Abstract

Objective

To examine the excess risk of hospitalisation in patients with incident atrial fibrillation (AF).

Design

A nationwide, retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Denmark.

Participants

Data on all admissions in Denmark from 1997 to 2009 were collected from nationwide registries. After exclusion of subjects previously admitted for AF, data on 4 602 264 subjects and 10 779 945 hospital admissions contributed to the study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Age-stratified and sex-stratified admission rates were calculated for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular admissions. Temporal patterns of readmission, relative risk and duration of frequent types of admission were calculated.

Results

Of 10 779 945 hospital admissions, 729 088(6.8%) were associated with AF. Admissions for cardiovascular reasons after 1, 3 and 6 months occurred for 6.0, 14.3 and 28.4% of AF patients versus 0.2, 0.6 and 1.8 of non-AF patients. Admissions for non-cardiovascular reasons after 1, 3 and 6 months comprised 6.8, 16.1 and 33.3% of AF patients and 1.2, 3.2 and 9.7% of non-AF patients. When stratified for age, AF was associated with similar cardiovascular admission rates across all age groups, while non-cardiovascular admission rates were higher in older patients. Within each age group and for both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular admissions, AF was associated with higher rates of admission. When adjusted for age, sex and time period, patients with AF had a relative risk of 8.6 (95% CI 8.5 to 8.6) for admissions for cardiovascular reasons and 4.0 (95% CI 4.0 to 4.0) for admission for non-cardiovascular reasons.

Conclusions

This study confirms that the burden of AF is considerable and driven by both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular admissions. These findings underscore the importance of using clinical and pharmacological means to reduce the hospital burden of AF in Western healthcare systems.

Keywords: Cardiology, Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

To examine the burden of hospitalisations of atrial fibrillation (AF) in a nationwide setting.

To examine the risk of hospitalisation in patients with AF.

To examine the duration of hospitalisations in patients with AF compared with patients without AF.

Key messages

In all, 6.8% of all hospital admissions in Denmark were associated with AF from 1997–2009 in Denmark.

AF was associated with increased rates of admissions across age groups and for both sexes.

AF was associated with increased length of hospital stay for all diagnoses.

Strengths and limitations of this study

As this is a registry-based study, the limitations of the study include the risk of misclassification as well as the fact that there is no distinction with regard to the severity of AF. The strengths include the large amount of data obtained from nationwide registries.

Introduction

The economic strain of atrial fibrillation (AF) on Western societies is considerable. In fact, the percentage of national health expenditure related to AF is estimated to be 1.3% in Holland and 0.97% in the UK.1 2 The majority of direct costs related to AF are caused by hospitalisations and inhospital procedures.3 4 In the USA, costs directly linked to AF accumulate to 6.65 billion dollars annually, and 73% of these arise from inpatient care with AF as a primary or comorbid diagnosis.5 Thus, the key to lessening the economic strain is to reduce the number of hospitalisations.4 The economic burden of AF is enhanced by the cost of complications, particularly the costs related to stroke.6

AF prevalence increases with age, as shown in the Framingham Heart Study and other studies.7 8 With a growing elderly population in Western societies, the prevalence of AF is increasing; in the USA, the number of patients with AF is expected to double in the next 30 years. As many as 15.9 million people may suffer from AF in the USA by 2050.9–11 The lifetime risk for developing AF for men and women 40 years of age or older is 1 in 4.12 In Denmark, the incidence of AF as a hospital diagnosis more than doubled from 1980 to 1999, and similar trends have been observed in the USA, the UK, Scotland, Australia and Iceland.13–18 The importance of reducing the number of AF hospitalisations is evident.

In clinical trials, hospitalisation is a relevant endpoint in itself, as it provides a direct measure of costs associated with AF; however, it is also a relevant surrogate endpoint for death. The association between cardiovascular-related hospitalisations and death is also highly significant.19 However, to better accommodate care for AF patients, it is essential to define cardiovascular as well as non-cardiovascular hospitalisations and thereby understand the associated comorbidities.19–24

For patients suffering from AF, hospitalisations are associated with a lower quality of life.20 25 Thus, reducing hospitalisations is also desirable on an individual level.

