Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of collaborative care in reducing depression in primary care patients with diabetes or heart disease using practice nurses as case managers.

Design

A two-arm open randomised cluster trial with wait-list control for 6 months. The intervention was followed over 12 months.

Setting

Eleven Australian general practices, five randomly allocated to the intervention and six to the control.

Participants

400 primary care patients (206 intervention, 194 control) with depression and type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease or both.

Intervention

The practice nurse acted as a case manager identifying depression, reviewing pathology results, lifestyle risk factors and patient goals and priorities. Usual care continued in the controls.

Main outcome measure

A five-point reduction in depression scores for patients with moderate-to-severe depression. Secondary outcome was improvements in physiological measures.

Results

Mean depression scores after 6 months of intervention for patients with moderate-to-severe depression decreased by 5.7±1.3 compared with 4.3±1.2 in control, a significant (p=0.012) difference. (The plus–minus is the 95% confidence range.) Intervention practices demonstrated adherence to treatment guidelines and intensification of treatment for depression, where exercise increased by 19%, referrals to exercise programmes by 16%, referrals to mental health workers (MHWs) by 7% and visits to MHWs by 17%. Control-practice exercise did not change, whereas referrals to exercise programmes dropped by 5% and visits to MHWs by 3%. Only referrals to MHW increased by 12%. Intervention improvements were sustained over 12 months, with a significant (p=0.015) decrease in 10-year cardiovascular disease risk from 27.4±3.4% to 24.8±3.8%. A review of patients indicated that the study's safety protocols were followed.

Conclusions

TrueBlue participants showed significantly improved depression and treatment intensification, sustained over 12 months of intervention and reduced 10-year cardiovascular disease risk. Collaborative care using practice nurses appears to be an effective primary care intervention.

Trial registration

ACTRN12609000333213 (Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry).

Keywords: Mental Health, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

To determine the effectiveness of a collaborative care model to reduce depression in primary care patients with diabetes or heart disease.

To determine the effectiveness of using practice nurses as case managers of patients with depression and diabetes, heart disease or both.

Key messages

The TrueBlue model of collaborative care can be introduced within the general practice workforce with practice nurses taking on the role of case manager.

Practice nurses can improve the care of depression in patients with diabetes or heart disease, leading to better outcomes and reduced 10-year cardiovascular disease risk.

The care of patients using the TrueBlue model is closer to ‘best practice’ guidelines, with substantially better levels of adherence to guideline-recommended checks than those occurring in usual care.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The TrueBlue model of collaborative care overcomes many of the difficulties in implementing a guideline for the treatment of comorbid depression.

The study's purpose-designed care plan gives patients and their carers, allied health professionals, specialists and general practitioners ready access to patient details, enabling them to see at a glance where improved clinical care may be needed.

Clinics were able to recover the costs of the collaborative care through Australian Medicare rebates.

The study could only be run in practices that had a practice nurse on staff to carry out the intervention and had access to clinical software capable of generating a disease registry from which patients could be selected to participate in the trial.

Differences between TrueBlue-practice and control-practice outcomes may have been reduced by patients completing the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression questionnaire and reading the project description, and by general practitioners being made aware of individual PHQ-9 results so that they could take action where warranted.

Introduction

Management of diabetes and heart disease has been highlighted as one of the global ‘grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases’1 because the prevalence of these two preventable diseases is increasing.2 Along with depression, they have been identified as health priority areas in many countries. A vicious cycle exists between depression and these chronic diseases, with each being a risk factor for the other.3 Higher mortality has been demonstrated for people with depression and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) or coronary heart disease (CHD) beyond that due to the separate diseases alone.4 For patients with depression and T2DM or CHD or both, there are increased risks of adverse outcomes,5 but this comorbid depression is often missed in primary care.6 Consequently, the identification of depression has now been incorporated into many heart disease guidelines as one of the requirements for optimal management. Meeting these challenges will require an innovative use of the existing general practice workforce, and such a reorientation of resources has been identified as one of the grand challenges.1

Collaborative care is a system that has been shown to be more effective for chronic disease management than standard care.7 It includes a reorientation of the medical workforce through new or adjusted roles for team members, particularly using practice nurses (PNs) as the identified case manager to undertake the care of the patients.8 9 It also includes the use of evidence-based guidelines, systematic screening and monitoring of risk factors, timetabled recall visits, information support for the clinician, enhanced patient self-management, a means of effective communication between all members of the care team and audit information for the practice. Since self-care for diabetes has been found to be suboptimal across a range of self-managed activities, particularly for patients with depression, a collaborative care model may be able to achieve better quality of care through the case manager monitoring patient progress.10 11

Evaluation of a change in the way general practice clinics look after patients requires complex intervention methodology12 beyond single interventions such as the introduction of a guideline with financial incentives.13 This methodology began with a search for potential models of care (step I), and led to adopting the University of Washington's successful IMPACT model of Collaborative Care for depression.14 15 In the exploratory trial (step II), our pilot project16 adapted IMPACT by training PNs as case managers. PNs were trained to screen for depression using a patient self-report measure, the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),17 as part of comprehensive chronic disease management. They were also trained to use a protocol for care management based on the depression scores. The depression screening and management were embedded in routine visits for patients with diabetes or CHD. The pilot demonstrated that it was feasible to detect, monitor and treat depression in routine general practice alongside the usual biophysical measures, and identified moderate-to-severe depression in 34% of participants. The TrueBlue study was a randomised cluster trial (step III) that built on and extended the pilot. It investigated whether a collaborative care model (the intervention) is better than usual care (the control) for the management of patients with depression and T2DM, CHD or both in Australian general practice. It was designed to fit into normal clinic operations, making use of practice nurses and medical software, and was able to be funded by existing Australian Medicare rebates.

