Abstract

Introduction

Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors have less upper gastrointestinal toxicity than traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, both COX-2 inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs may be associated with adverse cardiovascular side effects. Data from randomised and observational studies suggest that celecoxib has similar cardiovascular toxicity to traditional NSAIDs. The overall safety balance of a strategy of celecoxib therapy versus traditional NSAID therapy is unknown. The European Medicines Agency requested studies of the cardiovascular safety of celecoxib within Europe. The Standard care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT) compares the cardiovascular safety of celecoxib with traditional NSAID therapy in the setting of the European Union healthcare system.

Methods and analysis

SCOT is a large streamlined safety study conducted in Scotland, England, Denmark and the Netherlands using the Prospective Randomised Open Blinded Endpoint design. Patients aged over 60 years with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, free from established cardiovascular disease and requiring chronic NSAID therapy, are randomised to celecoxib or their previous traditional NSAID. They are then followed up for events by record-linkage within their normal healthcare setting. The hypothesis is non-inferiority with a confidence limit of 1.4. The primary endpoint is the first occurrence of hospitalisation or death for the Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) cardiovascular endpoint of non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or cardiovascular death. Secondary endpoints are (1) first hospitalisation or death for upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications (bleeding, perforation or obstruction); (2) first occurrence of hospitalised upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications or APTC endpoint; (3) first hospitalisation for heart failure; (4) first hospitalisation for APTC endpoint plus heart failure; (5) all-cause mortality and (6) first hospitalisation for new or worsening renal failure.

Ethics and dissemination

SCOT has been approved by the relevant ethics committees. The trial results will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Clinical trials registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00447759).

Keywords: Therapeutics

Article summary.

Article focus

The Standard care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT) compares the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of a strategy of celecoxib therapy and a strategy of traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis aged over 60 years without a history of cardiovascular disease.

Key messages

SCOT is a prospective randomised trial comparing celecoxib with traditional NSAIDs in patients with arthritis without a history of cardiovascular disease.

The cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs is an important issue where more evidence is required to guide practice.

SCOT uses electronic record-linkage to collect data on endpoints.

Strengths and limitations of this study

SCOT is a prospective randomised trial in a population of patients who take NSAIDs in the long term and are, therefore, representative of patients who might be at risk from NSAID therapy. SCOT is a streamlined safety trial with good external validity as it is conducted in the normal care setting. The limitations of the study include the need to extrapolate from the results to guide therapy in younger patients and in patients without a history of using NSAIDS and the lack of traditional study follow-up visits, although it has been shown that record-linkage can be used effectively in trial follow-up to detect events.

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced gastrointestinal toxicity is one of the most common serious drug adverse events requiring hospitalisation.1 Upper gastrointestinal complications result in considerable morbidity and mortality. The cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) selective NSAIDs gained popularity based on evidence that they are associated with a lower incidence of ulcer-related upper gastrointestinal tract complications compared with traditional non-selective NSAID therapy. However, the withdrawal of rofecoxib2 due to cardiovascular toxicity and the suggestion that most NSAIDs are probably associated with increased cardiovascular adverse events when compared with placebo3 have led to the need for further prospective studies on the safety of other COX-2 inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs.

