Abstract

Previous studies have implicated a role of Gαi proteins as co-regulators of Toll –like receptor (TLR) activation. These studies largely derived from examining the effect of Gαi protein inhibitors or genetic deletion of Gαi proteins. However the effect of increased Gαi protein function or Gαi protein expression on TLR activation has not been investigated. We hypothesized that gain of function or increased expression of Gαi proteins suppresses TLR2 and TLR4 -induced inflammatory cytokines. Novel transgenic mice with genomic “knock-in” of a Regulator of G-protein Signaling (RGS)-insensitive Gnai2 allele (Gαi2 G184S/G184S; GS/GS) were employed. These mice express essentially normal levels of Gαi2 protein, however the Gαi2 is insensitive to its negative regulator RGS thus rendering more sustained Gαi2 protein activation following ligand/receptor binding. In subsequent studies, we generated Raw 264.7 cells that stably overexpress Gαi2 protein (Raw Gαi2). Peritoneal macrophages, splenocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were isolated from WT and GS/GS mice and were stimulated with LPS, Pam3CSK4 or Poly (I:C). We also subjected WT and GS/GS mice to endotoxic shock (LPS 25mg/kg i.p.) and plasma TNFα and IL-6 production were determined. We found that in vitro LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα and IL-6 production are decreased in macrophages from GS/GS mice compared with WT mice (p<0.05). In vitro LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced IL-6 production in splenocytes and in vivo LPS induced IL-6 were suppressed in GS/GS mice. Poly (I:C) induced TNFα and IL-6 in vitro demonstrated no difference between GS/GS mice and WT mice. LPS induced IL-6 production was inhibited in MEFs from GS/GS mice similarly to macrophage and splenocytes. In parallel studies, Raw Gαi2 cells also exhibit decreased TNFα and IL-6 production in response to LPS and Pam3CSK4. These studies support our hypothesis that Gαi2 proteins are novel negative regulators of TLR activation.

Keywords: Gαi protein, TLR signaling, LPS, endotoxemia, inflammatory cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is the clinical manifestation of a systemic maladaptive host response to invasive infection. Sepsis leading to septic shock and multiple organ failure is the leading cause of death in intensive care units and remains a major health problem in the United States and worldwide [1,2]. The interaction of bacterial components such as LPS, peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, and exotoxins with macrophages, monocytes, endothelial cells or other host cells induces the release of inflammatory mediators that play a major role in the pathophysiology of septic shock [3,4].

The Toll-like receptor (TLR) family plays a critical role in mediating the innate and adaptive immune response [5]. The Gram-negative bacteria cell wall component LPS-induced signaling is mediated by TLR4 coupled with CD14 and MD-2 [6]. Lipoprotein from the Gram-positive bacteria -induced signaling pathways is mediated, in part, through TLR2 and other receptors [7]. Pam3CSK4 is a synthetic triacylated lipoprotein signaling through TLR1/2 [8]. TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA along with its synthetic analog, polyinosinedeoxycytidylic acid (Poly I:C) [5]. Stimulation of TLR2, TLR3 or TLR4 signaling pathways results in activation of a series of signaling proteins leading to expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine genes [9]. These cytokines and chemokines contribute to the complex inflammatory milieu of sepsis.

Heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide binding regulatory (G) proteins of the G inhibitory class (Gi) are involved in signaling to microbial stimuli. Our recent studies demonstrated that Gαi proteins were directly activated by LPS [10]. Inhibition of Gαi protein with pertussis toxin (PTx) augment LPS induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo [11–14]. In addition to pharmacologic inhibition of Gαi protein, mice with genetic deletion of Gαi2 protein exhibit an enhanced inflammatory response and reduced survival in response to cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis [10]. Collectively, these findings suggest an anti-inflammatory role of Gαi proteins in inflammatory response.

