Abstract

Objectives

An initial stratification of acute whiplash patients into seven risk-strata in relation to 1-year work disability as primary outcome is presented.

Design

The design was an observational prospective study of risk factors embedded in a randomised controlled study.

Setting

Acute whiplash patients from units, general practitioners in four Danish counties were referred to two research centres.

Participants

During a 2-year inclusion period, acute consecutive whiplash-injured (age 18–70 years, rear-end or frontal-end car accident and WAD (whiplash-associated disorders) grades I–III, symptoms within 72 h, examination prior to 10 days postinjury, capable of written/spoken Danish, without other injuries/fractures, pre-existing significant somatic/psychiatric disorder, drug/alcohol abuse and previous significant pain/headache). 688 (438 women and 250 men) participants were interviewed and examined by a study nurse after 5 days; 605 were completed after 1 year. A risk score which included items of initial neck pain/headache intensity, a number of non-painful complaints and active neck mobility was applied. The primary outcome parameter was 1-year work disability.

Results

The risk score and number of sick-listing days were related (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.0001). In stratum 1, less than 4%, but in stratum 7, 68% were work-disabled after 1 year. Early work assessment (p<0.0001), impact of the event questionnaire (p<0.0006), psychophysical pain measures being McGill pain questionnaire parameters (p<0.0001), pressure pain algometry (p<0.0001) and palpation (p<0.0001) showed a significant relationship with risk stratification.

Analysis

Findings confirm previous studies reporting intense neck pain/headache and distress as predictors for work disability after whiplash. Neck-mobility was a strong predictor in this study; however, it was a more inconsistent predictor in other studies.

Conclusions

Application of the risk assessment score and use of the risk strata system may be beneficial in future studies and may be considered as a valuable tool to assess return-to-work following injuries; however, further studies are needed.

Keywords: Trauma Management, Accident & Emergency Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

In an observational study of acute whiplash patients performed earlier, we identified risk factors which provided a risk assessment score.

The risk assessment score was applied in a new 1-year longitudinal multicentre cohort study of acute whiplash patients with a main outcome parameter of a 1-year work disability.

Key messages

Significant relation was found between the risk assessment score and 1-year work disability. Stratification early after whiplash injury into seven risk strata was furthermore supported by other findings concerning psychological, social, work-related and psychophysical pain measures.

The Risk Assesment Score may be considered a valuable tool for assessment of work disability in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

Initially, risk factors were identified in an observational study and then applied and validated in this multicentre study. To further validate findings, other researchers should apply the risk assessment score and the seven strata stratification system on other populations for further external validation.

Introduction

Chronic pain represents a major problem in the Western world with approximately 20% of the adult population suffering from chronic pain. Our ability to deal with these chronic pain conditions is insufficient as it is in various other areas, such as traumatic injuries and pain following surgery or other medical procedures. Identifying patients at risk of developing chronic pain is a prerequisite for establishment of prophylactic initiatives.

When discussing pain following surgery, it has been demonstrated that prior pain intensity, the duration of pain, the type of surgery, the nerve damage during surgery as well as psychological factors, information and the setting and the genetic endowment are of significant importance with respect to the future development and persistence of chronic pain.1–5 Also, regarding musculoskeletal pain conditions, such as headache,6 cervical sprains7 and low back pain,8 there is an interest in exploring the potential risk factors aligned with persistent pain. The specific type of distortion of the cervical spine, stemming from a so-called whiplash injury, in which the neck spine is exposed to a forced extension-flexion trauma, is often followed by a late pain state known as whiplash-associated disorders (WAD).9 10

These injuries may be associated with a reduction of the pain threshold to mechanical pressure in the neck muscles,11 12 a reduction of nociceptive flexion reflexes13 and an expansion of cutaneously referred pain symptoms following the infusion of hypertonic saline into the muscles both at the injury site and in areas remote from the injury site.14 These findings suggest generalised hyper-excitability following a whiplash injury, which resolves in patients recovering after injury but persists in patients with ongoing symptoms.2 11 15–17

Whiplash-associated disorders fall into the categories O–IV according to the Quebec WAD grading.9 In a previous observational study, we found that a risk score based on neck pain, headache, the number of non-painful symptoms and reduced neck mobility was associated with a marked risk of reduced recovery.18 Based on these observations, the objective of this study was to test a stratified risk assessment scoring system for predicting long-term sequelae after a whiplash injury. A risk index was developed in a previous cohort and the predictive capability of seven risk strata tested.18 19 In the present study, we test whether the seven risk strata are useful for prediction of outcome in that second sample. In addition, differences in psychological and social factors across the strata are described.