Although several studies have explored the increase in AF-related hospital admissions,11 13 15 18 26–28 no nationwide study has investigated to which degree admissions as a whole are related to AF, or specified the types of diagnoses that are related to AF-associated hospital admissions. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide study to explore the extent to which AF-related hospital admissions and the underlying diagnoses are associated with AF, as well as the likelihood that AF patients are admitted for these diagnoses in comparison with non-AF patients.

Methods

Population

This study is a nationwide registry-based cohort study investigating hospital admissions associated with AF and their influence on later cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular hospitalisations. All data were retrieved from registries on the entire Danish population. Admission data were found in the Danish National Patient Registry, which contains information on all admissions since 1978.29 Our dataset included all admissions from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2009. We excluded patients who had had AF before 1 January 1997. AF diagnosis was defined using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 code I48; for admissions before 1994, it was defined using ICD-8 code 345. As the ICD-10 code (I48) does not distinguish between AF and atrial flutter, patients with atrial flutter were also included. Information about date and primary and contributing causes of death was provided from the Central Population Registry through Statistics Denmark.

All patients with AF before the beginning of the study were excluded; thus, all patients were in the non-AF group at the start of the study. A patient was considered to be in the AF group after the first AF admission. Hospital contacts lasting less than 24 h were excluded because they mostly reflect ambulatory visits. Also, for patients discharged and readmitted on the same date, the admissions were registered as a single admission because the second admission most likely represented transfer to another hospital rather than a true readmission.

Hospital diagnoses

Admissions were classified as cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular admissions or readmissions for AF. Readmission for AF was categorised separately, as many readmissions for AF are, in fact, owing to planned cardioversion or titration of medicine rather than representing a truly new event.19 Cardiovascular admissions were all admissions with an ‘I’-group ICD-10 code, except readmissions for AF that were identified with ICD-10 code I48. All remaining admissions were non-cardiovascular admissions.

Among all hospitalisations from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2009, the most common medical diagnoses for patients with and without AF were identified. The diagnoses constituted the following groups: stroke, heart failure, embolism, ischaemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, syncope, arrhythmia, pneumonia, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperthyroidism, anaemia, hypertension and others, as specified in online supplementary table S4.

Statistical analysis

The study began on 1 January 1997. For univariate construction of Kaplan-Meier curves, AF patients were followed from an index date, which was the date of the first AF admission. Thus, patients with AF were included throughout the study period and, therefore, contributed with different numbers of days. Therefore, the index date for patients without AF was set in the middle of the study period, 1 January 2004. Patients without AF who died before 1 January 2004 were given an alternative index date of 1 January 1997.

For comparisons of hospitalisation rates and multivariable comparisons of risks of hospitalisation, all patients were followed from 1 January 1997 and allocated to the non-AF population until a first hospitalisation for AF.

Technically, time was split at the time of first admission with a diagnosis of AF. Multivariate comparisons of the number of hospitalisations were performed using Poisson regression models adjusted for sex, age and time period. The study period was divided in four epochs to adjust for improvement or changes in care. Age was entered in the model in 5-year intervals. Follow-up ended on 31 December 2009 or at the death of the patient. For the estimation of admission rates and risk of admission, all admissions for all patients were included in the calculations. All statistical analyses and data management were performed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Ethics

Retrospective registry-based studies do not require ethical approval in Denmark. The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the database (no. 2008–41–2685).

Results

Demographics

Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. Data from 4 614 807 subjects were initially included. Of these, data from 12 543 patients were excluded because of a previous diagnosis of AF. The overall median age was 41.3 years (SD 20.2) for individuals without AF and 72.65 years (SD 12.8) for individuals with AF, whereas the mean age in age groups >50–65, 66–75 and >75 years was comparable (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for patients according to the presence or absence of atrial fibrillation

| Overall study population (n=4 602 264) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Non-AF (n=4 447 593) | AF patients (n=154 671) | |

| Female, n (%)* | 2 270 728 (51.06%) | 72 418 (46.82%) |

| Male, n (%)* | 2 176 865 (48.94%) | 82 253 (53.18%) |

| Age ≤50 years | 2 863 317 | 7 417 |

| Age >50–65 years | 856 538 | 28 492 |

| Age >65–75 years | 351 023 | 38 233 |

| Age >75 years | 376 715 | 80 529 |

| Median age (SD) | 41.30 (20.17) | 75.65 (12.76) |

| Median age for age ≤50 (SD) | 31.05 (11–09) | 43.50 (7.23) |

| Median age for age >50–65 | 56.05 (4.31) | 59.68 (4.07) |

| Median age for age >65–75 | 69.71 (2.87) | 70.58 (2.87) |

| Median age for age >75 | 82.05 (5.55) | 82.71 (5.37) |

*p<0.0001.

