Abstract

Background

Cancer often has a profound and enduring impact on sexuality, affecting both patients and their partners. Most healthcare professionals in cancer and palliative care are struggling to address intimate issues with the patients in their care.

Methods

Study 1: An Australian study using semi-structured interviews and documentary data analysis.

Study 2: Building on this Australian study, using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, data were collected in the Netherlands through interviewing 15 cancer patients, 13 partners and 20 healthcare professionals working in cancer and palliative care. The hermeneutic analysis was supported by ATLAS.ti and enhanced by peer debriefing and expert consultation.

Results

For patients and partners a person-oriented approach is a prerequisite for discussing the whole of their experience regarding the impact of cancer treatment on their sexuality and intimacy. Not all healthcare professionals are willing or capable of adopting such a person-oriented approach.

Conclusion

A complementary team approach, with clearly defined roles for different team members and clear referral pathways, is required to enhance communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care. This approach, that includes the acknowledgement of the importance of patients' and partners' sexuality and intimacy by all team members, is captured in the Stepped Skills model that was developed as an outcome of the Dutch study.

Keywords: Sexuality, intimacy, cancer care, palliative care, communication, hermeneutics, Stepped Skills

What this study adds:

This study offers a unique combination of transcontinental findings from two studies, resulting in mutual validation of research findings and a solid base for a way forward in health care practice

This study offers an exploration of patients', partners' and professionals' perceptions regarding communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care

The Dutch study, which was informed by the Australian study, resulted in a novel team approach (Stepped Skills) to enhance communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care

Background

Cancer and its treatment can profoundly affect a person's sexual well-being, as has been increasingly acknowledged throughout the literature in the past decade. The impact is on both physical and psychological aspects of the intimate world for not only the person with cancer but (if applicable) also their partner.1-4 A person's sexuality can be compromised irrespective of cancer location or type of cancer treatment.4-6 Estimates of sexual dysfunction after cancer treatment vary from 40% to 100 % across the range of cancers.7

This article builds on the original work of Hordern and Street8-11 and a later study by De Vocht, Notter and Van de Wiel.12 The first study explored constructions of sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer and palliative care, from the patient and health professional perspective. These authors asserted that patient sexuality and intimacy was largely medicalised so that discussions remained at the level of patient fertility, contraception, and erectile and menopausal status. In contrast, patients were concerned about how to live with the intimate and sexual ramifications of their cancer diagnosis and treatment, searching for a patient-centred, and reflexive style of communication from a health professional of their choice, at a time and in a manner that best suited their individual needs. The second study was informed by the work of Hordern and Street and sought, by using in-depth interviews, to expand the understanding of patient experiences and preferences and health professional perspectives regarding communication about the impact of cancer on sexuality and intimacy, while also considering the experiences and preferences of partners.12 The current authors jointly emphasise the importance and the ‘around-the-globe’ relevance of the conclusions of this article.

Defining sexuality

‘Sexuality’ is an elusive concept to grasp. Many definitions of sexuality have been offered, for example by the World Health Organization.13 For the purpose of this paper, based on the holistic perspective of Woods14, sexuality is defined as a multidimensional concept, encompassing sexual self concept, sexual functioning and sexual relationships, a definition that was recently further differentiated in a Neo Theoretical Framework of Sexuality.2 A key point is that the concept of sexuality includes intimacy and should not be narrowed down to sexual function or sexual intercourse.5,15-17 This definition explicitly includes single people and is not to imply that sexuality and intimacy can only be experienced with a partner.

Healthcare professionals' reluctance to discuss sexuality

Healthcare professionals working in cancer and palliative care remain reluctant to raise intimate topics with patients and their partners after a cancer diagnosis,18,19 despite growing acknowledgement of and focus on patient sexuality in cancer and palliative care literature. As a result, health professionals rarely anticipate changes and potential problems regarding sexual aspects nor do they discuss these problems with patients, their partners or their colleagues when they arise.20,21 This is regrettable, as it means that often patients and their partners are struggling in silence with these changes and problems, without the validation and normalisation that many people experience these challenges, and without the expertise and strategies to assist them to move forward.22