Materials and methods

Study overview

A risk stratification index based on the measures of intensity of neck pain and headache, cervical range of motion (CROM) and number of non-painful complaints was developed in a previous sample of whiplash injured seen in an emergency care unit.18 Using a pragmatic approach, seven risk strata were formed and this stratification was strongly associated with outcome.19

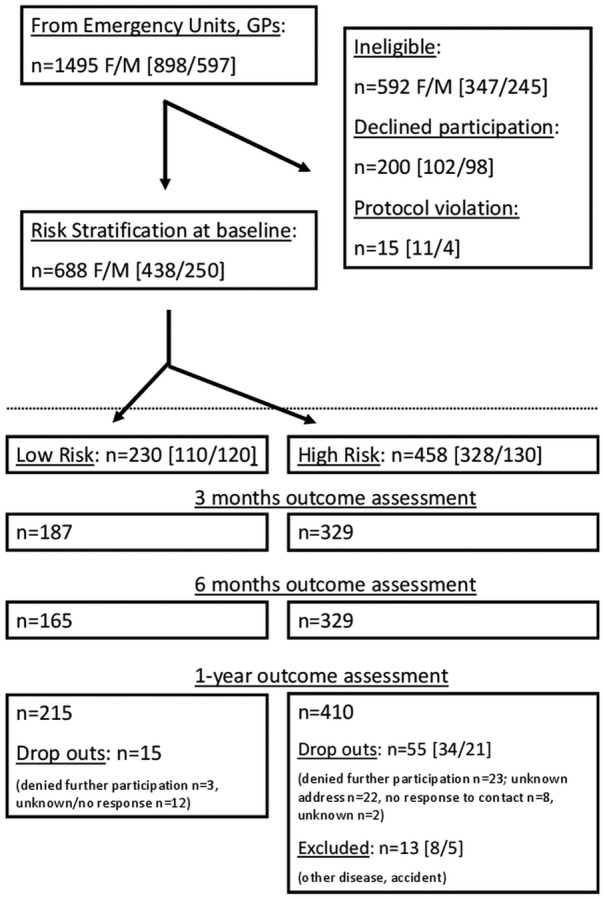

In the present study, these risk strata are tested in another sample enrolled between May 2001 and June 2003. The study concludes a secondary analysis of two parallel randomised controlled trials.20 21 Patients were enrolled within 10 days of a whiplash injury. Those with a low-risk stratification index score were randomised to either oral or written advice to act as usual,20 whereas patients with high-risk scores were randomised to immobilisation (semi-rigid neck collar), active mobilisation (McKenzie technique) or an oral recommendation to act as usual21 (figure 1). The oral and written advices were delivered at the day of inclusion. The neck collar and active mobilisation interventions involved contact with a physical therapist for a maximum of 6 weeks. Details about the interventions are reported elsewhere.20 21 No significant differences in treatment effects were demonstrated and participants are therefore considered in one cohort for the present study. The study was approved by the local ethical committees (The Scientific Committee for The Counties of Vejle and Funen, Project number 20000268) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki II Declaration.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the whiplash study.

Study population

The cohort has been previously described.11 20–22 In short, persons with complaints from the neck and/or shoulder girdle (WAD grade I–III) seeking care at an emergency unit or a general practitioner within 72 h after a motor vehicle collision were potential participants. Other inclusion criteria were the following: age 18–70 years, exposure to a rear-end or frontal-end car accident and that an examination could be performed within 10 days after the injury. Exclusion criteria were inability to read and speak Danish, injuries with fractures or dislocations (WAD grade IV), additional trauma other than the whiplash injury, pre-existing significant somatic or psychiatric disease, known active alcohol or drug abuse and significant headache or neck pain (self-reported average pain during the preceding 6 months exceeding 2 on a 0–10 box scale, 0=no pain; 10=worst possible pain).

