Abstract

PURPOSE

Prevalence rates, and bivariate comorbidity patterns, of many common mental disorders differ significantly across ethnic groups. While studies have examined multivariate comorbidity patterns by gender and age, no studies to our knowledge have examined such patterns by ethnicity. Such an investigation could aid in understanding the nature of ethnicity-related health disparities in mental health and is timely given the likely implementation of multivariate comorbidity structures (i.e., internalizing and externalizing) to frame key parts of DSM-5.

METHODS

We investigated whether multivariate comorbidity of 11 common mental disorders, and their associated latent comorbidity factors, differed across five ethnic groups in a large, nationally representative sample (N = 43,093). We conducted confirmatory factor analyses and factorial invariance analyses in White (n = 24,507), Hispanic/Latino (n = 8,308), Black (n = 8,245), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 1,332), and American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 701) individuals.

RESULTS

Results supported a two-factor internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor model in both lifetime and 12-month diagnoses. This structure was invariant across ethnicity, but factor means differed significantly across ethnic groups.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings, taken together, indicated that observed prevalence rate differences between ethnic groups reflect ethnic differences in latent internalizing and externalizing factor means. We discuss implications for classification (DSM-5 and ICD-11 meta-structure), health disparities research, and treatment.

Keywords: comorbidity, ethnicity, internalizing, externalizing, prevalence, disparities

Ethnicity and Mental Disorder Prevalence Rates

Epidemiological studies of psychopathology in the United States have demonstrated that prevalence rates of many common mental disorders differ across ethnic groups. Consider the results from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and its subsequent replication (NCS-R), which indicated that lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of major depressive disorder differed significantly by ethnicity [1-3]. Similarly, findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)—the largest epidemiological study of psychopathology conducted in the United States—highlighted ethnicity differences in the prevalence rates of mood, anxiety, alcohol use, drug use, and personality disorders [4-6]. For instance, although 8.5% of the total NESARC sample reported experiencing an alcohol use disorder in the previous year, the prevalence rates differed markedly across ethnic groups: 4.5% of Asian/Pacific Islander, 6.9% of Black, 7.9% of Hispanic/Latino, 8.9% of White, and 12.1% of American Indian/Alaska Native individuals met criteria for a past-year alcohol use disorder [5].

Such findings regarding major psychiatric disorders present an epidemiological paradox. For instance, Black Americans in the U.S. face discrimination that exposes them to disadvantaged socio-economic status, worse living conditions, and greater stress and adversity due to marginalized social status compared to Whites [7-11]. Stress theory and general population findings indicate that these circumstances are general risk factors for common psychiatric disorders [12-14]; however, epidemiologic studies consistently document lower rates of psychiatric disorders among non-Hispanic Black Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites [2, 3, 7, 11, 15-18].

Taken together, there is substantial ethnic patterning of psychiatric disorders in the United States, but these patterns do not necessarily correspond to theories regarding stress and social status. This suggests a complex interplay of factors that promote risk for psychiatric disorders at the population level for different ethnic subgroups. Such results underscore the need for a better understanding of ethnicity-related health disparities in mental disorder prevalence rates.

Ethnicity and Comorbidity

It is not only prevalence rates that differ across ethnic groups; bivariate comorbidity also differs by ethnicity. For instance, one study using the NESARC data reported markedly different comorbidity patterns of 12-month mood, anxiety, personality, alcohol use, and drug use disorders [5]. Those investigators found the odds ratio for having a mood disorder was 4.9 if individuals had a drug use disorder, without stratifying by ethnicity. The association between mood and drug use disorders varied notably by ethnicity, however: Asian/Pacific Islander (OR = 3.2), White (4.1), Hispanic/Latino (5.4), Black (7.1), and American Indian/Alaska Native (10.0). As another example, in the total sample, the odds ratio for having a personality disorder if individuals had an alcohol use disorder was 2.6. This association also varied widely by ethnicity: White (2.3), American Indian/Alaska Native (2.5), Black (2.8), Hispanic/Latino (3.7), and Asian/Pacific Islander (7.2). Similar results were seen for anxiety disorders. Thus, while having an alcohol or drug use disorder was related to increased risk for mood, anxiety, and personality psychopathology, the magnitude of this risk increase was related to ethnicity, a relationship unlikely to be accounted for by race/ethnic differences in reliability since such differences have not been found [19, 20]. Of note, such ethnicity-related comorbidity differences appear to manifest across a wide range of possible disorder pairings and cut across Axes I and II. Findings such as these suggest that ethnicity is associated not only with risk to experience individual mental disorders but also with how mental disorders tend to co-occur.

