Abstract

Objectives

Recognizing the need to work with all partners who have an interest in addressing sexual health issues, we explored values held by diverse stakeholders in the United States. Based on these findings, we developed a framework for use in communicating about sexual health issues and potential solutions.

Methods

Our methods included an environmental scan, small-group metaphor elicitation and message framing assessments, interviews, and online surveys with diverse members of the public and health professionals.

Results

Of four overarching value-based themes, two were best accepted across audiences: the first theme emphasized the importance of protecting health along the road of life through enabling good choices, and the second called for adding health promotion approaches to traditional disease prevention control. Nearly all supporting statements evaluated were effective and can be used to support either of the two best accepted overarching themes.

Conclusions

Although there is a great diversity of opinion regarding how to address sexual health issues in the U.S., among diverse stakeholders we found some common values in our exploratory work. These common values were translated into message frameworks. In particular, the idea of broadening sexual health programs to include wellness-related approaches to help expand disease control and prevention efforts resonated with stakeholders across the political spectrum. These findings show promise for improved sexual health communication and a foundation on which to build support across various audiences, key opinion leaders, and stakeholders.

While many individuals in the United States are sexually healthy and experience positive, life-enriching relationships, diseases and life-threatening conditions related to sexuality and sexual behavior are a serious problem. An estimated 19 million new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) occur each year,1 with one in four adolescent girls aged 14–19 years being infected with at least one STI.2 In addition, approximately half of all pregnancies are unintended,3 and one in five U.S. women report having been the victim of sexual violence.4 At the same time, communication about sexual health among individuals, couples, families, and communities is infrequent; for example, among adolescents aged 15–24 years, only 19% of females and 13% of males reported discussing key sexual health topics with their parents.5 It will require work at all levels of society to move from a traditionally sexual disease-focused model to a health-focused framework to tackle these problems.6,7

Opinions on how to address sexual health issues are diverse, reflecting the wide-ranging values of individuals and groups seeking solutions. In response to the 2001 “Surgeon General's Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior”8—which recognized that a national dialogue at all levels of society is critical to improve population health—the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, sponsored the National Consensus Process on Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behaviors (NCP). In 2006, the NCP released an Interim Report documenting agreement by diverse stakeholders on a framework for action and aspects of sexual health that should be addressed.9 The report suggests that communication plays a critical role in how individuals and groups can work together in this arena, noting that “Words can have multiple meanings that complicate dialogue. . . [and] how difficult it can be to dialogue about deeply held perspectives.. . .”

In recent years, a number of organizations working in public health have applied theories and evidence, such as framing theory and market research, from the fields of cognitive science, psychology, and communication to find ways for diverse advocates to articulate the need for new approaches in addressing health issues. In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), with its partners, initiated work to develop overarching messages to reframe the public's understanding of how injuries and violence place a health burden on society.10 In 2007, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) also commissioned work to study how stakeholders across the political spectrum perceived the impact of social determinants of health, and how the values held by different groups framed their understanding of these factors.11 Both of these projects identified how communication chasms could be bridged, and they developed messaging guidelines.

Recognizing the need to work with all partners who have an interest in addressing sexual health issues, and using best practices and findings from both the NCIPC and RWJF projects, in 2010 the CDC's National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) commissioned the American Institutes for Research (AIR) to explore values held by diverse stakeholders working to address sexual health issues in the U.S. The goal of the project was to develop a framework for multiple stakeholders to use in communicating about sexual health based on identified common values.

METHODS

Overview

We used framing theory to help shape how we translated the values and concerns of our diverse stakeholders into message frameworks, messages, and specific statements, using the notion of levels of framing advanced by Lakoff,12,13 who argues that achieving agreement and connection to high-level values (e.g., fairness or responsibility) is critical to successful communication. We also relied on the long history of related communication and framing research from the marketing arena and sought to engage a wide range of stakeholders, with attention to differing opinions or perspectives regarding sexual health.14–16 We conducted a sequence of exploratory research activities to discover the values and concerns of these diverse stakeholders, translate findings into messages, and test messages across different audiences.

Environmental scan

We conducted an environmental scan to create an inventory of significant articles representing the current dialogue on sexuality and sexual health in the U.S. The search included both a national media scan and a literature review across 11 databases: Academic Search Premier, Cochrane Library, EBSCO, HSRProj (Health Services Research Projects in Progress), JSTOR Data for Research, Nexis, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Reuters, PsycINFO, PubMed, and SocINDEX. Members of the team reviewed each article title and, where necessary, abstracts and key search terms in context to determine relevance. These abstracts or articles were then reviewed for key themes, topics, tone, and audience to inform the stakeholder consultations.