Risk Stratification Index measures

Pain: neck pain and headache since the collision were scored on an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (0=no pain; 10=worst imaginable pain).23 24

Non-painful complaints: participants were asked whether any of the 11 non-painful complaints (paresthesia, dizziness, vision disturbances, tinnitus, hyperacusis, dysphagia, fatigue, irritation, concentration disturbances, memory difficulties and sleep disturbances) had started or been markedly worse since the accident.

Active neck mobility: total CROM including flexion, extension, right and left lateral-flexion and right and left rotation was assessed with a CROM device as formerly described.22 25

Risk stratification was performed by combining scores on pain intensity, CROM and a number of non-painful complaints.19 Each factor was categorised and scored as follows.

The highest score of neck pain and headache was categorised into 0–2=0 points; 3–4=1 point; 5–8=4 points; 9–10=6 points.

Total active CROM was divided into: below 200°=10 points; 200–220=8 points; 221–240=6 points; 241–260=4 points; 261–280=2 points and above 280=0 points.

Number of non-painful complaints: 0–2=0 points; 3–5=1 point and 6–11=3 points.

The following stratification was made: stratum 1=0 points; stratum 2=1–3 points; stratum 3=4–6 points; stratum 4=7–9 points; stratum 5=10–12 points; stratum 6=13–15 points and stratum 7=16–19 points (see table 1 for overview).

Table 1.

The Danish whiplash study group risk assessment score

| The Danish whiplash study group risk assessment score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| CROM | >280 | 261–280 | 241–260 | 221–240 | 200–220 | <200 | |||||

| Neck/head VAS | 0–2 | 3–4 | 5–8 | 9–10 | |||||||

| Number of non-pain symptoms | 0–2 | 3–5 | 6–11 | ||||||||

| Stratum 1 | 0 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 2 | 1–3 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 3 | 4–6 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 4 | 7–9 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 5 | 10–12 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 6 | 13–15 points | ||||||||||

| Stratum 7 | 16–19 points | ||||||||||

CROM, cervical range of motion; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Outcome measures

Follow-up questionnaires were posted to participants after 3, 6 and 12 months. Beside data on sick leave, only 12 months’ follow-up was used for the present study.

The primary outcome measure

The primary outcome variable selected a priori was 1-year work disability, which was defined as: (1) sick leave> 3 months during the last 6 months; (2) work inability during the entire last month or (3) not working anymore because of the accident.18

The number of days on sick leave was computed by means of a completed diary (a patient log) and questionnaire data after 3, 6 and 12 months postinjury. Days with sick leave counted as full days and days with reduced working hours counted as half days of sick leave. If the patient could manage a full-time job but had changed functions after injury, it counted as full working hours. Patients who did not work prior to the injury (on leave, unemployed, disability pension, retired) were not considered in the calculated risk of 1-year work disability but were included in computation of the secondary outcome measures, which have been described elsewhere.20 21

Other outcome measures

Work-related factors: expected difficulties with work were measured by asking ‘How big a problem do you expect it to be to take care of your job/study 6 weeks from now?’ (0=no problem at all; 10=a very big problem, cannot work), and ‘How likely do you consider it that you will be working/studying 6 weeks from now?’ (0=very likely; 10=very unlikely). Self-rated physical work demands were registered asking: ‘How physically demanding do you consider your present/most recent job’ (0=not physically demanding at all; 10=very physically demanding).

Post-traumatic stress response was measured by means of the Impact of Event Scale (IES).26 A total sum-score was calculated from all 15 items of the scale. In addition, an intrusion score (sum of 7 items) and an avoidance score (sum of 8 items) were calculated.

Pressure algometry: the hand-held Algometer (Somedic Algometer type 2) was applied with a slope of 30 kpa/s and a probe area of 1.0 cm2; pressure pain-detection thresholds were measured in triplets, whereas pressure pain-tolerance thresholds were measured by one application of pressure only.11

Methodical muscle palpation was performed bilaterally at nine sites: (1) the anterior part of the temporal muscle, (2) the posterior part of the temporal muscle, (3) the masseter muscle, (4) the lateral pterygoid muscle, (5) the sternocleid at the mastoid insertion point, (6) the sternocleid at its middle belly, (7) the suboccipital muscle group, (8) the superior trapezius muscle and (9) the rhomboid muscle along the medial border of the scapula. At each palpation site, a pain score (0–4) was obtained11 27 with