Many reasons have been suggested for the reluctance of healthcare professionals to discuss patient sexuality and intimacy issues in the clinical setting.8-10,17,23-30 Hordern and Street explored patient and health professional communication through the lens of reflexivity, which enabled them to critically examine structures, ideas and rules that traditionally underpin everyday communication processes in clinical settings, and the contrasting expectations of patients who are increasingly armed with information downloaded from the internet, seeking second opinions and wishing to be involved in decision making. The majority of health professionals within this study did not consider patients as sexual beings, avoided the topic, felt vulnerable discussing such a sensitive topic, and only the occasional health professional took the risk of raising the topic or communicating with the patient about sexuality in a patient-centred manner. Perhaps the most poignant message, put forward by Hordern and Street,9 is that the majority of healthcare professionals (coming from a range of disciplinary backgrounds) employ a medicalised approach to all forms of communication, assuming that their clients' main concern is to fight the cancer, with some of them consciously avoiding any discussion expanding beyond medical-based communication. These authors argue that the medicalised structures within the health system perpetuate this level of communication so that the majority of patient and clinician dialogue is located at the level of diagnosis, treating and fixing the medical problem, leaving little room for the patient or health professional to explore how patients will learn to adjust and adapt to the long-term side effects of cancer treatment and the impact of this on intimate aspects of the person's life. Professionals who reflected on the why and how of their communication about intimate issues with patients recognised the relationship between being able to discuss sexual issues with patients and their own life, or their lack of life experiences regarding sexuality.9 Professionals try to avoid ‘risky’ exchanges and display a fear of being misinterpreted by their clients and colleagues when they initiate a discussion on sexuality,8,9 and only few professionals in Hordern and Street's9 study acknowledged how their private views on sexuality and intimacy might impact on their professional behaviour. Healthcare professionals adopting a patient-centred communication style based on respect and trust were the exception to the rule when it came to discussing patient sexuality and intimacy, perhaps because health professionals rarely perceived patients to be sexual beings.9 Hordern and Street9,10 also found that healthcare professionals make many unchecked assumptions about patient intimacy and sexual needs based on patient's age, diagnosis, disease status, culture and partnership status which resulted in the topic rarely being raised in the clinical setting. Cort et al.28 state that one of the barriers for healthcare professionals to address sexuality are fears about invading on patients' privacy and fears of being too intrusive or causing offence. Professionals may not want to ‘rub sexual issues in their patients' face’, especially not in the case of single people.8 In addition, organisational structures and the existing culture in cancer and palliative care can make it difficult for professionals to discuss sexuality and to show their vulnerable side.8-10

The perspective of patients and partners

Focusing on the patients' and partners' perspective, Redelman17 (based on Hordern and Currow,31 Lemieux et al.32 and Terry et al.33) concludes that research overwhelmingly shows that patients value sexuality and want opportunities to discuss it. The outcomes of the recent study by Flynn et al.19 quantify this conclusion by finding that 78% of their sample of cancer patients (n=819) find it important that healthcare professionals discuss how cancer and cancer treatment affects their sex lives.

Most patients in Hordern and Street's11 study want negotiated, patient-centred communication when it comes to issues of intimacy and sexuality, tailored to their individual needs. Most patients do not take the initiative to ask healthcare providers about sexual problems, although the ones with more serious sexual dysfunctions are more likely to overcome their hesitation.19

Mismatched expectations and unmet needs

In view of the above it is not surprising that Hordern and Street8 found that “there were mismatched expectations between patients and health professionals and unmet patient needs in communication about sexuality and intimacy” (p. 224). A specific factor related to healthcare professionals' reluctance to address sexuality is that to date, little attention in the literature has focused on patients' and partners' preferences regarding health professional communication style about sexuality and intimacy.

To the knowledge of Flynn et al.,19 their USA-based study (based on focus group and survey data) and Hordern and Street's Australian study8 (based on semi-structured interviews) are the only studies that explored patient experiences with communication about sexuality during and after treatment including both sexes across a variety of cancer types. None of these studies included partners of cancer patients. Therefore, the aim of the current European-based study12 (conducted in the Netherlands) was to explore in depth (using open interviews) how a variety of cancer patients and their partners experience the way in which healthcare professionals address sexuality and intimacy. This was complemented with the aim to gain insight into healthcare professionals' perceptions of their role regarding sexuality for cancer patients and their partners. The final aim of the Dutch study was to develop a practical model to tailor professional care to the needs of patients and partners regarding sexual and intimate issues.

Method

The Dutch study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The principles of informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity were adhered to. The study complies with current laws in the Netherlands. As participants (who were all living in their own home at the time of the study) were approached outside healthcare institutions with no involvement of healthcare professionals, no formal ethical approval was needed under the Dutch law. However, in view of the sensitive nature of the study and the vulnerability of the patients and partners participating, advice from a Medical Ethical Committee was used to take measures to optimise the study design and procedures.