Methods/design

Study design

The design and methodology of the study have been described in detail elsewhere.18 The study started in 2009 and was undertaken in two phases. The first phase was a cluster randomised intervention trial in which general practices were randomly allocated to either an intervention group, in which nurse-led collaborative care was undertaken, or to a wait-list control group in which usual care led by the general practitioner (GP) was continued. At 6 months, the TrueBlue training was provided to the control practices. The key aims of the first phase were to determine whether participants with moderate-to-severe depression in the intervention group showed at least a five-point reduction from the baseline depression scores after 6 months of intervention and whether this reduction was significantly better than in the control group. A five-point reduction reflects a clinically relevant change in individuals receiving depression treatment.19 The secondary outcome was to determine whether the intervention also led to improvements in the patients’ physiological measures. The second phase followed the intervention group for an additional 6 months to determine how the collaborative care model affected health outcomes over a 12-month period.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on detecting a 50% reduction in depression score at the 0.05 significance level with 80% power and a two-tailed test. Detecting a 50% reduction is more stringent than detecting a five-point reduction and provided some additional buffering. Using depression scores from an earlier study (a mean of 5.5 and an SD of 6.1),11 the calculation indicated that 237 patients would be required in each group. An intracluster correlation of 0.04 was used (SK Lo, personal communication), with a recruitment target of 50 patients per clinic. (Fifty patients were chosen so that clinics could budget for a nurse's time to carry out the intervention with four patients each week over the 3-month cycle of care.) To allow for difficulties in recruitment, a 50% dropout was used. On the basis of these, the study required 450 patients from nine clinics in the intervention group and the same in the control group.

Practice recruitment

Practices were identified in city and country areas on the basis of having a PN to provide the collaborative care and being able to identify eligible patients, those with CHD or T2DM or both, from their registries; these were invited to participate in the study until the 18 clinics required by the sample-size calculation were recruited. They were allocated by a random number generator to either the intervention or control arm of the study. The unit of randomisation was the clinic. Five practices (three country, two city) in the intervention group and six (two country, four city) in the control group completed the study. One country intervention clinic withdrew while the first-visit data were being collected when its TrueBlue-trained PN left the clinic, but some (n=13) patients from it did complete the study and data were collected from them. The study team was not able to determine why the other clinics withdrew.

Patient selection

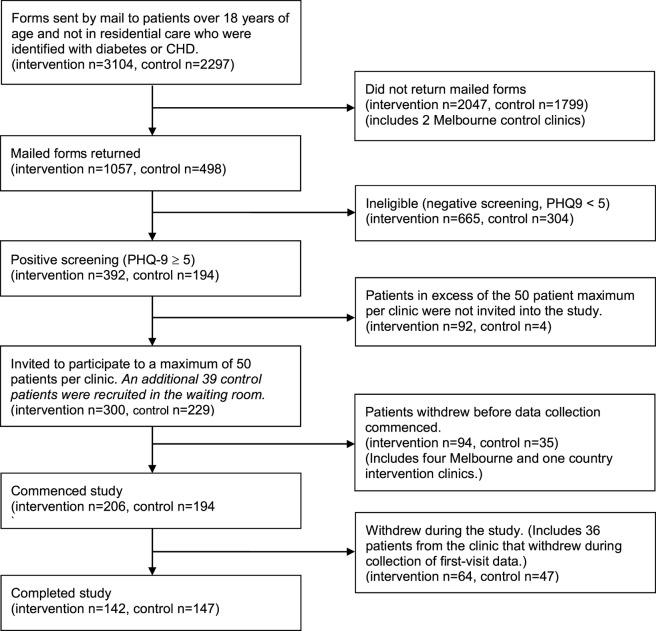

Eligible patients were sent a postal survey that included a consent form which they were asked to complete and return with the enclosed PHQ-9 questionnaire, a self-report measure of depression.17 The PHQ-9 has nine items, each scored from 0 (no problems) to 3 (problems nearly every day). The sum of the scores of the nine items will lie in one of five depression categories: none (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19) and severe (20–27). (While it is known that responses to some of the PHQ-9 items may overlap with diabetes symptoms,20 our pilot demonstrated that nurses and patients preferred using the PHQ-9 because the patient's response to each of its items became the basis for the problem-solving and goal-setting activities that were part of TrueBlue.) Patients with scores of 5 or above, indicating some form of depression, were invited to participate in the study. A maximum of 50 patients per practice were invited. Patients in residential care or under 18 years of age were not eligible. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT diagram of the patient-recruitment process.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the recruitment process.