0 Equalling neither pain nor reported tenderness;

1 Equalling complaints of mild pain but no facial contortion (grimace), flinch or withdrawal;

2 Equalling a moderate pain and degree of facial contortion (grimace) or flinch;

3 Equalling a severe pain and marked flinch or withdrawal and

4 Equalling unbearable pain and withdrawal without palpation.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were made with Stata V.12.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2010 for Windows. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for analysis of the strata. Parametric data with normal distribution or log normal distribution were presented within each risk stratum graph as mean±SEM values. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves are given for applied individual factors in the risk assessment score (see online supplementary figure S1), and sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative Likelihood ratios were computed for each stratum for 1-year work disability (refer to online supplementary table S2). Two-way analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were applied for testing eventual variability difference between centres for the clinical measures.

Variability: palpation, pressure algometry and cervical range of motion measurement were standardised at group meetings during the observation period to reduce eventual intertester and intratester variability.

Results

Details of the study population have been described previously; a flow chart is presented in figure 1.22 Briefly, a total of 1495 (F/M: 898/597) acute whiplash patients were contacted after being examined at the emergency units or by their general practitioners. A total of 688 eligible acute whiplash patients (F/M 443/252) gave informed written and verbal consent to participate. Of these, 30 were unemployed but considered capable of working before injury, and 10 were either retired or on disability pension and were not considered in primary but only secondary outcome measure (social factors are tabulated in ref 22).

Two hundred (F/M: 102/98) patients refused to participate. In total, 592 patients were not eligible, and 15 were excluded due to protocol violation (under-reporting of previous neck pain, visual analogue scale (VAS)>5 n=8; wrong initial group allocation in treatment study, n=7).

Risk strata

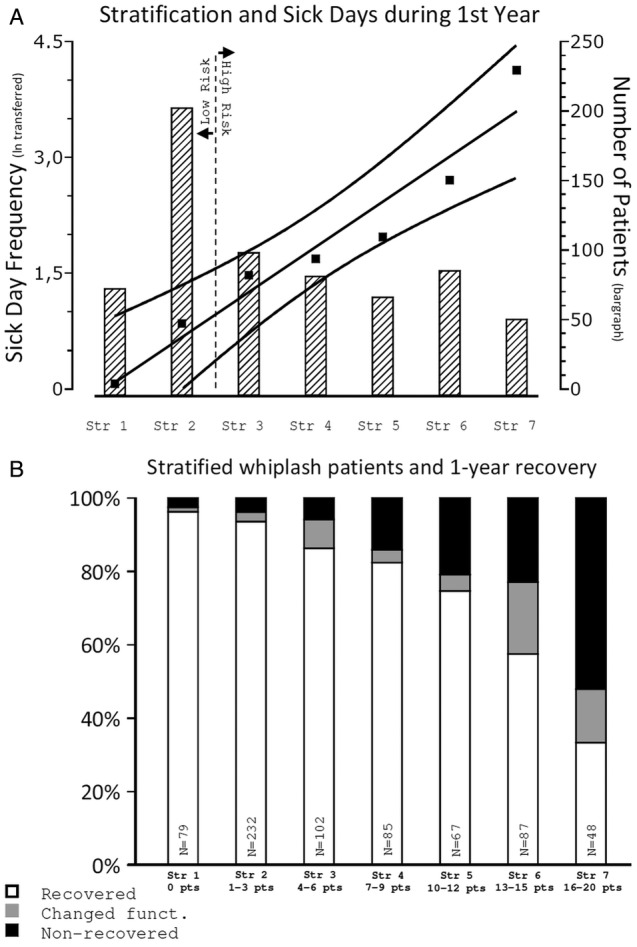

Figure 2A shows a log-linear relationship between the risk assessment score and the number of days being sick for acute whiplash patients.

Figure 2.

(A) Risk strata and the number of sick-listed days during the first year after whiplash injury. (B) One year recovery from whiplash injury in risk strata.

Figure 2B shows distribution in the risk strata after 1 year of patients (1) returning to work or (2) having reduced functional capacity in full-time jobs or (3) being work disabled. Although 96% had returned to work in stratum 1, only 32% of previous healthy whiplash-exposed in stratum 7 were back at work after 1 year (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.0001).