Using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, data were collected in the Netherlands through interviewing 15 patients with cancer and 13 partners of patients with cancer (with seven patients and partners being interviewed as a couple34) and 20 healthcare professionals working in cancer and palliative care. Demographic details of the sample are presented in Table 1–2. Patients and partners were mainly recruited from local cancer support centres and cancer rehabilitation support groups and some (having heard about the study and offering to participate) came forward through other networks. In the patient and partner samples maximum variation was strived for regarding age, gender, time elapsed since diagnosis, type and stage of cancer, and type of treatment. Professionals were recruited from the professional network of the researcher (HdV). In the professional sample maximum variation was strived for regarding age, gender, background by discipline, work setting, and years of working experience in cancer and/or palliative care.

Table 1. Demographic and illness-related characteristics of the patients and partners.

| Patients & partners | Patients | Partners |

| Female | 13 | 5 |

| Male | 2 | 8 |

| Age range | 32–71 | 28–72 |

| Time since diagnosis | 2 months – 20 years | n/a |

| Cancer types: breast / cervical / lung / stomach / ovary / mucosa / bowel cancer, Hodgkin's and non Hodgkin's disease | ||

| Treatments: surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, radiation | ||

Table 2. Overview of characteristics of professionals.

| Professionals | Nurses | Doctors | Psychosocial workers |

| Female | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Male | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Age range | 34–59 | 36–65 | 42–50 |

| Years of experience | 3–39 | 7–33 | 1,5–16 |

| Work settings: low care hospice, high care hospice, community, hospital, nursing home, revalidation clinic, GP | |||

All interviews were recorded and transcribed word for word. Data management and initial thematic analysis was supported by the use of ATLAS.ti.35 Analysis was based on the principle of the hermeneutic circle36,37 and was enhanced by peer debriefing. Practical outcomes and recommendations of the study were validated by expert consultation and were presented at multiple (inter)national conferences and workshops, offering the opportunity to discuss the outcomes of the study with healthcare professionals and further refine them.

Results

Patients' and partners' experiences and preferences

Take the initiative to address the ‘real life’ impact

Patients and partners would like health professionals to take the initiative to ‘translate’ information given before treatment about possible side effects into the meaning these side effects might have in real life. Heidi explained what the ‘list of possible side effects of chemotherapy’ turned out to mean for her partner and how this impacted on their sexuality.

Heidi (Par5): I was surprised at the damage to his hands and his feet, and that his nose, ears, anus and penis were affected as well, and because his fingers hurt, he can only touch me with his hands stretched, which is really different sexually. His stomach hurts, so for a year now I couldn't even lay on top of him. I think that at the moment we couldn't even have sex because his penis is covered in blisters. Imagine him having an erection, he'd be in agony, so you wouldn't try and arouse him.

To avoid unnecessary complications, patients and partners stress the importance of being informed pro-actively about the impact of treatment and about possible remedies. When Mia and Ryan were experiencing sexual problems due to vaginal dryness they discussed this with Mia's doctor.

Mia (C2pat): “Well” she [the doctor] said, “we've got Replens” [a lubricant]. But that wasn't really the solution, because the skin in my vagina was already ruined, and it caused irritation so it did more harm than good. Perhaps I should have started using it earlier and then the skin might not have torn.

Participants in this study suggested that healthcare professionals should be the ones to offer the possibility to discuss sexuality and intimacy.

Emma (C3pat): Well at least they should say “do you feel the need to talk about this or do you think you can manage” ... Then they leave it up to the people concerned, but at least they would have mentioned it and reached out.

Person-to-person approach

For patients and partners a prerequisite for discussing intimate issues is a person-to-person approach.

Anna (Pat2): It has to be someone who can actually handle it as a person and who acknowledges me as a person in a normal conversation. When it's done merely professionally you think “there's something wrong with me”.

This prerequisite of a person-to-person approach was not always met.

Edith (C7pat): she [the oncologist] treated us so coldly, she didn't smile at us when we came in and most of the time all we saw was the left side of her face as she was looking at her screen while talking to us. She did not acknowledge that it must be pretty tough to be diagnosed with breast cancer for the second time in one year. She asked why I did not have chemo after my first surgery, as if she was blaming me for it, when all I did was do what my doctor said. That really scared me. We were also afraid that my cancer might be hereditary and we asked about possible consequences for my daughter, but she ignored that.

Professional strategies

Strategies used by professionals to address sexuality do not always work out well for the patient.

Judith (Patl): It was never discussed with me, but I did get some leaflets. They were pushed into my hands, and the gynaecologist said “so much will change in your body and I am giving you these leaflets so you can prepare yourself”, and that was all.

If the prerequisite of a person-based approach is not met, clients will not respond to professional strategies to discuss intimate issues.

