Abstract

How IRBs relate to federal agencies, and the implications of these relationships, have received little, if any, systematic study. I interviewed 46 IRB chairs, directors, administrators, and members, contacting the leadership of 60 U.S. IRBs (every fourth one in the list of the top 240 institutions by NIH funding), interviewing IRB leaders from 34 (response rate=55%). IRBs describe complex direct and indirect relationships with federal agencies that affect IRBs through audits, guidance documents, and other communications, and can generate problems and challenges. Researchers often blame IRBs for frustrations, but IRBs often serve as the “local face” of federal regulations and agencies and are “stuck in the middle.” These data have critical implications for policy, practice, and research.

Keywords: research ethics, health care system, organizational system, sociology, policymaking, regulations

How IRBs relate to federal agencies, and the implications of these relationships, have received little, if any, attention. IRBs result from federal mandates, but empirical research has tended to approach IRBs as isolated entities. Studies of IRBs have tended to focus on logistical issues, e.g., members’ education and socio-demographics, and length of time that transpires before approval (Greene & Geiger, 2006; De Vries, Anderson, & Martinson, 2006; Larson et al., 2004), and discrepancies in IRBs’ decisions in multi-site studies (Greene & Geiger, 2006; McWilliams et al., 2003; Dziak et al., 2005). Yet how IRBs relate to federal agencies over time, and whether and how these interactions and perceptions may affect IRBs, have not been examined.

Some critics have questioned whether the current system is “broken” (Fleischman, 2005). In multi-site studies, IRBs vary widely in reviews of the same protocol (Greene & Geiger, 2006; McWilliams et al., 2003; Dziak et al., 2005). Critics have called for revamping the status quo (Menikoff, 2010). Recently, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) proposing dramatic shifts in regulations governing IRBs (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011; Emanuel & Menikoff, 2011). But whether proposed changes will be instituted, and if so, which, when, to what degrees, in what ways, and with what outcomes and success, remain unclear. Hence, given the possibility of changes, understanding how IRBs view and relate to federal regulations and agencies is of increasing importance.

IRBs have also faced challenges incorporating the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) (Kulynych & Korn, 2003), and have been criticized for spending too much time on forms (Schrag, 2010; Burris, 2008). The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) and the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) have also been criticized for focusing on minor errors in paperwork (Fost & Levine, 2007). But how IRBs themselves view such regulatory challenges, and their own roles and responses, and criticisms that they have then received as a result, have not been examined.

Many laws may need to be vague (Endicott, 2001) and may be illusory (Bellis, 2008). But for the law, courts provide interpretations that are documented and disseminated, and establish precedents. Mechanisms also exist for appeals by separate, independent bodies, with the Supreme Court serving as a final interpreter. But with IRBs, none of these mechanisms exist.

Questions thus arise as to how IRBs operate within the regulatory context that they occupy—how they relate to, and interact with, the federal agencies that oversee them. Systems theory has probed how complex social systems function and develop feedback (von Bertalanffy, 1950), and has been applied to numerous types of organizations, including those in health care (Begun, Zimmerman, & Dooley, 2003; Parsons, 1951). Recent scholarship has probed how other types of organizations work in complex social systems, emphasizing the importance of seeing institutions, generally, not as static, but as engaged in dynamic relationships (Emirbayer, 1997). Silbey (2011), for instance, has explored how managers in an academic medical center work to enforce governmental environmental safety regulations (e.g., concerning radioactive waste).

But whether IRBs similarly operate in such dynamic contexts, and if so, how and with what implications, has not been systematically studied. Most research on IRBs has been based on quantitative surveys (Greene & Geiger, 2006; McWilliams et al., 2003; Dziak et al., 2005), though a handful of qualitative studies has recently been published based on access to IRB members. Lidz et al. (2012) found that community member reviewers spoke less than other member reviewers, and were more likely to discuss confidentiality issues. Among nonreviewers, community members discussed consent more than did other members. Stark (2011) examined how members drew on personal and professional experience and on local precedents, and used and were affected by memos to investigators. Many critical questions thus remain concerning how IRBs in fact operate.

In a recent in-depth semi-structured interview study I conducted of views and approaches toward research integrity (RI) among IRB chairs, directors, administrators, and members (Klitzman, 2011c), issues concerning IRB relationships with federal regulations and agencies frequently arose. The study aimed to understand how IRBs view integrity in research, which these participants defined very broadly (Klitzman, 2011c). Interviewees revealed how they viewed and responded to violations of RI in a wide variety of ways, related to how they perceived and approached conflicts of interest (COIs) (Klitzman, 2011a); central IRBs (Klitzman, 2011b); research in the developing world (Klitzman, 2012); and variations among IRBs (Klitzman, 2011d). Interviewees also wrestled with challenges and dilemmas interpreting and applying federal regulations, and perceiving and interacting with federal agencies; and were affected by federal audits due to violations of RI and other factors. They varied in whether they thought additional guidelines and regulations would be helpful, and if so, what, where, and why. Since this study used qualitative methods, it allowed for further detailed explorations of these domains that emerged, shedding light on these issues. This paper thus explores these key aspects of the broad regulatory contexts in which IRBs operate—e.g., how IRBs view and interact with federal agencies, what challenges they face in doing so, and how they respond to these.

Method

As described elsewhere (Klitzman 2012, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, 2011d), I conducted in-depth telephone interviews of two hours each with 46 chairs, directors, administrators, and members. The Columbia University Department of Psychiatry Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants gave informed consent. Additional methodological details are available as supplementary material online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/jer.2012.7.3.50.