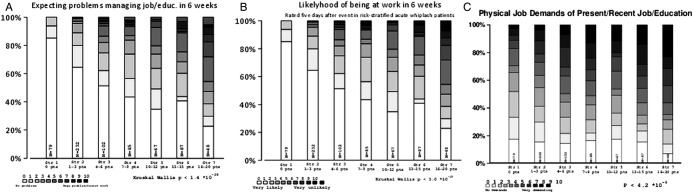

In figure 3A–C, the ability to perform work within 6 weeks and the ability to return to work within 6 weeks and the assessment of the physical demands of their present/recent job were rated after 5 median days on an NRS-11-point box scale. Job-related issues were increasingly severe in the higher risk stratum of the patient (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Initial numeric rating of work related issues in risk strata. (A) Expecting problems managing one's job/education in 6 weeks. (B) likelihood of being back to work/education in 6 weeks and, (C) evaluation of the physical job requirement of the current or most recent job/education.

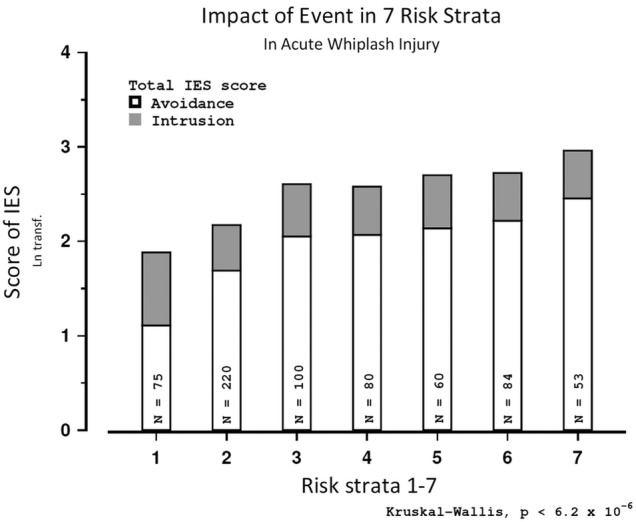

The components of the impact of event scale in figure 4 intrusion and avoidance and the total IES score were bar-graphed for each stratum. There was an increase in reported injury-related emotional distress in the risk strata (Kruskall-Wallis, p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

The impact of event scale with subscales of intrusion and avoidance shown in risk strata.

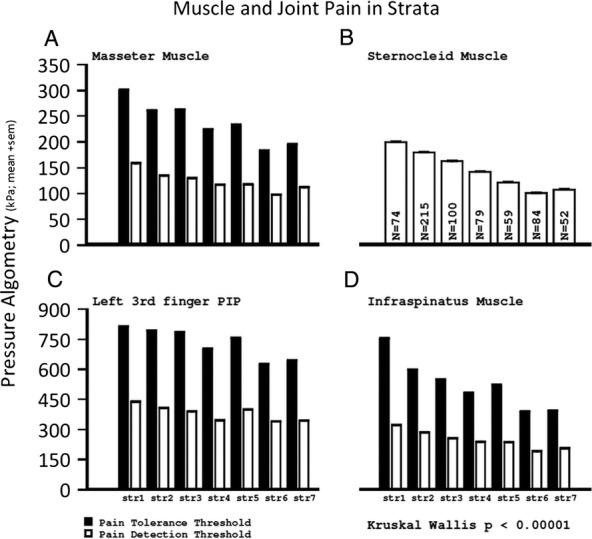

Figure 5A–D display the bar graphs of strata representing pressure algometry for both pain-detection thresholds and pain-tolerance thresholds for the muscles in the neck region: the masseter and the infraspinatus muscles and at a remote control site at the left third finger joint. All these psychophysical measures are differently distributed in the risk strata (Kruskall-Wallis , p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

(A) Pressure algometry in the neck and head and remote from injury in risk strata. (B) Pressure algometry in the neck and head and remote from injury in risk strata. (C) Pressure algometry in the neck and head and remote from injury in risk strata. PPT pressure pain tolerance threshold and PPDT pressure pain detection threshold (Kilo Pascal, Mean±SEM), (D) Pressure algometry in the neck and head and remote from injury in risk strata.

The total palpation score was similarly distributed and significantly different in risk strata (Kruskall-Wallis p<0.0001) with a score of 6 in stratum 1 and 24 in stratum 7 (refer to online supplementary figure S2).