Heidi (Par5): All we got every now and then was a letter from the oncology nurse with a list of subjects you could discuss if you wanted to, amongst which was sexuality. But with these people I didn't feel any urge at all to share private matters, because I need a sense of trust with people before I feel able to share such things.

Medicalised solutions for intimate problems

Despite the fact that clients did not always experience their contact with healthcare professionals as being very personal, they sometimes found the courage to ask about a sexual problem.

Emma (C3pat): Before even daring to ask whether you can have sex again you are so worked up and when I finally asked she said “yes, with condoms” and that was all. Nothing else, like “are you worried about that, well you might try this or that”; it was just a three-word technical answer. And that felt a bit crude.

Patients and partners reported that most professionals do not address sexuality and intimacy. Attempts made, often did not match patients' and their partners' preferences, as the following dialogue from a couple interview illustrates.

Walter (C6par): I do remember one question from the gynaecologist: “how's your sex life?” and we answered, “it isn't”.

Joan (C6pat): We didn't really discuss it then.

Walter: No, well, you said something like “it may come back again”. And I remember him saying “we've got medication for that”.

Joan: Then he suggested Prozac for me. And I said “no I don't want that” and then he said, “well perhaps you should consider it”. And that was that.

Without exploring what the experience of this couple was like, or what the nature of their problem seemed to be, this gynaecologist recommended Prozac as a way to solve the problem.

Focus on the whole of the experience

Anna made clear that for her the key thing is to have the opportunity to tell her story to somebody willing to listen, instead of just checking for physical problems.

Anna (Pat2): During treatment the main focus is on symptoms, which in fact is a missed opportunity to ask “and how are things with you?”, and to include the partner: “how are the two of you doing, can you manage?” but we never had these kinds of chats. It was more like lists with questions, where you should just get the opportunity to tell your story.

Patients would also have liked to hear about possibilities instead of just side effects, problems and limitations. They reported lacking the creativity or energy to think of alternatives and would have welcomed suggestions and practical tips from healthcare professionals with experience in guiding and supporting clients in this personal domain.

Emma (C3pat): You can keep focusing on the impossibilities, but I prefer to focus on possibilities. Sometimes you're just not able to think of them yourself.

Age and gender of the professional: does it matter?

Most patients and partners reported that the gender and age of the healthcare professional discussing sexuality and intimacy with them would be irrelevant, although for a few participants these aspects did affect their expectations regarding the professionals' capabilities and willingness to discuss sexuality and intimacy. However, initial expectations based on age and gender of the professional quickly disappeared, as long as patients and partners sensed a genuine interest in them as a person.

Edith and Mike explained:

Mike (C7par): Doesn't matter if it's a man or a woman; it's the type of person that counts.

Edith (C7pat): A younger person would have been fine as long as he or she would have given me the same feeling I experienced from the person I actually met. It could have been an older person as long as I got the feeling that it's me that mattered.

Professionals' perspectives

Avoiding intimate issues

Some professionals reported trying to avoid issues relating to sexuality:

GP (Profl): When patients brought up a sexual issue it was briefly discussed, but not as in depth as it should have been. Next time I just waited to see whether or not the subject was raised again, and I would be really glad if it wasn't. You can encourage people more or less to go in certain directions, and I tried to avoid that area.

Professionals not addressing sexuality and intimacy have described barriers that stop them from providing clients with the opportunity to explore intimate issues, e.g. their own upbringing and socialisation processes or negative sexual experiences. Not all professionals feel they are capable of or have affinity with making authentic, person- to-person contact within their professional role in order to discuss intimacy and sexuality. Some professional participants in the Dutch study made it clear themselves that they did not feel qualified in doing so.

Oncologist (Prof18): Why should a medical oncologist have to deal with that... my job is to treat the cancer of the patient. And the patient may have other problems as well, but the specialist treating the cancer will not deal with a patients' sexuality... And if the patient asks: “Whose job is it then?” he would say “I don't know, but not mine”.

Other professionals pointed out that some of their colleagues did not have what it takes to discuss private issues, no matter how much education and training would be given.

Breast care nurse (Prof13): Doctors still don't pay attention to sexual aspects. Not necessarily because they don't want to but because they don't have the time and because they are not trained to do it. We have one surgeon here that I would not like to even try. Every professional has his area of expertise, and they should stick to that.

Take the initiative to discuss intimate issues

Professionals who did address sexuality and intimacy reported that patients and partners were not offended by a sensitive initiative to discuss sexuality, although some patients made it clear that for them that this is a no-go area.

Specialist oncology nurse (Prof12): Some people say it no longer applies to them and some explain why there is no need to discuss it. But people actually refusing to talk about it, that happened to me only twice.