Patient safety

Participation in the intervention included a series of patient visits to their PN and usual GP every 3 months over a 12-month period. Patients in the control group continued with their ‘usual care’. The control clinics were also provided with the PHQ-9 depression scores to ensure patient safety during the trial. The protocol required that PNs take action if severe depression was recorded in the returned PHQ-9 or if the patient had responded to the suicidal-ideation question (question 9) on the questionnaire. This action was to be taken irrespective of whether the clinic was in the intervention or the control group.

PN training

The PN training included a 2-day workshop to prepare them for their enhanced roles in nurse-led collaborative care. Topics in the workshop included identifying and monitoring depression using the PHQ-9 questionnaire, and quality of life responses using V.2 of the SF36 questionnaire.21 Patient goal setting and problem solving were key components of the training with a particular emphasis on behavioural techniques to achieve improved mental health.22 The training also prepared the PNs for their role as case managers including ensuring that the Diabetes Australia and Australian National Heart Foundation guidelines were being followed and referrals were provided to appropriate services, such as allied health and mental health professionals, through discussion with the GPs.

Data collection

The research team developed a protocol-driven care-plan template from which study data could be extracted automatically and sent to the research team. The template was designed to be a multipurpose document in which the patient's medical history, current medications, allergies, biophysical and psychosocial measures, lifestyle risks, personal goals and referrals were recorded. It was designed to comply with the requirements to claim Australian Medicare rebates for care planning and to provide a checklist for ‘gold-standard’ care. A copy of the care plan was provided to the patient as a written record of their progress.

The care-plan template collected physical measures, including body mass index, waist circumference, weight and blood pressure and the latest pathology results, including lipid profile, glycaemic control (glycosylated haemoglobin, HbA1c) and renal function. Data also included lifestyle risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and level of physical activity, and depression score as measured by the PHQ-9 questionnaire. Referrals to and attendance at exercise programmes and with mental health workers were also recorded, along with the patient's own goals and possible barriers to achieving these goals. The care-plan template was used by the intervention-group clinics to acquire patient data at three monthly intervals over a 12-month period.

In the control group, the only complete dataset recorded using our comprehensive protocol-driven care-plan template was obtained after the 6 months of ‘usual care’ when the TrueBlue training was offered to the control clinics. No baseline or 3-month datasets were acquired since the study was deliberately designed to avoid changing the ‘usual care’ that would have otherwise occurred by introducing our care-plan template. The study was designed in this way to be run pragmatically in the context of the clinics’ normal activities. The only baseline measure obtained was the depression score. On completion of the study, we retrospectively collected all the baseline data that the control clinics routinely recorded in their electronic medical records in order to have data for two time points, baseline and 6 months.

Trueblue collaborative care

As part of the TrueBlue model, patients were scheduled to visit the practice every 3 months for a 45 min nurse consult followed by a 15 min consult with their usual GP, in which stepped care (psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy) was offered if depression scores had not improved or had not dropped below a value of 5. The PN used the care-plan template and obtained current physical measures and reviewed recent pathology results. PNs also reviewed lifestyle risk factors. They readministered the PHQ-9 and worked with the patient to identify possible barriers to achieving their goals and discussed ways to overcome the barriers. This information gathering phase of the consultation was an opportunity to assist the patient with self-management by discussing the available educational resources, such as the library of fact sheets on aspects of self-management of depression, and setting personal goals for review at the next 3-monthly visit.

Statistical analysis

Participants in this study were clustered under clinics by design. It is known that clinics are likely to be different from each other and that ignoring the nested nature of the data may lead to biased estimates of parameter SEs. However, statistical techniques for correcting for the effects of clustering tend to be overly severe and conservative23 when a small number of higher level units (clusters) are used, and therefore we tested whether the clinics were in fact significantly different from each other. Analysis of covariances (ANCOVAs)24 25 were used to adjust for baseline values and to test the significance of changes in depression scores between clinics after 6 months, using STATA V.11.1 for the statistical analyses.

Of the five clinics in the intervention (clinics 4, 5, 13, 15 and 17), only clinics 4 and 17 were significantly different from each other (F(1,76)=9.6, p<0.001). No other comparisons were significant between intervention clinics. Of the six clinics in the control group (clinics 1–3, 6, 16 and 18), only clinics 6 and 18 were significantly different from each other (F(1,78)=14.5, p<0.001). No other comparisons were significant between control clinics. Furthermore, the intracorrelation coefficient of 0.058 for the primary outcome suggests that only 6% of the variance could be attributed to the clinic's level. Given this lack of difference between the clinics in each arm coupled with the sample-size requirements for reliable multilevel modelling,26 we analysed our data at the patient level.

In order to compare the effectiveness of the TrueBlue care model to the usual-care control, ANCOVAs were used to adjust for baseline values and test the significance of changes in continuous variables between the two groups after 6 months. A multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression (STATA's xtmelogit) was used to test the significance of changes in the binary (categorical) variables between the two groups after 6 months, with time and group as the independent variables and with random effects at the patient level. (We used the mixed-effects logistic-regression model since the pairs of observations over time are not independent, ie, observations at 6 months would be expected to be related to the initial baseline observations.) Within each group, changes between the two time points (baseline and 6-month visits) were tested using paired t tests for the continuous variables and matched-case–control McNemar χ2 tests for the binary variables.