The Copenhagen Neck Disability Index score after 1 year was significantly related to risk strata (Kruskall-Wallis , p<0.0001), and the 1-year 11-point box scores of shoulder–arm pain, and neck pain, headache and global pain were significantly related to risk strata (p<0.0001) as well as all McGill Pain Questionnaire derived pain-rating indices (PRI-T; PRI-S, PRI-A, PRI-E, PRI-M) and number of word count (Kruskall-Wallis, p<0.0001) .

Multicentre implications

There were no significant differences regarding the distribution of age, gender and strata, as well as the risk measures of CROM (ANOVA, p>0.19), VAS neck/headache (ANOVA, p>0.20) and non-painful symptoms (ANOVA, p>0.58). However, there were differences in intertester variability for total palpation (ANOVA, p<0.001) and pressure algometry (p<0.01).

Embedded in treatment study

The present study was embedded in a treatment study in which patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk treatment groups (figure 1). A stratified analysis of the seven strata, split into low-risk and high-risk groups, yielded no difference on 1-year work disability based on their given treatment (K-W p>0.15 for patients in the high-risk group; p>0.91 for low-risk patients).

Discussion

This study shows that an early classification of patients into risk strata based on biological and certain psychosocial functions predicts non-recovery. In order to group patients into seven different strata, we used a scaling system resulting from observational findings from a former study. This system included four predefined categories: neck pain intensity, headache intensity, the number of non-painful symptoms and reduced neck mobility. The strata set in the present study were applied in clinical procedures undertaken at a time point where chronic symptoms could not have developed, that is, <median 5 days after injury. The scoring on neck mobility and non-painful symptoms was based on previous observations where a control group was included.19 The summation score was arbitrarily determined, and it may be argued that if another scoring had been used, other findings might have been ascertained. Nevertheless, the scoring was derived from the findings from a prospective observational study of acute whiplash patients (WAD I–III) with an ankle-injured control group in which active neck mobility was the most significant predictor for 1-year work disability.18 Neck pain/headache intensity, as well as a high number of non-painful complaints, was also predictive, though to a lesser extent,18 similar to the present findings (see ROC curves in online supplementary figure S1 A–D). In the present work and in our previous studies,18 we used return-to-work and number of days parameters with sick leave of 1 year as indicators of 1-year work disability. The use of sick leave as a parameter of non-recovery has been discussed previously.18 It may be argued that sick leave is not a direct measure of non-recovery. But as for subjective symptoms such as pain, it is crucial to select robust and directly quantifiable factors in order to reduce the risk of investigator bias. Moreover, the fact that all measures concluding the risk assessment score were completed shortly after injury means that patients were in all probability prevented from changing their habitual, preinjury health belief, which could have been affected by various sources, like the mass media, healthcare persons, family or friends.24 28

Furthermore, patients were not informed or made aware of whether they belonged to a high-risk or a low-risk group, and factors for the risk assessment score were obtained before randomisation. Biological responses like neck strength, duration of neck movement19 and psychophysical-like muscle tenderness by palpation and pressure algometry and the coldpressor pain response,19 as well as stressful parameters like fear avoidance and intrusion parameters and work-related issues, are logically distributed in the risk strata. We did, however, find intertester variability for algometry and palpation, which may need more attention than we offered in this setting (see Methods section), and which has been reported in other studies.29 30 CROM, VAS neck pain/headache and the number of non-painful symptoms did, however, not show unacceptable variability in the current study.