This specialist nurse and other professionals also warned not to make assumptions (e.g. based on clients' age, religion, relationship status or culture) whether or not it would be relevant to discuss sexual issues. Many professionals reported responses from patients that surprised them, because they contradicted their own expectations.

Breast care nurse (Prof13): I spoke with an elderly couple; she was a widow and he was a widower. All the time he held her hand. And he asked “Is it still okay for me to touch her breast? Not that we still have sex, but we found our own way to be intimate”.

Key theme: worlds apart

The experiences and perceptions of discussing sexuality after cancer of patients, partners and health professionals reflected that they were coming from worlds apart.

The world of health professionals working in cancer and palliative care is primarily based on rationality, evidence, facts, and logic. Professionals are trained to think in terms of linear cancer trajectories based on the functional status of patients and providing cancer and palliative care attuned to this functional status.

In stark contrast, patients and their partners experience a cancer diagnosis as a potentially life threatening event invading all aspects of life. Everything that has meaning for them as a person has the potential of being affected by the cancer diagnosis. Their state of mind is often determined by emotions that are not linear or rational but associative, wavy and circular in nature.

The disparity in communication expectations becomes evident when the ‘lived experience’ from the patient and the partner interfaced with the ‘scientific attitude’ of the professional, with the professional reclassifying the lived experience in ‘objective’ terms of natural science, losing the subjective meaning the experience has for the patient. The gap between these worlds is captured in the key theme ‘worlds apart’. This key theme pervades all communication of healthcare professionals with patients and partners as was illuminated in the quotes from the interviews.

Discussion

A hermeneutic phenomenological approach was utilised in the Dutch study to gain a deep understanding of what and how patients and their partners wished health professionals to communicate about the impact of cancer on intimate and sexual aspects of their lives. The key theme emerging was ‘worlds apart’, supported by Toombs' seminal work,38 illuminating that professionals, especially doctors, are trained to see the body of the patient as a scientific object. For them, the patient's body is an exemplar of ‘the’ human body, and can be studied independently from the patient who is presenting ‘the body’. Taken to its extreme, this means that “the anatomical body represents not the lived body (one's intentional being and mode of access to the world) but rather the cadaver which may be dissected at autopsy”38 (p. 79). Reclassifying the lived experience of patients in terms of natural science tells the doctor ‘what really is the case’, as science is understood as ‘revealing the real truth’.

Sometimes healthcare professionals are able to bridge the gap by engaging in discussions about the ‘lived experience’ of their patients, as for example prof12 and 13 demonstrated, but sometimes, as this study reveals, the gap remains immense. Examples of the different worlds patients live in and professionals work in are not unusual and are reflected in accounts of health professionals who themselves become patients.39-41

For patients and partners, a person-oriented approach is key from the very first time they meet their healthcare professionals. If they do not sense that the professional ‘sees’ the person they are, including their emotional layer and a real life in the world ‘out there’ with everything that comes with it, they will be very hesitant to disclose personal issues. A person-oriented approach is related to the basic attitude of the professionals and the quality of the interaction with patients within the time available. A medicalised, questionnaire-based approach is not conducive for discussing sexuality or intimacy. For the professional it might be a box to tick, for patients and partners it represents the most intimate and emotionally charged information they could think of, and they are not going to reveal private information just like that, not even when they are facing serious problems in the domains of sexuality and intimacy. Therefore professionals are required to be aware of the importance of how questions relating to intimate issues are asked and of how crucial the way they respond to information given is, instead of focusing on the box to tick.

Of course there is a challenge for professionals here, because they do not meet with patients on a personal basis. Patients are not friends they have chosen to meet; they come with the profession. Nevertheless, it is possible to adopt a person-oriented approach within a professional context, as several patients and partners in this study have experienced.

Patient education before treatment

The patients and partners participating in this study made it plain that they would value healthcare professionals taking the initiative to discuss sexuality and intimacy at various stages across the treatment trajectory, e.g. before, during and after treatment.

Patients require pro-active information about the possible side effects treatment could have on their sexuality and intimacy. This is a professionally driven activity, as this is the area of expertise of the professional. Assessing the type of information seeking style the patient has, and adapting the information and support they provide to the individual as a result of that knowledge, can ensure patients are receiving the right information at the right time in the right style to suit their individual needs. At least one professional seeing the patient and partner should ‘translate’ potential medical side effects in a caring way to explain what these might mean in real life, in line with a person-oriented approach. This would also include avoiding heterosexism by not assuming that everybody has one partner of the opposite sex. Many people are single (which does not make them asexual); some people are homosexual or bisexual or have more than one sexual partner. In view of this, as a starting point, it would be better to talk about ‘your partner(s)’ than ‘your wife’ or ‘your husband’.