Stakeholder consultations

The team conducted small-group consultations featuring unstructured and semistructured dialogue, one each for external stakeholders and internal CDC stakeholders. For the external stakeholder engagement, representatives from six diverse national groups involved in sexual and reproductive health issues were invited to spend a day with CDC. For the internal consultation, we invited 10 staff members from CDC divisions working on aspects of sexual health (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, sexually transmitted diseases, viral hepatitis, adolescent/school health, reproductive health, and sexual violence).

During the external stakeholder consultation, participants shared stories and quotes that reflected their personal philosophies and talked about their organization's work and fundamental values. They also shared their experiences of implementing sexual health programs and what they thought CDC should consider in shaping future initiatives. During the internal stakeholder meeting, the facilitator used summaries of results from the environmental scan and perspectives from external stakeholders to spur reflections on the implications of a more integrated approach to improving sexual health outcomes.

To facilitate discussion, the team developed a list of unstructured paragraphs and statements regarding sexual health and general ideas on how to improve sexual health outcomes. Statements within paragraphs were drawn from a combination of the environmental scan findings and metaphors related to addressing health and public issues in society identified in the work of CDC's NCIPC and the RWJF.

Both consultations concluded with participants reviewing the unstructured paragraphs and marking phrases as to whether they were acceptable or unacceptable, raised questions or problems, were clear or murky in meaning, or invoked neutral responses. Discussions were held with each group to identify commonly held values, clarify points, and facilitate more dialogue about the topics.

Message development and testing

Message development.

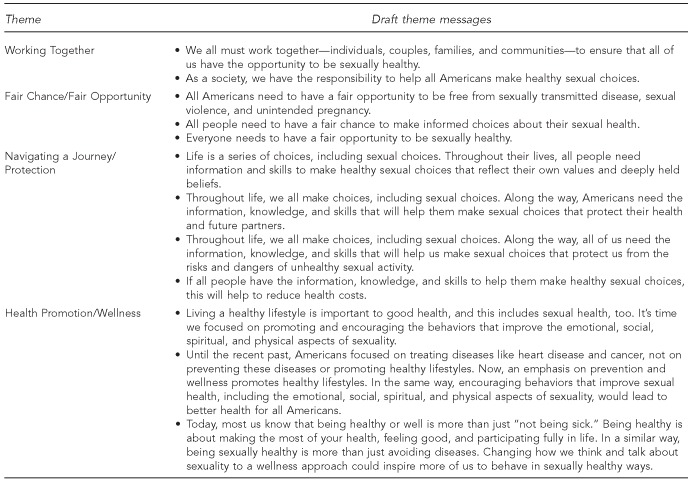

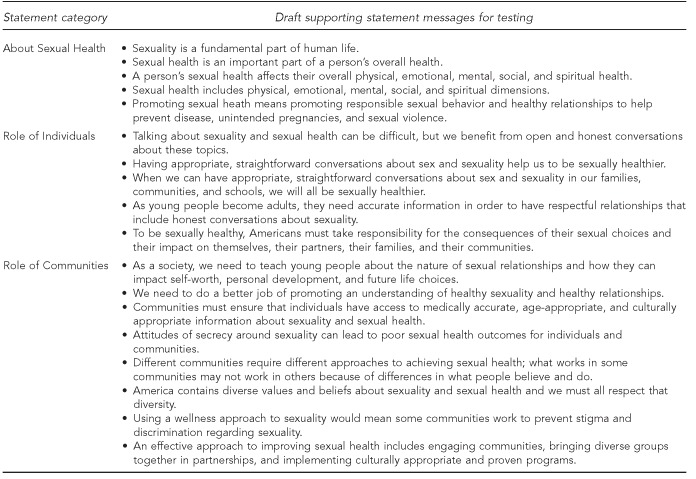

Following the consultation meetings, the AIR team worked with NCHHSTP to develop four overarching themes (i.e., overarching ways of talking about sexual health) and three sets of supporting statements on various sexual health aspects. A total of 30 messages featuring different wording choices for themes and supporting statements were developed for testing, as presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Draft themes and messages for testing in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

Figure 2.