Latent Comorbidity Factors

The origins and meaning of ethnicity differences in prevalence rates and bivariate comorbidity patterns are important issues, because they may provide important clues about etiology and inform public health initiatives. A deeper understanding of these differences may emerge by modeling multivariate comorbidity explicitly. Multivariate comorbidity can be conceptualized as a manifestation of underlying structures of mental disorders. Previous research has determined that these structures are best characterized as latent dimensional factors (rather than latent classes or class-dimension hybrids [21-23]) that reflect comorbidity patterns. In such a model, prevalence rates and comorbidity of categorical disorders are conceptualized as representing a level on one or more dimensional latent factors, which ranges from very low to very high. The diagnostic variance for disorder X is conceptualized as the sum of (a) the variance a particular disorder shares with other disorders (e.g., the variance common to major depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder) and (b) the disorder-specific variance that is unique to a particular disorder (e.g., the unshared variance that makes major depression different from other disorders).

Ethnicity differences in these factors could account for observed ethnicity differences in prevalence rates and comorbidity. For instance, it could theoretically be the case that all mental disorders in one ethnic group tend to co-occur and that individual disorders reflect a single “psychopathology and comorbidity” factor. In another ethnic group, relatively uncorrelated mood, anxiety, and substance use latent factors might manifest as “pockets” of comorbidity, where mood disorders tended to co-occur with each other independent of other disorders, and the same would be true for anxiety and for substance use disorders. These potential differences in the structure of underlying factors of psychopathology may aid in explaining paradoxical findings. Given the univariate ethnicity differences in prevalence rates, and bivariate differences in comorbidity across ethnic groups, investigation of these structures of multivariate comorbidity seems particularly worthwhile.

While it is possible that different underlying structures exist in each ethnic group, it is also possible that a single structure of common mental disorders may exist across ethnicities, with observed prevalence rate differences reflecting different average standings on latent comorbidity factors. For example, (1) underlying mood/anxiety and antisocial behavior/substance use factors may account for disorder comorbidity patterns, and (2) different average levels of these factors across ethnic groups would manifest as different observed prevalence rates of disorders in each ethnicity. This is a question of factorial invariance: Is the latent structure of common mental disorders invariant across ethnicity? If so, observed prevalence rate differences between ethnicities could be inferred to arise from different average standings on the factors across ethnic groups, making them key constructs for public health efforts.

Numerous studies examining the latent structure of common mental disorders have generally agreed upon a two-factor structure involving internalizing and externalizing comorbidity factors [for a recent review of this literature, see 24]. The internalizing factor, which comprises emotion-based disorders of distress and fear, is associated with major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder; trait neuroticism also relates to these disorders [25, 26]. The externalizing factor is associated with antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorders, and trait disinhibition [27-32].

The internalizing-externalizing structure has emerged in data from a diverse set of countries spanning six continents [28, 31-35], suggesting an ethnicity-invariant latent comorbidity structure, given the diverse ethnic composition of these samples. However, factorial invariance analyses are necessary to evaluate formally the similarity of comorbidity structures in different ethnic groups. No studies known to us examined, in a factorial invariance framework, whether the underlying comorbidity structure of psychopathology differs by ethnicity. This dearth of ethnicity-related research stands in marked contrast to recent research on other individual differences, which has demonstrated that latent disorder comorbidity factors are generally invariant across gender and the lifespan [36-38].

