induced activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel currents in rat cerebral arterial muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H107–H120. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01416.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang K, Xiao D, Huang X, Xue Z, Yang S, Longo LD, Zhang L. Chronic hypoxia inhibits sex steroid hormone-mediated attenuation of ovine uterine arterial myogenic tone in pregnancy. Hypertension. 2010;56:750–757. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao D, Huang X, Yang S, Zhang L. Direct chronic effect of steroid hormones in attenuating uterine arterial myogenic tone: role of protein kinase c/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Hypertension. 2009;54:352–358. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catchpole HR. Hormonal mechanisms in pregnancy and parturition. In: Cole HH, Cupps PT, editors. Reproduction in Domestic Animals. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White MM, Zhang L. Effects of chronic hypoxia on maternal vasodilation and vascular reactivity in guinea pig and ovine pregnancy. High Alt Med Biol. 2003;4:157–169. doi: 10.1089/152702903322022776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broughton BR, Walker BR, Resta TC. Chronic hypoxia induces Rho kinase-dependent myogenic tone in small pulmonary arteries. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L797–L806. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang XR, Lin AH, Hughes JM, Flavahan NA, Cao YN, Liedtke W, Sham JS. Upregulation of osmo-mechanosensitive TRPV4 channel facilitates chronic hypoxia induced myogenic tone and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;302:L555–L568. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00005.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimigean CM, Magleby KL. The βsubunit increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of large conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels by retaining the gating in the bursting states. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:425–440. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cox DH, Aldrich RW. Role of the β1 subunit in large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel gating energetics: mechanisms of enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:411–432. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao G, Zhao Y, Pan B, Liu J, Huang X, Zhang X, Cao C, Hou N, Wu C, Zhao KS, Cheng H. Hypersensitivity of BKCa to Ca2+ sparks underlies hyporeactivity of arterial smooth muscle in shock. Circ Res. 2007;101:493–502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amberg GC, Santana LF. Downregulation of the BK channel β1 subunit in genetic hypertension. Circ Res. 2003;93:965–971. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100068.43006.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amberg GC, Bonev AD, Rossow CF, Nelson MT, Santana LF. Modulation of the molecular composition of large conductance, Ca2+ activated K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle during hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:717–724. doi: 10.1172/JCI18684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Platoshyn O, Yu Y, Golovina VA, McDaniel SS, Krick S, Li L, Wang JY, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Chronic hypoxia decreases KV channel expression and function in pulmonary artery myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L801–L812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koritzinsky M, Magagnin MG, van den BT, Seigneuric R, Savelkouls K, Dostie J, Pyronnet S, Kaufman RJ, Weppler SA, Voncken JW, Lambin P, Koumenis C, Sonenberg N, Wouters BG. Gene expression during acute and prolonged hypoxia is regulated by distinct mechanisms of translational control. EMBO J. 2006;25:1114–1125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simon MC, Liu L, Barnhart BC, Young RM. Hypoxia-induced signaling in the cardiovascular system. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:51–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonev AD, Jaggar JH, Rubart M, Nelson MT. Activators of protein kinase C decrease Ca2+ spark frequency in smooth muscle cells from cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C2090–C2095. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schubert R, Noack T, Serebryakov VN. Protein kinase C reduces the KCa current of rat tail artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C648–C658. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.3.C648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taguchi K, Kaneko K, Kubo T. Protein kinase C modulates Ca2+-activated K+ channels in cultured rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:1450–1454. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barman SA, Zhu S, White RE. Protein kinase C inhibits BKCa channel activity in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L149–L155. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00207.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia alters effects of endothelin and angiotensin on K+ currents in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L431–L439. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang YC, Ni W, Zhang ZK, Xu YJ. The effect of protein kinase C on voltage-gated potassium channel in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from rats exposed to chronic hypoxia. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yip R. Altitude and birth weight. J Pediatr. 1987;111:869–876. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keyes LE, Armaza JF, Niermeyer S, Vargas E, Young DA, Moore LG. Intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and intrauterine mortality at high altitude in Bolivia. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:20–25. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000069846.64389.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alexander BT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA, Granger JP. Preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia with cardiovascular-renal dysfunction. News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:282–286. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sholook MM, Gilbert JS, Sedeek MH, Huang M, Hester RL, Granger JP. Systemic hemodynamic and regional blood flow changes in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion pressure in pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2080–H2084. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00667.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]