Results

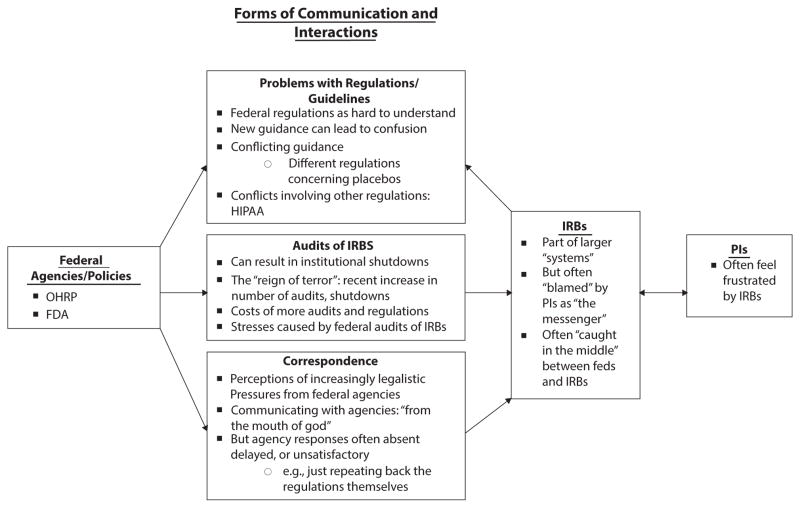

As indicated in Figure 1, and described more fully below, these interviewees highlight how IRBs are embedded in, and profoundly affected by, complex institutional, regulatory, and social systems, which in turn can affect IRBs in several critical ways.

FIG. 1.

Themes Concerning Interactions Between IRBs and Federal Agencies and Regulations.

Complex direct and indirect relationships with federal agencies, particularly OHRP and the FDA, can shape IRBs’ views and decisions. Specifically, the FDA and OHRP can influence IRBs in at least three ways—through audits, guidance documents, and other communications. Each of these types of interactions can pose problems. These relationships are important since they can generate apprehension and stress for IRBs.

Federal Regulations as Hard to Understand

Figuring out how to apply the regulations to many different types of studies can be hard, and federal agencies generally do not provide clarifications as much as IRBs would like, posing inherent problems. In part, “no two studies are exactly the same,” and the complex nature of many protocols does not readily fit the federal guidelines’ pre-established categories, written 35 years ago. IRBs must interpret, apply, and “translate” the regulations, yet lack of federal input, when it is requested, can prompt confusion and discrepancies. As one administrator said:

For prison research, the IRB has to choose one of four categories that fits the study. But these just don’t really fit a lot of research on prisoners these days. We always kind of stretch it a little bit to fit the research into one of these categories. We hold our breath, and say, oh well, it’s sort of A or B. Generally, OHRP wouldn’t disagree. It’s almost a wink and a nod, because both sides know that this stuff stinks to work with. It just doesn’t fit. (IRB18)

Clearly, gray areas emerge. Both sides may realize the clumsiness and “absurdities” of these regulations, but interviewees felt that federal agencies do not readily resolve these difficulties (e.g., by offering helpful clarifications). Current “minimalistic” regulations may thus have costs—not explicitly addressing questions that arise. In other areas, for federal regulations that contain ambiguities, mechanisms exist for clarification. In the law, decisions are documented and published, establishing legal precedents, and the judiciary system and appellate courts regularly work to resolve further disagreements. But for IRB regulations, none of these structures or mechanisms exist. Hence, committees struggle with ambiguities and may seek guidance from federal agencies. Difficulties arise, e.g., concerning blood samples sent from elsewhere, and studied at an institution.

Investigators study rare diseases, and want multiple doctors and researchers to send them samples, as a favor. I’m not going to comment if someone sent them a sample, and that person’s name happens to get put on the published paper. But that’s where I’m having problems. OHRP considers that “engaged in research” because the person is getting recognition. But no, we can’t get IRB approval from that person’s institution. Samples come from all over the world. I would find input useful. (IRB31)

OHRP has issued some clarifications, but many IRBs think these are at times insufficient.

Many IRBs still see the need for further clarification concerning what research requires exempt vs. expedited vs. full-board approval. As one chair said, “We have collaborated with institutions that just don’t exempt any research if it involves interacting with human participants in any way” (IRB33).

As a result, IRBs also face major tensions with PIs, e.g., concerning the applicability of the regulations to social science research. These ambiguities and strains can consume much IRB effort. As one compliance director said:

I spend more time thinking and worrying about specimens, and researchers going into patients’ records in ways that are probably not a risk vs. things that I would like to be spending time on. (IRB31)

Many interviewees noted that PIs frequently complain that IRBs focus on small details. But this problem may arise partly from aspects of these committees’ interactions with federal agencies.

IRBs thought that concrete examples in federal guidance documents could be especially helpful. One federal agency released such a document on expedited review. Such specificity was felt to be beneficial, fulfilling cognitive and pedagogical needs. This interviewee continued:

The regulations are hard. You have to make it more concrete. The National Science and Technology Council—not OHRP—put out a little pamphlet, a guidance document, about expedited review in social and behavioral research. They gave examples of studies where you might want to consider using this expedited procedure. (IRB31)

The fact that the regulations include abstract terms and definitions (e.g., “research” and “minimal risk”) prompts IRBs to struggle to interpret and apply these terms in specific cases—partly because no published precedents exist as they do in the case law.

New Guidance Can Lead to Confusion

Federal agencies also affect IRBs by occasionally issuing new guidelines, documents, and regulations, but these can also generate additional ambiguities and problems. IRBs have to react to such new mandates from OHRP without much negotiation or communication, exacerbating stresses. As a chair said:

Every few months, OHRP and other agencies put out new guidance, and IRBs are jumping around to modify things to fit. There’s not a lot of give and take in terms of: is this reasonable, or helping? It’s just mandated. We’ve spent a lot of time reacting, rather than being proactive…. We don’t have time to be proactive because we keep changing things. That’s not good. (IRB3)

Many interviewees thought agencies can sometimes thus be rigid—doubtlessly partly reflecting constraints that these agencies may themselves confront. But, especially given potential grayness involved in ethical interpretation, flexibility may be helpful.