The cardiovascular safety profile of COX-2 inhibitors was brought into question following the results of two placebo-controlled studies designed to test the hypothesis that the COX-2 inhibitors rofecoxib and celecoxib might prevent colorectal adenomas and colorectal tumours. The Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx Trial randomised patients with a history of colorectal adenomas to rofecoxib 25 mg or placebo and reported an excess of cardiovascular thrombotic events in the group treated with rofecoxib.4 The Prevention of Sporadic Colorectal Adenomas with Celecoxib (APC) Trial randomised patients with previous colorectal adenomas to celecoxib 400 mg twice daily, celecoxib 200 mg twice daily or placebo and reported a dose-related increase in the risk of cardiovascular events in the celecoxib groups.5 6 However, the Prevention of Colorectal Sporadic Adenomatous Polyps (PreSAP) Trial did not show a significant increase in cardiovascular events with celecoxib 400 mg given once per day versus placebo in patients with previous colorectal adenomas.7 In the Alzheimer's Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT), which was stopped early due to the findings of the APC trial, there was a suggestion of an increased risk of cardiovascular events with naproxen but not celecoxib compared with placebo, although this study was underpowered, and the cardiovascular results must therefore be interpreted with caution. In a later meta-analysis of six randomised double-blind placebo controlled trials of celecoxib in non-arthritis conditions, which included analysis of the APC, PreSAP and ADAPT studies and three other smaller studies (MA27, The Diabetic Macular Edema Trial and the Celecoxib/Selenium Trial), there was no evidence of increased cardiovascular risk with celecoxib in low-risk patients but there was a dose-dependent increase in cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients.8

In the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term programme, which compared cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib 60 or 90 mg daily and diclofenac 150 mg daily in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, the rates of thrombotic cardiovascular events were similar in patients randomised to either drug.9

In trials of celecoxib versus traditional NSAIDs, no evidence of increased cardiovascular toxicity has been seen.10 In large observational studies, celecoxib has not been found to be associated with increased cardiovascular risk versus other NSAIDs11 or non-use.12 13 At present, much of the available data comes from observational studies and while it seems clear that rofecoxib increased cardiovascular risk, many traditional NSAIDs may also pose considerable risk.3 11 14–16

The recent Celecoxib versus Omeprazole and Diclofenac in patients with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid arthritis study found that celecoxib was associated with a lower incidence of clinically significant upper or lower gastrointestinal events than the combination of diclofenac and omeprazole, adding further evidence to the improved gastrointestinal safety of COX-2 inhibitors compared with non-selective NSAIDs.17

Against this background of conflicting data, the overall risk-benefit balance of celecoxib versus traditional NSAIDs needs to be better clarified in a prospective trial design. This paper describes the design and rationale for The Standard care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT), which is a prospective trial randomising patients without a history of cardiovascular disease to celecoxib or traditional NSAID and measuring cardiovascular outcomes that is expected to report in 2014. This trial, which started recruiting in 2008, is a large streamlined safety study of celecoxib versus traditional NSAIDs in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis that aims to address the relative cardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of the two treatment strategies in a real-world setting.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

Overall trial design

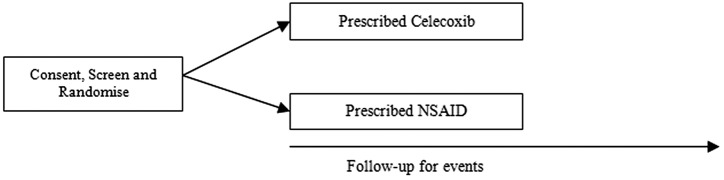

SCOT is an active comparator, streamlined clinical trial with a Prospective, Randomised, Open label, Blinded Endpoint evaluation (PROBE) design.18 It aims to compare the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of continuing with current traditional NSAID therapy versus switching to celecoxib therapy in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. After randomisation to celecoxib or continuation of their current traditional NSAID therapy, subjects are followed up for an average of 2 years for predefined cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal events and mortality (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Current Standard care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial design.

Study population

The European Medicines Agency requested that the trial population should include patients from at least two European Member States. The trial is being conducted in the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands. Patients over the age of 60 years, who are free from cardiovascular disease and are taking chronic NSAID therapy for osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, are included in the study. The trial inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in boxes 1 and 2, respectively.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria.

Age 60 or over.

Male and female subjects.

Chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use (≥90 days or at least three filled prescriptions in the last year).

Subjects who, in the opinion of the recruiting physician, have a licensed indication for chronic non-selective NSAID or celecoxib therapy (osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis).