The longer-term effects of the intervention were evaluated over the 12-month period using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression (STATA's xtmixed) for the continuous variables and multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression (xtmelogit) for the binary variables. All the 3-monthly data available in the intervention group over the 12 months were used. Note that the study design could not collect such ‘usual care’ data from the control clinics since the data collection protocol was part of the intervention. In addition, TrueBlue training was provided to these clinics at 6 months after which they ceased to be a control.

Patients from the clinics who withdrew before or during collection of first-visit data were excluded from the analyses. (Data for the 13 patients from one of these clinics who did complete the study have been included.) Characteristics from available clinics were compared between early dropouts and participating clinics and addressed in terms of their possible impact on the generalisability of the results. Missing 6-month data were replaced with their baseline values using the ‘no change’ formulation of intention-to-treat by assuming that no change occurred between baseline and 6 months. The underlying assumptions of the statistical tests used were assessed.

Results

Demographics)

A total of 5401 invitations (3104 interventions and 2297 controls; see figure 1) were posted to patients with either T2DM or CHD (or both) identified in the clinics’ registers. Approximately 30% (1057 interventions and 537 controls, including 39 additional patients invited in the waiting room) of the invitations were returned with completed constant forms and PHQ-9 questionnaires. This proportion is typical in studies of this type reported in the literature. Of these, 34% (300 interventions and 229 controls) were eligible (a depression score or 5 or more) and were invited to participate. However, 25% of these (94 interventions and 36 controls) did not start when their clinics withdrew before data collection began.

Of the 206 patients in the intervention who started the study (figure 1), 17% (n=36) were forced to leave when their clinics withdrew the study. A further 14% (n=28) of patients withdrew as the study progressed, with 4% leaving after 6 months, 5% after 9 months and 5% after the full year. Reasons included leaving the area, going into residential care or becoming too ill to continue, but no consistent pattern could be identified. (The exact numbers for each reason are not known.) In the control group, 24% (n=47) of the 194 patients who agreed to participate had forgotten about the study by the time the 6-month review was to be undertaken and did not want to proceed.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients in both the intervention and control groups who started the study. It shows that these characteristics were similar across both groups. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics between the intervention and control at baseline.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the baseline visits. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control at baseline

| Characteristics | Intervention group (n=170) | Control group (n=147) |

|---|---|---|

| Male (%)/female (%) | 51.8%/48.2% | 55.2%/44.8% |

| Age (year) | 68.0±11.7 | 67.6±11.2 |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (%) | 0.0% | 0.7% |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | 37.6% | 47.6% |

| CHD | 45.3% | 35.8% |

| Both | 17.1% | 16.6% |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.4±6.0 (n=170) | 30.8±6.0 (n=103) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 134.1±19.0 (n=169) | 133.5±19.6 (n=112) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.21±0.94 (n=165) | 4.41±1.06 (n=110) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.73±0.88 (n=165) | 1.92±1.37 (n=105) |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 2.22±0.74 (n=159) | 2.37±0.88 (n=89) |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.23±0.36 (n=159) | 1.18±0.33 (n=97) |

| HbA1c (mmol/l) | 7.00±1.21 (n=94) | 7.19±1.42 (n=69) |

| PHQ-9 score | 10.7±4.7 (n=164) | 11.6±5.5 (n=146) |

| PHQ-9 score range at baseline | 5–24 | 5–27 |

CHD, coronary heart disease; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Phase 1: comparison of outcomes between the control and intervention groups after 6 months

Table 2 presents the baseline and 6-month data for markers used to monitor control of chronic disease for both the intervention and control groups. While the 6-month depression scores for all 310 patients (164 interventions and 146 controls) were significantly lower than those at baseline in both the intervention group (10.7±0.7 reducing to 7.1±0.8, t(163)=8.38, p<0.001) and the control group (11.6±0.9 reducing to 9.0±0.9, t(145)=6.01, p<0.001), the ANCOVA, adjusting for the baseline scores, showed that the improvement was significantly better in the intervention group than in the control group (F(1,309)=6.40, p=0.012). (The 95% confidence ranges are indicated by the plus–minus sign.)

Table 2.

TrueBlue outcomes at 6 months in the intervention and control groups

| Intervention |

Control |

Between groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline | 6 months | Within group* | n | Baseline | 6 months | Within group† | ||

| PHQ9 depression score | 164 | 10.7±0.8 | 7.1±0.8 | p<0.001 | 146 | 11.6±0.9 | 9.0±0.9 | p<0.001 | p=0.012 |

| SF36v2 mental-health score‡ | 71 | 37.2±3.4 | 41.1±3.4 | p=0.034 | Not recorded | NS | |||

| SF36v2 physical-health score‡ | 71 | 39.9±2.2 | 42.5±2.6 | p=0.023 | Not recorded | NS | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 162 | 31.3±1.0 | 31.2±1.0 | NS | 103 | 30.8±1.2 | 31.0±1.0 | NS | NS |