Given practicalities and complexities, perceived unilateral, rather than bilateral, communication can impede application of such new guidance. This chair continued:

New regs are hard because they need to be implemented and operationalized in the real world, but are not always clear, and there is little opportunity to discuss or negotiate these problems with OHRP. (IRB3)

In many ways, IRBs are thus caught in the middle, and face considerable challenges, having to translate, implement, monitor, and enforce these federal dictates with regard to specific local PIs and protocols. The chair above continued:

A lot of the regs don’t make sense for scientists in the trenches. Policies sound nice, and I’d agree with them, but how do you implement and operationalize them—where you say, “I understand the spirit, but how do we get the spirit from this cut-and-dried, yes-or-no kind of rule?” (IRB3)

IRBs thus wrestle with how best to interpret and carry out these regulations. Interviewees also see distinctions between the policies themselves, and the ways agency officials interpret and implement these policies.

Some interviewees felt that federal focus has increasingly shifted to assessing forms, rather than protecting subjects who may not be better protected now than in the recent past. The chair above added:

New regulations may also not really help the patient. With OHRP and accreditation bodies like AAHRPP, the focus is much more on: do you have the right forms and policies? Not: are patients really better off now than 10 years ago? My sense is no. (IRB3)

Such regulations and guidance may not serve ultimately to protect patients’ interests as best and fully as possible, and may even potentially impede patient protection. This chair sees “more regulatory and bureaucratic stuff, and less focus on the well-being of the patient. AAHRPP is becoming like JCAHO [the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations]” (IRB3).

Additional regulations can also increase IRB expenses in ways that agency and local institutional leaders may not fully recognize, consider, or address. “It’s always costing more and more money to run the IRB,” he added, “because there are more and more levels of regulation” (IRB3).

Conflicting Guidance

Interviewees felt that federal agencies can also disagree with each other (in their guidance), and with other regulations, creating tensions. For instance, the interviewee above, and others, see conflicts concerning:

…whether to exclude women who are of childbearing age and pregnant, but seriously ill and with no other options. NIH keeps saying, “You need to include women, and can’t discriminate against them.” But FDA is pretty clear: most trials exclude women of childbearing potential, unless they are sterilized, and have quadruple birth-control methods—pretty nutty stuff. If women are being excluded, how generalizable is the data? We struggle with that a lot. It would be nice if FDA said that, for certain kinds of studies, it’s silly to exclude women of childbearing potential. If you get a pregnancy test, does someone need to be on birth control for three months to get a one-time injection of a study drug? Why? It would be nice to have it clear: When? (IRB3)

IRBs may thus see agencies as differing on certain issues, partly related to varying approaches in clinical care vs. research. Women can make certain decisions for themselves in clinical but not research settings, posing problems. He added:

If the only way to get a drug is through a trial, are you excluding patients because they happen to be pregnant? In a clinical situation, a patient could say, “Yes, I want to go ahead,” whereas, because it’s research, she can’t. Patients don’t have access to a lot of experimental drugs unless they’re in a trial. It’d be nice to have some clarification and agreement, because these two agencies disagree. (IRB3)

These tensions partly reflect larger differences in standards between clinical vs. research settings, and the relatively higher levels of protection currently in the latter.

Different Regulations Concerning Placebos

IRBs also perceived conflicting views among agencies concerning placebos. When a known effective treatment exists, respondents felt that, compared to OHRP and the Helsinki Declaration, the FDA was more permissive toward studies using placebo to show superiority (Feifel, 2009; Dunlop & Banja, 2009; Laughren, 2001). These positions have been controversial (Howick, 2009), but respondents felt that the FDA may nonetheless at times indirectly sanction placebo use more than OHRP. As a chair said,

One of the better ways to get through the FDA is to have single control data. So, one branch of government sets a bar that requires placebo to get control data. Yet another branch has made it relatively clear that in the U.S., it’s really not ethical to expose people to placebo as a treatment. The solution is to do things elsewhere that wouldn’t be considered ethical in this country. The FDA has no problem accepting those data from abroad. (IRB12)

Some interviewees felt that the FDA does not stipulate placebo use per se but implicitly encourages it—permitting studies that use placebos, when demonstrating a drug’s effectiveness might otherwise be difficult.

Nonetheless, obstacles impede inter-agency reconciliation of such conflict. The fact that many separate federal agencies endorsed 45 CFR 46 can also create obstacles in changing it. “From what I’ve heard, nobody wants to take it on because it’s a lot of work to get so many different agencies to agree to something” (IRB18).

Stresses Caused by Federal Audits of IRBs

Interviewees felt that several years ago, OHRP began to conduct more audits, “shutting down” research and issuing more guidance, but consequently generating stress. Audits may be routine, and not “for cause,” but nonetheless can lead to “shutdowns” of an institution’s IRB(s).

Audits can result from complaints that can vary from justified to frivolous, and be triggered by subjects or researchers, including whistleblowers, or by an IRB itself reporting a problem. A federal audit could be triggered by a single complaint, and cost millions, yet in the end find little, if anything. “The investigator was cleared of the original charges,” a chair said, but “it was a long, multimillion dollar investigation” (IRB15).

Federal audits could be triggered by faculty who are disgruntled and/or have mental health issues. One faculty member sent OHRP a 25-page report, claiming that an international collaborative study in a foreign country had not gotten informed consent. These claims proved untrue, but prompted a large investigation. Ultimately, however, the IRB received more support from its institution.