Subjects who, in the opinion of the study site coordinator, are eligible for treatment (with reference to the summary of product characteristics) with either celecoxib or an alternative traditional non-selective NSAID. In particular, these subjects must be free from established cardiovascular disease (established ischaemic heart disease (IHD), heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease).

Subjects who are willing to give permission for their paper and electronic medical records and prescribing data to be accessed and abstracted by trial investigators.

Subjects who are willing to be contacted and interviewed by trial investigators, should the need arise for adverse event assessment, etc.

For the avoidance of doubt, there are no other specific comorbidities or concurrent drug therapies (including aspirin) that are contraindicated.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

Established cardiovascular disease including IHD such as myocardial infarction, angina or acute coronary syndrome, cerebrovascular disease such as a cerebrovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, established peripheral vascular disease and moderate or severe heart failure.

Subject currently taking a COX-2 selective NSAID (celecoxib or etoricoxib), or having received one of the therapies within 90 days of screening.

Presence of a life-threatening comorbidity (investigator opinion).

Presence of clinically important renal or hepatic disease (investigator opinion).

Subjects whose behaviour or lifestyle would render them less likely to comply with study medication (ie, alcoholism, substance misuse, debilitating psychiatric conditions or inability to provide informed consent).

Subjects with known or suspected allergy to celecoxib or NSAIDs including aspirin.

Subjects with known hypersensitivity to sulfonamide antibiotics.

Subjects with active peptic ulceration or gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

Subjects scheduled to have arthritis surgery likely to modify their need for pain relief within the next year.

Subjects currently participating in another clinical trial or who have been in a trial in the previous 3 months.

Recruitment and randomisation of participants

Potentially suitable patients are identified from general practice populations. Written informed consent is obtained from participants. The research nurse records baseline variables, takes blood and urine for baseline biochemistry and haematology and records the medical history. Blood samples are analysed at the local health service laboratory according to usual practice. Serum for future analyses and blood for future genetic analyses are stored by regional centres. Subjects who have given informed consent and meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria are randomised to receive celecoxib or to continue on their usual traditional NSAID therapy. Randomisation is performed by contacting a central randomisation facility based at the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow by telephone or via a web-based service.

Stratification of randomisation

Prior to the start of the study, a group of general practitioners’ databases in Scotland and the centralised dispensing database in Denmark were screened to identify the distribution of usage of different NSAIDs. On this basis, each NSAID with a frequency of usage >12% (ibuprofen and diclofenac) was assigned its own stratum. Other NSAIDs were pooled into a single stratum for the purpose of randomisation. The allocated therapy is prescribed using the normal health service prescription form. Thus, therapy is provided to patients in an open-label fashion in order to mimic normal care as closely as possible.

After randomisation, a health service prescription is issued for the randomised drug and the patient's case records and computer file are marked to show that they are participating in SCOT. Repeat prescriptions are issued according to normal clinical practice and patients take their medication according to clinical need. This method is ‘naturalistic’ in that it most closely mimics the real world of NSAID use.

Trial treatments

The trial treatments are either celecoxib (Celebrex) or any other licensed, non-selective traditional NSAID listed in the British National Formulary section 10.1.1 (ibuprofen, aceclofenac, acemetacin, dexibuprofen, dexketoprofen, diclofenac sodium, diflunisal, etodolac, fenbufen, fenoprofen, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indometacin, ketoprofen, mefenamic acid, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, piroxicam, sulindac, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid and Arthrotec (diclofenac plus misoprostol)).

Celecoxib is prescribed at standard licensed doses of up to 200 mg twice daily—the dose is adjusted as necessary up to this maximum limit to provide adequate symptomatic relief. Other NSAIDs are continued at their standard licensed doses and again, the dose may be adjusted as necessary to control symptoms.

Compliance

Study medication prescriptions are recorded on practice computer systems. Compliance is measured as the number of prescription doses prescribed divided by the number of days between prescriptions averaged over the time in the trial.

