Abstract

Objective

Report maternal perceptions of antenatal care provision and identify deficiencies in the current model of care provision.

Methods

A survey was conducted to record maternal views about quality of antenatal consultations provided at a tertiary level hospital. Trained nurses and female health workers interviewed the patients attending antenatal visits during the month of July 2009. A standard questionnaire was use to enter the responses. Data were entered into the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for appropriate statistical analysis of the results. Data analysis generated two groups. One group had up to 4 antenatal visits and the other group had more than 4 visits.

Results

Responses were obtained for 244 patients. Chi-square test was applied for the comparison of variables between the two groups. Significantly higher number of women preferred to follow the 4 visit care plan (n=118/244 vs. n=103/244, respectively; p=0.004). Patient satisfaction was also significantly higher among women in the 4 visit group (n=112/244 vs. n=90/244; p=0.04). More than 50% of patients said that they did not receive any information about the process of labor, breast-feeding or contraception.

Conclusion

Women included in the study did not want frequent visits to antenatal clinic. Efforts should be made to provide information about labor, breast-feeding and contraception.

Keywords: Antenatal, Care provision, Maternal, Views

Introduction

Motherhood is an important aspect of a woman’s life. Antenatal visits at healthcare facility are meant to ensure safe outcomes for mothers and babies alike. Good patient doctor relationship and the overall facilitation by staff can promote patient satisfaction and trust. It is the prime duty of a healthcare providers to be aware of the patients' needs. Moreover, modern concept of changing childbirth stresses on the involvement of patient choices at all times during care provision. In a review article by Baldo M.H., a debate about optimum antenatal care has focused on reducing the number of antenatal visits to an effective and efficient minimum; ensuring satisfaction of both the providers and receivers of care.1

Globally, agencies like World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) emphasize to improve maternal health through preventing unplanned and high-risk pregnancies by providing care in pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period to save women’s lives. A randomized controlled trial was conducted by WHO in four countries; Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Cuba and Thailand. The aim was to assess women and provide satisfaction with a new evidence based antenatal care model vs. the traditional care model for low risk women.2

This survey was done at Women specialized hospital (WSH), Riyadh to determine the level of patient comfort and help provide an insight into many administrative issues and policy making, in order to improve satisfaction from the receiver's as well as provider's points of view.

Methods

A survey was conducted to record maternal views about the quality of antenatal consultations provided at WSH during the month of July 2009. Women travelled to the hospital in their private transport from within the city of Riyadh, approximately from within a radius of 100 metres. Trained nurses and female health workers interviewed the patients attending antenatal visits. A standard questionnaire (QCW) devised by WHO for assessment of antenatal care in Saudi Arabia was used to enter the responses.2 The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and all instructions on the questionnaire were strictly followed. Every fifth woman attending the routine antenatal clinic was interviewed, ensuring randomization of the sample. Up to 25-30 women were interviewed daily. The participants gave their consent before recording responses and patient identification was anonymized after initial data collection. High-risk pregnancies were excluded from the survey. Entries were checked periodically and feedback was taken from the nurses as well as the patients. Antenatal care guidelines followed at WSH include the traditional care plan with 12-14 routine visits during the course of a pregnancy. No intervention was made in the routine care plan.

Information was collected about frequency and quality of antenatal visits, acceptance of male physicians as care providers, adequacy of information provided about pregnancy complications, lactation, childbirth, and contraception. Overall satisfaction with the service provided was also assessed.

Data analysis generated two groups based on the frequency of antenatal visits. One group had more than 4 visits while the other group had up to 4 antenatal visits. The patients in the latter group decided to come less frequently to suit their own comfort and by choice missed their scheduled appointments. Patient preference for the frequency of antenatal consultations and satisfaction levels were compared between the two groups. Permission was taken from the Institutional review board (IRB) before starting the survey. Biostatistician support was sought for statistical analysis. Results were calculated and statistical analysis was done using the SPSS package by adopting the Pearson chi-square test with a degree of freedom=2 and p=0.05.

Results

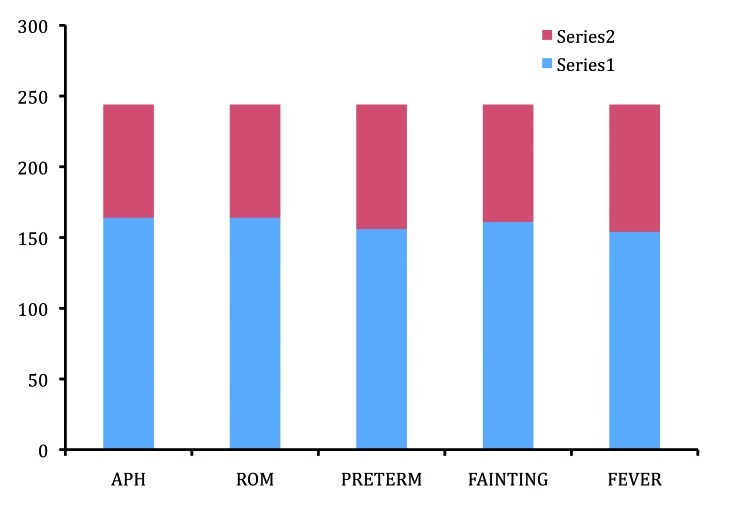

Two hundred and forty-four women were included in the survey. Data analysis showed that 55.3% (135/244) had upto 4 antenatal visits, while 44.7% (109/244) had more than 4 visits. Also, 67.6% (165/244) expressed preference for a female physician, while 27.2% (69/244) had no gender bias and 4.1% (10) wanted to be seen by a male physician. The results also showed that 82.8% (202/244) were worried about fetal malposition and 80% (195/244) had their queries answered. In addition, 85.7% (209/244) wanted to know the estimated fetal weight and 71% (173/244) had to know it. Fig. 1 shows the counts of information provided about possible pregnancy complications. The patient responses to queries related to the dissemination of information about the process of labor, breast feeding and contraception during antenatal consultations are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