Informed consent was obtained, but did not necessarily include everything the Common Rule says it should. The accusation was made by a disgruntled former faculty member here who, by other folks’ accounts, has some mental health issues. He was driven to try to “take down” this PI. He wrote a 25-page complaint, and named 10 to 12 studies, and threw in a couple with an American PI—apparently just to make it look like it wasn’t racist. He wrote to the university president and said, “You should build health care clinics for all the poor people there, and if you want I’ll come and run them for you.” Then, he applied for the money himself. With that kind of big, 25-page complaint, OHRP thought well, this person has credibility, so they needed to take it seriously. They asked a lot of questions, and with that many studies, the back-and-forth took a lot of time. OHRP perceived this foreign country’s government to be coercive and dictatorial. Patients were not being herded into a study, but that’s what he accused. OHRP found no evidence that these claims were true, but it took four years! We ended up getting out of it with a clean slate—mostly just with small administrative stuff—you didn’t include this or that in the consent form. But there was no finding of any harm to subjects. (IRB18)

Complaints can thus have little, if any, justification, but get taken seriously and create problems.

One chair reported that her institution was audited by the FDA multiple times in a year. PIs who received the most industry support were particularly audited.

The FDA does about a thousand visits per year nationwide. They tend to pick us because we have a huge amount of industry funding. So, the FDA was here 14 times—very often to see the high-end rollers. The FDA says that lots of industry funding isn’t a criterion for who gets audited, but we know it often is. Most researchers did fine, but a couple did not, because they didn’t have things in the correct order. (IRB11)

This metaphor of “high-end rollers” suggests gamblers/risk takers, lots of cash, and aspects of a game and gaming. This co-chair also distinguishes between the substance vs. form (i.e., “order”) of documentation; and suggests that the latter, not the former, was deficient. Whether her institution was actually in fact audited this many times is unclear, but her impression that that was the case is nevertheless important.

The threat of a follow-up looms over this institution and its IRBs. The FDA has not revisited in the past eight months, but presumably will. “They’ve told us they will be back” (IRB11). Government audits of IRBs can thus generate considerable stress, since whether, when, and how federal agencies will respond can be uncertain. Another chair said,

We had basically a routine audit. There were some findings which we responded to. We never even heard back whether those findings were appropriately addressed or not. Then a few months later, we got the letter that basically we were being shut down. In some ways, maybe, we were an example because there were many other IRBs—pretty high-profile IRBs—going through the same thing at the same time. (IRB6)

These audits can also burden IRBs perhaps more than necessary, partly because these agencies can choose to examine exceedingly small details. As one chair said about the FDA,

They give us anywhere from 24 hours to a week’s notice, and will look at everything—all the documentation, to make sure it’s there, accurate, and complete—that amendments, adverse events, or violations have been noted…that there’s a copy of that EKG…the slightest thing. (IRB11)

But questions arise as to whether this level of detail is appropriate, and helps or hinders overall IRB effectiveness. These interviewee statements may be seen merely as complaints, but reflect these individuals’ views and experiences.

In responding to these agencies, IRBs and PIs face challenges, and may get defensive. Despite the focus on seemingly minor matters, and frustrations with audits, interviewees felt that individuals had to be careful not to respond resentfully. The chair above added:

You have to just listen to what they say. They submit a letter, and you have a right to respond. You have to be careful how your letter is worded. Some FDA inspectors are very easy to work with; others are very strict, following the letter of the law. It can be nerve-wracking…. If the investigator gets defensive and angry, it can ignite a fuse, and can get out of control. (IRB11)

As she suggests, differences can arise in the degree to which particular individual agency personnel follow “the letter” vs. the spirit of the law. Some federal audit citations can seem “ridiculous”—e.g., as one chair described, the number of IRB members voting doesn’t match the number in the room “because someone went to the bathroom” (IRB27).

IRBs see these audits as occurring within the context of a larger system that is itself already difficult to navigate. This larger “system” can be cumbersome, frustrating PIs. As a chair said,

The system is hard to work with…. Not just with the OHRP’s perceived vindictiveness to nail people. It’s not just constraint. It’s trying to work a system that’s difficult and complicated. (IRB25)

He perceives “vindictiveness” of federal agencies—antagonism that can strain IRBs. Yet, he suggests that underlying inherent complexities of research ethics will probably continue.

Ultimately, however, audits may have beneficial effects. A chair whose IRB was audited credited the investigation with prompting necessary reorganization and change.

We basically had only one committee. The quality of our minutes and how we documented our votes was very poor. For greater than minimal risk studies, we were doing our continuing reviews inappropriately—not doing them at the full board level. We completely reengineered our whole review process. We now have four panels, and a full-time member who just does exempt and expedited reviews. (IRB6)

He continued:

I wonder: could the audit have been done better on a more collaborative basis? It took the two-by-four hit between the eyes for the institution to realize they needed to commit the resources, expertise, and energy for doing this right. It probably took the shutdown to get everything in place. (IRB6)

Pressures from Federal Agencies as Increasingly Formal and Legalistic

Many interviewees also felt that over the past 20 years, federal agencies and relationships have become more difficult. Due partly to legal pressure from these agencies, interviewees often thought that IRBs have changed from informal to formal and more legalistic. As a former chair said,

The process is now very different than what was originally intended, because of pressure coming down from OHRP, which, at this point, lawyers heavily staff. Historically, IRBs were to be a committee of colleagues with community and nonscientist members…. The reviews were very collegial…. Now, the scrutiny is very different. I’m not sure if it is fruitful. We get letters back from a lawyer going through consent forms line by line, complaining about some specific phrasings. IRBs are getting drawn into legal process. (IRB7)

With increasing funding from industry, the process has, arguably, become more legalistic, too. Additionally, many other sectors of society have become more legalistic and litigious. As this chair continued, “This is part of a larger regulatory drift in American society in relationships between nongovernmental agencies, government, and the courts” (IRB7).

Lawsuits have increasingly affected many aspects of healthcare, including, recently, IRBs. A lawsuit, even if frivolous, can be stressful and involve IRB members and staff.

