Abstract

Oregon's work on teen pregnancy prevention during the previous 20 years has shifted from a risk-focused paradigm to a youth development model that places young people at the center of their sexual health and well-being. During 2005, the Oregon Governor's Office requested that an ad hoc committee of state agency and private partners develop recommendations for the next phase of teen pregnancy prevention. As a result of that collaborative effort, engagement of young people, and community input, the Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan was released in 2009. The plan focuses on development of young people and embraces sexuality as a natural part of adolescent development. The plan's five goals and eight objectives guide the work of state agencies and partners addressing youth sexual health. Oregon's development of a statewide plan can serve as a framework for other states and entities to address all aspects of youth sexual health.

Sexual health in adolescents and young people (hereafter, youth sexual health) has been defined as the physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being, regarding sexuality, of people aged 10–19 years.1 Consideration of the health risks, services, and needs as unique for adolescents is a relatively new concept;2 youth sexual health was first described as a basic right during the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD). The ICPD adopted a 20-year Programme of Action, which included sexual health as a part of the definition of reproductive health, and was described as “the enhancement of life and personal relations, and not merely counseling and care related to reproduction and sexually transmitted diseases.”3,4 The language used in the definition indicated a more holistic consideration of sexual health comprising prevention and health promotion. Certain strategies have been identified that together support and promote sexual health in young people: youth-friendly clinical services (e.g., those that are designed to attract young people and reduce barriers to use),5 comprehensive sex education programs, and development programs that engage young people and promote protective factors.4

Changing to a holistic, health-promotion model has been difficult. Until 2010,6 dedicated teen pregnancy prevention funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families placed major emphasis on supporting abstinence-only education.7 However, as of 2009, the Community Preventive Services Task Force concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against abstinence-only education.8

The National Commission on Adolescent Sexual Health (NCASH) recommends that policy makers “develop public policies consistent with research about adolescent development, adolescent sexuality, and program effectiveness.” To best support well-being in young people, Oregon has pursued efforts to create policies that reflect NCASH's comprehensive definition of youth sexual health, which “encompasses sexual development and reproductive health, as well as such characteristics as the ability to develop and maintain meaningful interpersonal relationships; appreciate one's own body; interact with both genders in respectful and appropriate ways; and express affection, love, and intimacy in ways consistent with one's own values.”9 This article describes the process of developing Oregon's youth sexual health plan, which can serve as a guide for agencies that work to create, develop, and implement programs and policies that affect young people.

BACKGROUND

Oregon is entering its third decade of including teen pregnancy prevention as part of a statewide health-care policy agenda. Three statewide teen pregnancy prevention plans were released from 1994–2002. The language of each subsequent plan de-emphasized a risk-based approach, transitioning toward a health-promotion model of youth sexual health.10 Oregon laws that supported teen pregnancy prevention efforts included required content for human sex education11 and minors' rights to access care (e.g., for those aged <18 years).12,13

The sex education law emphasized abstinence and included information regarding disease prevention and birth-control methods. This law was referred to as an if/then statute, meaning that if public schools offered sex education, then they were required to teach topics outlined in the statute. School districts could choose to not offer any sex education.

State laws regarding young people's access to health-care services met the best-practices standards of the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics. A limited number of Oregon statutes addressed minors' rights; without parental consent, minors aged ≥ 15 years are permitted access to medical and dental services, and all minors are allowed to access birth control-related information and services, as well as testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).12,13

Although these laws were in place, Oregon had encountered increased polarization of opinions among elected officials and the public regarding sexual health concerns. Specifically, a lack of coordinated multi-agency collaboration and debates between abstinence-only advocates and comprehensive sex education proponents hindered progress toward a unified vision for youth sexual health. To align efforts, the Oregon Governor's Office requested in 2005 that state agency representatives, together with private partners, develop recommendations for the next phase of teen pregnancy prevention in Oregon. This ad hoc committee recognized the opportunity to review the science, develop a coordinated approach, and resolve philosophical differences.