Patient expertise during/after treatment

As patients may not be fully aware of the enduring impact of treatment on sexuality and the consequences this might have, healthcare professionals have the responsibility to discuss the impact of these side effects. Because there are so many interacting variables impacting on this experience, consequently “there is no uniform, causal model to explain for a certain patient having certain problems regarding sexual functioning”42 (p. 327). Therefore, during and after treatment patients and partners are the experts on what the meaning of this impact is, as this will be different for each patient or partner involved. This should be reflected in a person-oriented communication style when addressing these topics. Patients and partners need to be given the opportunity to consider intimate and sexual concerns arising from their cancer experience. These issues need to be acknowledged by health professionals, validated and further explored or referred on to someone with more expertise. This is crucial as patients who have not had the opportunity to discuss sexual issues with a healthcare professional are significantly more prone to complex sexual dysfunction.18

Ideal world and everyday reality

In an ideal world, every healthcare professional would be capable of adopting a person-oriented communication style regarding sexuality and intimacy, to meet patients' and partners' preferences. However, with competing priorities, time constraints, and lack of experience, peer support and education, it is not realistic to expect the world to be ideal. Informing healthcare professionals that they should communicate with clients about intimacy and sexuality does not mean that these professionals are able and willing to do so,10,16 as this would mean that health professionals have to go “beyond the safety of ‘medicalised’ concepts, which could be communicated in a traditional expert manner”10 (p. 57). For many health professionals this is not an easy step. Professionals who participated in this study as well as the literature8,28 describe barriers that might stop professionals from providing patients and partners with the opportunity to explore sexuality and intimacy issues, e.g. their own upbringing and socialisation processes16 or having negative sexual experiences themselves. Many of these barriers are not likely to be removed easily, as they are deeply rooted in the persons involved.

Team approach: Stepped Skills model

A more realistic and practical way forward might be to think in terms of a complementing team approach. This would involve that, as a starting point, teams discuss what their policy regarding assessing and managing patient sexual and intimate issues is or should be. In order to take these issues seriously, as a team, a ‘sexuality and intimacy including attitude’ needs to be developed. The team (supported by management) needs to acknowledge that sexuality and intimacy are basic and enduring aspects of life, which can contribute to quality of life and are relevant to discuss in the context of cancer and palliative care. This does not mean that every member of the team has to discuss these private topics profoundly with patients and partners. Every team member has stronger and weaker points, and may have different time schemes to adhere to. The art is to think in terms of complementing competencies in order to provide optimal care. A team approach (‘Stepped Skills’) has been developed12 in which different roles regarding addressing sexuality for different team members are described. In ‘Stepped Skills’ there are team members who will be ‘spotting’ (potential) issues relating to sexuality and intimacy and there are team members who will be ‘skilled companions’43 for patients and partners on the road to getting to grips with changing sexuality and intimacy. As a result, team members have clear and complementing roles in order to properly address sexuality and intimacy issues with a clear referral pathway from ‘spotters’ to ‘skilled companions’.

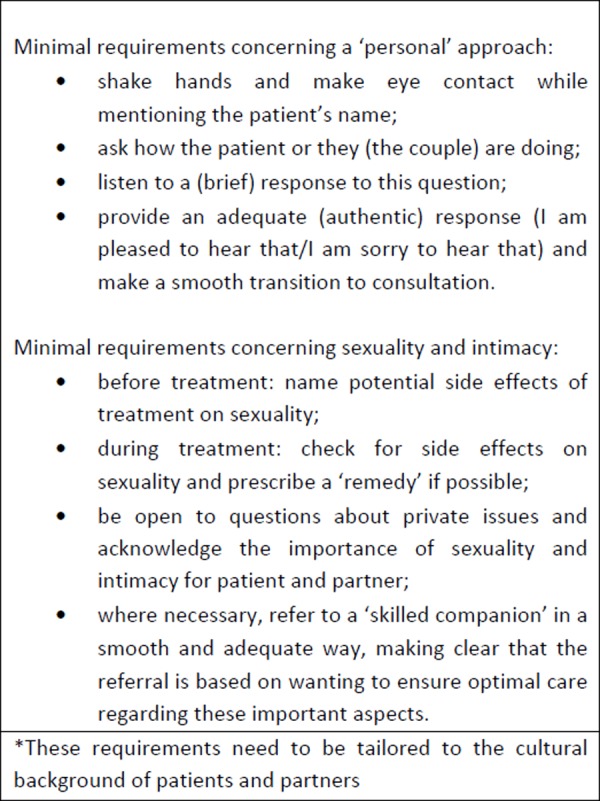

Spotters

Spotters should meet the minimum requirements (Figure 1): create a conducive communication context; discuss the side effects treatment can have on sexual functioning; include these when checking side effects; acknowledge the importance of sexuality and intimacy for patient and partner; refer, where necessary, in a ‘caring’ way to a ‘skilled companion’. These spotters might be relieved to know that their task is a very important but well-delineated one. This might make them willing or give them the confidence to carry out this task, instead of avoiding sexual issues altogether.