A patient was given a device to protect against stroke, but did not meet the inclusion criteria. He was consented on the gurney, outside the operating room, and subsequently had a stroke, and sued. His attorneys interviewed a former IRB member who was the primary reviewer. They questioned the detailed wording in the consent form—why the approved wording differed from the model in the university guidelines. (IRB7)

Such perceived liability can cause pressure and consternation, too. Partly because of these mounting pressures, this interviewee later resigned as chair.

Communicating with Agencies: “From the Mouth of God”

Interviewees often felt that these problems were compounded by the fact that federal agencies at times communicated with local IRBs in limited or incomplete ways. IRBs may request clarifications from OHRP and the FDA concerning gray areas, but feel that the answers are “unhelpful.” Interviewees reported that these agencies would sometimes either not respond, or do so unsatisfactorily, merely reiterating the regulations, without offering clarification. “If they don’t want to say much, they’ll just repeat the regulations in five different ways” (IRB31).

In avoiding issuance of definitive official opinions, federal agencies may thus leave IRBs to wrestle on their own with these deep uncertainties. The lack of federal clarifications leads IRBs to work in an interpretive vacuum that can foster stress and discrepancies. As a chair said, “The Feds often seem to back away from taking a stand. They’ll turn it back to us, and say, ‘It’s up to the IRB.’ They’ll come in and criticize us later” (IRB25). Another chair elaborated,

Many times when you call for advice, they essentially just read back the regulations, and you basically have to make your own decision, which is great, until you have an audit and then you’re told: you didn’t make the right decision. (IRB6)

Chairs thus often feel frustrated and disappointed with these responses, referring IRBs back to the regulations themselves, rather than clarifying or elaborating guidelines. A chair commented,

We want to hear it from the mouth of God, and don’t get that. For the most part, we get vague generalities. That’s not what IRBs need—because all of us have a certain way of doing things. We may think that we handle things optimally, but may be inconsistent with what OHRP wants us to do. (IRB5)

He highlights, too, IRB perceptions that agencies have considerable power and authority.

Moreover, agencies, when they do respond, may not do so in writing, or may say that the clarification does not apply more generally. The chair above continued, about OHRP:

They have not been forthcoming. In fact, it has been very difficult to get any kind of opinion from them, which is very disturbing. If we write to them for an opinion for a very specific situation, they make it very clear that their opinion is relevant to this very specific question, at this specific time, for this particular institution, for this particular subject—they are not providing any general rules or guidance or algorithms. And they rarely will put anything in writing. (IRB5)

More uniformity and clarification may be helpful, but elusive. These interviewees thus raise questions of how often these agencies communicate in writing vs. only verbally; how these decisions about communication are made; and whether differences exist in the content of these two different types of communications, and if so, how and why. Agencies may thus also foster variations among IRBs, though they have not generally been seen as doing so. This reticence may, however, impede optimal IRB functioning. Thus, changes may be needed in not only formal policy structures, but informal relationships as well.

Following an inquiry from an IRB, respondents felt that agency feedback, if it does arrive, may also be much delayed. An administrator said,

Of all the letters we sent, I just got a report back last week saying they have accepted our changes from two years ago! I have not gotten anything back from more recent reports. We’ve never gotten anything back from the FDA. We have very tight time limits for reporting, and 10 working days to make a decision. When it takes them two years to get back to us, it’s a little annoying. Not everything gets back in two years. We have not gotten back things from three years ago! Maybe they were fine with those things, and didn’t feel they needed to correspond back. If we got something back, it would give us validation that we did it right. Somebody said once that if there really were problems, you would hear from them. But how do we know? We get these random letters two years later, so it’s hard to know. (IRB1)

Interviewees felt that OHRP staff frequently won’t even discuss perceived reluctance in responding. As a compliance director said, “The response I get is: it’s in the queue” (IRB31). But without additional or timelier federal guidance, IRBs may be afraid, and thus hesitant to change. “Until something happens at that level, IRBs are going to be scared and very resistant to change” (IRB31). These interactions may thus have critical indirect effects.

OHRP staff may feel restrained, and want to avoid errors, partly reflecting pressures the agency itself may face. But lack of consistent agency guidelines can exacerbate discrepancies among IRBs. An administrator said, “They don’t want to make mistakes or appear like they are being overly prescriptive. But IRBs all need to be doing the same thing” (IRB1).

Interviewees felt that agencies may need to feel “comfortable,” highlighting the roles of subjectivity and emotion in these decisions, even at the federal level. “We made sure that OHRP was feeling comfortable with anything we recommended” (IRB31). Thus, federal officials may themselves face tensions, the amelioration of which may require shifts and improvements not only in formal policy, but in relationships.

Agency staff may wish to assist, but not do so, in part because they and/or their leaders perceive limitations in their mandates, or feel overwhelmed with their current scope of responsibilities. The compliance director above added,

It’s a stalemate down there. They genuinely do want to help. But there’s so much to do, that they do nothing. But if they were just to do a couple of little things, it would help. (IRB31)

OHRP may also face administrative restraints. Some interviewees sympathize with problems that OHRP itself faces because of reduced staff. Though regulations are “clunky,” OHRP staff may feel limited in its ability to interpret or clarify these. As one administrator said,

I was really struck by how incredibly careful they are in the compliance oversight division, not to overstep their authority. They really sweat the determination letters, whether they are going to give feedback on certain issues. They stick very closely to their regulatory authority. (IRB18)

But these agencies and policymakers may not recognize the potential costs of their approach—the fact that it may fuel variations between IRBs. These data also thus highlight questions of how staff in these agencies themselves make decisions.

These responses (or lack thereof) from agencies can also instill fear and apprehension among IRBs. Due to fear, IRBs may shift only in response to direct correspondence from OHRP. (“IRBs are scared, and until OHRP says it’s OK to think about this in these terms, no one is going to change” [IRB31].) OHRP may thus need to take more direct, active, and assertive stances in addressing these issues.