AF, atrial fibrillation.

From 1997 to 2009, a total of 10 779 945 hospital admissions were identified. Because some patients were admitted more than once during the 13-year period, the number of admissions was higher than the number of patients contributing to the data. A total of 729 088 (6.8%) admissions were related to AF.

Admissions during short-term, medium-term and long-term follow-up

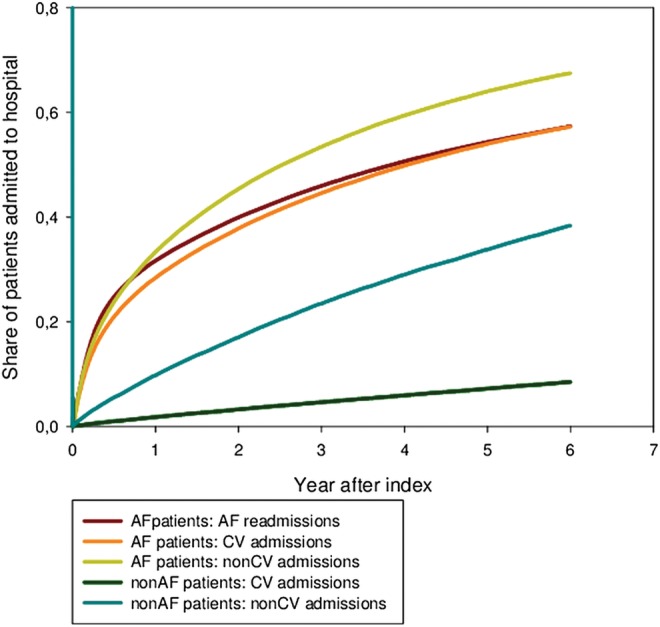

Figure 1 shows the unadjusted accumulated share of patients admitted to the hospital for cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular reasons related to AF, as well as readmissions for AF. Hospitalisation for cardiovascular reasons after 1, 3 and 12 months occurred for 6.0, 14.3 and 28.4% of AF patients versus 0.2, 0.6 and 1.8% of non-AF patients. Non-cardiovascular hospitalisations after 1, 3 and 6 months were registered for 6.8, 16.1 and 33.3% vs 1.2, 3.2 and 9.7% of AF and non-AF patients, respectively. Long-term follow-up revealed that after 6 years, 57.2% of patients with AF were admitted to hospital for cardiovascular reasons, versus 8.5% of patients without AF; the corresponding numbers for non-cardiovascular admissions were 67.5 and 38.4 of AF and non-AF patients, respectively. A total of 57.4% of AF patients were readmitted to the hospital.

Figure 1.

Accumulated share of patients with cardiovascular(CV) or non-cardiovascular (non-CV) admissions or according to atrial fibrillation (AF) or readmissions for AF.