Since inhibition of Gαi protein augments the inflammatory response, we hypothesized that increased Gαi protein function or overexpression of Gαi protein will suppress TLR induced inflammation. WT and novel transgenic mice with genomic knock-in of a RGS-insensitive Gαi2 (GS/GS) were employed [15]. The TLR4 ligand LPS, TLR2 ligand Pam3CSK4 and TLR3 ligand Poly (I:C) induced TNFα and IL-6 production in splenocytes, macrophage and MEFs were determined. LPS shock induced plasma TNFα and IL-6 production were assessed in GS/GS vs WT mice. In subsequent studies, Raw 264.7 cells stably expressing control vector and Gαi2 proteins were generated. LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα and IL-6 production were determined. Collectively these demonstrate an anti-inflammatory function of Gαi2 proteins in regulating TLR induced inflammatory response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Gαi2 G184S/G184S (GS/GS) mice and littermate WT mice with C57BL/6 background were generated by breeding heterozygous mice as described previously [15]. Studies employed 7 to 9 week old GS/GS and age matched WT mice. The gain of function Gαi2 G184S/G184S mice were obtained from Dr. Richard R. Neubig. (University of Michigan) The investigations conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health and operated under the approval of the institutional animal care and use committee.

Raw Gαi2 cell line

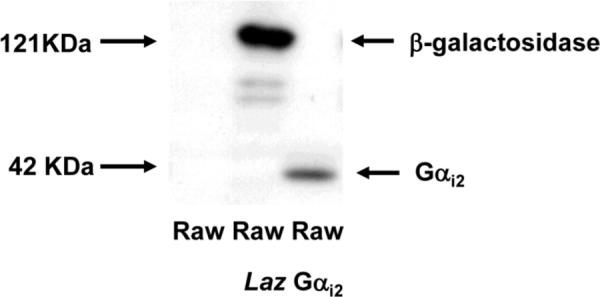

WT human Gαi2 gene was cloned into a ViraPower Lentiviral Expression System using pLenti6/V5 directional TOPO cloning kit. A pLenti6/V5-GW/lacZ plasmid was used as a control plasmid. Lentivirus containing Gαi2 and control vector were generated following manufacture's instructions (Invitrogen). Raw 264.7 cells were transduced with lentivirus and selected by Blasticidin to generate the Raw cells lines stably expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase. Since the pLenti6/V5 vector contains a V5 tag sequence, a V5 antibody was used to detect the overexpression of target protein. A representative Western blot shows the overexpression of Gαi2 and β-galactosidase in Raw cell lines (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Raw 264.7 cell lines expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase.

Raw 264.7 cell line and Raw cells lines stably expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase were subjected to Western blot analysis. An anti-V5 antibody was used to detect the overexpression of target protein. The band at 121 KDa is vector control (Raw Laz) corresponds to β-galactosidase. The 42 band corresponds to overexpressed Gαi2 in Raw Gαi2 cells

Cell culture and stimulation

RAW 264.7 cells stably expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with heat inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (Cellgro Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA), 2% Penicillin/streptomycin (BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, MD) and 2ug/ml Blasticidin (Invitrogen) in 150 cm2 tissue culture flasks and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2, 95% air. The confluent cells were detached using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and passaged every 2–3 days. RAW 264.7 cells within 20 passages were used for experiments.

RAW 264.7 cells expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase were stimulated with LPS (10ng/ml, ultra-pure LPS from Escherichia coli O111:B4, List Laboratories, Campbell, CA), Pam3CSK4 (1μg/ml, Invivogen) or Poly (I:C) (10μg/ml Invivogen) for 24 hours. LPS-induced TNFα and IL-6 production were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA).

Peritoneal macrophages, splenocytes and MEFs were isolated from GS/GS mice and littermate WT mice as previously described [10,16,17] and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro Mediatech Inc., Herndon, VA), supplemented with heat inactivated 1% fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 50U/ml penicillin, 50μg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro Mediatech Inc., VA). The macrophage (1×106 cells/well) were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Non-adherent cells were washed off. Typically, more than 95% of macrophages were obtained as examined by stain with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (Caltag) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Macrophages were stimulated with 10ng/ml of LPS, 1μg/ml of Pam3CSK4 and 10μg/ml Poly (I:C) for 24 hours. Splenocytes (5×106 cells/well) in 24-well plates were stimulated with 10ng/ml of LPS, 1μ/ml of Pam3CSK4 and 10μg/ml Poly (I:C) for 24 hours. MEFs were stimulated with LPS (10ng/ml) for 24 hours. The supernatants were collected for assay of mediator production.

Endotoxemia

Endotoxemia was induced by intraperitoneal injection of LPS (25mg/kg). Six hours later plasma was taken for TNFα and IL-6 measurements.

Western blot

The Raw cells expressing Gαi2 and β-galactosidase were washed and lysed with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin A). The supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until Western blot analysis.