Determining whether latent comorbidity factors differ by ethnicity is a critical issue in psychiatric classification and research, given recent focus on these constructs. For example, it appears likely that the internalizing and externalizing factors may be used to frame the “meta-structure” of mental disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-11 [39, 40]. Further, recent research has indicated that internalizing and externalizing factors have more than descriptive utility. These factors have been shown to account for the continuity and development of comorbidity over time [33] as well as the links between disorders and future important health outcomes such as suicide attempts [21, 41]. Behavior genetic research has also demonstrated these factors largely represent genetic effects on many Axis I and II disorders [42-44]. Unfortunately, it is currently unknown whether the apparent utility of internalizing and externalizing for improving nosology and understanding etiology is impacted by ethnicity. Given that prevalence rates and bivariate comorbidity patterns differ by ethnicity, multivariate invariance cannot simply be assumed, and formal evaluation is necessary.

The Current Study

The current study was conducted to fill this gap in the literature by examining the structure of common mental disorders across five ethnicities in the nationally representative NESARC sample (N = 43,093). We had two primary aims: (1) to determine the structures of common mental disorder comorbidity separately in White, Hispanic/Latino, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, and (2) to test whether the emergent structures were invariant across ethnicities. Additionally, we investigated ethnicity differences in the average standing on latent factor levels and considered these differences in light of previously reported ethnicity prevalence rate differences.

Method

Participants

We analyzed data from 43,093 individuals who participated in the NESARC (2001-2002). The design of the NESARC has been described previously [45]. The NESARC is a representative sample of the civilian, non-institutionalized United States population at least 18 years of age. Hispanic/Latino, Black, and young adults were oversampled. Women composed 57% (n = 24,575) of the sample; the age range was 18-98 years. Race/ethnicity was selected by participants and defined via Census Bureau algorithms into: non-Hispanic/Latino White (“White” hereafter for brevity; 56.9%; n = 24,507), Hispanic or Latino (“Hispanic;” 19.3%; n = 8,308), non-Hispanic/Latino Black (“Black;” 19.1%; n = 8,245), non-Hispanic/Latino Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (“Asian/Pacific Islander;” 3.1%; n = 1,332), and non-Hispanic/Latino American Indian/Alaska Native (“American Indian/Alaska Native;” 1.6%; n = 701). The NESARC was weighted to be representative of the age, sex, and racial/ethnic distribution of the United States based on the 2000 census. The research protocol, including informed consent, received full ethical review and approval and all participants gave informed consent prior to participation.

Assessment

Lifetime and 12-month DSM-IV diagnoses were made using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) [46, 47], a structured interview designed for administration by experienced lay interviewers. We examined major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, marijuana dependence, other drug dependence, and antisocial personality disorder AUDADIS-IV diagnoses. This list represented all disorders assessed in the NESARC that had their positions in the internalizing-externalizing structure clearly established by previous research. We calculated the other drug dependence variable by collapsing relatively uncommon forms of drug dependence (i.e., stimulants, opioids, sedatives, tranquilizers, cocaine, solvents, hallucinogens, heroin, and any other drug not assessed) into one variable with sufficient variance for structural modeling. In keeping with the DSM-IV conceptualization of personality disorders as lifelong, antisocial personality disorder was assessed only as a lifetime diagnosis, which we used in both lifetime and 12-month analyses. AUDADIS-IV has diagnostic reliabilities that are generally good to excellent (e.g., kappas = .42 to .84) [18]; test-retest estimates similar to other structured interviews, such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) and the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview [48]; and advantages over interviews, including the DIS, such as assessment of clinically significant distress and impairment after syndrome characterization [18].