Nonetheless, IRBs may at times avoid approaching these agencies because guidance subsequently received can be binding, not elective. Receiving feedback from agencies can be a double-edged sword. A compliance director added, “Once you go to them, you’ve got to be prepared for their response. You may not like what they say. So, don’t go to them unless you’re prepared” (IRB31).

Yet other IRBs inform OHRP quickly, rather than delaying, partly because they have seen other institutions “nailed” for waiting too long. A few interviewees felt OHRP was reasonable. As one chair said,

We hesitated and debated, but ultimately decided that it was better to report a problem before it became a real problem. We looked back at other institutions that have really gotten nailed because they let things go on too long. It’s better to put the laundry out before it gets too soiled. So, we told OHRP: “We’ve got this problem. Here’s how we are dealing with it already.” They were very reasonable: “Thanks for telling us and fixing it.” (IRB14)

Several interviewees thought that OHRP had improved slightly in responding to questions (as opposed to reports of problems)—suggesting awareness of these tensions. But these interviewees wanted more. They felt, for instance, that agencies could be more open to recommendations for change, e.g., by the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP). A chair reported,

If they would just show some effort to say, “We are listening. Advisory committees are important to us…. We’re doing this, or changing that as a result,” it would make IRBs feel easier. In the last five to 10 years, they are much more approachable. Recently, I e-mailed them a couple of questions. It took them a month and a half to get back to me. But years ago, you wouldn’t get any answer or anything in writing, or they would talk to you on the phone, but put nothing in writing. (IRB31)

Improving the quantity and quality of communication may potentially be very beneficial. One chair suggested, for instance, an “OHRP hotline” to help IRBs with difficulties confronted.

A place where I can call would definitely be helpful—a hotline, not just FAQs. I had to look up and find the wording…. It would have been much easier just to call and say, “Hey, does this qualify for an IRB review?” (IRB29)

Discussion

These interviewees suggest how IRBs occupy particular spaces within larger institutional, regulatory, and social systems, generating several challenges. These data highlight needs to examine IRBs not as isolated entities, but as operating within dynamic contexts. While certain other organizations have been viewed and analyzed from this perspective (Emirbayer, 1997; Begun, Zimmerman, & Dooley, 2003; Parsons, 1951), heretofore, IRBs have generally not been. These data thus underscore the critical importance of viewing IRBs more fully as functioning as part of complex systems in relation to federal agencies and regulations.

While the legitimacy and constitutionality of IRB regulations have been criticized (Heimer & Petty, 2010; Hamburger, 2005), the present data shed light on how exactly IRBs struggle and work within this context, highlighting problems in not only the nature but the implementation of these statutes. Gaps and variations in local institutional implementation of other types of government regulations have been described (Silbey, 2011). Yet such gaps may be less acceptable with regard to IRBs, since patients’ lives may directly and immediately be at stake.

While federal regulations established local IRBs presumably in part to reflect local community values, evidence suggests that such an assumption may not be correct, and that differences between IRBs—even at the same institution—often result instead from differences in personal characteristics of who happens to be IRB members, and at times institutional contexts (Klitzman, 2011d). Nonetheless, agencies may still assume that IRBs are reflecting local community differences, and that government input is thus not greatly needed. However, IRBs often require external guidance. Federal agencies can provide it, and may need to do so more fully and effectively.

Agencies may blame IRBs for over-regulating researchers. But, interviewees here suggest that IRBs see these agencies as themselves strongly affecting, and perhaps sometimes over-regulating, these committees. Both sides may be right, but these perspectives and tensions clearly need additional attention to understand how and when these factors may affect IRBs’ decisions. These interviewees suggest that agencies may often give little feedback, but then periodically conduct audits that focus on small details, yielding somewhat inconsistent approaches that may give a mixed message and place IRBs in difficult and stressful situations. IRBs also vary in how they view, seek, receive, welcome, avoid, and/or fear federal input, and interact with agencies.

Researchers often blame frustrations they feel on IRBs (Koocher, 2005). Yet the present data highlight how IRBs serve as the “local face” of these federal regulations and agencies. Whereas researchers often see the IRB as the source of these frustrations, these IRBs themselves emerge as often “stuck in the middle” between regulatory bodies and PIs, having to implement and monitor regulations that they did not devise. Whereas, anecdotally, researchers may see IRBs as having considerable power, IRBs often see themselves otherwise—as instead being limited, stressed, and constrained by these external agencies. These data suggest larger power differentials in IRB interactions with governmental agencies, and indicate the need to see criticisms of IRBs in these larger contexts.

PIs may thus be “blaming the messenger” (i.e., the IRB) for perceived constraints imposed by the regulations, ascribing to IRBs varying and inconsistent interpretations of these regulations. This perspective (that PIs may “blame the messenger” rather than “the message”) is not to excuse IRBs if they apply regulations in unjustified ways. But greater appreciation of the actual contexts in which IRBs operate, and the pressures and strains they face—as individuals and social entities—can potentially help in addressing these difficulties, and facilitate IRBs and researchers working together as effectively as possible. This “systems perspective” can potentially help in understanding and addressing limitations and misunderstandings that IRBs confront. While many systems have effective feedback loops, the forms of feedback here may at times be inadequate and/or inefficient. Perhaps efforts to improve IRBs (e.g., ANPRM) should also assist IRBs in the interactions discussed here (e.g., establishing a hotline for IRB queries). In addition, the ANRPM appears to view IRBs as isolated entities, rather than as shaped by perceptions of, and interactions with, federal agencies. These data, if supported by further studies, suggest needs for further research concerning these issues, and potentially for OHRP to assist IRBs more.