The committee recommended that a permanent statewide partnership be formed to create a new strategic plan, provide leadership for its implementation, and develop ongoing policy recommendations. The transitional name for the committee was Teen Pregnancy Prevention/Sexual Health Partnership, which acknowledged the broader context of healthy sexuality. The committee, which provided Oregon with the beginnings of the current Oregon Youth Sexual Health Partnership (OYSHP),13 broadened the traditional concept of teen pregnancy prevention to an all-encompassing frame of youth sexual health and established the groundwork for creating a new youth sexual health plan. The Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan, released in 2009, was the first initiative to formally broaden what was historically labeled “teen pregnancy prevention” to that of youth sexual health.

METHODOLOGY

Development of the plan relied on the use of data and evidence-based or promising practices. The committee was directed to design a state plan that (1) acknowledged that sexual health is a component of overall health and is connected to wider societal concerns; (2) emphasized that adults have a responsibility to ensure that young people receive developmentally appropriate and accurate information, as well as services that support the ability for young people to make healthy choices;14 (3) recognized that parents are important partners in this effort; and (4) acknowledged that an opportunity exists for all populations to become better informed regarding sexual health. Two strategies—community engagement and youth participatory research—were foundational in this process.

The plan was designed by using a consensus-driven model of stakeholders including a coalition of state and county agencies, community advocates, nonprofit organizations, and young people. Through a process facilitated by the Oregon Public Health Division (OPHD) and the Children, Adult and Family Division of the Oregon Department of Human Services, five long-term goals and eight objectives for state and community action were identified.

Developing specific content and strategies for each objective was guided by core activities that included young people's action research, statewide community forums, a community opinion survey, and a review of literature and theory. Oregon's data related to teen pregnancy, births, STIs, and teen sexual risk behaviors were provided as background at each community forum. OYSHP member agencies variously contributed to financing, staff time, technical assistance, printing, and facilities to support the core activities of plan development.

Youth action research

Youth action research (YAR), a model curriculum developed by OPHD, represents an empowerment form of community participatory research geared toward young people that in this instance focused on youth sexual health. YAR was a centerpiece of our commitment to engaging young people. The model teaches principles and skills of community-based research, provides opportunities for young people to use that research for community education, and can drive policy and social change at the local level (e.g., increasing access to condom availability and family planning services).

Action research projects took place in Multnomah, Jackson, and Deschutes counties. Twenty-two students in grades 11 and 12 were trained as researchers. Training included information regarding research methods, protocols and design, data collection, and data analysis. Young researchers used classroom-based surveys and focus groups to gather input from more than 2,000 young people and presented their findings and recommendations at community forums. Results from across the three communities illuminated young people's desire to receive more information about healthy relationships and to have more opportunities for conversations with a parent about sexual development. Such conclusions from YAR results are represented in the final content of the state plan.

Community forums

The statewide partnership organized and conducted nine community forums in rural, suburban, and urban locations throughout Oregon. Forum facilitators presented county-level data and YAR results, asked questions regarding priority concerns, and suggested ways to improve sexual health. The forums, which included adults and young people, were designed to reach diverse populations. A total of 881 people participated in the process. The issues and solutions identified by forum participants reflected a need to provide more sexual health education and to have that education be more about relationships and human interactions rather than merely the mechanics of reproduction. Conclusions from the forums were incorporated into the plan.

Issue briefs

To provide accurate information to community forum participants, a limited number of research briefs were developed.15 The briefs, which were summaries of relevant research, included Oregon-specific data on a wide variety of topics from the most recent Oregon Healthy Teens Survey,16 Oregon's version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. The briefs educated YAR and community forum participants and informed the development of the plan. Topics included teen brain development, teen pregnancy, STIs, dating violence and sexual assault, health inequities, parental -involvement and youth-adult connectedness, and contraception and sexual protection.

Community opinion survey

A public opinion survey was conducted to broaden community input. Data were collected by convenience sampling, as the survey was informally distributed through health and education partners and their networks. The survey, which was provided in English and Spanish, was available electronically and as an insert in a statewide youth sexual health magazine.17 Survey results represented only those who participated and could not be generalized to all Oregonians. Topics included knowledge, satisfaction, and support for comprehensive sex education and services in their community. Results from 1,733 young people and adult respondents were analyzed, summarized, and used to design strategic directions and elements of the plan.