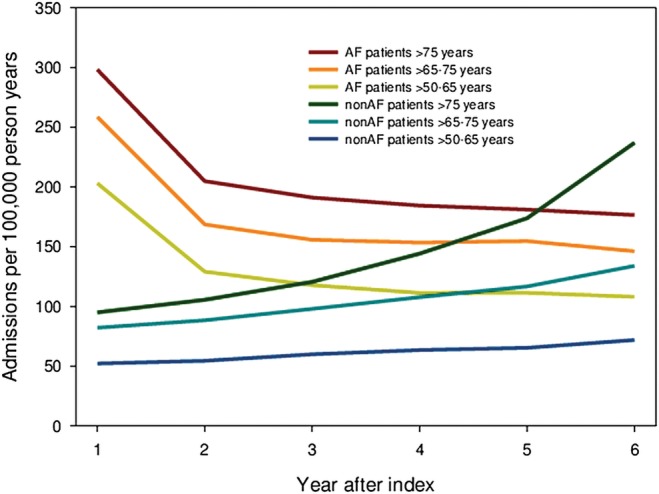

Admission rates were stratified for age and sex. Figure 2 shows the admission rates for cardiovascular admissions and readmissions for AF each year after inclusion for the following age groups: >50–65, >65–75 and >75 years. Patients with AF experienced especially high rates of cardiovascular admission and readmission for AF during the first year; the admission rates declined thereafter. A similar trend was observed in all three age groups. In the first year, the rate was slightly higher for patients aged >50–65 years; from the third year on, the rate was highest for the oldest age group. For patients aged >65–75 years and older than 75 years without AF, the rate of admission increased slightly during the 6-year follow-up; in comparison, the admission rate remained stable during follow-up for non-AF patients aged >50–65 years. Throughout the follow-up period, admission rates for cardiovascular reasons were higher for AF patients than for non-AF patients, regardless of the age group. AF readmissions are only relevant for AF patients, and the rates decreased in a manner similar to cardiovascular admissions (ie, they decreased rapidly from the first to the second year after index; thereafter, they decreased less steeply). Online supplementary figures S4 and S6 show the respective admission rates for men and women; the trends were similar between the two sexes.

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular admissions and atrial fibrillation readmissions for patients with or without atrial fibrillation. Data shown as admissions per 100 000/person-years and stratified for age.

Figure 3 shows the incidence rates for non-cardiovascular admissions for the age groups of patients >50–65, >65–75 and >75 years. For AF patients, the rate was highest during the first year after index and declined throughout the study period. The difference in admission rates was greater between age groups than the difference between age groups for cardiovascular admissions and readmissions for AF. For non-AF patients, admission rates increased for age groups >65–75 and >75 years throughout the study period, but remained stable for patients aged >50–65 years. For both AF and non-AF patients, the oldest age groups had the highest admission rates for all years. However, for non-cardiovascular admissions, the admission rate for non-AF patients in the oldest age group actually exceeded admission rates for AF patients for the youngest, middle and oldest age groups around years 3, 4 and 5, respectively. Likewise, admission rates for non-AF patients aged >65–75 years exceeded admission rates for AF patients older than 75 years around year 4. Online supplementary figures S5 and S7 depict the admission rates for men and women, respectively.

Figure 3.

Non-cardiovascular admissions for patients according to atrial fibrillation. Data shown as admissions per 100 000/person-years and stratified for age.

Relative risk of admission and length of hospital stay

Table 2 shows the sex, age and calendar year-adjusted relative risk (RR) for admissions for patients with AF versus patients without AF for each type of diagnosis: arrhythmia has the highest RR (RR=20.1, 95% CI 19.8 to 20.3, p<0.001); the RR for valvular disease was also high (RR=13.9, 95% CI 13.7 to 14.1, p<0.0001). In addition, thyroid disease (RR=11.5, 95% CI 11.1 to 11.8, p<0.0001) and heart failure (RR=11.0, 95% CI 10.9 to 11.1, p<0.001) were more than 10 times as likely to cause admission in patients with AF as in patients without AF. For all diagnoses, AF patients were more likely to be admitted to hospital than patients without AF. Overall, patients with AF had an RR of admission for cardiovascular reasons of 8.6 (95% CI 8.5 to 8.6 p<0.001) and 4.0 (4.0 to 4.0 p<0.001) for non-cardiovascular reasons.

Table 2.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% CI for admissions for most common diagnoses adjusted for sex, age and year

| RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diagnoses | 8.6 (8.5 to 8.6) |

| Non-cardiovascular diagnoses | 4.0 (4.0 to 4.0) |

| Arrhythmia | 20.1(19.8 to 20.3) |

| Valvular heart disease | 13.9 (13.7 to 14.1 |

| Thyroid disease | 11.5 (11.1 to 11.8) |

| Stroke | 4.2 (4.1 to 4.2) |

| Heart failure | 11.0 (10.9 to 11.1) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 6.8 (6.8 to 6.8) |

| Diabetes | 5.7 (5.7 to 5.8) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5.2 (5.2 to 5.3) |

| Hypertension | 5.0 (5.0 to 5.1) |

| Embolus | 5.0 (4.8 to 5.2) |

| Syncope | 4.3 (4.2 to 4.4) |

| Pneumonia | 4.1 (4.1 to 4.1) |

| Anaemia | 3.8 (3.7 to 3.8) |

| Other | 3.2 (3.2 to 3.2) |

The term arrhythmia refers to arrhythmias other than atrial fibrillation (AF). AF patients had higher risks for all diagnoses. For all RR, p<0.0001.