A count of maternal perception of information about common antenatal complications (n=244). APH= Antepartum hemorhage, ROM= Rupture of membranes. Series 1= confirmed provision of information Series 2= Denied provision of information

Table 1. Percentage distribution of maternal perception of information about peripartum practices. (n=244).

| Variable | No information n (%) |

Information given n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Labor process | 167 (68.44) | 77 (31.55) |

| Breast feeding | 192 (78.68) | 52 (21.3) |

| Contraception | 212 (86.88) | 32 (13.1) |

A significantly higher number of women preferred to follow the 4 visit care plan (n=118/244 vs. n=103/244, respectively; p=0.004). Patient satisfaction was also significantly higher among women in the 4 visit group (n=112/244 vs. n=90/244; p=0.04).

In addition, 87.7% (214/244) felt unhappy because they had to wait upto one hour before being seen by the physician. All women expressed concerns about their pregnancy. While 84.8% (207/244) of the women were worried about their own health in general and 86.5% (211/244) were concerned if their weight gain is optimal or not. Furthermore, 63.1% (154/244) were satisfied with information about their treatment, while 18.9% (46/244) thought that information was not enough, and 17.25 (42/244) said that they did not receive any information about their treatment. On the other hand, 71% (173/244) of the women said they would like to visit WSH clinic again for their next pregnancies, while 8.2% (20/244) said they would not. Also, 67.2% (164/244) said they would recommend their family and friends to visit the clinic for antenatal care, while 12.7% (31/244) reported against recommending the clinic to their family and friends. It was also noted from the results that 21% (49/244) of the women were not sure whether or not they would like to visit the clinic again, and an equal segment of the women were unsure whether or not they would recommend the clinic to their family and friends.

Discussion

The traditional model of antenatal care included 12-14 visits.2 A debate began in the last two decades about established antenatal care schedules. The debate mainly focuses on comparison between the traditional care plan and the new antenatal care plan with reduced visits. The present study can be considered as a pilot project to record the maternal perceptions about the quality of antenatal care provision at a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh.

WHO used intervention clinics in the first large randomized trial to evaluate the impact of the new schedule of care comprising of 4 visits vs. the traditional 12-14 visits. It was a randomized controlled trial to test the benefits of a new antenatal care program for low risk women. In the intervention clinics, women judged not to be needing further special care at the time of the first visit were assigned the new antenatal care model with fewer appointments (usually four).Women in the intervention clinics were significantly more satisfied with the general information they received.2

The present study did not have an intervention group but the WHO, QCW was used to record patient responses to queries regarding the quality of antenatal care. Patient response analysis showed that women with less frequent antenatal visits exhibited higher levels of satisfaction with service provision and women who had more frequent visits preferred to be seen less frequently. The majority of women disliked to wait for their turn before being seen by the physician. Another similar study conducted by Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia found that women wanted less than ten antenatal visits before delivery.3

Also, two studies were conducted to identify reasons for poor antenatal attendance in the northern region and Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia in 1997 and 2007, respectively. The majority of non-attendees thought that pregnancy is a normal state and does not need additional care.4,5 An article published on the basis of maternal and child health survey, 1991, also mentioned that almost one third of non-attendees of antenatal clinics believed the same.

All Women interviewed at WSH, Riyadh, were concerned about their own health and wanted information about their own weight gain, fetal size and position, as well as details of any treatment given.

Conclusion

Overall, women seen at WSH, Riyadh, were concerned about their pregnancy. They wanted less frequent consultations but expected quality content. It calls for the need of more detailed explanation by the healthcare provider about the progress at each visit. Efforts should be made to shorten the waiting time and provide information about the process of labor, lactation and contraception in the form of printed leaflets or video demonstrations in the clinics to keep the women busy while they wait for their turn.

Acknowledgements

The authors reported no conflict of interest and no funding was received for this work.

References

- 1.Baldo MH. The antenatal care debate. East Mediterr Health J 2001. Nov;7(6):1046-1055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer A, Villar J, Romero M, Nigenda G, Piaggio G, Kuchaisit C, et al. Are women and providers satisfied with antenatal care? Views on a standard and a simplified, evidence-based model of care in four developing countries. BMC Womens Health 2002. Jul;2(1):7 www.biomedcentral.com Accessed 11th Aug 2011. 10.1186/1472-6874-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel H, Yahia A. Failure to register for antenatal care at local primary health care centers. Ann Saudi Med 2000;20:3-4p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdul H, Adel W. Antenatal care in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia: A situation analysis. Middle Eastern journal of family medicine. 2009; 7: 4-12p.

- 5.al-Nasser AN, Bamgboye EA, Abdullah FA. Providing antenatal services in a primary health care system. J Community Health 1994. Apr;19(2):115-123 10.1007/BF02260363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]