Draft supporting statements for testing in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and American Institutes for Research, 2011

In the exploratory message testing activities, we varied the order of the differently worded overall themes and supporting statements to eliminate ordering bias. In the activities, we used CDC's Health Message Testing System (HMTS),17 which incorporates required CDC data collection and Institutional Review Board (IRB) processes in its protocol; AIR also completed an IRB review.

Interviews with professionals by telephone.

Cognitive interviews were conducted with a wide range of professionals, including health care, community organizers, academicians, and opinion leaders. Interviewers used cognitive interviewing techniques to develop an understanding of how people process, understand, and might use the information. The technique allows for just-in-time reactions to messages by asking participants to verbalize their thoughts. Participants also answer direct questions so interviewers can learn how interviewees interpreted the language used. We recruited 26 individuals using snowball sampling techniques, taking care to recruit respondents who might present differing viewpoints.

Web-based surveys with the general public and professionals.

We conducted surveys, fielded by a vendor specializing in online panels, to test the revised messages with a larger sample of both the public and professionals. Questions were selected from CDC's HMTS, which offers a library of open- and closed-ended survey items to gather input on impressions, personal relevance, content and wording, efficacy, and dissemination channels. Each message was scored for multiple characteristics (i.e., effective, attention-grabbing, convincing, trustworthy, and important). The theme deemed best accepted by respondents was selected by analyzing which related messages scored highest across message characteristics and did not provoke marked negative reactions.

