Abstract

Congenital malignant melanoma (CMM) is a rare condition that is defined as malignant melanoma recognized at birth. CMM may develop in utero in one of three ways: (1) transmission by metastasis through the placenta from a mother with melanoma; (2) primary melanoma arising within a giant congenital melanocytic naevus (GCMN); (3) primary de novo cutaneous CMM arising in utero. CMM can be confused clinically and histologically with benign proliferative melanocytic lesions such as giant congenital nevi. We describe the case of a patient presenting a GCMN with proliferative nodules, clinically and dermoscopically resembling a CMM, demonstrating the importance of caution in making a diagnosis of MM and highlighting the possibility that benign lesions as GCMN can mimic a malignant melanoma in this age group.

1. Case Report

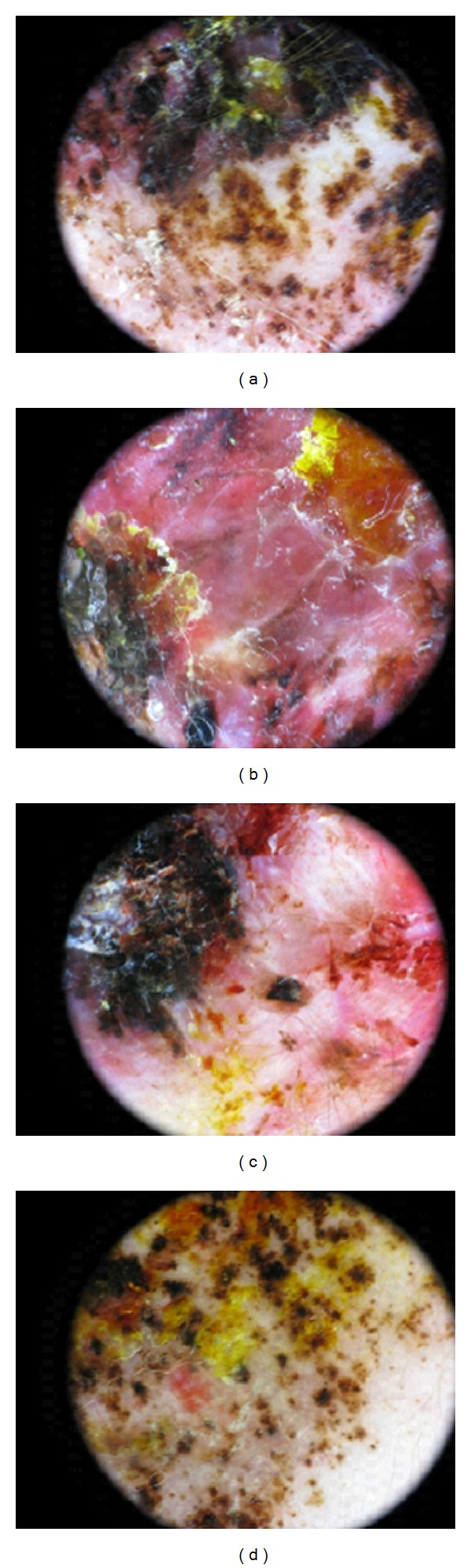

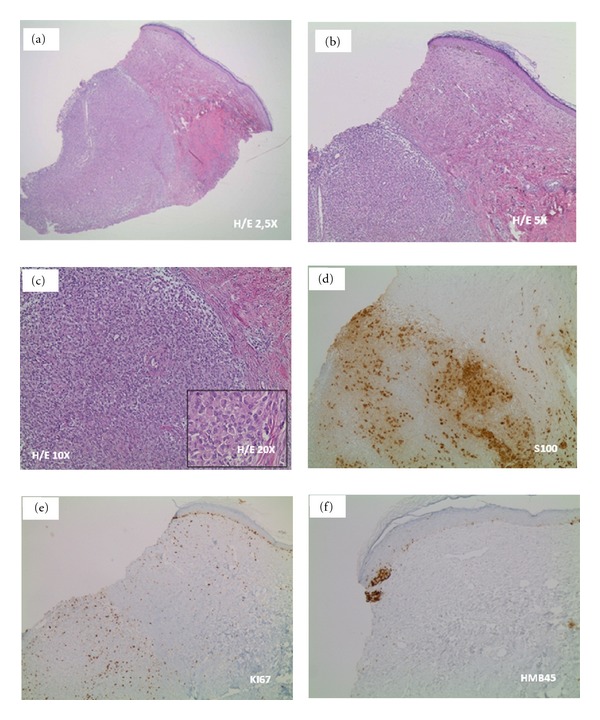

A 7-day-old Italian male child showed at birth a dark, irregular, and raised skin lesion measuring 8 × 11 cm located on the back (Figure 1). He was born full-term by cesarean delivery. The birth weight was 3200 g. He appeared otherwise healthy with no evidence of lymphadenopathy or organomegaly, with an Apgar score of 10. The mother was 30, and she was healthy and received no pharmacological therapies during the pregnancy. There were no maternal suspicious lesions. One month before the delivery, a presumable angiomatous lesion was diagnosed by prenatal ecography. No history of melanoma was known in the family. There were two brothers, without any disease. At the age of 7 days, he was seen at the Department of Dermatology of Federico II of Naples because, according to clinical features of the lesion, there was a very strong suspect of melanoma. A careful dermoscopic examination was performed, which revealed irregular pigmentation, atypical pigment network, irregular dots and globules, irregular streaks, and a wide blue-whitish veil (Figure 2). On the seventh and fourteenth days of life, 4 biopsy specimens of the flat and the raised areas were taken. The specimens were fixed in formalin and sent for histologic analysis. All specimens demonstrated similar histologic features. There was (Figures 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c)) a dermic component characterized by a solid growth pattern with deep melanocytic nodules showing a high hypercellularity with no significant atypia. The melanocytes were densely packed and uniform in nature exhibiting a small nucleus, sometimes with fine nucleoli. Nuclear pleomorphism was not seen. The