Plan completion

Writing the plan was a collaborative effort among OYSHP members. Fifty-seven young people from four Oregon counties, 32 service providers with culturally specific knowledge, and 67 community members provided feedback regarding the final draft of the plan during an open comment period. An extensive process of editing the plan's draft language was developed. A series of OYSHP work sessions used a consensus-based review process that was designed to ensure plan integrity and increase partnership engagement. The plan was vetted through community-based partners, local and state agencies, and the Oregon Governor's Office. The final plan represented approximately three years of work and input from 5,128 Oregonians.

PLAN OVERVIEW

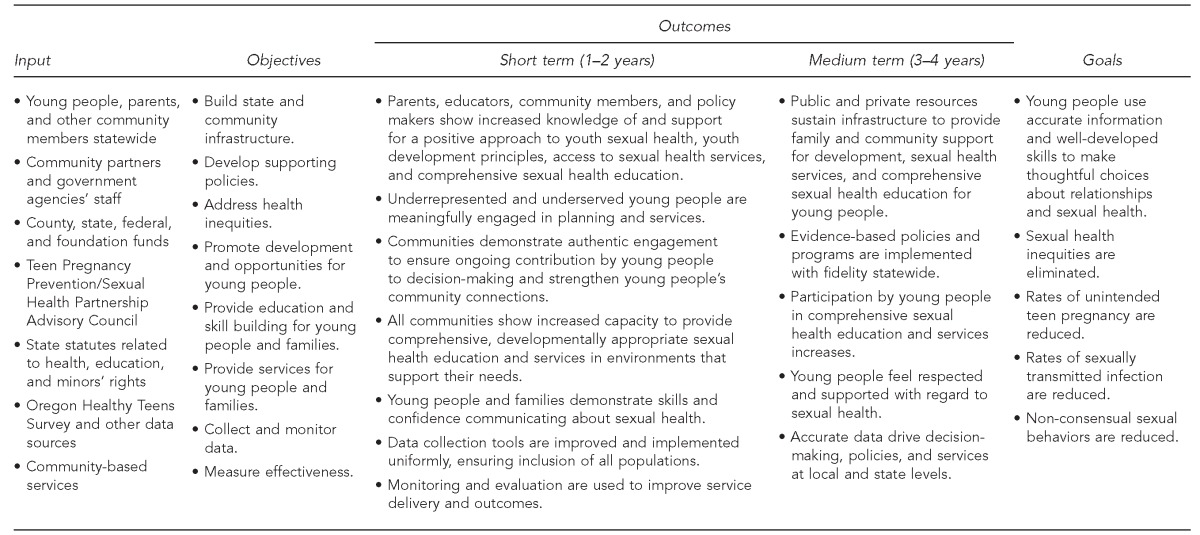

The plan is a user-friendly guide for program planning and development, policy, funding, and stakeholder education to support the sexual health of Oregon's young people. The plan includes eight objectives for state and community actions and five overarching goals designed to improve sexual health among Oregon's young people. The objectives, rather than being proscriptive, were designed to provide a framework for any group to tailor to their community. The plan includes a logic model (Figure) that can be used to map a proposed program and incorporates inputs, objectives, and outcomes that are specific to youth sexual health programming. A sample community action plan recommends strategies and activities that are essential to fulfilling the eight objectives.10 Communities and stakeholders are expected to adjust the plan to fit their needs so that planning is manageable, community-driven, and functional.

Figure.

Youth sexual health logic modela

aAdapted from: Oregon Department of Human Services, Children, Adults and Families Division. Youth sexual health plan. Salem (OR): Oregon Department of Human Services; 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/children/teens/tpp/yhsp-021109.pdf?ga=t [cited 2012 Feb 22].

Dissemination and implementation

Oregon's framework of youth sexual health promotion was widely disseminated and sent to school districts, local public health authorities, child welfare offices, school-based health centers (SBHCs), self-sufficiency offices, clinicians, and public health and social service providers. Nationally, the plan was shared with Association of Maternal and Child Health program member states, state adolescent health coordinators, rape prevention and education grantees, and CDC Division of Adolescent and School Health state contacts. OYSHP members presented the plan at conferences, meetings, and trainings of professional and community groups (e.g., police officers, librarians, and parent-teacher associations), and to state and national associations and policy makers. Presenting youth sexual health as inclusive of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being allowed groups to examine their role in the matter, even if sexual health was not primary to their mission.