For Western blotting, lysates were added to Laemmli sample buffer and boiled for 4 min. Subsequently, protein from each sample was subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST; 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.15% Tween 20) and blocked with 5% milk in TBST (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. After being washed twice with TBST (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20), membranes were incubated with polyclonal anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed twice with TBST (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with HRP conjugated secondary antibody in blocking buffer for 1 h. After being washed three times with TBST (TBST; 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.15% Tween 20), immunereactive bands were visualized by incubation with ECL plus detection reagents (GE Healthcare) for 5 min and exposure to ECL Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare). The densitometry of bands was quantified with NIH image software.

Assay for TNFα and IL-6 production

TNFα and IL-6 production were measured using an ELISA with mouse TNFα or IL-6 ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's probable least-squares difference test or students' t Test using GraphPad Prism software. A p<0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

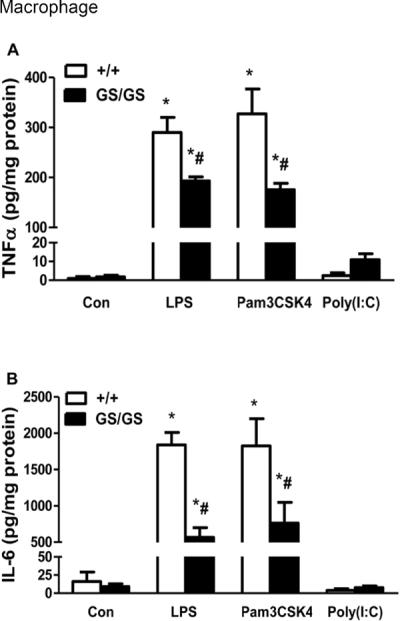

Gain of function of Gαi2 suppresses LPS and Pam3CSK4-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in macrophage

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from WT and GS/GS mice and stimulated with the TLR4 ligand LPS, TLR2 ligand Pam3CSK4 and TLR3 ligand Poly (I:C) for 24 hours. LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα (Fig. 2A) and IL-6 (Fig. 2B) production were decreased (33±3% and 46±4%; 69±7% and 58±16% respectively, p<0.05) in GS/GS mice compared with WT mice. Poly (I:C) induced TNFα and IL-6 production was not different between GS/GS mice with WT mice (Fig. 2A, 2B).

Figure 2. Effect of gain of function of Gαi2 protein on LPS and Pam3CSK4-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in peritoneal macrophage and splenocytes.

Peritoneal macrophage and splenocytes were isolated from WT and GS/GS mice and stimulated with LPS and Pam3CSK4 for 24 hours. LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα (A) and IL-6 (B) production in peritoneal macrophages and TNFα (C) and IL-6 (D) production in splenocytes were determined. *, p<0.05 compared to basal group; #, p<0.05 compared to WT group. N=3.

Gain of function of Gαi2 decreases LPS and Pam3CSK4-induced IL-6 but not TNFα production in splenocytes

Splenocytes were isolated from WT and GS/GS mice and were stimulated with LPS, Pam3CSK4 and TLR3 ligand Poly (I:C) for 24 hours. There was no difference between WT and GS/GS mice in LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα production in splenocytes (Fig. 2C). However, LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced IL-6 production was decreased (64±13% and 70±4% respectively, p<0.05) in GS/GS mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 2D). Poly (I:C) induced TNFα and IL-6 production was not different between GS/GS mice with WT mice (Fig. 2C, 2D).

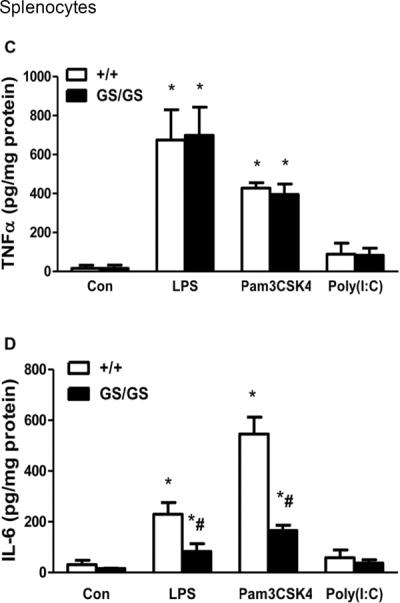

Gain of function of Gαi2 inhibits LPS-induced IL-6 production in MEFs

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were isolated from WT and GS/GS mice and were stimulated with LPS for 24 hours. LPS induced IL-6 production in MEFs was decreased (65±2%, p<0.05) in GS/GS mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effect of gain of function of Gαi2 protein on LPS-induced IL-6 production in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF).