The present risk stratification scheme rests on a selected and limited number of symptoms and signs based on prior observed findings. Legislative and detailed psychosocial factors were not included in the stratification. Such factors might also have an impact, although the chances are that legislative issues hardly affect recovery as early as 5 days after injury. There may be other possible factors that can affect recovery.31 In the present paper, we suggest a way of stratifying whiplash patients in the acute state in order to improve the predictive power of prognosis. Although the risk strata presented here need to be tested as prognostic factors in other cohorts in order to validate our findings, the present study is one of the largest materials in the literature. Moreover, the system has not yet been tested in relation to its possible usefulness in guiding clinical decisions about the choice of treatment. It is a possible downside to risk assessment that healthcare professionals could make premature or hasty decisions when faced with a certain patient who scores high on a prognostic scale like ours. With such scorings, healthcare professionals might unconsciously associate the patient's injury with a prognosis of the chronicity type and act accordingly to some extent. The Quebec Task Force's WAD grading represented a first attempt to better characterise and identify patients at risk for long-term consequences after a whiplash injury. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that the Quebec WAD grading was of little value in predicting long-term sequelae.9 32 More recent prospective papers have stressed the importance of emotional distress, and social factors as risk factors for reduced recovery,33 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),15 33 catastrophising,34 kinesiophobia28 31 35 and stress-response36 are factors associated with the risk of persistent complaints. A trajectory system has been proposed by Sterling et al15 including four groups from no pain/disability to severe pain/disability, in accordance with post-traumatic stress, which needs further validation. It is generally agreed upon that there is a need for studies confirming and validating prognostic models and a need for improved models after acute WAD.37 Other studies have found post-traumatic stress,15 as well as the presence of sensitisation38 and neck pain and headache intensities to be predictive of chronic neck disability 1 year after injury.10 39 These findings are consistent with the present results. Expectations for recovery40 perceived injustice after the accident.41 Reduced active neck mobility has assumed importance in some, but not a majority of, prospective studies.42 It is of interest when the CROM test, on its own, reaches an area under the ROC curve of 0.79 (CI 95 075 to 0.85) (see online supplementary figure S1 B) in this multicentre study in a prediction of 1-year work disability. A critical view on design, taking other risk factors into account, is however also needed for future prediction studies that are highly needed in the whiplash area.37

Conclusion

The risk assessment score is applicable and inexpensive. The early identification of whiplash-exposed persons at risk for chronic pain and work disability is important for planning future treatment in scientific studies.