Since releasing the plan, OYSHP member agencies have worked individually and collaboratively to conduct activities across the plan's eight objectives. Member agencies have completed 40 distinct activities to meet the plan's objectives; additionally, more than 100 activities influenced by the plan were completed to fulfill other program needs. Because of partner capacity and existing resources, the OYSHP made significant progress in meeting objectives regarding services and education for young people and families, youth development, health inequities, and supporting policy.

Recognizing the importance of youth-friendly5 and accessible health services, two OYSHP agencies increased clinic access. During 2009–2011, the state legislature expanded SBHC investment, opening seven new SBHCs. Oregon requires that SBHCs provide basic reproductive health services and allow direct access to clinical care for school-aged young people. Planned Parenthood of Southwestern Oregon, a partner in the OYSHP, increased clinic hours and expanded services in four underserved communities.

The first collaborative policy success after the plan's release was the passage of legislation in 2009 that updated and revised the sex education law for grades kindergarten to 12, eliminating the if/then clause contained in the previous law. All member agencies of the OYSHP provided written or oral testimony during legislative hearings. Oregon's sex education law, which is among the most comprehensive in the U.S.,18,19 requires that all school districts provide sex education that enhances students' understanding of sex as a natural and healthy part of human development.

Other collaborative successes involved funding opportunities. The OYSHP worked with organizations throughout the state to coordinate applications and made a concerted effort to ensure that applications from Oregon would be complementary rather than competitive. Applicants used the Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan to inform and support their applications for federal funding. The comprehensive sex education law was instrumental in Oregon's successful application for competitive funds. OYSHP members collaborated on a private foundation grant to support sex education in schools and were awarded a grant to fund the Working to Institutionalize Sexuality Education (WISE) Initiative during 2009. To date, WISE has supported teacher training, school health advisory council training, and engagement activities in sex education for young people in 13 Oregon school districts.

During 2010, the federal government released teen pregnancy prevention funding opportunity announcements. Five agencies in Oregon received federal teen pregnancy prevention funding. Oregon's two Planned Parenthood affiliates received funding to implement the Teen Outreach Program, an evidence-based development project that engages young people aged 13–18 years in experiential learning. The Oregon Department of Human Services received federal funding to support My Future My Choice (MFMC), an Oregon-developed comprehensive sex education program for middle school students. The Oregon Health Authority received funding to support implementation of ¡Cuídate!, a Hispanic-focused human immunodeficiency virus prevention program. During 2011, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde was awarded a Tribal Personal Responsibility Education Program teen pregnancy prevention grant.

Because of coordinated efforts guided by the OYSHP, federal teen pregnancy prevention funds and private foundation funds are being used in 21 of Oregon's 36 counties to increase community-level capacity to promote youth sexual health, provide youth sexual health programming in areas of greatest need, and address sexual health disparities among racial/ethnic groups.

The Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan emphasizes that young people should be involved in all aspects of sexual health work, from planning to program evaluation. OYSHP agencies have changed the way they work to become more focused on young people. Examples include the revision of the MFMC curriculum to include more sexual health and healthy relationship sessions led by young people; training and support of MFMC Teen Advisory Board members to become community advocates and leaders for youth sexual health concerns; the use of WISE funds to support the involvement of young people in school health advisory councils, community forums, and statewide sexual health conferences; and rape prevention education grantees receiving youth development training. The latter highlights a shift in emphasizing sexual health and promoting healthy relationships as a way to end sexual violence.

Developing the plan allowed partners to more fully understand how family, income, age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, immigration status, sexual orientation, and geography influence sexual health disparities. Working in collaboration, OYSHP agencies have increased outreach and instruction regarding sex education and health services for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning young people; participated in an action-learning collaborative on preconception care for young adults with disabilities initiated by the Association of Maternal and Child Health programs and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; secured funding to develop a Latina Health Coalition with adult and adolescent participants in southern Oregon; and commissioned research briefs on seven populations of disenfranchised young people.

The Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan has influenced the day-to-day work of Oregon agencies and more precisely defined the scope of their work, as evidenced by a memorandum of understanding among three state agencies regarding their roles and responsibility in addressing youth sexual health (available upon request). The activities by the OYSHP since the plan's release demonstrate a sustainable, committed effort by all partners to promote youth sexual health.