Statistical Analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted in Mplus version 6 [49] using the default delta parameterization and a weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator, which allowed us to treat diagnoses as categorical and to use the NESARC’s weighting, clustering, and stratification variables in all analyses. Fit indices considered were the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA); the number of free parameters in the model was also used. Chi-square goodness-of-fit and difference tests were not employed, as they are sensitive to large sample sizes; other fit indices, such as AIC and BIC, are not available with the WLSMV estimator. CFI/TLI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values less than .06 suggest reasonably good model fit [50], and the TLI can exceed 1.00 in cases of very good fit. Simulation studies of common fit indices lead investigators to propose a CFI difference critical value of .01 be used in factorial invariance research to determine whether the addition of constraints leads to notably worse model fit [51]. Finally, the number of free parameters is the number of parameters that were freely estimated in the model. As the number of free parameters decreases, model parsimony increases.

Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (i.e., where all five ethnicities were modeled simultaneously but as separate groups) allows for the comparison of the average factor levels of each group. A particular group’s factor mean is used as a reference to estimate the factor means of the other groups. In this case, White individuals were chosen as the reference group, due to this group being the largest ethnicity sub-sample. White individuals’ internalizing and externalizing factor levels were thus fixed to zero. The factor means in the other ethnic groups could then be estimated as deviation scores from those of the White ethnic group. Because the variances of the latent factors were fixed to unity, these deviation means can be interpreted as z-scores.

Results

Analyses by Ethnicity

In keeping with the literature (and supported by exploratory factor analyses not reported here for the sake of brevity), we tested the fit of the two-factor internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor model in each ethnic group. Major depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia were parameterized to load on an internalizing factor, while antisocial personality disorder and alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, and other drug dependence loaded on an externalizing factor. As reported in Table 1, the two-factor model fit quite well. In all five ethnicities, using both lifetime and 12-month diagnoses, every fit index ranged from good to excellent; no fit index fell below threshold for acceptable fit. These results indicated that the internalizing-externalizing factor model is a well fitting model of disorder multivariate comorbidity structure in all ethnicities and for both lifetime and 12-month diagnoses.

Table 1.

Model fit statistics

| CFI | TLI | RMSEA | # Free | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 24,507) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | .98 | .98 | .01 | -- |

| 12-month diagnoses | .98 | .97 | .01 | -- |

| Hispanic (n = 8,308) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | .99 | .98 | .01 | -- |

| 12-month diagnoses | .97 | .97 | .01 | -- |

| Black (n = 8,245) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | .98 | .97 | .01 | -- |

| 12-month diagnoses | .98 | .97 | .01 | -- |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 1,332) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | .99 | .99 | < .01 | -- |

| 12-month diagnoses | .99 | .99 | < .01 | -- |

| American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 701) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | 1.00 | 1.00 | < .01 | -- |

| 12-month diagnoses | .96 | .95 | < .01 | -- |

| Multigroup (All ethnicities) | ||||

| Lifetime diagnoses | ||||

| Unconstrained model | .98 | .98 | .02 | 115 |

| Constrained model | .99 | .99 | .01 | 75 |

| 12-month diagnoses | ||||

| Unconstrained model | .97 | .97 | .01 | 115 |

| Constrained model | .98 | .98 | .01 | 75 |

Note: Multigroup modeled ethnicities simultaneously. The unconstrained model allowed each ethnicity to have unique factor loadings and thresholds; the constrained (invariant) model constrained factor loadings and thresholds to equality across ethnicities. CFI: comparative fit index. TLI: Tucker-Lewis index. RMSEA: root mean squared error of approximation. # Free: number of parameters freely estimated in the model. See text for full description of the ethnic groups.