More research is needed at present, but risk stratification might have a place in the clinic for individual guidance and management of the acute and the subacute whiplash patient. Application of the risk assessment score may be a valuable alternative to the present WAD grading system in predicting work disability and pain and certain psychosocial parameters after neck injury. Furthermore, a similar biopsychosocial risk assessment could be considered in other acute conditions bearing a risk of long-term development of other chronic dysfunctional pain conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Participants were recruited with the help of the staff at the emergency units at hospitals in the four former counties of Viborg, Aarhus, Vejle and Funen during the enrolment period. Statistical consultation was provided from the Department of Statistics, University of Southern Denmark on designing the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: HK, TJ, TB and FB initially conceived the idea of the study; further elaboration of the protocol was made by AK and EQ, and all authors were responsible for the design of the study. Analysis of data was performed by HK, TJ and AK. HK, TJ, FB, TB, EQ and AK contributed to the interpretation of results. HK, TJ, TB, FB and AK were involved in the development of graphs and tables for the manuscript. The main draft of the manuscript was performed by HK and TJ. Critical revisions were made by AK, TB and FB. All writers took part in the successive drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: Financial support was provided by an unrestricted grant from The Danish Insurance Association.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Scientific Committee for The Counties of Vejle and Funen, Project number 20000268, Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Brandsborg B, Dueholm M, Nikolajsen L, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for pain persisting 4 months after hysterectomy. Clin J Pain 2009;25:263–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolajsen L, Brandsborg B, Lucht U, et al. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006;50:495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aasvang EK, Gmaehle E, Hansen JB, et al. Predictive risk factors for persistent postherniotomy pain. Anesthesiology 2010;112:957–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367:1618–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolajsen L, Ilkjaer S, Christensen JH, et al. Pain after amputation. Br J Anaesth 1998;81:486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen BK. Migraine and tension-type headache in a general population: precipitating factors, female hormones, sleep pattern and relation to lifestyle. Pain 1993;53:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galasko CSB, Murray PM, Pitcher M, et al. Neck sprains after road traffic accidents: a modern epidemic. Injury 1993;24:155–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kongsted A, Leboeuf-Yde C. The Nordic back pain subpopulation program: course patterns established through weekly follow-ups in patients treated for low back pain. Chiropr Osteopat 2010;18:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining ‘Whiplash’ and it's management. Spine 1995;20:1S–73S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams M, Williamson E, Gates S, et al. A systematic literature review of physical prognostic factors for the development of Late Whiplash Syndrome. Spine 2007;32:E764–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasch H, Qerama E, Kongsted A, et al. Deep muscle pain, tender points and recovery in acute whiplash patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Pain 2008;140:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasch H, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Pain thresholds and tenderness in neck and head following acute whiplash injury: a prospective study. Cephalalgia 2001;21:189–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterling M. Differential development of sensory hypersensitivity and a measure of spinal cord hyperexcitability following whiplash injury. Pain 2010;150:501–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koelbaek Johansen M, Graven-Nielsen T, Schou-Olesen A, et al. Generalised muscular hyperalgesia in chronic whiplash syndrome. Pain 1999;83:229–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J. Similar factors predict disability and posttraumatic stress disorder trajectories after whiplash injury. Pain 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottrup H, Andersen J, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Psychophysical examination in patients with post-mastectomy pain. Pain 2000;87:275–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aasvang E, Kehlet H. Chronic postoperative pain: the case of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth 2005;95:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasch H, Bach FW, Jensen TS. Handicap after acute whiplash injury: a 1-year prospective study of risk factors. Neurology 2001;56:1637–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasch H, Qerama E, Kongsted A, et al. The risk assessment score in acute whiplash injury predicts outcome and reflects biopsychosocial factors. Spine (PA 1976) 2011;36:S263–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kongsted A, Qerama E, Kasch H, et al. Education of patients after whiplash injury: is oral advice any better than a pamphlet? Spine (PA 1976) 2008;33:E843–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kongsted A, Qerama E, Kasch H, et al. Neck collar, “act-as-usual” or active mobilization for whiplash injury? A randomized parallel-group trial. Spine (PA 1976) 2007;32:618–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasch H, Qerama E, Kongsted A, et al. Clinical assessment of prognostic factors for long-term pain and handicap after whiplash injury: a 1-year prospective study. Eur J Neurol 2008;15:1222–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 1997;72:95–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom med 1979;41:209–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasch H, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Headache, neck pain, and neck mobility after acute whiplash injury: a prospective study. Spine (PA 1976) 2001;26:1246–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunketorp L, Lindh M, Carlsson J, et al. The perception of pain and pain-related cognitions in subacute whiplash-associated disorders: its influence on prolonged disability. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:271–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen K. Quantification of tenderness by palpation and use of pressure algometers. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy New York: Raven Press, 1990:165–81 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendtsen L, Jensen R, Jensen NK, et al. Pressure-controlled palpation: a new technic which increases the reliability of manual palpation. Cephalalgia 1995;15:205–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedler A, Sterling M. Assessing fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with whiplash-associated disorders: a comparison of 2 measures. Clin J Pain 2011;27:502–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kivioja J, Jensen I, Lindgren U. Neither the WAD-classification nor the Quebec Task Force follow-up regimen seems to be important for the outcome after a whiplash injury. A prospective study on 186 consecutive patients. Eur Spine J 2008;17:930–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carstensen TB, Frostholm L, Oernboel E, et al. Post-trauma ratings of pre-collision pain and psychological distress predict poor outcome following acute whiplash trauma: a 12-month follow-up study. Pain 2008;139:248–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivest K, Cote JN, Dumas JP, et al. Relationships between pain thresholds, catastrophizing and gender in acute whiplash injury. Man Ther 2010;15:154–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buitenhuis J, Jaspers JP, Fidler V. Can kinesiophobia predict the duration of neck symptoms in acute whiplash? Clin J Pain 2006;22:272–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kongsted A, Bendix T, Qerama E, et al. Acute stress response and recovery after whiplash injuries. A one-year prospective study Eur J Pain 2008;12:455–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterling M, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, et al. Prognosis following whiplash injury: where to from here? Spine 2011;36:S330–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sterling M, Jull G, Kenardy J. Physical and psychological factors maintain long-term predictive capacity post-whiplash injury. Pain 2006;122:102–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholten-Peeters GGM, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, et al. Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain 2003;104:303–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, et al. Expectations for recovery important in the prognosis of whiplash injuries. PLoS Med 2008;5:e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan MJ, Scott W, Trost Z. Perceived injustice: a risk factor for problematic pain outcomes. Clin J Pain 2012;28:484–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendriks EJM, Scholten-Peeters GGM, van der Windt D, et al. Prognostic factors for poor recovery in acute whiplash patients. Pain 2005;114:408–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.