Federal agencies may thus shape IRBs, which in turn affect PIs, and subsequently the treatment of research subjects. Yet, PIs can also complain about IRBs in ways that can affect federal regulations, as seen in the recent ANPRM, which grows in large part out of PIs’ complaints about these committees (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Anecdotally, subjects may not feel empowered to complain to institutions, and may thus do so rarely, if at all. Yet the death of a subject can lead to attention from the media and the federal government in a way that can force a major investigation and shutdown of an IRB or research at an institution. Events less dire than death (even injury of a subject that does not, however, result in death) may not trigger such feedback.

Underlying assumptions concerning the likelihood of researchers harming subjects, not complying with regulations, and conducting research irresponsibly may also contribute to problems with the status quo. But the interviewees here, all working on IRBs, tended not to question these underlying assumptions. These issues, too, can be explored in future research. While other federal regulations and agencies exist, these interviewees most often interacted with, and discussed, OHRP and the FDA, as reflected here. This paper sought to present the issues that interviewees themselves expressed.

Best Practices

These data have critical implications for practice. Federal agencies may not always reply as fully or timely as IRBs would like, exacerbating frustrations. Agencies may thus need to improve these interactions—to develop and evaluate possible structural and attitudinal interventions. For instance, agencies could potentially be required to respond to IRB communications within a set period of time. Federal agencies may often now respond to IRBs more frequently than interviewees feel occurs; but clearly, needs exist to investigate more fully how long agencies take to respond, what they communicate, what challenges they face in doing so, and why. Increased awareness of these issues and perceptions among agency staff and leaders, IRBs, institutional officers, and PIs can also potentially be helpful.

These data highlight needs to address not only what regulations consist of, but how exactly they are perceived, interpreted, and implemented at institutional and interpersonal levels. Heightened recognition of, and sensitivity to, these issues among agency and IRB personnel can potentially improve interactions and processes. Changes not only in formal structures, but also in informal relationships may be beneficial.

These data have implications for broader policy as well, particularly given ongoing debates and recent proposals for changing current regulations. ANPRM raises the possibility of several alterations to IRBs, but whether these will be implemented, and if so, how, to what degree, and with what outcomes and effectiveness will depend in part on the nature, quality, and effectiveness of relationships and interactions. These data highlight how regulations are not implemented and monitored in a vacuum, but in complex institutional systems. Agency responsiveness to local IRBs’ needs, and more timely and helpful input could perhaps be instituted. Other mechanisms for communication (e.g., perhaps more rapid, online forums) might assist, too.

These data pose critical questions concerning when and how frequently agency audits do and should occur. Agency resources may be too limited to interact with IRBs as fully as would be optimal, but these data then underscore the importance of increasing agency support. These data also suggest needs to examine how agency staff see their roles, what tensions they face, how they seek to resolve these conflicts, and with what success. Such further research may suggest ways to enhance these agencies’ relationships and interactions. These agencies could potentially serve as de facto appellates, but do not now appear to see themselves as officially and systematically filling this role—i.e., as negotiating disputes between IRBs and PIs.

Research Agenda

These data highlight the importance of examining IRBs in broader contexts—i.e., as embedded in complex dynamics with agencies and regulations that can shape IRB functioning and decisions. Moreover, these committees are not static, but can shift in response to these external factors, thus affecting IRBs’ interpretations and applications of regulations. Future studies can explore more fully with larger samples how IRBs differ in their perceptions of these agencies, and of their own roles as representatives of these external authorities. Such studies can probe the types of interactions IRBs have with federal agencies; the numbers, types, and reasons for federal audits each year; the types and content of requests for clarification that IRBs submit to these agencies; the nature and contents of answers agencies then provide; how long agencies take to respond; whether any one agency varies in its responses, and if so, how and why; and how agency staff view and approach these issues, whether they differ in responses to IRBs’ questions, and if so, how, when, and why. Future research can examine, too, whether, how often, and in what ways IRBs vary in perceiving these agencies (e.g., negatively vs. positively) and why; how IRBs respond to these pressures; what factors predict such variations (e.g., how IRBs may react to these agencies differently due to past experiences and psychological traits of chairs and/or vocal members); and how IRBs may approach PIs differently as a result. For instance, those IRBs that view their relationships with3agencies in more threatening or negative ways might take longer to review studies, and require more protocol changes. Interviewees did not appear to differ systematically here in their views regarding these issues, based on their roles (e.g., chair vs. administrator), but future research can explore, too, possible such differences in larger samples. Future studies can also probe more fully the cost-effectiveness of different types and extents of audits. I have found no published empirical data examining these issues.

Educational Implications

These data have several important implications for education, too—to increase awareness of these issues among IRB chairs, members and staff, PIs and policy-makers. Some of these interviewees’ statements may suggest a lack of knowledge and sophistication in understanding the federal process. But these statements nonetheless express these individuals’ views and understandings, and thus suggest needs for requirements for education of IRB chairs, members, and staff—perhaps government-mandated tests using standardized protocols. Currently, no governmental requirement exists for education of IRBs. Though IRB staff may seek voluntary certification, not all do so, and certification is not based on assessment of correct responses in reviews of standardized protocols. Federal officials should also become more aware of how aspects of the quality and quantity of their interactions with IRBs can affect IRBs in diverse ways. Education of PIs about the complexities of these systems may be beneficial, so that they do not blame the IRB for the regulations, and do not seek to avoid federal requirements because of frustration and perceived unfairness of individual IRBs.