MEFs were isolated and cultured from WT and GS/GS mice and stimulated with LPS and Pam3CSK4 for 24 hours. LPS induced IL-6 production was determined by ELISA. *, p<0.05 compared to basal group; #, p<0.05 compared to WT group. N=6.

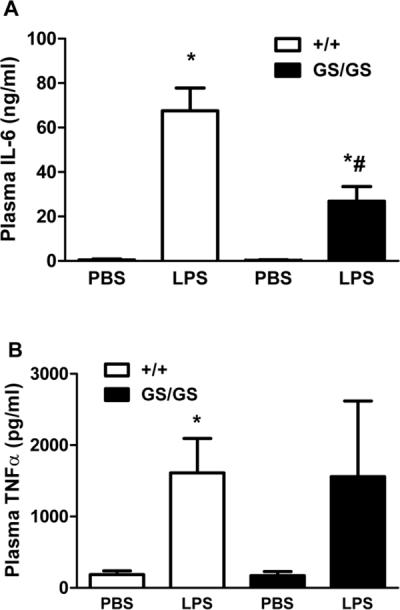

Gain of function Gαi2 mice exhibit decreased plasma IL-6 production compared to wild type mice in response to endotoxemia

WT and GS/GS mice were subjected to endotoxemia. In GS/GS mice, LPS-induced plasma TNFα was not significant different from WT mice (Fig. 4A). However LPS-induced IL-6 production was significantly decreased (60±10%, p<0.05, Fig. 4B) in GS/GS mice compared to WT mice.

Figure 4. Effect of gain of function of Gαi2 protein on LPS -induced plasma TNFα and IL-6 production in mice.

WT and GS/GS mice were subjected to endotoxemia for 6 hours and LPS-induced plasma TNFα (A) and IL-6 (B) production were determined. *, p<0.05 compared to basal group; #, p<0.05 compared to WT group. N=4–6.

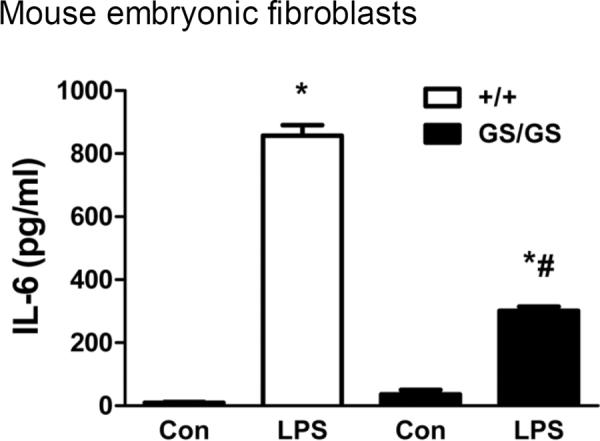

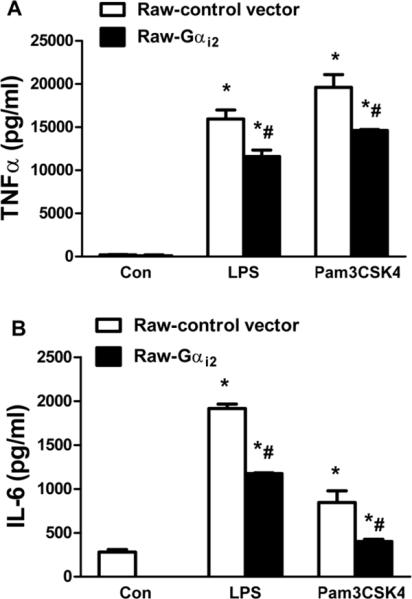

Overexpression of Gαi2 protein decreases LPS and Pam3CSK4-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in Raw cell lines

The lentiviral expression system was used to generate Raw 264.7 cells that stably overexpressed Gαi2 protein (Raw Gαi2) and β-galactosidase (Raw-control vector). LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα and IL-6 production were determined by ELISA. The Raw Gαi2 cells exhibited decreased TNFα (27±5% and 25±1% respectively, p<0.05, Fig 5A) and IL-6 (39±0.4% and 52±3% respectively, p<0.05, Fig 5B) production in response to LPS and Pam3CSK4.