| Waist (cm) | 161 | 104.7±2.4 | 105.0±2.4 | NS | 80 | 104.2±4.0 | 105.8±3.2 | NS | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 161 | 134.2±3.0 | 132.4±2.8 | NS | 112 | 133.5±3.8 | 131.2±3.4 | NS | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 158 | 4.21±0.16 | 4.22±0.14 | NS | 109 | 4.41±0.20 | 4.44±0.20 | NS | NS |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 154 | 2.23±0.12 | 2.17±0.14 | NS | 86 | 2.37±0.18 | 2.29±0.20 | NS | NS |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 154 | 1.23±0.06 | 1.29±0.06 | p=0.023 | 93 | 1.17±0.06 | 1.27±0.08 | p=0.011 | NS |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 158 | 1.72±0.14 | 1.66±0.12 | NS | 104 | 1.84±0.22 | 1.75±0.18 | NS | NS |

| HbA1c (%)§ | 89 | 6.97±0.24 | 6.90±0.26 | NS | 67 | 7.22±0.34 | 7.40±0.36 | NS | p=0.049 |

| 10- Year CVD risk¶ | 61 | 26.9±3.2 | 26.1±3.2 | NS | 46 | 26.3±3.6 | 24.7±3.2 | NS | NS |

| Smoking | 162 | 15 (9%) | 13 (8%) | NS | 110 | 13 (12%) | 13 (12%) | NS | NS |

| Alcohol | 104 | 47 (45%) | 51 (49%) | NS | 42 | 27 (64%) | 27 (64%) | NS | NS |

| Exercises 30 min/day, 5 days/week | 162 | 66 (41%) | 97 (60%) | p<0.001 | 75 | 22 (29%) | 22 (29%) | NS | p<0.001 |

| Referred to exercise programme | 162 | 32 (20%) | 58 (36%) | p<0.001 | 111 | 15 (14%) | 10 (9%) | NS | p<0.001 |

| Attends exercise programme | 162 | 12 (7%) | 23 (14%) | p=0.041 | 79 | 12 (15%) | 9 (11%) | NS | NS |

| On antidepressant medication | 162 | 27 (17%) | 34 (21%) | NS | 113 | 31 (27%) | 36 (32%) | NS | p=0.025 |

| Referred to mental health worker | 162 | 47 (29%) | 58 (36%) | p=0.022 | 114 | 10 (9%) | 24 (21%) | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| Attends mental health worker | 162 | 10 (6%) | 37 (23%) | p<0.001 | 109 | 14 (13%) | 11 (10%) | NS | p=0.044 |

The 95% confidence ranges are indicated by the±sign. Note that lower scores indicate improvement for all items except the SF36v2 and HDL results, where higher scores indicate improvement.

Unit of alcohol is 10 g of ethanol.

The values in brackets are the percentages of the total n.

*Significant difference between baseline and 6-month values within the intervention clinics.

†Significant difference between baseline and 6 months within the control clinics.

‡SF36v2 questionnaires were not collected by all clinics.

§HbA1c results were only available for patients with T2DM.

¶CVD risk could only be calculated for patients with T2DM only.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin was measured only for patients with diabetes; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NS, no significant difference; PHQ9, nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire; SF36v2, V.2 of the Short Form 36-Question health survey; T2DM, type 2 diabetes.

Half of the patients had only mild depression at baseline (PHQ-9 scores between 5 and 9). Because the reported score for many of these patients may be due to their diabetes rather than depression,20 the intervention is unlikely to be able to change these scores. This is one reason why Katon et al15 used a score of 10 or more as an inclusion criterion in their study. Consequently, we examined the change to baseline PHQ-9 scores for the 164 patients (81 interventions and 83 controls) with moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 scores of 10 or more) at baseline. These patients showed significant improvement, with the mean depression score in the intervention group dropping by 5.7±1.3, from 14.4±1.1 down to 8.7±1.3 (t(80)=9.00, p<0.001), a clinically significant change.19 The improvement in the intervention group for these patients was significantly better than in the control group (F(1,161)=4.02, p=0.047) where the depression score dropped by 4.3±1.2, from 15.1±1.1 down to 10.8±1.4 (t(82)=6.88, p<0.001).

Except for the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) measurements, there were no significant changes in biophysical measures after 6 months in either group. Smoking rates were low at baseline in the patients with established cardiovascular risk factors. Recording of alcohol was suboptimal, although it was better than in other Australian primary care surveys.27

The intervention group also showed a significantly greater number of patients exercising, referred to and attending an exercise programme, and referred to and attending a mental health worker after 6 months of collaborative care. In the control group, there were no significant changes observed after 6 months, except that referrals to a mental health worker increased significantly (p<0.001) from 9% to 21%, consistent with the action being taken by the nurses as required by the protocol. Neither group showed any significant changes in the number of patients taking antidepressant medication.