Invariance

Because putatively similar internalizing-externalizing models fit the data well in each ethnic group, we next sought to determine whether the same internalizing-externalizing model— that is, with identical factor loadings and indicator thresholds—could be used in all the ethnicities. This is a question of factorial invariance: Does the latent comorbidity structure of these disorders vary across ethnicity, or can a single model function well to conceptualize comorbidity in every ethnicity? To determine the potential ethnicity invariance of the internalizing-externalizing factor model, we conducted two (for lifetime and 12-month diagnoses) multigroup confirmatory factor analyses, wherein we modeled the disorders’ structure in each ethnicity simultaneously. Our approach was to test ethnicity invariance by freeing or constraining factor loadings and indicator thresholds in tandem across the ethnic groups, which resulted in the comparison of two models: (1) the unconstrained model, where loadings and indicator thresholds were uniquely estimated in each ethnicity, factor means were set to zero in all ethnicities, and scaling factors were fixed to one in all ethnicities, and (2) the constrained model, where loadings and indicator thresholds were constrained to equality across ethnicities and factor means and scaling factors were freely estimated, except in White individuals, where they were fixed to zero and one, respectively. If the unconstrained model were superior, the factors would represent different constructs, indicating that mean factor levels cannot be compared meaningfully across ethnicities. If the more parsimonious constrained model were superior, this would indicate a single, invariant latent comorbidity structure of common mental disorders that did not change across ethnic groups. Further, ethnicity invariance would indicate that observed prevalence rate ethnicity differences emerge from different average standings on the latent internalizing and externalizing factors in each ethnic group.

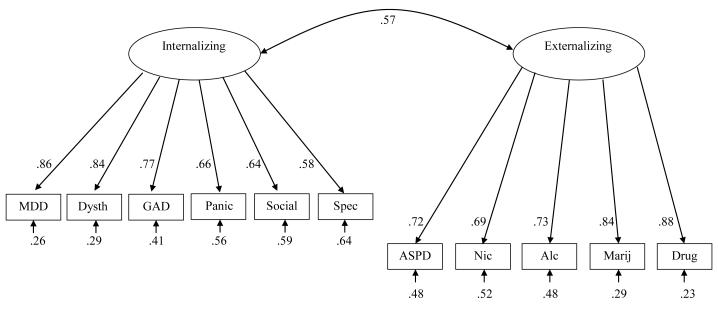

As reported in Table 1, for lifetime diagnoses, the unconstrained multigroup model fit worse on all fit indices than did the more parsimonious constrained model. For 12-month diagnoses, the unconstrained model fit the same or slightly worse on each fit index than did the more parsimonious constrained model. The .01 critical difference in CFI values [51] was not reached when constraints were placed on the model; indeed, the CFI values improved with the addition of model constraints. These results indicated that, for both lifetime and 12-month diagnoses, the latent internalizing-externalizing factor model of common mental disorders was invariant across the ethnicities. The constrained lifetime model, with standardized parameters from the White individual sample, is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The constrained (ethnicity invariant) model in White, Hispanic, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals using lifetime diagnoses.

Note. Values are standardized and all significant (p < .001). For clarity, only estimates for White individuals’ lifetime diagnoses are presented; values for Hispanic, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals differed only slightly due to standardization. MDD: major depressive disorder. Dysth: dysthymic disorder. GAD: generalized anxiety disorder. Panic: panic disorder. Social: social phobia. Spec: specific phobia. ASPD: antisocial personality disorder. Nic: nicotine dependence. Alc: alcohol dependence. Marij: marijuana dependence. Drug: other drug dependence. Short arrows with numbers indicate measurement errors.

See text for full description of the ethnic groups.

Factor Means

Because the internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor model was invariant across the five ethnicities, it was informative to examine the latent means of the internalizing and externalizing factors in each group. These factor means indicated how the ethnic groups differed in their average levels on internalizing and externalizing factors; it would be these latent mean differences that accounted for the observed ethnicity differences in prevalence rates. The internalizing and externalizing means among White individuals were both fixed to zero and served as a reference metric for the means of the other ethnic groups. Table 2 details the standardized means (as deviation scores from the White reference group) and significant (p < .05) differences between ethnic groups. Given the ethnicity invariant structure, we can infer these ethnicity differences in latent internalizing and externalizing factor levels gave rise to the ethnicity prevalence rate differences previously reported in the NESARC [4-6].