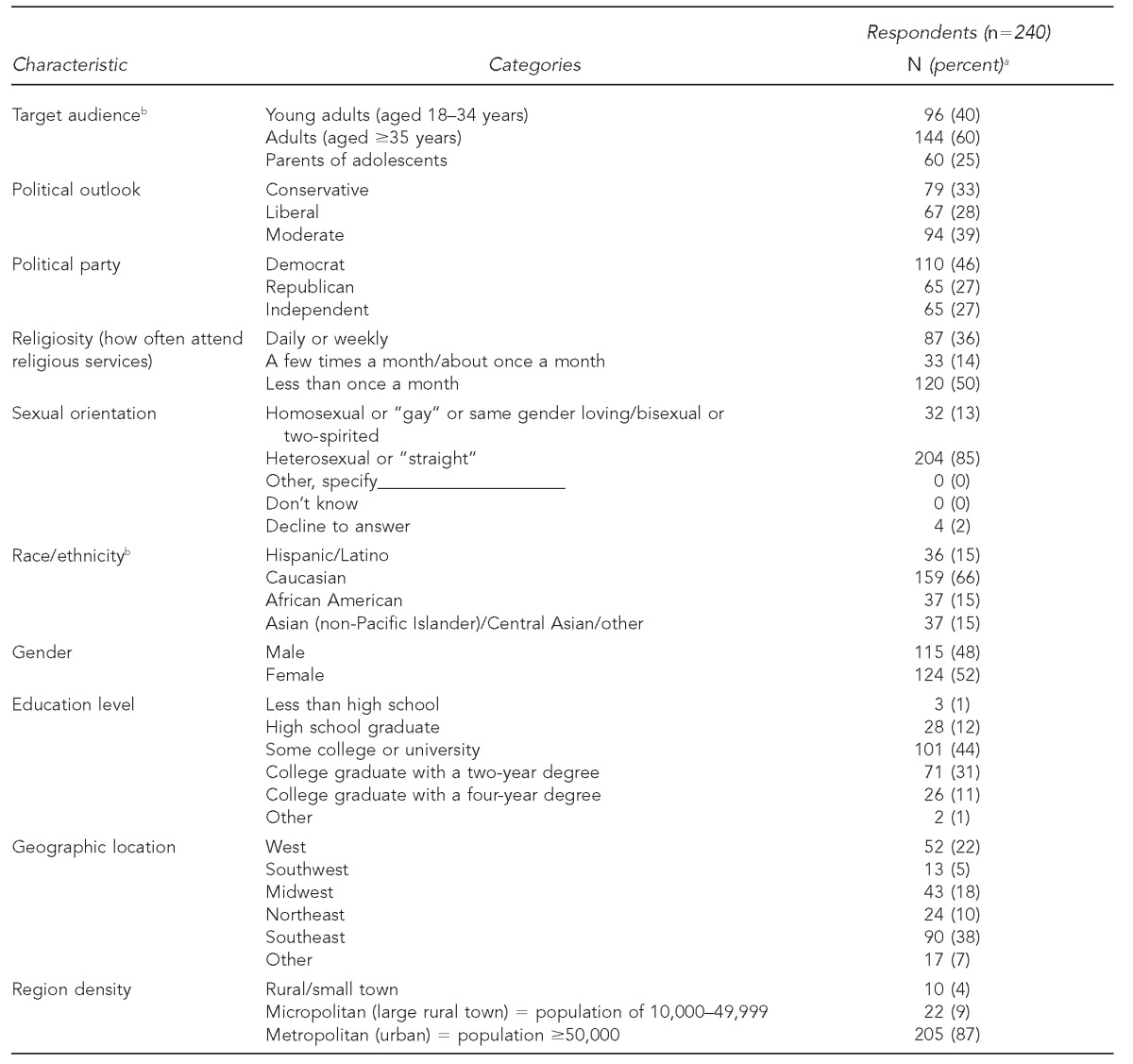

A total of 240 general public respondents were randomly selected from the vendor's general public database. The public sample had diverse demographic, geographic, religious, ideological, political, sexual orientation, gender, and social backgrounds, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics of a sample of the general public surveyed in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

aSome categories do not total 240 due to missing responses. Percentages are based on total number of responses in each category.

bThe categories in these characteristics are not mutually exclusive.

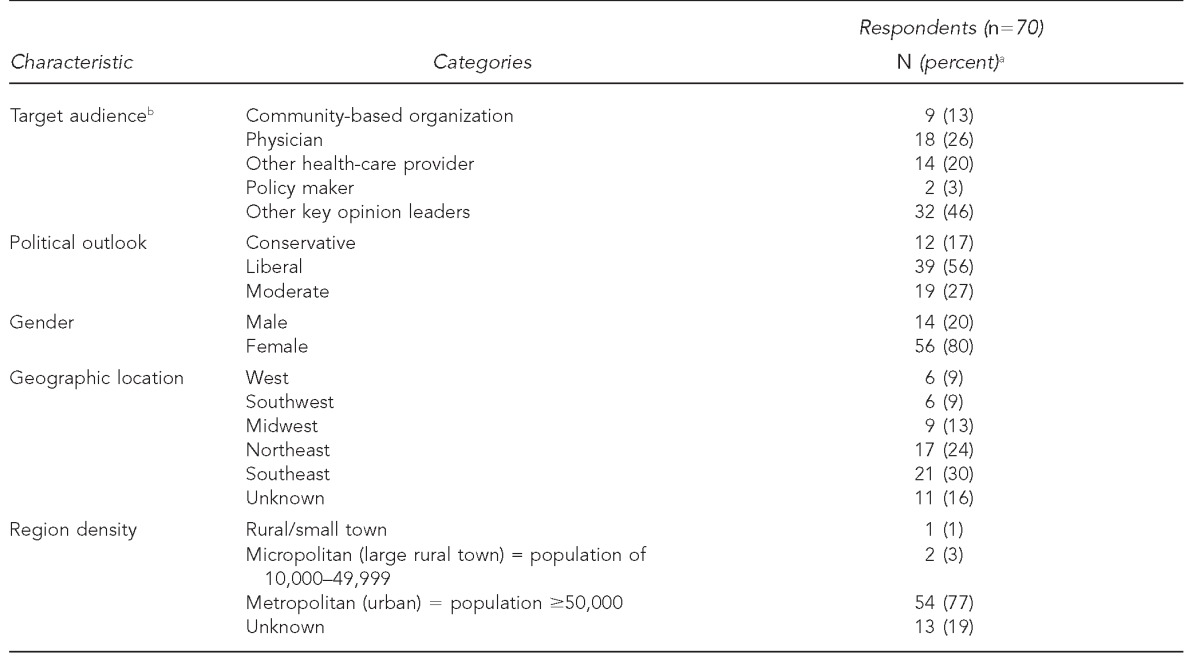

As detailed in Table 2, a sample of 70 professional respondents who work in health-related fields completed the same online survey. To identify professionals, AIR used snowball sampling, collecting referrals from telephone interviewees and survey respondents. The professionals in the sample included both men and women and a diverse set of professions, political outlooks, geographic locations, and community densities.

Table 2.