Figure 5. Effect of overexpression of Gαi2 protein on LPS and Pam3CSK4-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in Raw 264.7 cells.

Raw 264.7 cells that stably overexpressing Gαi2 protein (Raw Gαi2) and α-galactosidase (Raw-control vector) were employed. Cells were stimulated with LPS and Pam3CSK4 for 24 hours. LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα (A) and IL-6 (B) production were determined by ELISA. *, p<0.05 compared to basal group; #, p<0.05 compared to WT group. N=3.

DISCUSSION

These studies provide the first evidence that gain of function of Gαi2 protein suppresses LPS and Pam3CSK4 induced inflammatory cytokines. We found that TLR4 ligand LPS and TLR2 ligand Pam3CSK4 induced TNFα and IL-6 production were decreased in peritoneal macrophages and IL-6 in splenocytes from gain of function of Gαi2 mice. Gain of function of Gαi2 protein also inhibited LPS-induced IL-6 production in MEFs. LPS-induced plasma IL-6 production was decreased in gain of function of Gαi2 mice compared to WT mice. The response of Raw 264.7 cell lines overexpressing Gαi2 protein to TLR2 and TLR4 ligands also support the notion that Gαi2 protein suppresses TLR2 and TLR4 ligand induced inflammatory cytokines.

Our previous studies and others' demonstrated that mastoparan (MP)-7, which activates Gαi proteins reduce LPS-induced inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo [10,12,14]. Lentschat et al. demonstrated that MP-7 differentially regulate TLR2 and TLR4 activation [11]. In contrast to MP-7, pretreatment with PTx, which inhibits Gαi proteins significantly augments LPS induced inflammatory cytokines in vivo whereas PTx without LPS also did not induce an inflammatory response [10]. However a limitation of MP-7 or PTx is that it is not Gαi isoform specific and as with any pharmacologic agent may have other effects. Our current studies employing isoform specific targeting suggest that Gαi2 protein regulates both TLR2 and TLR4 signaling. We also employed TLR3 ligand Poly (I:C) in our studies. Interestingly we found that Poly (I:C) induced only modest TNFα and IL-6 production in macrophage and splenocyte from WT mice. Gain of function of Gαi2 proteins exhibited no effect on Poly(I:C) induced TNFα and IL-6 production. Similar results were observed when Gαi2 protein were overexpressed in Raw 264.7 cells and stimulated the cells with TLR ligands. Since both TLR2 and TLR4 activate MyD88 signaling and TLR3 activates Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β (TRIF) signaling [5], these data suggest that Gαi protein may only regulate MyD88 dependent signaling and have no effect on TRIF dependent signaling in macrophage and splenocytes.

The mechanism by which Gαi proteins inhibits TLR-induced inflammation is being intensively investigated. Our previous studies demonstrated that a Gαi2 minigene plasmid or dominant negative Gαi3 blocked TLR4 induced ERK1/2 activation in HEK293 cells [13]. In endothelial cells, PTx suppressed ERK 1/2 and AKT induced by TLR activation independent of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) [14]. Both ERK 1/2 and PI3 kinase induced signaling may have anti-inflammatory effects [18,19].