Table 2.

Factor means by ethnicity

| Lifetime Diagnoses | 12-month Diagnoses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | EXT | INT | EXT | |

| Hispanic | −.28A,N,W | −.33N,W | −.15N | −.21N |

| Black | −.24A,N,W | −.35N,W | −.07N | −.13N |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −.51B,H,N,W | −.35N,W | −.39N,W | −.09N |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | .31A,B,H,W | .51A,B,H,W | .22A,B,H,W | .60A,B,H,W |

Note: Internalizing. EXT: Externalizing. Factor means are given in standard deviation units from reference group (i.e., means in White individuals were fixed to zero). Higher scores represent higher mean factor levels. Superscript letters indicate a constrained model factor mean differs (p < .05) from that of

Asian/Pacific Islander,

Black,

Hispanic,

American Indian/Alaska Native, or

White individuals.

See text for full description of the ethnic groups.

Discussion

Aim 1: Structures of Common Mental Disorders Across Ethnicity

Our first aim was to investigate the structures of common mental disorders in White, Hispanic, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals in the NESARC. Using both lifetime and 12-month diagnoses, a two-factor internalizing-externalizing comorbidity structure fit multivariate patterns of comorbidity well in all five ethnicities. These findings suggested the presence of a common latent structure.

Aim 2: Ethnicity Invariance of Latent Comorbidity Factors

Our second aim was to examine the potential invariance of the structure of common mental disorders across ethnic groups. We conducted multigroup factorial invariance analyses of the internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor model. Our results suggested that the same structure (e.g., identical factor loadings and indicator thresholds) functioned well in all five ethnic groups, indicating that the internalizing-externalizing factor model can serve as a generalizable model of multivariate comorbidity.

Implications

Classification

Our results are congruent with calls for reorganization of the DSM-5 and ICD-11 to reflect an internalizing-externalizing meta-structure for many common disorders. A growing body of research supports an organization that would move away from the current, rationally-derived disorder groups, such as “mood disorders” and “anxiety disorders,” which imply a boundary between the highly comorbid disorders these groupings subsume. Instead, the data suggest that the mood and anxiety disorders can be well characterized by a model that groups them together under an “internalizing disorder” heading. A similar “externalizing disorders” grouping could include disorders related to substance use, antisociality, and impulsivity. Such groupings are more reflective of empirical findings and do not reify disorder groupings of putatively similar disorders (e.g., “mood disorders”), and divisions between putatively dissimilar but highly comorbid disorders, that are not supported by the data.

The establishment of between-group invariance is critical to any efforts to implement such a classification system in a future nosology. For instance, if the internalizing-externalizing model were present in only some population sub-groups, or if its factors represented statistically different constructs across groups, its generalizability and utility as a classification meta-structure would be limited. There have previously been indications that the internalizing-externalizing structure is invariant across gender [36, 38], and that internalizing is largely invariant across the lifespan [37]. The current study contributed a critical missing piece to the evaluation of this meta-structure: ethnicity invariance.

Our results suggest that the use of internalizing and externalizing disorder groupings would produce no ethnicity bias if classification systems were to adopt them as a means to organize many common mental disorders. The analyses within each ethnic group supported the presence of an internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor structure. The ethnicity invariance indicated that these structures were statistically equivalent, such that the factors represented the same latent constructs across groups. Taken together, these findings support the position that an internalizing-externalizing meta-structure would perform well across ethnic groups.

Finally, this study’s results are congruent with recent moves toward dimensional definitions for many disorders. Our findings highlight how putatively categorical disorders, and their comorbidity patterns, reflect a dichotomization of underlying dimensions (factors) of psychopathology. In other words, the fundamental latent structures of comorbidity appear to be dimensional in nature. While converting these dimensions into categories through application of diagnostic thresholds may have some utility, it is important not to define psychopathology as representing solely a group of categorical disorder entities.