Phase 2: chronic disease outcomes over 12 months using TrueBlue collaborative care

Table 3 presents data at baseline and 12 months for the intervention group for markers used to monitor control of existing diabetes and CHD. The improvement in mental health observed after 6 months was maintained at 12 months, with a significant reduction in the mean depression score being maintained (10.7±0.7 to 6.6±0.7, t(163)=9.92, p<0.001) and nearly 70% of patients having lower depression scores than at baseline after 1 year. Patients with moderate–to-severe depression at baseline showed an even greater improvement after 12 months of collaborative care, with the mean depression score dropping by 6.4±1.2, from 14.4±0.8 to 8.0±1.2 (t(80)=10.41, p<0.001). A significant improvement in the mean SF36v2 composite mental-health and physical-health scores, which was observed after 6 months, was also maintained at 12 months.

Table 3 .

TrueBlue outcomes at 12 months within the intervention clinics only

| Intervention |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline | 12 Months | Within group* | |

| PHQ9 depression score | 164 | 10.7±0.7 | 6.6±0.7 | p<0.001 |

| SF36v2 mental-health score† | 70 | 36.0±3.2 | 41.3±2.8 | p<0.001 |

| SF36v2 physical-health score† | 70 | 40.6±2.2 | 44.3±2.8 | p<0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 142 | 31.4±1.0 | 31.1±1.0 | p=0.006 |

| Waist (cm) | 141 | 105.0±2.4 | 105.2±2.6 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 141 | 135.2±3.2 | 130.2±3.0 | p=0.016 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 138 | 4.18±0.16 | 4.28±0.16 | NS |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 135 | 2.19±0.12 | 2.24±0.20 | NS |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 135 | 1.22±0.06 | 1.36±0.08 | p<0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 138 | 1.73±0.16 | 1.63±0.14 | p=0.004 |

| HbA1c (%)‡ | 79 | 7.01±0.26 | 7.04±0.28 | NS |

| 10-Year CVD risk§ | 55 | 27.4±3.4 | 24.9±3.6 | p=0.015 |

| Smoking | 142 | 15 (11%) | 11 (8%) | NS |

| Alcohol | 95 | 45 (47%) | 47 (49%) | NS |

| Exercises 30 min/day, 5 days/week | 142 | 57 (40%) | 83 (58%) | p<0.001 |

| Referred to exercise programme | 142 | 26 (18%) | 53 (37%) | p<0.001 |

| Attends exercise programme | 142 | 10 (7%) | 17 (12%) | NS |

| On antidepressant medication | 142 | 22 (15%) | 33 (23%) | p=0.001 |

| Referred to mental health worker | 142 | 40 (28%) | 59 (42%) | p<0.001 |

| Attends mental health worker | 142 | 8 (6%) | 25 (18%) | p<0.001 |

The 95% confidence ranges are indicated by the±sign. Lower scores indicate improvement for all items except the SF36v2 and HDL results, where higher scores indicate improvement.

The values in brackets are the percentages of the total n.

Unit of alcohol is 10 g of ethanol.

*Significant difference between baseline and 12-month values.

†SF36v2 questionnaires were not collected by all clinics.

‡HbA1c results were only available for patients with T2DM.

§CVD risk could only be calculated for patients with T2DM only.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NS, no significant difference; PHQ9, nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire; SF36v2, V.2 of the Short Form 36-Question health survey; T2DM, type 2 diabetes.

Physiological measures showed a trend, although not significant, to improvement in weight, systolic blood pressure and HDL. Mean baseline lipids and HbA1c were close to guideline targets. The 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk calculated with the Framingham risk equations28 suggests a small but significant (p=0.015) reduction in risk from 27.4% to 24.8% for patients with only T2DM. (The Framingham risk equations cannot be used for those patients who have CHD.)

The most notable changes in lifestyle after 12 months of the intervention were a significant increase in the number of patients who reported taking regular exercise or being referred to an exercise programme. Reported referrals and visits to a mental health worker and numbers taking antidepressant medication were also significantly greater at 12 months.

The TrueBlue protocol also included goal setting so that patients could become more proactive in their own care. An analysis of participant goals revealed that two-thirds of the visits resulted in at least one behavioural activation goal being set and, over the course of the study, 86% of patients identified a behavioural activation goal.

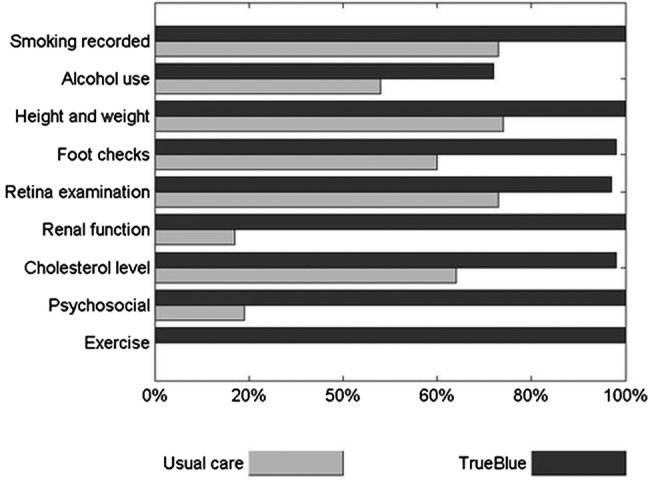

Adherence to guidelines

Figure 2 shows the percentage of TrueBlue patients who had psychosocial and biophysical checks undertaken as recommended by the Australian National Heart Foundation and Diabetes Australia guidelines, with the corresponding percentages for usual care being taken from a study of a large sample of Australian general practices.27

Figure 2.