immunohistochemical stains showed a strong positivity for S-100 protein (Figure 3(d)) and ki67 (Figure 3(e)), while the HMB-45 (human black melanoma 45) staining was negative (Figure 3(f)). A diagnosis of a giant congenital nevus with proliferative dermic nodules was made. There was no histologic evidence of melanoma. A magnetic resonance imaging was performed in order to exclude the presence of brain and spine lesions that can be associated with congenital melanocytic nevus. No leptomeningeal pigmentations or nevi were found in brain and spine. The patient underwent a three-time plastic surgery operation in April, June, and September 2010 that resulted in a complete excision of the lesion (Figure 4). No skin-grafting or cutaneous expander was needed. During a follow-up period of 2 years, this child remained well, with no evidence of malignancy.

Figure 1.

Clinical appearance of a dark, irregular, and raised skin lesion measuring 8 × 11 cm located on the back.

Figure 2.

Dermoscopic features. An irregular pigmentation (a–d), atypical pigment network (a–d), irregular dots and globules (a–d), irregular streaks (a–c), and a wide blue-whitish veil (a–c) are clearly visible.

Figure 3.

Histopathologic features. We can see (a–c) a dermic component characterized by a solid growth pattern with deep nodules showing a high hypercellularity with no significant atypia. These melanocytes are densely packed and uniform in nature exhibiting a small nucleus; some cells have fine nucleoli. Nuclear pleomorphism is not seen. Immunohistochemical stains. It is visible a strong positivity for S-100 protein (d) and ki67 (e) but a negativity for the HMB-45 (human black melanoma 45) (f). Abbreviations. H/E: hematoxylin and eosin.

Figure 4.

Clinical appearance of the patient after a three-time plastic surgery operation. No skin-grafting or cutaneous expander was needed.

2. Discussion and Review

Congenital melanocytic nevi are present at birth in 1% to 2% of newborns [20], and GCMN, defined as greater than 20 cm in diameter, has a 2% to 42% risk of malignant transformation, with a 6% to 14% lifetime risk of developing melanoma [20, 21].

Discrete dermal nodular proliferations commonly referred to as “proliferative nodules” [22], “atypical dermal nodules” [23], “atypical epithelioid tumors in congenital nevi” [24], or “proliferative dermal lesions” [25] can be identified in congenital nevi.

Both clinical management and histopathologic interpretation of atypical proliferations in congenital melanocytic nevi pose significant challenges to dermatologists and pathologists [20].