Ethnicity differences in disorder prevalence

As the internalizing-externalizing comorbidity factor model was invariant across ethnicity, we can infer that observed prevalence rate ethnicity differences in categorical diagnoses of many common disorders reflect ethnicity differences in latent dimensional comorbidity levels. This finding supports latent factors as major targets of inquiry for investigations of ethnicity differences in psychopathology. We believe it is no longer sufficient to ask solely whether and why ethnic groups (or likely any groups of individuals) differ on discrete categorical disorders. Instead, research could benefit from investigation of whether and why the unifying dimensional latent factors differ across groups. For instance, adverse childhood events such as abuse and neglect are associated with increased factor levels in adulthood [52]. Investigations of particular categorical disorders, while valuable, do not capture the broader, generalizable themes that latent factors represent.

Further, these results could be utilized in future research to begin to explain paradoxical findings in the epidemiological literature. For example, some have hypothesized that one reason that Black Americans have lower rates of major depression than White Americans, despite a greater concentration of risk factors, is that the DSM-IV diagnosis does not adequately capture the experience of depression in this population [9, 53-55]. In fact, Black individuals report lower levels of well-being, higher levels of distress, and higher depressive scores when assessed on non-DSM instruments [53, 56]. Examining risk factors for psychopathology across latent factors could more meaningfully characterize the experience of psychopathology across ethnic subgroups and attenuate diagnostic bias.

Treatment

Our results are congruent with findings that many disorders respond to the same treatment modalities. For instance, symptoms of anxiety and depression often improve with pharmacological interventions such as tricyclics, SSRIs, and newer antidepressants [57]. As such, it appears that pharmacological interventions may target the core of internalizing and externalizing rather than particular disorders [58]. Similarly, several psychotherapy modalities are empirically supported for treatment of both mood and anxiety disorders [59]. This effectiveness of single treatments to target multiple disorders has prompted some researchers to propose transdiagnostic treatment approaches [60]. A primary rationale of such approaches is that internalizing and externalizing are common factors underlying variance in multiple, putatively distinct DSM-IV disorders. Our findings support the applicability, across ethnic groups, of such treatment protocols based on these latent factors.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. First, NESARC diagnostic interviews were administered by extensively trained lay interviewers rather than clinicians. This limitation is mitigated somewhat by the AUDADIS-IV’s structured design and generally good psychometric properties. Second, lifetime prevalence rates based on retrospective reporting can be biased, but our results for 12-month diagnoses, which required relatively comparatively less retrospection, were consistent with those for lifetime diagnoses. Third, the results of structural modeling studies such as this one reflect the variables included in the analysis. As such, inclusion of additional disorders could potentially alter findings, and the generalizability of these findings to disorders not included (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder) is unclear. These would be worthwhile topics for further research. Fourth, our results focused on United States data alone, and testing cross-national and cross-cultural invariance would be worthwhile. Finally, the current study addressed diagnostic comorbidity and thus analyzed DSM-IV diagnoses. Future studies would benefit from also examining symptom-level data [61], which addresses a somewhat different topic.

Acknowledgements

U01AA018111, R01DA018652, and K05AA014223 (Hasin). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and funded, in part, by the Intramural Program, NIAAA, National Institutes of Health, with additional support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None.

Contributor Information

Nicholas R. Eaton, Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794.

Katherine M. Keyes, 1051 Riverside Drive #123, New York, NY 10032.

Robert F. Krueger, 75 East River Road, Minneapolis, MN 55455.

Arjen Noordhof, Dept. of Psychology, Weesperplein 4, 1018 XA Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Andrew E. Skodol, 6102 N. 28th Street, Phoenix, AZ 85016.