Lengths of hospital stay (unadjusted) for the most common types of diagnoses are shown in table 3. Hospital stays were longer for all diagnoses in patients with AF. The longest mean length of stay was associated with stroke: 10.5 (SD 16.5) days for AF patients versus 9.5 (SD 16.1) for non-AF patients. The second longest mean length of stay for patients with and without AF was for pneumonia: 8.7 (SD 10.1) days for AF patients versus 7.7 (SD 9.6) days for patients without AF. The largest differences in mean length of hospital stay between the AF and non-AF populations were associated with thyroid disease (9 days (SD 9.6) versus 7.65 (SD 13.4) days) and ischaemic heart disease (5.8 (SD 8.8) days versus 4.6 (SD 7.8) days).

Table 3.

Mean length of hospital stay resulting from admissions for most common types of diagnoses, according to the presence or absence of atrial fibrillation

| AF patients | Non-AF patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Stroke | 10.5 (16.5) | 9.5 (16.1) |

| Pneumonia | 8.7 (10.1) | 7.67 (9.6) |

| Embolus | 7.9 (9.6) | 7.7 (13.4) |

| Thyroid disease | 7.6 (10.7) | 6.2 (8.9) |

| Heart failure | 7.1 (9.1) | 7.2 (9.2) |

| Diabetes | 7.1 (9.4) | 6.5 (10.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6.9 (7.9) | 6.6 (8.6) |

| Valvular heart disease | 6.4 (8.5) | 5.9 (7.9) |

| Anaemia | 6.3 (8.4) | 5.6 (8.3) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5.8 (8.8) | 4.6 (7.8) |

| Hypertension | 5.5 (8.4) | 5.3 (9.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5.5 (8.7) | – |

| Other | 4.7 (7.5) | 4.0 (8.7) |

| Arrhythmia | 4.3 (7.1) | 3.8 (5.9) |

| Lipothymia | 3.9 (5.0) | 2.6 (5.6) |

All data are provided in days (SD).

AF, atrial fibrillation.

Discussion

Principal findings

During a 13-year period from 1997 to 2009, 6.8% of all hospital admissions in Denmark were associated with AF. After 6 years of follow-up, we found that a very large number of AF patients were admitted to the hospital for cardiovascular as well as non-cardiovascular reasons compared with non-AF patients. For cardiovascular admissions, the admission rates for both AF and non-AF patients during the 6-year follow-up period were similar between age groups. Age-stratified admission rates differed more for non-cardiovascular admissions.

For all diagnoses and diseases, the RR of admission was higher for AF patients than non-AF patients. Furthermore, admissions for all types of included diagnoses resulted in longer hospital stays for AF patients than for non-AF patients.

Share of hospitalisations associated with AF and temporal trends

Studies from New Zealand and Germany have found that the share of patients admitted to the hospital who had AF was 10.4% and 14.5%, respectively;30 31 these are larger proportions of hospital admissions than we observed. This difference might be explained by the choice of study population or registration, as our data include all admissions, whereas the above studies included only admissions to medical units, where a larger share of AF patients might be expected than in an overall hospital setting. Furthermore, echocardiogram documentation was used in the aforementioned studies, whereas AF diagnosis in our study depended on registration and AF may not be registered, particularly if it was a secondary diagnosis. However, a Danish community-based study showed that 94% of all patients diagnosed with AF were seen and registered in the hospital; this information gives us reason to believe that almost all AF-related hospitalisations were registered.32

On the other hand, a Malaysian study of 1435 acute medical admissions in a multiracial setting found that only 40 patients (2.8%) had AF upon or within 48 h of admission.33 This number is much lower than our data suggest, and it might be explained by the difference in the setting and population.

Friberg et al19 found that 6.79% of AF patients were readmitted to the hospital for cardiovascular reasons (including AF) within 3 months, and 22.48% within 12 months. These accumulated shares are lower than ours but may be explained by the fact that Friberg et al omitted data on readmissions within the first 30 days.