The true incidence of CMM is difficult to determine due to small number of reported cases and problems associated with diagnosis, and it is likely that some of the cases described as “congenital melanoma” may have been undiagnosed GCMN.

CMM is extremely rare. From our review of the available literature, twenty cases of CMM have been reported in the English medical literature since 1925 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Review of neonatal malignant melanoma.

| Case | Authors | Aetiology | Age at diagnosis | Sex | Location of Lesion | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coe [1], 1925 | de novo | Present at birth, diagnosed 8 wk | F | Head | D 10 mo |

| 2 | Sweet and Connerty [2], 1941 | de novo | Present at birth, diagnosed 7 d | M | Buttocks | D 17 d |

| 3 | Stromberg [3], 1979 | de novo | Present at birth, diagnosed 5 mo | No data | Mastoid process | A 18 y |

| 4 | Hayes and Green [4], 1984 | de novo | At birth | M | Disseminated tumor | A 5 y 10 mo |

| 5 | Prose et al. [5], 1987 | de novo | 6 wk | F | Abdomen | A 1 y |

| 6 | Song et al. [6], 1990 | de novo | At birth | M | Occiput | D 2 h |

| 7 | Asai et al. [7], 2004 | de novo | 2 mo | M | Right thumb | A 3 y |

| 8 | Oldhoff and Koudstaal [8], 1968 | GCMN | At birth | M | Right thigh | A 10 y |

| 9 | Stronmberg [3], 1979 | GCMN | At birth | M | Temple | A 6 mo |

| 10 | Campbell et al. [9], 1987 | GCMN | In utero | M | Mass over spine | D 17 min |

| 11 | Naraysingh and Busby [10], 1986 | GCMN | At birth | M | Extensive over back containing tumor nodules; multiple satellite lesions | D 6 wk |

| 12 | Mancianti et al. [11], 1990 | GCMN | 8 wk | No data | Right thigh | A 41 mo |

| 13 | Mancianti et al. [11], 1990 | GCMN | 3 wk | No data | Bathing-trunk nevus with nodules | A 18 mo |

| 14 | Baader et al. [12], 1992 | GCMN | At birth | F | Thoracolumbar and gluteal | A 4 mo |

| 15 | Ishii et al. [13], 1991 | GCMN | Present at birth, diagnosed 40 d | M | Left thigh | D 18 mo |

| 16 | Koyama et al. [14], 1996 | GCMN | At birth | F | Scalp with nodules | No data |

| 17 | Weber et al. [15] 1930, Holland [16], 1949 |

Transplacental | 8 mo | M | Generalized subcutaneous nodules | D 10 mo |

| 18 | Campbell et al. [9], 1987 | Transplacental | 5 mo | No data | Left upper quadrant | D |

| 19 | Dargeon et al. [17], 1950 | Transplacental | 9 mo | M | Preauricular | D 11 mo |

| 20 | Brodsky et al. [18], 1965 | Transplacental | 11 d | M | Cord blood showed malignant cells; multiple lesions on chest wall | D 7 wk |

Abbreviations. GCMN: giant congenital melanocytic nevus; A: alive; D: dead; min: minutes; h: hours; d: days; wk: weeks; mo: months; y: years.

Of the 20 children, 12 were males and 4 females (in 4 cases the sex was not reported). Four of the cases were transplacental metastatic melanomas, 9 GCMN-associated melanoma, and 7 de novo melanoma.

Weber et al. in 1930 [15] and Holland in 1949 [16] reported the first CMM arising from maternal malignant melanoma via placental metastasis. Fetal metastasis is extremely rare, and it has been reported that there is about 25% risk of melanoma with placental metastasis spreading from mother to fetus [26–28]. Of course, in such cases the diagnosis is relatively easy.

Nine neonatal melanomas developed within a GCMN or preexisting nevus; there was evidence of metastasis or local spread in 4 of these patients, 3 of whom subsequently died [29].

The other seven cases arose on apparently normal skin, and 3 of these ended in demise of the patient [29].

GCMN is a great mimicker of malignant melanoma; clinical indicators such as changes in colour, size, shape, rapid growth rate, nodularity, and even ulceration may occur in this benign lesion. Moreover, melanoma-specific dermoscopic criteria may also be present (Table 2).