Respondent characteristics of a sample of health-care and other key professionals surveyed in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

aPercentages may not total 100 due to rounding.

bThe categories in this characteristic are not mutually exclusive.

The resulting quantitative survey data was analyzed using SAS® version 9.2, with descriptive statistical analyses for each item.18 We tested categorical variables regarding respondent characteristics such as ethnicity, as well as the relationship between respondent characteristics and responses to particular messages, using Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests to look for significant differences in responses among types of respondents.

RESULTS

Environmental scan

The scan produced more than 12,000 articles with a final sample consisting of 539 articles. Much of the analyzed content focused on the negative implications of sexual diseases. In articles with a negative tone, sexuality was sometimes cast as unhealthy excess or in terms of illegality. However, in articles with a positive tone, the benefits of having “good sex” were often discussed in terms of contributing to well-being and happier lives. Common among many articles were discussions of responsibility and of sexual health as a choice. We found multiple uses of imagery of fighting, battles, and war against sexual health risks. Among the minority of articles that proposed solutions, articles discussing sexual health education and parents' responsibilities most often offered open communication as a solution.

Stakeholder consultations

While there was no universal consensus among stakeholders, we did find strong agreement on a number of messaging issues: participants in both external and internal groups spoke of valuing accurate, objective information about sexual health, and about increasing dialogue among those with differing opinions and beliefs. Participants in both meetings rejected words and phrases that they believed to be ambiguous, in particular words that “allow people to define terms on their own,” often because they suspected that the author's intent could be one that the participants would reject. Example words and phrases included “responsible,” “committed,” “age-appropriate,” and “healthy relationship.” Both groups called for more clarity in the statements and paragraphs. Participants in both groups liked language that described “a diverse nation, with many backgrounds, cultures, faiths, and deeply held beliefs.” Most participants liked the analogy of sexual health to overall health and wellness. The theme that aligned sexual health with one's life journey was also favorably reviewed. Many participants called for a balance between talking about individual responsibilities and consequences, and community- and society-level responsibilities and consequences.

Interviews and online surveys

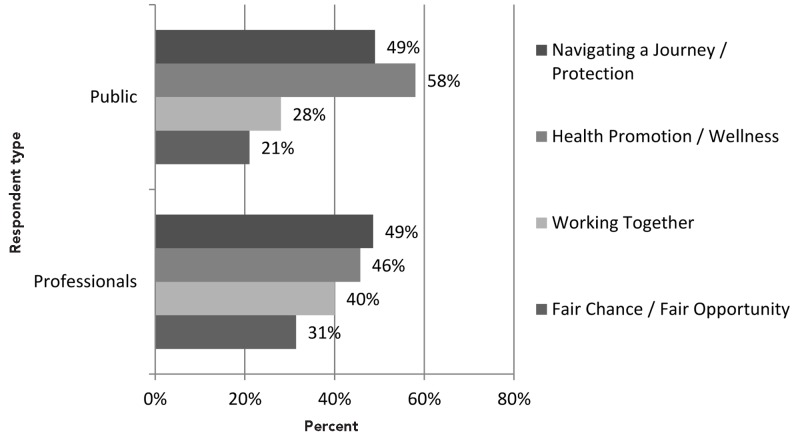

The results from interviews with professionals and surveys with the public and professionals were consistent, with interview findings providing greater understanding of the selections survey participants made. Results clearly indicated two resonant themes across a wide range of stakeholders: “Navigating a Journey/Protection” and “Health Promotion/Wellness,” represented by differently worded statements (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Most accepted themes by general public and professional respondents in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