Discontinuation of randomised therapy

If a period of 56 days elapses from the estimated end of the last written prescription or if a prescription is written for a traditional NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor other than that allocated at the time of randomisation, it is confirmed whether the patient has discontinued therapy and, if appropriate, the reason for study drug discontinuation is recorded.

Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications are also recorded. Of particular interest are prescriptions for aspirin, ulcer healing drugs and antihypertensive drugs.

Rescue medication

Efficacy

Patients who experience the onset of inadequate therapeutic efficacy may be up-titrated in dose as per normal clinical practice. Such dose escalations are tracked. Additional rescue medication may be prescribed in order that the patient continues on randomised therapy. These rescue medications may include paracetamol (acetaminophen), opiates such as codeine, dihydrocodeine, tramadol, etc, nefopam, low dose antidepressant therapy and other recognised analgesic augmenting therapies.

Tolerability

Patients who experience the onset of symptoms of upper gastrointestinal discomfort, dyspepsia or heartburn may be prescribed antacid therapy or ulcer healing therapy at the discretion of their primary care physician. Study site coordinators report such events as treatment-related adverse events and specify if they lead to discontinuation of randomised study treatment.

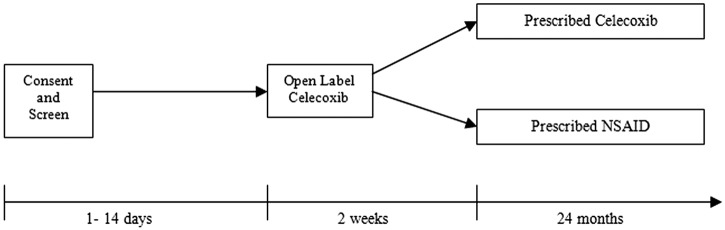

Original study design with a celecoxib run-in period (2008–2010 prior to protocol amendment)

In the original trial design (for patients entering the study up to between April and August 2010 depending on the study site), 3962 subjects underwent a celecoxib run-in period prior to randomisation and 2545 subjects were subsequently randomised. The celecoxib run-in was carried out in all patients completing screening for the study. They were asked to discontinue their current NSAID and enter a 2-week (14±7 days) open-label run-in of treatment with celecoxib as two to four 100 mg tablets taken daily in single or divided doses (figure 2). During the run-in period, the dose of celecoxib was titrated to achieve equivalent pain control to their previous NSAID therapy. At the end of this period, subjects who had taken at least one dose of celecoxib and who did not express a strong preference for either their previous treatment or celecoxib were eligible for randomisation. Preference was determined by the patient response to a questionnaire:

Figure 2.

Original Standard care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial design (including 2-week celecoxib run-in period).

Which statement do you agree with?

My previous painkiller was much better than celecoxib

My previous painkiller was somewhat better than celecoxib

My previous painkiller and celecoxib were the same

Celecoxib was somewhat better than my previous painkiller

Celecoxib was much better than my previous painkiller

Only subjects who responded with answers 2, 3 or 4 were eligible for randomisation. This resulted in 1417 subjects being excluded using this run-in period.

This open-label celecoxib run-in period was originally included in the design of SCOT because a major problem with previous randomised trials of NSAID toxicity had been dropout from randomised treatment during the trial. For example, in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial, only 60% of subjects completed the trial and 31–37% of subjects withdrew from randomised therapy.19 In the CLASS study, less than 50% of those randomised completed the study and there was differential dropout between the two treatment arms.20 A similar trial run-in phase was used in the Heart Protection Study.21 It was hoped that by having a celecoxib run-in period, dropouts after randomisation would be avoided. However, after a review of the data on the level of dropouts after the first few years of the trial, it was clear that the celecoxib run-in period was resulting in different rates of randomisation in different centres with hardly any being excluded in some centres and a high proportion being excluded in others. For this reason, the protocol was amended to remove the run-in period and to perform randomisation on the day of screening if the subject was eligible. This amendment was implemented in each region on different dates but was completed by September 2010. Since then, up to October 2012, around 3500 further patients were randomised without a run-in period. We have since formally evaluated the influence of the presence or absence of the celecoxib run-in period on study dropout rates and found no significant difference (adjusted OR for dropout at 180 days in patients with the celecoxib run-in period was 1.28 (95% CI 0.76 to 2.14).22

Trial endpoints

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is the first occurrence of hospitalisation or death for the Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration cardiovascular endpoint of non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke or cardiovascular death.