It has been demonstrated that TLR4 clusters with multiple receptors upon LPS stimulation [20]. For example the G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) CXCR4 which is coupled to Gi protein has been postulated as a co-regulator of TLR4 [20]. Blocking antibodies to CXCR4 increase TLR4 activation whereas a CXCR4 ligand reduces TLR4 activation [21,22]. Also in Raw264.7 cells we have demonstrated that LPS directly activates Gαi protein determined by an increase the active Gαi-GTP complex [10]. Thus TLR receptors may directly activate Gαi proteins perhaps through a consensus motif for binding Gαi in the TLR intracellular domain [14,23]. Alternatively but not exclusively ligand binding to TLRs may indirectly activate Gαi proteins through transactivation of GPCRs or through autocrine pathways eg. CXCR4 ligands [14,22]. Thus activation of Gαi signaling may constitute a novel negative feedback to limit TLR induced inflammation. Our findings that gain of function Gαi2 cells and mice and overexpression of Gαi2 supress TLR2 and TLR4 activation are consistent with such as hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by GM27673 (JAC), GM67202 (BZ), AI079248 (HF) and UL1RR029882 and UL1TR000062 (SCTR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–10. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weycker D, Akhras KS, Edelsberg J, Angus DC, Oster G. Long-term mortality and medical care charges in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2316–23. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000085178.80226.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karima R, Matsumoto S, Higashi H, Matsushima K. The molecular pathogenesis of endotoxic shock and organ failure. Mol Med Today. 1999;5(3):123–32. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone RC. Why sepsis trials fail. JAMA. 1996;276(7):565–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akashi S, Shimazu R, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Takeda K, Kimoto M, Miyake K. Cutting edge: cell surface expression and lipopolysaccharide signaling via the toll-like receptor 4-MD-2 complex on mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164(7):3471–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their signaling mechanism in innate immunity. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59(3):124–30. doi: 10.1080/000163501750266701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel M, Xu D, Kewin P, Choo-Kang B, McSharry C, Thomson NC, Liew FY. TLR2 agonist ameliorates established allergic airway inflammation by promoting Th1 response and not via regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):7558–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(8):675–80. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan H, Li P, Zingarelli B, Borg K, Halushka PV, Birnbaumer L, Cook JA. Heterotrimeric Gα(i) proteins are regulated by lipopolysaccharide and are anti-inflammatory in endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(3):466–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lentschat A, Karahashi H, Michelsen KS, Thomas LS, Zhang W, Vogel SN, Arditi M. Mastoparan, a G protein agonist peptide, differentially modulates TLR4- and TLR2-mediated signaling in human endothelial cells and murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174(7):4252–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon KR, Kurt-Jones EA, Saladino RA, Stack AM, Dunn IF, Ferretti M, Golenbock D, Fleisher GR, Finberg RW. Heterotrimeric G proteins physically associated with the lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14 modulate both in vivo and in vitro responses to lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(11):2019–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan H, Peck OM, Tempel GE, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Toll-like receptor 4 coupled GI protein signaling pathways regulate extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation and AP-1 activation independent of NFkappaB activation. Shock. 2004;22(1):57–62. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000129759.58490.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dauphinee SM, Voelcker V, Tebaykina Z, Wong F, Karsan A. Heterotrimeric Gi/Go proteins modulate endothelial TLR signaling independent of the MyD88-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(6):H2246–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01194.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang X, Fu Y, Charbeneau RA, Saunders TL, Taylor DK, Hankenson KD, Russell MW, D'Alecy LG, Neubig RR. Pleiotropic phenotype of a genomic knock-in of an RGS-insensitive G184S Gnai2 allele. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(18):6870–9. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00314-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan H, Bitto A, Zingarelli B, Luttrell LM, Borg K, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Beta-arrestin 2 negatively regulates sepsis-induced inflammation. Immunology. 2010;130(3):344–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan H, Zingarelli B, Peck OM, Teti G, Tempel GE, Halushka PV, Spicher K, Boulay G, Birnbaumer L, Cook JA. Lipopolysaccharide- and gram-positive bacteria-induced cellular inflammatory responses: role of heterotrimeric Galpha(i) proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289(2):C293–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00394.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao YQ, Freire-de-Lima CG, Janssen WJ, Morimoto K, Lyu D, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Oxidants selectively reverse TGF-beta suppression of proinflammatory mediator production. J Immunol. 2006;176(2):1209–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao YQ, Malcolm K, Worthen GS, Gardai S, Schiemann WP, Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Cross-talk between ERK and p38 MAPK mediates selective suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(17):14884–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triantafilou K, Triantafilou M, Dedrick RL. A CD14-independent LPS receptor cluster. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(4):338–45. doi: 10.1038/86342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan H, Wong D, Ashton SH, Borg KT, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Beneficial effect of a CXCR4 agonist in murine models of systemic inflammation. Inflammation. 2012;35(1):130–7. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9297-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishore SP, Bungum MK, Platt JL, Brunn GJ. Selective suppression of Toll-like receptor 4 activation by chemokine receptor 4. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(3):699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto T, Nishimoto I, Murayama Y, Ohkuni Y, Ogata E. Insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor is incapable of activating GTP-binding proteins in response to mannose 6-phosphate, but capable in response to insulin-like growth factor-II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168(3):1201–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91156-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]