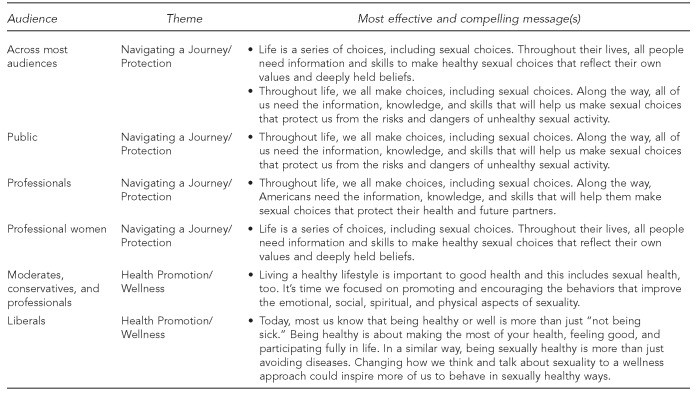

The only statistical differences on the top two themes were between political outlook and gender (for professionals only). There was broad-based acceptance of the Navigating a Journey/Protection theme, as it was effective across the public and professional audiences without offending or alienating any audience. However, there were two variations on the Navigating a Journey/Protection theme that tested well—one with professional audience members and another with the public (Figure 4). Further, professional women preferred one variation more often than professional men (Figure 4). The Health Promotion/Wellness theme also resonated well across most of the public and professional audiences. However, moderates, conservatives (identified for the general public through self-report: “Do you consider yourself liberal, moderate, or conservative?”), and professionals were more likely to prefer one Health Promotion/Wellness message choice or wording, while liberals were more likely to prefer a different message choice or wording for that theme (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effective and compelling themes and messages by audience in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

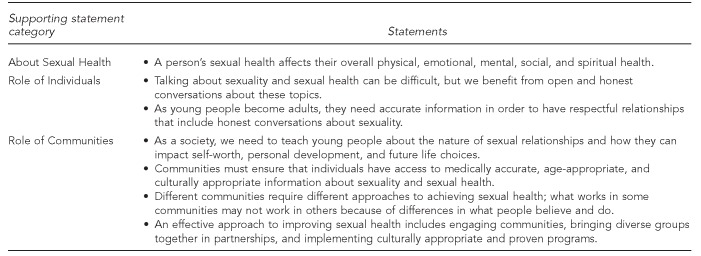

Message testing of the supporting statements showed that they were nearly all acceptable and can be used to support either of the two best overarching themes. The supporting statements that scored the highest across audiences are presented in Figure 5. In the “About Sexual Health” category, the statement “A person's sexual health affects their overall physical, emotional, mental, social, and spiritual health” was the most acceptable choice across public and professional audiences. Under the “Role of Individuals” category, the statement “Talking about sexuality and sexual health can be difficult, but we benefit from open and honest conversations about these topics” was selected most often across all audiences. For the “Role of Community” category, several statements were selected as effective across a broad range of audiences. Of the 17 supporting statements tested, we found statistically significant differences in the acceptability of five specific statements: by education for About Sexual Health; by race for Role of Individuals; and by sexual orientation, regional density, or professional type for three separate statements under Role of Community. For example, respondents with a high school diploma or less education tended to select the message “Sexuality is a fundamental part of human life” as effective more often than those with a college degree or higher education.

Figure 5.

Recommended supporting statements for use across all audiences in a project to develop a communication framework for sexual health: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Institutes for Research, 2011

We included two questions in our surveys on the appropriateness of CDC as a source of sexual health information and CDC's trustworthiness. We found that public (n=240) and professional (n=70) participants overwhelmingly thought that CDC was a good, trustworthy, believable source for this information. A very small group of respondents (less than 4% of the public respondents and about 6% of professionals), primarily moderates and conservatives, felt otherwise.

DISCUSSION

The results from interviews with professionals and the survey with the public and professionals were consistent and clearly indicated that two overarching themes—Navigating a Journey/Protection and Health Promotion/Wellness—were best accepted across a wide range of stakeholders. Because the themes “Working Together” and “Fair Chance/Fair Opportunity” did not score as well across audiences, we do not recommend the messages from these themes as ways to begin a dialogue or communicate about sexual health.

In contrast to the RWJF study—for which both the Fair Chance/Fair Opportunity and Navigating a Journey/Protection themes scored well across conservative and liberal audiences in speaking of social determinants of health—the Fair Chance/Fair Opportunity theme did not score well in our study, while the Navigating a Journey/Protection theme did. One explanation is that underlying stakeholder values vary by contexts of use. That is, the acceptability of a specific theme may be strengthened or weakened based on the specific health topic to which it is applied.

Limitations

Several factors limited the findings of this study. First, the use of qualitative data collection techniques presented some limitations. For example, aggregating responses from qualitative data collection requires interpretation by analysts, and one analyst's interpretation may differ from another's. However, our tests for reliability of the coding suggested this was not a serious source of bias. Also, although we controlled for ordering bias by changing the presentation order of the themes and supporting statements during the telephone interviews, we did not vary the order of the messages within each theme or within the sets of supporting statements.