Comorbidities and length of hospital stay

We know that AF multiplies the risk of stroke by a factor of 5. However, even though several studies have found that heart failure and ischaemic heart disease are among the most common comorbidities in AF patients, data are scarce regarding the relative risk of admission for these diagnoses for AF patients.8 16 33–35 We found that the RR of admission was 11.0 (95% CI 10.9 to 11.1, p<0.0001) for heart failure and 6.8 (95% CI 6.8 to 6.8, p<0.0001) for ischaemic heart disease.

Our finding that AF admissions result in longer hospital stays than corresponding non-AF-associated admissions is supported by a US study based on 26 964 discharges from neurological and internal medicine services from 1989 through 1991. Five per cent of patients had AF. For AF patients, the mean length of hospital stay was 9.6 (SD 8.6) days, versus 7.6 (SD 9.2) days for patients without AF.34

This finding was also true for stroke patients in a Swedish study in which AF implied a longer inpatient stay at the index event (20.7 days vs 20.1 days, p<0.01) and in a smaller US study on patients after coronary artery bypass grafting.36 37 Longer hospital stays for AF-related stroke patients can be explained by the fact that strokes are worse in AF patients than in non-AF patients: they are associated with poorer prognosis, increased rate of complications and higher inhospital mortality.38

Interestingly, a study found that the total number of bed days associated with AF increased from 167 000 in 1986 to 242 000 in 1996 in Scotland, even though the mean length of stay in hospital decreased from 6 days (IQR 3–9) to 3 days (IQR 1–7) for men, and from 8 days (IQR 4–14) to 5 days (IQR 2–11) for women. The increase is most obvious after 1990–1991, which may be explained by changes in the threshold for hospitalisation, as several trials were published that demonstrated the efficacy of antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in individuals with AF.16 A recent study supports these findings: the number of bed days associated with AF in Australian hospitals increased by 125% from 1993 to 2007. This finding reflects an even steeper 155% increase in the prevalence of AF hospitalisations and a reduction in the mean length of hospital stay for AF from 4.0 to 3.1 days.39 Although we did not calculate the temporal pattern of length of hospital stay or the total number of bed days, this is a relevant topic for further investigation.

Our study shows that AF admissions are associated with similarly high cardiovascular admission rates across age groups; hence, patients aged >50–65 years hospitalised for AF and AF patients older than 75 years of age are equally burdened by cardiovascular comorbidity. This finding may indicate that patients with early AF onset represent a group of patients with a particularly high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and, therefore, an increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular morbidity.

Non-cardiovascular admission rates varied more between age groups, which means that AF has less of an effect on non-cardiovascular comorbidity with regard to ageing. However, within each age group, AF patients experienced higher rates of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular admissions than non-AF patients. This less pronounced impact of AF on the rate of non-cardiovascular admissions most likely reflects the interplay between AF and risk factors for AF (ie, risk factors for certain non-cardiovascular admissions, such as those related to thyroid disease overlap, whereas other non-cardiovascular admissions, such as orthopaedic surgery, are not associated with increased risk of AF). Furthermore, this finding may also suggest that the clinicians’ threshold for admitting patients is influenced by the complexity of the disease entity and by additional comorbidity, such as AF.

Clinical implications

Our study is nationwide and covers all admissions in a 13-year period ending with the end of 2009. Data are solid and prove that AF admissions are associated with increased rates of subsequent cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular admissions. Furthermore, our study explores which diagnoses are particularly frequent for AF patients, which temporal patterns are pertinent for AF patients versus non-AF patients. The implications of this study are that both non-cardiovascular and particularly cardiovascular admissions add to the economic burden associated with AF. Thus, the healthcare system should organise the care of AF patients in order to reduce the rate of admissions. A recent study of outpatient care shows that nurse-led care leads to better adherence to guidelines, which significantly lowers the rates of cardiovascular admissions and cardiovascular death.40 This finding suggests that, with the current guidelines, there is a potential to reduce admission rates and cardiovascular death if the care of AF patients is reorganised in a manner that ensures better adherence to the guidelines’.

Limitations and strengths

The data of this study depend on accurate registration upon hospital discharge. Although the registration of AF has been validated, some cases of AF may not be registered, particularly in cases in which AF is a subordinate diagnosis and only the primary diagnosis is registered. This study is looking at the data from a 13-year period as a whole. There might have been changes in the threshold for hospitalisation; alternatively, the habit of coding admissions with AF may have changed.