Potential Limitations

These findings have several potential limitations. These interviews explored subjects’ views now and in the past, but not prospectively over time to examine possible changes. However, further studies can do so. These statements represent these interviewees’ perceptions and may not reflect the entire “objective reality,” but are nonetheless valuable in and of themselves, suggesting problems that may need to be addressed. These data are also based on in-depth interviews with individual IRB chairs and members, and did not include direct observations of IRBs as a whole, or examination of written IRB records. Future research can, however, observe IRBs and examine such documents. However, such added data may be hard to procure since, anecdotally, IRBs have often required researchers first to obtain consent from all IRB members, the PIs, and protocol funders. Future studies can also interview federal agency staff about these issues. This study is qualitative, and hence is designed to probe—in ways that quantitative research cannot—beliefs, views, attitudes, and relationships between those phenomena, to yield research questions and hypotheses that future studies can explore in further detail using larger samples and quantitative approaches. This qualitative research was not designed to measure responses quantitatively, but further investigations can do so.

In sum, these data have critical implications for future policy, practice, research, and education, especially given ongoing debates as to whether the current system should be changed, and if so, how. These data suggest that it is important that IRBs be seen as operating in complex institutional contexts, and as having dynamic relationships with federal agencies that may affect IRB decisions.

Acknowledgments

The NIH (R01-NG04214) and the National Library of Medicine (5-G13-LM009996-02) funded this work. The author would like to thank Meghan Sweeney, Jason Keehn, Renée Fox, Paul Appelbaum, and Patricia Contino for their assistance with this manuscript.

Biography

Robert Klitzman is Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, Director of the Masters of Bioethics Program, and Director of the Ethics & Policy Core of the HIV Center at Columbia University. He has conducted research on several aspects of research ethics.

References

- Begun JW, Zimmerman B, Dooley K. Health care organizations as complex adaptive systems. In: Mick SM, Wyttenbach M, editors. Advances in health care organization theory. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MD. The illusion of clarity: A critique of “pure” clarity using examples drawn from judicial interpretations of the Constitution of the United States. In: Wagner A, Cacciaguidi-Fahy S, editors. Obscurity and clarity in the law: Prospects and challenges. UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burris S. Regulatory innovation in the governance of human subject research: A cautionary tale and some modest proposals. Regulations and Governance. 2008;2(1):65–84. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: Scientists talk about the ethics of research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2006;1(1):43–50. doi: 10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop BW, Banja J. A renewed, ethical defense of placebo-controlled trials of new treatments for major depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2009;35(6):384–389. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.028357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak K, Anderson R, Sevick MA, Weisman CS, Levine DW, Scholle SH. Variations among institutional review boards in a multisite health services research study. Health Services Research. 2005;40(1):279–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Menikoff J. Reforming the regulations governing research with human subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(12):1145–1150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1106942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emirbayer M. Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;103(2):281–317. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott T. Law is necessarily vague. Legal Theory. 2001;7:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D. The use of placebo-controlled clinical trials for the approval of psychiatric drugs: Part I—Statistics and the case for the “greater good. Psychiatry MMC. 2009;6(3):41–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman AR. Regulating research with human subjects: Is the system broken? Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2005;116:91–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost N, Levine RJ. The dysregulation of human subjects research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(18):2196–2198. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Greene SM, Geiger AM. A review finds that multicenter studies face substantial challenges but strategies exist to achieve institutional review board approval. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(8):784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger P. The new censorship: Institutional review boards. University of Chicago; 2005. Public Law Working Paper No. 95. Retrieved April 6, 2011 from http://ssrn.com/abstract=721363. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer CA, Petty J. Bureaucratic ethics: IRBs and the legal regulation of human subjects research. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 2010;6(1):601–626. [Google Scholar]

- Howick J. Questioning the methodologic superiority of “placebo” over “active” controlled trials. American Journal of Bioethics. 2009;9(9):34–38. doi: 10.1080/15265160903090041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R. U.S. IRBs confronting research in the developing world. Developing World Bioethics. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00324.x. Published ahead of print April 19 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R. “Members of the same club”: Challenges and decisions faced by U.S. IRBs in identifying and managing conflicts of interest. PLoS ONE. 2011a;6(7):e22796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022796. Published online July 29, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R. How local IRBs view central IRBs in the U.S. BMC Medical Ethics. 2011b;12(13) doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-12-13. Published online June 23, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R. Views and experiences of IRBs concerning research integrity. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2011c;39(3):513–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R. The myth of community differences as the cause of variations among IRBs. American Journal of Bioethics. 2011d;2(2):24–33. doi: 10.1080/21507716.2011.601284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koocher GP. The IRB paradox: Could the protectors also encourage deceit? Ethics and Behavior. 2005;15(4):339–349. doi: 10.1207/s15327019eb1504_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulynych JD, Korn D. The new HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) medical privacy rule: Help or hindrance for clinical research? Circulation. 2003;108:912–914. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080642.35380.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E, Bratts T, Zwanziger J, Stone P. A survey of IRB process in 68 U.S. hospitals. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(3):260–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughren TP. The scientific and ethical basis for placebo- controlled trials in depression and schizophrenia: An FDA perspective. European Psychiatry. 2001;16(7):418–423. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidz CW, Simon LJ, Seligowski AV, Myers S, Gardner W, Candilis PJ, Arnold R, Appelbaum PS. The participation of community members on institutional review boards. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2012;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams R, Hoover-Fong J, Hamosh A, Beck S, Beaty T, Cutting G. Problematic variation in local institutional review of a multicenter genetic epidemiology study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(3):360–366. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menikoff J. The paradoxical problem with multiple-IRB review. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(17):1591–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons T. The social system. New York: The Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Schrag Z. Ethical imperialism: Institutional review boards and the social sciences. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silbey SS. The sociological citizen: Pragmatic and relational regulation in law and organizations. Regulation and Governance. 2011;5(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stark L. Behind closed doors: IRBs and the making of ethical research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Human subjects research protections: Enhancing protections for research subjects and reducing burden, delay, and ambiguity for investigators. 2011 Retrieved April 19, 2012 from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-07-26/pdf/2011-18792.pdf.

- Von Bertalanffy L. An outline of general system theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 1950;1(2):134–165. [Google Scholar]