Kristian E. Markon, The University of Iowa, Seashore Hall, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Bridget F. Grant, NIH/NIAAA, LEB, 5635 Fishers Lane, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Deborah S. Hasin, 1051 Riverside Drive #123, New York, NY 10032.

References

- 1.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang B, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Race-ethnicity and the prevalence and co-occurrence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, alcohol and drug use disorders and Axis I and II disorders: United States, 2001 to 2002. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith SM, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein R, Huang B, Grant BF. Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:987–998. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger N. Discrimination and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 36–75. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(1):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:173–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR. Racial variations in adult health status: Patterns, paradoxes, and rospects. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 371–409. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alchol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horton J, Compton W, Cottler LB. Reliability of substance use disorder diagnoses among African-Americans and Caucasians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;57:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, Hasin DS, Grant BF. The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0029598. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walton KE, Ormel J, Krueger RF. The dimensional nature of externalizing behaviors in adolescence: Evidence from a direct comparison of categorical, dimensional, and hybrid models. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39:553–561. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright AGC, Krueger RF, Hobbs MJ, Markon KE, Eaton NR, Slade T. The structure of psychopathology: toward an expanded quantitative empirical model. J Abnorm Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0030133. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eaton NR, South SC, Krueger RF. The meaning of comorbidity among common mental disorders. In: Millon T, Krueger R, Simonsen E, editors. Contemporary directions in psychopathology: Scientific foundations of the DSM-V and ICD-11. Guilford Publications; New York: 2010. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lawton JM. The relationships between neuroticism and depressive symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1986;24:275–281. doi: 10.1007/BF01788029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, Sutton JM. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1125–1136. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;108:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slade T, Watson D. The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vollebergh WAM, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, et al. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krueger RF, Chentsova-Dutton YE, Markon KE, Goldberg D, Ormel J. A cross-cultural study of the structure of comorbidity among common psychopathological syndromes in the general health care setting. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):437–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Røysamb E, Kendler KS, Tambs K, Ørstavik RE, Neale MC, Aggen SH, Torgersen S, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The joint structure of DSM-IV axis I and axis II disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:198–209. doi: 10.1037/a0021660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, Grant BF, Hasin DS. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: Evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(1):282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Oltmanns TF. Aging and the structure and long-term stability of the internalizing spectrum of personality and psychopathology. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(4):987–993. doi: 10.1037/a0024406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer MD, Krueger RF, Hicks BM. Internalizing and externalizing liability factors account for gender differences in the prevalence of common psychopathological syndromes. Psychol Med. 2008;38:51–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews G, Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Carpenter WT, Jr., Hyman SE, Sachdev P, Pine DS. Exploring the feasibility of a meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11: Could it improve utility and validity? Psychol Med. 2009;39:1993–2000. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ, editors. The conceptual evolution of DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Arlington, VA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slade T. The descriptive epidemiology of internalizing and externalizing psychiatric dimensions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:554–560. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, Røysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM-IV axis I and all axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:29–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, Rathouz PJ. Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:181–189. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Introduction to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29(2):74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wittchen H-U. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th edn Author; Los Angeles: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin K, Wall MM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Childhood adversities and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):107–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown T. Critical race theory speaks to the sociology of mental health: Mental health problems produced by racial stratification. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):292–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kendrick L, Anderson NLR, Benjamin M. Perceptions of depression among young African American men. Family and Community Health. 2007;30(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mabry JB, Kiecold KJ. Anger in black and white: Race, alienation, and anger. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(1):85–101. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldberg D, Simms LJ, Gater R, Krueger RF. Integration of dimensional spectra for depression and anxiety into categorical diagnoses for general medical practice. In: Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ, editors. The conceptual evolution of DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Arlington, VA: 2011. pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam J, Shelton R, Schalet B. Personality change during depression treatment: A placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nathan PE, Gorman JM. A guide to treatments that work. 3rd edn Oxford University Press, Inc.; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Markon KE. Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom-level analysis of Axis I and II disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:273–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]