Figure 1. Minimal requirements* for ‘spotters’.

Skilled companions

‘Skilled companions’ support patients and partners in all sexual domains related to the effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment: sexual self concept, sexual functioning and sexual relationships. In view of their role description (specialist) nurses would be the most likely candidates to opt for such a role. For patients and partners, the deciding factor is the professional's ability to connect with them on a personal level within a professional role and to feel confident and comfortable discussing sexual issues. Therefore, only those nurses who view patients as sexual beings and have (or would like to adopt) a person-oriented as opposed to a medicalised style of communication, with a drive and desire to be a skilled companion regarding intimate issues, should aspire to this role. Their strength should be their personal quality of relating to other people in a way that will establish sufficient trust to discuss private issues.

Team members require training to develop competencies to match their role. For ‘skilled companions’ this would include knowledge coming from studies exploring and interpreting the lived experiences of cancer patients and their partners regarding the impact of cancer on sexuality and intimacy, education to update their knowledge on sexuality and cancer and some training to optimise their communication competencies. In a future publication a patient and partner-oriented communication model (the ‘BLISSS model’) for discussing sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care, that was developed based on the outcomes of the Dutch study,12 will be described.

Conclusion

All types of cancer and cancer treatment can have an adverse and enduring impact on the experience of sexuality and intimacy. Sexuality and intimacy are important components of quality of life until death. Therefore, sexuality and intimacy should be on the agenda of every cancer and palliative care team.

Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in helping people affected by cancer to understand and to adjust to the sexual and intimate changes that have occurred as a result of their cancer, yet they also need the knowledge, communication skills and confidence to address such sensitive issues with patients in their care. In an ideal world, every healthcare professional would possess all these qualities. However, in view of the personal and practical hindrances some healthcare professionals have regarding addressing intimate issues this does not seem a realistic goal, as both the Australian and the Dutch study demonstrated. Therefore, the Stepped Skills model was developed to provide a realistic and feasible way of addressing sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care teams. Using the model of Stepped Skills, team members can develop clear and complementing roles in order to properly address sexuality and intimacy issues. ‘Spotters’ would have to meet the minimal requirements regarding addressing sexuality and intimacy. Clear referral pathways could navigate patients to designated team members (‘skilled companions’) who are capable of supporting patients and partners in all sexual domains: sexual self concept, sexual functioning and sexual relationships. This would improve cancer care by acknowledging patients with cancer and their partners as sexual beings in need of intimacy by offering them support in dealing with a crucial aspect of quality of life.

The mutual validation of the Australian and European research findings and the approving feedback to international presentations of the Stepped Skills model showed the universality of the problems addressed and the solution offered. Although in the solution different nuances may need to be taken on board to do justice to cultural variation, this article aims to encourage healthcare professionals around the globe to find ways to acknowledge each patient and their partner as a sexual being.

Footnotes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants who gave their time and shared their experiences in the interviews.

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: support was received from Saxion University (De Vocht).

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

The authors confirm that this work was conducted with adequate safeguards and the appropriate approvals.

Please cite this paper as: De Vocht H, Hordern A, Notter J, Van de Wiel H. Stepped Skills: A team approach towards communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care. study. AMJ 2011, 4, 11, 610–619 http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2011.1047