Recording of checks recommended by the National Heart Foundation and Diabetes Australia guidelines. Data for ‘usual care’ were adapted from reference 27. No usual-care data were available for exercise.

Discussion

Outcomes of phase 1

Depression scores were significantly lower at 6 months for patients in the intervention group compared with those in the control group, and the improvement was clinically significant for patients with moderate-to-severe depression,19 with patients moving one depression category. Patients experienced increased nurse contact time through the nurse consultations. They were provided with information about mental health and their physical health through psychoeducation resources and had their treatment intensified when required. Modalities included behavioural activation, antidepressant medication and referrals to mental health professionals and exercise programmes. Similar improvements in depression scores and stepped-up care were observed in the collaborative care model of Katon et al.15 The reduction in depression scores observed in the control group could be explained, in part, by control practices being provided with each patient's entry-level depression score during the recruitment process as part of the study's safety protocol. Usual care could have been influenced by drawing attention to comorbid depression15 as the protocol required that PNs take action if severe depression was recorded or if the patient had responded to the suicidal-ideation question. Referrals to mental-health workers by the control clinics had increased significantly, consistent with the clinics taking action where warranted. It is also known29 that recruiting interested patients (those who wanted to participate) from interested clinics (those that agreed to join) can affect the representativeness of the study population. GPs with a particular interest in the study may be more likely to participate and manage their patients more effectively, irrespective of whether they are in the control or intervention arm. Consequently, a reduction in depression scores in the control group was expected, but the structured TrueBlue model did produce a significantly better reduction in depression. While the effect size may be small (Cohen's f=0.15), it is important to note that TrueBlue was designed to be implemented easily within general practices, with running costs funded by existing Australian Medicare rebates, and to make better use of their existing resources. These features mean that TrueBlue could be easily applied to patients across general practices at a population level, making the benefits clinically important.

Outcomes of phase 2

The key clinical outcomes over a 12-month period in the intervention group (table 3) were a sustained improvement in mental health, demonstrated by symptom severity score (PHQ-9 total score) and by the patient's function and subjective evaluation of mental health (SF36 mental health composite score) and physical health (SF36 physical health composite score). Regular physical exercise has been shown to be important for reducing depression.30 The self-reported exercise rates showed significant improvement over the 12 months of collaborative care intervention. The biophysical measures reported in table 3 showed modest improvements after 12 months and the Framingham risk equations28 suggest a small but significant reduction in the 10-year CVD risk for the T2DM patients. These improvements were achieved despite the fact that we did not specifically select patients whose physiological parameters exceeded guidelines. Rather, our recruitment process was selected from the practice's disease registry on the basis of only the presence of depression and T2DM or CHD, and consequently, many patients were already being treated to target on measures such as cholesterol and HbA1c, leaving little room for improvement.

Limitations

We were able to run TrueBlue only in practices that used clinical software, which we used to generate a disease registry from which participants could be selected, and had a PN on staff. Clinics that chose to take part in the study may not have been representative of wider general practice. Operational limitations further reduced the number of practices over the duration of the study. Patient response rates to the mail-out (28%) may reflect anxiety over the new model of care where the patient discloses depression and visits the PN first rather than only the GP. Usual care in the control clinics may have been changed by patients completing the PHQ-9 and reading the project description. GPs were made aware of individual PHQ-9 results and took action where warranted. GP awareness of these biophysical and lifestyle risks may be expected to change clinical management. By design, TrueBlue practices needed to incorporate all research activities within the context of their busy clinics, and so only research data that could be extracted automatically were collected. The data dropout resulting from these two factors contributed to the observed small effect size. We were not able to obtain multiple data sets at three monthly intervals over 12 months of ‘usual care’ because the act of inviting patients and measuring depression scores and biophysical measures would in itself change the nature of usual care. In addition, practices would not have been willing to join the study if there was a chance of being randomly allocated to 12 months of being in such a control arm.29

Collaborative care

A recent UK study has shown the difficulties of disseminating a guideline without guidance on how to implement collaborative care. Organisational barriers included GPs finding the PHQ-9 awkward to use, nurses not feeling confident or competent due to lack of training and no guidance on stepped care.13 The TrueBlue model of collaborative care overcame many of these difficulties. Its successful components were:9 31

Use of evidence-based guidelines. The National Heart Foundation and Diabetes Australia Guidelines determined the disease management targets and frequency of monitoring.

Systematic screening and monitoring of risk factors. Patients attended three monthly visits in which a care plan with its checklist was completed. By providing a comprehensive collation of all necessary information, this document made clinical management by the patient's GP easier, quicker and more accurate.

Timetabled recall visits. The date of the next appointment was set during each visit. PHQ-9 was re-administered and, if improvement was insufficient, stepped care was followed by initiating drug therapy or increasing the dose or by referral to a mental-health worker according to the guidelines.

New or adjusted roles for team members. PNs took responsibility for organising and monitoring the outcome of referrals, goals and targets. They used a depression questionnaire (the PHQ-9) to open a discussion with patients about their depression symptoms.