Quota sampling was used to recruit public survey participants. However, there were a limited number of respondents in some characteristics, specifically the number of Asian respondents, those with less than a high school education, those living in the Southwest, and those living in rural or micropolitan areas. Our sample also had a limited number of policy makers, conservatives, males, and those living in rural or metropolitan areas in the professional audience survey. Therefore, we could not make statistically reliable comparisons for these respondent characteristics due to the small sample size. Further, for analysis of the professional survey, due to the small sample size, moderate and conservative audiences were combined to allow us to make statistically reliable comparisons.

In both surveys, we were limited to questions from CDC's HMTS, which presented constraints in survey wording choices. For example, in the public survey, we had access to variables from self-reported items that identified the respondent as liberal, moderate, or conservative. But for the professional survey, we did not have these variables available; rather, proxy questions related to respondents' positions on social issues, such as same-sex marriage and abortion, were used to categorize the professionals as conservative, moderate, or liberal.

Lastly, the purpose of the study was to explore stakeholders' values and perspectives about sexual health to identify potential message frameworks for use in communicating about sexual health issues and potential solutions. The nature of the research was exploratory and the results are not generalizable. The frameworks are general in nature and are not appropriate for use as the sole messaging in a specific sexual health campaign.

CONCLUSIONS

The two themes, Navigating a Journey/Protection and Health Promotion/Wellness, may be used as a starting point for tailoring messages to a specific context and audience. The frameworks would need further study and message testing within the context of any specific campaign. Further, tailoring messages and supporting statements for specific audiences—particularly where statistically significant differences exist—may generate a stronger response by that audience. This work is a useful starting place for additional studies to extend these findings to specific audiences and contexts. Future research might analyze sexual health conversations that take place in media or political venues, including discussions of contraception and sexual violence, to test how the themes identified in our study could generate messaging around these topics.

The work described in this article represents the first study to systematically develop messages regarding sexual health by identifying common values across diverse stakeholders and audiences to improve communication. While this study did have several limitations, its scope and scale were sufficient to state that we achieved our goal of identifying values and appealing messages across stakeholders and audiences regarding sexual health. In particular, the idea of extending sexual health programs beyond disease control and prevention approaches into the health promotion/wellness arena resonated with stakeholders across the political spectrum. Both the CDC's NCIPC and the RWJF used findings from their studies to develop guides in their respective areas of work for stakeholders to use in improving the quality and consistency of messages. We plan to use our findings similarly to develop tools to aid sexual health communication efforts across various audiences, key opinion leaders, and stakeholders, so that they may continue to build support, visibility, and momentum for the field.

Footnotes

The authors thank all the stakeholders who offered their perspectives during this evaluation and our colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American Institutes for Research (AIR) who provided additional technical assistance during the study. This study was approved by the AIR Institutional Review Board.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1505–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2011. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Center for Health Statistics (US) National Survey of Family Growth. [cited 2012 Feb 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Atlanta: CDC; 2010. A public health approach for advancing sexual health in the United States: rationale and options for implementation: meeting report of an external consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenton KA. Time for change: rethinking and reframing sexual health in the United States. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):S250–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Office of the Surgeon General. Washington: HHS, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. The Surgeon General's call to action to promote sexual health and responsible sexual behavior. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Consensus Process on Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. Atlanta: Morehouse School of Medicine; 2006. [cited 2010 Dec 6]. Interim report. Also available from: URL: http://www.msm.edu/Files/CESH_NCP_InterimReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Atlanta: CDC; 2008. Adding power to our voices: a framing guide for communicating about injury. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiano A, Westen D, Carger E. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. A new way to talk about the social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakoff G. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1996. Moral politics: what conservatives know that liberals don't. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakoff G, Morgan P. [report to the Ford Foundation; Rockridge Strategic Analysis Paper 2001-01]. In: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Innovations in American Government, Innovations in American Government. Public obligations: giving kids a chance [report from a conference on the state role in early education]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 2001. Framing social issues: does “the working poor” work? pp. 16–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen GL, Olson JC. Mapping consumers' mental models with ZMET. Psychol Marketing. 2002;19:477–502. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaltman G. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press; 2003. How customers think: essential insights into the mind of the market. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulter RA, Zaltman G, Coulter KS. Interpreting consumer perceptions of advertising: an application of the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique. J Advert. 2001;30:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2009. Jul, Health Message Testing System question bank [OMB No. 0920-0572] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute Inc. SAS®: Version 9.2. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]