Due to the organisation of data, no distinction could be made between AF as a primary or secondary diagnosis. We were only able to explore the associations between diagnoses, and therefore we could not deduce whether longer hospital stays were caused by AF or, alternatively, whether an underlying illness caused both the longer stays and AF. Neither is it possible to determine whether admissions were elective or emergent. Because the AF population was defined solely by diagnostic code, the severity of illness was likely to vary among patients.

The AF group in this study only counted patients who were diagnosed with AF during an admission that lasted 24 h or longer. This criterion means that patients who have been diagnosed at their general practitioner's office or in an outpatient clinic do not contribute to data or are misclassified (ie, some cases do have AF, but are registered without AF in the hospital setting). This situation could lead to an underestimation of the burden of AF or an incorrect index date, as well as an overestimation of comorbidities and thromboembolic risk, if only the sickest AF patients are registered.41 Also, the study findings can not be extended to AF patients managed in outpatient clinics. The ICD-10 code for AF (I48) does not allow any distinction between AF and atrial flutter. Neither can we distinguish among paroxysmal, permanent or persistent AF.

The economic burden associated with AF does not rely on admissions alone. A shorter life span of patients with AF due to increased mortality related to heart failure, dementia and stroke will shorten the pension period and thus reduce expenses related to AF patients. Thus, more aspects need to be considered when analysing the economic burden of AF.

The strengths of the study include the large number of patients in the cohort, as well as diversity due to the nationwide setting. Because of the study design, selection bias has been avoided, as well as bias related to sex, income or willingness to participate. Denmark has traditionally high standards in registries, and the validity of several of the diagnoses has been confirmed.29 42

Conclusion

During a 13-year study period from 1997 to 2009, 6.8% of all hospital admissions in Denmark were associated with AF. Cardiovascular admission and AF readmission rates were higher for AF patients of both sexes and across age groups. Among AF patients, admission rates did not vary much across age groups. Non-cardiovascular admission rates were also higher for AF patients in all age groups with the exception of non-AF patients younger than 75 years of age, who had a higher admission rate than AF patients after year 5 postindex.