Information support for the clinician. GPs were provided with the care plan by the PNs.

Enhanced patient self-management. Patients received their own copy of the care plan with personalised goals, current measurements, targets and safety advice. A component of each visit was to discuss and update their plan and receive education material on depression.

Identified case manager. PNs became case managers, but the GP remained the key clinician.

Means of effective communication between all members of the care team. The care plan was designed to provide relevant clinical information in a succinct format while still being comprehensible to patients.

Audit information for the practice. Deidentified data were provided automatically through the care plan.

Applicability of TrueBlue

TrueBlue used existing clinical software and improved the focus of the GP consultation by delegating some tasks to the PN. Higher levels of adherence to guideline-recommended checks were also reported for TrueBlue. Patients and their carers, allied health professionals, specialists and GPs gained ready access to patient details provided in TrueBlue's care plan, enabling them to see at a glance where improved clinical care may be needed. The study achieved improved outcomes with the potential for prevention of heart attack and stroke through reduced 10-year CVD risk. The care plan template also allowed the practice to collect high quality audit data without taking up clinical time. While it was not possible to obtain complete financial data from the clinics specifically relating to the TrueBlue visits, the data that are available suggest that clinics did indeed cover their costs in implementing TrueBlue through Australian Medicare rebates. The success of TrueBlue and TeamCare15 demonstrates that collaborative care is feasible in routine general practice in Australia and the USA, and could lead to improved outcomes for patients with depression and other chronic diseases.7 32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, practice nurses, general practitioners and support staff of the participating clinics: Evans Head Medical Centre, Lennox Head Medical Centre, Keen Street Clinic, Tintenbar Medical Centre, Health on Grange, Warradale Medical Centre, Seaton Medical and Specialist Centre, Woodcroft Medical Centre and Southcare Medical Centre. Professors Wayne Katon and Juergen Unützer of the University of Washington were unstinting in their advice on adaptation of the IMPACT model. We would also like to thank Bob Leahy for managing the project, Vince Versace for his statistical advice and Vicki Brown for her assistance during the course of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have full access to the complete study dataset, contributed to the design, implemented the project and cowrote and approved the manuscript. MAJM, MJC, JAD and PR analysed the data. MAJM, PR and KS developed and ran the practice nurse training programme. JAD and PR conceived the TrueBlue model during a visit to the IMPACT team. JAD is the guarantor.

Funding: Funding was provided by beyondblue, the National Depression Initiative in Australia (grant 172), but it had no other involvement in any phase of the study. All researchers were independent of and not influenced by beyondblue.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from Flinders University's Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee. All patients gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset used for the analysis and the computer codes used to produce the results are available from the corresponding author at director@greaterhealth.org.

References

- 1.Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, et al. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature 2007;450:494–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation Preventing chronic disease: a vital investment. Geneva, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, et al. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2006;23:1165–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egede LE, Nietert PJ, Zheng D. Depression and all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality among adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1339–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust 2009;190(7 Suppl):S54–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeling P, Rao BM, Paykel ES, et al. Unrecognised depression in general practice. BMJ 1985;290:1880–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2314–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 1995;273:1026–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickie IB, McGorry PD. Increased access to evidence-based primary mental health care: will the implementation match the rhetoric? Med J Aust 2007;187:100–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2154–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy P, Ford D, Dunbar JA. Improving the quality of diabetes care in general practice. Aust J Rural Health 2010;18:187–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell MJ. Cluster randomized trials in general (family) practice research. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9:81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell C, Dwyer R, Hagan T, et al. Impact of the QOF and the NICE guideline in the diagnosis and management of depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e279–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW, Jr, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care 2001;39:785–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2611–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan MA, Dunbar J, Reddy P. Collaborative care—the role of practice nurses. Aust Fam Physician 2009;38:925–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan M, Dunbar J, Reddy P, et al. The TrueBlue study: is practice nurse-led collaborative care effective in the management of depression for patients with heart disease or diabetes? BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004;42:1194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy P, Philpot B, Ford D, et al. Identification of depression in diabetes: the efficacy of PHQ-9 and HADS-D. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e239–45. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobson KS, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:468–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauermann G, Carroll RJ. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. J Am Stat Assoc 2001;96:1387–96 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senn S. Change from baseline and analysis of covariance revisited. Stat Med 2006;25:4334–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vickers A. The use of percentage change from baseline as an outcome in a controlled trial is statistically inefficient: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2001;1:1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hox JJ. Applied multilevel analysis. 2nd edn Amsterdam: TT-Publikaties, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Q, Harris MF, Jayasinghe UW, et al. Quality of diabetes care and coronary heart disease absolute risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Australian general practice. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:131–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J 1991;121:293–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson S, Delaney BC, Roalfe A, et al. Randomised controlled trials in primary care: case study. BMJ 2000;321:24–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiles NJ, Haase AM, Gallacher J, et al. Physical activity and common mental disorder: results from the Caerphilly study. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:946–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller J, Perkins D, Parker S, et al. Effectiveness of service linkages in primary mental health care: a narrative review part 1. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards DA, Lovell K, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression in UK primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2008;38:279–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.