The secondary and tertiary endpoints and further planned analyses are listed in box 3.

Box 3. Secondary and tertiary endpoints and further analyses.

Secondary endpoints

First occurrence of hospitalisation or death for upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications (bleeding, perforation or obstruction).

First occurrence of hospitalised upper gastrointestinal ulcer complications or Anti-Platelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) endpoint.

First hospitalisation for heart failure.

First occurrence of hospitalisation for APTC endpoint plus heart failure.

All cause mortality.

First hospitalisation for new or worsening renal failure.

Tertiary endpoints

First occurrence of hospitalisation or death for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction not due to ulcers.

First occurrence of hospitalisation or death for lower gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction.

First occurrence of hospitalisation or death for all episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction.

Further planned analyses

Myocardial infarction as a whole and as the components of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction and non ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Non-fatal stroke.

Cardiovascular death.

-

Analyses of GI subcomponents

Hospitalisation or death for all episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding;

Hospitalisation or death for all episodes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding and

Hospitalisation or death for all episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding.

All uncomplicated upper gastrointestinal ulcers detected during the study.

All upper gastrointestinal ulcers (complicated and uncomplicated) detected during the study.

New prescription for ulcer healing drugs.

All hospitalisations.

Assessment of study endpoints, adverse events and serious adverse events

The principal mode of collection of study endpoints, adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) in SCOT is by record-linkage from national population healthcare databases. Record-linkage retrieves electronic records of hospitalisations and deaths for individual patients within the study from central databases. Hospitalisation discharge diagnoses are coded and causes of death are reported. Any events of particular interest (potential study endpoints) are investigated further and confirmed by retrieving the original case records. Record-linkage has previously been demonstrated to be highly effective in the follow-up of patients for study events.23 Any treatment-related adverse events and SAEs detected and reported by research staff or physicians manually are also collected and investigated.

Mortality data by record-linkage

Mortality and certified cause-specific mortality are retrieved from national mortality record systems by record-linkage at approximately 3 monthly intervals.

Morbidity data by record-linkage

Hospitalisations are retrieved by record-linkage from national systems at approximately 3 monthly intervals.

Data abstraction for endpoint adjudication

For each death, and for each hospitalisation that is a potential endpoint, primary care and secondary care records and, if appropriate, full death certification data are retrieved. Diagnostic validation forms are filled in to supplement scanned images of original case records relating to the endpoints in question. The scanned images of case records and the data validation forms are collated. Any record of randomised treatment is removed before these collated documents are passed to the relevant (cardiovascular or gastrointestinal) endpoint committee for adjudication as to the hospital diagnosis or the cause of death. This is the PROBE design, which is similar to the design of the Anglo Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial.24

Adjudication of endpoints

Endpoint data are adjudicated by two independent endpoint committees, one for cardiovascular endpoints (also adjudicated in heart failure, renal and death endpoints) and one for gastrointestinal endpoints. These committees are blinded to randomised treatment and have due regard of the published consensus diagnostic criteria for myocardial infarction,25 stroke,26 vascular death, ulcer-related upper gastrointestinal hospitalisations or death, heart failure27 and renal failure.28 29

Adverse events

All observed or volunteered adverse events that are considered to be serious or related to randomised study treatment, regardless of the treatment group or suspected causal relationship to the investigational product(s), are recorded on the adverse event pages of the electronic case report form. Adverse events are defined as abnormal test findings, clinically significant symptoms and signs, changes in physical examination findings or hypersensitivity. An SAE or a serious adverse drug reaction is any untoward medical occurrence at any dose that: results in death, is life-threatening (immediate risk of death), requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or results in a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