CONCLUSION

The Oregon Youth Sexual Health Plan represents a substantial advancement in state public policy, as did the reframing of the traditional public health problem of teen pregnancy into a positive youth development framework of sexual health. The plan will serve as a cornerstone of Oregon's future work, which can be carried forward by the OYSHP, since its establishment as a formal entity. The plan's success can be attributed to using a community-based participatory research process to engage young people and give voice to their recommendations, informing the process with an array of qualitative and quantitative data-gathering methodologies, receiving input from culturally diverse communities representing a broad spectrum of -public opinion, and leveraging the human and financial resources of a public-private collaborative to complete the work.

The process and plan will serve as a guide to comprehensively address the sexual health of young people. As Oregon's work to address youth sexual health issues develops in the coming years, the state will be able to monitor sexual health outcome and behavior indicators to show the effectiveness of a holistic approach to sexual health.

Footnotes

The authors thank the members of the Oregon Youth Sexual Health Partnership who confirmed historical detail and contributed to an assessment of plan-related activities. No Institutional Review Board determinations were required to conduct the plan's activities.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Sexual and reproductive health: gender and human rights. [cited 2012 Feb 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/sexual_health/en.

- 2.Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 2007;369:1220–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Population Fund. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development; 1995; New York: United Nations Population Fund. Report No.: A/CONF.171/13/Rev.1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haslegrave M. Implementing the ICPD Programme of Action: what a difference a decade makes. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:12–8. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Population Fund. New York: UNFPA; 2003. [cited 2012 Nov 2]. State of world population, 2003. Meeting reproductive health service needs. Also available from: URL: https://www.unfpa.org/swp/2003 /english/ch5/page3.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. Policy update: House zeros out existing abstinence-only funding; invests in evidence-based prevention efforts. 2009. [cited 2012 Mar 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.siecus.com/index .cfm?fuseaction=Feature.showFeature&featureID=1786.

- 7.Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. New York: SIECUS; 2010. [cited 2012 Mar 20]. In brief: federal funding streams for teen pregnancy prevention, sex education, and abstinence-only programs. Also available from: URL: http://www.siecus.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=page.viewpage&pageid=1350. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guide to Community Preventive Services. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Community Preventive Services Task Force; 2009. [cited 2012 Mar 28]. Prevention of HIV/AIDS, other STIs and pregnancy: group-based abstinence education interventions for adolescents. Also available from: URL: http://www.thecommunityguide .org/hiv/abstinence_ed.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haffner DW. New York: Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States; 1995. [cited 2012 Mar 10]. Facing facts: sexual health for America's adolescents. Also available from: URL: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/search/detailmini.jsp?_nfpb=true&_&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=ED391779&ERICE xtSearch_SearchType_0=no&accno=ED391779. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oregon Department of Human Services, Children, Adult and Families Division. Salem (OR): Oregon Department of Human Services; 2009. [cited 2012 Feb 22]. Youth sexual health plan. Also available from: URL: http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/children/teens/tpp/yhsp-021109.pdf?ga=t. [Google Scholar]

- 11. OR Rev. Stat. § 336.455 (2009)

- 12. OR Rev. Stat. § 109.610 (1977)

- 13. OR Rev. Stat. § 109.640 (2010)

- 14.Resnick MD. Protective factors, resiliency, and healthy youth development. Adolesc Med. 2000;11:157–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oregon Department of Human Services, Children, Adult and Families Division. Salem (OR): Oregon Department of Human Services; 2009. [cited 2012 Jul 17]. Oregon youth sexual health plan appendices. Also available from: URL: http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/children /teens/tpp/resources-bw-012609.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Healthy Teens Survey 2007. [cited 2012 Nov 1]. Available from: URL: https://public.health.oregon.gov/BirthDeathCertificates/Surveys/OregonHealthyTeens/results/2007/Pages/index.aspx.

- 17.Oregon Department of Human Services, Oregon Teen Pregnancy Task Force. Portland (OR): Oregon Department of Human Services; 2006. [cited 2012 Feb 22]. The rational enquirer. Also available from: URL: http://public.health.oregon.gov/HealthyPeopleFamilies/Youth/Documents/RE/2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Advocates for Youth. Sex education resource center. [cited 2012 Feb 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org /index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1039&Itemid=629.

- 19.Guttmacher Institute. State policies in brief: sex and HIV education. [cited 2012 Oct 31]. Available from: URL: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SE.pdf.