Table 2.

Seven melanoma-specific dermoscopic criteria [19]. As our case reports, a GCMN may show these features.

| Criterion | Definition | Histopathologic correlates |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Atypical pigment network | Black, brown, or gray network with irregular meshes and thick lines | Irregular and broadened rete ridges |

| (2) Blue-whitish veil | Irregular, confluent, gray-blue to whitish-blue diffuse pigmentation | Acanthotic epidermis with focal hypergranulosis above sheets of heavily pigmented melanocytes in the dermis |

| (3) Atypical vascular pattern | Linear-irregular or dotted vessels not clearly combined with regression structures | Neovascularization |

| (4) Irregular streaks | Irregular, more or less confluent, linear structures not clearly combined with pigment network lines | Confluent junctional nests of melanocytes |

| (5) Irregular pigmentation | Black, brown, and/or gray pigmented areas with irregular shape and/or distribution | Hyperpigmentation throughout the epidermis and/or upper dermis |

| (6) Irregular dots/globules | Black, brown, and/or gray round to oval, variously sized structures irregularly distributed within the lesion | Pigment aggregates within stratum corneum, epidermis, dermoepidermal junction, or papillary dermis |

| (7) Regression structures | White areas (white scarlike areas) and blue areas (gray-blue areas, peppering, multiple blue-gray dots) may be associated, thus featuring so-called blue-whitish areas virtually indistinguishable from blue-whitish veil | Thickened papillary dermis with fibrosis and/or variable amounts of melanophages |

Histologic features recognized as evidence of malignancy like mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and pagetoid melanocytic proliferation may also be present in a GCMN [29]. Malignant change, however, is exceptional in neonates.

Previous reports have recognized benign proliferative nodules within GCMNs that behave in a nonaggressive manner [11, 30–32]. Despite their clinically and dermoscopically alarming appearance, in time, these nodules may reduce in size, become softer, and even regress completely, and the histologic features become less worrisome [1, 17, 32].

Based on the excellent prognosis of many reported cases, we believe that some previously reported cases of CMM were not malignant lesions.

We believe that our case represents benign large dermal nodules within GCMN that clinically and dermoscopically resembled a malignant melanoma.

Dermoscopy is a very useful technique for the analysis of pigmented lesions; it represents a link between clinical and histological views, affording an earlier diagnosis of skin melanoma.

It also helps in the diagnosis of many other pigmented skin lesions that can mimic melanoma, such as seborrheic keratosis, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, haemangioma, blue naevus, atypical naevus, and benign naevus.

Cutaneous melanoma can show a multiplicity of characteristics like dermoscopic variation of colours and structures and asymmetry. Dermoscopy facilitates diagnostic suspicion, and can predict the depth of the tumor; for example, melanoma in situ and melanoma with dermal invasion exhibit visible differences on close examination. Obviously, its findings have to be confirmed by histopathologic examination [33].

Based on our experience and the literature review, we believe that although a lesion can appear alarming, extreme caution is needed in diagnosing a melanoma in an otherwise healthy neonate.