For these adverse events, further information is obtained to determine the outcome of the adverse event and to confirm whether it meets the criteria for classification as an SAE requiring immediate notification to the sponsor. Physicians assess causality, and the expectedness of any SAE thought to be related to a study drug, on the web portal. Follow-up of SAEs continues until the event has resolved or the patient has died. In this study, primary and secondary study endpoints and their associated symptoms and laboratory abnormalities are not reported as Suspected Unexpected Serious Adverse Drug Reactions. Further, adverse events that are neither considered to be serious nor related to randomised treatment are not reported.

Data analysis/statistical method

Sample size determination

Originally, the study was powered at 90% to exclude a 30% poorer outcome on celecoxib compared with traditional NSAIDs (HR=1.3) in the primary endpoint with a non-inferiority analysis between the two treatment strategies. However, owing to slower than expected recruitment and lower than expected event rates, the trial steering committee made the decision to revise the power of the study to 80% and the non-inferiority limit to 1.4 in October 2011.

The statistical method to be used will involve a stratified Cox proportional hazards model including the randomisation strata and the randomised treatment group as covariates. Statistical significance for the treatment differences will be based on the Wald statistics and on two-sided 95% CIs for the estimated HR comparing celecoxib to non-selective NSAIDs. The original power calculations suggested that, for an average duration of 2 years’ exposure to treatment with a 30% non-inferiority limit and an NSAID-exposed CV event rate of 2% per year, the study would require 6841 subjects in each treatment group or 13 682 subjects in total and 611 patients with endpoints (based on an intention-to-treat analysis). Since an on-treatment analysis would result in reduced follow-up that was difficult to predict a priori, follow-up would be continued until 611 endpoints were identified in the per-protocol population. Following the revision to the power calculation made in 2011 (power 80%, non-inferiority limit 1.4), the number of primary endpoints required to achieve adequate power in the per-protocol population decreased to 277.

Primary analysis

A full Statistical Analysis Plan has been developed. The first analysis to be carried out will be a non-inferiority analysis of the primary outcome based on the per-protocol population (those subjects remaining on randomised therapy) with a supporting non-inferiority analysis based on the intention-to-treat population. A patient will be considered to remain on the randomised therapy until a period of 56 days following the last recorded prescription of the medication allocated at randomisation plus 28 calendar days.

Thus, the per-protocol analysis will censor subjects after:

Discontinuation from original randomised therapy (defined as 84 days after the day of the last recorded prescription);

First primary study endpoint and

Withdrawal of consent.

If non-inferiority is demonstrated, a superiority analysis will be carried out based on the intention-to-treat population.

Sensitivity analysis

A prospective sensitivity analysis will be performed, adding a 90-day period to the per-protocol period (or end of the study), to ensure that withdrawal or crossover is not a presage of disease. This will be performed for both primary and secondary endpoints.

Subgroup analyses and prognostic factors

Subgroup analyses will be conducted comparing celecoxib treatment with each of the individual non-selective NSAID treatments allocated at randomisation. In addition, subgroup analyses will be carried out for each of the baseline covariates described below that are significant predictors of the primary endpoint in a Cox regression model including that variable alone plus the stratification categorical variable.

Baseline covariates include age, sex, baseline blood pressure, baseline total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterols, body mass index, smoking status, prior upper gastrointestinal bleed or perforation, history of peptic ulcer, Helicobacter pylori serology status at baseline, diabetes, social deprivation category, use of systemic (not inhaled) steroids at entry, indication for NSAID, that is, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis diagnosis, randomised therapy and aspirin use.

Ethics and dissemination

Steering committee and independent data monitoring committee

A steering committee oversees the conduct of the trial and an independent data monitoring committee receives unblinded data and has the power to recommend to the steering committee modifications to the study conduct, including early discontinuation of the study, based on a risk/benefit assessment of the study data.