In 6 years, 57.2% of all AF patients (vs 8.5% of patients without AF) had been admitted to hospital for a cardiovascular reason. In addition, 67.5% of AF patients (vs 38.4% of patients without AF) were admitted to the hospital within 6 years for non-cardiovascular reasons. Also, admissions for all types of diagnoses resulted in longer hospital stays for AF patients than non-AF patients. As we know that the prevalence of AF is increasing, our finding underscores the importance of using clinical and pharmacological means to reduce the hospital burden of AF in Western healthcare systems.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CTP and CC conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. CTP, CC and GG were responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. JO and MLH provided input into the data analysis and interpretation. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by CC, and was then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by research grants from the Sanofi-Aventis group. The study sponsor had no influence on the design of the study, analysis of data, interpretation of results or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Appendix, statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author at christinebenn@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Heemstra HE, Nieuwlaat R, Meijboom M, et al. The burden of atrial fibrillation in the Netherlands. Neth Heart J 2011;19:373–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart S, Murphy NF, Walker A, et al. Cost of an emerging epidemic: an economic analysis of atrial fibrillation in the UK. Heart 2004;90:286–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringborg A, Nieuwlaat R, Lindgren P, et al. Costs of atrial fibrillation in five European countries: results from the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Europace 2008;10:403–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride D, Mattenklotz AM, Willich SN, et al. The costs of care in atrial fibrillation and the effect of treatment modalities in Germany. Value Health 2009;12:293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, et al. Assessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health 2006;9:348–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ericson L, Bergfeldt L, Bjorholt I. Atrial fibrillation: the cost of illness in Sweden. Eur J Health Econ 2011;12:479–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98:946–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlemagne A, Blacher J, Cohen A, et al. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in France: extrapolation of international epidemiological data to France and analysis of French hospitalization data. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2011;104:115–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rich MW. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2009;25:3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valderrama AL, Dunbar SB, Mensah GA. Atrial fibrillation: public health implications. Am J Prev Med 2005;29:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation 2006;114:119–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;110:1042–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frost L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L, et al. Trends in incidence and mortality in the hospital diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or flutter in Denmark, 1980–1999. Int J Cardiol 2005;103:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wattigney WA, Mensah GA, Croft JB. Increasing trends in hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 1985 through 1999: implications for primary prevention. Circulation 2003; 108:711–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefansdottir H, Aspelund T, Gudnason V, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Iceland and future projections. Europace 2011;13:1110–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, MacLeod MM, et al. Trends in hospital activity, morbidity and case fatality related to atrial fibrillation in Scotland, 1986–-1996. Eur Heart J 2001;22:693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong CX, Brooks AG, Leong DP, et al. The increasing burden of atrial fibrillation compared with heart failure and myocardial infarction: a 15-year study of all hospitalizations in Australia. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:739–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald AJ, Pelletier AJ, Ellinor PT, et al. Increasing US emergency department visit rates and subsequent hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation from 1993 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friberg L, Rosenqvist M. Cardiovascular hospitalization as a surrogate endpoint for mortality in studies of atrial fibrillation: report from the Stockholm Cohort Study of Atrial Fibrillation. Europace 2011;13:626–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Heuzey JY. Hospitalization: a relevant endpoint in atrial fibrillation management? Europace 2011;13:1061–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruskin JN, Singh JP. Atrial fibrillation endpoints: hospitalization. Heart Rhythm 2004;1:B31–4; discussion B4–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the atrial fibrillation follow-Up Investigation of rhythm management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation 2004;109:1509–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyse DG. Are there alternatives to mortality as an endpoint in clinical trials of atrial fibrillation? Heart Rhythm 2004;1:B41–4; discussion B4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyse DG, Slee A, Epstein AE, et al. Alternative endpoints for mortality in studies of patients with atrial fibrillation: the AFFIRM study experience. Heart Rhythm 2004;1:531–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorian P, Guerra PG, Kerr CR, et al. Validation of a new simple scale to measure symptoms in atrial fibrillation: the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Severity in Atrial Fibrillation scale. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009;2:218–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friberg J, Buch P, Scharling H, et al. Rising rates of hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation. Epidemiology 2003;14:666–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA 2001;285:2370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:e2–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jorgensen J, et al. The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 1999;46:263–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart FM, Singh Y, Persson S, et al. Atrial fibrillation: prevalence and management in an acute general medical unit. Aust N Z J Med 1999;29:51–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troster S, Schuster HP, Bodmann KF. Atrial fibrillation in patients of a medical clinic–a marker for multi-morbidity and unfavorable prognosis. Med Klin (Munich) 1991;86:338–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukamal KJ, Tolstrup JS, Friberg J, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of atrial fibrillation in men and women: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation 2005;112:1736–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freestone B, Rajaratnam R, Hussain N, et al. Admissions with atrial fibrillation in a multiracial population in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int J Cardiol 2003;91:233–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali AS, Fenn NM, Zarowitz BJ, et al. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized in a large hospital. Panminerva Med 1993;35:209–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lip GY, Tean KN, Dunn FG. Treatment of atrial fibrillation in a district general hospital. Br Heart J 1994;71:92–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghatnekar O, Glader EL. The effect of atrial fibrillation on stroke-related inpatient costs in Sweden: a 3-year analysis of registry incidence data from 2001. Value Health 2008;11:862–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hravnak M, Hoffman LA, Saul MI, et al. Resource utilization related to atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Crit Care 2002;11:228–38 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek-Bregel M, et al. Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian Stroke registry. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1734–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong TY, Larsen EK, Klein R, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors for retinal vein occlusion and arteriolar emboli: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities & Cardiovascular Health studies. Ophthalmology 2005;112:540–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendriks JM, De Wit R, Crijns HJ, et al. Nurse-led care vs. usual care for patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized trial of integrated chronic care vs. routine clinical care in ambulatory patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2692–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandhu RK, Bakal JA, Ezekowitz JA, et al. The epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in adults depends on locale of diagnosis. Am Heart J 2011;161:986.e1–92e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nickelsen TN. Data validity and coverage in the Danish National Health Registry. A literature review. Ugeskr Laeger 2001;164:33–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.