This paper underlines the importance of a proper diagnosis, for which the histopathological analysis is fundamental; misdiagnosis may lead to anxiety and unnecessary treatment, like chemotherapy and surgical amputations.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Coe HE. Malignant pigmented mole in an infant. Northwest Medicine. 1925;24:181–182. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweet LK, Connerty HV. Congenital melanoma: report of a case in which antenatal metastasis occurred. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1941;62:1029–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stromberg BV. Malignant melanoma in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1979;14(4):465–467. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(79)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes FA, Green AA. Malignant melanoma in childhood: clinical course and response to chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2(11):1229–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.11.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prose NS, Laude TA, Heilman ER, Coren C. Congenital malignant melanoma. Pediatrics. 1987;79(6):967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song KY, Song HG, Chi JG, Graham JG. Congenital malignant melanoma: a case report. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 1990;5(2):91–95. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1990.5.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asai J, Takenaka H, Ikada S, Soga F, Kishimoto S. Congenital malignant melanoma: a case report. British Journal of Dermatology. 2004;151(3):693–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oldhoff J, Koudstaal J. Congenital papillomatous malignant melanoma of the skin. Cancer. 1968;21(6):1193–1197. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196806)21:6<1193::aid-cncr2820210622>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell WA, Storlazzi E, Vintzileos AM. Fetal malignant melanoma: ultrasound presentation and review of the literature. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;70(3):434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naraysingh V, Busby GOD. Congenital malignant melanoma. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1986;21(1):81–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(86)80664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancianti ML, Clark WH, Hayes FA, Herlyn M. Malignant melanoma simulants arising in congenital melanocytic nevi do not show experimental evidence for a malignant phenotype. American Journal of Pathology. 1990;136(4):817–829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baader W, Kropp R, Tapper D. Congenital malignant melanoma. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1992;90(1):53–56. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii N, Ichiyama S, Saito S, Kurosawa T, Nakajima H. Congenital malignant melanoma. British Journal of Dermatology. 1991;124(5):492–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama T, Murakami M, Nishihara O, Masuda T. Congenital melanoma: a case suggesting rhabdomyogenic differentiation. Pediatric Dermatology. 1996;13(5):389–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber FP, Schwarz E, Hellenschmeid R. Spontaneous inoculation of melanotic sarcoma from mother to fetus. British Medical Journal. 1930;1:529–537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3611.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland E. A case of transplacental metastasis of malignant melanoma from mother to fetus. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1949;56:529–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1949.tb07122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dargeon HW, Eversole JW, Del Duca V. Malignant melanoma in an infant. Cancer. 1950;3(article 299) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodsky I, Baren M, Kahn SB, Lewis G, Tellem M. Metastatic malignant melanoma from mother to foetus. Cancer. 1965;18:1048–1054. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196508)18:8<1048::aid-cncr2820180817>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, De Giorgi V, Sammarco E, Delfino M. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions: comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Archives of Dermatology. 1998;134(12):1563–1570. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alper JC, Holmes LB. The incidence and significance of birthmarks on a cohort of 4,641 newborns. Pediatric Dermatology. 1983;1(1):58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1983.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittencourt FV, Marghoob AA, Kopf AW, Koenig KL, Bart RS. Large congenital melanocytic nevi and the risk for development of malignant melanoma and neurocutaneous melanocytosis. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4 I):736–741. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phadke PA, Rakheja D, Le LP, et al. Proliferative nodules arising within congenital melanocytic nevi: a histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analyses of 43 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2011;35(5):656–669. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821375ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collina G, Deen S, Cliff S, Jackson P, Cook MG. Atypical dermal nodules in benign melanocytic naevi. Histopathology. 1997;31(1):97–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5960830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed RJ, Ichinose H, Clark WH, Mihm MC. Common and uncommon melanocytic nevi and borderline melanomas. Seminars in Oncology. 1975;2(2):119–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elder DE, Murphy GF. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Melanocytic Tumors of the Skin. Washington, DC, USA: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman JF, Lowe L, Redman B, et al. Placental metastasis of maternal melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;49(6):1150–1154. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JF, Kent S, Machin GA. Maternal malignant melanoma with placental metastasis: a case report with literature review. Pediatric Pathology. 1989;9(1):35–42. doi: 10.3109/15513818909022330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh RDW, Chu NM. Placental metastasis from primary ocular melanoma: a case report. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;174(5):1654–1655. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leech SN, Bell H, Leonard N, et al. Neonatal giant congenital nevi with proliferative nodules: a clinicopathologic study and literature review of neonatal melanoma. Archives of Dermatology. 2004;140(1):83–88. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelucci D, Natali PG, Amerio PL, Ramenghi M, Musiani P. Rapid perinatal growth mimicking malignant transformation in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus. Human Pathology. 1991;22(3):297–301. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90165-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carroll CB, Ceballos P, Perry AE, Mihm MC, Spencer SK. Severely atypical medium-sized congenital nevus with widespread satellitosis and placental deposits in a neonate: the problem of congenital melanoma and its simulants. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1994;30(5):825–828. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borbujo J, Jara M, Cortes L, De LS. A newborn with nodular ulcerated lesion on a giant congenital nevus. Pediatric Dermatology. 2000;17(4):299–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the internet. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;48(5):679–693. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]