Study sponsorship: monitoring, audit, quality control and quality assurance

The University of Dundee is the study sponsor that supervises the monitoring and undertakes the quality assurance of the study.

Legal and ethical issues

The trial has been approved by the UK Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (Reference number: 2006-005735-24) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (Reference number: 07/MRE00/9). It is also approved by the relevant authorities in Denmark and the Netherlands. It is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Reference number: NCT00447759). The trial is performed in accordance with the protocol, International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, ISPE Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice guidance30 and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws.

Dissemination

The results of the trial will be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Discussion

The methodology of SCOT differs from many traditional trials in that follow-up is largely electronic, using record-linkage techniques, and treatments are prescribed within the usual healthcare setting. Such a design means that the trial more closely mimics normal care. There have been a number of publications of meta-analyses of the cardiovascular risk-benefit of celecoxib compared with NSAIDs.31–33 Most of them showed that there was no increase in cardiovascular risk in patients receiving celecoxib compared with traditional NSAIDs. Alongside the current trial, SCOT, a more traditional trial is ongoing in the USA—The Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION) trial.34 35 It is a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study of cardiovascular safety in osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis patients with, or at high risk of, cardiovascular disease comparing celecoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen.

Traditional trials have good internal validity but less external validity. A large streamlined safety trial is expected to have good external validity. However, such a trial becomes more observational with time and internal validity becomes less reliable. The results of PRECISION and SCOT are likely to be available by around 2014, and we believe that the results will inform clinical practice in a more reliable way than previous studies of the cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs. We believe that naturalistic trials such as SCOT will be essential in shaping healthcare policy in the future.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: The manuscript was written by the authors on behalf of the SCOT Study Group collaborators as listed below, many of whom provided critical input to the manuscript. Other SCOT Study Group collaborators: Steering Committee—Jesper Hallas, John Webster, David Reid, Stuart Ralston, Matthew Walters, FD Richard Hobbs, Sir Lewis Ritchie, Mark Davis, Susana Perez-Gutthann, Frank Ruschitzka, James Scheiman, Evelyn Findlay, John McMurray, Brendan Delaney and Diederick Grobbee. Independent Data and Statistical Centre. Sharon Kean (IT and data management), Nicola Greenlaw and Michele Robertson (Biostatistics) Independent Data Monitoring Committee. Kim Fox (Chair), Gordon Murray, Frank Murray. Endpoint Adjudication Committees. Cardiovascular: John McMurray (Chair), Pardeep Jhund, Mark Petrie, Michael MacDonald. Gastrointestinal: James Scheiman (Chair), John Dillon, Jane Moeller, Angel Lanas.

Contributors: TM, IF and CJH conceived the idea for the study and were responsible for the initial design of the study. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. The initial draft of the manuscript was created by LW and IM and circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. TM is the Chief Investigator of SCOT. TM, IF and CJH are members of the Executive and Steering Committees of SCOT. IM is a member of the Steering Committee of SCOT. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study took place as an academic study, grant-funded by Pfizer as an Investigator Initiated Research Grant, under a full legal agreement with Pfizer, with the University of Dundee being the study sponsor. The study was designed by the trial executive committee (Professor Tom MacDonald, Professor Ian Ford and Professor Chris Hawkey). The sponsor (University of Dundee) and the trial steering committee are primarily responsible for data collection, trial management, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report and submission of the report for publication. Pfizer has provided funding for the SCOT study but has no authority over the above activities.

Competing interests: IM and TM have previously had part of their university salary reimbursed to the University by Pfizer in connection with SCOT. In the last 5 years, TM has received honoraria for lectures and consulting from NiCox, Novartis and Astra Zeneca in relation to NSAID therapies and from other companies regarding other therapeutic areas. MEMO holds research grants from Novartis, Pfizer, Ipsen & Menarini. IF and CJH have received research funding from Pfizer in relation to the conduct of SCOT.