References

- 1.Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J.. Sexuality after gynaecological cancer: A review of the material, intrapsychic, and discursive aspects of treatment on women's sexual-wellbeing. Maturitas. 2011;70:42–57. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleary V, Hegarty J.. Understanding sexuality in women with gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2011. 15(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert E, Ussher J, Perz J.. Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas. 2010;66(4):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins Y, Ussher J, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K.. Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer – The experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2009;32(4):271–80. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5a93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercadante S, Vitrano V, Catania V.. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(6):659–65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Shelby RA, Fawzy MR. et al. Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. PSYCHO ONCOL. 2011;20(4):378–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NCI. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2004. Sexuality and reproductive issues ( physician data query): Health professional version. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Constructions of sexuality and intimacy after cancer: patient and health professional perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(8):1704–18. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hordern A, Street A.. Let's talk about sex: risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemp Nurse. 2007/12;27(1):49–60. doi: 10.5555/conu.2007.27.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hordern A, Street A.. Issues of intimacy and sexuality in the face of cancer: the patient perspective. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(6):E11–E8. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000300162.13639.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vocht HM.. Sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care in The Netherlands: A hermeneutic study. Unpublished thesis submitted for PhD examination 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. WHO working definition of sexuality. [Internet]. 2002. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/sexual_health/en/: Accessed April 27 2011.. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods NF.. Towards a holistic perspective of human sexuality: Alterations in sexual health and nursing diagnosis. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1987;1(4):1–11. doi: 10.1097/00004650-198708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howlett C, Swain M, Fitzmaurice N, Mountford K, Love P.. Education. Sexuality: the neglected component in palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 1997 Jul-Aug;3(4):218–21. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.1997.3.4.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamlin R. In: Palliative care: the nursing role. Lugton J, McIntyre R, editors. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2005. Sexuality and palliative care; pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redelman MJ.. Is there a place for sexuality in the holistic care of patients in the palliative care phase of life? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2008;25(5):366–71. doi: 10.1177/1049909108318569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D.. Sexual morbidity in very long survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106(2):413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn KE, Barsky Reese J, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AA, Lin L, Shelby RA. et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho Oncol. 2011;10(1002/pon.947) doi: 10.1002/pon.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnan MA, Reynolds KE, Galvin EA.. Barriers to addressing patient sexuality in nursing practice. Medsurg Nursing. 2005;14(5):282–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunamaki N, Andersson M, Engstrom M.. Discussing sexuality with patients: nurses' attitudes and beliefs. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1308–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich ER. et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivor's sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.25832. doi 10.1002/cncr.25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peate I.. Clinical. Taking a sexual health history: the role of the practice nurse. Br J Nurs. 1997. 8 Oct 25;6(17):978–83. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1997.6.17.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stead M, Fallowfield L, Brown J, Selby P.. Communication about sexual problems and sexual concerns in ovarian cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2001 Oct 13;323(7317):836–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7317.836. 2001/10/13/2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P.. Communication about sexual problems and sexual concerns in ovarian cancer: A qualitative study. West J Med. 2002;176(1):18–9. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.176.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P.. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:666–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gott M, Galena E, Hinchliff S, Elford H.. “Opening a can of worms”: GP and practice nurse barriers to talking about sexual health in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):528–36. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cort E, Monroe B, Oliviere D.. Couples in palliative care. Sex Relationship Ther. 2004;19(3):337–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes MK.. Sexuality and cancer: The final frontier for nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(5):E241–E6. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E241-E246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fobair P,, Spiegel D.. Concerns about sexuality after breast cancer. Cancer Journal. 2009;15:19–26. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hordern AJ, Currow DC.. A patient-centred approach to sexuality in the face of life-limiting illness. Med J Aust. 2003;179:S8–S11. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemieux L, Kaiser S, Pereira J, Meadows LM.. Sexuality in palliative care: patientperspectives. Palliat Med. 2004;18:630–7. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm941oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terry W, Olson LG, Ravenscroft P, Wilss L, Boulton-Lewis G.. Hospice patient's views on research in palliative care. Intern Med. 2006;36(7):406–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor B, De Vocht HM.. Interviewing separately or as couples? Considerations of authenticity of method. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:1576–87. doi: 10.1177/1049732311415288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewins A, Silver C. London: Sage; 2007. Using software in qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gadamer H-G. In: Conolly JM, Keutner T, editors. University of Notre Dame Press; 1988. On the circle of understanding; pp. 68–78. Hermeneutics versus science? Three German views. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gadamer H-G. New York: Crossroad: 1960/1982. Truth and method. (Original work published 1960) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toombs SK. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. The meaning of illness. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks O. Clearwater: Touchstone Books; 1984. A leg to stand on. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenbaum EE. New York: Random House; 1988. A taste of my own medicine: when the doctor is the patient. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ten Haaft G.. Dokter is ziek [The doctor is ill] 2010 Amsterdam: Contact. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pool G, Wiel HBMvd, Jaspers JPC, Weijmar Schultz WCM, Driel MFv. Kanker.. Gianotten WL, Meihuizen-de Regt MJ, Son-Schoones MJv, editors. Seksualiteit bij lichamelijke ziekte en beperking. Assen: Van Gorcum. 2008:325–39. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Titchen A. Oxford: Ashdale Press; 2000. Professional craft knowledge in patient centred nursing and the facilitation of its development. [Google Scholar]