Ethics approval: The trial has been approved by the UK Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) (Reference number: 2006-005735-24) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (Reference number: 07/MRE00/9). It is also approved by the relevant authorities in Denmark and the Netherlands.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Jesper Hallas, John Webster, David Reid, Stuart Ralston, Matthew Walters, FD Richard Hobbs, Sir Lewis Ritchie, Mark Davis, Susana Perez-Gutthann, Frank Ruschitzka, James Scheiman, Evelyn Findlay, John McMurray, Brendan Delaney, Diederick Grobbee, Sharon Kean, Nicola Greenlaw, Michele Robertson, Kim Fox, Gordon Murray, Frank Murray, John McMurray, Pardeep Jhund, Mark Petrie, Michael MacDonald, James Scheiman, John Dillon, Jane Moeller, and Angel Lanas

References

- 1.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://www.itqb.unl.pt/~ccr/quimicaemlinha/PDF%20files/VIOXXmerck.pdf (accessed 25 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J, et al. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2006;332:1302–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1092–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) Study Investigators. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1071–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med 2006;355:873–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak Jet al. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med 2006;355:885–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, et al. Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: the cross trial safety analysis. Circulation 2008;117:2104–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon CP, Curtis SP, Fitzgerald GA, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) programme: a randomised comparison. Lancet 2006;368:1771–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White WB, Faich G, Borer JS, et al. Cardiovascular Thrombotic Events in Arthritis Trials of the Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitor Celecoxib. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:411–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez LA Garcia, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P. Role of dose potency in the prediction of risk of myocardial infarction associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1628–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez-Diaz S, Varas-Lorenzo C, Rodriguez LA Garcia. Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006;98:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA 2006;296:1633–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:141–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fosbol EL, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and death associated with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among healthy individuals: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;85:190–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:c7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan FKL, Lanas A, Scheiman J, et al. Celecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:173–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansson L, Hedner T, Dahlof B. Prospective randomised open blinded end-point (PROBE) study. A novel design for intervention trials. Prospective Randomised Open Blinded End-Point. Blood Press 1992;1:113–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farkouh ME, Kirshner H, Harrington RA, et al. Comparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), cardiovascular outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:675–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib long-term arthritis safety study. JAMA 2000;284:1247–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7–2212114036 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei L, MacDonald TM, on behalf of the SCOT Study Group Collaborators Drop-out rates in patients with and without screening period in the SCOT trial. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(Suppl 3):87 abstract22095760 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford I, Murray H, Shepherd J, et al. Long-term follow-up of the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1477–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sever PS, Dahlof B, Poulter NR, et al. Rationale, design, methods and baseline demography of participants of the Anglo-scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial. ASCOT investigators. J Hypertens 2001:1139–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams HP, Jr, Adams RJ, Brott T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the stroke council of the American stroke association. Stroke 2003;34:1056–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swedberg K, Cleland J, Dargie H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1115–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey AS. Clinical practice. Non-diabetic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perazella MA. Drug-induced renal failure: update on new medications and unique mechanisms of nephrotoxicity. Am J Med Sci 2003;325:349–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE) Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP). 2007. http://www.pharmacoepi.org/resources/guidelines_08027.cfm (accessed 1 Oct 2012)

- 31.White WB, West CR, Borer JS, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events in patients receiving celecoxib: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:91–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore RA, Derry S, Makinson GT, et al. Tolerability and adverse events in clinical trials of celecoxib in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of information from company clinical trial reports. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R644–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varas-Lorenzo C, Maguire A, Castellsague J, et al. Quantitative assessment of the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk-benefit of celecoxib compared to individual NSAIDs at the population level. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:366–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker MC, Wang TH, Wisniewski L, et al. Rationale, design, and governance of Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen Or Naproxen (PRECISION), a cardiovascular end point trial of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents in patients with arthritis. Am Heart J 2009;157:606–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00346216 (accessed 25 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.